Abstract

The authors examined whether perception of contralateral limb strength is altered and whether perception of strength correlates with perception of stimulus intensity (magnitude) in a prospective sample of patients with unilateral right (RHL: n = 13) and left (LHL: n = 6) hemisphere lesions due to stroke. Patients with RHL tended to overestimate strength and patients with LHL tended to underestimate strength; both patterns were highly correlated with altered perception of stimulus magnitude.

It is unknown whether most patients perceive motor function accurately after stroke. Perception of strength is overestimated by patients with right hemisphere lesions (RHLs) who either deny or lack concern about hemiplegia (anosognosia and anosodiaphoria, respectively).1 Catastrophic emotional reactions following stroke, more commonly associated with left hemisphere lesions (LHLs),2 imply an overreaction to deficit; however, perception of motor function has not been examined in these patients or in prospective samples of stroke patients unselected for deficits in awareness.

It is also unknown whether perception of strength and sensory stimulation are related. Both sensory thresholds and perception of suprathreshold stimulus intensity (magnitude estimation) are commonly altered after stroke.3,4 Magnitude estimation is mediated by a distributed cortical system in each cerebral hemisphere with critical components suggested by fMRI studies in temporoparieto-occipital cortex.5,6 Estimates of strength and stimulus intensity may be mediated by the same system, in which case, altered perception of strength and stimulus intensity should be correlated in persons with disruption of the system due to stroke.

This pilot study investigated two questions: 1) Is perception of strength altered in prospective samples of patients with RHLs and LHLs who are unselected for deficits in awareness? 2) Is perception of contralateral strength correlated with perception of stimulus magnitude (line length)? We used line length estimation because it is sensitive to change in magnitude estimation following unilateral brain injury3,4 and because it is not confounded by elevated sensory thresholds contralateral to brain injury.

Methods

The study was approved by the University’s Institutional Review Board. Thirteen patients with unilateral RHLs (mean age = 55.2 years, SD = 15.8) and six patients with LHLs (mean = 47.0, SD = 22.2) due to stroke were tested as part of a standard clinical evaluation upon admission to a subacute rehabilitation hospital (mean stroke chronicity was 15.4 days, SD = 14.5 for RHLs and 12.7, SD = 8.6 for LHLs). Fewer patients with LHLs than patients with RHLs were included because aphasia precludes assessment of magnitude estimation. Lesion information was obtained from the neuroradiologic reports of clinically obtained brain scans (table). Lesion involvement was coded by anatomic region using published templates.7 Unilateral neglect was assessed using line bisection8 and line cancellation tests.9 Awareness of functional limitation (AFL) was assessed using a four-question, 8-point scale (8 = full awareness). Conventional strength ratings using a 0 to 5 scale were made by a physiatrist (X.Z.). Patient ratings of strength were obtained for each upper and each lower extremity by a neuropsychologist (J.H.B.) using a 0 to 10 scale (10 = normal). A strength estimation accuracy (SEA) score was derived from both ratings as follows: SEA = [patient rating − (physiatrist rating) · 2]. Zero indicates agreement, a positive score suggests a patient’s overestimation of strength, and a negative score suggests underestimation relative to the physiatrist’s rating.

Table.

Patient/lesion information and independent variables

| Code | Age | AFL | SEA | Exp | ST | TSS | Neuroanatomic regions |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LHL1 | 79 | 7 | 2.0 | 0.90 | I | 14 | Supra- and paraventricular |

| LHL2 | 65 | 8 | 0 | 0.92 | I | 6 | Superior temporal gyrus, putamen, lateral thalamus, supraventricular |

| LHL3 | 19 | 8 | 0 | 1.01 | I | 4 | Posterior putamen and internal capsule |

| LHL4 | 30 | 8 | −1.5 | 1.03 | H | 19 | Posterior cingulate gyrus, superior parietal lobe |

| LHL5 | 49 | 8 | −2.0 | 1.03 | I | 7 | Thalamus, paraventricular |

| LHL6 | 40 | 8 | −1.0 | 1.04 | H | 26 | Posterior cingulate gyrus, posterior central gyrus, superior parietal lobe, paraventricular |

| RHL7 | 55 | 8 | 8.0 | 0.94 | I | 9 | Frontal operculum, superior temporal gyrus, putamen, interior posterior central gyrus |

| RHL8 | 53 | 2 | 3.0 | 0.94 | I | 9 | Putamen, insula, supraventricular |

| RHL9 | 51 | 6 | 1.5 | 0.94 | H | 27 | Mesial superior frontal lobe, dorsolateral prefrontal, Anterior cingulate |

| RHL10 | 32 | 4 | 2.0 | 0.95 | HC | 53 | Putamen, posterior internal capsule, lateral thalamus |

| RHL11 | 39 | 8 | 1.0 | 0.99 | I | 12 | Frontal operculum, superior temporal gyrus, putamen |

| RHL12 | 44 | 8 | 0 | 0.99 | I | 9 | Posterior temporal lobe, angular gyrus, superior lateral occipital |

| RHL13 | 76 | 8 | 2.0 | 1.01 | H | 6 | Posterior lateral thalamus |

| RHL14 | 84 | 6 | −3.5 | 1.01 | I | 5 | Frontal lobe, paraventricular |

| RHL15 | 62 | 6 | 0 | 1.01 | I | 7 | Superior temporal gyrus, insula |

| RHL16 | 63 | 7 | 0 | 1.03 | I | 12 | Frontal lobe, para- and supraventricular, inferior cingulate gyrus |

| RHL17 | 47 | 2 | 1.0 | 1.03 | I | 36 | Frontal operculum, precentral/posterior central gyrus, posterior temporal lobe, supramarginal gyrus |

| RHL18 | 73 | 5 | 0 | 1.12 | I | 8 | Frontal lobe, paraventricular |

| RHL19 | 38 | 5 | 0 | 1.19 | I | 7 | Anterior cingulate gyrus, precentral/posterior central gyrus, posterior temporal lobe, inferior parietal lobe, superior lateral occipital |

LHL = left hemisphere lesion; RHL = right hemisphere lesion; AFL = awareness of functional limitation; SEA = strength estimation accuracy; Exp = exponent; ST = stroke type; TSS = time since stroke in days; I = ischemic; H = hemorrhagic; HC = hemorrhagic conversion.

Magnitude estimates of line length were derived from line bisection based on previous studies3,4 that used five different line lengths (1.7, 3.2, 6.3, 12.5, and 25 cm.). Length estimation is calculated for patients with RHLs by doubling the distance from the right end of the line to the bisection mark and from the left end for patients with LHLs. This procedure yields results similar to having subjects reproduce line lengths either directly or from memory.4 Data were log-transformed to make them linear and estimates of length were regressed on measured length to yield power functions. The slope or exponent of the power function summarizes the relationship between subjective and objective measures of line length. The size of the exponent for length estimation in normal subjects is 1.10 Altered perception of line length following RHL has been associated with a decreased exponent.3,4

Analyses

Mean SEA scores were compared between groups using the Mann-Whitney U test. Correlations between the SEA scores and power function exponents (and between the SEA and AFL scores for RHL patients) were calculated using Spearman’s ρ

Results

The AFL scores for patients with LHLs (mean = 7.83, SE = 0.17) were higher than for patients with RHLs (mean = 5.77, SE = 0.59) (Mann-Whitney U = 14.5, p < 0.023). The AFL scores in patients with RHLs were variable but did not correlate with the SEA scores (p > 0.05). Only two patients with RHLs (Patients RHL7 and RHL19) demonstrated neglect on both bisection and cancellation tests. No patient denied contralateral weakness when present (anosognosia), and none exhibited a catastrophic reaction to stroke clinically.

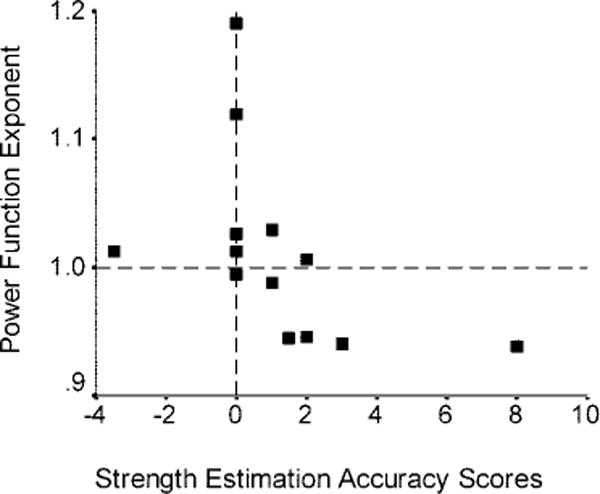

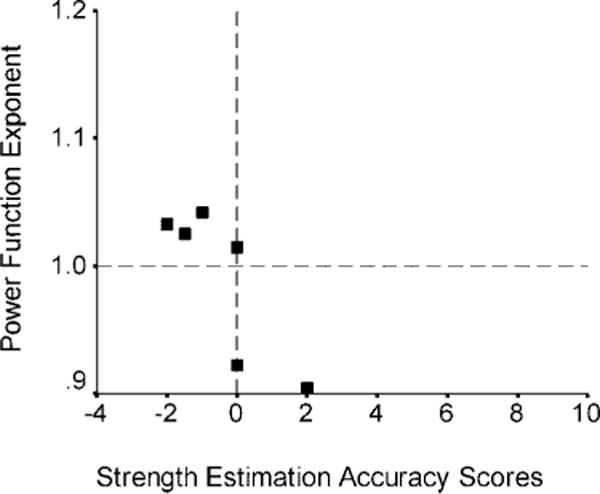

Group comparisons of the SEA scores revealed a trend (Mann-Whitney U = 19.5, p < 0.08) toward overestimation of strength in patients with RHLs (mean = 1.15, SE = 0.72) and underestimation in LHL patients (mean = −0.42, SE = 0.58). This trend was carried by a subset of patients as five patients with RHLs had ratings that agreed with the physician and one produced a negative SEA score and two patients with LHLs had ratings that agreed with the physician and one produced a positive SEA score. The mean power function exponent for length estimation was not different between patients with RHLs (mean = 1.01, SE = 0.02) and patients with LHLs (mean = 0.98, SE = 0.02); however, five patients with RHLs (38%) produced low exponents and three patients with LHLs (50%) produced high exponents. Contralateral SEA score correlated with the size of the exponent for both patients with RHLs (rs = −0.74, p = 0.01) and patients with LHLs (rs = −0.81, p = 0.05), but the pattern of association was opposite between groups. The SEA score increased as the power function exponent decreased among patients with RHLs (figure 1) and the SEA score decreased as the exponent increased among patients with LHLs (figure 2).

Figure 1.

Plot of the power function exponents for length estimation against strength estimation accuracy scores for contralateral strength. A subset of patients with right hemisphere lesions with low exponents overestimate contralateral strength.

Figure 2.

Plot of the power function exponents for length estimation against strength estimation accuracy scores for contralateral strength. A subset of patients with left hemisphere lesions with high exponents underestimate contralateral strength.

Discussion

Altered perception of contralateral limb strength was commonly observed in the subacute stage of both right and left hemisphere stroke, but altered strength perception was not simply due to anosognosia or neglect. Neither anosognosia nor neglect was common in our sample and neither variable was consistently associated with strength perception. Instead, strength perception was highly correlated with perception of stimulus magnitude and the pattern of association was opposite between patients with right and left stroke. A decreased power function exponent was associated with overestimating contralateral strength in patients with RHLs, whereas an increased exponent was associated with underestimated strength in patients with LHLs. Decreased exponents have been reported for patients with RHLs with neglect3,4 (who often fail to acknowledge contralateral weakness), but the opposite result for patients with LHLs has not been reported previously. While the precise nature of this relationship cannot be determined from this study, it suggests strength perception and magnitude estimation are mediated by the same neural system.5,6 Differences between patients with RHLs and patients with LHLs may either reflect 1) hemispheric specializations for magnitude estimation, such as right hemisphere dominance6; 2) lesion location or volume; or 3) a critical combination of lesion laterality and location as patients with RHLs who overestimated strength frequently had lesions involving the putamen and frontal lobes, whereas patients with LHLs who underestimated strength had lesions involving the thalamus and parietal lobes (Patients LHL4 through LHL6 and RHL7 through RHL11) (table 1) (see also figure E-1 on the Neurology Web site at www.neurology.org). These findings have clinical relevance because overestimating strength can place patients at risk of falls, in which case, rehabilitation can focus on confronting limitations to foster appropriate caution. Conversely, there may be a need to confront doubt about residual ability in patients who underestimate strength to offset despair or frustration. Finally, altered perception of strength and stimulus magnitude following RHLs and LHLs may exist along a continuum of severity, which in extreme cases might help explain the failure of anosognosic and anosodiaphoric patients to acknowledge and appreciate deficits and the exaggerated emotional responses of patients with catastrophic reactions to stroke.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Kenneth Heilman, MD, for suggestions.

Supported by NS39348 (NINDS-NIH), HD40631 (NCMRR-NIH), RR020146 (NCRR-NIH), 5T32HD007420-15 (NICHD-NIH), and The Jackson T. Stephens Spine & Neurosciences Institute.

Footnotes

Additional material related to this article can be found on the Neurology Web site. Go to www.neurology.org and scroll down the Table of Contents for the May 9 issue to find the title link for this article.

References

- 1.Starkstein SE, Federoff JP, Price TR, Leiguarda R, Robinson RG. Anosognosia in patients with cerebrovascular lesions. A study of causative factors Stroke. 1992;23:1446–1453. doi: 10.1161/01.str.23.10.1446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Starkstein SE, Federoff JP, Price TR, Leiguarda R, Robinson RG. Catastrophic reaction after cerebrovascular lesions: frequency, correlates, and validation of a scale. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 1993;5:189–194. doi: 10.1176/jnp.5.2.189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chatterjee A, Dajani BM, Gage RJ. Psychophysical constraints on behavior in unilateral spatial neglect. Neuropsychiatry Neuropsychol Behav Neurol. 1994;7:267–274. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mennemeier M, Pierce CA, Chatterjee A, et al. Biases in attentional orientation and magnitude estimation explain crossover: neglect is a disorder of both. J Cogn Neurosci. 2005;17:1194–1211. doi: 10.1162/0898929055002454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pinel P, Piazza M, LeBihan DL, Dehaene S. Distributed and overlapping cerebral representations of number, size and luminance during comparative judgments. Neuron. 2004;41:983–993. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(04)00107-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Walsh V. A theory of magnitude; common cortical metrics of time, space and quantity. Trends Cogn Sci. 2003;7:483–488. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2003.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Damasio H, Damasio AR. Lesion analysis in neuropsychology. New York: Oxford University Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schenkenberg T, Bradford DC, Ajax ET. Line bisection and unilateral visual neglect in patients with neurologic impairment. Neurology. 1980;30:509–517. doi: 10.1212/wnl.30.5.509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Albert ML. A simple test of visual neglect. Neurology. 1973;23:658–664. doi: 10.1212/wnl.23.6.658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stevens SS, Galanter EH. Ratio scales and category scales for a dozen perceptual continua. J Exp Psychol. 1957;54:377–411. doi: 10.1037/h0043680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.