Abstract

Background

Cystic lymphangioma is a rare benign lesion derived from the detachment of the lymph sacs from venous drainage systems; the treatment of choice is a surgical excision and the final diagnosis is of histological type.

Purpose

To compare the results of ultrasound (US), computed tomography (CT), and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) in patients with cystic lymphangioma to clearly evaluate the anatomic as well as the structural lesion features necessary for differential diagnosis and for the patient treatment planning.

Material and Methods

We analyzed the imaging results of six patients admitted in our department to evaluate cyst-like tumor masses clinically palpable or detected by US. All the patients underwent US, CT, and MRI. The pathology reports demonstrated a mesenterial cystic lymphangioma in five cases underwent surgical resection and in the last case a chest cystic lymphangioma underwent a fine needle aspiration biopsy (FNAB).

Results

In all the cases, the results of US, CT, and MRI were concordant showing cyst-like tumor masses in the abdomen (n = 5) and chest (n = 1) ranging in size from 3.5 to 15 cm.

Conclusion

According to our experience, we suggest that the appropriate diagnostic imaging protocol in patients with cystic lymphangioma should initially include the US study and followed by a MRI scan with contrast administration. CT should be avoided because of radiation exposure. US and MRI may also be useful in the follow-up of patients who refuse surgical resection or in whom surgery is contraindicated or postponed as well as to early detect a possible disease relapse.

Keywords: Imaging, cystic lymphangioma, abdomen, chest, ultrasound (US), computed tomography (CT), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)

Introduction

Cystic lymphangiomas are rare malformations characterized by cystic structure deriving from detachment of the lymph sacs from venous drainage system. They are preferentially localized in the neck and axillary region while mediastinal and abdominal, both mesenterial and retroperitoneal, locations are very rare approaching 5% of cases (1). The cystic variant of lymphangioma is included in the general classification of lymphangiomas according to Landing and Farber enclosing the capillary and venous variant. These ones are characterized respectively by the dilatation of capillary and sinusoidal lymphatic vessels which remain connected to the lymphatic network (2,3). Patients with cystic lymphangioma are often asymptomatic, but the lesion growth may show different symptoms depending on the lesion location and the size such as cough, respiratory disorders, dysphagia, vascular compression syndromes in case of thoracic mass (4) and abdominal pain or intestinal obstruction in case of abdominal location (5,6). Thus, the lesion detection and its characterization are clinically fundamental for the patient management. For this purpose, several diagnostic imaging modalities have been proposed showing a main role of ultrasound (US), computed tomography (CT), and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and also to guide the bioptic procedure for a cytological evaluation (3,7,8).

The aim of this study was the evaluation of comparative imaging results of US, CT, and MRI in patients with cystic lymphangioma to clearly assess the anatomic as well as the structural lesion which are necessary features for the patient’s treatment management and planning.

Material and Methods

Patient population

We have analyzed the imaging results of six patients (3 women, 3 men; age range, 18–67 years) admitted to our department to evaluate cyst-like tumor masses clinically palpable and/or detected by US. Patients had different symptoms depending on the size and the location of the tumor lesions. The main complaints consisted of abdominal pain in five cases of abdominal lesions and dysphagia with dyspnea in the case of mediastinal localization. All the patients underwent US, CT, and MRI. Patients with abdominal lesions underwent surgical resection while the patient with a mediastinal lesion underwent a fine needle aspiration biopsy (FNAB). The histology report showed mesenterial cystic lymphangiomas in abdominal lesions (sub-hepatic space = 2, hepatic hilum = 1, right iliac fossa = 1, and peritoneal space = 1), while FNAB showed a cystic epi-aortic lymphangioma in the mediastinum.

Imaging studies

The US study was performed with a Philips iU22 ultrasound instrument (Bothell, WA, USA) using a 7.5–13 MHz linear probe for the evaluation of neck lesion and a 3.5–5 MHz convex probe for the evaluation of abdominal lesions, integrated in both cases with color Doppler analysis.

The CT scan was performed with multi-detector computed tomography (MDCT) using a 64-row scanner (Aquilion 4, Toshiba, Japan) with a detector configuration of 3 mm × 4 mm, table feed of 9 mm/s, rotation time 0.5 s, beam pitch 1.5, 1.5 mm reconstruction intervals, section thickness of 3 mm, 300 mAs, 120 kVp; a monophasic acquisition was performed 70 s after i.v. bolus (2 cc/s) injection of 150 cc of iodinated non-ionic contrast media (Ultravist 370, Bayer Schering Pharma, Berlin, Germany): coronal reformatted images with multiplanar reconstruction (MPR) were obtained.

The MRI was performed using a superconductive 1.5 T magnete (Gyroscan Intera, Philips Medical Systems, Best, The Netherlands); the following sequences were used: axial T1-TSE (TR/TE, 217.8/4.6); axial and coronal T2-TSE-SSh (TR/TE, 831/80 ms); axial, coronal, and sagittal TRUFI single shot (TR/TE, 364/1.3 ms); subsequently, dynamic post-contrast (0.1 mmol/kg Gd-BOPTA Multihance, Bracco, Milan, Italy) T1-FFE sequence with pre-set scan times and image acquisition in the arterial (30 s), portal (60 s), equilibrium (180 s), and late phases (300 s) was performed. Axial and coronal planes were selected using a slice thickness of 3–5 mm.

Results

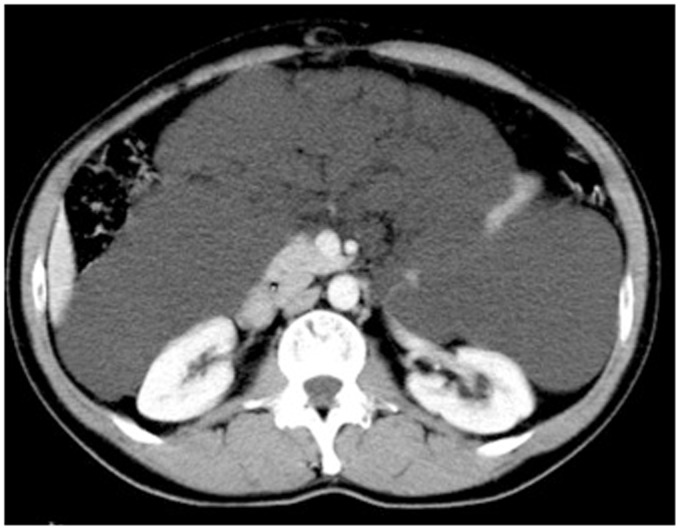

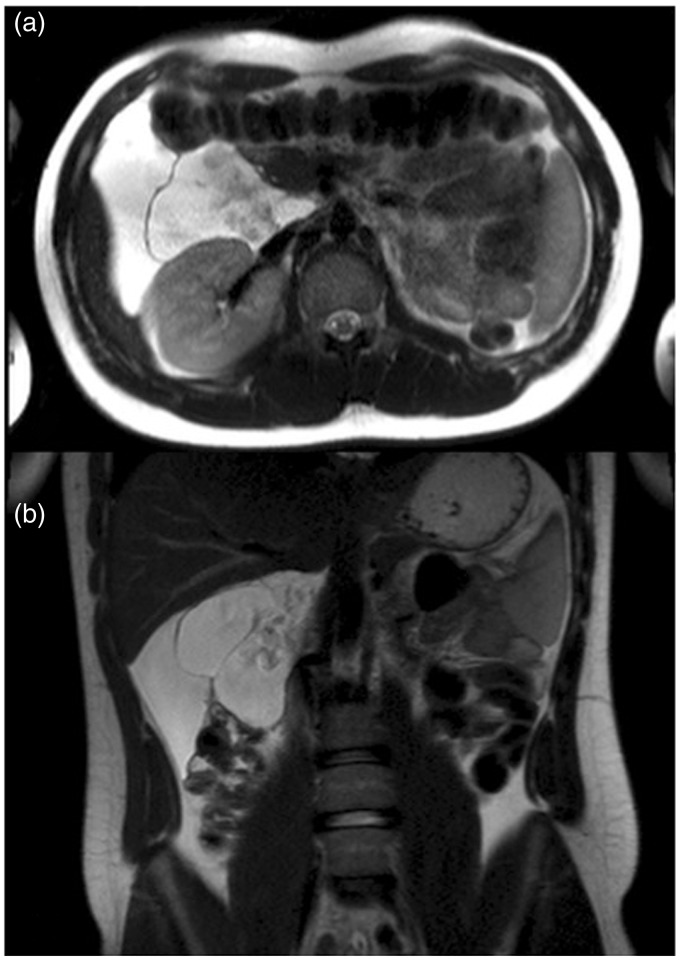

In all patients US, CT, and MRI findings were concordant and consisted of cyst-like tumor masses with different sizes in the range of 3.5–15 cm localized in different anatomic sites: mesenteric region (n = 5) and mediastinum (n = 1). On US images all the lesions were anechoic with regular margins; in five cases fine internal septimentations were detected, while the remaining lesion had homogeneous internal structure; color Doppler study revealed the presence of an only peripheral and weak vascular flow. On CT images lesions also appeared as cystic masses with homogeneous internal density approaching 15 HU and no contrast enhancement after intravenous injection (Fig. 1). MR sequences without intravenous contrast administration showed all masses as hyperintense on T2-weighted (T2W) sequences, suggesting fluid content, with regular margins, thin walls, and internal septa (Figs. 2–4); after gadolinium administration, only the walls and the internal septa showed an increased signal intensity on T1-weighted (T1W) sequence without internal contrast enhancement. Because of the higher contrast resolution of MRI compared to CT, a better evaluation of the internal lesion content, lesion wall thickness, and loco-regional tumor spread were obtained using MRI compared to CT.

Fig. 1.

Enhanced abdominal CT axial image shows a huge cystic mass composed by multiple confluent cystic lesions occupying the peritoneal spaces and displacing inferiorly the small bowel.

Fig. 2.

MRI of the abdomen. Axial (a) and coronal (b) T2W TSE images showed the presence of a huge fluid-filled mass with internal septa located in the hepato-renal space extending from the hepatic hilum to the right colon and displacing medially the second duodenal segment and anteriorly the hepatic flexure of the colon.

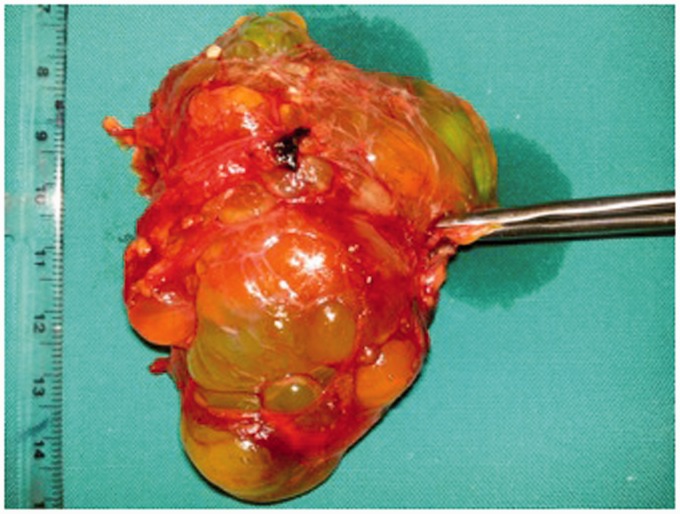

Fig. 3.

Cystic lymphangioma with polycyclic edge and internal septa (intraoperative specimen).

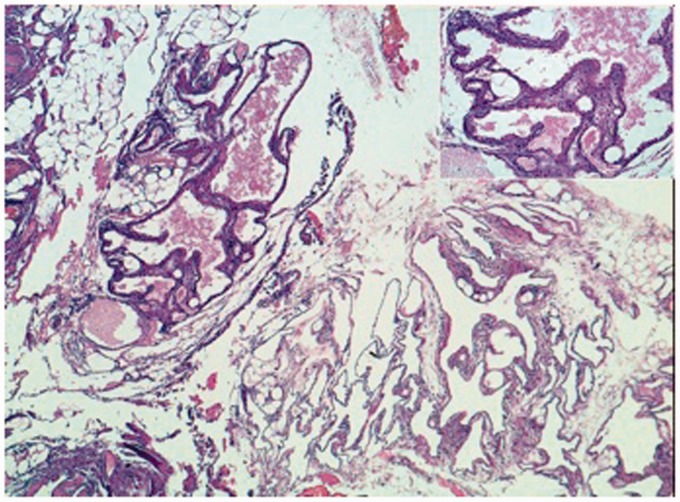

Fig. 4.

Numerous dilated lymphatic spaces, sometimes filled with lymph (EE 5X). Inset: focally lymphatic spaces are covered by plump endothelial cells (EE 20X).

Discussion

The cystic lymphangioma or cystic hygroma is a low-flow vascular malformation, developing where the lymph sacs are separated from the venous drainage system. The most common anatomic location is the neck region (75%), but it can also be found in the axillary region (20%) and less frequently in the mediastinum, retroperitoneum, mesentery, omentum, colon, pelvis, groin, bone, skin, scrotum, and spleen. Less than 1% of lymphangiomas are localized intra-abdominally and they mostly occur in the mesentery followed by the omentum, the mesocolon, and the retroperitoneum (9,10).

Imaging has a main role in the detection and characterization of cystic content either with US, CT, and/or MRI, as reported in our series. In all cases of our series US has been the technique of first choice in order to identify the lesion and to define its structural cystic-type characteristics as well as the tumor size. The diagnostic protocol was completed performing a CT and MRI; both imaging techniques provided accurate images clearly illustrating loco-regional lesion spread. On CT tumor masses showed densitometric characteristics of the fluid type, regular margins, and only a peripheral contrast enhancement. Although less available than CT, MRI allowed a clear evaluation of the lesion morphology and structure, better showing vessel-like internal septa, wall thickness, and fluid content, excluding the presence of mucoid, adipose, or solid components.

As previously suggested, MRI provides a better preoperative differentiation from other cyst-like masses (11,12); for example, bronchogenic cyst on T1W MRI may show a heterogeneous pattern since the presence of different components (protein, hemorrhage, mucoid material) with a fluid-fluid level on T2W sequences. Futhermore, there are other cystic lesions such as cystic teratoma and epydermoid cyst, that contain a certain amount of fat that can be easily detected with MRI (13). However, cystic lymphangioma may be indistinguishable from cystic benign mesothelioma on MRI because of similar fluid content even if the latter lesion is usually located on the surfaces of the pelvic viscera (14). US is considered as being the first level study to investigate a suspected mass suggestive of cystic lymphangioma because of its non-invasiveness, low cost, and non-use of ionizing radiation. However, this technique needs to be integrated with CT and MRI scans because of its non-panoramic view and also for obtaining additional information such as structural feature, internal and peripheral contrast enhancement, as well as loco-regional lesion spread. The value of imaging in cystic lymphangiomas is to exclude malignancy and to offer the exact anatomic location of the tumor before surgery. CT is currently performed with a multi-slice technique that allows a volumetric acquisition of the selected anatomic region with multi-planar reconstruction using different methods (MPR, MIP, SSD, VR). Furthermore, MRI is helpful in the surgical planning for its multiplanarity and high contrast resolution accurately showing loco-regional lesion spread.

However, some technical imaging limitations of our study need to be considered. First, a monophasic CT imaging acquisition after contrast injection was performed, while a multiphasic protocol should be more appropriate; second, only axial and coronal reconstructed CT images were used for the analysis in our study, while a complete imaging reconstruction in all three planes should be more appropriate to optimize CT imaging quality.

In conclusion, we suggest that an appropriate diagnostic imaging protocol in patients with cystic lymphangioma should initially include an US study with a successive MRI scan with contrast agent administration to further investigate lesion features in order to confirm or to rule out malignancy. US and MRI may also be useful in the follow-up of patients who refuse surgical resection or in whom surgery is contraindicated or postponed as well as to early detect a possible disease relapse.

Acknowledgements

Paper presented as EPOS (DOI: 10.1594/ecr2014/C-1023) during the European Congress of Radiology (ECR), Vienna, 6-10 March 2014.

Conflict of interest

None declared.

References

- 1.Viveiros Correia FMA, Seabra B, Rego A, et al. Cystic lymphangioma of the mediastinum. J Bras Pneumol 2008; 34: 994–996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Khobta N, Tomasini P, Trousse D, et al. Solitary cystic mediastinal lymphangioma. Eur Respir Rev 2013; 22: 91–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shaffer K, Rosado-de-Christenson ML, Patz EF, et al. Thoracic lymphangioma in adults: CT and MR imaging features. Am J Roetgenol 1994; 162: 283–289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Moore TC, Cobo JC. Massive symptomatic cystic hygroma confined to the thorax in early childhood. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 1985; 89: 459–462. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fundarò S, Medici L, Perrone S, et al. Cystic lymphangioma of the mesentery. A case of intestinal obstruction and a brief review of the literature. Minerva Chir 1998; 53: 939–942. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jang JH, Lee SL, Ku YM, et al. Small bowel volvulus induced by mesenteric lymphangioma in an adult: a case report. Korean J Radiol 2009; 10: 319–322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Davidson AJ, Hartman DS. Lymphangioma of the retroperitoneum. CT and sonographic characteristics. Radiology 1990; 175: 507–510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sarno RC, Carter BL, Bankoff MS. Cystic lymphangiomas: CT diagnosis and thin needle aspiration. Br J Radiol 1984; 57: 424–426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mohammadi A, Ghasemi-Rad M, Abassi F. Asymptomatic lymphangioma involving the spleen and mediastinum in adults. Med Ultrason 2013; 15: 154–156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Levy AD, Cantisani V, Miettinen M. Abdominal lymphangiomas: imaging features with pathologic correlation. Am J Roentgenol 2004; 182: 1485–1491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jeung MY, Gasser B, Gangi A, et al. Imaging of cystic masses of the mediastinum. Radiographics 2002; 22: S79–S93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yang DM, Fung DH, Kim H, et al. Retroperitoneal cystic masses: CT, clinical, and pathologic findings and literature review. Radiographics 2004; 24: 1353–1365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yoo E, Kim MJ, Kim KW, et al. A case of mesenteric cystic lymphangioma: fat saturation and chemical shift MR imaging. J Magn Reson Imaging 2006; 23: 77–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.O’Neil JO, Ros PR, Storm B.L, et al. Cystic mesothelioma of the peritoneum. Radiology 1989; 170: 333–337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]