Summary

Infection with Neisseria gonorrhoeae (Gc) is marked by an influx of neutrophils to the site of infection. Despite a robust immune response, viable Gc can be recovered from neutrophil-rich gonorrheal secretions. Gc enzymatically modifies the lipid A portion of lipooligosaccharide by the addition of phosphoethanolamine (PEA) to the phosphate group at the 4’ position. Loss of LptA, the enzyme catalyzing this reaction, increases bacterial sensitivity to killing by human complement and cationic antimicrobial peptides. Here, we investigated the importance of LptA for interactions between Gc and human neutrophils. We found that lptA mutant Gc was significantly more sensitive to killing by human neutrophils. Three mechanisms underlie the increased sensitivity of lptA mutant Gc to neutrophils. 1) lptA mutant Gc is more likely to reside in mature phagolysosomes than LptA-expressing bacteria. 2) lptA mutant Gc is more sensitive to killing by components found in neutrophil granules, including CAP37/azurocidin, human neutrophil peptide 1, and the serine protease cathepsin G. 3) lptA mutant Gc is more susceptible to killing by antimicrobial components that are exocytosed from neutrophils, including those decorating neutrophil extracellular traps. By increasing the resistance of Gc to the bactericidal activity of neutrophils, LptA-catalyzed modification of lipooligosaccharide enhances survival of Gc from the human inflammatory response during acute gonorrhea.

Introduction

Gonorrhea continues to be a global health concern. Over 106 million cases of gonorrhea are estimated annually worldwide, up from 88 million in 2011 (World Health Organization, 2011; World Health Organization, 2012). Neisseria gonorrhoeae (gonococcus, Gc) is the sole, causative agent of gonorrhea, and is one of three bacterial pathogens currently regarded as an “urgent,” highest-level threat by the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC, 2013). Gc has attained “superbug” status based on emerging resistance to third-generation cephalosporins – the last recommended line of disease treatment – and on the continued unavailability of a vaccine (CDC, 2011).

Symptomatic gonorrhea is characterized by a substantial influx of polymorphonuclear leukocytes (PMNs; neutrophils) to the site of infection. Gc can be recovered from PMN-rich gonorrheal exudates and primary human PMNs infected ex vivo (Criss and Seifert, 2012), but the defense mechanisms used by Gc to survive the diverse antimicrobial activities of PMNs are just starting to be defined. Lipooligosaccharide (LOS) is one of the few known virulence factors for Gc and the most abundant surface component (Hobbs et al., 2013). Neisserial LOS is composed of lipid A that anchors the structure to the membrane, which is connected to the inner core sugars, two 3-deoxy-D-manno-octulosonic acid (KDO) residues and two heptoses, from which the outer-core oligosaccharide extends. LOS variation is an important determinant for Gc interactions with the host (Gotschlich, 1994; Shafer et al., 2002; Tzeng et al., 2005; Lewis et al., 2009; Balthazar et al., 2011). Many of the LOS outer-core biosynthetic genes are phase variable, and components of LOS can be enzymatically modified (Gotschlich, 1994; Shell et al., 2002; Cox et al., 2003). One of these modifications is the addition of phosphoethanolamine (PEA) to the 4’ phosphate on lipid A, catalyzed by the phase-variable LOS phosphoethanolamine transferase A (LptA) (Cox et al., 2003; Lewis et al., 2009; Kandler et al., 2014). lptA mutant Gc is more susceptible to bacteriolysis by human complement, and both Gc and Neisseria meningitidis lacking lptA are more susceptible to killing by cationic antimicrobial proteins (CAMPs) (Tzeng et al., 2005; Lewis et al., 2009; Lewis et al., 2013). lptA mutant Gc is attenuated in experimental male infection and cervicovaginal murine challenge (Hobbs et al., 2013; Packiam et al., 2014). Neisseria lipid A lacking the 4’ PEA modification is also less immunostimulatory, causing lower levels of TNFα to be released by human monocytes and less induction of NFκB via Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) (John et al., 2009a; John et al., 2009b; Liu et al., 2010; Packiam et al., 2014). Most Neisseria commensal strains, with the exception of N. lactamica, do not encode a functional lptA gene, and this is hypothesized to contribute to their commensalism (John et al., 2012).

Here, we investigated the contribution of LptA to Gc defense against killing by primary human PMNs. Expression of LptA enhanced Gc survival from the intracellular and extracellular antimicrobial activities of PMNs. Three mechanisms contributed to the survival advantage of LptA-expressing Gc after exposure to PMNs: increased resistance to PMN CAMPs, including CAP37/azurocidin, human neutrophil peptide-1 (HNP-1), and the serine protease cathepsin G; reduced residence in mature phagolysosomes; and increased resistance to the antimicrobial effects of neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs). These results highlight the importance of LptA for Gc survival during interaction with human PMNs.

Results

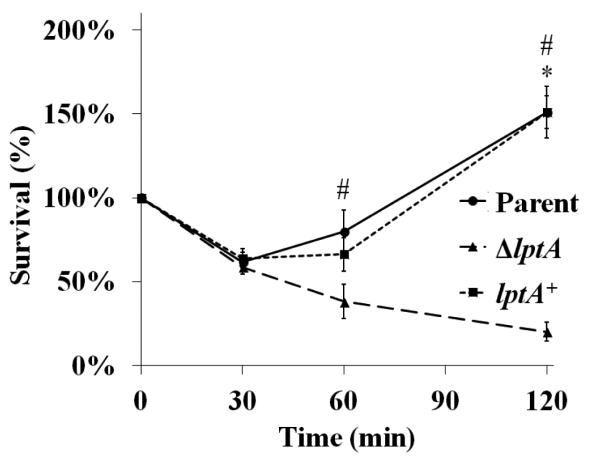

LptA improves survival of N. gonorrhoeae exposed to human PMNs

Piliated, opacity protein-deficient Gc of strain FA1090, an isogenic lptA mutant (ΔlptA), and ΔlptA complemented with full-length lptA under the control of an IPTG-inducible promoter (lptA+) were assessed for their survival in the presence of adherent, IL-8-treated human PMNs (Fig. 1). lptA+ Gc was induced with 250 μM IPTG, which conferred similar resistance to the model cationic antimicrobial peptide polymyxin B as exhibited by parent bacteria (Fig. S1). After exposure to PMNs, approximately 60% of the parent and lptA+ inocula were recovered 30 min after exposure and increased thereafter, reaching approximately 150% of the inocula by 2 h. ΔlptA Gc exhibited a similar decline in survival over 30 min, but unlike the parent and lptA+ strains, it failed to recover at later times, with statistically significant decreases in survival measured at 60 and 120 min post-infection. ΔlptA bacteria remained viable in infection media without PMNs over the same time period (data not shown) and did not show any significant differences in growth in rich liquid media compared to parent and lptA+ Gc (Fig. S2).

Figure 1. LptA is important for survival of Gc exposed to primary human PMNs.

Isogenic FA1090 parent, lptA mutant (ΔlptA), and lptA complement (lptA+) Gc were exposed to adherent, IL-8-primed PMNs. Bacterial survival was calculated by enumerating CFU in PMN lysates at 30, 60, and 120 min divided by CFU at 0 min. *, P<0.05 for parent vs. ΔlptA (*) and #, P< 0.05 for lptA+ vs. ΔlptA, two-tailed t test, n=4 experiments.

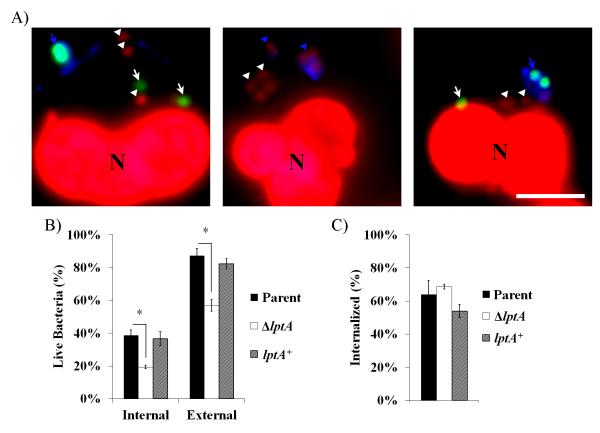

PMNs are equipped with a variety of killing mechanisms that are released both intra- and extracellularly. To further characterize the ΔlptA survival defect, we used dyes that differentially report on the viability of individual bacteria, in combination with a fluorescently-labeled lectin, to differentiate live from dead and intracellular from extracellular Gc (Fig. 2A). ΔlptA Gc exhibited decreased survival both intracellularly and extracellularly compared to parent and lptA+ bacteria after 1 h infection (Fig. 2B). There was no significant difference in internalization by PMNs among the three strains (Fig. 2C). These results indicate that Gc expressing LptA is protected against the killing mechanisms of PMNs in both intracellular and extracellular environments.

Figure 2. LptA improves survival of Gc both intracellularly and extracellularly when exposed to PMNs.

Parent, ΔlptA, and lptA+ Gc were exposed to adherent PMNs for 1 h. A) Gc was stained with an Alexa Fluor 647 conjugated soybean lectin (blue) to detect extracellular bacteria. PMNs were then permeabilized with saponin and exposed to Baclight viability dyes Syto9 (green) and propidium iodide (red) to discriminate viable from non-viable bacteria, respectively. White arrowheads indicate intracellular non-viable Gc, and white arrows indicate viable Gc. Blue arrowheads and arrows indicate extracellular non-viable and viable Gc, respectively. PMN nuclei were also PI+ (N). B) Bacterial viability was quantified for both intracellular and extracellular Gc and is expressed as the percent of total intracellular or extracellular Gc per strain. C) Percent bacterial internalization was calculated by dividing the number of intracellular bacteria (viable and non-viable) by the total number of cell-associated bacteria. Scale bar, 5μm. *, P<0.05 for parent vs. ΔlptA; two-tailed t-test, n= 3 experiments.

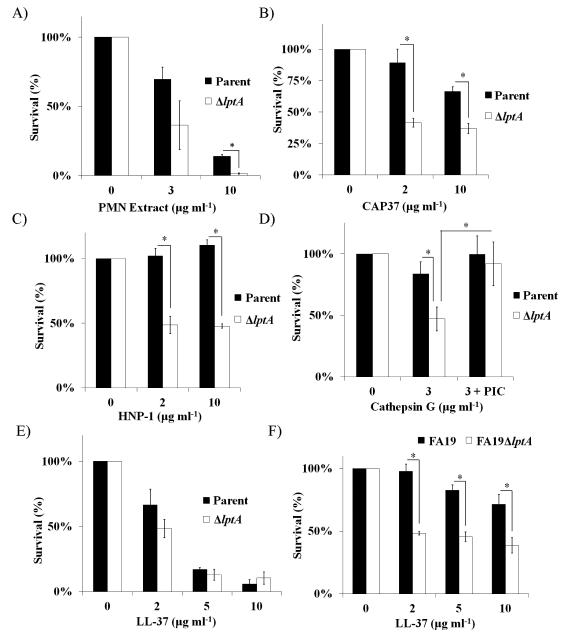

LptA protects Gc from the bactericidal activity of non-oxidative components of human PMNs

PMNs use non-oxidative components including proteases and antimicrobial peptides to combat Gc (Shafer et al., 1986b; Shafer et al.,1986c; Criss et al., 2009; Johnson and Criss, 2013). It has been shown that lptA mutants in Gc and N. meningitidis are more sensitive to some of these components, due to loss of PEA on lipid A (Tzeng et al., 2005; Lewis et al., 2009). To test the hypothesis that the reduced survival of ΔlptA Gc after exposure to PMNs was due to increased sensitivity to PMN granule proteins, parent, ΔlptA, and lptA+ Gc were exposed to an extract made from the cytoplasmic granules of PMNs. The purified PMN extract exhibited anti-gonococcal activity, and ΔlptA Gc was significantly more susceptible to the extract than parent Gc (Fig. 3A). We therefore examined components found in PMN granules for their activity against parent and ΔlptA Gc. The lptA mutant had increased sensitivity to all three of the primary (azurophilic) granule components tested (Fig. 3B-D). CAP37 had modest antimicrobial activity against parental Gc, in keeping with previous reports (Shafer et al., 1986a), but was significantly more active against ΔlptA Gc (Fig. 3B). The α-defensin HNP-1 had no activity against parental Gc, as previously reported (Qu et al., 1996); however, ΔlptA Gc was sensitive to it (Fig. 3C). The serine protease cathepsin G had minor bactericidal activity against parent Gc, but was significantly more effective at killing ΔlptA bacteria (Fig. 3D). The increased sensitivity of ΔlptA Gc to cathepsin G was due in part to its protease activity (Fig. 3D). In contrast, the contribution of LptA to protection from the CAMP LL-37 depended on the bacterial strain background: there was no difference in sensitivity to LL-37 for FA1090 parent and ΔlptA Gc (Fig. 3E), but as previously reported (Lewis et al., 2009; Lewis et al., 2013), an lptA mutant in strain FA19 was significantly more sensitive to LL-37 compared with its parent (Fig. 3F). FA1090 ΔlptA Gc was also significantly more sensitive to polymyxin B than its parent (Fig. S1). Taken together, these results show that expression of LptA increases Gc defense against some of the non-oxidative components made by PMNs, and this is influenced by the bacterial genetic background.

Figure 3. LptA is important for Gc defense against non-oxidative components produced by PMNs.

Parent and ΔlptA Gc in the FA1090 genetic background were exposed to the indicated concentrations of A) purified PMN extract, B) CAP37, C) HNP-1, D) Cathepsin G (+/− 1x protease inhibitor cocktail, PIC) or E) LL-37. In F) parent and ΔlptA Gc of strain FA19 were exposed to the indicated concentrations of LL-37. Survival at each concentration is expressed relative to bacterial survival in the untreated control. *, P<0.05 for indicated comparisons; Student’s two-tailed t test, n=3 biological replicates per strain.

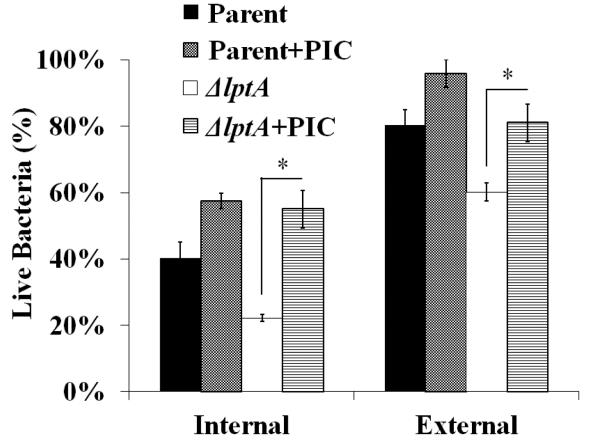

We previously showed that primary granule serine protease activity contributes to the killing of Gc inside PMNs (Johnson and Criss, 2013). To test whether serine proteases contribute to the increased sensitivity of ΔlptA Gc to PMNs, bacterial survival was measured in PMNs treated with a protease inhibitor cocktail. Treatment with the protease inhibitors significantly improved the intracellular and extracellular survival of ΔlptA Gc after exposure to PMNs, to levels indistinguishable from parent Gc (Fig. 4). Thus serine proteases such as cathepsin G also have antigonococcal activity in the context of PMN infection, and LptA is important for Gc defense against them.

Figure 4. LptA protects N. gonorrhoeae from killing mediated by protease activity in PMNs.

Adherent PMNs were pre-treated with protease inhibitor cocktail (PIC) or mock-treated, then exposed to Gc for 1 h. Intracellular and extracellular Gc viability was measured using fluorescent dyes as in Figure 2. *, P<0.05 for ΔlptA vs. ΔlptA + PIC; two-tailed t-test, n=3 experiments.

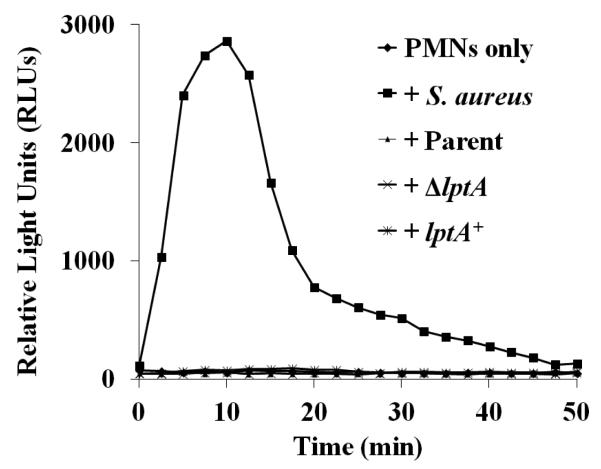

We also explored whether there were differences in the ability of PMNs to mount an oxidative burst after exposure to ΔlptA Gc. As we previously reported, the opacity protein-deficient parent Gc strain used here did not stimulate release of ROS by PMNs (Fig. 5). Neither ΔlptA nor lptA+ Gc induced detectable ROS from PMNs, but PMNs were otherwise able to generate ROS, shown using Staphylococcus aureus as a positive control (Fig. 5). Thus differences in ROS production do not contribute to the survival defect of ΔlptA Gc after exposure to PMNs.

Figure 5. No PMN oxidative burst in response to parent or ΔlptA Gc.

PMNs were uninfected or exposed to the indicated Gc strains or opsonized S. aureus. The production of ROS was detected by luminol-dependent chemiluminescence over time. The graph is a representative replicate from one of three experiments.

LptA-deficient N. gonorrhoeae are more frequently found in mature, primary granule-positive PMN phagolysosomes

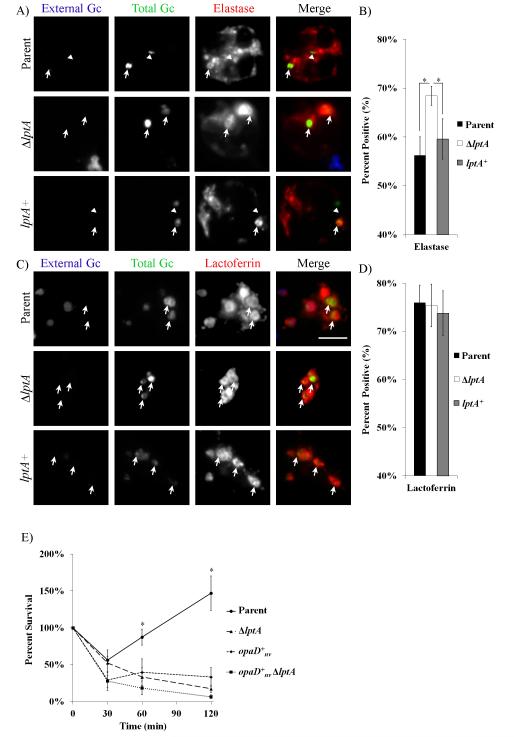

PMN phagosomes containing opacity protein-negative Gc exhibit delayed maturation due to reduced fusion with primary granules, but not secondary (specific) granules (Johnson and Criss, 2013). Phagosomes containing ΔlptA Gc exhibited a statistically significant increase in primary granule enrichment compared to the parent, with no appreciable difference in secondary granule enrichment (Fig. 6A-D).

Figure 6. Decreased maturation of phagosomes containing LptA-expressing Gc.

CFSE-stained parent, ΔlptA, and lptA+ Gc were exposed to adherent PMNs for 1 h. Extracellular and intracellular Gc were identified by accessibility to an anti-Gc antibody before and after PMN permeabilization. Granule enrichment was assessed as described in Experimental Procedures using antibodies against A) neutrophil elastase for primary granules or C) lactoferrin for secondary granules. Extracellular Gc appears blue and green, intracellular Gc appears green only, and granule proteins appear red. Granule enrichment was quantified for B) neutrophil elastase and D) lactoferrin. *, P < 0.05 for the indicated pairs by two-tailed t-test, n=3 experiments. E) Parent, ΔlptA, opaD+nv and opaD+nv ΔlptA Gc were exposed to PMNs, and Gc survival over time was enumerated as in Fig. 1.*, P < 0.05 for parent vs . ΔlptA, opaD+nv or opaD+nv ΔlptA); Student’s two-tailed t-test, n=3 experiments.

To test if increasing the exposure of ΔlptA Gc to primary granule components would further compromise its survival, the lptA deletion was introduced into the opaD+nv Gc background. We recently reported that PMN phagosomes containing Opa+ Gc have significantly increased enrichment of primary granule components (Johnson et al., 2014). The survival of opaD+nv ΔlptA Gc was reduced relative to ΔlptA Gc and opaD+nv Gc after exposure to PMNs, although the differences were not statistically significant (Fig. 6E). Taken together, we conclude that increased residence of ΔlptA Gc in primary granule-rich phagolysosomes, in addition to the increased sensitivity of ΔlptA Gc to primary granule components, contributes to the survival defect of the mutant inside PMNs.

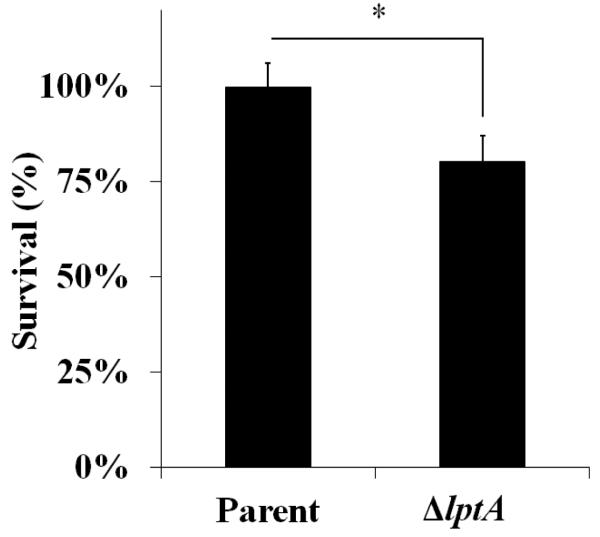

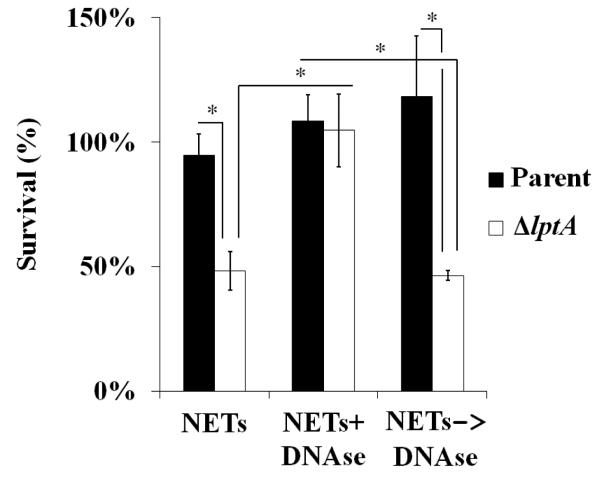

LptA protects Gc from killing by extracellular PMN components

Since ΔlptA Gc is also more sensitive to extracellular killing by PMNs (Fig. 2), we tested the susceptibility of parent and ΔlptA Gc to the two approaches used by PMNs to combat extracellular microorganisms: degranulation and NET formation (Johnson and Criss, 2011). First, PMNs were stimulated with PMA to promote exocytosis of all granule types, and Gc were incubated with the degranulated supernatant. ΔlptA Gc was significantly more sensitive to the degranulated supernatant than the parent, which had no loss in viability (Fig. 7). Second, to induce NETs, PMNs were stimulated with PMA, in the presence of cytochalasin D to block phagocytosis. ΔlptA Gc was more sensitive than parent Gc to killing by PMNs that release NETs. Importantly, ΔlptA Gc survival was rescued by the addition of DNAse I to degrade NET DNA (Fig. 8). Treatment of NETs with DNAse I after infection did not rescue the survival defect of ΔlptA Gc, implying that NETs had antimicrobial activity against ΔlptA Gc, rather than trapping the mutant and preventing accurate colony counts (Fig. 8). Taken together, these results show that LptA protects Gc from degranulation and NETs, thereby hampering the ability of PMNs to combat extracellular Gc.

Figure 7. LptA improves resistance of Gc to killing by the degranulated supernatant of human PMNs.

Parent and ΔlptA Gc were exposed to supernatant from PMA-treated PMNs for 45 min (equivalent of supernatant from 2.5 x 105 degranulated cells). The percent of bacteria surviving supernatant treatment is expressed relative to the no treatment control. *, P < 0.05; Student’s two-tailed t-test, n=3 experiments.

Figure 8. LptA enhances the resistance of Gc to the antimicrobial effects of NETs.

Parent and ΔlptA Gc were exposed to PMNs that were treated with PMA to release NETs. NETs were either left untreated, treated with DNAse I prior to infection with Gc (NETs+DNAse), or treated with DNAse I after infection with Gc (NETs ✧ DNase). Bacterial survival was calculated by dividing the CFU after 60 min exposure by the CFU at 0 min. *, P<0.05; two-tailed t-test, n=3 experiments.

Discussion

The mechanisms Gc uses to resist the robust antimicrobial activities of PMNs are beginning to be elucidated. The LOS-modifying enzyme LptA is only one of a few known virulence factors that promote Gc pathogenesis, since LptA is crucial for Gc survival following infection of the human male urethra or the murine cervix (Hobbs et al., 2013; Packiam et al., 2014). Here we demonstrate that LptA also improves Gc defense from killing by primary human PMNs, and does so in three distinct ways: increasing Gc resistance to non-oxidative PMN components, including from degranulated PMNs, avoiding Gc residence in mature phagolysosomes, and enhancing Gc survival in NETs. Gc with PEA-modified lipid A also shows increased binding of factor H and C4BP (Lewis et al., 2013), implying that LptA would also contribute to the resistance of Gc to complement-mediated killing and opsonophagocytosis by PMNs. Through these complementary mechanisms, LptA provides a crucial advantage for survival of Gc after exposure to PMNs, thus facilitating bacterial persistence in its obligate human hosts.

Given that LptA has been reported to provide Gc with defense against CAMPs in vitro (Tzeng et al., 2005; Balthazar et al., 2011; Packiam et al., 2014), we hypothesized that LptA would help protect Gc from PMNs by enhancing its resistance to PMN-derived CAMPs. We found that LptA-expressing Gc is significantly more resistant to killing by a purified PMN granule extract as well as the degranulated supernatant from activated PMNs. PMN granules contain a variety of membrane-associated and soluble components designed to detect and eliminate threats to the host. Prevalent among these are CAMPs such as α-defensins, CAP37, and serine proteases. CAMPs disrupt the bacterial membrane through charge-charge interactions and also have regulatory effects on immune events (Steinstraesser et al., 2011). Here we found that LptA protects Gc from killing by two CAMPs, CAP37 and HNP-1. Although CAP37 was one of the first antigonococcal proteins to be identified (Shafer et al., 1986c), , LptA is the first defined Gc gene product to be shown to modulate Gc sensitivity to CAP37. Gc is highly resistant to HNP-1 (Qu et al., 1996), and here we show that one of the major contributors to this resistance is LptA. Serine proteases can have direct antimicrobial activity, process precursor proteins into their active forms (Sørensen et al., 2001) and facilitate innate and adaptive immune responses (Pham, 2006; Mantovani et al., 2011). We found that LptA expression was particularly important for Gc defense against killing by cathepsin G, due in part to its serine protease activity. Since the protease inhibitor cocktail used here can inhibit all PMN serine proteases, LptA may also help defend Gc against neutrophil elastase and proteinase 3, although they have not been reported to have direct antigonococcal activity akin to cathepsin G.

The role of serine proteases in the killing of ΔlptA Gc may be linked not only to their direct antimicrobial activity, but also to their processing of host precursor proteins into their active antimicrobial forms. Cathepsin G has protease-independent antigonococcal activity (Shafer et al., 1986c) by its similarity in sequence and predicted structure with other PMN CAMPs (Shafer et al., 1993). Serine protease activity may be needed to cleave full-length cathepsin G into a bioactive CAMP-like fragment that is more active against ΔlptA bacteria. Gc is also sensitive to the CAMP LL-37, which is cleaved from the hCAP18 precursor by the serine protease proteinase 3 (Sørensen et al., 2001). Strikingly, we found that loss of lptA had no effect on the sensitivity of Gc strain FA1090 to killing by LL-37. This is in contrast to increased sensitivity to LL-37 by ΔlptA Gc in the FA19 strain background (Packiam et al., 2014). This discrepancy may be due to differences in expression of the MtrCDE multidrug efflux pump in these two strain backgrounds. FA1090 has a natural mutation in the mtrA activator of MtrCDE expression, rendering the strain more sensitive to LL-37 and other compounds that are normally expelled by the pump (Rouquette et al., 1999). Thus FA1090 may already have such sensitivity to LL-37 that loss of lptA has no increased effect. FA1090 and FA19 also produce different oligosaccharide α chains on their LOS species, which may affect intrinsic sensitivity of these strains to LL-37 and other CAMPs (Shafer et al., 2002; Hobbs et al., 2013).

Since our working hypothesis was that LptA protects Gc from PMNs by providing defense against PMN-derived CAMPs, we were surprised to find that LptA also contributed to Gc residing in immature phagosomes inside PMNs. We previously reported that the fraction of Gc surviving inside PMNs are found in phagosomes that exhibit delayed fusion with primary granules to avoid becoming degradative phagolysosomes (Johnson and Criss, 2013). Residence in immature phagosomes did not require actively growing Gc, suggesting a surface structure influenced phagosome composition, perhaps by affecting the bacterial entry process. Our findings suggest that LOS may be one such structure, and LOS composition, including 4’ PEA decoration of lipid A, affects PMN processes leading to phagosome-granule fusion. There are at least two possibilities that could explain how LptA-modified LOS affects phagocytosis and phagosome dynamics. First, direct detection of LptA-modified LOS by PMNs could modulate signaling events that are important for phagosome-granule fusion. Second, LptA-modified lipid A could affect the surface presentation of LOS oligosaccharide chains or other outer membrane components, which are the structures that affect PMN activation and granule mobilization. In either scenario, since primary granules contain cathepsin G and other PMN serine proteases, we conclude that the decreased survival of ΔlptA Gc inside PMNs is due to increased exposure to these components as well as increased intrinsic susceptibility to them.

LptA also contributes to Gc survival extracellularly after PMN challenge by protecting the bacteria from the antimicrobial components released by exocytosis and on NETs. Primary human PMNs release NETs after exposure to Gc (R.A. Juneau, J.S. Stevens, M.A. Apicella, and A.K. Criss, 2015). Loss of lptA in the related bacterium N. meningitidis has been shown to decrease bacterial growth in the presence of NETs, due to NET-associated CAMPs such as cathepsin G (Lappann et al., 2013). We found that ΔlptA Gc has an extracellular survival defect in the presence of PMNs that had undergone NET release. Inhibiting the protease activity of cathepsin G and digesting the PMN NET backbone with DNase both rescue the survival of extracellular ΔlptA Gc. Taken together, we conclude that LptA expression improves extracellular survival of Gc against concentrated PMN CAMPs, including those incorporated into NETs.

The role of LptA in Neisserial biology is intriguing. Most commensal Neisseria strains do not encode a functional lptA gene (John et al., 2012), while Gc and N. meningitidis do (Cox et al., 2003; Tzeng et al., 2005; Lewis et al., 2009). 4’ PEA-modified lipid A is a better ligand for TLR4 and thus initiates stronger inflammatory signals than unmodified Neisserial lipid A (John et al., 2009a; John et al., 2009b; Liu et al., 2010; Packiam et al., 2014). This would seem to be counterintuitive: while many bacterial pathogens attempt to escape detection by their hosts, the pathogenic Neisseria produce LOS species that are pro-inflammatory and likely to contribute to the influx of PMNs during acute gonorrhea or meningitis. We posit that LptA is an important virulence determinant for the pathogenic Neisseria, since the same LOS modification that promotes a highly inflammatory, PMN-rich environment confers resistance to the CAMPs and other antimicrobial products found within it. LptA-expressing Gc that are engulfed by PMNs avoid trafficking into mature PMN phagolysosomes and have increased resistance to the CAMPs encountered in phagosomes. Gc that remain extracellular to PMNs can gather nutrients from surrounding host tissue that has been damaged or made leaky as a result of the potent PMN response, while resisting killing by NETs and exocytosed CAMPs (Criss and Seifert, 2012). Thus LptA expression is a double-edged sword during gonorrheal infection, contributing in multiple ways to the extraordinary success of Gc in the human population.

Experimental Procedures

Bacterial strains and growth conditions

Constitutively piliated, opacity protein-deficient (“Opaless”) Gc of strain FA1090 served as the parent for these studies unless otherwise indicated (Ball and Criss, 2013). The phase-variable lptA gene (7-thymidine repeat) is in-frame in Opaless Gc. The Opaless Gc derivative constitutively expressing OpaD was previously described (Opaless::opaD+nv, Ball and Criss, 2013). Gc was maintained on gonococcal medium base (BD Difco) with Kellogg’s supplement I+II (GCB) (Kellogg et al., 1963) and regularly grown in rich liquid medium (GCBL) for 16-20 h at 37°C/5%CO2 (Criss and Seifert, 2008). FA19 parent and ΔlptA Gc were a kind gift of William Shafer (Emory University). TOP10 E. coli and Staphylococcus aureus ATCC 25923 were regularly cultured on Luria-Bertani (LB) agar and grown in LB broth for 16-20 h at 37°C. In these studies, Gc was not opsonized with human serum because of the reported high sensitivity of the lptA mutant to killing by human complement (Lewis et al., 2013). S. aureus was opsonized with 20% freshly isolated human serum for 20 min at 37°C prior to experimental use.

Construction of lptA mutant and complement strains

FA1090 Gc was transformed with a plasmid containing insertionally inactivated lptA. The inactivated lptA gene fragment was constructed using overlap extension PCR (Heckman and Pease, 2007). A fragment of <1 kb comprised of the region upstream of lptA and the 5’ end of the gene (F1) was amplified from Opaless Gc gDNA using the primer pair LPTAF (5’-GTT GCA GAC CGG TTC GAA TTT TGC-3’) and LPTAF1R (5’-GCT TCT GTA TGG AAC GGG CAG TTA ACG ATG GGT TAC TGA TTT ATT GTT GCG G-3’). A second fragment, containing the 3’ end of lptA and downstream sequence (F2), was amplified using the primer pair LPTAF2F (5’-GCT CAC AGC CAA ACT ATC AGG TAG CGC TCT CAACCT GCC CGA ATA CTG C-3’) and LPTAR (5’-TTC AAC ACA TCG CGA AAA CGT TGC-3’). An omega-spectinomycin resistance cassette (Ω) was amplified using the primer pair ΩLPTAF(5’-CCG CAA CAA TAA ATC AGT AAC CCA TCG TTA ACT GCC CGT TCC ATA CAG AAG C-3’) and ΩLPTAR (5’-GCA GTA TTC GGG CAG GTT GAG AGC GCT ACC TGA TAG TTT GGC TGT GAG C-3’). F1 and Ω PCR fragments were mixed in equimolar ratios and amplified using LPTAF and ΩLPTAR. The overlap extension PCR product (F1- Ω) and F2 were ligated separately into pCR™4Blunt-TOPO® vector (Life Technologies), following manufacturer’s suggestions. TOP10 E. coli were transformed with the F1- Ω ligation product or with the F2 ligation product and selected for on LB agar containing 100 μg ml−1 spectinomycin or 60 μg ml−1 kanamycin, respectively. Transformed colonies were grown in LB broth, and the plasmids were purified using the QIAPrep Spin Miniprep Kit (Qiagen). F1-Ω-pBLUNT was restriction enzyme-digested using AfeI and XbaI (New England Biolabs) and F2 was restriction enzyme-digested using SpeI and AfeI (New England Biolabs) The F1-Ω insert and F2-pBLUNT were ligated together with T4 DNA Ligase (New England Biolabs), following manufacturer’s suggestions. F1-Ω-F2 (lptA::spc)-pBLUNT was purified from TOP10 E. coli that had been transformed with the ligation product and selected for on 100 μg ml−1 spectinomycin. The plasmid construct was introduced into Opaless and Opaless::opaD+nv Gc by natural transformation on solid medium (Stohl and Seifert, 2001), and transformed bacteria were selected on GCB agar containing 30 μg ml−1 spectinomycin. Transformants were confirmed by PCR and sequencing with the primer pair LPTASEQ2F (5’-GTG CGG CGG TGT CTT ACC AAG-3’) and LPTASEQ3R (5’-CGA TTT CGT TGG TAT CGC ATG TC-3’).

To complement FA1090ΔlptA::spc, the bacteria were transformed with the pGCC4 complementation plasmid containing the isopropyl-β-D-galactosidase (IPTG)-inducible lptA gene (from William Shafer, Emory University; as described in (Lewis et al., 2009)). Transformants were selected on GCB agar containing 0.25 μg ml−1 erythromycin. The lptA complement was induced by growing the bacteria in rich liquid medium containing 250 μM IPTG for 2.5 h. At this concentration, the induced bacteria showed similar resistance to polymyxin B as the isogenic parent (Fig. S1).

PMN Isolation

Venous blood was drawn from healthy human donors that had given informed consent in accordance with a protocol approved by the Virginia Institutional Review Board for Health Sciences Research. Heparinized blood, depleted of erythrocytes by dextran sedimentation, was then purified over a Ficoll-Hypaque gradient to isolate PMNs (Stohl et al., 2005). PMNs were resuspended in Dulbecco’s PBS (without Calcium and Magnesium; Thermo Scientific) containing 0.1% dextrose, and kept on ice for < 2 h before use. Preparations were normally >95% PMNs by phase-contrast microscopy.

PMN Antimicrobial Assay

106 IL-8-treated (10nM, R&D Systems) PMNs were allowed to adhere to tissue culture-treated 13mm plastic coverslips in RPMI (Mediatech) containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Thermo Scientific), for 1 h at 37°C/5% CO2. PMNs were then synchronously infected with exponential-phase Gc at a multiplicity of infection of 1-5 as described previously (Criss et al., 2009). At indicated time points, PMNs were lysed in 1% saponin, and Gc was plated on GCB agar. Percent survival was calculated as the CFU at each time divided by the CFU at time 0.

PMN granule extract

Proteins were extracted from PMN cytoplasmic granules using a protocol adapted from Rest (Rest, 1979). Freshly isolated PMNs were resuspended in 0.34 M sucrose and sheared by 15-25 passages through a ball bearing homogenizer until 90-95% breakage was achieved, as indicated by trypan blue staining. The homogenate was centrifuged at 200 x g for 15 min to remove nuclear and cellular debris, then at 20,000xg for another 15 min to pellet the granules. Pellets were resuspended in acetate buffer (0.2M, pH 4.0) and acid-extracted overnight at 4°C twice, then clarified by high-speed centrifugation as above. The extract was stored in acetate buffer at 4°C and was used within 4 weeks of purification. The extract was dialyzed against PBS (8mM NaCl, 12mM K2HPO4, 4mM KH2PO4; pH 7.2) overnight in 3,500 MWCO dialysis tubing (Spectra/Por) prior to experiments.

Viability of bacteria in association with PMNs

Baclight viability dyes (Invitrogen) were used to assess Gc survival intracellularly and extracellularly in the presence of PMNs as described (Criss et al., 2009). In some experiments, PMNs were treated with 1x Protease Inhibitor Cocktail Set V containing AEBSF, aprotinin, E-64, and leupeptin (Calbiochem) during attachment to coverslips and throughout the infection.

CAMP Bactericidal Assay

5x105 CFU of mid-logarithmic Gc were exposed to the indicated concentrations of Polymyxin B (Alexis Biomedicals), CAP37 (Sigma), HNP-1 (Sigma), Cathepsin G (MP Biomedicals), LL-37 (generously provided by William Shafer, Emory University) or PMN granule extract in 0.2x strength GCBL for 45 min at 37°C/5%CO2. Cathepsin G was also incubated with 1x protease inhibitors for 30 min prior to and throughout the assay. Survival was calculated by enumerating CFU at time 0 and time 45 min to yield percent Gc survival for each concentration, then normalized to Gc survival in the untreated control (set to 100%).

PMN Phagosome Maturation

Immunofluorescence imaging of granule enrichment at Gc phagosomes was performed as described (Johnson and Criss, 2013). Prior to infection, Gc were incubated with CFSE to stain total bacteria. Extracellular Gc were detected using an anti-Gc antibody (Biosource) and secondary Alexa Fluor-coupled secondary antibody without PMN permeabilization. Granule enrichment was assessed in permeabilized PMNs with a monoclonal antibody against neutrophil elastase for primary granules (AHN10, Invitrogen) or a polyclonal anti-lactoferrin antibody (MP Biomedicals) for secondary granules, followed by Alexa Fluor-coupled secondary antibody. Cells were examined on a LSM510 confocal laser scanning microscope (Zeiss). Bacterial phagosomes were scored as positive for granule enrichment when the antibody staining for the granule component surrounded ≥50% of the bacterial circumference.

PMN supernatant antimicrobial assay

106 PMA-primed (10nM, Sigma) PMNs were allowed to adhere to tissue culture-treated 13mm plastic coverslips in 0.4 ml RPMI (Mediatech) containing 10% FBS for 30 min at 37°C/5% CO2. The supernatant was filtered (0.2 μM) to remove any PMNs. 106 Gc was incubated with 0.1 ml supernatant or RPMI for 45 min at 37°C/5%CO2. Bacteria were plated on GCB agar, and incubated overnight. Survival was calculated by dividing the percent survival of CFU in a treated condition by the percent survival of CFU in the untreated control.

Gc survival in NETs

Adherent PMNs were exposed to 10nM PMA for 30 min, then treated with cytochalasin D (10 μg ml−1, Sigma) in the presence or absence of DNaseI (1 U ml−1, NEB) for 20 min at 37°C/5%CO2 or were treated with DNAse I (1 U ml−1) after the 1 h infection.. PMNs were then exposed to Gc at MOI = 1 for 1 h. Bacterial survival was calculated relative to CFU enumerated at 0 min for each condition.

ROS detection

PMNs were left untreated or exposed to Gc or serum-opsonized S. aureus at an MOI of 100. ROS production was measured by luminol-dependent chemiluminescence as described previously (Ball and Criss, 2013).

Bacterial growth

Liquid-grown Gc was diluted to an O.D. of 0.07 in modified GCBL. Liquid cultures were grown, shaking, for 4 h at 37 °C. Growth was measured hourly by optical density and plating of bacteria on GCB agar for CFU enumeration.

Statistics

Values are mean ± standard error of three independent replicates (unless otherwise noted). Significance was assessed using the student’s two-tailed t-test. A P-value of less than 0.05 was considered significant.

Supplementary Material

Supplemental Figure Legends

Figure S1. Survival of parent, lptA mutant, and lptA complemented Gc induced with increasing concentrations of IPTG after exposure to polymyxin B. Parent, ΔlptA, and lptA+ complement were grown in the presence of IPTG at the indicated concentrations for 2.5 h, then exposed to 2μg ml−1 polymyxin B. Survival of Gc after 45 min is expressed as a percent of bacterial CFU at 0 min. *, P<0.05; Student’s two-tailed t-test, n=3 biological replicates per strain.

Figure S2. Growth is not attenuated in lptA mutant Gc. Broth-grown parent, ΔlptA, and lptA+ Gc were diluted to an OD550 of 0.07 and incubated over 4 h with shaking. Growth was assessed every hour by A) enumeration of CFU and B) optical density (550nm). n=4 biological replicates per strain.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by NIH R00 TW008042 and R01 AI097312 and the University of Virginia Fund for Excellence in Science and Technology to A.K.C. J.W.H. was supported in part by NIH T32 AI007046. We acknowledge Stephanie Ragland for contributing to generation of the lptA mutant and Richard Juneau for advice on NETs. We are grateful to William Shafer (Emory University) for generous gifts of strains, lptA complementation plasmid, and LL-37, and David Castle (University of Virginia) for advice and use of the ball-bearing homogenizer. We thank William Shafer and members of the Criss laboratory for critical evaluation of the manuscript and its results. The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- Ball LM, Criss AK. Constitutively Opa-expressing and Opa-deficient Neisseria gonorrhoeae strains differentially stimulate and survive exposure to human neutrophils. J Bacteriol. 2013;195:2982–90. doi: 10.1128/JB.00171-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balthazar JT, Gusa A, Martin LE, Choudhury B, Carlson R, Shafer WM. Lipooligosaccharide Structure is an Important Determinant in the Resistance of Neisseria gonorrhoeae to Antimicrobial Agents of Innate Host Defense. Front Microbiol. 2011;2:30. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2011.00030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CDC Cephalosporin susceptibility among Neisseria gonorrhoeae isolates - United States, 2000-2010. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2011;60:873–77. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CDC Antibiotic resistance threats in the United States. 2013 [WWW document]. URL http://www.cdc.gov/drugresistance/threat-report-2013/pdf/ar-threats-2013-508.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Cox AD, Wright JC, Li J, Hood DW, Moxon ER, Richards JC. Phosphorylation of the Lipid A Region of Meningococcal Lipopolysaccharide?: Identification of a Family of Transferases That Add Phosphoethanolamine to Lipopolysaccharide. J Bacteriol. 2003;185:3270–77. doi: 10.1128/JB.185.11.3270-3277.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Criss AK, Katz BZ, Seifert HS. Resistance of Neisseria gonorrhoeae to non-oxidative killing by adherent human polymorphonuclear leucocytes. Cell Microbiol. 2009;11:1074–87. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2009.01308.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Criss AK, Seifert HS. Neisseria gonorrhoeae suppresses the oxidative burst of human polymorphonuclear leukocytes. Cell Microbiol. 2008;10:2257–70. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2008.01205.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Criss AK, Seifert HS. A bacterial siren song: intimate interactions between Neisseria and neutrophils. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2012;10:178–90. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gotschlich E. Genetic locus for the variable portion of Neisseria gonorrhoeae lipooligosaccharide. 1994;180:2181–2190. doi: 10.1084/jem.180.6.2181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heckman KL, Pease LR. Gene splicing and mutagenesis by PCR-driven overlap extension. Nat Protoc. 2007;2:924–32. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hobbs MM, Anderson JE, Balthazar JT, Kandler JL, Carlson RW, Ganguly J, et al. Lipid A’ s Structure Mediates Neisseria gonorrhoeae Fitness During Experimental Infection of Mice and Men. MBio. 2013;19:e00892–13. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00892-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- John CM, Liu M, Jarvis GA. Profiles of structural heterogeneity in native lipooligosaccharides of Neisseria and cytokine induction. J Lipid Res. 2009a;50:424–38. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M800184-JLR200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- John CM, Liu M, Jarvis GA. Natural phosphoryl and acyl variants of lipid A from Neisseria meningitidis strain 89I differentially induce tumor necrosis factor-alpha in human monocytes. J Biol Chem. 2009b;284:21515–25. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.004887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- John CM, Liu M, Phillips NJ, Yang Z, Funk CR, Zimmerman LI, et al. Lack of lipid A pyrophosphorylation and functional lptA reduces inflammation by Neisseria commensals. Infect Immun. 2012;80:4014–26. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00506-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson MB, Ball LM, Daily KP, Martin JN, Columbus L, Criss AK. Opa+ Neisseria gonorrhoeae exhibits reduced survival in human neutrophils via Src family kinase-mediated bacterial trafficking into mature phagolysosomes. Accepted, Cell Microbiol. 2014 Oct 27; doi: 10.1111/cmi.12389. doi: 10.1111/cmi.12389 [Epub] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson MB, Criss AK. Resistance of Neisseria gonorrhoeae to neutrophils. Front Microbiol. 2011;2:77. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2011.00077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson MB, Criss AK. Neisseria gonorrhoeae phagosomes delay fusion with primary granules to enhance bacterial survival inside human neutrophils. Cell Microbiol. 2013;15:1323–40. doi: 10.1111/cmi.12117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kandler JL, Sandeep J, Balthazar JT, Dhulipala V, Read TD, Jerse AE, Shafer WM. Phase-Variable Expression of lptA Modulates the Resistance of Neisseria gonorrhoeae to Cationic Antimicrobial Peptides. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2014;58:4230–3. doi: 10.1128/AAC.03108-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kellogg DS, Peacock WL, Deacon WE, Brown L, Pirkle DI. Neisseria gonorrhoeae. I. Virulence Genetically Linked To Clonal Variation. J Bacteriol. 1963;85:1274–9. doi: 10.1128/jb.85.6.1274-1279.1963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lappann M, Danhof S, Guenther F, Olivares-Florez S, Mordhorst IL, Vogel U. In vitro resistance mechanisms of Neisseria meningitidis against neutrophil extracellular traps. Mol Microbiol. 2013;89:433–49. doi: 10.1111/mmi.12288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis LA, Choudhury B, Balthazar JT, Martin LE, Ram S, Rice PA, et al. Phosphoethanolamine substitution of lipid A and resistance of Neisseria gonorrhoeae to cationic antimicrobial peptides and complement-mediated killing by normal human serum. Infect Immun. 2009;77:1112–20. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01280-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis LA, Shafer WM, Ray TD, Ram S, Rice PA. Phosphoethanolamine residues on the lipid A moiety of Neisseria gonorrhoeae lipooligosaccharide modulate binding of complement inhibitors and resistance to complement killing. Infect Immun. 2013;81:33–42. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00751-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu M, John CM, Jarvis GA. Phosphoryl moieties of lipid A from Neisseria meningitidis and N. gonorrhoeae lipooligosaccharides play an important role in activation of both MyD88- and TRIF-dependent TLR4-MD-2 signaling pathways. J Immunol. 2010;185:6974–84. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1000953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mantovani A, Cassatella MA, Costantini C, Jaillon S. Neutrophils in the activation and regulation of innate and adaptive immunity. Nat Rev Immunol. 2011;11:519–31. doi: 10.1038/nri3024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Packiam M, Yedery R, Begum AA, Carlson RW, Ganguly J, Sempowski GD, et al. Phosphoethanolamine Decoration of Neisseria gonorrhoeae Lipid A Plays a Dual Immunostimulatory and Protective Role during Experimental Genital Tract Infection. Infect Immun. 2014;82(6):2170–9. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01504-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pham CTN. Neutrophil serine proteases: specific regulators of inflammation. Nat Rev Immunol. 2006;6:541–50. doi: 10.1038/nri1841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qu X, Harwig SSL, Oren AMI, Shafer WM, Lehrer RI. Susceptibility of Neisseria gonorrhoeae to Protegrins. Infect Immun. 1996;64:1240–1245. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.4.1240-1245.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rest RF. Killing of Neisseria gonorrhoeae by human polymorphonuclear neutrophil granule extracts. Infect Immun. 1979;25(2):574–9. doi: 10.1128/iai.25.2.574-579.1979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rouquette C, Harmon JB, Shafer WM. Induction of the mtrCDE-encoded efflux pump system of Neisseria gonorrhoeae requires MtrA, an AraC-like protein. Mol Microbiol. 1999;33:651–8. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01517.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shafer WM, Datta A, Kolli VSK, Rahman MM, Balthazar JT, Martin LE, et al. Phase variable changes in genes lgtA and lgtC within the lgtABCDE operon of Neisseria gonorrhoeae can modulate gonococcal susceptibility to normal human serum. J Endotoxin Res. 2002;8:47–58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shafer WM, Martin LE, Spitznagel JK. Late Intraphagosomal Hydrogen Ion Concentration Favors the In Vitro Antimicrobial Capacity of a 37-Kilodalton Cationic Granule Protein of Human Neutrophil Granulocytes. 1986a;53:651–655. doi: 10.1128/iai.53.3.651-655.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shafer WM, Onunka VC, Hitchcock PJ. A Spontaneous Mutant of Neisseria gonorrhoeae with Decreased Resistance to Neutrophil Granule Proteins. J Infect Dis. 1986b;153:910–917. doi: 10.1093/infdis/153.5.910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shafer WM, Onunka VC, Martin LE. Antigonococcal activity of human neutrophil cathepsin G. Infect Immun. 1986c;54:184–8. doi: 10.1128/iai.54.1.184-188.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shafer WM, Shepherd ME, Boltin B, Wells L, Pohl J. Synthetic peptides of human lysosomal cathepsin G with potent antipseudomonal activity. Infect Immun. 1993;61:1900–8. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.5.1900-1908.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shell DM, Chiles L, Judd RC, Samar S, Rest RF. The Neisseria Lipooligosaccharide-Specific alpha -2 ,3-Sialyltransferase Is a Surface-Exposed Outer Membrane Protein. Infect Immun. 2002;70(7):3744–51. doi: 10.1128/IAI.70.7.3744-3751.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sørensen OE, Follin P, Johnsen a H., Calafat J, Tjabringa GS, Hiemstra PS, Borregaard N. Human cathelicidin, hCAP-18, is processed to the antimicrobial peptide LL-37 by extracellular cleavage with proteinase 3. Blood. 2001;97:3951–9. doi: 10.1182/blood.v97.12.3951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinstraesser L, Kraneburg U, Jacobsen F, Al-Benna S. Host defense peptides and their antimicrobial-immunomodulatory duality. Immunobiology. 2011;216:322–33. doi: 10.1016/j.imbio.2010.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stohl EA, Criss AK, Seifert HS. The transcriptome response of Neisseria gonorrhoeae to hydrogen peroxide reveals genes with previously uncharacterized roles in oxidative damage protection. Mol Microbiol. 2005;58:520–32. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2005.04839.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stohl EA, Seifert HS. The recX gene potentiates homologous recombination in Neisseria gonorrhoeae. Mol Microbiol. 2001;40:1301–10. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2001.02463.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tzeng Y, Ambrose KD, Zughaier S, Zhou X, Miller YK, Shafer WM, et al. Cationic Antimicrobial Peptide Resistance in Neisseria meningitidis. J Bacteriol. 2005;187(5):5387–96. doi: 10.1128/JB.187.15.5387-5396.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization . Emergence of multi-drug resistant Neisseria gonorrhoeae – Threat of global rise in untreatable sexually transmitted infections. Geneva, Switzerland: 2011. [WWW document]. http://whqlibdoc.who.int/hq/2011/WHO_RHR_11.14_eng.pdf?ua=1. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization . Global Action Plan to control the spread and impact of antimicrobial resistance in Neisseria gonorrhoeae. Geneva, Switzerland: 2012. [WWW document]. http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2012/9789241503501_eng.pdf?ua=1. [Google Scholar]

- Juneau RA, Stevens JS, Apicella MA, Criss AK. A thermonuclease of Neisseria gonorrhoeae enhances bacterial escape from killing by neutrophil extracellular traps. J Infect Dis. 2015 Jan 20; doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiv031. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiv031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Figure Legends

Figure S1. Survival of parent, lptA mutant, and lptA complemented Gc induced with increasing concentrations of IPTG after exposure to polymyxin B. Parent, ΔlptA, and lptA+ complement were grown in the presence of IPTG at the indicated concentrations for 2.5 h, then exposed to 2μg ml−1 polymyxin B. Survival of Gc after 45 min is expressed as a percent of bacterial CFU at 0 min. *, P<0.05; Student’s two-tailed t-test, n=3 biological replicates per strain.

Figure S2. Growth is not attenuated in lptA mutant Gc. Broth-grown parent, ΔlptA, and lptA+ Gc were diluted to an OD550 of 0.07 and incubated over 4 h with shaking. Growth was assessed every hour by A) enumeration of CFU and B) optical density (550nm). n=4 biological replicates per strain.