Abstract

Dissociated cell cultures of the rodent hippocampus have become a standard model for studying many facets of neural development. The cultures are quite homogeneous and it is relatively easy to express green fluorescent protein (GFP)-tagged proteins by transfection. Because the cultures are essentially two dimensional, there is no need to acquire images at multiple focal planes. For capturing rapid subcellular events at high resolution, as described here, one must maximize weak signals and reduce background fluorescence. Thus, these methods differ in several respects from those used for time-lapse imaging. Lipofectamine-mediated transfection yields a higher level of expression than does transfection with a nucleofection device. Images are usually collected with a spinning-disk confocal microscope, which improves the signal-to-noise ratio. In addition, we use an imaging medium designed to minimize background fluorescence rather than to enhance long-term cell survival. It is also important to select cultures at an appropriate stage of development. In our hands, lipofectamine-based transfection works best on cells between 3 and 10 d after plating. GFP-based fluorescence can be observed as early as 4 h after adding the DNA/lipid complexes to the cells, but expression usually increases over the next ~12 h and remains steady for days. The ratio of DNA to lipid is critical; to lower expression levels of the tagged construct, we use a combination of expression vector and empty plasmid, keeping the DNA amount constant. An example is included to illustrate the imaging of the microtubule-based vesicular transport of membrane proteins.

MATERIALS

It is essential that you consult the appropriate Material Safety Data Sheets and your institution’s Environmental Health and Safety Office for proper handling of equipment and hazardous materials used in this protocol.

Reagents

Glial cell culture

Lipofectamine 2000

Mounting solution: HEPES-buffered saline with 0.6% (w/v) glucose or Hibernate E with low fluorescence (BrainBits LLC, Springfield, IL)

Neuronal cell cultures to be transfected

Plasmid DNA for expression of GFP-tagged proteins (a single plasmid species or a combination of plasmids)

Serum-free medium

Silicon grease

Equipment

Fine forceps

Imaging setup, including imaging chamber with temperature control (for details, see General Considerations for Live Imaging of Developing Hippocampal Neurons in Culture [Kaech et al. 2012a])

Microcentrifuge tubes

METHOD

Methods for establishing hippocampal cultures—including preparation of coverslips, generation of glial cultures, and hippocampal dissection and dissociation of neurons from embryonic tissue—are described in detail in a recent protocol (Kaech and Banker 2006) available for download on our website (http://www.ohsu.edu/xd/research/centers-institutes/neurology/jungers-center/research/banker-lab.cfm). General information is also available in General Considerations for Live Imaging of Developing Hippocampal Neurons in Culture (Kaech et al. 2012a).

Labeling Cells by Lipid-Mediated Transfection

-

1

Working in a laminar flow hood, prepare the DNA/lipid complexes to be used for transfection.

Dilute 3–5-μL Lipofectamine 2000 into 100 μL of serum-free medium in a microcentrifuge tube.

Mix a total of 1–2.5 μg of plasmid DNA (from one or a combination of plasmids) into 100 μL of serum-free medium in a second microcentrifuge tube.

Allow the tubes to stand at room temperature for 5 min.

-

2

Combine the contents of the two tubes, and mix vigorously by pipetting with a micropipette. Incubate at room temperature for 30 min to allow DNA/lipid complexes to form.

-

3

Retrieve the neuronal culture dish from the incubator, and turn the coverslips so that the neurons face up.

-

4

Distribute DNA/lipid complexes dropwise onto the coverslips, and return the dish to the incubator.

-

5

After 90–120 min, remove the coverslips with transfected cells, and place them into a new dish. Based on the coculture method we use for culturing hippocampal neurons, we transfer the coverslips into a dish containing glia and flip them upside down again (with neurons facing the glial monolayer). Return the dish to the incubator.

Image Acquisition

-

6

Turn on microscope and objective heater.

-

7

Mount coverslips in an imaging chamber using either a HEPES-buffered saline or low-fluorescence Hibernate E.

-

8

Place the chamber on the microscope stage, and turn on the temperature control to begin heating the chamber.

-

9

Scan the coverslip for suitable cells for imaging. Because only a few cells may be transfected, this process can be tedious. To find labeled cells faster, it can be helpful to cotransfect with soluble GFP (or an appropriate color variant) to label the axons and dendrites so they can be followed back to the transfected cell.

A focus-stabilization device can be helpful when searching for transfected cells because it will maintain focus while scanning across large areas in which there is no fluorescence signal for focusing by eye. -

10

Set the imaging parameters, and acquire an image series.

See Troubleshooting.

TROUBLESHOOTING

Problem (Step 10)

The signal is too dim to capture an image using a short exposure. Obviously, for small dim structures, there is a limit to how fast one can acquire an image with an adequate signal-to-noise ratio. The goal is not to acquire an image of the highest quality but simply to obtain images in which the signal level is just comfortably above background.

Solution

Consider the following:

It may be possible to increase the signal by increasing the amount of DNA during transfection, but there are obvious limits to this approach.

If high resolution is not critically important, 2 × 2 binning will increase the signal by roughly fourfold.

Camera noise can be reduced by using a lower readout speed for the camera. This might require selecting only a subregion of the image.

DISCUSSION

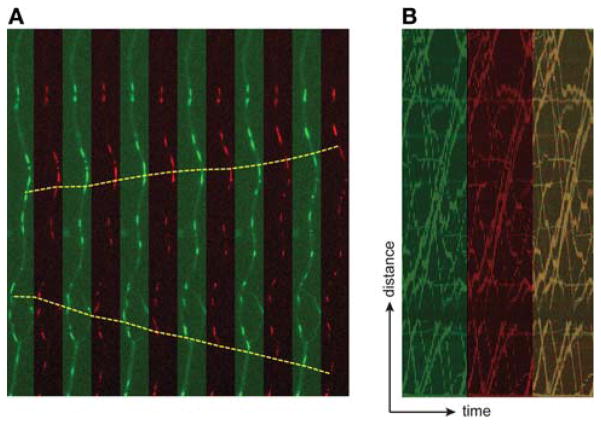

Figure 1 illustrates the axonal transport of vesicles labeled with GFP-tagged NgCAM, a cell adhesion molecule present on the axonal plasma membrane (see also Movie 1 at http://cshprotocols.cshlp.org). To identify vesicles en route to the cell surface, as opposed to those derived from endosomes, cells were cotransfected with a construct tagged with mCherry, which fills the lumen of carriers as they leave the Golgi complex but is released when vesicles fuse with the plasma membrane. Nearly all of the moving carriers were colabeled with both markers. These images were acquired using a spinning-disk confocal microscope to maximize the signal-to-noise ratio for these small, dim, rapidly moving organelles.

FIGURE 1.

Dual-color imaging of the vesicles that deliver membrane proteins from the Golgi complex to the axonal surface. This cell was cotransfected with the cell adhesion molecule NgCAM (tagged with GFP) and a construct that fills the interior of Golgi-derived vesicles (mCherry fused to the signal sequence of neuropeptide NPY). (A) Consecutive frames (7.2 sec from a 60-sec recording) show vesicles that undergo rapid transport in both anterograde and retrograde directions. Most vesicles were labeled with both constructs. The displacements of two representative vesicles are marked by the yellow lines. These images were acquired using a spinning-disk confocal microscope (Nikon TE2000 with Yokogawa CSU10 spinning-disk confocal) and a 60× 1.45-numerical aperture (NA). The microscope was equipped with a perfect focus system, an acousto-optical tunable filter–controlled multiline Kr:Ar ion laser (Coherent, Inc. Innova 70 Spectrum), and a Hamamatsu ORCA-ER camera. Images were acquired every 600 msec, switching sequentially between 488-nm and 568-nm laser excitation combined with emission filter switching (using a filter wheel). This neuron was cultured for 11 d and transfected with Lipofectamine 5 h before imaging. (B) Kymograph analysis of the 1-min recording shows that most carriers are labeled with both NgCAM (green) and mCherry (red).

This example also serves to emphasize the importance of matching the frequency of image acquisition with the expected dynamics of movement. Motor-mediated microtubule-based transport conveys vesicles along the axon at speeds as high as several micrometers per second. This translates to movements on the order of 20–30 pixels/sec when imaging with a 60× objective, although the vesicles themselves are often only a few pixels in diameter. When many similar organelles are present, imaging too slowly makes it impossible to track the movements of individual organelles. In this experiment, images were captured every half second, fast enough to follow vesicle movement. Sometimes vesicles appear round when stationary but take on an elongated appearance when they begin to move, a result of the movement that occurs during the exposure. Some reports in the literature use acquisition rates as slow as one frame every 510 sec to image axonal transport. This roughly corresponds to the interval between the first and the last frames in the sequence shown in Figure 1. When imaging axonal transport at such slow rates, only the slowest movements can be followed, which results in artifactually slow estimates of transport velocity.

RELATED INFORMATION

Certain developmental changes, such as those involving cell morphology and protein localization, occur over a time course of hours. In such cases, time-lapse studies are required that permit cells to be imaged repeatedly over prolonged periods without compromising cell survival. A protocol is available for Long-Term Time-Lapse Imaging of Developing Hippocampal Neurons in Culture (Kaech et al. 2012b).

Acknowledgments

Research in our laboratory is supported by National Institutes of Health Grants MH66179 and NS17112. The Advanced Light Microscopy Core is supported in part by P30 Center Grant NS061800.

References

- Kaech S, Banker G. Culturing hippocampal neurons. Nat Protoc. 2006;1:2406–2415. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2006.356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaech S, Huang C-F, Banker G. General considerations for live imaging of developing hippocampal neurons in culture. Cold Spring Harb Protoc. 2012a doi: 10.1101/pdb.ip068221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaech S, Huang C-F, Banker G. Long-term time-lapse imaging of developing hippocampal neurons in culture. Cold Spring Harb Protoc. 2012b doi: 10.1101/pdb.prot068239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]