Abstract

Infliximab (IFX) is an anti-tumor necrosis factor chimeric antibody that is effective for treatment of autoimmune disorders such as Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis (UC). IFX is well tolerated with a low incidence of adverse effects such as infections, skin reactions, autoimmunity, and malignancy. Dermatological manifestations can appear as infusion reaction, vasculitis, cutaneous infections, psoriasis, eczema, and skin cancer. Here, we present an unusual case of extensive and sporadic subcutaneous ecchymosis in a 69-year-old woman with severe UC, partial colectomy and cecostomy, following her initial dose of IFX. The reaction occurred during infliximab infusion, and withdrawal of IFX led to gradual alleviation of her symptoms. We concluded that Henoch-Schönlein purpura, a kind of leukocytoclastic vasculitis, might have contributed to the development of the bruising. Although the precise mechanisms of the vasculitis are still controversial, such a case highlights the importance of subcutaneous adverse effects in the management of UC with IFX.

Keywords: Henoch-Schönlein purpura, Infliximab, Vasculitis, Subcutaneous ecchymosis, Ulcerative colitis

Core tip: Infliximab (IFX) is effective in the management of ulcerative colitis (UC). Henoch-Schönlein purpura (HSP) appears as a dermatological adverse effect of IFX. However, extensive ecchymosis in old UC patients is rare. This report describes a case of HSP reaction, which resolved upon IFX withdrawal.

INTRODUCTION

Ulcerative colitis (UC) is a chronic autoimmune disorder of the colonic mucosa, which generally affects the rectum and may extend proximally to other parts of the colon, with continuous alternating relapse and remission. The crude annual incidence of UC per 100000 is up to 2.22 and has increased rapidly in recent years[1]. Traditional therapies include aminosalicylates, corticosteroids, and immunosuppressive medications such as azathioprine and 6-mercaptopurine. Approximately 9.8% of patients required colectomy under conventional medication[2]. Infliximab (IFX), a monoclonal antibody against tumor necrosis factor (TNF), is effective in UC patients[3-5]. Clinical remission of refractory UC patients under IFX treatment was 53% and 47% at 6 and 12 mo, respectively[6]. For long-term efficacy, 46% of patients achieved sustained clinical response at median follow-up of 41.5 mo[7]. The cumulative incidence of colectomy was 10% for IFX, while 17% of patients under placebo treatment needed colectomy after 54 wk[8]. Therefore, IFX is an effective medication to avoid colectomy and sustain long-term remission from refractory UC. However, significant, but rare, sometimes fatal drug-induced adverse effects have been reported in association with IFX, including infections, skin reactions, immunogenicity, malignancy, neurological complications, hepatotoxicity, congestive heart failure and hematological side effects[9].

Cutaneous complications can appear as infusion and injection site reactions, papulopustular eruptions, vasculitis, cutaneous infections and malignant neoplasms, and autoimmune skin disorders[10-12]. Henoch-Schönlein purpura (HSP), an acute vasculitic syndrome, is a rare side effect of anti-TNF medication and it is a complication associated with several anti-TNF agents, such as etanercept for psoriasis and rheumatoid arthritis[13,14], adalimumab for Crohn’s disease[15,16], and IFX for herpes zoster infection in UC[17]. HSP is more prevalent in children, while no study has described the development of severe HSP in elderly patients, which is rare in clinical situations. Here, we present an unusual case of IFX-induced subcutaneous ecchymosis during intravenous treatment in a 69-year-old woman with severe UC, partial colectomy and cecostomy.

CASE REPORT

A 69-year-old woman, previously diagnosed with UC, with partial colectomy and cecostomy, was admitted to the Department of Gastroenterology of Shanghai 10th People’s Hospital, China, complaining of lower abdominal pain and hematochezia for 8 mo.

In September 2008, she was admitted to a local hospital for the first time with frequent hematochezia and abdominal pain. Colonoscopy at that time showed multiple ulcers in the ascending colon. A specimen biopsy of inflammatory regions revealed mucosal congestion, infiltration of massive lymphocytes, plasmocytes and neutrophils in the hepatic and splenic flexure of the transverse colon. Polypoid hyperplasia was also seen in part of the colon. Thus, she was diagnosed with UC and received mesalamine (Salofalk; Dr. Falk Pharma GmbH, Germany) at a dose of 1.0 g three times daily for 4 years until now, but her symptoms of hematochezia and abdominal pain were not alleviated completely.

In August 2012, the patient did not respond well to previous medication and still had persistent abdominal pain and hematochezia. Therefore, she received partial colectomy at the local hospital, including surgical removal of the transverse colon, and partial removal of the ascending and descending colon. Cecostomy was also performed. Five months later, ileostomy was performed with surgical removal of the terminal ileum. Eight months later, she complained of abdominal pain and frequent hematochezia about twice daily. Colonoscopy revealed mucosal congestion and edema, as well as multiple ulcerations. Thus, she received enemas of mesalamine (4.0 g qd; Salofalk), diosmectite (6.0 g qd; Smecta; Beaufour-Ipsen Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd., Tianjin, China) and ethamsylate (0.5 g qd; Tianjin Jinyao Amino Acid Co. Ltd., Tianjin, China) but hematochezia persisted.

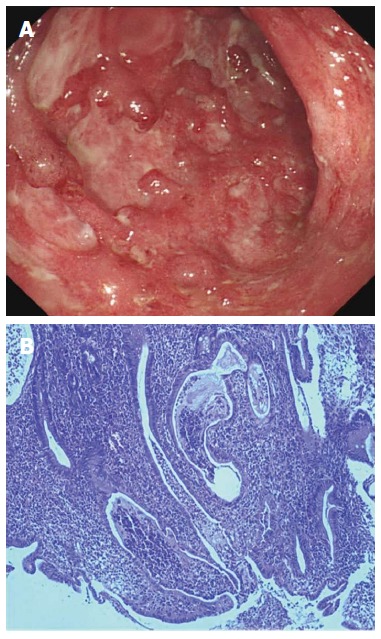

The patient was admitted to the Department of Gastroenterology in Shanghai 10th People’s Hospital on July 30, 2013 for further treatment. She still had hematochezia, about twice daily. Her medical history included partial colectomy and cecostomy as described previously. She denied a history of bleeding or coagulation disorders, high blood pressure, or diabetes. Family history revealed nothing for both her parents and children. Allergic history was negative for any specific medication or food. She was married and gave birth to a daughter and a son at the age of 23 and 25 years, respectively. Routine blood tests showed a leukocyte count of 6.10 × 109/L (normal range: 3.5 × 109-9.5 × 109/L), with 72.5% neutrophils (normal range: 40%-75%), 18.5% lymphocytes (normal range: 20%-50%) and 7.5% monocytes (normal range: 3%-10%). Hemocytological analysis showed a hemoglobin level of 99 g/L (normal range: 130-175 g/L), erythrocyte count of 3.25 × 1012/L (normal range: 4.3 × 1012-5.8 × 1012/L), platelet count of 291 × 109/L (normal range: 100 × 109-300 × 109/L), and erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) of 45 mm/h (normal range: 0-15 mm/h). The level of C-reactive protein (CRP) was 3.3 mg/L (normal range: 0-8.2 mg/L). Coagulation parameters were within normal ranges. All autoimmune antibodies, including antinuclear antibody, anti-smooth muscle antibody, anti-SSA antibody, anti-SSB antibody, perinuclear antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody, anti-Scl-70 antibody, anti-Jo-1 antibody, anti-PM-Scl antibody, anti-double-stranded DNA antibody, anti-nucleosome antibody, anti-histone antibody, and anti-mitochondrial M2 antibody, were negative at the time of examination. Renal and liver function tests were unremarkable. Stool microbial cultures including bacteria [Clostridium difficile (C. difficile), Salmonella, Staphylococcus aureus (S. aureus) and Escherichia coli (E. coli)] and viruses (cytomegalovirus and human immunodeficiency virus) were also negative. Bacterial toxins from C. difficile, E. coli O157, Salmonella and S. aureus, as well as lipopolysaccharide and peptidoglycan in serum were undetectable. T-SPOT.TB test for Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection was negative. Computed tomography enterography indicated inhomogeneous colonic mural thickening enhancement and stratification. Colonoscopy demonstrated severe inflammation in the intestinal lumen 50 cm from the anus, mucosal congestion and edema, and multiple hemorrhage and ulceration, with purulent adhesions (Figure 1A). Histological biopsy revealed extensive infiltration of immune cells, cryptitis, and glandular distortion in the intestine (Figure 1B). Thus, diagnosis of UC was confirmed.

Figure 1.

Colonoscopy and histological finding in a ulcerative colitis patient. A: Colonoscopy demonstrated severe mucosal congestion and edema, multiple hemorrhage and ulcerations in the descending colon; B: Histological section revealed extensive infiltration of immune cells, cryptitis and glandular distortion in the inflamed colon.

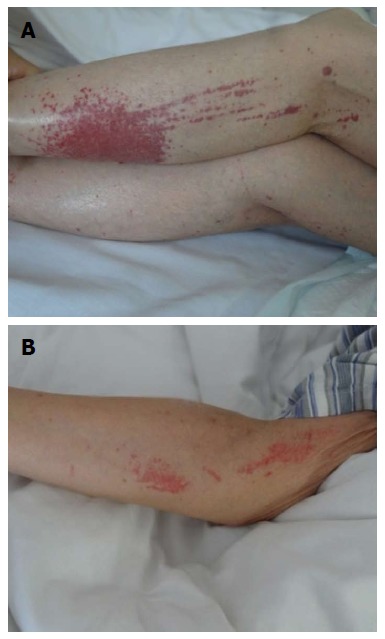

She received mesalamine enema (4.0 g qd) and started intravenous IFX (200 mg; Cilag AG, Schaffhausen, Switzerland) for improvement of her symptoms. During IFX infusion, the patient had extensive subcutaneous ecchymosis on her left lower extremity, with diameters of 4 cm (Figure 2A). Sporadic bruising was also present on her upper extremities, with diameters of 1 cm (Figure 2B). All ecchymoses were painless and faded under pressure. Physical examination showed a small amount of purulent fluids around the fistula and drainage was unobstructed. There was slight tenderness in the abdomen, with no rebound pain. IFX was discontinued on the suspicion that it might have been responsible for the bruising. Emergency laboratory analyses revealed a leukocyte count of 4.06 × 109/L (normal range: 3.5 × 109-9.5 × 109/L), with 80.5% neutrophils (normal range: 40%-75%), 11.1% lymphocytes (normal range: 20%-50%) and 7.8% monocytes (normal range: 3%-10%). Hemocytological analysis demonstrated a platelet count of 249 × 109/L (normal range: 100 × 109-300 × 109/L), and hemoglobin of 99 g/L (normal range: 130-175 g/L). CRP was 20.3 mg/L (normal range: 0-8.2 mg/L), and D-dimer was 3.11 mg/L (normal range: 0-0.55 mg/L). Electrolytes results indicated 2.9 mmol/L potassium (normal range: 3.5-5.1 mmol/L), 135 mmol/L sodium (normal range: 136-145 mmol/L), 2.04 mmol/L sodium (normal range: 2.10-2.55 mmol/L), and 0.66 mmol/L magnesium (normal range: 0.7-1.0 mmol/L). Urinalysis showed proteinuria and microscopic hematuria. Coagulation index demonstrated prothrombin time of 11 s (normal range: 9.5-14.5 s), activated partial thromboplastin time of 28.4 s (normal range: 23-36 s), international normalized ratio of 0.92 (normal range: 1.1-1.6), thrombin time of 20.6 s (normal range: 12-18 s), and fibrinogen of 3.10 g/L (normal range: 1.8-3.5 g/L). Liver function tests and serum amylase were unremarkable. She had not taken other drugs, over-the-counter medications, or herbal products. She was just undergoing UC diet therapy and denied a history of recent trauma. Upon a suggestion from the hematologist and dermatologist, she was prescribed with vitamin C tablets (0.1 g qd; Beijing Double-Crane Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd.), carbazochrome tablets (2.5 mg tid; Yabang Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd., Jiangsu, China), compound glycyrrhizin tablets (0.5 g tid; Minophagen Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd., Japan) and calamine lotion (twice daily; Shanghai Winguide Huangpu Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd. China) for treatment of the bruising. Such bruising did not vanish until 7 d later after discontinuation of IFX.

Figure 2.

Subcutaneous ecchymosis on the left upper and lower extremities. A: Extensive bruising on the left lower extremity; B: Sporadic purpura on the left upper extremity.

On August 23, 2013, the patient was admitted again for hematochezia and planned to continue a second round of IFX administration. About 40 min after infusion of 200 mg IFX, the patient complained of pruritus all over her body and sporadic erythema could be seen, especially distributed on her extremities. Dyspnea, abdominal pain, nausea or other remarkable symptoms were not observed. Physical examination showed blood pressure (106/70 mmHg), heart rates (70 beats/min), respiratory rate (14/min) were within the normal ranges. Emergency laboratory results, including liver and renal function tests, bleeding time and blood-clotting tests, and electrolytes were all normal. ESR was 37 mm/h (normal range: 0-15 mm/h). Urinalysis showed proteinuria and microscopic hematuria. IFX infusion was immediately discontinued temporarily. She was prescribed with promethazine (25 mg; Phenergan; Shanghai Harvest Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd., China) intramuscularly and 10% calcium gluconate (10 mL; Tianjin Jinyao Amino Acid Co. Ltd.) intravenously for further treatment of her skin reactions. Her symptoms alleviated partially and spontaneously 7 d later.

DISCUSSION

Anti-TNF agents have revolutionized the therapy of several immune-mediated diseases, including corticosteroid-dependent fistulizing Crohn’s disease and refractory UC. However, adverse effects may occur during IFX management. They include infections, dermatological reactions, immunogenicity, neurological complications, malignancy, hepatotoxicity, congestive heart failure and hematological side effects. In some cases, these reactions may cause drug discontinuation, thus making it harder to treat UC[9,15]. Thus, adverse effects of anti-TNF agents can’t be neglected in clinical situations.

One of the dermatological manifestations is HSP, which is an acute leukocytoclastic vasculitis characterized by IgA immune complexes in small vessels, with extensive or sporadic purpura especially on the lower extremities and buttocks as a characteristic clinical manifestation. The incidence of vasculitis during administration of TNF antagonists ranges from 0.02% to 3.9%[18,19]. It is reported more frequently in children than adults. HSP has been described as a significant adverse effect with commonly used anti-TNF medications, including etanercept[13,14], adalimumab[15,16], and IFX[17]. Aside from skin features, renal dysfunction such as crescentic glomerulonephritis can be involved[20]. In some serious cases, gastrointestinal impairment, such as intestinal bleeding and perforation, as well as peripheral nervous system injury has been reported[21,22]. Usually, serum anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies are undetectable before the initiation of anti-TNF medication, but are positive in some patients during vasculitis. The prognosis is more severe in adults with more complications than children.

Michel et al[23] identified six diagnostic criteria for HSP, including palpable purpura not related to thrombocytopenia, bowel angina, gastrointestinal bleeding, hematuria, age < 20 years, and no history of medication at the onset of disease. A patient is diagnosed with HSP if ≥ 3 criteria are met. The possible explanation for our case is the development of HSP. In our study, the patient was an old woman with a medical history of UC for 5 years. She was diagnosed with UC in 2008 and underwent partial colectomy and cecostomy in 2012, but her symptoms recurred 8 mo later. In July 2013, the patient was admitted to our department and started IFX administration, during which she developed extensive and sporadic ecchymosis. Urinalysis revealed hematochezia and microscopic hematuria. Although hematochezia could be a clinical characterization of UC, and it is doubtful whether hematochezia is caused by UC or IFX-induced HSP, mesalamine had been used before IFX to control her symptoms of UC. Besides, hematochezia deteriorated after IFX administration, further indicating that IFX might have contributed to the exacerbation. She complained of slight abdominal tenderness. No abnormalities were found in her platelet counts, bleeding time or coagulation function tests. All clinical hallmarks coincided with HSP. A specimen biopsy of bruising skin lesions was warranted for confirmation of the diagnosis. HSP is more prevalent in pediatric patients, and is rare in elderly patients, with complex medical histories and weak general condition, such as the present case. In previous studies, bruising was sporadically distributed on the extremities. In our case, ecchymosis was extensive which was rare in clinical situations. Such extensive ecchymosis indicated vasculitis could be more severe.

Although the precise mechanisms of purpural vasculitis are still controversial, current hypotheses focus on a type III hypersensitivity reaction triggered by release of anti-IFX autoimmune antibodies from capillaries, possible cytokine imbalance due to blockage of TNF and its regulation of CD23 on T-cell-activated B cells, and a shift from T helper (Th)1 to Th2 response[24-26].

In conclusion, in agreement with previous studies[15,27,28], our study highlights the importance of subcutaneous adverse manifestations during IFX management, especially those whose clinical symptoms are not typical enough to make an accurate diagnosis. Thus, prior to biological therapies with anti-TNF agents, certain risk analyses should be assessed and patients need to be carefully selected for optimal anti-TNF agents.

COMMENTS

Case characteristics

A 69-year-old female patient with ulcerative colitis (UC) developed severe Henoch-Schönlein purpura (HSP) during infliximab (IFX) administration.

Clinical diagnosis

Subcutaneous purpura on her extremities, severe hematochezia and slight tenderness in the abdomen were observed.

Differential diagnosis

Cutaneous infections, psoriasis, eczema, and other dermatological disorders.

Laboratory diagnosis

All laboratory results coincided with the diagnosis of UC and no abnormalities were found in her platelet counts, bleeding-time and coagulation function tests.

Imaging diagnosis

Computed tomography enterography indicated inhomogeneous colonic mural thickening enhancement and stratification.

Pathological diagnosis

Histological biopsy revealed extensive infiltration of immune cells, cryptitis, and glandular distortion in the intestine, while pathological examination of the ecchymosis was not performed.

Treatment

She was prescribed vitamin C tablets, carbazochrome tablets, compound glycyrrhizin tablets, and calamine lotion for treatment of the bruising.

Related reports

HSP has been described as a significant adverse effect with commonly used anti-tumor necrosis factor (TNF) agents, including etanercept, adalimumab, and IFX in young patients.

Term explanation

HSP is a type of vasculitis characterized by IgA immune complexes in the blood vessels and is regarded as a cutaneous side effect of anti-TNF agents such as IFX.

Experiences and lessons

The authors should take this adverse effect HSP into consideration during IFX administration for refractory UC.

Peer-review

This case report focused on HSP, which is a cutaneous complication during IFX treatment. In our case, a 69-years-old patient developed severe HSP, which is rare in clinical situations. Clinical points of diagnosis and treatment are addressed. A specimen biopsy of bruising skin lesions was warranted.

Footnotes

Supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China, No. 81270470.

Ethics approval: The study was reviewed and approved by the Hospital and University Review Committees for Medical Research.

Informed consent: All study participants, or their legal guardians, provided informed written consent prior to study enrollment.

Conflict-of-interest: The authors declared no conflict interests.

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article which was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Peer-review started: November 24, 2014

First decision: December 11, 2014

Article in press: February 11, 2015

P- Reviewer: Chen JX S- Editor: Ma YJ L- Editor: A E- Editor: Zhang DN

References

- 1.Ng SC, Tang W, Ching JY, Wong M, Chow CM, Hui AJ, Wong TC, Leung VK, Tsang SW, Yu HH, et al. Incidence and phenotype of inflammatory bowel disease based on results from the Asia-pacific Crohn’s and colitis epidemiology study. Gastroenterology. 2013;145:158–165.e2. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2013.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Solberg IC, Lygren I, Jahnsen J, Aadland E, Høie O, Cvancarova M, Bernklev T, Henriksen M, Sauar J, Vatn MH, et al. Clinical course during the first 10 years of ulcerative colitis: results from a population-based inception cohort (IBSEN Study) Scand J Gastroenterol. 2009;44:431–440. doi: 10.1080/00365520802600961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Reinisch W, Van Assche G, Befrits R, Connell W, D’Haens G, Ghosh S, Michetti P, Ochsenkühn T, Panaccione R, Schreiber S, et al. Recommendations for the treatment of ulcerative colitis with infliximab: a gastroenterology expert group consensus. J Crohns Colitis. 2012;6:248–258. doi: 10.1016/j.crohns.2011.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Monterubbianesi R, Aratari A, Armuzzi A, Daperno M, Biancone L, Cappello M, Annese V, Riegler G, Orlando A, Viscido A, et al. Infliximab three-dose induction regimen in severe corticosteroid-refractory ulcerative colitis: early and late outcome and predictors of colectomy. J Crohns Colitis. 2014;8:852–858. doi: 10.1016/j.crohns.2014.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Reinisch W, Sandborn WJ, Rutgeerts P, Feagan BG, Rachmilewitz D, Hanauer SB, Lichtenstein GR, de Villiers WJ, Blank M, Lang Y, et al. Long-term infliximab maintenance therapy for ulcerative colitis: the ACT-1 and -2 extension studies. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2012;18:201–211. doi: 10.1002/ibd.21697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Armuzzi A, Pugliese D, Danese S, Rizzo G, Felice C, Marzo M, Andrisani G, Fiorino G, Sociale O, Papa A, et al. Infliximab in steroid-dependent ulcerative colitis: effectiveness and predictors of clinical and endoscopic remission. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2013;19:1065–1072. doi: 10.1097/MIB.0b013e3182802909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Armuzzi A, Pugliese D, Danese S, Rizzo G, Felice C, Marzo M, Andrisani G, Fiorino G, Nardone OM, De Vitis I, et al. Long-term combination therapy with infliximab plus azathioprine predicts sustained steroid-free clinical benefit in steroid-dependent ulcerative colitis. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2014;20:1368–1374. doi: 10.1097/MIB.0000000000000115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sandborn WJ, Rutgeerts P, Feagan BG, Reinisch W, Olson A, Johanns J, Lu J, Horgan K, Rachmilewitz D, Hanauer SB, et al. Colectomy rate comparison after treatment of ulcerative colitis with placebo or infliximab. Gastroenterology. 2009;137:1250–1260; quiz 1520. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.06.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rosenblum H, Amital H. Anti-TNF therapy: safety aspects of taking the risk. Autoimmun Rev. 2011;10:563–568. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2011.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Moustou AE, Matekovits A, Dessinioti C, Antoniou C, Sfikakis PP, Stratigos AJ. Cutaneous side effects of anti-tumor necrosis factor biologic therapy: a clinical review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;61:486–504. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2008.10.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Moran GW, Lim AW, Bailey JL, Dubeau MF, Leung Y, Devlin SM, Novak K, Kaplan GG, Iacucci M, Seow C, et al. Review article: dermatological complications of immunosuppressive and anti-TNF therapy in inflammatory bowel disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2013;38:1002–1024. doi: 10.1111/apt.12491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mocci G, Marzo M, Papa A, Armuzzi A, Guidi L. Dermatological adverse reactions during anti-TNF treatments: focus on inflammatory bowel disease. J Crohns Colitis. 2013;7:769–779. doi: 10.1016/j.crohns.2013.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Duffy TN, Genta M, Moll S, Martin PY, Gabay C. Henoch Schönlein purpura following etanercept treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2006;24:S106. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee A, Kasama R, Evangelisto A, Elfenbein B, Falasca G. Henoch-Schönlein purpura after etanercept therapy for psoriasis. J Clin Rheumatol. 2006;12:249–251. doi: 10.1097/01.rhu.0000239901.34561.5e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Marques I, Lagos A, Reis J, Pinto A, Neves B. Reversible Henoch-Schönlein purpura complicating adalimumab therapy. J Crohns Colitis. 2012;6:796–799. doi: 10.1016/j.crohns.2012.02.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rahman FZ, Takhar GK, Roy O, Shepherd A, Bloom SL, McCartney SA. Henoch-Schönlein purpura complicating adalimumab therapy for Crohn’s disease. World J Gastrointest Pharmacol Ther. 2010;1:119–122. doi: 10.4292/wjgpt.v1.i5.119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nobile S, Catassi C, Felici L. Herpes zoster infection followed by Henoch-Schönlein purpura in a girl receiving infliximab for ulcerative colitis. J Clin Rheumatol. 2009;15:101. doi: 10.1097/RHU.0b013e31819bca9e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jarrett SJ, Cunnane G, Conaghan PG, Bingham SJ, Buch MH, Quinn MA, Emery P. Anti-tumor necrosis factor-alpha therapy-induced vasculitis: case series. J Rheumatol. 2003;30:2287–2291. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Flendrie M, Vissers WH, Creemers MC, de Jong EM, van de Kerkhof PC, van Riel PL. Dermatological conditions during TNF-alpha-blocking therapy in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a prospective study. Arthritis Res Ther. 2005;7:R666–R676. doi: 10.1186/ar1724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Davin JC. Henoch-Schonlein purpura nephritis: pathophysiology, treatment, and future strategy. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2011;6:679–689. doi: 10.2215/CJN.06710810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ramos-Casals M, Roberto-Perez-Alvarez C, Cuadrado MJ, Khamashta MA. Autoimmune diseases induced by biological agents: a double-edged sword? Autoimmun Rev. 2010;9:188–193. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2009.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhang Y, Huang X. Gastrointestinal involvement in Henoch-Schönlein purpura. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2008;43:1038–1043. doi: 10.1080/00365520802101861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Michel BA, Hunder GG, Bloch DA, Calabrese LH. Hypersensitivity vasculitis and Henoch-Schönlein purpura: a comparison between the 2 disorders. J Rheumatol. 1992;19:721–728. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.De Miguel S, Jover JA, Vadillo C, Judez E, Loza E, Fernandez-Gutierrez B. B cell activation in rheumatoid arthritis patients under infliximab treatment. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2003;21:726–732. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Guillevin L, Mouthon L. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha blockade and the risk of vasculitis. J Rheumatol. 2004;31:1885–1887. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mohan N, Edwards ET, Cupps TR, Slifman N, Lee JH, Siegel JN, Braun MM. Leukocytoclastic vasculitis associated with tumor necrosis factor-alpha blocking agents. J Rheumatol. 2004;31:1955–1958. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sokumbi O, Wetter DA, Makol A, Warrington KJ. Vasculitis associated with tumor necrosis factor-α inhibitors. Mayo Clin Proc. 2012;87:739–745. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2012.04.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mälkönen T, Wikström A, Heiskanen K, Merras-Salmio L, Mustonen H, Sipponen T, Kolho KL. Skin reactions during anti-TNFα therapy for pediatric inflammatory bowel disease: a 2-year prospective study. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2014;20:1309–1315. doi: 10.1097/MIB.0000000000000088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]