Abstract

Background:

Major depressive disorder has been associated with abnormal resting-state functional connectivity (FC), especially in cognitive processing and emotional regulation networks. Although studies have found abnormal FC in regions of the default mode network (DMN), no study has investigated the FC of specific regions within the anterior DMN based on cytoarchitectonic subdivisions of the antero-medial pre-frontal cortex (PFC). Studies from different areas in the field have shown regions within the anterior DMN to be involved in emotional intelligence. Although abnormalities in this region have been observed in depression, the relationship between the ventromedial PFC (vmPFC) function and emotional intelligence has yet to be investigated in depressed individuals.

Methods:

Twenty-one medication-free, non–treatment resistant, depressed patients and 21 healthy controls underwent a resting state functional magnetic resonance imaging session. The participants also completed an ability-based measure of emotional intelligence: the Mayer-Salovey-Caruso Emotional Intelligence Test. FC maps of Brodmann areas (BA) 25, 10m, 10r, and 10p were created and compared between the two groups.

Results:

Mixed-effects analyses showed that the more anterior seeds encompassed larger areas of the DMN. Compared to healthy controls, depressed patients had significantly lower connectivity between BA10p and the right insula and between BA25 and the perigenual anterior cingulate cortex. Exploratory analyses showed an association between vmPFC connectivity and emotional intelligence.

Conclusions:

These results suggest that individuals with depression have reduced FC between antero-medial PFC regions and regions involved in emotional regulation compared to control subjects. Moreover, vmPFC functional connectivity appears linked to emotional intelligence.

Keywords: anterior medial PFC, emotional intelligence, major depression, MSCEIT, resting state functional connectivity

Background

Major depressive disorder (MDD) is characterized by persistent feelings of sadness, worthlessness, and guilt, as well as cognitive and physical symptoms that affect daily life functioning (APA, 2000). Positron Emission Tomography (PET) and functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) studies have revealed abnormal neural functioning in depression within cortical regions involved in cognitive control and emotional regulation and subcortical regions involved in affective processing and visceral functions. Using resting-state functional brain imaging techniques, researchers have shown that MDD is associated with hypoactivity in cognitive control brain regions, especially pregenual anterior cingulate, posterior cingulate, and middle frontal gyri and affective control cortical regions such as insula. Regions considered overactive in MDD include deeper brain structures such as the thalamus and caudate, among others (Fitzgerald et al., 2008).

The default mode network (DMN), a key network activated during rest and thought to reflect self-directed thinking, has also been found to be abnormal in depression. Studies have generally reported increased functional connectivity (FC) in depressed subjects within different regions of the DMN, including the subgenual anterior cingulate cortex (ACC) and posterior cingulate cortex (PCC; Greicius et al., 2007; Zhu et al., 2012; Li et al., 2013; Sambarto et al., 2013). Investigators have also observed increases in FC of the PCC with the orbitomedial pre-frontal cortex (PFC) and dorsolateral PFC in acute depression (Zhou et al., 2010) and of the PCC with the medial temporal lobe in remitted depression (Wu et al., 2013). Findings of reduced FC are most frequently found between cortical and subcortical regions, for example between the ACC and medial thalamus and pallidostriatum (Anand et al., 2005), the ventromedial PFC (vmPFC), and the cerebellum (Liu et al., 2012), and the middle frontal gyrus with the hippocampus (Cao et al., 2012; a noteworthy exception is increased FC between the frontal poles and cerebellum [Liu et al., 2012]).

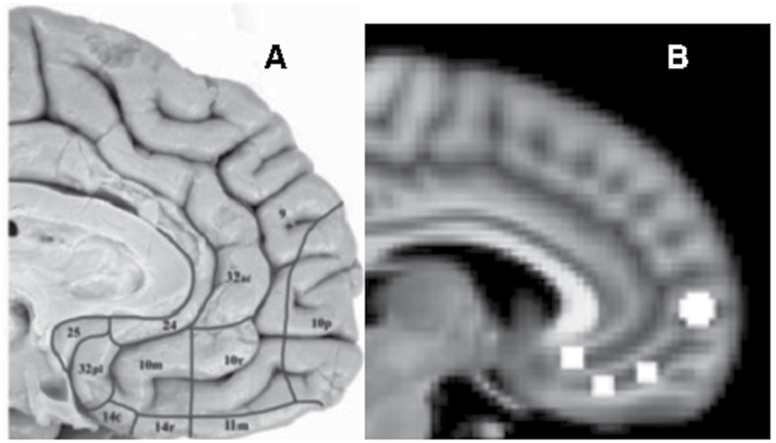

The subgenual ACC (Brodmann area 25), with its extensive connections to cortical and subcortical regions (Price and Drevets, 2010), was proposed as a critical node in the DMN of depressed and at-risk individuals. This region’s metabolic activity is elevated in acutely depressed individuals—normalizing after remission—and in healthy controls induced into a sad state (Mayberg et al., 1999). Another important region in the DMN is the anteromedial PFC, often referred to as Brodmann area 10 (BA10). Cytoarchitechtonic subdivisions of this region, however, show that BA10 not only covers the frontal pole but extends ventrally to include the vmPFC and anterior-most region of the subcallosal area. The frontal pole is therefore referred to as BA10p, with the vmPFC regions as BA10m and BA10r (Figure 1A). BA10p is the largest region of the prefrontal lobe (Ongur et al., 2003), which may reflect the complexity of cognitive-related computational processes undertaken by this brain region (Rolls, 2014).

Figure 1.

(A) Cytoarchitectonic subdivisions of the anteromedial pre-frontal cortex (Ongur et al., 2003). BA10 is divided into BA10p, BA10r, and BA10m. (B) Seed regions (right hemisphere shown). Anterior to posterior: BA10p, BA10r, BA10m, and BA25. BA, Brodmann areas.

Mood and psychomotor problems in depression have been considered to be the critical symptoms that necessitate immediate intervention. Recent investigations in social cognition, however, have suggested abnormal processing of social emotional stimuli in individuals with depression. Some studies looked at emotion recognition of facial expressions in depression and found evidence for a negative bias toward sad faces and reduced accuracy in the recognition of emotion in faces (Bourke et al., 2010). Other studies focused on trait- and ability-based measures of emotional intelligence (EI). Those studies found that higher depressive symptoms predict lower emotional intelligence in male subjects (Salguero et al., 2012), MDD participants exposed to trauma have lower EI scores than healthy controls (Kwako et al., 2011), and older adults with higher EI scores have a lower risk of developing depression (Lloyd et al., 2012). Although a clear understanding of the neurobiological correlates of social emotional deficits in depression is still lacking, evidence from neuropsychology, cognitive psychology, and brain imaging has implicated the vmPFC in the proper expression of emotion (Damasio, 1996), understanding of emotion from body language (Mah et al., 2005), and emotional decision-making (Bechara and Damasio, 2005; Rolls, 2014). Results from these studies could suggest that low EI relates to depression through a mechanism involving a reduced ability to recognize and manage emotions, a cognitive process undertaken by the vmPFC (Downey et al., 2008).

Based on evidence supporting the functionally diverse nature of the DMN (Smith et al., 2012) and the anatomical subdivision of BA 10, the first aim of this study was to investigate whether four distinct frontal sub-regions (BA25, BA10m, BA10r, and BA10p) extending from the subcallosal cortex beneath the rostrum to the inferior-most regions of the medial frontal cortex encompassing the frontal poles show different functional connectivity maps between depressed and healthy subjects. The second aim was to determine whether FC of the anterior DMN is related to emotional intelligence in depressed and healthy subjects. Although the relationship between social cognition and depression remains tenuous, this study aims at building on the growing literature linking emotional intelligence to depressive symptomatology and providing a biological framework to help understand the underlying mechanisms of social and emotional deficits in depression.

Methods

Participants

Participants were recruited from the Medical University of South Carolina (MUSC) outpatient psychiatric services, the Mood Disorders Program (MDP), and local advertisements for two separate but consecutively-executed studies with similar inclusion criteria and with identical research personnel. The depressed participants were recruited strictly for the neuroimaging studies. All participants provided informed consent as approved by the Institutional Review Board at MUSC. Patients with depression met criteria for a major depressive episode based on a Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I disorders (First et al., 1996). Criteria for inclusion were symptom duration of less than 24 months and an Antidepressant Treatment History Form ≤ 1 (Sackeim et al., 1990). Prior to the scan, patients were off psychotropic medication for at least two weeks (at least four weeks for Fluoxetine). Exclusion criteria included psychotic disorders, substance abuse or dependence, neurodegenerative disorders, epileptic disorders, serious medical conditions, and pregnancy. Healthy subjects were recruited through advertisements and screened for DSM-IV-TR Axis I disorders (except caffeine and nicotine abuse).

Assessments

An experienced clinical rater completed the 24-item Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression. Participants completed the Inventory of Depressive Symptoms–Self Report scale (IDS-SR; Rush et al., 1996), the State and Trait Anxiety Inventory-Y2 (Spielberger, 1983), the Empathy Quotient (Lawrence et al., 2004), and the Affective Neuroscience Personality Scale (Davis and Panksepp, 2011). They also completed an ability-based measure of emotional intelligence, the Mayer-Salovey-Caruso Emotional Intelligence Test (MSCEIT). The MSCEIT is a behavioral task that directly tests one’s ability to identify emotional expressions in faces, to judge how a person might feel in a certain situation, and to identify behaviors that contribute to different emotional states. Two sub-scores are reported: (1) Experiential Emotional Intelligence subscore, which captures the ability to accurately perceive, identify and classify emotions and involves the processing of emotion at a basic level; and 2) Strategic Emotional Intelligence subscore, which captures the ability to accurately process emotions at a higher level of cognition and measures the ability to reason about and manage emotions and use them appropriately in social situations (Mayer et al., 2006).

Image Acquisition

Participant scans were obtained from a single site but two different scanners. Scanner type was accounted for in the analyses by including it as a covariate. Fifteen depressed and fifteen healthy controls were scanned using a neuro-optimized 3T Siemens scanner (Siemens AG) with a 12-channel head coil, referred to in this paper as scanner 1. Ten depressed and ten healthy controls were scanned using a 3T Philips scanner (Intera, Philips Medical System) with a SENSE parallel imaging head coil, referred to as scanner 2. Two depressed patients from scanner 1, two depressed patients from scanner 2, and four control subjects from scanner 2 were excluded from the study due to unavailability of scans or bad functional images. A total of 42 functional images were included in this report (21 depressed and 21 healthy controls).

T2*-weighted echo-planar images were acquired on scanner 1 with the following parameters: 272 volumes, repetition time 2410ms, echo time 35ms, flip angle 90o, field of view 192mm, matrix size 64 x 64, voxel size 3 x 3 x 3mm3, and 36 slices. T2*-weighted echo-planar images were acquired on scanner 2 with the following parameters: 400 volumes, repetition time 1650ms, echo time 30ms, field of view 211mm, matrix size 64 x 64, voxel size 3.3 x 3.3 x 3.25mm3, and 32 slices. The scanning duration for all images was approximately 11min. Participants were asked to lie still, keep their eyes open, and not to fall asleep.

Data Preprocessing

All resting-state fMRIs were preprocessed using FMRIB Software Library (FSL) version 4.1.9. The following preprocessing steps were applied using FMRI Expert Analysis Tool (FEAT) version 5.98: non-brain removal, motion correction using MCFLIRT (Jenkinson et al., 2002), slice timing correction using sinc interpolation, spatial smoothing with a Gaussian kernel (full width at half maximum = 8mm), and grand mean intensity normalization of the entire 4D dataset by a single multiplicative factor. In addition, the images were high–pass filtered to remove frequencies below 0.01 Hz. Signals from white matter, CSF, and the global signal were used as nuisance regressors to control for non-neuronal activation. The six motion parameters, three translations, and three rotations estimated by MCFLIRT were also regressed to account for any remaining effects of motion. The images were also temporally bandpass filtered (0.01–0.08 Hz) to limit the analysis to the low frequency fluctuations. No participant had excessive motion (>3mm): maximum translation or degree rotation was 2mm for participants from scanner one and 2.5mm for participants from scanner two.

Statistical Analyses

Seed-Based Functional Connectivity

A whole brain seed–based functional connectivity analysis was carried out on the resting-state functional images to investigate differences in functional connectivity maps of each region of interest (ROI) between depressed and healthy subjects. For each of the four ROIs, two spheres were defined bilaterally using the Wake Forest University Pickaltas software (www.ansir.wfubmc.edu). The center of each ROI was specified with the coordinates x, y, and z in Montreal Neurological Institute (MNI) space: BA25 at ±5, 26, and -10; BA10m at ±5, 34, and -18; BA10r at ±5, 46, and -14; and BA10p at ±5, 60, and 4, respectively. A 3.5mm radius was specified for the BA25, BA10m, and BA10r spheres and a 5mm radius was specified for the BA10p spheres (Figure 1B). The ROIs correspond to the structural division of the subgenual ACC and BA10 (Ongur et al., 2003). The seeds were transformed from MNI space to the subjects’ native space by using the inverse transformation matrix created from the registration of the functional images to their respective structural images and standard space MNI (as done in Pannekoek et al., 2013). The mean time series of each seed was extracted and used as a regressor in a general linear model to create a functional connectivity map of each seed for each subject in its native space.

The functional connectivity maps of all subjects in MNI space were carried to a second-level mixed-effects analysis. Four contrasts were included in the GLM: depressed group’s mean connectivity, control group’s mean connectivity, greater connectivity in the depressed group (depressed > controls), and greater connectivity in the control group (controls > depressed). Each seed was analyzed separately. Age and type of scanner were included as covariates to control for any effect of age and scanner parameters. All statistical maps were thresholded at Z > 2.3 with a cluster-corrected significance threshold of p < 0.05, using random field analysis. If the whole brain analyses did not reveal a significant group difference, the analysis was repeated using a mask of each group’s mean FC map (depressed group mean FC + control group mean FC) to limit the number of voxelwise comparisons (as noted in the Results).

Exploratory Analyses of vmPFC FC and Emotional Intelligence

Permutation-based non-parametric statistics were carried out using Randomise with the generation of 5000 permutations to investigate the relationship between functional connectivity of the BA25 and BA10p seeds and emotional intelligence (Nichols and Holmes, 2002). Non-parametric statistics were used due to the robustness of these tests with non-normal data. The main effect of the MSCEIT total score was investigated, using IDS as a covariant, to control for the effect of depression severity on the relationship between emotional intelligence and functional connectivity. If the results were significant, scores on the MSCEIT subscales (Experiential Emotional Intelligence and Strategic Emotional Intelligence) were investigated to further understand the relationship between emotional intelligence and FC. Moreover, group by MSCEIT score interactions were run to determine whether the relationship between emotional intelligence and FC differed between depressed and healthy control groups. Analyses were carried out using a mask of each group’s mean FC map. Statistical thresholds were obtained using threshold-free cluster enhancement (TFCE).

Voxelbased Morphometry Analyses

Gray matter volume of the four ROIs were compared between the depressed and healthy controls using voxelbased morphometry techniques to rule out group differences in grey matter integrity. The participants’ structural images were segmented, averaged, and non-linearly registered to a grey matter template. Permutation-based non-parametric statistics were then applied to calculate group difference in grey matter density in the BA25, BA10m, BA10r, and BA10p seeds.

Results

Demographics

The participants were between 22 and 61 years old. The racial makeup of the sample was 67% (n = 42) white, 26% African American, 5% Asian, and 2% American Indian. The depressed and control groups did not significantly differ in age or gender distribution. The groups differed on years of education after high school, IDS-SR and Hamilton scores, and on the Seek, Fear, Anger, Play, and Sadness subscores of the Affective Neuroscience Personality Scale (see Table 1). Wilcoxon rank sum tests were used for the group comparisons due to non-normality of the data and Chi squared tests were used for group comparison of gender.

Table 1.

Demographics and Test Scores

| MDD (n = 21) | Controls (n = 21) | W/X 2 | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | |||

| Age | 37.29 (14.22) | 38.33 (12.92) | 212 | 0.84 |

| Gender (F/M) | 17/4 | 17/4 | 0 | 1 |

| Education | 3.57 (2.48) | 6.62 (3.49) | 82.5 | 0.0004 |

| IDS-SR | 32.43 (10.97) | 4.6 (3.22) | 420 | <0.0001 |

| HRSD | 23.29 (6.46) | 2.14 (2.08) | 441 | <0.0001 |

| STAI-Y2 | 54.95 (9.75) | 27.05 (4.87) | 420 | <0.0001 |

| EQ | 40.71 (10.77) | 49.57 (12.06) | 130.5 | 0.02 |

| ANPS seek | 21.95 (5.1) | 26.81 (4.12) | 102 | 0.003 |

| ANPS fear | 26.38 (7.62) | 16.67 (5.05) | 386.5 | <0.0001 |

| ANPS care | 25.14 (4.68) | 26.95 (7.45) | 197.5 | 0.57 |

| ANPS anger | 22 (6.65) | 16.71 (5.09) | 342.5 | 0.002 |

| ANPS play | 19.67 (5.96) | 27.81 (6.87) | 79.5 | 0.0004 |

| ANPS sadness | 25.05 (4.92) | 16.71 (2.26) | 415.5 | <0.0001 |

| ANPS spirituality | 18.81 (7.1) | 22.14 (5.8) | 150.5 | 0.08 |

| MSCEIT total score | 95.06 (15) | 107.99 (10.03) | 100 | 0.003 |

| MSCEIT experiential emotional intelligence | 98.41 (16.76) | 113.07 (9.66) | 93 | 0.001 |

| MSCEIT strategic emotional intelligence | 94.03 (10.4) | 100.76 (9.9) | 132 | 0.067 |

Education is shown as years post–high school.

ANPS, Affective Neuroscience Personality Scale (subscale dimensions include: seeking, fear, care, anger, playfulness, sadness, spirituality); EQ, Empathy Quotient; F, female; HRSD, Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression; IDS-SR, Inventory of Depressive Symptoms–Self Report; M, male; MDD, major depressive disorder; MSCEIT, Mayer-Salovey-Caruso Emotional Intelligence Test (subscales include: Experiential and Strategic Emotional Intelligence); SD, standard deviation; STAI-Y2, State and Trait Anxiety Inventory–Y2; W/X 2, Wilcoxon rank sum tests and chi-square tests.

Seed-Based Functional Connectivity

BA10p Seed

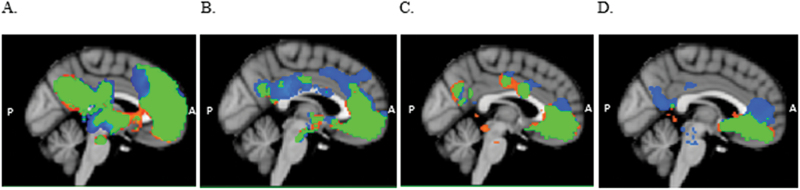

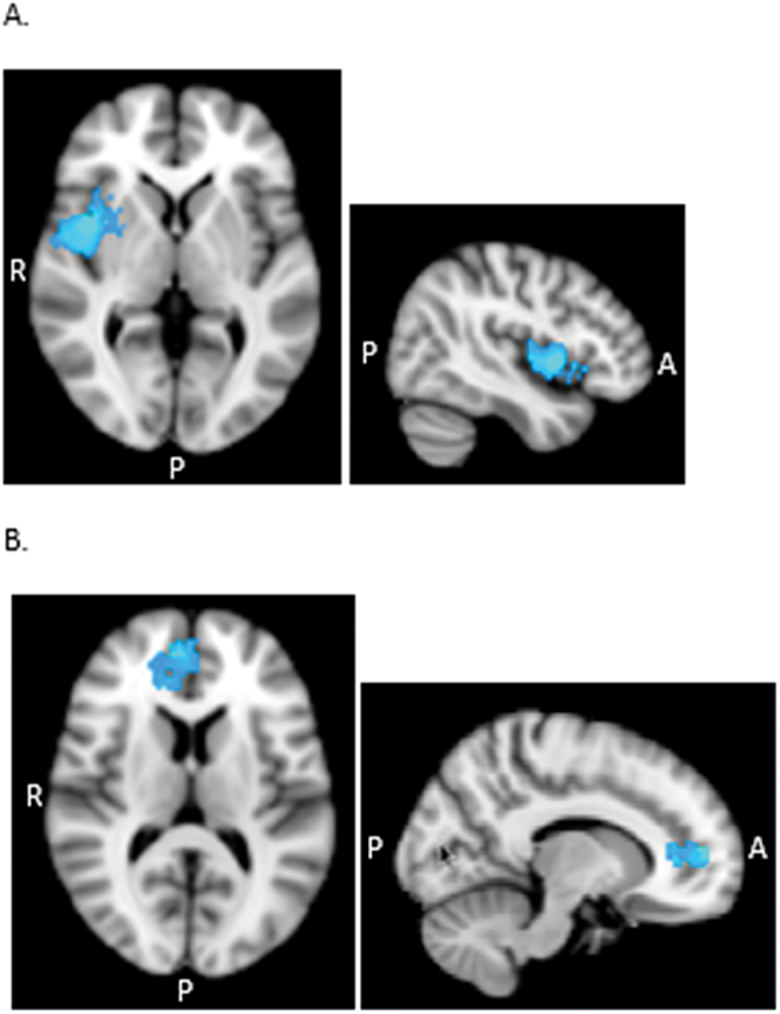

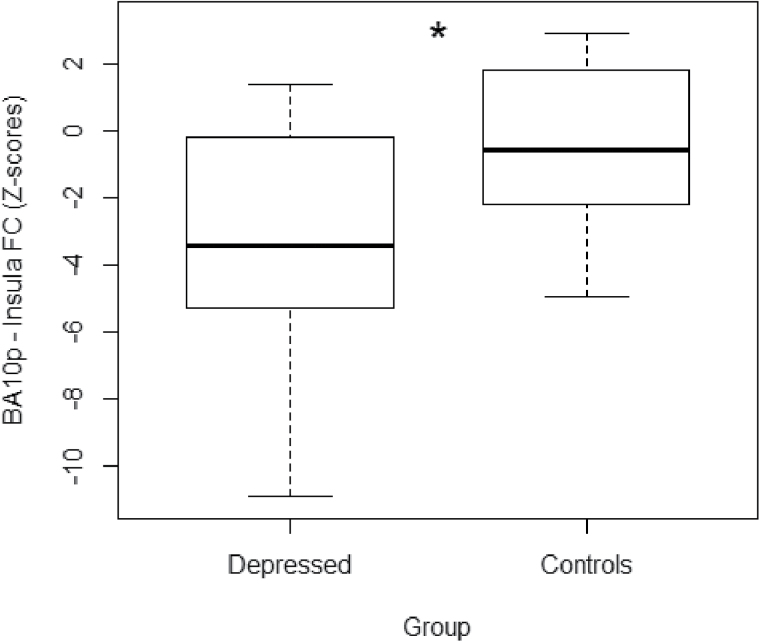

FC maps of the BA10p seed were similar in the depressed and control groups, encompassing regions of the DMN that included the ventromedial PFC, dorsal ACC, superior frontal gyrus, PCC, precuneus and angular gyrus, and subcortical regions, including the thalamus, caudate, and putamen (see Figure 2A). The healthy control FC map, however, extended further dorsally compared to the depressed map, additionally encompassing the dorsal part of BA32 and BA8 as well as extending laterally to include the insular cortex bilaterally (Table 2). Results from the whole-brain mixed-effects analysis showed the controls to have significantly greater connectivity of the BA10p seed with the right insula (Z > 2.3, p < 0.05 cluster corrected; Figure 3A). The depressed group did not show any region of greater connectivity compared to the controls (p > 0.05) in whole-brain and mask-restricted analyses. Extraction of the individual subject’s mean connectivity in the insula cluster showed that the depressed group had a more negative BA10p insula FC compared to the control group (Figure 4).

Figure 2.

Mean functional connectivity maps (Z > 2.3, p < 0.05 cluster corrected) for BA10p (A), BA10r (B), BA10m (C), and BA25 (D) seeds, for depressed patients (orange) and healthy controls (blue). Overlapping areas between the two groups are depicted in green. The functional connectivity (FC) maps consist of default mode network regions. Results show a significant group difference in the spatial extent of the FC maps in A and D. BA, Brodmann areas.

Table 2.

Seed Functional Connectivity Maps

| Seed | Regions exhibiting significant connectivity | BA | Cluster size (voxels) | MNI coordinates of peak voxel (x, y, z) | Z-value (peak) | p (peak voxel) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BA10p | |||||||

| D | Frontal pole extending to medial & superior frontal gyrus, ACC, angular gyrus, superior temporal gyrus, PCC, precuneus, thalamus, putamen, nucleus accumbens | 10, 9, 8, 32, 24, 39, 22, 23, 31 | 29209 | 4, 60, 4 | 10.7 | <0.001 | |

| C | Frontal pole extending to medial & superior frontal gyrus, ACC, angular gyrus, superior temporal gyrus, PCC, precuneus, insula, thalamus, putamen, nucleus accumbens | 10, 9, 8, 6, 32, 24, 39, 22, 23, 31, 47, 13 | 31495 | 4, 60, 4 | 10.8 | <0.001 | |

| D > C | - | - | - | - | - | ns | |

| C > D | right insular cortex | 13 | 878 | 44, 6, 2 | 4.32 | 0.041 | |

| BA10r | D | Medial frontal cortex extending to perigenual ACC, precuneus, superior temporal gyrus | 10r, 32, 24, 28, 34, 30 | 11208 | 4, 46, -14 | 11.6 | <0.001 |

| C | Medial frontal cortex extending to perigenual ACC, dorsal ACC, precuneus, superior temporal gyrus | 10r, 24, 32, 24a’/b’/c’, 32’, 31, 28, 34, 30 | 14107 | 4, 46, -14 | 11.3 | <0.001 | |

| D > C | - | - | - | - | - | ns | |

| C > D | - | - | - | - | - | ns | |

| BA10m | D | Medial frontal cortex extending to perigenual ACC, dorsal ACC, precuneus, left temporal pole | 10m, 24, 24a’/b’/c’, 31, 38 |

14953 | 0, 34, -18 | 11.6 | <0.001 |

| C | Medial frontal cortex extending to perigenual ACC, dorsal ACC, precuneus | 10m, 24, 32, 24a’/b’/c’, 31 | 10398 | 0, 34, -18 | 11.4 | <0.001 | |

| D > C | - | - | - | - | - | ns | |

| C > D | - | - | - | - | - | ns | |

| BA25 | D | subcallosal cortex, frontal pole | 33, 32, 10 | 9495 | -2, 26, -10 | 11.3 | <0.001 |

| C | subcallosal cortex, perigenual ACC, frontal pole, precuneus | 33, 32, 24, 10, 31 | 9441 | -2, 26, -10 | 11.3 | <0.001 | |

| D > C | - | - | - | - | - | ns | |

| C > D | Frontal pole, perigenual ACC | 10, 32, 24c | 663 | 12, 52, 10 | 4.34 | 0.017 |

Regions exhibiting significant functional connectivity (FC) with the seeds represent regions with maximum Z value extending to other brain regions with significant FC, for the depressed and healthy control groups. Results of mixed-effects analyses show the difference in FC between the two groups. Refer to Pizagalli (2011) for Brodmann areas.

ACC, anterior cingulate cortex; BA, Brodmann areas; C, control group; D, depressed group; MNI; PCC, posterior cingulate cortex.

Figure 3.

Axial and sagittal views displaying significant group differences for BA10p (A) and BA25 (B) seed regions. (A) Greater functional connectivity (FC) of BA10p with the right insula in the controls compared to the depressed patients (C > D) in the whole brain analysis. (B) Greater FC of BA25 with a region covering BA24, BA32, and BA10p in the controls compared to the depressed patients (C > D) in the mask-restricted analysis. All statistical analyses were thresholded at Z > 2.3, p < 0.05 cluster corrected. BA, Brodmann areas; C, control group; D, depressed group.

Figure 4.

Boxplots showing mean functional connectivity (FC) of Brodmann area 10p with the right insula for each group. Z-scores from the significant insula cluster were extracted for each participant. Both groups showed a mean negative FC between the two regions, with the controls showing a significantly more positive FC compared to the depressed subjects. *Z = 2.3, p < 0.05 cluster corrected.

BA10r Seed

FC maps of the BA10r seed were similar in the depressed and control groups, including the ACC, vmPFC, frontal pole and the PCC (Figure 2B). The control FC map covered additional regions along the superior frontal gyrus (BA9) and the PCC. Group comparisons did not reveal significant differences between the groups’ BA10r FC map even after restricting the number of voxel-wise comparisons.

BA10m Seed

FC maps of the BA10m seed were similar in both groups and included the subgenual ACC, vmPFC, frontal pole, and PCC (Figure 2C). Group comparisons revealed no significant differences between the groups’ BA10m FC maps even after restricting the number of voxel-wise comparisons.

BA25 Seed

FC maps of the subgenual ACC seed were similar in the two groups, encompassing the subcallocal cortex, ACC, and frontal medial cortex (including BA10m and BA10r). The control subjects’ maps, however, extended to the dorsal regions of the ACC, covering BA32ac and the dorsal region of BA10p as well as the posterior cingulate gyrus (Figure 2D). The depressed subjects’ maps showed additional correlations with the lateral occipital cortex. Whole-brain analyses did not reveal any group difference, but when the mask was included, results showed significantly greater connectivity in the control group between BA25 and a region overlaying BA32ac, BA24a’/b’, and BA24b/c (Z > 2.3, p < 0.05 cluster corrected; Figure 3B). The depressed group did not reveal any region of significantly greater connectivity compared to the control group (p > 0.05) in whole-brain and mask-restricted analyses.

Voxelbased Morphometry Analysis

No group difference was found in any of the ROIs (p > 0.05, TFCE corrected).

Exploratory Analyses

MSCEIT Total Score

Analysis of the main effect of the MSCEIT total score on BA25 functional connectivity, after covarying for IDS, showed a significant positive relationship between emotional intelligence and BA25–BA24 connectivity (p < 0.05, TFCE corrected). Analysis of the main effect of MSCEIT total score on BA10p FC revealed no significant relationship between the two (p > 0.05). Analysis of the relationship between BA25 FC and MSCEIT subscores were therefore carried out.

MSCEIT Experiential Emotional Intelligence Subscale

The main effect of the Experiential Emotional Intelligence score, covarying for IDS, showed a significant positive relationship of BA25 FC with BA24 (p < 0.05, TFCE corrected; Figure 5; see Supplementary Material Figure S1). There was no significant interaction with group in predicting BA25 FC (p > 0.05).

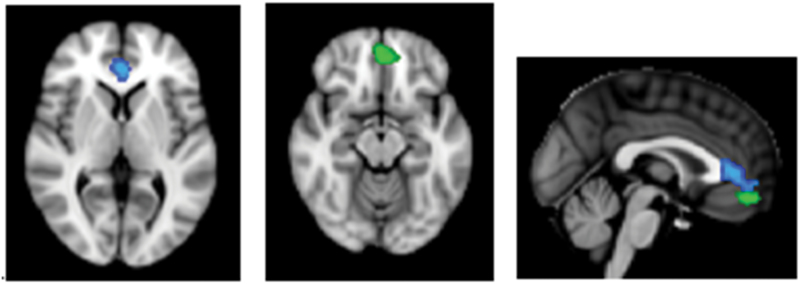

Figure 5.

Axial and sagittal views displaying the regions with a significant relationship between emotional intelligence and BA25 functional connectivity. Green indicates the BA10r cluster. There was a significant group difference in the relationship between Strategic Emotional Intelligence and BA25 functional connectivity (FC) in a BA10r cluster. Cluster size = 208 voxels, peak value at x = -2, y = 46, z = -14 MNI, p = 0.01. Blue indicates the BA24 cluster. There was a significant relationship between Experiential Emotional Intelligence and BA25 FC in a BA24 cluster in the whole sample. Cluster size = 460 voxels, peak value at x = 0, y = 38, z = 4 MNI space, p = 0.016. BA, Brodmann areas.

MSCEIT Strategic Emotional Intelligence Subscale

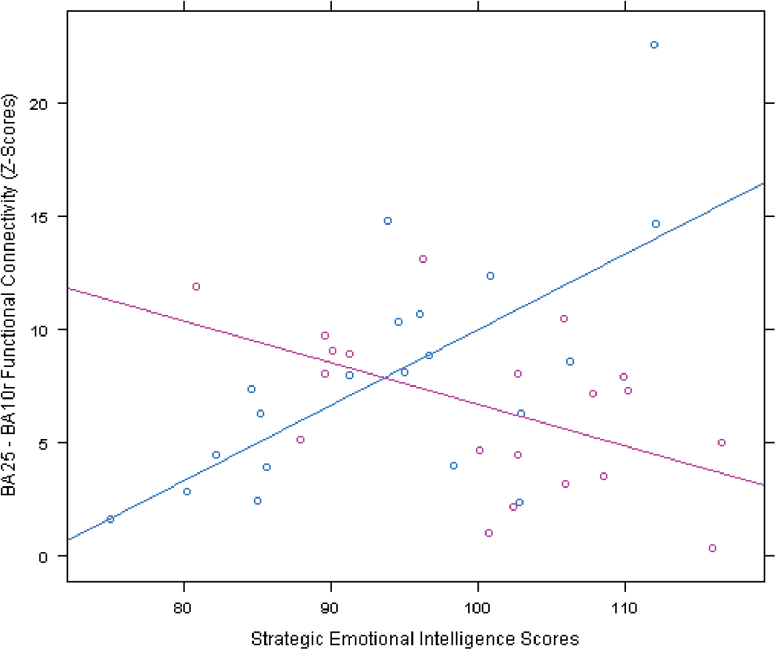

The main effect of the Strategic Emotional Intelligence score in predicting BA25 FC, covarying for IDS, was not significant (p > 0.05). There was, however, a significant interaction with group in a region overlaying BA10r (p < 0.05, TFCE corrected; Figure 5). Analysis of each group separately revealed that there was a positive correlation between Strategic Emotional Intelligence and BA25–BA10r FC for the depressed group and a negative correlation for the control group (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

This figure displays the significant interaction between group and Strategic Emotional Intelligence in predicting BA25 functional connectivity (FC). In a cluster encompassing BA10r, the depressed group (blue) showed a positive relationship between Strategic Emotional Intelligence and BA25 FC and the control group (pink) showed a negative relationship between strategic emotional intelligence and BA25 FC. Mean Z-scores, representing BA25–BA10r FC, were extracted from the BA10r cluster for each participant.

BA, Brodmann areas.

Discussion

Although the anatomical subdivision of the anterior PFC has been established in the human and non-human primate brain, connectivity analyses have not distinguished between the sub-regions of the anterior and middle PFC. To our knowledge, this is the first study to explore the specific sub-anatomic functional connectivity maps of BA10 subregions in depressed patients. Visual inspection of the FC maps showed that seed regions farthest from the subcallosal area (i.e. seeds located more anteriorly) connected to more dorsal and posterior brain areas. Statistical analyses of group differences on FC maps showed that compared to controls, depressed subjects had significantly reduced connectivity between regions of the anterior DMN and areas involved in emotional regulation. Additionally, this study reports on the relationship between vmPFC FC and emotional intelligence.

The finding of reduced FC between the subgenual ACC and the perigenual ACC in depressed subjects could explain the disturbances in mood, sleep, and emotional regulation in MDD. The subgenual ACC is involved in the modulation of autonomic responses during affective processing and the perigenual ACC is involved in integrating mood, sleep, and autonomic and cognitive processes (Mayberg, 1997). Studies have also shown that metabolism in the perigenual ACC and connectivity with limbic and paralimbic regions are predictive of treatment response (Mayberg, 1997; Anand et al., 2005; Pizzagalli, 2011; Rentzsch et al., 2013). Data from cognitive and neuroimaging studies support the dichotomy between the subgenual and perigenual vmPFC regions, the former being associated with negative affect and the latter with positive affect (Myers-Schultz and Koenigs, 2012). Reduced FC between the subgenual and perigenual ACC can therefore be a vulnerability factor that makes individuals more susceptible to depression or makes it more difficult to exit a depressive state (Holtzheimer and Mayberg, 2011).

The finding of reduced FC between the BA10p seed and the right anterior insular cortex in the depressed group replicated studies that reported reduced FC between the insula and regions of the DMN (Veer et al., 2010; Hamilton et al., 2011). During rest, BA10p is activated as part of the DMN, which undertakes internal-state processing such as self-referential thinking. The insular cortex, an integral part of the affective salience network, is involved in the awareness of autonomic sensations and arousing stimuli (Sliz and Hayley, 2012) and the mapping of visceral and somatic representations that guide reward-based decision-making ability (Bechara and Damasio, 2005). Reduced FC between BA10p and the insula could indicate impaired integration of physiologic signals with introspective thoughts, resulting in reduced awareness of sensations and, ultimately, reduced ability to regulate emotion.

The insular cortex is also involved in goal-directed thinking that is important for a wide range of cognitive and emotional processes (Chang et al., 2013). With its extensive connections to prefrontal regions, the anterior insula has been shown to be directly involved in switching between the DMN and central executive networks to shift the brain’s resources from internal processing to the processing of externally salient stimuli (Menon and Uddin, 2010). The finding of reduced BA10p insula FC could therefore also indicate a fundamental abnormality in the connectivity between two brain networks required for the coordination of information during processing of cognitive and emotional stimuli, as well as related internal states. Studies on neurological patients have shown a direct causal relationship between the integrity of the salience network and activity within the DMN (Bonnelle et al., 2012; Chiong et al., 2013).

Results of the exploratory analysis showed that even after controlling for depression severity, the basic ability to feel and perceive emotions was positively related to FC between the subgenual and perigenual ACC. This finding suggests that accurate perception and identification of emotions in oneself and others is dependent on intact functional coherence between regions involved in the modulation of autonomic responses (Freedman et al., 2000) and emotional tagging of stimuli (Pizzagalli, 2011). The ability to process emotions at a higher level of cognition was shown to be positively related to subgenual ACC BA10r FC in depressed subjects and negatively related to it in control subjects. One plausible explanation for this finding is that in a depressed state, failure to adequately recruit anterior prefrontal brain regions hinders one’s ability to use cognitive resources needed to manage one’s emotions. The literature provides evidence for reduced FC (Takeuchi et al., 2013) and smaller grey matter volume (Killgore et al., 2012) in regions of the DMN and salience network in participants with low emotional intelligence scores. Results from the present study show no evidence of a relationship between BA10p connectivity and emotional intelligence. It is surprising that BA10p insular connectivity was not significantly related to the MSCEIT scores, since that region has been implicated in emotional intelligence.

Limitations and Future Directions

Participants included in this study were scanned using two different scanners, although this was statistically controlled for in the analyses. Another limitation is the group difference in education level. It is unlikely, however, that the group differences in emotional intelligence were driven by different levels of education, for two reasons: (1) both groups had several years of education after high school and (2) group remained a significant predictor of MSCEIT scores even after covarying for education (see Supplementary Material Figure S2). It is possible that ROI size affected the probability of finding a significant group difference in FC. Small ROIs might not capture enough of the variance in the signal of a region, thereby increasing the probability of a false negative. Moreover, caution must be taken when interpreting fMRI data from the subgenual ACC region, since this region is subjected to signal drop. Inspection of individual scans, however, reveals no group difference in the number of scans with signal dropout. Another limitation is the application of global signal regression to the functional images, which could have induced the negative correlations observed. The importance of using global signal regression in preprocessing functional images is, however, emphasized in resting-state fMRI studies (Fox et al., 2009).

Conclusion

These results suggest that, even in a sample of non–treatment resistant depressed patients, regions of the anterior DMN fail to adequately connect to emotional regulatory regions during a state of rest. Disrupted FC between those regions could reduce the individual’s ability to recognize their own and others’ emotions, consequently diminishing their capacity to engage in positively reinforcing social interactions, thus further promoting depressive states. Future studies are needed to conclude whether these deficits are state- or trait-dependent.

Supplementary Material

For supplementary material accompanying this paper, visit http://www.ijnp.oxfordjournals.org/

Statement of Interest

Recent lectures were sponsored by Magventure, Eli Lilly, and Pfizer. None of the institutions providing grants played a role in the design, analyses, or writing of this report.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by grants from the National Institute of Mental Health, the Brain and Behavior Research Foundation (formally known as National Alliance of Research on Schizophrenia and Depression), the Hope for Depression Research Foundation, American University of Beirut’s Intramural Funds, Medtronic Inc., Massachusetts Emergency Care Training Academy, Pfizer, and Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique.

References

- American Psychiatric Association (2000). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (4th edition). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press. [Google Scholar]

- Anand A, Li Y, Wang Y, Wu J, Gao S, Bukhari L. (2005). Activity and connectivity of brain mood regulating circuit in depression: a functional magnetic resonance study. Biol Psychiatry 57:1079–1088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bechara A, Damasio AR. (2005). The somatic marker hypothesis: A neural theory of economic decision. Game Econ Behav 52:336–372. [Google Scholar]

- Bonnelle V, Hama TE, Leech R, Kinnunen KM, Mehta MA, Greenwood R. (2012). Salience network integrity predicts default mode network function after traumatic brain injury. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 109:4690–4695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourke C, Douglas K, Porter R. (2010). Processing of facial emotion expressions in major depression: a review. Aus New Zeal J Psychiatry 44:681–696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao X, Liu Z, Xu C, Li J, Gao Q, Sun N, Xu Y, Ren Y, Yang C, Zhang K. (2012). Disrupted resting-state functional connectivity of the hippocampus in medication-naïve patients with major depressive disorder. J Affect Disord 141:194–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang LJ, Yarkoni T, Khaw MW, Sanfey AG. (2013). Decoding the role of the insula in human cognition: functional parcellation and large-scale reverse inference. Cereb Cortex 23:739–749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiong W, Wilson SM, D’ Esposito M, Kayser AS, Grossman SN, Poorzand P. (2013). The salience network causally influences default mode network activity during moral reasoning. Brain 136:1929–1941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Damasio AR. (1996). The somatic marker hypothesis and the possible functions of the prefrontal cortex. Phil Trans R Soc B 351:1413–1420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis KL, Panksepp J. (2011). The brain’s emotional foundations of human personality and the affective neuroscience personality scales. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 35:1946–1958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Downey LA, Johnston PJ, Hansen K, Schembri R, Stough C, Tuckwell V, Schweitzer I. (2008). The relationship between Emotional intelligence and depression in a clinical sample. Eur J Psychiat 22:93–98. [Google Scholar]

- First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW. (1996). Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders, Clinician Version (SCID-CV). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Fitzgerald PB, Laird AR, Maller J, Daskalakis ZJ. (2008). A meta-analytic study of changes in brain activation in depression. Hum Brain Mapp 29:683–695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox MD, Zhang D, Snyder AZ, Raichle ME. (2009). The global signal and observed anticorrelated resting state brain networks. J Neurophysiol 101:3270–3283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freedman LJ, Insel TR, Smith Y. (2000). Subcortical projections of area 25 (subgenual cortex) of the macaque monkey. J Comp Neurol 421:172–188. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greicius MD, Flores BH, Menon V, Glover GH, Solvason HB, Kenna H, Reiss AL, Schatzberg AF. (2007). Resting-state functional connectivity in major depression: Abnormally increased contributions from subgenual cingulate cortex and thalamus. Biol Psychiatry 62:429–437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton JP, Furman DJ, Chang C, Thomason ME, Dennis E, Gotlib IH. (2011). Default-mode and task-positive network activity in major depressive disorder: implications for adaptive and maladaptive rumination. Biol Psychiatry 70:327–333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holtzheimer PE, Mayberg HS. (2011). Deep brain stimulation for psychiatric disorders. Annu Rev Neurosci 34:289–307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenkinson M, Bannister P, Brady JM, Smith SM. (2002). Improved optimisation for the robust and accurate linear registration and motion correction of brain images. NeuroImage 17:825–841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Killgore WDS, Weber M, Schwab ZJ, DelDonno SR, Kipman M, Weiner MR, Rauch SL. (2012). Gray matter correlates of Trait and Ability models of emotional intelligence. Neuroreport 23:551–555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwako LE, Szanton SJ, Saligan LN, Gill JM. (2011). Major depressive disorder in persons exposed to trauma: relationship between emotional intelligence and social support. J Am Psychiatr Nurses Assoc 17:237–245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence EJ, Shaw P, Baker D, Baron-Cohen S, David AS. (2004). Measuring empathy: reliability and validity of the empathy quotient. Psychol Med 34:911–924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li B, Liu L, Friston KJ, Shen H, Wang L, Zeng LL, Hu D. (2013). A treatment resistant default mode subnetwork in major depression. Biol Psychiatry 74:48–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu L, Zeng LL, Li Y, Ma Q, Li B, Shen H, Hu D. (2012). Altered cerebellar functional connectivity with intrinsic connectivity networks in adults with major depressive disorder. PLOS ONE 7:e39516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lloyd SJ, Malek-Ahmadi M, Barclay K, Fernandez MR, Chartrand MS. (2012). Emotional intelligence (EI) as a predictor of depression status in older adults. Arch Gerontol Geriatr 55:570–573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mah LWY, Arnold MC, Grafman J. (2005). Deficits in social knowledge following damage to ventromedial prefrontal cortex. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 17:66–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayberg HS. (1997). Limbic-cortical dysregulation: A proposed model of depression. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 9:471–481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayberg HS, Liotti M, Brannan SK, McGinnis S, Mahurin RK, Jerabek PA. (1999). Reciprocal limbic-cortical function and negative mood: converging PET findings in depression and normal sadness. Am J Psych 156:675–682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayer JD, Salovey P, Caruso DR. (2006). MSCEIT: Mayer-Salovey-Caruso Emotional Intelligence Test. Toronto, ON: Multi-Health Systems, Inc. Retrieved 22 Jan 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Menon V, Uddin LQ. (2010). Saliency, switching, attention and control: a network model of insula function. Brain Struct Funct 214:655–667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myers-Schultz B, Koenings M. (2012). Functional anatomy of ventromedial prefrontal cortex: implications for mood and anxiety disorders. Mol Psychiatry 17:132–141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nichols E, Holmes AP. (2002). Nonparametric permutation tests for functional neuroimaging: A primer with examples. Hum Brain Mapp 15:1–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ongur D, Ferry AT, Price JL. (2003). Architectonic subdivision of the human orbital and medial prefrontal cortex. J Comp Neurol 460:425–449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pannekoek JN, Veer IM, van Tol MJ, van der Werff SJA, Demenescu LR, Aleman A, Veltman DJ, Zitman FG, Rombouts SARB, van der Wee NJA. (2013). Aberrant limbic and salience network resting-state functional connectivity in panic disorder without comorbidity. J Affect Disord 145:29–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pizzagalli DA. (2011). Frotocingulate dysfunction in depression: toward biomarkers of treatment response. Neuropsychopharmacology 36:183–206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price JL, Drevets WC. (2010). Neurocircuitry of mood disorders. Neuropsychopharmacology 35:192–216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rentzsch J, Adli M, Wiethoff K, Gómez-Carrillo de Castro A, Gallinat J. (2014). Pretreatment anterior cingulate activity predicts antidepressant treatment response in major depressive episodes. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 264:213–223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rolls ET. (2014). Emotion and Decision Making Explained. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rush AJ, Gullion CM, Basco MR, Jarrett RB, Trivedi MH. (1996). The Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology (IDS): Psychometric properties. Psychol Med 26:477–486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sackeim HA, Pudric J, Devanand DP, Decina P, Kerr B, Malitz S. (1990). The impact of medication resistance and continuation pharmacotherapy on relapse following response to electroconvulsive therapy in major depression. J Clin Psychopharmacol 10:96–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salguero JM, Extremera N, Fernandez-Berrocal P. (2012). Emotional intelligence and depression: The moderator role of gender. Pers Individ Dif 53:29–32. [Google Scholar]

- Sambarto F, Wolf ND, Pennuto M, Vasic N, Wolf RC. (2013). Revisiting default mode network function in major depression: evidence for disrupted subsystem connectivity. Psychol Med. Advance online publication. Retrieved X. 10.1017/S0033291713002596 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sliz D, Hayley S. (2012). Major depressive disorder and alterations in insular cortical activity: a review of current functional magnetic imaging research. Front Hum Neurosci 6:1–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith SM, Miller KL, Moeller S, Xu J, Auerbachb EJ, Woolric MW, Beckmann CF, Jenkinson M, Andersson J, Glasser MF, Van Essen DC, Feinberg DA, Yacoub ES, Ugurbil K. (2012). Temporally-independent functional modes of spontaneous brain activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 109:3131–3136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spielberger CD. (1983). Manual for the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory: STAI (Form Y). Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press. [Google Scholar]

- Takeuchi H, Taki Y, Nouchi R, Sekiguchi A, Hashizume H, Sassa Y. (2013). Resting state functional connectivity associated with trait emotional intelligence. Neuroimage 83:318–328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veer IM, Beckmann CF, van Tol MJ, Ferrarini L, Milles J, Veltman DJ. (2010). Whole brain resting-state analysis reveals decreased functional connectivity in major depression. Front Syst Neurosci 4:1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu D, Yuan Y, Bai F, You J, Li L, Zhang Z. (2013). Abnormal functional connectivity of the default mode network in remitted late-onset depression. J Affect Disord 147:277–287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Y, Yu C, Zheng H, Liu Y, Song M, Qin W, Li K, Jiang T. (2010). Increased neural resources recruitment in the intrinsic organization in major depression. J Affect Disord 121:220–230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu X, Wang X, Xiao J, Liao J, Zhong M, Wang W, Yao S. (2012). Evidence of a dissociation pattern in resting-state default mode network connectivity in first-episode, treatment-naive major depression patients. Biol Psychiatry 71:611–617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.