Abstract

Small direct current (DC) electric fields (EFs) guide neurite growth and migration of rodent neural stem cells (NSCs). However, this could be species dependent. Therefore, it is critical to investigate how human NSCs (hNSCs) respond to EF before any possible clinical attempt. Aiming to characterize the EF-stimulated and guided migration of hNSCs, we derived hNSCs from a well-established human embryonic stem cell line H9. Small applied DC EFs, as low as 16 mV/mm, induced significant directional migration toward the cathode. Reversal of the field polarity reversed migration of hNSCs. The galvanotactic/electrotactic response was both time and voltage dependent. The migration directedness and distance to the cathode increased with the increase of field strength. (Rho-kinase) inhibitor Y27632 is used to enhance viability of stem cells and has previously been reported to inhibit EF-guided directional migration in induced pluripotent stem cells and neurons. However, its presence did not significantly affect the directionality of hNSC migration in an EF. Cytokine receptor [C-X-C chemokine receptor type 4 (CXCR4)] is important for chemotaxis of NSCs in the brain. The blockage of CXCR4 did not affect the electrotaxis of hNSCs. We conclude that hNSCs respond to a small EF by directional migration. Applied EFs could potentially be further exploited to guide hNSCs to injured sites in the central nervous system to improve the outcome of various diseases.

Keywords: Human neural stem cells, Directional cell migration, Electric field, Electrotaxis, Rho-kinase, C-X-C chemokine receptor type 4

Introduction

Stem cells must migrate directionally to diseased or damaged tissues to repair and to regenerate. Limited understanding exists for the mechanisms guiding the migration of transplanted/endogenous neural stem cells (NSCs). When NSCs were transplanted into the rat adult hippocampus, they incorporated into the upper blade [1, 2]. Many signaling molecules have been suggested to guide the migration [3-5]. Damaged brain tissue may signal to recruit transplanted embryonic stem cells (ESCs) to damaged regions, even from the left caudal to the right caudal and left frontal [6]. Some types of damage may need focal delivery of replacement cells, while more widespread damage or damage of less-accessible parts of the brain may require long-range dispersal of NSCs. Unfortunately, very few NSCs survive if directly transplanted to the site of damage [3]. Therefore, it is more plausible to transplant NSCs to the region adjacent to the damage and then induce them to migrate to the damage. Endogenous NSCs may be recruited to the damaged brain areas, but only small portion of the newly produced NSCs are able to do so [7-9].

No clinically effective technique is currently available to guide migration of human NSCs (hNSCs). Guiding migration of hNSCs has direct clinical relevance. NSCs for clinical use must be human. Using hNSCs minimizes tumorigenesis which may be a drawback of using human ESCs (hESCs) [10], and hNSCs have the advantage of ample supply, better survival, and proliferation over terminally differentiated neurons. Significant beneficial effects of transplanting hNSCs have been demonstrated in animal models of stroke [11-13], Parkinson’s disease [14, 15], spinal cord injury [16-19], traumatic brain injury [20, 21], and brain tumor (as an effective delivery system) [22, 23].

Direct current (DC) electric field (EF) is an effective cue to guide neurite growth and migration of neurons and other types of cells [24-30]. Rodent NSCs migrate directionally in an EF [26, 27, 30]. Unfortunately, how hNSCs would respond to an EF cannot be simply deduced from previous publications, because the guidance effect of EFs for cell migration and neurite growth has significant interspecies difference and is cell type dependent. For example, neurites from Xenopus neurons grow remarkably well toward the cathode, those from rat neurons grow perpendicular in an EF, and neurons from zebra fish do not respond to an EF at all [24, 31-33]. Our own investigation using human induced pluripotent stem cells (hiPSCs) and hESCs showed completely different electrotaxis. hiPSCs migrated to the anode, while hESCs migrate to the cathode [34]. Those findings from rodents and from different human stem cells cannot be simply transferred to human cells and to hNSCs derived from H9 ESCs.

Therefore, it is important to test whether hNSCs migrate directionally in an EF. In an effort to develop practical strategies to guide migration of more differentiated cells, we derived hNSCs from a well-characterized hESC line H9 and determined the response to applied EFs. Human NSCs are a cell type of clinical potential for use in brain trauma, stroke, and neurodegenerative diseases. Their responses are thus clinically relevant and form an initial valuable and necessary step before further evaluation in vivo.

Materials and Methods

Derivation of NSCs from H9 ESCs

The multipotency of the derived hNSCs was confirmed by the differentiation into neurons and astrocytes. For neuron differentiation, hNSCs were cultured in neurobasal medium supplemented with B27, brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), ascorbic acid, glial cell-derived neurotrophic factor (GDNF), and cyclic-Adenosine monophosphate (AMP). For astrocyte differentiation, hNSCs were cultured in neurobasal medium supplemented with 1% B27, 1% N-2 supplement, 1 mM l-glutamine, and 1% non-essential amino acid (NEAA). NSC population was expanded in neural induction medium plus 0.1% B27 and 10 ng/ml epidermal growth factor (EGF) on poly-l-ornithine/laminin-coated dishes.

Electrotaxis Experiments

Details were previously reported [35-37]. Cells were seeded in an electrotactic chamber coated with laminin, in CO2-independent medium (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, http://www.invitrogen.com/) plus 1 mM l-glutamine for 0.5–2 hours before the electrotaxis study. Cell migration was recorded using time-lapse digital video-microscopy.

Drug Treatment

Cells were pretreated with either Y27632, a Rho-kinase (ROCK) inhibitor (0, 10, 25 μM), or C-X-C chemokine receptor type 4 (CXCR4) antagonist AMD3100 (0, 5, 25 μg/ml; from Sigma, St. Louis, MO, http://www.sigma.com) for 0.5 hour in a CO2 incubator before the treatment of electrotaxis experiment.

Electrotaxis Analysis

We use the following parameters [28, 34, 37]: (a) directedness = cosine (θ), where θ is the angle between the EF vector and a straight line connecting the start and end position of a cell. A cell moving directly along the field lines toward the cathode (to the right) would have a directedness of +1. A value close to 0 represents random migration. The cosine (θ) will range from −1 to +1, and an average of cosine (θ) yields the directedness value for a population of cells, giving an objective quantification of the direction of cell migration. (b) Track speed (μm/hour): accumulated migrated distance in 1 hour. (c) Displacement speed (μm/hour): the straight line distance from the starting point to the final position of cell in 1 hour. (d) X-axis distance (μm): the distance which is projected on the X-axis (parallel to the EF direction) from the starting point to the final position of cell’s migration.

Cells Markers and Staining

Cells were labeled with rabbit anti-human Sox1 (1:500, Millipore, Billerica, MA, http://www.millipore.com [AB15766]); mouse anti-human Nestin (1:500, R&D, Minneapolis, MN, http://www.rndsystems.com/ [MAB1259]); rabbit anti-human glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) (1:1000, Millipore, Billerica, MA, http://www.millipore.com [AB5804]); rabbit anti-TuJ1 (1:500, Abcam, San Francisco, CA, http://www.abcam.com/ [ab24629]); or rabbit anti-human CXCR4 (1:200, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, http://www.thermofisher.com). Polyclonal secondary antibodies (Alexa Fluor 488 and 594 nm, respectively; Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, http://www.invitrogen.com/) were applied for 1 hour. Cells were mounted with VECTASHIELD mounting medium with 4′6-diaminino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) (Vector laboratories Inc., Burlingame, CA, http://www.vectorlabs.com).

Statistics

Data are expressed as mean ± SEM. Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS software with unpaired, two-tailed Student’s t-test (time- and strength-dependent electrotaxis experiment), or analysis of variance (ANOVA) (Y27632, AMD3100 experiments). p was set at .05 for rejecting null hypotheses.

Results and Discussion

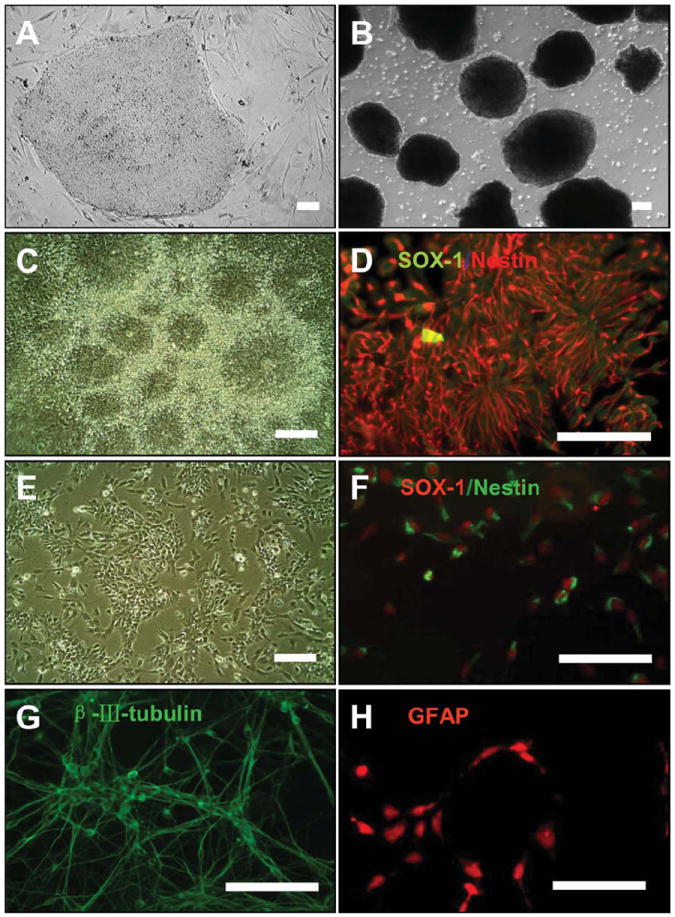

To confirm NSC features of the derived cells, we showed differentiation sequence of H9 ESCs, embryoid body formation, and rosette isolation as previously reported [38]. Immunofluorescence staining showed that columnar cells inside rosettes were positive for neuroepithelial markers, Sox-1 and Nestin. The derived NSCs continued to express those markers. After weeks of directed differentiation, NSCs gave rise to β-III-tubulin-positive neurons and GFAP-positive astrocytes (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Characterization of neural stem cells (NSCs) derived from human embryonic stem cells (hESCs). (A): hESCs (line H9) were cultured on feeder cells. (B): Embryoid bodies were formed in suspension culture. (C): Numerous clusters of columnar cells formed rosettes, after attachment of the embryoid bodies for 1 week. (D): Rosettes were positively labeled with anti-SOX-1 and Nestin antibodies. (E): The isolated rosettes were dissociated into single human NSCs after treatment with accutase. NSCs were cultured as monolayer adherent cells. (F): Immunofluorescence analysis showed that NSCs derived were positive for the neuroepithelial markers, Sox-1 and Nestin. (G): NSCs can be induced to differentiate into β-III-tubulin-positive neurons. (H): NSCs can be induced to differentiate into GFAP-positive astrocytes. Scale bar = 100 μm. Abbreviations: GFAP, glial fibrillary acidic protein; SOX-1, sex determining region Y-box 1.

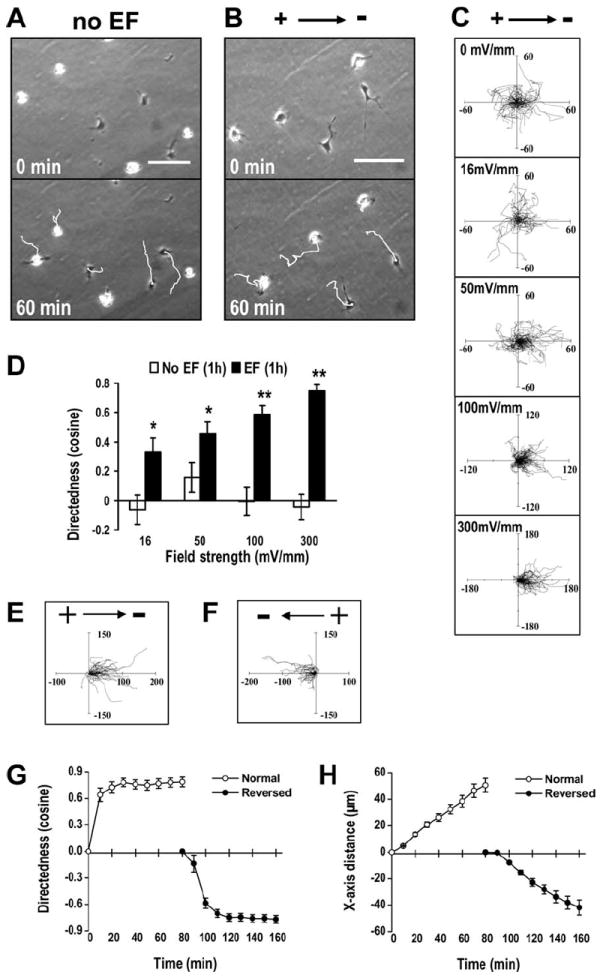

We first determined the response of hNSCs to an EF. Different types of cells, or even the same type of cells from different species, responded remarkably differently to EFs. Robinson and Cormie [39] made a detailed comparison of the responses of different neurons to EFs. One striking difference is that neurites from Xenopus neurons showed directional growth in a very small EF of approximately 8 mV/mm, while neurites from Zebrafish neurons completely ignored the presence of an EF as high as 100 mV/mm, although the growth of neurites was the same [31, 32, 39, 40]. However, neurons from rodents did not respond to applied EFs, or the neurites were orientated perpendicular to the field direction, neither toward the cathode nor the anode [33, 39]. Neuron-like cells differentiated from PC12 cells orientated the neurites toward the anode [41]. Studies suggested that rodent neural stem/progenitor cells migrate to the cathode in an EF [26, 27, 30]. To develop techniques to guide hNSCs exploiting electrical signal to facilitate stem cell therapy, it is therefore important to determine how NSCs of human origin respond to EFs. In an EF, hNSCs migrated directionally to the cathode. Reversal of the field polarity reversed the migration direction (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

An applied direct current (DC) EF-directed migration of human neural stem cells (hNSCs) toward the cathode. (A): hNSCs migrated in random direction when cultured without an EF. The white lines represent tracks of cell migration with the cell positioned at the end of migration at 1 hour. See Supporting Information Video 1. (B): hNSCs showed robust cathodal migration in an EF (300 mV/mm, for 1 hour). See Supporting Information Video 2. (C): Migration trajectories of hNSCs for 1 hour in EFs with the starting point set at the origin. The unit of the axes is in microns. (D): Directedness values of hNSCs in an EF of different field strength at 1 hour. The average cosine increased with field strength. (E, F): Reversed migrations of the same hNSCs followed the reversal of the field polarity. The tracks of cell migration before (E) and after (F) the field polarity was reversed. The unit of the axes is in microns. See also Supporting Information Video 3. (G, H): Reversal of migration direction indicated by the directedness value (G) and X-axis distance (H) of hNSCs migration in an EF before and after polarity reversal. Data were analyzed based on the setting of 0-minute as the start position for the first 80 minutes and 80-minute as the start position for the EF reversed 80 minutes. EF = 250 mV/mm. Scale bar = 100 μm. *, p < .05; **, p < .01 when compared to that of cells cultured in control conditions without an EF. Abbreviations: EF, electric field.

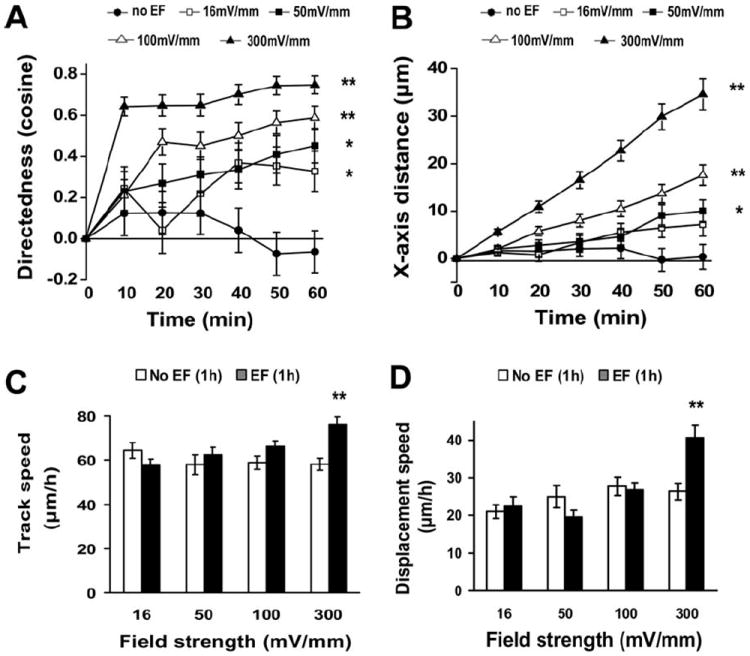

To determine the threshold voltage for EF-directed migration, we subjected the cells to EFs of different strength. The electrotaxis of hNSCs is time and voltage dependent with a threshold of 16 mV/mm or below. Cells showed gradually increased cathodal migration with higher field strength (Figs. 2C, 2D, 3A, 3B). The directedness value increased with EF strength. Additionally, an EF of 300 mV/mm significantly increased cell track speed and displacement speed (Fig. 3C, 3D).

Figure 3.

Voltage dependence and time dependence of the electrotaxis of human neural stem cells (hNSCs). (A): Directedness values (average cosine) represented cumulative directional translocation measured at 10-minute intervals for 1 hour at the four field strengths. (B): X-axis distance toward the cathode was measured at 10-minute intervals for1 hour. (C, D): The track speed and displacement speed of hNSCs for 1 hour. *, p < .05; **, p < .01 when compared to that in no EF at 1 hour. Abbreviations: EF, electric field.

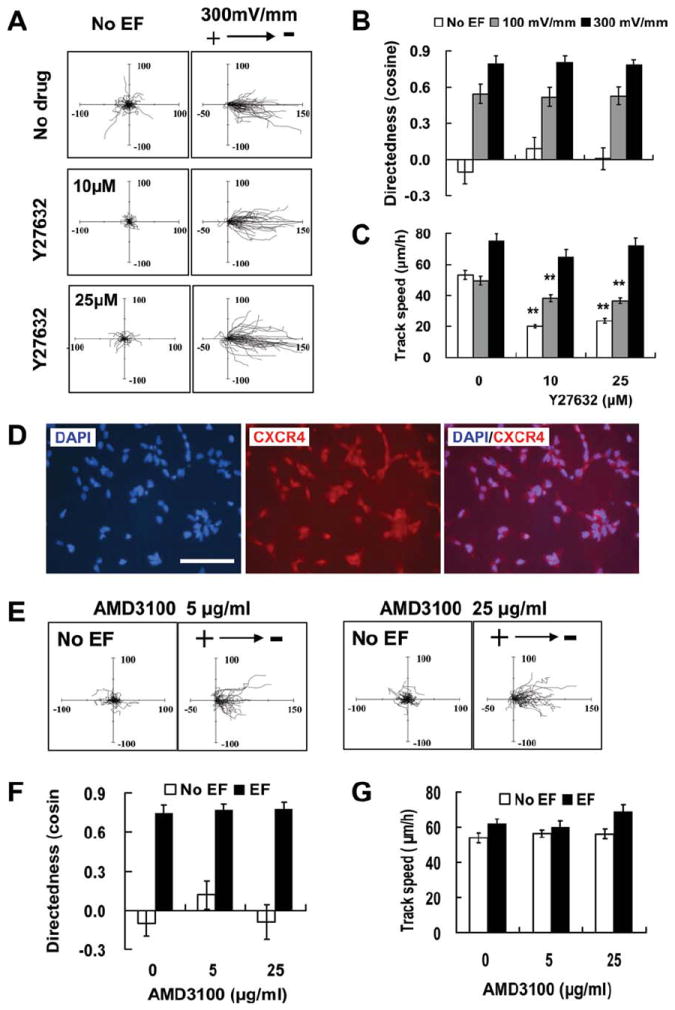

We next examined the effects of Y27632 on EF-guided migration of hNSCs. The compound Y27632 is used in stem cell transplantation and passaging to promote stem cell survival [42]. Y27632 inhibits the Rho A effectors ROCK 1 and 2. Y27632 treatment significantly decreased the track speed when no EF or low EF stimulated, while did not affect the directional migration of hNSCs in an EF (Fig. 4A–4C). ROCK inhibition enhances post-thaw viability of human mesenchymal stem cells (hMSCs) and hESCs [43, 44] and helps survival of transplanted ESC-derived NSCs [42]. It may also regulate neural differentiation [45, 46]. Inhibition of ROCK using Y27632 significantly affected electrotaxis of human iPSCs and rat hippocampus neurons [28, 34, 47]. The directedness value of EF-directed migration of hNSCs, however, was not sensitive to the Y27632 treatment. We finally tested whether the well-studied chemotaxis pathway through CXCR4 is involved in the electrotaxis of hNSCs. CXCR4 is the primary receptor for stromal derived factor-1α (chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand 12 (CXCL12) or SDF-1α), a potent chemokine for stem cell migration. CXCR4 is a key molecule in chemotaxis of many types of stem cells and regulates migration of NSCs derived from ESCs [5, 48]. Evidence suggests that migration of NSCs toward a tumor bed or to the ischemic sites in the brain is also regulated by CXCR4 [49, 50]. CXCR4 is positively labeled in the derived hNSCs (Fig. 4D). Its antagonist AMD3100 had no significant effect on the directional migration or on the track speed of hNSCs with or without EF exposure (Fig. 4E–4G). These results showed that the guidance effect of DC EFs is different from that of chemotaxis for hNSCs. There is a small possibility that Y27632 and AMD3100 may have off target effects. Further molecular experiments will be needed for elucidating the exact signaling mechanisms.

Figure 4.

Y27632 inhibiting ROCK and AMD3100 blocking CXCR4 did not affect electrotaxis of human neural stem cells (hNSCs). (A): Migration trajectories of hNSCs with the starting point set at the origin. The axes are in microns. (B): Y27632 (10, 25 μM) had no significant effect on directedness value of EF-directed migration. (C): Y27632 treatment decreased the track speed when no EF exposure or at low field strength (100 mV/mm) but had no effect on that of hNSCs at 300 mV/mm. D: hNSCs were positively stained for CXCR4. (E): Migration trajectories of hNSCs after AMD3100 treatment. The axes are in microns. (F): AMD3100 (5, 25 μg/ml) did not inhibit the migration directedness of hNSCs in EF. (G): No significant effect of AMD3100 on the track speed of hNSC migration with or without EF. Scale bar = 100 μm. **, p < .01 when compared to that in no drug treatment. Abbreviations: CXCR4, C-X-C chemokine receptor type 4; DAPI, 4′6-diamindino-2-phenylindole; EF, electric field.

EF has some unique properties and could be a technique that compliments other therapies. Several potential methods to direct migration of transplanted stem cells have been explored, including enhancement on chemotaxis of stem cells through gene manipulation of chemokines and their receptors such as SDF-1/CXCR-4, cytokine pretreatment, and extracellular matrix breaking down [48, 51-55]. For example, induced expression of CXCR4 in MSCs significantly increased homing of the cells to the site of infarcted tissue in the heart [56]. However, biochemical guidance cues may be difficult to manipulate. There are very complicated chemical gradients existing in vivo. Those coexisting directional cues in vivo may not only be a confounding factor but also have less predictable or controllable effects on stem cells to home to injured sites or diseased tissues. Thus, chemical gradients are difficult if not impossible to control in vivo. Compared to these biochemical methods, application of an EF has the advantages of easy control of direction, magnitude, immediate application and withdraws, with no chemical residuals. Application of EFs has flexibility of varying strength, time, direction and space location, almost adjustable at will. An applied EF might act on the complicated chemical gradients in vivo. It is not known whether this interaction may cause even more confounding effects in guidance of hNSCs or may unify the guidance effects. Our in vitro results suggest that the guidance effects of EFs on hNSCs appear to be insensitive to ROCK inhibitor Y27632, which is a widely used agent to help maintain stem cells. The SDF-1/CXCR-4 signaling pathway, which is important for stem cell migration, does not have significant effects on electrotaxis of hNSCs. Further experiments using electric stimulation together with other guidance molecules (BDNF, nerve growth factor, and netrins) and ultimately in vivo experiments will be needed to elucidate interaction between the electrical and biochemical signals. Electric stimulation in combination with other cues (growth factors, cytokines, etc.) is likely to lead to a more effective guidance strategy for hNSCs.

Conclusion

In summary, a small EF (16 mV/mm) is an effective cue to guide migration of hNSCs. The guidance effect is different from undifferentiated iPSCs which appeared to depend on Rho/ROCK signaling and also different from chemotaxis through CXCR4 pathway. Electric stimulation may offer a practical approach to facilitate therapies using hNSCs in brain injury, where guided cell migration and integration are needed.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Lin Cao and other members from the Zhao and Nolta laboratories for assistance. This work was supported by grants from the California Institute of Regenerative Medicine RB1-01417 (to M.Z.) and TR1-01257 (to J.N.). M.Z. is also supported by NIH 1R01EY019101, NSF MCB-0951199, and UC Davis Dermatology Developmental Fund, and in part by the Research to Prevent Blindness, Inc. J.N. is also supported by the NIH (5P30AG010129, 5RC1AG036022-02, and 2P51RR00016949). J.F.F. is supported by NSFC (30901543). J.L. is supported by a fellowship from the Shriners of Northern California.

Footnotes

Author contributions: J.-F. F.: conception and design, collection and assembly of data, data analysis and interpretation, and manuscript writing; J.L.: provision of study material, collection and assembly of data, and data analysis and interpretation; X.-Z. Z.: collection and assembly of data; L.Z.: provision of study material and collection and assembly of data; J.-Y. J.: provision of study material; J.N.: financial support, provision of study material, and final approval of manuscript; M.Z.: conception and design, financial support, provision of study material, data analysis and interpretation, manuscript writing, and final approval of manuscript.

See www.StemCells.com for supporting information available online.

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

M.Z. has research funding/contracted research with CIRM.

References

- 1.Gage FH, Coates PW, Palmer TD, et al. Survival and differentiation of adult neuronal progenitor cells transplanted to the adult brain. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:11879–11883. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.25.11879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cassel JC, Ballough GP, Kelche C, et al. Injections of fluid or septal cell suspension grafts into the dentate gyrus of rats induce granule cell degeneration. Neurosci Lett. 1993;150:89–94. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(93)90115-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kelly S, Bliss TM, Shah AK, et al. Transplanted human fetal neural stem cells survive, migrate, and differentiate in ischemic rat cerebral cortex. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:11839–11844. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0404474101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Imitola J, Raddassi K, Park KI, et al. Directed migration of neural stem cells to sites of CNS injury by the stromal cell-derived factor 1alpha/CXC chemokine receptor 4 pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:18117–18122. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0408258102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hartman NW, Carpentino JE, LaMonica K, et al. CXCL12-mediated guidance of migrating embryonic stem cell-derived neural progenitors transplanted into the hippocampus. PLoS ONE. 2010;5:e15856. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0015856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Srivastava AS, Shenouda S, Mishra R, et al. Transplanted embryonic stem cells successfully survive, proliferate, and migrate to damaged regions of the mouse brain. Stem Cells. 2006;24:1689–1694. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2005-0531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Parent JM, Vexler ZS, Gong C, et al. Rat forebrain neurogenesis and striatal neuron replacement after focal stroke. Ann Neurol. 2002;52:802–813. doi: 10.1002/ana.10393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lindvall O, Kokaia Z, Martinez-Serrano A. Stem cell therapy for human neurodegenerative disorders-how to make it work. Nat Med. 2004;10(suppl):42–50. doi: 10.1038/nm1064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhang RL, Zhang ZG, Zhang L, et al. Proliferation and differentiation of progenitor cells in the cortex and the subventricular zone in the adult rat after focal cerebral ischemia. Neuroscience. 2001;105:33–41. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(01)00117-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shih CC, Forman SJ, Chu P, et al. Human embryonic stem cells are prone to generate primitive, undifferentiated tumors in engrafted human fetal tissues in severe combined immunodeficient mice. Stem Cells Dev. 2007;16:893–902. doi: 10.1089/scd.2007.0070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Darsalia V, Allison SJ, Cusulin C, et al. Cell number and timing of transplantation determine survival of human neural stem cell grafts in stroke-damaged rat brain. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2011;31:235–242. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2010.81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jin K, Mao X, Xie L, et al. Delayed transplantation of human neural precursor cells improves outcome from focal cerebral ischemia in aged rats. Aging Cell. 2010;9:1076–1083. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2010.00638.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jin K, Mao X, Xie L, et al. Transplantation of human neural precursor cells in Matrigel scaffolding improves outcome from focal cerebral ischemia after delayed postischemic treatment in rats. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2010;30:534–544. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2009.219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yasuhara T, Matsukawa N, Hara K, et al. Transplantation of human neural stem cells exerts neuroprotection in a rat model of Parkinson’s disease. J Neurosci. 2006;26:12497–12511. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3719-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Redmond DE, Jr, Bjugstad KB, Teng YD, et al. Behavioral improvement in a primate Parkinson’s model is associated with multiple homeostatic effects of human neural stem cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:12175–12180. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0704091104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Salazar DL, Uchida N, Hamers FP, et al. Human neural stem cells differentiate and promote locomotor recovery in an early chronic spinal cord injury NOD-scid mouse model. PloS ONE. 2010;5:e12272. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0012272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hatami M, Mehrjardi NZ, Kiani S, et al. Human embryonic stem cell-derived neural precursor transplants in collagen scaffolds promote recovery in injured rat spinal cord. Cytotherapy. 2009;11:618–630. doi: 10.1080/14653240903005802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lee SH, Chung YN, Kim YH, et al. Effects of human neural stem cell transplantation in canine spinal cord hemisection. Neurol Res. 2009;31:996–1002. doi: 10.1179/174313209X385626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cummings BJ, Uchida N, Tamaki SJ, et al. Human neural stem cell differentiation following transplantation into spinal cord injured mice: Association with recovery of locomotor function. Neurol Res. 2006;28:474–481. doi: 10.1179/016164106X115116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wennersten A, Meier X, Holmin S, et al. Proliferation, migration, and differentiation of human neural stem/progenitor cells after transplantation into a rat model of traumatic brain injury. J Neurosurg. 2004;100:88–96. doi: 10.3171/jns.2004.100.1.0088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gao J, Prough DS, McAdoo DJ, et al. Transplantation of primed human fetal neural stem cells improves cognitive function in rats after traumatic brain injury. Exp Neurol. 2006;201:281–292. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2006.04.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kim SK, Kim SU, Park IH, et al. Human neural stem cells target experimental intracranial medulloblastoma and deliver a therapeutic gene leading to tumor regression. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12:5550–5556. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-2508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Joo KM, Park IH, Shin JY, et al. Human neural stem cells can target and deliver therapeutic genes to breast cancer brain metastases. Mol Ther. 2009;17:570–575. doi: 10.1038/mt.2008.290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McCaig CD, Rajnicek AM, Song B, et al. Controlling cell behavior electrically: Current views and future potential. Physiol Rev. 2005;85:943–978. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00020.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhao M. Electrical fields in wound healing—An overriding signal that directs cell migration. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2009;20:674–682. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2008.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li L, El-Hayek YH, Liu B, et al. Direct-current electrical field guides neuronal stem/progenitor cell migration. Stem Cells. 2008;26:2193–2200. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2007-1022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Meng X, Arocena M, Penninger J, et al. PI3K mediated electrotaxis of embryonic and adult neural progenitor cells in the presence of growth factors. Exp Neurol. 2011;227:210–217. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2010.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yao L, Shanley L, McCaig C, et al. Small applied electric fields guide migration of hippocampal neurons. J Cell Physiol. 2008;216:527–535. doi: 10.1002/jcp.21431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yao L, McCaig CD, Zhao M. Electrical signals polarize neuronal organelles, direct neuron migration, and orient cell division. Hippocampus. 2009;19:855–868. doi: 10.1002/hipo.20569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Arocena M, Zhao M, Collinson JM, et al. A time-lapse and quantitative modelling analysis of neural stem cell motion in the absence of directional cues and in electric fields. J Neurosci Res. 2010;88:3267–3274. doi: 10.1002/jnr.22502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cormie P, Robinson KR. Embryonic zebrafish neuronal growth is not affected by an applied electric field in vitro. Neurosci Lett. 2007;411:128–132. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2006.10.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hinkle L, McCaig CD, Robinson KR. The direction of growth of differentiating neurones and myoblasts from frog embryos in an applied electric field. J Physiol. 1981;314:121–135. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1981.sp013695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rajnicek AM, Gow NA, McCaig CD. Electric field-induced orientation of rat hippocampal neurones in vitro. Exp Physiol. 1992;77:229–232. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.1992.sp003580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhang J, Calafiore M, Zeng Q, et al. Electrically guiding migration of human induced pluripotent stem cells. Stem Cell Rev. 2011 doi: 10.1007/s12015-011-9247-5. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Song B, Gu Y, Pu J, et al. Application of direct current electric fields to cells and tissues in vitro and modulation of wound electric field in vivo. Nat Protoc. 2007;2:1479–1489. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhao M, Agius-Fernandez A, Forrester JV, et al. Orientation and directed migration of cultured corneal epithelial cells in small electric fields are serum dependent. J Cell Sci. 1996;109(pt 6):1405–1414. doi: 10.1242/jcs.109.6.1405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tai G, Reid B, Cao L, et al. Electrotaxis and wound healing: Experimental methods to study electric fields as a directional signal for cell migration. Methods Mol Biol. 2009;571:77–97. doi: 10.1007/978-1-60761-198-1_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhang SC, Wernig M, Duncan ID, et al. In vitro differentiation of transplantable neural precursors from human embryonic stem cells. Nat Biotechnol. 2001;19:1129–1133. doi: 10.1038/nbt1201-1129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Robinson KR, Cormie P. Electric field effects on human spinal injury: Is there a basis in the in vitro studies? Dev Neurobiol. 2008;68:274–280. doi: 10.1002/dneu.20570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Patel N, Poo MM. Orientation of neurite growth by extracellular electric fields. J Neurosci. 1982;2:483–496. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.02-04-00483.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cork RJ, Mcginnis ME, Tsai J, et al. The growth of PC12 neurites is biased towards the anode of an applied electrical-field. J Neurobiol. 1994;25:1509–1516. doi: 10.1002/neu.480251204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Koyanagi M, Takahashi J, Arakawa Y, et al. Inhibition of the Rho/ROCK pathway reduces apoptosis during transplantation of embryonic stem cell-derived neural precursors. J Neurosci Res. 2008;86:270–280. doi: 10.1002/jnr.21502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Li X, Meng G, Krawetz R, et al. The ROCK inhibitor Y-27632 enhances the survival rate of human embryonic stem cells following cryo-preservation. Stem Cells Dev. 2008;17:1079–1085. doi: 10.1089/scd.2007.0247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Heng BC. Effect of Rho-associated kinase (ROCK) inhibitor Y-27632 on the post-thaw viability of cryopreserved human bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells. Tissue Cell. 2009;41:376–380. doi: 10.1016/j.tice.2009.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rajasekharan S, Bin JM, Antel JP, et al. A central role for RhoA during oligodendroglial maturation in the switch from netrin-1-mediated chemorepulsion to process elaboration. J Neurochem. 2010;113:1589–1597. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2010.06717.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chang TC, Chen YC, Yang MH, et al. Rho kinases regulate the renewal and neural differentiation of embryonic stem cells in a cell plating density-dependent manner. PLoS ONE. 2010;5:e9187. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0009187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rajnicek AM, Foubister LE, McCaig CD. Temporally and spatially coordinated roles for Rho, Rac, Cdc42 and their effectors in growth cone guidance by a physiological electric field. J Cell Sci. 2006;119:1723–1735. doi: 10.1242/jcs.02896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Miller RJ, Banisadr G, Bhattacharyya BJ. CXCR4 signaling in the regulation of stem cell migration and development. J Neuroimmunol. 2008;198:31–38. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2008.04.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.van der Meulen AA, Biber K, Lukovac S, et al. The role of CXC chemokine ligand (CXCL)12-CXC chemokine receptor (CXCR)4 signalling in the migration of neural stem cells towards a brain tumour. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol. 2009;35:579–591. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2990.2009.01036.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Robin AM, Zhang ZG, Wang L, et al. Stromal cell-derived factor 1alpha mediates neural progenitor cell motility after focal cerebral ischemia. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2006;26:125–134. doi: 10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Li Q, Yao D, Ma J, et al. Transplantation of MSCs in combination with Netrin-1 improves neoangiogenesis in a rat model of hind limb ischemia. J Surg Res. 2011;166:162–169. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2009.08.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Aguirre A, Rizvi TA, Ratner N, et al. Overexpression of the epidermal growth factor receptor confers migratory properties to nonmigratory postnatal neural progenitors. J Neurosci. 2005;25:11092–11106. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2981-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Suzuki T, Mandai M, Akimoto M, et al. The simultaneous treatment of MMP-2 stimulants in retinal transplantation enhances grafted cell migration into the host retina. Stem Cells. 2006;24:2406–2411. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2005-0587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Khaldoyanidi S. Directing stem cell homing. Cell Stem cell. 2008;2:198–200. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2008.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Karp JM, Leng Teo GS. Mesenchymal stem cell homing: The devil is in the details. Cell Stem cell. 2009;4:206–216. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2009.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Cheng Z, Ou L, Zhou X, et al. Targeted migration of mesenchymal stem cells modified with CXCR4 gene to infarcted myocardium improves cardiac performance. Mol Ther. 2008;16:571–579. doi: 10.1038/sj.mt.6300374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.