Abstract

Dental caries is closely associated with the microbial disequilibrium between acidogenic/aciduric pathogens and alkali-generating commensal residents within the dental plaque. Fluoride is a widely used anticaries agent, which promotes tooth hard-tissue remineralization and suppresses bacterial activities. Recent clinical trials have shown that oral hygiene products containing both fluoride and arginine possess a greater anticaries effect compared with those containing fluoride alone, indicating synergy between fluoride and arginine in caries management. Here, we hypothesize that arginine may augment the ecological benefit of fluoride by enriching alkali-generating bacteria in the plaque biofilm and thus synergizes with fluoride in controlling dental caries. Specifically, we assessed the combinatory effects of NaF/arginine on planktonic and biofilm cultures of Streptococcus mutans, Streptococcus sanguinis, and Porphyromonas gingivalis with checkerboard microdilution assays. The optimal NaF/arginine combinations were selected, and their combinatory effects on microbial composition were further examined in single-, dual-, and 3-species biofilm using bacterial species–specific fluorescence in situ hybridization and quantitative polymerase chain reaction. We found that arginine synergized with fluoride in suppressing acidogenic S. mutans in both planktonic and biofilm cultures. In addition, the NaF/arginine combination synergistically reduced S. mutans but enriched S. sanguinis within the multispecies biofilms. More importantly, the optimal combination of NaF/arginine maintained a “streptococcal pressure” against the potential growth of oral anaerobe P. gingivalis within the alkalized biofilm. Taken together, we conclude that the combinatory application of fluoride and arginine has a potential synergistic effect in maintaining a healthy oral microbial equilibrium and thus represents a promising ecological approach to caries management.

Keywords: Streptococcus mutans, Streptococcus sanguis, Porphyromonas gingivalis, biofilms, dental caries, drug synergism

Introduction

Dental caries is closely associated with microbial metabolism of carbohydrates, which leads to acid accumulation and subsequent pH declination and selectively enriches acidogenic/aciduric species (e.g., mutans streptococci and lactobacilli) within biofilm and suppresses those less aciduric commensal residents (e.g., Streptococcus sanguinis). This feed-forward imbalance in microbial equilibrium leads to continuous pH decline to the critical pH, below which tooth hard-tissue demineralization begins and dental caries gradually occurs (Marsh 1994, 2003; Takahashi and Nyvad 2011).

Fluoride is a widely recognized dual functional anticaries agent (Hardwick et al. 2000; National Institutes of Health 2001), acting on both tooth hard tissue and oral microbes (Koo 2008; Featherstone 2009; ten Cate 2009). Fluoride acts as a glycolytic enzyme inhibitor as well as transmembrane proton carrier and thus inhibits bacteria by inducing cytoplasmic acidification (Van Loveren 2001). Arginine, as an alkali-generating substrate of the microbial arginine deiminase system (ADS; Burne and Marquis 2000), can further counter the acid accumulation within the oral biofilm and thus serves as a promising approach to caries management (Burne et al. 2012; Liu et al. 2012). Accumulating in vivo data have shown that arginine-containing oral hygiene products significantly reduced the incidence of dental caries (Acevedo et al. 2005, 2008). Toothpaste containing 1.5% arginine and 1450 ppm fluoride in a calcium base has also been proven more effective in arresting and reversing early carious lesions compared with dentifrice containing 1450 ppm fluoride alone (Kraivaphan et al. 2013; Srisilapanan et al. 2013; Yin et al. 2013). Since most of arginine-containing oral hygiene products also contain fluoride, the combinatory efforts of these 2 compounds on oral bacteria are worth further investigation.

Here, we hypothesize that arginine may augment the ecological benefit of fluoride by enriching alkali-generating bacteria in the biofilm and thus synergizes with fluoride in controlling dental caries. Specifically, we found that NaF/arginine synergistically suppressed Streptococcus mutans and enriched S. sanguinis within multispecies biofilm. Meanwhile, the optimal combination of NaF/arginine maintained a “streptococcal pressure” so as to prevent the potential overgrowth of anaerobic Porphyromonas gingivalis within the alkalized plaque biofilm.

Materials and Methods

Bacterial Strains and Growth Media

S. mutans UA159, S. sanguinis ATCC10556, and P. gingivalis ATCC33277 were commercially obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC). S. mutans and S. sanguinis were routinely grown at 37 °C under aerobic condition (5% CO2) in brain heart infusion broth (BHI; Difco, Sparks, MD), and P. gingivalis was grown at 37 °C under anaerobic condition (90% N2, 5% CO2, 5% H2) in BHI containing 1 µg/mL hemin (Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA) and 1 µg/mL menadione (Sigma; designated BHIHK). Inoculum for the experiment was adjusted to 1 × 107 CFU/mL for S. mutans and S. sanguinis and 2 × 107 CFU/mL for P. gingivalis based on the OD600 nm versus CFU/mL graph of each bacterium and further 1:10 diluted in the growth culture. When needed, medium was supplemented with 1% sucrose (designated BHIS or BHIHKS), NaF, or arginine (L-arginine monohydrochloride; Sigma, catalog No. A5131), and the pH value was adjusted to 7.0 before experiment.

Checkerboard Microdilution Assay

The potential synergistic/antagonistic effects of the NaF/arginine combination on the growth of each bacterium in either planktonic or biofilm cultures were determined by checkerboard microdilution assays as described previously (Wei et al. 2011). Each well of the 96-well microtiter plate contained bacteria (1 × 106 CFU/mL), BHI, and serially diluted test agents in combination. The final concentrations of NaF ranged from 15.625 to 250 ppm, and arginine concentrations ranged from 0.625% to 10%. After 24 h, cell growth was examined by OD600 nm. The fractional inhibitory concentration (FIC) was defined as the ratio of the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) of an agent used in combination to the MIC of the agent used alone. The FIC index (ΣFIC, the sum of individual FICs) indicates synergy (<0.5), indifference (0.5 to 4.0), or antagonism (>4.0). The synergism and antagonism against biofilm were evaluated similarly, except that the minimum biofilm inhibitory concentration, instead of the MIC, of each agent was determined by the method described previously (Xu et al. 2011; see the Appendix for details).

Bacteria/Extracellular Polysaccharides Staining

Overnight cultures of S. mutans or S. sanguinis were inoculated on a saliva-coated glass coverslip in a 24-well cell culture plate. The BHIS and test agent alone or in different combinations were added into the culture well and incubated aerobically (5% CO2) at 37 °C for 24 h. The pH values of the spent media were measured with an Orion Dual Star pH/ISE electrode (Thermo Scientific, Schwerte, Germany). The bacteria and extracellular polysaccharides (EPS) of biofilms were double-labeled with fluorescence as previously described by Xiao et al. (2012). Biofilm images were captured using a Leica DMIRE2 confocal laser scanning microscope (Leica, Wetzlar, Germany). The biofilm and EPS amounts were calculated based on the integral optical density (IOD) with Image pro plus 6.0 (Media Cybernetics, Silver Spring, MD, USA; see the Appendix for details).

Bacterial Composition Analysis in Dual- and 3-Species Biofilm

Overnight cultures of S. mutans and S. sanguinis were simultaneously inoculated (inoculum ratio = 1:1) on saliva-coated glass coverslips in a 24-well plate. BHIS and test agent alone or in different combinations were added into the culture well and incubated aerobically at 37 °C (5% CO2) for 24 h. The pH values of the spent media were measured with an Orion Dual Star pH/ISE electrode (Thermo Scientific). The 24-h dual-species biofilms were then fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde and labeled by species-specific fluorescent in situ hybridization (FISH) probes, as previously described (Zheng et al. 2013). Confocal image series were generated by optical sectioning at 5 randomly selected positions. Three-dimensional reconstruction was performed by Imaris 7.0.0 (Bitplane, Zürich, Switzerland; see the Appendix for details). The bacterial composition was further quantified by species-specific real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) by the method described by Yoshida et al. (2003; see the Appendix for details).

To evaluate the effect of NaF/arginine alone or in combination on the 3-species biofilm, a 48-h culture of P. gingivalis was inoculated into the BHIHKS medium containing S. mutans/S. sanguinis (inoculum ratio of S. mutans/S. sanguinis/P. gingivalis = 1:1:2) and test agent alone or in different combinations. The 24-well plate was incubated anaerobically for either 24 h or 48 h. The pH values of the spent media were measured with an Orion Dual Star pH/ISE electrode (Thermo Scientific). The 3-species biofilms were labeled by species-specific FISH probes, and biofilm images were examined using an Olympus BX3-CBH fluorescence microscope (Olympus Corp., Tokyo, Japan). Images were processed using Cell Sens Dimension (Olympus Corp.), and bacterial composition was calculated based on IOD with Image pro plus 6.0 (Media Cybernetics; see the Appendix for details).

Statistical Analysis

All experiments were performed in triplicate and reproduced at least 3 separate times. Statistical analysis of data was performed with SPSS (version 16.0 for Windows; SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) using 1-way analysis of variance to compare the means of all groups and followed by Student-Newman-Keuls test to compare the means of each of the 2 groups. Data were considered significantly different if the 2-tailed P value was <0.05.

Results

NaF/Arginine Combination Synergistically Suppresses S. mutans in Both Planktonic and Biofilm Cultures

The fraction of inhibitory concentration (ΣFIC) of the NaF/arginine combination against S. mutans was 0.458 (Fig. 1A), indicating a synergistic effect of these 2 agents against S. mutans planktonic culture. Moreover, the NaF/arginine combination exhibited a more significant synergistic effect against S. mutans biofilm with a ΣFIC of 0.313 (Fig. 1B). However, the NaF/arginine combination exhibited no synergistic effects against planktonic and biofilm cultures of either S. sanguinis (ΣFIC = 0.917 for planktonic culture and ΣFIC = 0.750 for biofilm) or P. gingivalis (ΣFIC = 0.833 for planktonic culture and ΣFIC = 1.167 for biofilm) compared with each agent used alone (Fig. 1C, D; and Appendix Table 1).

Figure 1.

The antimicrobial effects of NaF and arginine alone or in combination against the planktonic and biofilm cultures of S. mutans/S. sanguinis. (A, B) Checkerboard microdilution assays on S. mutans planktonic (A) and biofilm cultures (B), respectively. (C, D) Checkerboard microdilution assays on S. sanguinis planktonic (C) and biofilm cultures (D), respectively. The data (normalized by the mean of nonagent control) are reported as the mean of at least 3 separate tests. Black arrows indicate the minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs) or minimum biofilm inhibitory concentrations (MBICs) of NaF and arginine alone, and the blue arrows indicate the MICs or MBICs in combination. The red dashed box indicates the NaF/arginine combinations that showed no significant inhibitory effect on the growth of S. sanguinis.

We further chose 2 NaF/Arg combinations with different fractions of each agent to perform the following experiments based on data obtained from the checkerboard microdilution assays. One combination contained relatively higher concentrations of NaF/Arg (HC combination; 125 ppm NaF and 2.5% Arg), and another contained lower concentrations of each agent (LC combination; 31.25 ppm NaF and 0.625% Arg). Both HC and LC combinations significantly disrupted the microarchitecture of the S. mutans biofilm compared with each agent used alone (Fig. 2A, B). Conversely, although the HC combination disrupted the S. sanguinis biofilm, the LC combination showed no significant antimicrobial effect against the S. sanguinis biofilm when compared with each agent used alone (Fig. 2C, D). Notably, both NaF/arginine combinations and the arginine treatment alone almost completely abolished the EPS production of S. mutans biofilm compared with NaF used alone (Fig. 2A, B). Similar significant inhibitory effects, although to a lesser extent, against S. sanguinis EPS production were observed in either NaF/arginine combinations or arginine treatment alone compared with NaF treatment alone (Fig. 2C, D).

Figure 2.

Effects of NaF/arginine combinations on the S. mutans and S. sanguinis single-species biofilms. (A, B) Representative images of S. mutans biofilms treated with either high concentration (HC, A) or low concentration (LC, B) of NaF/arginine combinations. (C, D) Representative images of S. sanguinis biofilms treated with either HC (C) or LC (D) of NaF/arginine combinations. Green, bacteria (SYTO 9); red, extracellular polysaccharides (EPS; Alexa Fluor 647 [Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY, USA]). Confocal images were taken at 63× magnification. (E, F) The quantitative data of bacterial/EPS amount and pH values of spent media of either S. mutans (E) or S. sanguinis (F). Results were averaged from 3 separate experiments and are presented as mean ± standard deviation. Different lowercase letters indicate a significant intergroup difference of bacterial (green letters)/EPS (red letters) amount or pH values (black letters).

Fluoride treatment significantly inhibited the acid production of both S. mutans and S. sanguinis as demonstrated by an increase of pH value in the spent media of both bacteria (Fig. 2E, F). The addition of arginine to the fluoride treatment failed to further increase the pH values in the spent media of S. mutans culture, possibly because of the reported absence of arginine deminase in this bacterium (Liu et al. 2012). Conversely, the fluoride/arginine combination treatment significantly increased the pH values of S. sanguinis culture compared with the treatment with each agent alone (Fig. 2F), indicating a base generation by the microbial metabolism of arginine.

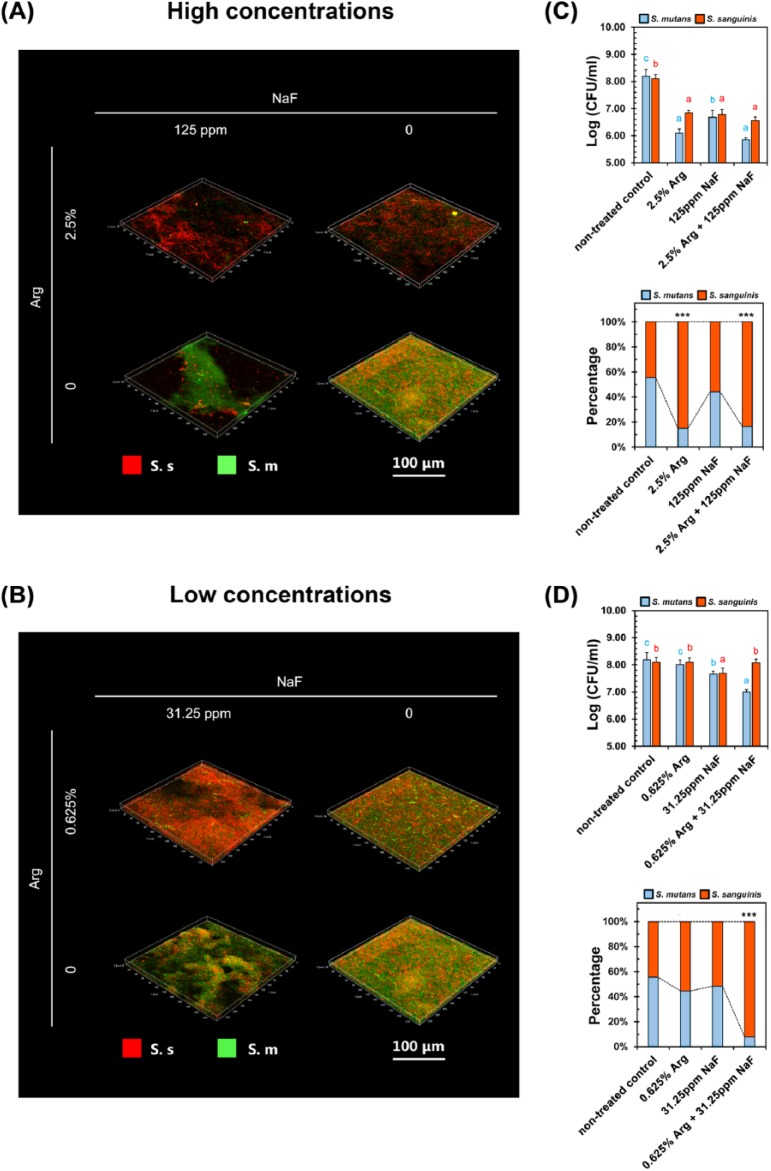

NaF/Arginine Combination Enriches S. sanguinis within Dual-Species Biofilms

The combinatory effects of NaF/arginine against oral streptococci were further investigated in the context of dual-species biofilm with species-specific FISH and qPCR. The confocal microscopic images of FISH-labeled biofilms and qPCR quantitative data showed that both HC and LC combinations reversed the S. mutans/S. sanguinis ratio toward an S. sanguinis-predominant consortium (Fig. 3A–D). Notably, HC and LC combinations exhibited distinct modes of action. The HC combination suppressed the absolute number of both S. mutans and S. sanguinis but promoted the numerical dominance of S. sanguinis in the dual-species biofilm compared with the nontreated control (Fig. 3A, C). Conversely, the LC combination selectively suppressed S. mutans while keeping the growth of S. sanguinis intact compared with either the nontreated control or treatment with each agent alone (Fig. 3B, D). Thus, the net result of the LC combination treatment was target inhibition of S. mutans and enrichment of S. sanguinis in abundance (Fig. 3B, D). In addition, 2.5% arginine treatment alone exhibited a similar action pattern on the dual-species biofilm compared with the HC combination (Fig. 3A, C), but NaF treatment nonselectively suppressed both S. mutans and S. sanguinis without significantly up-regulating the relative abundance of S. sanguinis within the dual-species biofilm (Fig. 3A–D). Furthermore, addition of arginine to the fluoride treatment further neutralized the biofilm acidification, as reflected by an increase of pH values in the dual biofilm culture grown under the sucrose-rich condition (Fig. 4A).

Figure 3.

Effects of NaF/arginine combinations on the S. mutans/S. sanguinis dual-species biofilms. (A, B) Representative confocal microscopic images of S. mutans/S. sanguinis dual-species biofilms treated with high concentration (HC, A) or low concentration (LC, B) of NaF/arginine combinations or each agent alone. S. mutans (S. m, green) and S. sanguinis (S. s, red) were labeled with species-specific fluorescent in situ hybridization probes. Image stacks were captured by confocal laser scanning microscope at 63× magnification and reconstructed using Imaris 7.0.0. (C, D) Quantitative data of bacterial composition of S. mutans/S. sanguinis dual-species biofilms treated with either HC (C) or LC (D) of NaF/arginine combinations. The microbial composition was quantified by species-specific quantitative polymerase chain reaction. Results were averaged from 3 separate experiments and are presented as mean ± standard deviation. Different lowercase letters indicate significant intergroup difference of S. mutans (blue letters) or S. sanguinis (red letters), respectively. ***Significant difference compared with nontreated controls (P < 0.001).

Figure 4.

pH values of spent media of the dual-species (A) or 3-species (B) biofilms treated with either high concentrations (HC) or low concentrations (LC) of NaF/arginine combinations. Results were averaged from 3 separate experiments and are presented as mean ± standard deviation. Different lowercase letters indicate significant intergroup differences of pH values.

NaF/Arginine Combination Maintains a “Streptococcus Pressure” to Suppress the Overgrowth of P. gingivalis in the Alkalized Biofilm

To examine whether potential alkalization of biofilm will result in overgrowth of oral anaerobes, we further analyzed the combinatory effects of NaF/arginine on the microbial composition of an in vitro 3-species biofilm, which consisted of S. mutans, S. sanguinis, and P. gingivalis. Treatment with fluoride/arginine combinations increased the pH values of the 3-species biofilm culture in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 4B). Quantitative analysis of FISH-labeled 24-h 3-species biofilms showed that streptococci, particularly S. mutans, were numerically predominant in the 3-species biofilm (Fig. 5A; Appendix Fig. 1). Treatment with 500 ppm NaF alone significantly suppressed both S. mutans and S. sanguinis and led to the overgrowth of P. gingivalis within the biofilm compared with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS)–treated control (Appendix Fig. 1). The HC combination treatment for 24 h showed a similar trend in suppressing both S. mutans and S. sanguinis, but it resulted in the overgrowth of P. gingivalis compared with the PBS-treated control (Fig. 5A, B). Although regrowth of S. sanguinis was observed in the 48-h treated biofilm, the percentage of total streptococci (S. mutans + S. sanguinis) in the HC combination–treated biofilm was still significantly lower than the biofilm treated with PBS, and P. gingivalis still predominated in the biofilm (Fig. 5A, B, D). Conversely, the LC combination treatment enriched S. sanguinis (about 80% in abundance) and significantly suppressed S. mutans (about 17% in abundance) compared with PBS-treated control (Fig. 5A, C, D). More importantly, the LC combination treatment maintained the streptococcus dominance and thus suppressed the abundance of P. gingivalis to a low level comparable with the PBS-treated control (Fig. 5A–D).

Figure 5.

Effects NaF/arginine combinations on the S. mutans/S. sanguinis/P. gingivalis 3-species biofilms. (A–C) Representative images of 3-species biofilms treated with phosphate-buffered saline (A), high concentration (HC, B) or low concentration (LC, C) of NaF/arginine combinations. S. sanguinis (S. s, red), S. mutans (S. m, green), and P. gingivalis (P. g, blue) were labeled with species-specific fluorescent in situ hybridization (FISH) probes. Images were captured by fluorescence microscope at 60× magnification. (D) Quantitative data of bacterial composition based on the integral optical density of FISH-labeled biofilms. Results were averaged from 3 separate experiments and are presented as mean ± standard deviation. Different lowercase letters indicate significant intergroup differences of S. mutans (green letters), S. sanguinis (red letters), or P. gingivalis (blue letters), respectively.

Discussion

Dental caries is a result of microbial disequilibrium characterized by the enrichment of acidogenic pathogens and depletion of alkali-generating commensal residents within the plaque biofilm (Marsh 1994; Kleinberg 2002; Marsh 2003; Takahashi and Nyvad 2011). Therefore, maintaining or restoring the microbial equilibrium within the plaque biofilms is critical for the treatment or prevention of dental caries (Marsh 1994, 2003). To evaluate the combinatory effects of fluoride and arginine on oral microbiota in vitro, we employed a dual-species biofilm model to demonstrate the mode of action of these 2 compounds on the equilibrium of a selected acidogenic pathogen (S. mutans) and alkali-generating commensal resident (S. sanguinis). We further added a representative oral anaerobe (P. gingivalis) to the S. mutans/S. sanguinis consortium to explore the ecological consequence of potential overalkalization of oral biofilm. It should be noted that oral microbiota is a dynamic consortium of hundreds of microbial species distinctly colonized at different oral niches (Xu et al. 2014), and data obtained from the selected microbial consortium in the current study indicate only a trend of microbial modulating effects of fluoride/arginine.

In the current study, we first quantitatively analyzed the dual and 3-species biofilm after fluoride treatment with species-specific FISH and qPCR. We found that fluoride not only inhibited acidogenic S. mutans but also suppressed commensal S. sanguinis within the biofilm. This result further supports our efforts to investigate compound that is able to augment the ecological benefit of fluoride. Since arginine can be metabolized by the microbial ADS to produce alkaline (Burne and Marquis 2000), it may favor the growth of commensal bacteria and impair the competitiveness of acidogenic/aciduric bacteria by neutralizing excessive acid within the plaque biofilm. Here we found that the combinatory application of NaF/arginine selectively suppressed S. mutans and promoted the numerical dominance of S. sanguinis in both dual and 3-species biofilm. Although the exact mechanisms of this microbial selection are still unclear, we speculate that fluoride suppresses acid production while arginine contributes to an additional pH rise, thus impairing the selection of acid-tolerant S. mutans within the less acidic biofilm. The rebound of alkali-generating commensal residents (S. sanguinis) within the multispecies biofilm is indicative of an ecological benefit of the NaF/arginine combination in terms of caries management. Indeed, piecemeal data obtained from clinical trials have shown the greater long-term effect of arginine-containing fluoride dentifrice over conventional fluoride dentifrice (Kraivaphan et al. 2013; Srisilapanan et al. 2013; Yin et al. 2013). Our findings that NaF/arginine exhibited greater ecology-promoting effects on oral microbial consortium may possibly contribute to the rationale of clinical application of fluoride/arginine combination in caries prevention.

One of the major concerns of the application of alkali-generating products in caries management is that plaque alkalization may promote the overgrowth of oral anaerobes such as P. gingivalis (Socransky and Haffajee 2005; Takahashi 2003; Zilm et al. 2010) and thus be detrimental to periodontal health. Our data obtained from the in vitro 3-species biofilm have shown that if applied at proper concentration (i.e., LC combination in this study), the fluoride/arginine combination prevented excessive alkalization of the biofilm and thus not only reversed the S. mutans/S. sanguinis equilibrium toward a more ecological ratio in favor of caries prevention but also maintained the predominance of these 2 oral streptococci over P. gingivalis within the biofilm. Although the exact mechanisms of this observation are not clear, we believe that the NaF/arginine combination possibly acts by taking advantage of the interspecies antagonism between oral streptococci and oral anaerobes. While NaF nonselectively suppresses both S. mutans and S. sanguinis, arginine may relieve the growth pressure of S. sanguinis through the ADS-mediated alkali-production (Burne et al. 2012; Liu et al. 2012). The coexistence of fluoride/arginine eases the competitive edge of S. mutans over S. sanguinis, and the subsequent overgrowth of S. sanguinis compensates the total streptococcal load by replacing S. mutans. Hence, the NaF/arginine combination at a proper concentration is able to maintain a sustained streptococcal pressure against P. gingivalis within the biofilm, possibly through the microbial production of acidic (e.g., lactic acid) and oxidative metabolites (e.g., H2O2; Hillman and Socransky 1989). However, further studies on more comprehensive models are needed to validate this hypothesis.

Interestingly, we also observed that the NaF/arginine combination almost completely abolished EPS production by either S. mutans or S. sanguinis biofilm. This phenotypic observation is likely due to substrate competition between arginine and carbohydrate, as well as the suppressive effect of fluoride as a glycolytic enzyme inhibitor (Koo 2008; Van Loveren 2001). Since bacteria-derived EPS has been recognized as a critical virulence determinant in cariogenic biofilms (Koo et al. 2013; Xiao et al. 2012), the significant anti-EPS effect of the fluoride/arginine combination further suggests its beneficiary potential in the ecological management of dental caries.

Some cautions should be taken when interpreting data from this study. Batch culture with constant treatment instead of flow culture with pulse treatment was used to evaluate the synergistic effect of fluoride/arginine against selected oral bacterial consortia. The data only indicate the potential synergistic effects of the fluoride/arginine combination on selected microbial consortia, whereas its exact efficacy should be further determined in vivo with optimal delivery method (either as rinse/dentifrice or varnish). In addition, culture-independent methods (e.g., qPCR or FISH) were used to evaluate the ecological benefit of the fluoride/arginine combination. These techniques quantify or label both live and dead bacteria, thus reflecting the microbial composition instead of viable bacterial count within the multispecies biofilms. Therefore, data obtained from this study could better be interpreted as potential ecological benefit rather than antimicrobial efficacy.

In conclusion, our in vitro data demonstrate that arginine may augment the ecological benefit of fluoride by enriching alkali-generating S. sanguinis in the multispecies biofilm. A proper combination of fluoride/arginine could also prevent the overgrowth of periodontal pathogen P. gingivalis and thus represents a promising ecological approach to caries management.

Author Contributions

X. Zheng, contributed to conception, design, data acquisition, analysis, and interpretation, drafted and critically revised the manuscript; X. Cheng, L. Wang, W. Qiu, contributed to design, data acquisition, analysis, and interpretation, drafted the manuscript; S. Wang, Y. Zhou, contributed to design and data interpretation, drafted the manuscript; M. Li, Y. Li, L. Cheng, J. Li, contributed to conception, design, and data interpretation, drafted the manuscript; X. Zhou, X. Xu, contributed to conception, design, and data interpretation, drafted and critically revised the manuscript. All authors gave final approval and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Footnotes

This work was supported by the National Science & Technology Pillar Program during the 12th Five-Year Plan Period (grant 2012BAI07B03), National Natural Science Foundation of China (grants 81200782, 81170959), and Doctoral Fund of Ministry of Education of China (grant 20120181120002).

The authors declare no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the authorship and/or publication of this article.

A supplemental appendix to this article is published electronically only at http://jdr.sagepub.com/supplemental.

References

- Acevedo AM, Machado C, Rivera LE, Wolff M, Kleinberg I. 2005. The inhibitory effect of an arginine bicarbonate/calcium carbonate CaviStat-containing dentifrice on the development of dental caries in Venezuelan school children. J Clin Dent. 16(3):63–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Acevedo AM, Montero M, Rojas-Sanchez F, Machado C, Rivera LE, Wolff M, Kleinberg I. 2008. Clinical evaluation of the ability of CaviStat in a mint confection to inhibit the development of dental caries in children. J Clin Dent. 19(1):1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burne RA, Marquis RE. 2000. Alkali production by oral bacteria and protection against dental caries. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 193(1):1–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burne RA, Zeng L, Ahn SJ, Palmer SR, Liu Y, Lefebure T, Stanhope MJ, Nascimento MM. 2012. Progress dissecting the oral microbiome in caries and health. Adv Dent Res. 24(2):77–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Featherstone JD. 2009. Remineralization, the natural caries repair process—the need for new approaches. Adv Dent Res. 21(1):4–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardwick K, Barmes D, Richardson LM. 2000. International collaborative research on fluoride. J Dent Res. 79(4):893–904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hillman JD, Socransky SS. 1989. The theory and application of bacterial interference to oral diseases. In: Myers HM, editor. New biotechnology in oral research. Basel (Switzerland): Karger; P. 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Kleinberg I. 2002. A mixed-bacteria ecological approach to understanding the role of the oral bacteria in dental caries causation: an alternative to Streptococcus mutans and the specific-plaque hypothesis. Crit Rev Oral Biol Med. 13(2):108–125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koo H. 2008. Strategies to enhance the biological effects of fluoride on dental biofilms. Adv Dent Res. 20(1):17–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koo H, Falsetta ML, Klein MI. 2013. The exopolysaccharide matrix: a virulence determinant of cariogenic biofilm. J Dent Res. 92(12):1065–1073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraivaphan P, Amornchat C, Triratana T, Mateo LR, Ellwood R, Cummins D, DeVizio W, Zhang YP. 2013. Two-year caries clinical study of the efficacy of novel dentifrices containing 1.5% arginine, an insoluble calcium compound and 1,450 ppm fluoride. Caries Res. 47(6):582–590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu YL, Nascimento M, Burne RA. 2012. Progress toward understanding the contribution of alkali generation in dental biofilms to inhibition of dental caries. Int J Oral Sci. 4(3):135–140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsh PD. 1994. Microbial ecology of dental plaque and its significance in health and disease. Adv Dent Res. 8(2):263–271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsh PD. 2003. Are dental diseases examples of ecological catastrophes? Microbiology. 149(2):279–294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Institutes of Health. 2001. Diagnosis and management of dental caries throughout life. NIH Consensus Statement. 18(1):1–30 [accessed 2014 Nov 4]. http://consensus.nih.gov/2001/2001DentalCaries115PDF.pdf. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Socransky SS, Haffajee AD. 2005. Periodontal microbial ecology. Periodontol 2000. 38(1):135–187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srisilapanan P, Korwanich N, Yin W, Chuensuwonkul C, Mateo LR, Zhang YP, Cummins D, Ellwood RP. 2013. Comparison of the efficacy of a dentifrice containing 1.5% arginine and 1450ppm fluoride to a dentifrice containing 1450ppm fluoride alone in the management of early coronal caries as assessed using quantitative light-induced fluorescence. J Dent. 41(2 Suppl):S29–S34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi N. 2003. Acid-neutralizing activity during amino acid fermentation by Porphyromonas gingivalis, Prevotella intermedia and Fusobacterium nucleatum . Oral Microbiol Immunol. 18(2):109–113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi N, Nyvad B. 2011. The role of bacteria in the caries process ecological perspectives. J Dent Res. 90(3):294–303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ten Cate JM. 2009. The need for antibacterial approaches to improve caries control. Adv Dent Res. 21(1):8–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Loveren C. 2001. Antimicrobial activity of fluoride and its in vivo importance: identification of research questions. Caries Res. 35(1 Suppl):65–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei GX, Xu X, Wu CD. 2011. In vitro synergism between berberine and miconazole against planktonic and biofilm Candida cultures. Arch Oral Biol. 56(6):565–572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao J, Klein MI, Falsetta ML, Lu B, Delahunty CM, Yates JR, III, Heydorn A, Koo H. 2012. The exopolysaccharide matrix modulates the interaction between 3D architecture and virulence of a mixed-species oral biofilm. PLoS Pathog. 8(4):e1002623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu X, He J, Xue J, Wang Y, Li K, Zhang K, Guo Q, Liu X, Zhou Y, Cheng L, et al. Forthcoming 2014. Oral cavity contains distinct niches with dynamic microbial communities. Environ Microbiol. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu X, Zhou XD, Wu CD. 2011. The tea catechin epigallocatechin gallate suppresses cariogenic virulence factors of Streptococcus mutans . Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 55(3):1229–1236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin W, Hu DY, Li X, Fan X, Zhang YP, Pretty IA, Mateo LR, Cummins D, Ellwood RP. 2013. The anti-caries efficacy of a dentifrice containing 1.5% arginine and 1450ppm fluoride as sodium monofluorophosphate assessed using quantitative light-induced fluorescence (QLF). J Dent. 41(2 Suppl):S22–S28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida A, Suzuki N, Nakano Y, Kawada M, Oho T, Koga T. 2003. Development of a 5′ nuclease-based real-time PCR assay for quantitative detection of cariogenic dental pathogens Streptococcus mutans and Streptococcus sobrinus . J Clin Microbiol. 41(9):4438–4441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng X, Zhang K, Zhou X, Liu C, Li M, Li Y, Wang R, Li Y, Li J, Shi W, et al. 2013. Involvement of gshAB in the interspecies competition within oral biofilm. J Dent Res. 92(9):819–824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zilm PS, Mira A, Bagley CJ, Rogers AH. 2010. Effect of alkaline growth pH on the expression of cell envelope proteins in Fusobacterium nucleatum . Microbiology. 156(Pt 6):1783–1794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]