Abstract

Using cluster-analysis, we investigated whether rational, intuitive, spontaneous, dependent, and avoidant styles of decision making (Scott & Bruce, 1995) combined to form distinct decision-making profiles that differed by age and gender. Self-report survey data were collected from 1,075 members of RAND’s American Life Panel (56.2% female, 18–93 years, Mage = 53.49). Three decision-making profiles were identified: affective/experiential, independent/self-controlled, and an interpersonally-oriented dependent profile. Older people were less likely to be in the affective/experiential profile and more likely to be in the independent/self-controlled profile. Women were less likely to be in the affective/experiential profile and more likely to be in the interpersonally-oriented dependent profile. Interpersonally-oriented profiles are discussed as an overlooked but important dimension of how people make important decisions.

Keywords: decision making, decision-making styles, gender, age differences, cluster analysis

1. Introduction

Individual differences in decision-making styles, such as the tendency to use reason or intuition, are of long-standing interest to psychologists (see Appelt, Milch, Handgraaf, & Weber, 2011 for review). Decision-making styles are associated with job performance (Russ, McNeilly, & Comer, 1996), self-esteem (Thunholm, 2004), planning behaviors (Galotti et al., 2006), and decision-making competence (Bruine de Bruin, Parker, & Fischhoff, 2007; Parker, Bruine de Bruin, & Fischhoff, 2007). Whereas some style measures are context-specific (e.g., career decision making, Harren, 1979), others assess styles across contexts (e.g., Epstein, Pacini, Denes-Raj, & Heier, 1996; Nygren, 2000). The General Decision-Making Styles Inventory (GDMS; Scott & Bruce, 1995) assesses five decision styles of making important decisions—rational, intuitive, spontaneous, avoidant and dependent. Past GDMS research has used a “variable-centered” approach to investigate intercorrelations among items to compute subscales for specific styles, and analyze individual differences in those styles. Here, we use a “person-centered” approach to examine whether certain styles cluster together to form distinct profiles among subgroups of people, by looking at intercorrelations among subscales rather than items (Henry, Tolan, & Gorman-Smith, 2005).

1.1. Decision making

Many theories of decision making distinguish two ways of making decisions (Epstein, 1994; Evans, 2008; Sloman, 1996; Osman, 2004). First, the “affective/experiential” mode is fast and uses gut feelings and experience. Second, the “rational” mode is slower and uses reason and deliberation. Variability in these modes is seen between individuals, depending, for example, on their cognitive ability (Stanovich & West, 2000) and within individuals, such as when the rational mode alters initial intuitions (Kahneman, 2003). Critics of dual-process approaches, however, note that focusing on two modes obscures the complexity of decisional processes (Keren, 2013; Keren & Schul, 2009). Some suggest there is one integrative decision-making process (e.g., Kruglanski & Gigerenzer, 2011), while others argue that decision making involves multiple processes (e.g., Frank, Cohen, & Sanfey, 2009) and is affected by social context (Strough, Karns, & Schlosnagle, 2011).

Drawing from previous decision measures (e.g., career decision-making, Harren, 1979) Scott and Bruce (1995) proposed four decision styles (i.e., rational, intuitive, dependent, and avoidant) which were confirmed, in addition to a fifth style, spontaneous. The rational style involves logical deliberation, matching the “rational” mode of dual-process models. The intuitive style reflects relying on feelings whereas the spontaneous style captures making decisions quickly; both of which match aspects of the affective/experiential mode of dual-process models. Prior work shows that spontaneous and intuitive styles are positively correlated (Baiocco, Laghi, & D’Alessio, 2009; Loo, 2000; Thunholm, 2004), suggesting these two styles may cluster together to form a profile.

The other two styles in Scott and Bruce’s (1995) measure, the dependent (seeking assistance from others) and avoidant styles (postponing decisions) do not conform to a dual-process model. These styles may stand alone in differentiating between people, or they may co-occur with other styles as part of a profile. One study showed a positive association between rational and dependent styles (Loo, 2000), suggesting that people with rational styles may deliberate with others. However, individuals may involve others in the decision-making process for different reasons (see Meegan & Berg, 2002; Strough, Cheng, & Swenson, 2002).

1.2. Aging

Dual-process models of aging and decision making posit that older people rely more on emotions and experience and less on reason than do younger people (Peters, Hess, Västfjäll, & Auman, 2007). Fluid cognitive abilities and working memory that support rational decision making decline in older age (see Babcock & Salthouse, 1990; Verhaeghen, Marcoen, & Goossens, 1993). Emotional and affective skills that support intuition may remain stable or even improve with age (Blanchard-Fields, 2007; Charles & Carstensen, 2010; Kennedy & Mather, 2007). Research investigating age differences in the role of emotions and cognitive ability in decision making yields inconsistencies (see Strough, Parker, & Bruine de Bruine 2015, Mikels, Shuster, & Thai, 2015 for reviews). If older people compensate for age-related cognitive declines by relying more on quick gut reactions, then older age may be associated with a decision-making profile focused on intuition and spontaneity rather than rationality.

However, two studies on age differences in decision styles yield inconsistent findings. Older age in community-dwelling adults was associated with a greater likelihood of reporting both rational and intuitive styles (Bruine de Bruin et al., 2007). For the intuitive style, a study of undergraduates (19–50 years) showed the opposite—older age was associated with reporting a less intuitive style (Loo, 2000). Discrepant findings could reflect differences in samples, with college education affecting the degree to which people rely on rationality and intuition. The current study therefore uses a large, life-span adult sample, in which participants of all ages are recruited in the same way (see Method).

Additionally, research on aging and decision making suggests that age differences in dependent styles are in need of investigation. Older adults (65–94 years) are more likely than younger adults (18–64 years) to report delegating decisions to others (Finucane et al., 2002). However, interviews of older adults (53–84 years old) show that although some prefer family members to make decisions about financial and health plans for them, others want to avoid burdening family (Samsi & Manthorpe, 2011). The personal relevance of decisions may also influence how older adults approach decisions (Hess, 2014).

Dependence on others may increase with age (Strough et al., 2002), as older adults experience a decline in fluid abilities (Salthouse, 2012). If so, depending on others might allow older adults to rely on deliberation, with dependent and rational styles co-occurring in profiles characteristic of older adults. Alternatively, people may depend on others to avoid making decisions themselves. Dependent and avoidant styles are positively correlated in adolescence (Baiocco et al., 2009), but little is known about these styles in older adults because prior research focuses on intuition and reason.

1.3. Gender differences

Gender stereotypes characterize men and women as fundamentally different, even from different “planets” (Gray, 1992). Women are stereotyped as “intuitive” and men as “rational”. However, research investigating gender differences in reports of intuitive and rational decision-making styles yields mixed results. Undergraduate women are more likely than men to report intuitive styles (Sadler-Smith, 2011). Using a mood induction that asked people to describe feelings about winning or losing a competition, women reported using more intuition, and men reported using more reason (Sinclair, Ashkanasy & Chattopadhyay, 2010). However, studies assessing general decision-making styles in age diverse samples do not find significant gender differences (Baiocco et al., 2009; Loo, 2000; Spicer & Sadler-Smith, 2005).

Gender stereotypes characterizing women as interpersonally oriented and men as self-reliant and individualistic (Gilligan, 1982; Tannen, 1991) suggest that men and women differ with the extent that they involve others in decision making (the dependent style). In career decisions, women are more likely than men to endorse relying upon others (Phillips, Pazienza, & Ferrin, 1984). In addition, women are more willing to seek support compared to men (Tamres, Janicki, & Helgeson, 2002; Thoits, 1991). Together, this research suggests that women may be more likely than men to report using an interpersonally-oriented decision-making style.

1.4. Current study

Research Aim 1 is to examine whether decision-making styles form distinct clusters or profiles. Specifically, we examine whether decision-making profiles correspond to using reason versus affect and experience (as dual-process theories posit), as well as advice seeking, or using the dependent style. Research Aim 2 is to investigate age and gender differences in decision profiles.

2. Method

2.1. Participants

Participants were 1,075 members of RAND’s American Life Panel (https://mmicdata.rand.org/alp/) who completed an internet survey (see Table 1 for demographic information). Panelists receive approximately $20 per 30 minutes of survey completion time. Panel members were recruited through random digit dialing for national surveys, including the monthly University of Michigan Consumer Survey. Additional members were recruited via snowball sampling. Panelists without internet access (3.7 %) were provided with access.

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics

| Variable | Descriptive Statistics | Percentage of Sample |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) 2 | Mage= 53.49; Mdnage= 55.00 (SD = 14.85; range 18–93) | |

|

| ||

| Gender | ||

| Males | 43.8 | |

| Females | 56.2 | |

|

| ||

| Ethnicity | ||

| American Indian/Alaskan | 0.7 | |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 2.2 | |

| Black/African American | 7.9 | |

| White/Caucasian | 84.9 | |

| Other | 4.3 | |

|

| ||

| Education | ||

| High school graduate or less | 16.8 | |

| Some college | 23.3 | |

| Associate’s degree | 12.6 | |

| Bachelor’s degree | 27.2 | |

| Graduate degree | 20 | |

|

| ||

| Marital Status | ||

| Married/living with partner | 61.3 | |

| Separated/divorced | 17.4 | |

| Widowed | 6 | |

| Never married | 15.3 | |

2.2. Procedure

Our survey invitation was sent to 1,353 panelists, 1,075 who responded1 (for a 79.5% response rate).

2.3. Measures

2.3.1. Demographics

Participants reported their age (which was entered into the analyses as a continuous variable), as well as their gender, marital status, family income, ethnicity, and highest education attained (see Table 1).

2.3.2. Decision-Making Styles

The 25-item GDMS Inventory (Scott & Bruce, 1995) measured the following styles: rational (e.g. “My decision making requires careful thought”), intuitive (e.g. “When making decisions, I rely upon my instincts”), dependent (e.g. “I rarely make important decisions without consulting other people”), avoidant (e.g. “I postpone decision making whenever possible”), and spontaneous (e.g. “I make quick decisions”). Scott and Bruce (1995) established validity, through factor-analytic procedures, and reliability among four samples (military, young adults, undergraduates, and engineers/technicians; αs = .68-.87). Participants used a 5-point Likert scale (1=strongly disagree to 5=strongly agree) to rate how well statements described how they make “important” decisions (α > .81; see Table 2).

Table 2.

Descriptive Statistics, Correlations, and Coefficient Alpha, for Decision-Making Styles

| Decision-making styles | N | M | SD | Skewness | Kurtosis | α | Correlations | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |||||||

|

|

||||||||||

| 1. Rational | 1065 | 4.17 | 0.68 | −0.86 | 1.41 | 0.84 | ||||

| 2. Intuitive | 1066 | 3.65 | 0.76 | −0.14 | −0.49 | 0.81 | .16** | |||

| 3. Dependent | 1066 | 3.11 | 0.91 | −0.07 | −0.37 | 0.85 | .07* | .01 | ||

| 4. Avoidant | 1066 | 2.12 | 0.87 | 0.73 | 0.16 | 0.86 | -.28** | -.02 | .26** | |

| 5. Spontaneous | 1063 | 2.44 | 0.86 | 0.41 | −0.05 | 0.87 | -.29** | .28** | -.02 | .31** |

Note.

p<.05,

p<.01

2.4. Data Analysis

Analyses were conducted using SPSS 18.0. Table 2 shows descriptive statistics and correlations for the measures of decision styles. We examined skewness and kurtosis and applied transformations as needed. Following Henry et al. (2005), we used a two-step cluster analytic approach. The first step was Ward’s hierarchical cluster analysis which formed clusters by maximizing within-group similarities and between-group differences. Second, a non-hierarchical (K-means) cluster analysis confirmed the hierarchical cluster solution. Cluster solutions were validated by conducting a MANOVA that used the cluster profiles as independent variables, and the five decision-making styles as dependent variables to ensure distinctions between groups (Aldenderfer & Blashfield, 1984). Last, logistic regressions examined age and gender as predictors of profile memberships, controlling for marital status, family income, education, and ethnicity.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Preliminary Analyses

We used logarithmic transformations to correct for skewness and kurtosis of rational and avoidant styles. Correlations among variables were small to moderate (see Table 2); there were no multivariate outliers or multicollinearity issues.

3.2. Decision-Making Style Profiles

The two-step cluster analysis (Henry et al., 2005) identified a 3-cluster solution. A MANOVA found a significant 3-cluster differentiation in the five decision styles, F(5, 1055) = 13,285.54, Wilk’s Λ = 0.450, p <.001. As shown in Table 3, the spontaneous and dependent decision styles were the most distinguished between the clusters.

Table 3.

MANOVA Main Effects with Decision-Making Styles and Profiles

| Decision-Making Styles | F | ηp2 |

|---|---|---|

| Rational | 29.95 | 0.05 |

| Intuitive | 67.69 | 0.11 |

| Dependent | 461.78 | 0.47 |

| Avoidant | 26.83 | 0.05 |

| Spontaneous | 629.55 | 0.54 |

Note. All main effects (df= 2; p<.001).

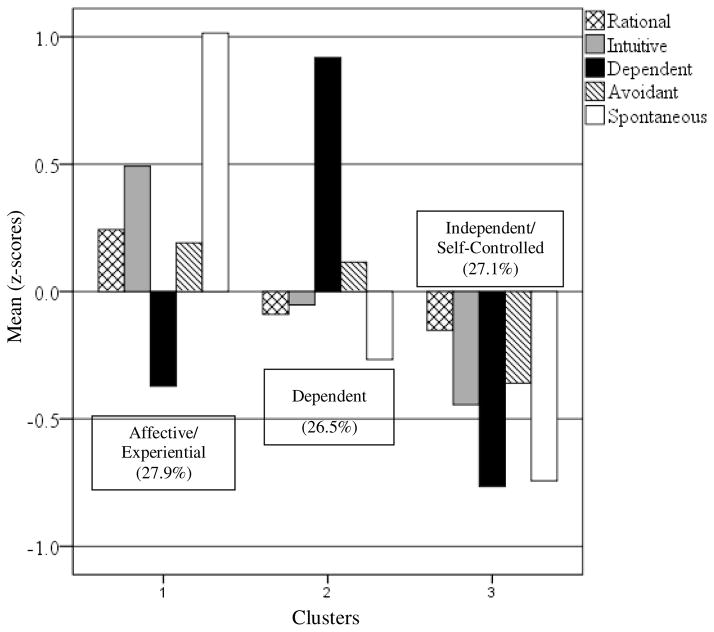

Figure 1 presents the three clusters, in terms of their mean standardized scores on each decision-making style. Cluster 1 corresponded to high use of a spontaneous style and moderately high use of an intuitive style (N= 315, 29.7%). Cluster 2 captured high use of a dependent style and low use of all other styles (N= 281, 26.5%). Cluster 3 (N= 288, 27.1%) represented low endorsement of all styles with the dependent and spontaneous styles the lowest.

Figure 1.

Decision-making style profiles displaying the three different endorsement patterns. Numbers in parentheses indicate the percentage of the sample belonging to each profile.

3.2.1. Decision Profiles Discussion

The first profile matches the idea of the intuitive, fast mode of decision making posited in dual-process models (Epstein, 1994; Evans, 2008; Osman, 2004; Reyna, 2004), and hence we labeled it “affective/experiential.” This profile also shows below-average use of advice or support from others. In contrast, the second profile is defined as using or needing advice and assistance from other people. This profile captures the social context within which decisions occur, with some people preferring to delegate decisions (Finucane et al., 2002; Samsi & Manthrope, 2011), seek advice, and make decisions with others. We labeled this profile “dependent” to match Scott and Bruce’s term for the subscale. Importantly, however, items from the dependent subscale do not distinguish how or why people involve others. For example, using “advice of other people in making important decisions” and “rarely making important decisions without consulting other people” could indicate seeking information from experts to make the “best” decision, or delegating decisions to others due to lack of interest or ability. Hence, the term “interpersonal” might better represent this profile.

Distinguishing characteristics of the third profile are independence from others and a lack of spontaneity—that is, not making decisions driven by quick, affective reactions or consulting others. Hence, we labeled it “independent/self-controlled.” This profile suggests a slow, controlled approach to decision making which is consistent with the deliberative system in dual-process models (Kahneman, 2003; Stanovich & West, 2000). Notably, however, the rational style was not a defining feature of this profile, nor was it well-distinguished across any profile. Hence, this style seems to be less central for differentiating decision-making profiles.

3.3. Aim 2: Age and Gender Differences in Profiles

Three binary logistic regressions were conducted with membership in each decision-making style profile as a discrete outcome variable (0= not in profile, 1= in profile) to assess potential age and gender differences. When entering indicators simultaneously, significant models were found when predicting the affective/experiential, χ2(6)= 31.66, p<.001, R2= .04 (Nagelkerke) and dependent profiles, χ2 (6)= 19.10, p= .004 R2= .02, but not the independent/self-controlled profile, χ2 (6)= 9.78, p=.13, R2= .01.

3.3.1. Age Differences: Results and Discussion

For the affective/experiential profile, age significantly predicted profile membership. Growing older by one year was associated with 2% decreased odds of being in the affective/experiential profile. Although the overall model was not significant, age was a significant predictor of the independent/self-controlled profile. Growing older by one year was associated with 1% increased odds of being in the independent/self-controlled profile (see Table 4).

Table 4.

Binary Logistic Regressions Predicting Profile Membership from Age and Gender

| Predicted Profiles | b (SE) | 95% CI for Odds Ratio |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Odds Ratio | Upper | ||

| Affective/Experiential | ||||

| Included Constant | 0.69(.39) | |||

| Marital Status | 0.05(.05) | 0.955 | 1.05 | 1.150 |

| Household Income | −0.06(.05) | 0.862 | 0.94 | 1.028 |

| Education | −0.28(.14) | 0.572 | 0.76 | 1.004 |

| Ethnicity | −0.02(.07) | 0.854 | 0.99 | 1.136 |

| Age | −0.02(.01)c | 0.973 | 0.98 | 0.992 |

| Gender (0=males, 1=females) | −0.47(.14)c | 0.480 | 0.63 | 0.822 |

|

| ||||

| Dependent | ||||

| Included Constant | −1.15(.39) | |||

| Marital Status | −0.03(.05) | 0.886 | 0.97 | 1.063 |

| Household Income | 0.09(.04)a | 1.006 | 1.09 | 1.190 |

| Education | 0.05(.14) | 0.799 | 1.05 | 1.176 |

| Ethnicity | −0.10(.08) | 0.781 | 0.91 | 1.048 |

| Age | 0.01(.01) | 0.997 | 1.01 | 1.016 |

| Gender | 0.37(.13)b | 1.120 | 1.45 | 1.878 |

|

| ||||

| Independent/Self-Controlled | ||||

| Included Constant | −1.65(.41) | |||

| Marital Status | −0.02(.05) | 0.892 | 0.98 | 1.080 |

| Household Income | −0.04(.05) | 0.881 | 0.96 | 1.052 |

| Education | 0.24(.15) | 0.952 | 1.27 | 1.694 |

| Ethnicity | 0.12(.07) | 0.976 | 1.12 | 1.294 |

| Age | 0.01(.01)a | 1.000 | 1.01 | 1.022 |

| Gender | 0.07(.14) | 0.816 | 1.07 | 1.403 |

Note.

p < .05,

p < .01,

p ≤ .001

Theorists suggest that as people grow older, they shift towards relying more on affect and experience and less on deliberation to make decisions, reflecting age-related declines in fluid cognitive abilities and maintenance or improvement in emotion regulation (e.g., Peters et al., 2007). However, belonging to the affective/experiential profile was less likely with older age. Rather, older age was associated with an increased likelihood of being in the independent/self-controlled profile. Notably, Scott and Bruce’s (1995) inventory asks about “important” decisions. Hess (2014) suggests that older adults apply cognitive resources to personally important decisions. Hence, our findings may reflect that with age, people may be less inclined to make what they see as important decisions quickly and intuitively perhaps due to less time left in life to recover from, say, a bad financial decision.

We did not find a significant association between the dependent profile and age. Previous studies show older adults are more likely to delegate or defer decisions to others (Chen, Ma & Pethtel, 2011; Finucane et al., 2002). Although depending on others and delegating decisions both involve other people, dependence (as measured by GDMS inventory) reflects utilizing others’ advice or obtaining support to make decisions, whereas delegation and deferring reflect not wanting to take responsibility for or postponing decisions. Age may not relate uniformly to various ways people involve others when making decisions. Our findings suggest that obtaining advice from others is important across the life span, not just among older adults.

3.3.2. Gender Differences: Results and Discussion

Significant gender differences were found in two of the three profiles (see Table 4). Females have 37% decreased odds of being in the affective/experiential profile than males, but have 45% increased odds of being in the dependent profile.

Stereotypical views of men and women suggest women use intuition and are interpersonally-oriented whereas men are logical and independent (Gilligan, 1982; Gray, 1992). In contrast to these stereotypes, men were more likely than women to be in the affective/experiential profile. The spontaneous items on Scott and Bruce’s subscale are conceptually similar to items used to measure impulsivity (Parker et al., 2007). Other work suggests that, on average, men tend to engage in more impulsive and risky behaviors than women do (Byrnes, Miller, & Schafer, 1999; Cross, Copping, & Campbell, 2011). Hence, men’s relatively greater likelihood of belonging to the affective/experiential profile may represent a tendency toward greater impulsiveness.

In accord with gender stereotypes, women were more likely than men to belong to the dependent decision-making profile. Women may utilize other people for support and advice when making decisions, similar to how women are more likely than men to use social support as a coping strategy (e.g. Thoits, 1991). However, as discussed earlier, our findings do not address the function of involving others in decision making (getting advice to make the best decision, relying on others to make decisions, delegating decisions to others).

4.1. Limitations and Future Directions

Notable strengths of the current study include a large, national adult life span sample, which addresses limitations from prior research using convenience samples. There are some limitations, however, that should be addressed. First, the generalizability of the profiles is limited by our sample, which included relatively few non-white participants. Second, self-report measures of decision styles may potentially be affected by participants’ concerns about social desirability, and not reflect their actual decision-making performance (see Appelt et al., 2011). Men, for instance, may have rated “interpersonal” items lower because relying on others is inconsistent with masculine gender roles in contemporary US culture. In addition, decision styles assess participants’ perceptions of how they approach decisions, which may not reflect cognitive decision processes. Lastly, our cross-sectional design does not address age changes or cohort differences (Miller, 2007). Cross-sequential designs are necessary to understand within-person changes and historical influences.

Despite these limitations, our findings can inform future research. In terms of individual differences in decision-making profiles, the “fast” versus “slow” distinction (Kahneman, 2011) is not the only important dimension. Although limited by the number of styles measured in the GDMS, our study shows that profiles also vary on the dimension of interpersonal versus individualistic. Future research should focus on disaggregating aspects of the “dependent” profile. A first step would be to distinguish different functions of including others, such as information or advice seeking, compensating for one’s own perceived or actual deficits, or collaborating to make joint decisions (see Meegan & Berg, 2002; Strough et al., 2002). Additional research is necessary to investigate whether focusing on multidimensional profiles (as opposed to styles in isolation) distinguish negative and positive real-world decision outcomes (Bruine de Bruin et al., 2007).

4.2. Conclusions

Individuals’ decision-making approaches are multidimensional. Individuals appear to utilize a composition of styles, rather than solely depending upon one approach when making important decisions. Older adults and women were less likely to be in the affective/experiential decision profile, however, women were also more likely to have an interpersonally-oriented, “dependent” profile. Given the age and gender differences found, researchers should acknowledge how age and gender may influence decision-making processes. Examining how the styles cluster among diverse samples and in relation to real-world outcomes will also enhance our understanding of the complexities associated with decision making.

Highlights.

We report three decision-making profiles identified through cluster analyses.

Older adults were less likely to be in the affective/experiential profile.

Older adults were more likely to be in the independent/self-controlled profile.

Women were less likely to be in the affective/experiential profile.

Women were more likely to be in the interpersonally-oriented dependent profile.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the National Institute on Aging at the National Institutes of Health [P01 AG026571], the National Science Foundation [SES 1459021] and the European Union [FP7-People-2013-CIG-618522]. This report is based on a project conducted by the first author, under the supervision of the second author, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a master’s of science degree at West Virginia University. We thank Barry Edelstein and Melissa Blank, as members of the thesis committee, for their comments on a prior version of this manuscript.

Footnotes

Respondents were more likely than nonrespondents to be male, older, and White (see Bruine de Bruin, Strough, & Parker, 2014 for details).

Percentage of adults in each age group: 18–39 yrs (17.9%), 40–59 yrs (47%), 60–69 yrs (23.4%),70+ yrs (11.7%). In analyses, age was a continuous variable.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Appelt KC, Milch KF, Handgraaf MJ, Weber EU. The Decision Making Individual Differences Inventory and guidelines for the study of individual differences in judgment and decision-making research. Judgment and Decision Making. 2011;6(3):252–262. doi:1011293549. [Google Scholar]

- Aldenderfer MS, Blashfield RK. Cluster Analysis. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage Press; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Babcock RL, Salthouse TA. Effects of increased processing demands on age differences in working memory. Psychology and Aging. 1990;5(3):421–428. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.5.3.421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baiocco R, Laghi F, D’Alessio M. Decision-making style among adolescents: Relationship with sensation seeking and locus of control. Journal of Adolescence. 2009;32(4):963–976. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2008.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanchard-Fields F. Everyday problem solving and emotion. An adult developmental perspective. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2007;16:26–31. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8721.2007.00469.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bruine de Bruin W, Parker AM, Fischhoff B. Individual differences in adult decision-making competence. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2007;92(5):938–956. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.92.5.938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruine de Bruin W, Strough J, Parker AM. Getting older isn’t all that bad: Better decisions and coping when facing ‘sunk costs’. Psychology and Aging. 2014;29:642–647. doi: 10.1037/a0036308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byrnes JP, Miller DC, Schafer WD. Gender differences in risk taking: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin. 1999;125:367–383. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.125.3.367. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Charles S, Carstensen L. Social and emotional aging. Annual Review of Psychology. 2010;61:383–409. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.093008.100448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y, Ma X, Pethtel O. Age differences in trade-off decisions: Older adults prefer choice deferral. Psychology and Aging. 2011;26(2):269–273. doi: 10.1037/a0021582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cross CP, Copping LT, Campbell A. Sex differences in impulsivity: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin. 2011;137(1):97–130. doi: 10.1037/a0021591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epstein S. Integration of the cognitive and the psychodynamic unconscious. American Psychologist. 1994;49(8):709–724. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.49.8.709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epstein S, Pacini R, Denes-Raj V, Heier H. Individual differences in intuitive–experiential and analytical–rational thinking styles. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1996;71(2):390–405. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.71.2.390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans JSB. Dual-processing accounts of reasoning, judgment, and social cognition. Annual Review of Psychology. 2008;59:255–278. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.59.103006.093629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finucane ML, Slovic P, Hibbard JH, Peters E, Mertz CK, MacGregor DG. Aging and decision-making competence: An analysis of comprehension and consistency skills in older versus younger adults considering health-plan options. Journal of Behavioral Decision Making. 2002;15(2):141–164. doi: 10.1002/bdm.40. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Frank MJ, Cohen MX, Sanfey AG. Multiple systems in decision making: A neurocomputational perspective. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2009;18(2):73–77. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8721.2009.01612.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Galotti KM, Ciner E, Altenbaumer HE, Geerts HJ, Rupp A, Woulfe J. Decision-making styles in a real-life decision: Choosing a college major. Personality and Individual Differences. 2006;41(4):629–639. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2006.03.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gilligan C. In a different voice: Psychological theory and women’s development. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Gray J. Men are from Mars, women are from Venus: A practical guide for improving communication and getting what you want in your relationships. New York, NY: Harper Collins; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Harren VA. A model of career decision making for college students. Journal of Vocational Behavior. 1979;14(2):119–133. doi: 10.1016/0001-8791(79)90065-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Henry DB, Tolan PH, Gorman-Smith D. Cluster analysis in family psychology research. Journal of Family Psychology. 2005;19(1):121–132. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.19.1.121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hess TM. Selective engagement of cognitive resources: Motivational influences on older adults’ cognitive functioning. Perspectives on Psychological Science. 2014;9(4):388–407. doi: 10.1177/1745691614527465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahneman D. A perspective on judgment and choice: Mapping bounded rationality. American Psychologist. 2003;58(9):697–720. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.58.9.697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahneman D. Thinking, fast and slow. New York, NY: Macmillan; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Keren G. A tale of two systems a scientific advance or a theoretical stone soup? Commentary on Evans & Stanovich (2013) Perspectives on Psychological Science. 2013;8(3):257–262. doi: 10.1177/1745691613483474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keren G, Schul Y. Two is not always better than one a critical evaluation of two-system theories. Perspectives on Psychological Science. 2009;4(6):533–550. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-6924.2009.01164.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy Q, Mather M. Aging, affect and decision making. In: Vohs KD, Baumeister RF, Loewenstein G, editors. Do emotions help or hurt decision making? A hedgefoxian perspective. New York, NY: Russel Sage Foundation; 2007. pp. 245–265. [Google Scholar]

- Kruglanski AW, Gigerenzer G. Intuitive and deliberate judgments are based on common principles. Psychological Review. 2011;118(1):97. doi: 10.1037/a0020762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loo R. A psychometric evaluation of the General Decision-Making Style Inventory. Personality and Individual Differences. 2000;29(5):895–905. doi: 10.1016/S0191-8869(99)00241-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Meegan SP, Berg CA. Contexts, functions, forms, and processes of collaborative everyday problem solving in older adulthood. International Journal of Behavioral Development. 2002;26:6–15. doi: 10.1080/01650250143000283. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mikels JA, Shuster MM, Thai ST. Aging, emotion, and decision making. In: Hess TM, Strough J, Löckenhoff C, editors. Aging and decision making: Empirical and applied perspectives. New York, NY: Elsevier Inc; 2015. pp. 170–184. [Google Scholar]

- Miller SA. Design. In: Miller SA, editor. Developmental research method. Thousand Oaks, California: Sage Publications; 2007. pp. 30–58. [Google Scholar]

- Nygren TE. Development of a measure of decision making styles. Paper presented at the 72nd annual meeting of the Midwestern Psychological Association; Chicago, IL. 2000. May, [Google Scholar]

- Osman M. An evaluation of dual-process theories of reasoning. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review. 2004;11(6):988–1010. doi: 10.3758/BF03196730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker AM, Bruine de Bruin W, Fischhoff B. Maximizers versus satisficers: Decision-making styles, competence, and outcomes. Judgment and Decision Making. 2007;2:342–350. doi:1010989404. [Google Scholar]

- Peters E, Hess TM, Västfjäll D, Auman C. Adult age differences in dual information processes: Implications for the role of affective and deliberative processes in older adults’ decision making. Perspectives on Psychological Science. 2007;2(1):1–23. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-6916.2007.00025.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips SD, Pazienza NJ, Ferrin HH. Decision-making styles and problem-solving appraisal. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 1984;31(4):497–502. doi: 10.1037/0022-0167.31.4.497. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Reyna VF. How people make decisions that involve risk: A dual-process approach. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2004;13(2):60–66. doi: 10.1111/j.0963-7214.2004.00275.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Russ FA, McNeilly KM, Comer JM. Leadership, decision making and performance of sales managers: A multi-level approach. The Journal of Personal Selling and Sales Management. 1996:1–15. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/40471636.

- Sadler-Smith E. The intuitive style: Relationships with local/global and verbal/visual styles, gender, and superstitious reasoning. Learning and Individual Differences. 2011;21(3):263–270. doi: 10.1016/j.lindif.2010.11.013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Salthouse T. Consequences of age-related cognitive declines. Annual Review of Psychology. 2012;63:201–226. doi: 10.1146/annurev-psych-120710-100328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samsi K, Manthorpe J. ‘I live for today’: a qualitative study investigating older people’s attitudes to advance planning. Health and Social Care in the Community. 2011;19(1):52–59. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2524.2010.00948.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott SG, Bruce RA. Decision-making style: The development and assessment of a new measure. Educational and Psychological Measurement. 1995;55(5):818–831. doi: 10.1177/0013164495055005017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sinclair M, Ashkanasy NM, Chattopadhyay P. Affective antecedents of intuitive decision making. Journal of Management & Organization. 2010;16(3):382–398. doi: 10.5172/jmo.16.3.382. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sloman SA. The empirical case for two systems of reasoning. Psychological Bulletin. 1996;119(1):3–22. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.119.1.3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Spicer DP, Sadler-Smith E. An examination of the general decision-making style questionnaire in two UK samples. Journal of Managerial Psychology. 2005;20(2):137–149. doi: 10.1108/02683940510579777. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stanovich KE, West RF. Individual differences in reasoning: Implications for the rationality debate? Behavioral and Brain Sciences. 2000;23(5):645–665. doi: 10.1017/s0140525x00003435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strough J, Cheng S, Swenson LM. Preferences for collaborative and individual everyday problem solving in later adulthood. International Journal of Behavioral Development. 2002;26(1):26–35. doi: 10.1080/01650250143000337. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Strough J, Karns TE, Schlosnagle L. Decision-making heuristics and biases across the life span. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2011;1235(1):57–74. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2011.06208.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strough J, Parker A, Bruine de Bruin W. Understanding life-span developmental changes in decision-making competence. In: Hess T, Strough J, Löckenhoff C, editors. Aging and decision making: Empirical and applied perspectives. San Diego: Elsevier Academic Press; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Tamres LK, Janicki D, Helgeson VS. Sex differences in coping behavior: A meta-analytic review and an examination of relative coping. Personality and Social Psychology Review. 2002;6(1):2–30. [Google Scholar]

- Tannen D. You just don’t understand: Women and men in conversation. New York: Ballantine Books; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Thoits PA. Gender differences in coping with emotional distress. In: Eckenrode J, editor. The social context of coping. New York: Plenum; 1991. pp. 107–138. [Google Scholar]

- Thunholm P. Decision-making style: Habit, style or both? Personality and Individual Differences. 2004;36(4):931–944. doi: 10.1016/S0191-8869(03)00162-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Verhaeghen P, Marcoen A, Goossens L. Facts and fiction about memory aging: A quantitative integration of research findings. Journals of Gerontology: Psychological Sciences. 1993;48(4):157–171. doi: 10.1093/geronj/48.4.P157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]