Abstract

Several previous studies found that Asians transplanted for hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection had worse post-transplant outcomes than Caucasians. Data on post-transplant outcomes of African Americans and waitlist outcomes of Asian Americans and African Americans with hepatitis B are scant. The aim of this study was to compare waitlist and post-transplant outcomes among Asian Americans, African Americans, and Caucasians who had HBV-related liver disease. Data from a retrospective-prospective study on liver transplantation for HBV infection were analyzed. A total of 274 patients (116 Caucasians, 135 Asians, and 23 African Americans) from 15 centers in the United States were enrolled. African Americans were younger and more Asian Americans had hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) at the time of liver transplant listing. The probability of undergoing transplantation and the probability of survival on the waitlist were comparable in the 3 racial groups. Of the 170 patients transplanted, 19 died during a median follow-up of 31 months. The probability of post-transplant survival at 5 years was 94% for African Americans, 85% for Asian Americans, and 89% for Caucasians (P = 0.93). HCC recurrence was the only predictor of post-transplant survival, and recurrence rates were similar in the 3 racial groups. Caucasians had a higher rate of HBV recurrence: 4-year recurrence was 19% versus 7% and 6% for Asian Americans and African Americans, respectively (P = 0.043). In conclusion, we found similar waitlist and post-transplant outcomes among Caucasians, Asian Americans, and African Americans with hepatitis B. Our finding of a higher rate of HBV recurrence among Caucasians needs to be validated in other studies.

Conflicting data exist as to whether race affects outcomes after orthotopic liver transplantation (OLT) in the United States. Results from 1 center found no significant difference in patient survival between African Americans and Caucasians after solid organ transplantation, including liver transplantation.1 In contrast, a retrospective analysis of the United Network of Organ Sharing (UNOS) database of over 14,000 OLT procedures performed between 1988 and 1996 revealed that 2- and 5-year patient survival was significantly lower for both African Americans and Asians compared to white Americans and Hispanics.2 This study found that the racial difference in post-OLT survival was related to the etiology of liver disease, with lower survival rates among African Americans with hepatitis C or acute liver failure and among Asians with hepatitis B virus (HBV). A second analysis of the UNOS database, which included more than 17,000 OLT procedures performed during the same period (1990-1996), also concluded that post-OLT survival was lower in minority races.3 However, a recent analysis of 2823 patients transplanted in 4 centers between 1985 and 2000 found no difference in post-OLT patient or graft survival among racial groups.4 In this study, a significantly increased risk of mortality was observed among patients of other races (not Caucasian or African American) transplanted before 1994, and this was attributed to the poor outcome of patients transplanted for hepatitis B or hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). These data indicate that racial differences in post-OLT outcome observed in some studies may be related to differences in the predominant cause of liver disease.

Several studies have compared outcomes of Caucasians and Asians transplanted for HBV infection. Three early studies found that Asians who had liver transplants for hepatitis B had higher rates of post-OLT mortality.5-7 Data from these single-center studies were confirmed by analysis of the large databases cited previously.2,4 Studies conducted after the introduction of hepatitis B immune globulin (HBIG) and lamivudine were more encouraging. A retrospective study of 70 Asians and 99 whites transplanted in the late 1990s found that post-OLT survival and HBV recurrence were comparable between the 2 groups.8 Similarly, an analysis of the UNOS database of all adult patients transplanted for HBV between 1997 and 2002 found that post-OLT survival of Asians was similar to that of other races.9 These data indicate that outcomes of Asians and Caucasians after liver transplantation for HBV infection in the recent era are comparable, but there are very little data on the outcomes of African Americans who had liver transplantation for hepatitis B. To date, most studies have focused on post-OLT outcomes; whether transplantation rates and outcomes on the waiting list are comparable among racial groups is unclear. Furthermore, most studies have not included data on HBV markers and HBV prophylactic regimen, factors that may affect post-OLT HBV recurrence and survival.

The National Institutes of Health (NIH)—sponsored HBV-OLT study is a multicenter retrospective-prospective study on the outcomes of liver transplant patients with HBV infection. The large number of enrolled patients permitted a comparison of post-OLT outcomes as well as outcomes on the waiting list among Caucasians, Asian Americans, and African Americans in an era in which oral nucleos/tide analogues and HBIG are available. This study also allowed a comparison of the clinical and virological characteristics of the patients in these racial groups.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Patient Population

The NIH HBV-OLT study is a retrospective-prospective observational study that enrolled hepatitis B surface antigen–positive patients who were 13 years of age or older from 15 centers in the United States.10 All patients either were on the liver transplant waiting list or were within 12 months post-transplant. Patients were listed between March 12, 1996 and June 10, 2005 and transplanted between March 28, 2001 and September 27, 2007. The study was approved by the institutional review board at each of the participating centers, and written informed consent was obtained from all patients prior to study entry. For patients enrolled at the time of listing, data were collected prospectively. For patients enrolled after placement on the liver transplant waiting list, data after enrollment were collected prospectively, while data prior to enrollment were collected retrospectively up to the time of listing.

For this analysis, patients with race/ethnicity other than Caucasian, Asian American, or African American, those coinfected with hepatitis C virus or human immunodeficiency virus, and those listed for retransplantation were excluded. Hispanics were not included as there were only 2 in this study. Demographic, clinical, laboratory [blood counts, creatinine, liver panel, prothrombin time/international normalized ratio, alpha-fetoprotein, hepatitis B serology, and HBV DNA], and radiological (for patients with HCC) data as well as start and stop dates of antiviral therapy and HBIG (for post-transplant patients) were entered into an electronic database. Data were collected at enrollment, transplant listing, and time of transplant and every 6 months on the transplant waiting list, every 3 months during the first year post-transplant, and every 6 months after the first post-transplant year. Race/ethnicity assignment was based on self-reporting by the patients. All laboratory tests except for HBV DNA and antiviral drug-resistant mutations were performed with commercially available assays at the participating centers. An additional 10 mL of blood was collected at each visit, centrifuged, divided into aliquots, and stored at −70°C at the participating centers and shipped in batches to the central laboratory at the University of Michigan, where serum samples were stored at −80°C until testing.

Because the NIH HBV-OLT study was an observational study, no specific treatment was tested, but the protocol did provide guidelines on the use of antiviral therapy pre-transplant and post-transplant and the use of HBIG post-transplant.

HBV DNA assays

Serum HBV DNA levels were quantified with the Cobas Amplicor HBV Monitor assay (Roche Molecular Systems, Inc., Branchburg, NJ) at the central laboratory. The lower limit of detection of this assay is 200 copies/mL. Samples with values > 100,000 copies/mL were diluted 1:1000- to 1:100,000-fold and retested. For patients with missing central laboratory samples, HBV DNA results at the participating centers were used, and the results were converted into log10 copies/mL with conversion formulae provided by the manufacturers.

HBV Antiviral Resistance Mutation Testing

Samples from patients with virological breakthrough during antiviral therapy prior to transplant were tested for antiviral resistance mutations by direct sequencing of the HBV polymerase gene (rt9-250) as well as a line probe assay (INNO-LiPA DRv2 and DRv3, Innogenetics, Ghent, Belgium).11,12

Statistical Analyses

Categorical data were presented as number and percentage and compared with the chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test as appropriate. Continuous variables were expressed as mean and standard deviation unless specified otherwise and compared with the t test or Mann-Whitney U test. The serum HBV DNA level was expressed as copies/mL and was logarithmically transformed.

An analysis of outcomes on the transplant waiting list, including deaths, dropouts (deaths or delisting due to disease progression), and time to transplant, and an analysis of outcomes post-transplant, including deaths, HBV recurrence, and HCC recurrence, were estimated with Kaplan-Meier analysis. Univariate analyses of factors associated with outcomes on the waiting list and outcomes post-transplant were performed with Kaplan-Meier analysis with the log rank test. Variables included in each analysis are shown in Table 1. Continuous variables were dichotomized, with the median taken as the cutoff value, except for serum HBV DNA, for which the cutoff used was 5 log10 copies/mL. Variables that had a P value of <0.2 on univariate analysis were entered into a Cox regression hazards model by forward logistic regression to determine the independent predictors of waitlist and post-OLT outcomes. All statistical analyses were performed with SPSS version 14.0.8 statistical software (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL).

TABLE 1.

Variables Included in the Analyses of Outcomes

| Probability of Transplantation |

Waitlist Mortality |

Post-OLT Survival |

HBV Recurrence |

HCC Recurrence |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | X | X | X | X | X |

| HBeAg status at listing | X | X | X | X | X |

| HBV DNA at listing | X | X | X | X | X |

| OLT indication at listing | X | X | X | X | X |

| Computed MELD score at listing | X | X | |||

| HCC staging at listing | X | X | |||

| New diagnoses of HCC on waiting list | X | X | X | ||

| OLT indication at transplant | X | X | |||

| HBeAg status at transplant | X | X | |||

| HBV DNA at transplant | X | X | |||

| Tumor stage at transplant | X | X | |||

| Use of antiviral therapy prior to OLT | X | X | |||

| Duration of antiviral therapy prior to OLT | X | X | |||

| Antiviral breakthrough prior to OLT | X | X | |||

| HBV recurrence post-OLT | X | ||||

| HCC recurrence post-OLT | X | ||||

| HBV prophylaxis post-OLT | X | X | |||

| Treatment for rejection | X | X | |||

| Duration of steroid use post-OLT | X | X | |||

| Transplant center | X | X | X | X | X |

Abbreviations: HBeAg, hepatitis B e antigen; HBV, hepatitis B virus; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; MELD, Model for End-Stage Liver Disease; OLT, orthotopic liver transplantation.

RESULTS

Characteristics of Patients at Transplant Listing

A total of 274 patients, including 116 Caucasians, 135 Asian Americans, and 23 African Americans, were included. Characteristics of the patients at transplant listing are summarized in Table 2. The vast majority of the patients were men: 82% of Caucasians, 76% of Asian Americans, and 74% of African Americans. African Americans were younger at the time of listing, but there was no difference in age between Asian Americans and Caucasians, with mean ages in the 3 groups being 45, 53, and 54 years, respectively (P < 0.001). Asian Americans were more likely to have HCC at listing than African Americans and Caucasians: 47% versus 17% and 16%, respectively (P < 0.001). Among the patients with HCC, a similarly high proportion in the 3 racial groups had tumors within the Milan criteria. Asian Americans were less likely to have acute liver failure as an indication for liver transplant and were less likely to be listed for end-stage cirrhosis than African Americans and Caucasians (P = 0.016 and P = 0.001). At listing, hepatitis B e antigen (HBeAg) status, HBV DNA levels, liver chemistries, and international normalized ratio were comparable among the 3 groups; however, Asian Americans had lower creatinine levels (P = 0.025), possibly because of the lower proportion of patients listed for acute liver failure or end-stage cirrhosis. Among the patients listed for end-stage cirrhosis, African Americans had higher Model for End-Stage Liver Disease (MELD) scores, but the difference was not significant. Similar percentages (52%-60%) of patients in the 3 groups were receiving antiviral therapy at listing.

TABLE 2.

Characteristics of Patients at Listing

| Characteristics of Patients at Listing |

P Values |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C | As | AA | All | C Versus As Versus AA |

C Versus As |

C Versus AA |

|

| No. of patients | 116 (42.3) | 135 (49.2) | 23 (8.3) | 274 (100) | |||

| Gender, male | 95 (81.9) | 103 (76.3) | 17 (73.9) | 215 (78.5) | NS | NS | NS |

| Age, years (mean ± SD) | 53.73 ± 8.92 | 52.76 ± 9.75 | 45.26 ± 14.20 | 52.54 ± 10.08 | 0.001 | NS | 0.001 |

| OLT indication | <0.001 | 0.001 | NS | ||||

| End-stage cirrhosis | 87 (75.0) | 67 (49.6) | 15 (65.2) | 169 (61.7) | 0.001 | <0.001 | NS |

| HCC | 19 (16.4) | 64 (47.4) | 4 (17.4) | 87 (31.8) | <0.001 | <0.001 | NS |

| Acute liver failure | 10 (8.6) | 4 (3.0) | 4 (17.4) | 18 (6.5) | 0.016 | 0.03 | NS |

| Labs at listing | |||||||

| HBeAg (+) | 39/105 (33.6) | 35/118 (25.9) | 6/18 (26.1) | 80/241 (29.2) | NS | NS | NS |

| HBV DNA detectable | 62/107 (57.9) | 70/117 (59.8) | 10/21 (47.6) | 142/245 (57.9) | NS | NS | NS |

| HBV DNA, log10 copies/mL (mean ± SD) | 4.1 ± 2.5 | 4.1 ± 2.2 | 3.9 ± 2.3 | 4.1 ± 2.4 | NS | NS | NS |

| HBV DNA > 5 log10 copies/mL | 38/107 (35.5) | 47/117 (40.2) | 6/21 (28.6) | 91/245 (37.1) | NS | NS | NS |

| ALT, U/L | 59 (6–2387) | 53 (3–8985) | 59 (22–1940) | 55 (3–8985) | NS | NS | NS |

| AST, U/L | 77 (15–1132) | 62 (8–7234) | 78.5 (18–1251) | 66 (8–7234) | NS | NS | NS |

| Bilirubin, mg/dL | 1.9 (0.4–41.5) | 1.5 (0.3–51.4) | 2.6 (0.4–28.7) | 1.8 (0.3–51.4) | NS | NS | NS |

| INR | 1.3 (0.9–7.3) | 1.3 (0.9–6.7) | 1.4 (1–3) | 1.3 (0.9–7.3) | NS | NS | NS |

| Creatinine, mg/dL | 1.0 (0.5–7.1) | 0.8 (0.4–6.4) | 1.0 (0.6–5.8) | 0.9 (0.4–7.1) | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.028 |

| End-stage cirrhosis: MELD | 13.0 (6–40) | 14.0 (6–40) | 15.5 (8–26) | 13.0 (6–40) | NS | NS | NS |

| HCC: within Milan criteria* | 13/19 (68.4) | 46/64 (71.8) | 4/4 (100) | 63/87 (72.4) | NS | NS | NS |

| Antiviral treatment at listing | 70 (60.3) | 78 (58.2) | 12 (52.2) | 160 (58.3) | NS | NS | NS |

NOTE: The results are expressed as number (%) or median (range) unless specified otherwise.

Abbreviations: ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AA, African Americans; As, Asian Americans; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; C, Caucasians; HBeAg, hepatitis B e antigen; HBV, hepatitis B virus; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; INR, international normalized ratio; MELD, Model for End-Stage Liver Disease; NS, not significant; OLT, orthotopic liver transplantation; SD, standard deviation.

See Mazzaferro et al. 27

Outcomes on the Transplant Waiting List

Probability of Transplantation

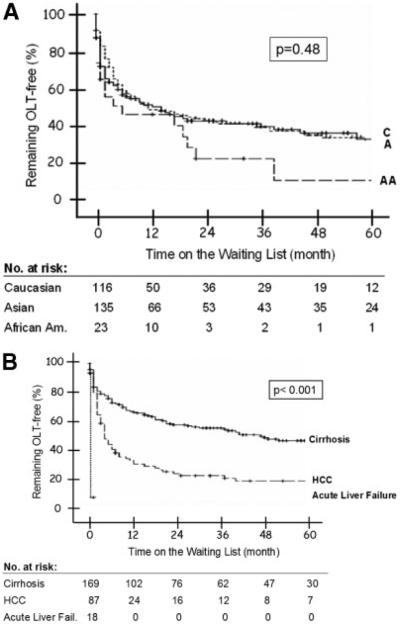

During a mean follow-up of 22.9 ± 28.7 [median 8 (range 0-127)] months from listing, 170 (62%) patients had been transplanted, including 74% of African Americans, 61% of Asian Americans, and 59% of Caucasians (Table 3). African Americans had the highest probability of undergoing transplantation, but the difference among the 3 groups was not statistically significant (P = 0.487; Fig. 1A). The probability of transplantation 1, 3, and 5 years after listing was 53%, 75%, and 88% for African Americans, 48%, 58%, and 66% for Asian Americans, and 48%, 57%, and 63% for Caucasians. As expected, the interval between listing and transplantation was shortest for patients with acute liver failure, and they were followed by those with HCC and those with end-stage cirrhosis (Fig. 1B). All patients with acute liver failure were transplanted within 8 days, while the probability of transplantation 1, 3, and 5 years after listing was 68%, 79%, and 83% for those listed for HCC and 34%, 46%, and 55% for those listed for end-stage cirrhosis (P < 0.001). Cox regression analysis showed that transplant indication (P < 0.001) and MELD score for end-stage cirrhosis patients (P = 0.001) were the only predictors of transplantation; race was not.

TABLE 3.

Pretransplant Outcomes

| Pretransplant Outcomes |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Caucasians | Asian Americans |

African Americans |

All | |

| No. of patients at listing | 116 | 135 | 23 | 274 |

| No. transplanted | 68/116 (58.7) | 85/135 (61.4) | 17/23 (73.9) | 170/274 (62.0) |

| No. that died on waiting list | 15/116 (12.9) | 6/135 (4.4) | 3/23 (13.0) | 24/274 (8.7) |

| End-stage cirrhosis | 12/87(13.7) | 3/67 (4.4) | 3/15 (20.0) | 18/169 (10.7) |

| HCC | 3/19 (15.7) | 3/64 (4.6) | 0/4 (0) | 6/87 (6.8) |

| Acute liver failure | 0/10 (0) | 0/4 (0) | 0/4 (0) | 0/18(0) |

| Cause of death | ||||

| HCC | 2 | 2 | 0 | 4/24 (16.7) |

| Other liver causes | 7 | 4 | 3 | 14/24 (58.3) |

| Non-liver | 6 | 0 | 0 | 6/24 (25.0) |

| No. of dropouts from waiting list | 16/116 (13.7) | 8/135 (5.9) | 3/23 (13.0) | 27/274 (9.8) |

| Cirrhosis | 13/87 (14.9) | 3/67 (4.4) | 3/15 (20.0) | 19/169 (11.2) |

| HCC | 3/19 (15.7) | 5/64 (7.8) | 0/4 (0) | 8/87 (9.1) |

| Acute liver failure | 0/10 (0) | 0/4 (0) | 0/4 (0) | 0/18 (0) |

| No. with new HCC diagnosis | 14/87 (16.0) | 8/67 (11.9) | 1/15 (6.6) | 23/169 (13.6) |

| Diagnosed on the waiting list | 8 | 7 | 0 | 15 |

| Diagnosed on explant liver | 6 | 1 | 1 | 8 |

NOTE: The results are expressed as number (%).

Abbreviation: HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma.

Figure 1.

Probability of undergoing OLT (A) by race and (B) according to transplant indication. Log rank P value for race: 0.48; log rank P value for transplant indication: <0.001. Abbreviations: A, Asian Americans; AA, African Americans; C, Caucasians; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; OLT, orthotopic liver transplantation.

Waitlist Mortality

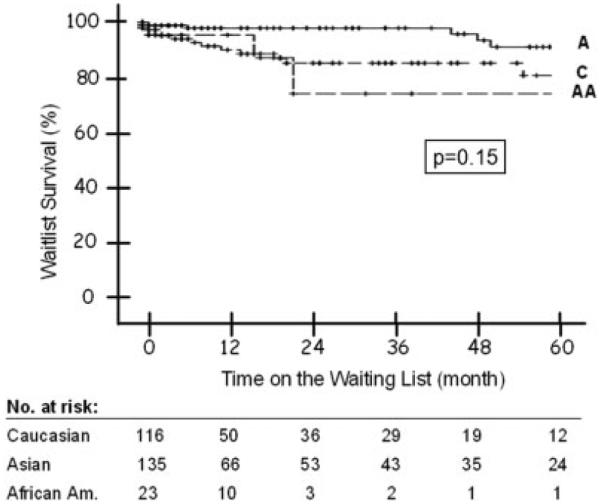

A total of 24 patients died while on the transplant waiting list, including 6 (4%) Asian Americans, 15 (13%) Caucasians, and 3 (13%) African Americans (Table 3). The probability of waitlist mortality at 1, 3, and 5 years was 3%, 3%, and 12% for Asian Americans, 10%, 18%, and 23% for Caucasians, and 6%, 31%, and 31% for African Americans (P = 0.15; Fig. 2). Cox regression analysis found that race, transplant indication, MELD score at listing among patients with end-stage cirrhosis, and tumor stage among patients with HCC did not predict waitlist mortality. Pairwise comparisons showed that Asian Americans had significantly lower waitlist mortality than Caucasians when all deaths were included, even after adjustments for transplant indication and listing MELD (P = 0.05). However, this difference was not significant when only liver-related deaths were analyzed (P = 0.14).

Figure 2.

Probability of death on the waiting list by race. Log rank P value: 0.15. Abbreviations: A, Asian Americans; AA, African Americans; C, Caucasians.

Dropout

Only 3 patients (1 Caucasian and 2 Asians) were removed from the waiting list because of disease progression (Table 3). Therefore, the probability of dropout (death or removal from the waiting list due to disease progression) in the 3 groups was similar to the probability of waitlist mortality.

New HCC Diagnosis While on the Waiting List

Of the 169 patients who had end-stage cirrhosis and no HCC at listing, 23 (14%) had a new HCC diagnosis while on the waiting list, including 14 (16%) Caucasians, 8 (12%) Asian Americans, and 1 (7%) African American (Table 3). The probability of a new HCC diagnosis while on the waiting list was similar in the 3 racial groups (data not shown).

Characteristics of the Transplanted Patients

Characteristics of the 170 patients who underwent liver transplantation are listed in Table 4. The 3 racial groups were comparable, except for a younger age among African Americans and a higher proportion listed for HCC among Asian Americans. The 3 groups were also similar with respect to the proportion of patients receiving antiviral therapy, experiencing virological breakthrough or confirmed genotypic resistance pre-transplant, or having serum HBV DNA levels > 5 log10 copies/mL at the time of transplant. All except 5 patients (97%) received a combination of antiviral therapy and HBIG post-transplant. There was no difference in HBIG regimens among the 3 racial groups.

TABLE 4.

Characteristics of the Transplanted Patients

| Characteristics of the Transplanted Patients |

P Values |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C Versus As Versus | C Versus | C Versus | |||||

| C | As | AA | All | AA | As | AA | |

| No. of patients | 68 (40.0) | 85 (50.0) | 17 (10.0) | 170 (100) | |||

| Gender, male | 53 (78.0) | 63 (74.1) | 13 (76.5) | 129 (75.9) | NS | NS | NS |

| Age, years (mean ± SD) | 53.1 ± 8.6 | 53.0 ± 10.5 | 43.0 ± 14.9 | 51.9 ± 10.7 | 0.001 | NS | <0.001 |

| OLT indication | 0.008 | 0.014 | NS | ||||

| End-stage cirrhosis | 30 (44.2) | 26 (30.5) | 8 (47.0) | 64 (37.6) | NS | NS | NS |

| HCC | 29 (42.6) | 55 (64.7) | 5 (29.4) | 89 (52.4) | 0.003 | 0.006 | NS |

| Acute liver failure | 9 (13.2) | 4 (4.8) | 4 (23.6) | 17 (10.0) | 0.032 | 0.06 | NS |

| Labs at transplantation | |||||||

| HBeAg (+) | 15/56 (26.8) | 18/69 (21.2) | 4/13 (23.5) | 37/138 (26.8) | NS | NS | NS |

| HBV DNA detectable | 43/64 (67.2) | 46/71 (54.1) | 9/16 (52.9) | 98/151 (64.9) | NS | NS | NS |

| Log10 copies/mL (mean ± SD) | 4.2 ± 2.4 | 4.2 ± 0.2 | 3.7 ± 0.5 | 4.1 ± 2.2 | NS | NS | NS |

| HBV DNA > 5 log10 copies/mL | 25/43 (58.1) | 29/46 (63.0) | 4/9 (44.4) | 58/98 (59.1) | NS | NS | NS |

| ALT, U/L | 58 (13–2796) | 49 (20–3543) | 76 (13–1649) | 53 (13–3543) | NS | NS | NS |

| AST, U/L | 80 (16–6270) | 66 (24–3907 | 71 (30–1946) | 71 (16–6270) | NS | NS | NS |

| Bilirubin, mg/dL | 2.8 (0.5–39) | 2.1 (0.4–59.4) | 5.4 (0.3–24.9) | 2.6 (0.3–59.4) | NS | NS | NS |

| INR | 1.5 (1–7.3) | 1.4 (0.8–4.8) | 1.8 (1.1–4.4) | 1.5 (0.8–7.3) | NS | NS | NS |

| Creatinine, mg/dL | 1.1 (0.1–7.8) | 1.0 (0.5–6) | 1.0 (0.5–9) | 1.5 (0.1–9.0) | NS | NS | NS |

| End-stage cirrhosis: lab MELD | 20 (9–38) | 21 (8–40) | 23 (11–40) | 21 (8–40) | NS | NS | NS |

| HCC: within Milan criteria* | 11/24 (45.3) | 27/52 (52.0) | 3/4 (75.0) | 41/80 (51.2) | NS | NS | NS |

| Antiviral treatment pre-OLT† | 49 (72.0) | 66 (77.6) | 10 (58.8) | 125 (73.5) | NS | NS | NS |

| Breakthrough pre-OLT | 9/49 (18.3) | 10/66 (15.1) | 3/10 (30) | 22/125 (17.6) | NS | NS | NS |

| Confirmed genotypic resistance pre-OLT‡ | 4/5 (80.0) | 5/6 (83.3) | 2/3 (66.6) | 11/14 (78.5) | NS | NS | NS |

| HBV prophylactic regimen post-OLT | |||||||

| HBIG + antiviral | 67 (98.5) | 82 (96.4) | 16 (94.1) | 165 (97.0) | NS | NS | NS |

| HBIG only | 0 (0) | 1 (1.1) | 0 (0) | 1 (0.5) | |||

| Antiviral only | 1 (1.5) | 2 (2.3) | 1 (5.9) | 4 (2.3) | |||

| No. of patients treated for rejection | 7 (10.2) | 14 (16.4) | 2 (11.7) | 23 (13.5) | NS | NS | NS |

| Duration of steroid use, months | 5 (0–27) | 7 (0–17) | 7 (3–13) | 6 (0–27) | NS | NS | NS |

NOTE: The results are expressed as number (%) or median (range) unless specified otherwise.

Abbreviations: ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AA, African Americans; As, Asian Americans; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; C, Caucasians; HBeAg, hepatitis B e antigen; HBIG, hepatitis B immune globulin; HBV, hepatitis B virus; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; INR, international normalized ratio; MELD, Model for End-Stage Liver Disease; NS, not significant; OLT, orthotopic liver transplantation; SD, standard deviation.

See Mazzaferro et al.27

Ninety-eight of 123 (76.4%) patients transplanted after September 2002 when adefovir was approved were on antiviral therapy at the time of transplant versus 27 of 47 (57.1%) patients transplanted before September 2002.

Fourteen of 22 patients with virological breakthrough pre-transplant with blood samples collected prior to the initiation of rescue therapy were tested for antiviral resistance

Post-Transplant Outcomes

Post-Transplant Survival

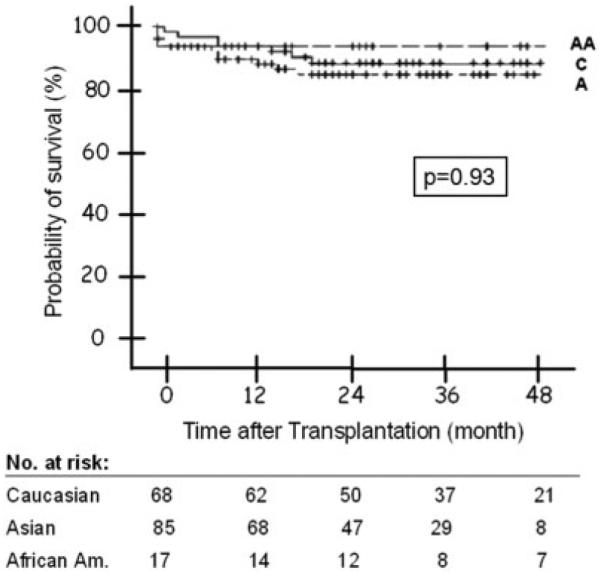

During a median follow-up of 31 months (range 0-67), 19 patients died, including 1 (6%) African American, 11 (13%) Asian Americans, and 7 (10%) Caucasians (Table 5). The probability of post-transplant survival at 1, 3, and 5 years was 94%, 94%, and 94% for African Americans, 90%, 85%, and 85% for Asian Americans, and 94%, 89%, and 89% for Caucasians (P = 0.93; Fig. 3). Cox regression analysis found that HCC recurrence was the only predictor of post-transplant mortality, while race, indication for transplant, and HBV recurrence were not.

TABLE 5.

Post-Transplant Outcomes

| Post-Transplant Outcomes |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Caucasians | Asian Americans | African Americans | All | |

| No. of transplanted patients | 68/116 (58.7) | 85/135 (61.4) | 17/23 (73.9) | 170/274 (62.0) |

| No. that died | 7/68 (10.2) | 11/85 (12.9) | 1/17 (5.8) | 19/170 (11.1) |

| Cause of death | ||||

| Recurrent HCC | 3 | 2 | 0 | 5 |

| Other liver causes | 2 | 3 | 0 | 5 |

| Peritransplant complications | 0 | 3 | 1 | 4 |

| Other non-liver causes | 2 | 3 | 0 | 5 |

| No. with HBV recurrence | 10/68 (14.7) | 2/85 (2.3) | 1/17 (5.8) | 13/170 (7.6) |

| No. with HCC recurrence | 3/29 (10.0) | 4/55 (7.2) | 0/5 (0) | 7/89 (7.7) |

NOTE: The results are expressed as number (%).

Abbreviations: HBV, hepatitis B virus; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma.

Figure 3.

Probability of post-transplant survival by race. Log rank P value: 0.93. Abbreviations: A, Asian Americans; AA, African Americans; C, Caucasians.

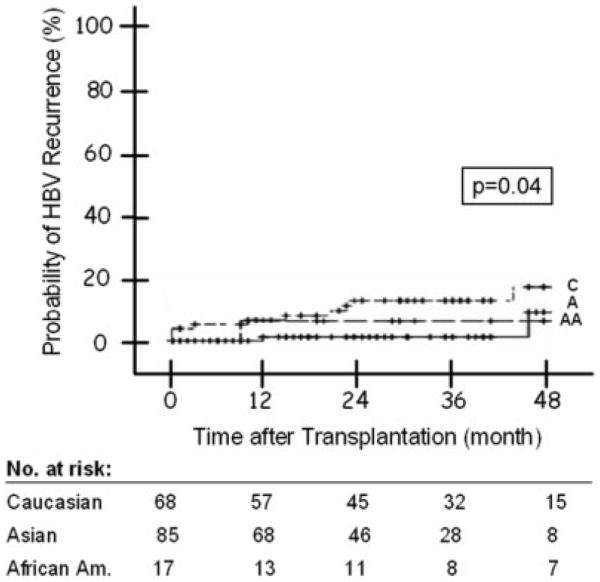

HBV Recurrence

A total of 13 (8%) patients had HBV recurrence, including 1 (1%) Asian American, 1 (6%) African American, and 11 (16%) Caucasians (Table 5). Univariate analysis showed that the probability of HBV recurrence was significantly higher among Caucasians (P = 0.043). The probability of HBV recurrence at 1, 2, and 4 years post-transplant was 0%, 2%, and 7% for Asian Americans, 6%, 6%, and 6% for African Americans, and 8%, 13%, and 19% for Caucasians (Fig. 4). Cox regression analysis found that HBeAg status at listing (P = 0.003) was the only factor significantly associated with HBV recurrence post-transplant, while race showed a trend (P = 0.057; Table 6).

Figure 4.

Figure 4. Probability of post-transplant HBV recurrence by race. Log rank P value: 0.04. Abbreviations: A, Asian Americans; AA, African Americans; C, Caucasians; HBV, hepatitis B virus.

TABLE 6.

Multivariate Analysis of Factors Associated with HBV Recurrence

| Factors Associated with HBV Recurrence |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| P Value | Hazard Ratio | 95% CI | |

| Listing HBeAg | 0.003 | 12.903 | 2.368–70.321 |

| Race | 0.057 | 0.512 | 0.168–1.162 |

| HBV DNA at transplant > 5 log10 copies/mL | 0.624 | 0.536 | 0.272–8.769 |

| Transplant date after 09/2002* | 0.655 | 0.712 | 0.161–3.150 |

| Center | 0.936 | 0.962 | 0.966–1.124 |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; HBeAg, hepatitis B e antigen; HBV, hepatitis B virus.

Date when adefovir was approved.

HCC Recurrence

A total of 89 patients had HCC: 68 at listing, 13 while on the waiting list, and 8 on explant liver. Of these, 7 (8%) had HCC recurrence, including 3 (10%) Caucasians and 4 (7%) Asian Americans. The probability of HCC recurrence at 1, 2, and 4 years was 4%, 4%, and 4% for Caucasians, 1%, 5%, and 7% for Asian Americans, and 0%, 0%, and 0% for African Americans (P = 0.50).

DISCUSSION

This large study included 274 patients listed for liver transplantation for HBV infection in 15 centers distributed across the United States, providing a good representation of HBV patients in this country. We found that Asians constituted half (49.2%) of the study population. This is not surprising because hepatitis B is endemic in Asian countries and many studies have reported a high prevalence (10%-15%) of chronic HBV infection among Asian Americans.13-15 The National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey found that the prevalence of HBV infection is 4-fold higher among African Americans versus whites.16 It is surprising to see that a low percentage of patients listed for liver transplantation for HBV infection were African Americans. This discrepancy may be related to differences in access to transplantation.17 We found that African Americans listed for end-stage cirrhosis had similar MELD scores and those listed for HCC had similar tumor staging at listing in comparison with Caucasians and Asian Americans. However, this does not preclude the possibility that fewer African Americans are referred to liver transplant centers or the possibility that more African Americans are referred too late and are not eligible for listing. Interestingly, African Americans were significantly younger at listing. This is surprising because African Americans likely acquired HBV infection during childhood or adult life, while Asian Americans likely acquired HBV infection perinatally or during early childhood. These data suggest that African Americans with chronic HBV infection may have a more rapidly progressive course.

Asian Americans were 3 times as likely to be listed for HCC as Caucasians or African Americans. The higher propensity for HCC may be related to a longer duration of HBV infection among Asian Americans, in whom infection likely occurred at a younger age, or to other factors such as HBV genotype, host genetics, or environmental factors (eg, aflatoxin). Many studies have shown that HBV genotype C, which is common in Asian countries and among Asian Americans, is associated with a higher risk of HCC than HBV genotype B.18-21 A previous analysis of a subset of patients in the NIH HBV-OLT study for whom HBV genotype data were available showed that patients with genotype C infection were significantly more likely to have HCC at listing than those with genotype non-C (A, B, or D).22 Once listed, the rate of new HCC diagnosis was similar in all 3 racial groups, underscoring the importance of HCC surveillance for all patients with HBV-related cirrhosis, regardless of race.

Despite differences in age at infection and therefore duration of infection, the prevalence of HBeAg, the percentage of patients with detectable serum HBV DNA, and the mean serum HBV DNA levels at listing were similar in the 3 racial groups. Persistence of HBeAg and high serum HBV DNA levels after a longer duration of infection may have contributed to the high rate of HCC among Asian Americans.23,24 Similar percentages of patients in all 3 groups were receiving antiviral therapy at listing and at the time of transplant, and this indicated that there was no racial barrier to access to antiviral therapy.

Previous studies found that African Americans were less likely to be transplanted17,25,26; however, in this study, we found that African Americans were more likely to be transplanted, but the number of African Americans included was small. Moreover, the anomalous finding may be related to the fact that more African Americans were listed with acute liver failure, and those with end-stage cirrhosis had slightly higher MELD scores at listing. Multivariate Cox regression analysis showed that transplant indication was a significant predictor of time to transplant, but race was not. This finding confirms that the current system of organ allocation (sickest first) is fair across racial groups. Our study also showed that outcomes on the waiting list (waitlist mortality as well as dropout rate) were comparable among Caucasians, Asian Americans, and African Americans.

In accordance with the results of Lee et al.’s study,4 racial disparity in post-transplant survival was not observed among patients who underwent OLT in an era when nucleos/tide analogues and HBIG prophylaxis are routinely used and the Milan criteria are applied to patients with HCC.27 In fact, our study found a very high rate of post-transplant survival among African Americans: a 5-year probability of 94% versus 85% for Asian Americans and 89% for Caucasians. The only independent risk factor for mortality after liver transplant was recurrence of HCC. Although the rate of HCC recurrence was similar among the 3 racial groups, a higher proportion of patients transplanted for HCC may explain the slightly lower rate of post-transplant survival among Asian Americans. The disparity in the proportion of patients transplanted for HCC might have contributed to a higher rate of post-OLT mortality among Asian Americans in the era prior to the application of the Milan criteria.

A surprising finding was a higher HBV recurrence rate among Caucasians. Three studies performed in the 1990s reported similar or higher HBV recurrence rates among Asian Americans. One study of 15 Asians and 29 non-Asians reported a significantly higher rate of HBV recurrence among Asians: 72% versus 32% (P < 0.05).6 Another study of 15 Asians and 20 non-Asians did not observe any difference in HBV recurrence rates between the 2 groups.7 A third study of 70 Asians and 99 whites reported similar rates of HBV recurrence: 11% versus 12%.8 In the current study, the probability of HBV recurrence 4 years post-transplant was 19% among Caucasians, 7% among Asian Americans, and 6% among African Americans (P = 0.043) despite similar HBeAg and HBV DNA status (at listing and at transplant), use of antiviral therapy pre-transplant, occurrence of virological breakthrough/confirmed genotypic resistance to antiviral therapy pre-transplant, and use of antiviral and HBIG prophylaxis post-transplant.

In summary, in this large retrospective-prospective study involving 274 patients with HBV listed for liver transplantation in the United States, we found similar waitlist and post-transplant outcomes among Caucasians, Asian Americans, and African Americans. There were some differences among these 3 racial groups. Asian Americans were significantly more likely to be listed for HCC, but HCC recurrence rates were similar to those of Caucasians and African Americans. African Americans were significantly younger and had a higher rate of transplantation, which is likely related to the higher proportion with acute liver failure. A surprising finding was a higher rate of HBV recurrence among Caucasians. This finding is inexplicable and needs to be validated. We acknowledge that the number of African Americans included in this study is small (23 in total and 17 transplanted), and patients who are approved for listing for liver transplantation may not represent the patient population at large. Nevertheless, our data indicate that Caucasians, Asian Americans, and African Americans with hepatitis B can be managed similarly in the transplant setting and can expect to have similar outcomes on the waiting list and after transplantation.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We thank all the investigators and study staff at the participating sites:

California Pacific Medical Center, San Francisco, CA: Natalie Bzowej, M.D., Robert Gish, M.D., and Jamie Zagorski, R.N.

Cedars Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles, CA: Tram Tran, M.D., and Amy Crumley, R.N.

Columbia University, New York, NY: Paul Gaglio, M.D., and Maria Martin.

Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA: Raymond T. Chung, M.D., Diana Tsui, and Marian Bihrle. Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN: Michael Ishitani, M.D., and Heidi Togerson, R.N.

Mount Sinai University Medical Center, New York, NY: Sukru Emre, M.D., Mark Sturdevant, M.D., and Javaluyas Aniceto, M.D.

Ochsner Clinic, New Orleans, LA: Robert Perrillo, M.D., and Cheryl Denham, L.P.N.

Stanford University, Palo Alto, CA: Emmet Keeffe, M.D., and Lucinda Porter, R.N.

University of California, Los Angeles, CA: Steve Han, M.D., Pearl Kim-Hong, and Val Peacock, R.N.

University of Florida, Gainesville, FL: Consuelo Soldevila-Pico, M.D., and Joy Peter, R.N., B.S.N.

University of Miami, Miami, FL: Eugene Schiff, M.D., and Maria Torres.

University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA: Rajender Reddy, M.D., and Timothy Siropaides.

University of Virginia, Charlottesville, VA: Timothy Pruett, M.D.

Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond, VA: Velimir A. C. Luketic, M.D., and Stacy McLeod.

University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI: Anna Lok, M.D., Bulent Degertekin, M.D., Terese Howell, Donna Harsh, Munira Hussain, Jim Imus, and Morton Brown, Ph.D.

This study was supported by a National Institutes of Health grant (U01 DK57577 to Anna S. Lok). Roche Molecular Diagnostics provided Amplicor kits for the hepatitis B virus DNA assays.

Abbreviations

- ALT

alanine aminotransferase

- AST

aspartate aminotransferase

- CI

confidence interval

- HBeAg

hepatitis B e antigen

- HBIG

hepatitis B immune globulin

- HBV

hepatitis B virus

- HCC

hepatocellular carcinoma

- INR

international normalized ratio

- MELD

Model for End-Stage Liver Disease

- NIH

National Institutes of Health

- NS

not significant

- OLT

orthotopic liver transplantation

- SD

standard deviation

- UNOS

United Network of Organ Sharing

Footnotes

Sukru Emre is currently affiliated with Yale University, New Haven, CT.

REFERENCES

- 1.Moore DE, Feurer ID, Rodgers S, Jr, Shaffer D, Nylander W, Gorden DL, et al. Is there racial disparity in outcomes after solid organ transplantation? Am J Surg. 2004;188:571–574. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2004.07.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nair S, Eustace J, Thuluvath PJ. Effect of race on outcome of orthotopic liver transplantation: a cohort study. Lancet. 2002;359:287–293. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)07494-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Roberts MS, Angus DC, Bryce CL, Valenta Z, Weissfeld L. Survival after liver transplantation in the United States: a disease-specific analysis of the UNOS database. Liver Transpl. 2004;10:886–897. doi: 10.1002/lt.20137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lee TH, Shah N, Pedersen RA, Kremers WK, Rosen CB, Klintmalm GB, et al. Survival after liver transplantation: is racial disparity inevitable? Hepatology. 2007;46:1491–1497. doi: 10.1002/hep.21830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jacobs JM, Martin P, Munoz SJ, Westerberg S, Hann HW, Moritz MJ, et al. Liver transplantation for chronic hepatitis B in Asian males. Transplant Proc. 1993;25:1904–1906. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jurim O, Martin P, Shaked A, Goldstein L, Millis JM, Calquhoun SD, et al. Liver transplantation for chronic hepatitis B in Asians. Transplantation. 1994;57:1393–1395. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199405150-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ho BM, So SK, Esquivel CO, Keeffe EB. Liver transplantation in Asian patients with chronic hepatitis B. Hepatology. 1997;25:223–225. doi: 10.1002/hep.510250140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Teo EK, Han SH, Terrault N, Luketic V, Jensen D, Keeffe EB, et al. Liver transplantation in patients with hepatitis B virus infection: outcome in Asian versus white patients. Hepatology. 2001;34:126–132. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2001.25271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kim WR, Poterucha JJ, Kremers WK, Ishitani MB, Dickson ER. Outcome of liver transplantation for hepatitis B in the United States. Liver Transpl. 2004;10:968–974. doi: 10.1002/lt.20217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wong SN, Reddy KR, Keeffe EB, Han SH, Gaglio PJ, Perrillo RP, et al. Comparison of clinical outcomes in chronic hepatitis B liver transplant candidates with and without hepatocellular carcinoma. Liver Transpl. 2007;13:334–342. doi: 10.1002/lt.20959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tan J, Degertekin B, Wong SN, Husain M, Oberhelman K, Lok AS. Tenofovir monotherapy is effective in hepatitis B patients with antiviral treatment failure to adefovir in the absence of adefovir-resistant mutations. J Hepatol. 2008;48:391–398. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2007.09.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Degertekin B, Hussain M, Tan J, Oberhelman K, Lok AS. Sensitivity and accuracy of an updated line probe assay (HBV DR v.3) in detecting mutations associated with hepatitis B antiviral resistance. J Hepatol. 2009;50:42–48. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2008.08.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Screening for chronic hepatitis B among Asian/Pacific Islander populations—New York City, 2005. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2006;55:505–509. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Guane R, Siu P, Lam K, Kim KE, Warren V, Liu H, et al. Prevalence of HBV and risk of HBV acquisition in hepatitis B screening programs in large metropolitan cities in the United States. Hepatology. 2004;40:716A. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lin SY, Chang ET, So SK. Why we should routinely screen Asian American adults for hepatitis B: a cross-sectional study of Asians in California. Hepatology. 2007;46:1034–1040. doi: 10.1002/hep.21784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McQuillan GM, Coleman PJ, Kruszon-Moran D, Moyer LA, Lambert SB, Margolis HS. Prevalence of hepatitis B virus infection in the United States: the National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys, 1976 through 1994. Am J Public Health. 1999;89:14–18. doi: 10.2105/ajph.89.1.14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Epstein AM, Ayanian JZ, Keogh JH, Noonan SJ, Armistead N, Cleary PD, et al. Racial disparities in access to renal transplantation—clinically appropriate or due to underuse or overuse? N Engl J Med. 2000;343:1537–1544. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200011233432106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sumi H, Yokosuka O, Seki N, Arai M, Imazeki F, Kurihara T, et al. Influence of hepatitis B virus genotypes on the progression of chronic type B liver disease. Hepatology. 2003;37:19–26. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2003.50036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yuen MF, Sablon E, Yuan HJ, Wong DK, Hui CK, Wong BC, et al. Significance of hepatitis B genotype in acute exacerbation, HBeAg seroconversion, cirrhosis-related complications, and hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology. 2003;37:562–567. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2003.50098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chan HL, Hui AY, Wong ML, Tse AM, Hung LC, Wong VW, et al. Genotype C hepatitis B virus infection is associated with an increased risk of hepatocellular carcinoma. Gut. 2004;53:1494–1498. doi: 10.1136/gut.2003.033324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yu MW, Yeh SH, Chen PJ, Liaw YF, Lin CL, Liu CJ, et al. Hepatitis B virus genotype and DNA level and hepatocellular carcinoma: a prospective study in men. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2005;97:265–272. doi: 10.1093/jnci/dji043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gaglio P, Singh S, Degertekin B, Ishitani M, Hussain M, Perrillo R, et al. Impact of the hepatitis B virus genotype on pre- and post-liver transplantation outcomes. Liver Transpl. 2008;14:1420–1427. doi: 10.1002/lt.21563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yang HI, Lu SN, Liaw YF, You SL, Sun CA, Wang LY, et al. Hepatitis B e antigen and the risk of hepatocellular carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:168–174. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa013215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chen CJ, Yang HI, Su J, Jen CL, You SL, Lu SN, et al. Risk of hepatocellular carcinoma across a biological gradient of serum hepatitis B virus DNA level. JAMA. 2006;295:65–73. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.1.65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kasiske BL, Neylan JF, III, Riggio RR, Danovitch GM, Kahana L, Alexander SR, et al. The effect of race on access and outcome in transplantation. N Engl J Med. 1991;324:302–307. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199101313240505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Eckhoff DE, McGuire BM, Young CJ, Sellers MT, Frenette LR, Hudson SL, et al. Race: a critical factor in organ donation, patient referral and selection, and orthotopic liver transplantation? Liver Transpl Surg. 1998;4:499–505. doi: 10.1002/lt.500040606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mazzaferro V, Regalia E, Doci R, Andreola S, Pulvirenti A, Bozzetti F, et al. Liver transplantation for the treatment of small hepatocellular carcinomas in patients with cirrhosis. N Engl J Med. 1996;334:693–699. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199603143341104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]