Abstract

Objectives

HIV reservoir in the brain represents a major barrier for curing HIV infection. As the most abundant, long-lived cell type, astrocytes play a critical role in maintaining the reservoir; however the mechanism of infection remains unknown. Here, we determine how viral transmission occurs from HIV-infected lymphocytes to astrocytes by cell-to-cell contact.

Design and methods

Human astrocytes were exposed to HIV-infected lymphocytes and monitored by live-imaging, confocal microscopy, transmission and 3-demensional electron microscopy. A panel of receptor antagonists was used to determine mechanism of viral entry.

Results

We found that cell-to-cell contact resulted in efficient transmission of X4- or X4R5-using viruses from T lymphocytes to astrocytes. In co-cultures of astrocytes with HIV-infected lymphocytes, the interaction occurred through a dynamic process of attachment and detachment of the two cell types. Infected lymphocytes invaginated into astrocytes or the contacts occurred via filopodial extensions from either cell type, leading to formation of virological synapses. In the synapses, budding of immature or incomplete HIV particles from lymphocytes occurred directly onto the membranes of astrocytes. This cell-to-cell transmission could be almost completely blocked by anti-CXCR4 antibody and its antagonist, but only partially inhibited by CD4, ICAM1 antibodies.

Conclusion

Cell-to-cell transmission was mediated by a unique mechanism by which immature viral particles initiated a fusion process in a CXCR4-dependent, CD4-independent manner. These observations have important implications for developing approaches to prevent formation of HIV reservoirs in the brain.

Keywords: HIV infection, Cell-to-cell Transmission, Astrocyte, Lymphocyte, Brain, Virological synapse, CXCR4

INTRODUCTION

The report of eradication of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) from an adult patient [1, 2], and long term suppression of HIV without antiretroviral drugs a child born with HIV infection [3, 4] raises hope that we may eventually develop ways to cure HIV infection. However, for such strategies to be successful, it is critical to develop a better understanding of the tissue reservoirs, particularly the brain. In contrast to reservoirs such as spleen, lymph nodes and gut, there are no resident lymphoid cells in the brain. HIV infection is restricted to brain macrophages/microglia and astrocytes [5–7] which are long-lived cells [8–10] where the virus may reside almost indefinitely. Astrocytes can also be infected in vivo by simian and feline immunodeficiency viruses leading to encephalitis [11–13]. Astrocytes are the most abundant cell type in the brain and outnumber neurons 10:1. Infection of a small percentage of astrocytes could result in a sizable reservoir. After the virus establishes latency in astrocytes, exposure to cytokines can result in viral replication without any cytopathic effects[14, 15]. The virus emerging from the infected astrocytes can be transmitted to lymphocytes [16]. In an inflammatory environment, astrocytes may proliferate potentially leading to clonal expansion of HIV in the brain similar to lymphocyte reservoirs [17]. Hence, these cells represent an ideal reservoir for HIV.

However, the mechanism of HIV infection of astrocytes is poorly understood. Although there is strong evidence showing that astrocytes are infected with HIV in vivo [18–22], in vitro studies show that infection with cell-free HIV is extremely inefficient in primary astrocytes [15, 23–25]. Thus there might be other mechanisms in vivo by which HIV infects astrocytes. Astrocytes are an integral part of the blood brain barrier (BBB) and are most commonly infected in the perivascular regions [26], where astrocytes have the potential to be exposed to HIV-infected lymphocytes. Here, we report that infection of astrocytes occurede efficiently by cell-to-cell contact with HIV-infected lymphocytes and demonstrate mechanisms by which this interaction promotes HIV transmission.

METHODS

Primary cells and cell lines

All studies were approved by the Institutional Review Board at the Johns Hopkins University and the Office of Human Subjects Research at the National Institutes of Health (NIH). All brain tissues and blood samples were obtained without identifiers. Astrocytes were cultured from human fetal brain specimens of 10–14 weeks gestation of three different individuals. Individual variability was not determined. Cultures derived from human fetal brain and neural progenitor cells contained >99% astrocytes as determined by immunostaining for glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) and glutamate transporter.

HIV-1 viruses and infection

X4-using full-length HIV-1 infectious clone pNL4-3 was obtained from the NIH AIDS Reagent Program. HIV-1NL4-3 based reporter virus construct, pNLENG1, was made by inserting an EGFP gene linked with internal ribosome entry site between the genes env and nef of pNL4-3 [27]. R5-using HIV-1SF162 based reporter virus, pSF162R3, was constructed in a similar manner [28]. All viral genes including nef are intact in these infectious reporter viruses.

Correlative electron microscopy and three-dimensional electron microscopy

Astrocytes co-cultured with NLENG1-infected JKT cells were fixed after 3 days and processed for transmission electron microscopy (TEM) at the Johns Hopkins University Microscope Facility. One of the samples described above was processed for 3-dimensional electron microscopy (3D-EM) by Renovo Neural Inc.

Infection blocking assay

Antibodies toCD4, CXCR4, DC-Sign, α4β7 integrin and antagonists to CD4 and CXCR4 were used to block cell-to-cell transmission of HIV.

Statistical analysis

Data was analyzed by ANOVA with unequal variance or Student T-test. Dunnett’s method was used for post-hoc test. Shapiro-Wilk test was applied to test normality of the residuals. SAS version 9.2 was used for the above analysis and p<0.05 was used as significance level.

Detailed protocols are described in the Supplemental Information.

RESULTS

Efficient infection of astrocytes occurs in co-cultures with HIV-infected lymphocytes

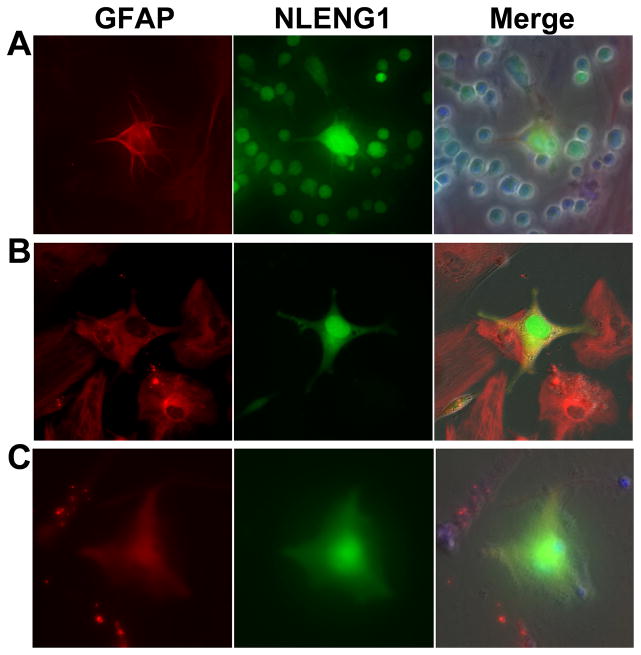

To investigate HIV transmission from lymphocytes to astrocytes, primary human astrocytes were co-cultivated with HIVNL4-3 based reporter virus, NLENG1-infected Jurkat-tat (JKT) cells in the absence of any other treatment (Fig. 1A). Infection of astrocytes appeared 3 days post co-culture. Enhanced green fluorescent protein (EGFP) was distinctly expressed in the entire cytoplasm, all the processes of the infected astrocyte and the nucleus (Fig. 1A–1C). Although astrocyte infection was only ~1%, the actual rate was higher because some of the cells didn’t express EGFP but express HIV-1 p24 (~5%). However, the infection was consistently observed in the co-cultures compared with the absence of visible infection using cell-free HIV alone. Similar rates of infection were seen in both human fetal astrocytes and progenitor-derived astrocytes (PDA); hence, subsequent experiments were performed using human fetal astrocytes.

Figure 1. Infection of astrocytes following the co-cultures with HIV-infected lymphocytes or PBMCs.

HIV infection of astrocytes was observed after 3 days when co-cultured with NLENG1-infected (A) JKT cells, (B) MT4 cells, and (C) PBMCs. GFAP-positive astrocytes: red; NLENG1-infected cells: green. Magnification: 200x.

The infection of astrocytes by cell-cell contact was further verified with other NLENG1-infected lymphocytic cell lines, such as MT4 (Fig. 1B), and peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) (Fig. 1C). And this was also true for other X4- or X4R5-using viruses (Fig. S1). This cell-to-cell transmission was not observed in the co-cultures with R5-using HIVSF162R3-infected PBMCs (data not shown). Therefore, cell-to-cell contact with HIV-infected lymphocytes represents an efficient mechanism for HIV infection of astrocytes.

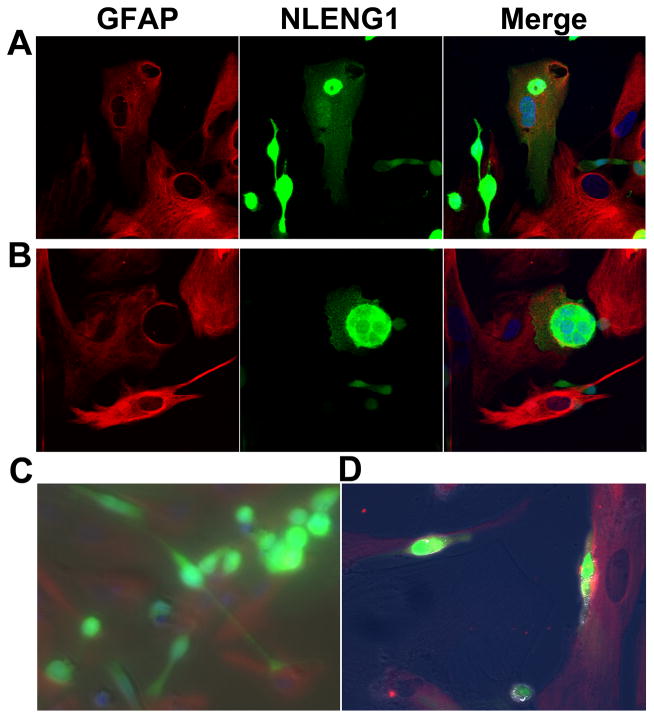

Lymphocytes transmit HIV to astrocytes through a dynamic process of interactions between two types of cells

To study the interactions between lymphocytes and astrocytes in real time, we visualized the co-cultures by time-lapse video microscopy. We observed that lymphocytes frequently made contact with astrocytes, but both cell types were in motion (Movies S1A and S1B). Multiple lymphocytes attached to a single astrocyte and conversely a single lymphocyte made contact with more than one astrocyte. The process of attachment and detachment of lymphocytes to astrocytes was frequently noted in the co-cultures with both uninfected and NLENG1-infected JKT cells (Movies S1A and S1B). However, some lymphocytes remained attached to astrocytes for a long period (Movie S1B), or eventually immobilized on astrocytes resulting in invagination of astrocytes and subsequent HIV infection of astrocytes (Movie S1B, Fig. 2A and S2A). The area of contact between astrocytes and HIV-infected lymphocytes manifested diverse morphological features. In some aggregates, the infected lymphocytes produced processes that spread over the astrocyte surface and formed a large synapse with an interdigitated interface (Fig. 2B and S2B). In others, long processes extended from the infected lymphocytes and made contacts with astrocytes (Fig. 2C). Some intermediary features of contact were seen between these two extremes (Fig. 2D). Thus, HIV transmission from lymphocytes to astrocytes requires active interactions between the two cell types through a dynamic process leading to immobilization of the cells by formation of tight areas of contact.

Figure 2. Interactions of astrocytes with NLENG1-infected JKT cells.

(A) A NLENG1-infected JKT cell (arrow) is shown partially invaginated into an astrocyte resulting in infection with the virus as shown by acquisition of green fluorescence. (B) An astrocyte (arrow head) wrapped around a NLENG1-infected JKT cell (arrow) and a Velcro-like interdigitated interface was formed by processes extending from both cells as shown by an outline. (C) An NLENG1-infected JKT cell made contact with astrocytes by extending long processes (arrow). (D) NLENG1-infected MT4 cells adhered to astrocytes along their entire cell surface (arrow). Magnification: 630x in A and B; 200x in C and D.

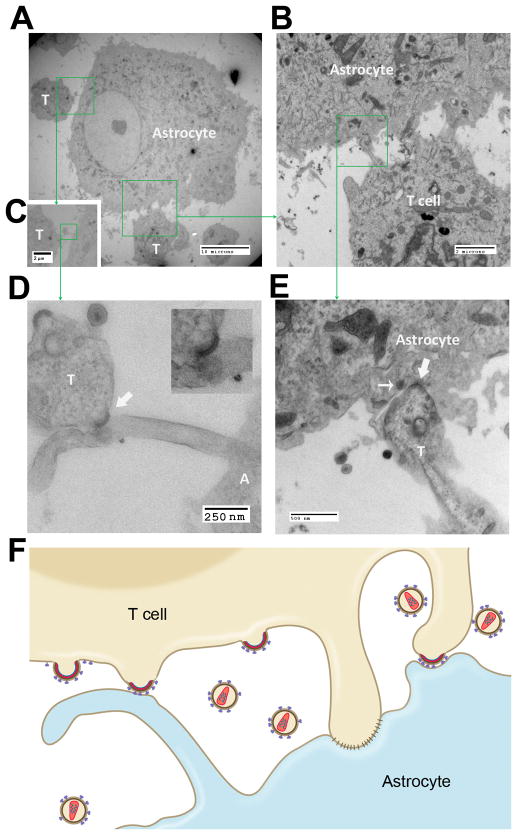

Ultra-structural features of HIV transmission from lymphocytes to astrocytes

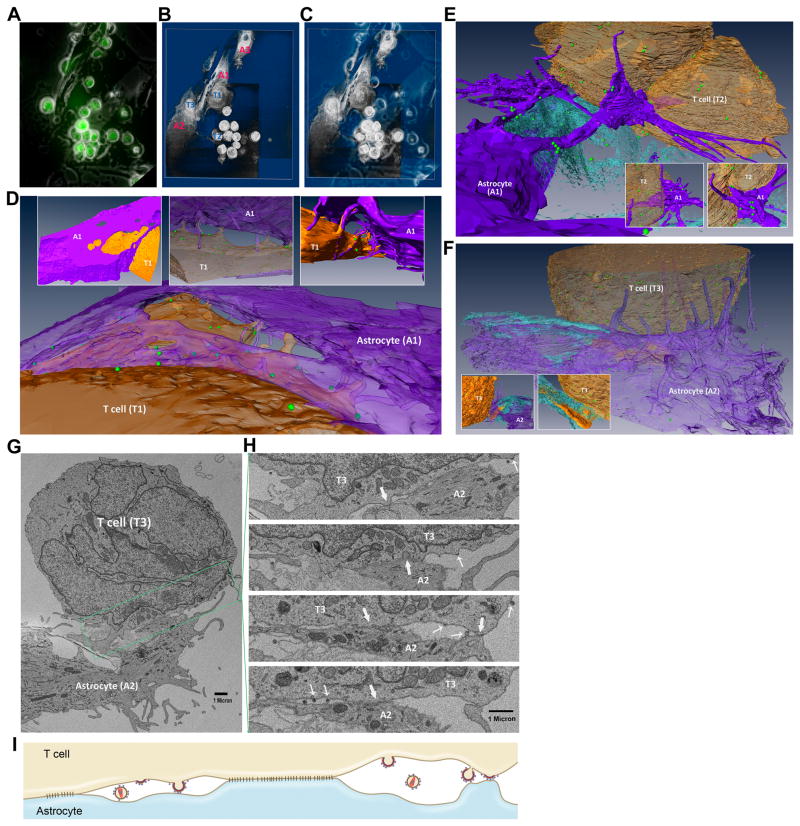

We further characterized ultrastructural features of the contacts between astrocytes and HIV-infected lymphocytes by correlative electron microscopy/3D-EM. Serial blockface scanning EM (SBF-SEM) generated large sets of EM images from the co-culture sample, from which 3D images were reconstructed.

We took phase and fluorescent combined photomicrographs before the samples were processed for EM/3D-EM (Fig. 3A). A 3D-EM image was reconstructed using the described techniques, by which the relationship between astrocytes and T lymphocytes was observed (Fig. 3B and 3C; Movie S2A). From the sets of images, astrocytes (A1 and A2) and lymphocytes (T1–T3) were analyzed by reconstructing high-resolution 3D images to elucidate the mechanisms of HIV transmission from lymphocytes to astrocytes. T1 was an HIV-infected, JKT syncytium confirmed in high-resolution EM images. This cell was partially wrapped by A1, and both T1 and A1 produced processes that stretched out and interdigitated (Fig. 3B and 3D; Movies S2A and S2B). A long process from A1 was seen extending and formed a claw-like structure to grab T2, and many viral particles were seen adherent to these processes suggesting that the processes might aid in the spread of the virus from the lymphocyte to the astrocyte (Fig. 3A–3C, 3E; Mov S2A and S2C). T3 was making contact with A2 and A1, and multiple filopodium-like processes from A02 wrapped around T3 while a single thick process from T3 protruded into A2 (Fig. 3A–3C, 3F; and Movies S2A and S2D).

Figure 3. Interactions between astrocytes and HIV-infected lymphocytes as viewed by correlative 3D electron microscopy.

(A) Fluorescent image with phase exposure was taken prior to processing the sample for EM and 3D EM. HIV-infected JKT cells show green fluorescence. Magnification: 200x. (B) Low-resolution 3D image was re-constructed using SBF-SEM and 3D software. “A” = astrocyte, “T” = T cell. (C) An overlay image of A and B. (D) High-resolution 3D images show that an NLENG1-infected JKT cell, T1 (brown), was partially wrapped by A1 (purple). The villus-like processes from both cells extended and reached the opposite cell, some of which were interdigitated. Inserts above show the views from different angles. (E) Branched processes from A1 (purple) stretched out in a claw-like structure onto T2 (brown). Viral particles were attached to these processes. Inserts at the bottom show the views from different angles. (F) T3 (brown) sited by A2 (purple) which produced processes and wrapped T3. A large filopodium from T3 protruded into A2. Viral particles spread on the astrocyte. Inserts at the bottom show the views of the filopodium from T3 at different angles. (G) A section of SBF-SEM showed multiple areas of the interdigitated contact between the processes from A2 and T3. (H) Serial, discontinuous sections from the boxed region as shown in Fig. 3G were aligned. Multiple tight contacts between the two cells were observed (block arrow) and the viruses from the infected JKT cell were seen budding into intercellular spaces or directly onto the membrane of the astrocyte (thin arrow). (I) Diagram shows that virological synapses are formed and the viral particles are budding between the areas of tight contacts. The immature, budding viral particles make contact with an astrocyte.

In the areas where the cell membranes of A2 and T3 seemed to be in tight opposition (Fig. 3G), serial SBF-SEM images showed that there were multiple small protrusions extending from either of these cells and reaching out to the other cell (Fig. 3Hi–iv). This produced appearance of a Velcro-like structure (Fig. 3Hii) with tight contacts of cell membranes (Fig. 3Hii–iv) interspersed with cleft-like spaces (Fig. 3Hiii and 3H iv). Each individual unit gave the appearance of a virological synapse. Within these synapses, fully mature HIV particles as well as immature viruses that had not been released yet from the lymphocyte membrane were visualized (Fig. 3Hi–iv). Importantly, the viruses were seen budding from the lymphocyte directly onto the astrocyte membrane and making direct contact with the astrocyte membrane (Fig. 3Hiii and 3H iv). The accompanying diagram is a composite of the SBF-SEM images and illustrates this unique phenomenon (Fig. 3I).

A similar mode of HIV transmission from lymphocytes to astrocytes was observed in the context of filopodial extensions by correlative, transmission EM. The processes from HIV-infected lymphocytes were noted making contacts with the astrocyte and forming filopodial connections (Fig. 4A and 4B). The filopodia indented the astrocyte membrane (Fig. 4B) or established contact with an astrocytic process (Fig. 4C and 4D). Viral particles were concentrated and lined up along the filopodia (Fig. 4B and 4E). At the sites of contacts between the lymphocyte filopodia and the astrocyte membrane, crescent-shaped hyperdensities protruded from the lymphocyte membranes suggested budding of the viruses (Fig. 4D and 4E). These immature or incomplete viral particles made direct contact with the astrocyte membrane. A diagram representing a composite of these photomicrographs illustrates the mode of HIV cell-to-cell transmission (Fig. 4F).

Figure 4. Filopodial extensions and HIV budding onto the membrane of astrocytes.

(A) Bridge-like structures were observed between an astrocyte and HIV-infected JKT cells. Magnification: 2,500x. (B) Tight connections were seen at the contact sites of the bridge-like processes between the astrocyte and the bottom lymphocyte in (A). Viral particles were seen attached to the cell membrane and processes of the astrocyte. Magnification: 20,000x. (C) A bridge was formed between the processes from the astrocyte and the upper-left lymphocyte in A. Magnification: 2,500x. (D) A budding virus interacted with an astrocyte process (block arrow) from C. Magnification: 50,000x. The insert shows the site of contact of the budding virus with the astrocyte. Magnification: 80,000x. (E) A bridge in D was further magnified (50,000x). A budding virus was seen inside the virological synapse and made a tight contact with the astrocyte membrane (block arrow). Another mature viral particle was also docked on the astrocyte membrane inside the synapse (thin arrow). (F) The diagram is a composite of the above photomicrographs, depicting the areas of tight contacts between the two types of cells with immature viral particles that directly bud onto the astrocyte membrane.

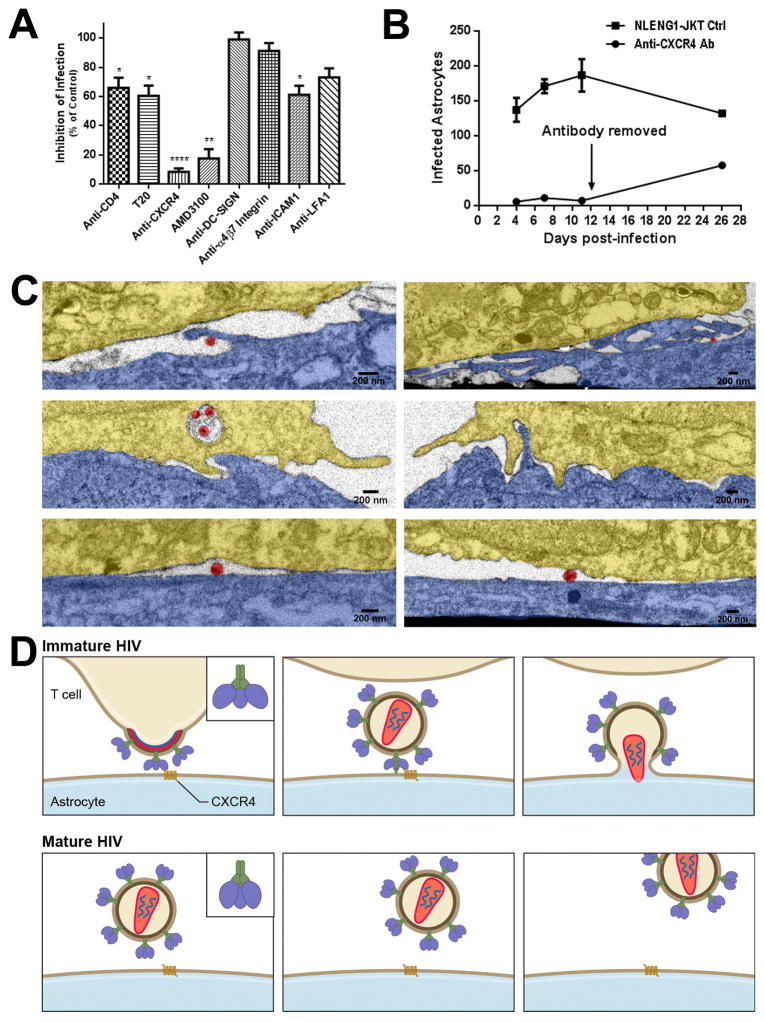

Role of HIV receptors and adhesion molecules in cell-to-cell transmission of HIV from lymphocytes to astrocytes

To further elucidate the mechanism for cell-to-cell transmission of HIV from lymphocytes to astrocytes, a series of blocking assays were performed using specific antibodies or pharmacological antagonists. We found that anti-CXCR4 antibody almost completely blocked this transmission (Fig. 5A). However, the continuous presence of anti-CXCR4 antibody was necessary, since removing the antibody resulted in an increased number of infected astrocytes (Fig. 5B). Similarly, a CXCR4 antagonist, ADM3100, significantly inhibited cell-to-cell infection of astrocytes. However, there was no effect of anti-CXCR4 antibody on the infection with cell-free HIV in astrocytes (Fig. S3). Anti-CD4 antibody and CD4 fusion inhibitor, T-20, partially abolished cell-to-cell infection in astrocytes (Fig. 5A). In contrast, antibodies to DC-sign and α4β7 integrin had no effect on this cell-to-cell infection (Fig. 5A). Anti-ICAM1 and anti-LFA1 antibodies partially inhibited this cell-to-cell infection (Fig. 5A). Taken together, CXCR 4 is a primary receptor for HIV entry into astrocytes in the context of cell-to-cell infection.

Figure 5. Chemokine receptor, CXCR4, mediates cell-to-cell transmission of HIV from lymphocytes to astrocytes.

(A) HIV cell-to-cell transmission was significantly blocked by both anti-CXCR4 antibody (20 μg/ml) and CXCR4 antagonist AMD3100 (40–100 μM), and partially inhibited by anti-CD4 antibody (20 μg/ml) and fusion inhibitor T20 (100–500 nM) as well as anti-ICAM1 and anti-LFA1 antibodies (20 μg/ml). There was no inhibition with antibodies to DC-SIGN (20 μg/ml) and α4β7 integrin (30ug/ml). The results were the average of 3–5 experiments, shown as mean ± SEM. * p<0.05, ** p<0.01, **** p<0.0001. (B) The blocking of HIV infection of astrocytes by anti-CXCR4 could be partially reversed after the antibody was removed from the co-culture. (C) Astrocytes were pretreated with antibodies to CD4 or CXCR4 (20 μg/ml each) or control media for 1 hr; antibodies were maintained in the co-cultures with NLENG1-infected JKT cells for 24 hr before fixing and processing for correlative IA-SEM. Membrane protrusions from astrocytes toward JKT membranes were absent in the co-cultures with anti-CXCR4 antibody, but present in the controls and the ones with anti-CD4 antibody. Two images for each treatment were from two independent experiments. Colors in images: astrocyte: blue; HIV-infected JKT cell: gold; and HIV virion: red. (D) A hypothesis is proposed based on the ultrastructural observations and the inhibition of CXCR4 on the transmission of HIV from lymphocytes to astrocytes. The CXCR4-binding sites on the surface of the envelope of budding or immature HIV is in an “open” state which allows the virus to directly bind to CXCR4 on the membrane of astrocytes, and hidden following a conformational change that is triggered during HIV maturation. However, the pre-bound virus would trigger the fusion process of HIV envelope with the astrocyte membrane while the maturation is completed, leading to HIV transmission from lymphocytes to astrocytes. This process cannot occur with cell-free mature HIV in astrocytes that lack CD4 expression since the CXCR4-binding sites are hidden in the envelope of mature HIV particles.

Furthermore, the focused ion beam -SEM/3D study showed that the contact zones between astrocytes and HIV-infected T cells had a smooth configuration in the co-cultures treated with anti-CXCR4 antibody for one day. However, membrane extensions from astrocytes lined with HIV were observed in the co-cultures free of antibody or treated with anti-CD4 antibody (Fig. 5C), indicating that anti-CXCR4 antibody might inhibit the formation of filopodia from astrocytes. Thus, CXCR4 possibly plays a dual role in mediating HIV transmission to astrocytes from the infected lymphocytes.

To determine if the CXCR4-mediated transmission of HIV from lymphocytes to astrocytes may be due to an aberrant mutation in the envelope leading to a conformational change, we sequenced the env gene of NLENG1. No mutations were found in the gp120 region compared to the parental NL4-3.

Based on these observations, a novel mechanism is proposed for cell-to-cell transmission of HIV from lymphocytes to astrocytes, by which the budding or immature virus with “open” CXCR4-binding sites on the envelope might bind directly to CXCR4 on the astrocyte membrane and trigger the process of fusion during HIV maturation (Fig. 5D). However, the mature HIV particle cannot gain entry into an astrocyte without expressing the CD4 receptor.

Infection of astrocytes may be associated with migration of HIV-infected lymphocytes into the brain

HIV infection of astrocytes occurs primarily in the perivascular regions of the brain. For this infection to occur, the infected lymphocytes need to either cross the BBB or engage them across the endothelial tight junctions. Hence, we used an in vitro BBB model to determine if HIV-infected T lymphocytes can cross the BBB and monitored their response to specific chemokines. A significant amount of NLENG1-infected JKT cells migrated across the BBB in the presence of SDF-1α (150 ng/ml) (p<0.05 for 1 day, p<0.001 for 2 days). In comparison, no significant migration was noted with RANTES at the same concentration (Fig. S4A). When the transwell inserts were examined by confocal microscopy, cell-to-cell contacts were frequently observed between NLENG1-infected JKT cells and astrocytes in the presence of SDF1α (Fig. S4B), but less frequently with RANTES (Fig. S4C). Since chemokine SDF-1α is a ligand of CXCR4, this suggest that CXCR4 plays a central role in cell-to-cell interaction and HIV transmission from lymphocytes to astrocytes.

DISCUSSION

Multiple studies show HIV infection of astrocytes in vivo in adults and children [18–22, 29]. These cells are predominantly infected in the perivascular regions and the number of infected cells correlates with the presence of HIV dementia and encephalitis [26]. However, in vitro studies show a very low infectivity of astrocytes with cell-free virus [15, 23, 24]. Because astrocytes do not express detectable levels of CD4 on their membranes [30, 31], cell-free virus enters astrocytes via endocytosis and becomes trapped and degraded in endosomes/lysosomes [25]. This barrier can be overcome by transfection of astrocytes with HIV proviral DNA [32, 33] or by infection with pseudotyped viruses [25, 34]. HIV can infect astrocytes when the cells are co-cultured with HIV-infected lymphocytes [35, 36]; however, the mechanisms of these interactions are poorly understood. Here, we show that co-culturing astrocytes with HIV-infected lymphocytes overcame the barrier of infection with cell-free virus. This cell-to-cell transmission was observed in X4- or X4R5-using viruses. Considering that HIV transmission in lymphocytes by cell-to-cell contact is 3–5 orders of magnitude more efficient than the infection with cell-free virus [37–39], cell-to-cell infection could be an important mechanism for HIV infection of astrocytes in vivo.

HIV-infected lymphocytes could make multiple dynamic contacts with astrocytes. A key ultrastructural observation was the direct budding of incomplete viral particles from the lymphocyte membrane onto the astrocyte membrane, such that these immature viruses were in contact with the astrocyte membrane while still connected to the lymphocyte. Such interactions were mainly seen in virological synapses with two types of distinct structures. The first type of synapse was observed in the Velcro-like structures where clefts were surrounded by tight membrane junctions formed by the two type cells. This synapse is clearly different from other forms of virological synapses described in HIV transmission between lymphocytes or from dendritic cells to lymphocytes; and viral transmission from lymphocytes or dendritic cells to lymphocytes is CD4 and coreceptor-dependent [40–43]. The differences between interactions of lymphocyte-lymphocyte, dendritic cell-lymphocyte and lymphocyte-astrocyte were recently published [44]. Another type of structure was seen at the contact interfaces between the astrocyte membrane and the filopodial extension tips from the infected lymphocytes, where the viruses were observed budding onto the astrocyte membrane. These observations indicate that cell-to-cell infection might occur before complete formation or detachment of HIV particles from the donor lymphocytes, which establishes a unique mechanism of HIV transmission from lymphocyte to astrocyte.

X4-tropic HIV uses CXCR4 as a co-receptor which is abundantly expressed on the astrocyte membrane [45]. We found that blockade of CXCR4 completely abolished HIV transmission in the co-cultures. Previous studies implicated a number of receptors in HIV infection of astrocytes with cell-free virus, but the role of CXCR4 has not been investigated [30, 46–49]. Our results indicate that cell-to-cell contact could result in a change in HIV receptor utilization for viral entry in astrocytes. Based on the observation that HIV directly budded onto the astrocyte membrane, we hypothesize that the CXCR4-binding sites on the envelope of immature HIV might be exposed and accessible for its binding to CXCR4 independent of CD4. Studies show that immature viral particles are resistant to fusion with target cells and thus not infectious until undergoing a proteolytic maturation to form a functional core [50–52]. The immature virus contains a highly stable spherical Gag lattice and the process of maturation may trigger a conformational change in the ectodomain of the envelope complex leading to its conversion into a fusion-competent state [50, 53]. Typically, the envelope protein binds to CD4 inducing a conformational change in gp120, by which the exposed epitopes bind to CXCR4 [54]. However, it is possible that gp120 in the immature virus may be in a conformational state that allows it to bind to CXCR4 independent of CD4. In the co-culture, the immature viruses that have not completely detached from the cell membrane would have the opportunity to bind to CXCR4 and then trigger viral entry while completing maturation. This may be a key factor in HIV transmission from lymphocytes to astrocytes. These observations are also consistent with a recent study of SHIV-infected macaques showing the expansion of CD4 independent virus with infection of astrocytes [55].

Importantly, CXCR4 can be up-regulated by cytokines IL-1β, IFN-γ and TNF-α [56, 57], and these pro-informatory cytokines are markedly elevated in the brain of patients with HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders [58, 59]. This is consistent with the observation that HIV infection of astrocytes is more abundant in the later stages of HIV infection [26], which is also the stage when X4-using virus appears [60]. In contrast, we did not observe any significant infection of astrocytes co-cultured with R5-using virus-infected PBMCs, likely because astrocytes express very low level of CCR5 compared to abundant CXCR4. Although autopsy studies show that most HIV strains isolated from the brain are R5-using viruses [7, 61], some studies have reported X4- or R5X4-using HIV-1 from the brain or CSF of patients with HIV-associated dementia [7, 62, 63] and some R5X4 viruses preferentially use CXCR4 for entry [7, 63]. In one study, both R5 and X4 viruses were found in CSF of selected patients while only R5 virus was present in the blood suggesting autonomous CSF viral evolution [64]. CXCR4-using SHIVs have also been shown to cause an encephalitis in rhesus macaques [65]. Anti-retroviral therapy induces HIV to switch from co-receptor CCR5 to CXCR4 usage and this switch may appear later in the CNS compartment compared to the periphery [66]. In general, a switch from R5 to R5X4 or X4 is associated with acceleration of disease progression [60].

Studies show that CD4 and adhesion molecules (LFA-1, ICAM-1) contribute to cell-to-cell transmission of HIV between lymphocytes [39–41]. Since astrocytes do not express CD4 [30, 31], it is interesting that a partial blockade with anti-CD4 antibody was noted in the co-cultures. It is possible that a trans-receptor mechanism may contribute to viral entry into astrocytes, by which CD4 expressed on neighboring cells primes HIV envelope protein to fuse with a target cell that expresses appropriate co-receptors [67]. Another possibility is that astrocytes may express very low level of CD4 since CD4 mRNA can be detected in astrocytes [68]. ICAM-1 expression can be up-regulated upon activation by pro-inflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α, IL-1β, IFN-γ and HIV proteins gp120 [69, 70]. Adhesion molecules contributed to HIV transmission from lymphocytes to astrocytes because they can promote cell-to-cell contact.

Lymphocytes migrate into the brain [71] with a frequency that is significantly higher in asymptomatic carriers [71, 72]. Lymphocyte infiltration is also observed in SIV/FIV-infected animal models [73, 74]. Because HIV-1-infected and/or immune activated macrophages produce IL-1β, secretion of SDF-1 from astrocytes is further induced [75]. We found that SDF-1 significantly triggered the migration of HIV-infected lymphocytes through the BBB. This may explain the predominance of HIV-infected astrocytes in the perivascular compartment [26].

In conclusion, the virus is transmitted from lymphocytes to astrocytes via a mechanism by which the immature virus buds from the lymphocyte membrane and binds to CXCR4 directly and triggers the fusion process in a CD4-independent manner post-viral maturation. This could be a major mechanism for HIV entry into other cells with co-receptor expression and extremely low or no CD4 expression [76–78]. CXCR4 also plays a critical role in the migration of lymphocytes across the BBB and in the formation of cellular processes from astrocytes that engage HIV-infected lymphocytes. Hence, CXCR4 may be a therapeutic target to prevent formation of an HIV reservoir in astrocytes.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by NIMH P30 Pilot Award (G L) and the NINDS intramural funds. We thank David Levy at the New York University and Amanda Brown at the Johns Hopkins University (JHU) for providing HIV-1 reporter viruses NLENG1 and SF162R3, respectively; Michael Delannoy at the JHU Microscope Facility, Andrew Roholt at Renovo Neural Inc. and Sriram Subramaniam and Lesley Earl at the NCI for correlative EM and 3D EM; Joseph Steiner and Suneil Hosmane at the JHU for time-lapse imaging; Alan Hoofring at NIH for editing pictures, movies and cartoons and Tianxia Wu for statistical analysis.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

GL conceived the project, conducted experiments, analyzed data and wrote the manuscript. CA, LJ and TD conducted experiments and analyzed data. EO helped with conceptual design and provided logistical support. AN conceived the project, analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript.

References

- 1.Hutter G, Nowak D, Mossner M, Ganepola S, Mussig A, Allers K, et al. Long-term control of HIV by CCR5 Delta32/Delta32 stem-cell transplantation. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:692–698. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0802905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Allers K, Hutter G, Hofmann J, Loddenkemper C, Rieger K, Thiel E, et al. Evidence for the cure of HIV infection by CCR5Delta32/Delta32 stem cell transplantation. Blood. 2011;117:2791–2799. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-09-309591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Persaud D, Gay H, Ziemniak C, Chen YH, Piatak M, Jr, Chun TW, et al. Absence of detectable HIV-1 viremia after treatment cessation in an infant. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:1828–1835. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1302976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tobin NH, Aldrovandi GM. Are Infants Unique in Their Ability to be “Functionally Cured” of HIV-1? Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. 2014;11:1–10. doi: 10.1007/s11904-013-0189-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kramer-Hammerle S, Rothenaigner I, Wolff H, Bell JE, Brack-Werner R. Cells of the central nervous system as targets and reservoirs of the human immunodeficiency virus. Virus Res. 2005;111:194–213. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2005.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Churchill M, Nath A. Where does HIV hide? A focus on the central nervous system. Curr Opin HIV AIDS. 2013;8:165–169. doi: 10.1097/COH.0b013e32835fc601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dunfee R, Thomas ER, Gorry PR, Wang J, Ancuta P, Gabuzda D. Mechanisms of HIV-1 neurotropism. Curr HIV Res. 2006;4:267–278. doi: 10.2174/157016206777709500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hickey WF. Basic principles of immunological surveillance of the normal central nervous system. Glia. 2001;36:118–124. doi: 10.1002/glia.1101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lassmann H, Schmied M, Vass K, Hickey WF. Bone marrow derived elements and resident microglia in brain inflammation. Glia. 1993;7:19–24. doi: 10.1002/glia.440070106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McCarthy GF, Leblond CP. Radioautographic evidence for slow astrocyte turnover and modest oligodendrocyte production in the corpus callosum of adult mice infused with 3H-thymidine. J Comp Neurol. 1988;271:589–603. doi: 10.1002/cne.902710409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gavrilin MA, Mathes LE, Podell M. Methamphetamine enhances cell-associated feline immunodeficiency virus replication in astrocytes. J Neurovirol. 2002;8:240–249. doi: 10.1080/13550280290049660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Overholser ED, Coleman GD, Bennett JL, Casaday RJ, Zink MC, Barber SA, et al. Expression of simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV) nef in astrocytes during acute and terminal infection and requirement of nef for optimal replication of neurovirulent SIV in vitro. J Virol. 2003;77:6855–6866. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.12.6855-6866.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Thompson KA, Varrone JJ, Jankovic-Karasoulos T, Wesselingh SL, McLean CA. Cell-specific temporal infection of the brain in a simian immunodeficiency virus model of human immunodeficiency virus encephalitis. J Neurovirol. 2009;15:300–311. doi: 10.1080/13550280903030125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tornatore C, Nath A, Amemiya K, Major EO. Persistent human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection in human fetal glial cells reactivated by T-cell factor(s) or by the cytokines tumor necrosis factor alpha and interleukin-1 beta. J Virol. 1991;65:6094–6100. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.11.6094-6100.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sabri F, Tresoldi E, Di Stefano M, Polo S, Monaco MC, Verani A, et al. Nonproductive human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection of human fetal astrocytes: independence from CD4 and major chemokine receptors. Virology. 1999;264:370–384. doi: 10.1006/viro.1999.9998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chauhan A, Mehla R, Vijayakumar TS, Handy I. Endocytosis-mediated HIV-1 entry and its significance in the elusive behavior of the virus in astrocytes. Virology. 2014;456–457:1–19. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2014.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Maldarelli F, Wu X, Su L, Simonetti FR, Shao W, Hill S, et al. HIV latency. Specific HIV integration sites are linked to clonal expansion and persistence of infected cells. Science. 2014;345:179–183. doi: 10.1126/science.1254194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tornatore C, Chandra R, Berger JR, Major EO. HIV-1 infection of subcortical astrocytes in the pediatric central nervous system. Neurology. 1994;44:481–487. doi: 10.1212/wnl.44.3_part_1.481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ranki A, Nyberg M, Ovod V, Haltia M, Elovaara I, Raininko R, et al. Abundant expression of HIV Nef and Rev proteins in brain astrocytes in vivo is associated with dementia. Aids. 1995;9:1001–1008. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199509000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Takahashi K, Wesselingh SL, Griffin DE, McArthur JC, Johnson RT, Glass JD. Localization of HIV-1 in human brain using polymerase chain reaction/in situ hybridization and immunocytochemistry. Ann Neurol. 1996;39:705–711. doi: 10.1002/ana.410390606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.An SF, Groves M, Gray F, Scaravilli F. Early entry and widespread cellular involvement of HIV-1 DNA in brains of HIV-1 positive asymptomatic individuals. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 1999;58:1156–1162. doi: 10.1097/00005072-199911000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Anderson CE, Tomlinson GS, Pauly B, Brannan FW, Chiswick A, Brack-Werner R, et al. Relationship of Nef-positive and GFAP-reactive astrocytes to drug use in early and late HIV infection. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol. 2003;29:378–388. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2990.2003.00475.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McCarthy M, He J, Wood C. HIV-1 strain-associated variability in infection of primary neuroglia. J Neurovirol. 1998;4:80–89. doi: 10.3109/13550289809113484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Di Rienzo AM, Aloisi F, Santarcangelo AC, Palladino C, Olivetta E, Genovese D, et al. Virological and molecular parameters of HIV-1 infection of human embryonic astrocytes. Arch Virol. 1998;143:1599–1615. doi: 10.1007/s007050050401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vijaykumar TS, Nath A, Chauhan A. Chloroquine mediated molecular tuning of astrocytes for enhanced permissiveness to HIV infection. Virology. 2008;381:1–5. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2008.07.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Churchill MJ, Wesselingh SL, Cowley D, Pardo CA, McArthur JC, Brew BJ, et al. Extensive astrocyte infection is prominent in human immunodeficiency virus-associated dementia. Ann Neurol. 2009;66:253–258. doi: 10.1002/ana.21697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Levy DN, Aldrovandi GM, Kutsch O, Shaw GM. Dynamics of HIV-1 recombination in its natural target cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:4204–4209. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0306764101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Brown A, Gartner S, Kawano T, Benoit N, Cheng-Mayer C. HLA-A2 down-regulation on primary human macrophages infected with an M-tropic EGFP-tagged HIV-1 reporter virus. J Leukoc Biol. 2005;78:675–685. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0505237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nuovo GJ, Gallery F, MacConnell P, Braun A. In situ detection of polymerase chain reaction-amplified HIV-1 nucleic acids and tumor necrosis factor-alpha RNA in the central nervous system. Am J Pathol. 1994;144:659–666. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ma M, Geiger JD, Nath A. Characterization of a novel binding site for the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 envelope protein gp120 on human fetal astrocytes. J Virol. 1994;68:6824–6828. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.10.6824-6828.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Peudenier S, Hery C, Ng KH, Tardieu M. HIV receptors within the brain: a study of CD4 and MHC-II on human neurons, astrocytes and microglial cells. Res Virol. 1991;142:145–149. doi: 10.1016/0923-2516(91)90051-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dewhurst S, Sakai K, Bresser J, Stevenson M, Evinger-Hodges MJ, Volsky DJ. Persistent productive infection of human glial cells by human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and by infectious molecular clones of HIV. J Virol. 1987;61:3774–3782. doi: 10.1128/jvi.61.12.3774-3782.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shahabuddin M, Volsky B, Kim H, Sakai K, Volsky DJ. Regulated expression of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 in human glial cells: induction of dormant virus. Pathobiology. 1992;60:195–205. doi: 10.1159/000163723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Canki M, Thai JN, Chao W, Ghorpade A, Potash MJ, Volsky DJ. Highly productive infection with pseudotyped human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) indicates no intracellular restrictions to HIV-1 replication in primary human astrocytes. J Virol. 2001;75:7925–7933. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.17.7925-7933.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Brack-Werner R, Kleinschmidt A, Ludvigsen A, Mellert W, Neumann M, Herrmann R, et al. Infection of human brain cells by HIV-1: restricted virus production in chronically infected human glial cell lines. Aids. 1992;6:273–285. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nath A, Hartloper V, Furer M, Fowke KR. Infection of human fetal astrocytes with HIV-1: viral tropism and the role of cell to cell contact in viral transmission. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 1995;54:320–330. doi: 10.1097/00005072-199505000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dimitrov DS, Willey RL, Sato H, Chang LJ, Blumenthal R, Martin MA. Quantitation of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection kinetics. J Virol. 1993;67:2182–2190. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.4.2182-2190.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sourisseau M, Sol-Foulon N, Porrot F, Blanchet F, Schwartz O. Inefficient human immunodeficiency virus replication in mobile lymphocytes. J Virol. 2007;81:1000–1012. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01629-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chen P, Hubner W, Spinelli MA, Chen BK. Predominant mode of human immunodeficiency virus transfer between T cells is mediated by sustained Env-dependent neutralization-resistant virological synapses. J Virol. 2007;81:12582–12595. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00381-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jolly C, Mitar I, Sattentau QJ. Adhesion molecule interactions facilitate human immunodeficiency virus type 1-induced virological synapse formation between T cells. J Virol. 2007;81:13916–13921. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01585-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rudnicka D, Feldmann J, Porrot F, Wietgrefe S, Guadagnini S, Prevost MC, et al. Simultaneous cell-to-cell transmission of human immunodeficiency virus to multiple targets through polysynapses. J Virol. 2009;83:6234–6246. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00282-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hubner W, McNerney GP, Chen P, Dale BM, Gordon RE, Chuang FY, et al. Quantitative 3D video microscopy of HIV transfer across T cell virological synapses. Science. 2009;323:1743–1747. doi: 10.1126/science.1167525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Felts RL, Narayan K, Estes JD, Shi D, Trubey CM, Fu J, et al. 3D visualization of HIV transfer at the virological synapse between dendritic cells and T cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:13336–13341. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1003040107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Do T, Murphy G, Earl LA, Del Prete GQ, Grandinetti G, Li GH, et al. Three-dimensional imaging of HIV-1 virological synapses reveals membrane architectures involved in virus transmission. J Virol. 2014;88:10327–10339. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00788-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rezaie P, Trillo-Pazos G, Everall IP, Male DK. Expression of beta-chemokines and chemokine receptors in human fetal astrocyte and microglial co-cultures: potential role of chemokines in the developing CNS. Glia. 2002;37:64–75. doi: 10.1002/glia.1128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Harouse JM, Bhat S, Spitalnik SL, Laughlin M, Stefano K, Silberberg DH, et al. Inhibition of entry of HIV-1 in neural cell lines by antibodies against galactosyl ceramide. Science. 1991;253:320–323. doi: 10.1126/science.1857969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hao HN, Lyman WD. HIV infection of fetal human astrocytes: the potential role of a receptor-mediated endocytic pathway. Brain Res. 1999;823:24–32. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(98)01371-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Liu Y, Liu H, Kim BO, Gattone VH, Li J, Nath A, et al. CD4-independent infection of astrocytes by human immunodeficiency virus type 1: requirement for the human mannose receptor. J Virol. 2004;78:4120–4133. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.8.4120-4133.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Deiva K, Khiati A, Hery C, Salim H, Leclerc P, Horellou P, et al. CCR5-, DC-SIGN-dependent endocytosis and delayed reverse transcription after human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection in human astrocytes. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2006;22:1152–1161. doi: 10.1089/aid.2006.22.1152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Joyner AS, Willis JR, Crowe JE, Jr, Aiken C. Maturation-induced cloaking of neutralization epitopes on HIV-1 particles. PLoS Pathog. 2011;7:e1002234. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wyma DJ, Kotov A, Aiken C. Evidence for a stable interaction of gp41 with Pr55(Gag) in immature human immunodeficiency virus type 1 particles. J Virol. 2000;74:9381–9387. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.20.9381-9387.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Murakami T, Ablan S, Freed EO, Tanaka Y. Regulation of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Env-mediated membrane fusion by viral protease activity. J Virol. 2004;78:1026–1031. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.2.1026-1031.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Pang HB, Hevroni L, Kol N, Eckert DM, Tsvitov M, Kay MS, et al. Virion stiffness regulates immature HIV-1 entry. Retrovirology. 2013;10:4. doi: 10.1186/1742-4690-10-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Berson JF, Doms RW. Structure-function studies of the HIV-1 coreceptors. Semin Immunol. 1998;10:237–248. doi: 10.1006/smim.1998.0130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zhuang K, Leda AR, Tsai L, Knight H, Harbison C, Gettie A, et al. Emergence of CD4 independence envelopes and astrocyte infection in R5 simian-human immunodeficiency virus model of encephalitis. J Virol. 2014;88:8407–8420. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01237-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Croitoru-Lamoury J, Guillemin GJ, Boussin FD, Mognetti B, Gigout LI, Cheret A, et al. Expression of chemokines and their receptors in human and simian astrocytes: evidence for a central role of TNF alpha and IFN gamma in CXCR4 and CCR5 modulation. Glia. 2003;41:354–370. doi: 10.1002/glia.10181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Gabuzda D, Wang J. Chemokine receptors and mechanisms of cell death in HIV neuropathogenesis. J Neurovirol. 2000;6 (Suppl 1):S24–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Yao H, Bethel-Brown C, Li CZ, Buch SJ. HIV neuropathogenesis: a tight rope walk of innate immunity. J Neuroimmune Pharmacol. 2010;5:489–495. doi: 10.1007/s11481-010-9211-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Shapshak P, Duncan R, Minagar A, Rodriguez de la Vega P, Stewart RV, Goodkin K. Elevated expression of IFN-gamma in the HIV-1 infected brain. Front Biosci. 2004;9:1073–1081. doi: 10.2741/1271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Weinberger AD, Perelson AS. Persistence and emergence of X4 virus in HIV infection. Math Biosci Eng. 2011;8:605–626. doi: 10.3934/mbe.2011.8.605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Peters PJ, Duenas-Decamp MJ, Sullivan WM, Brown R, Ankghuambom C, Luzuriaga K, et al. Variation in HIV-1 R5 macrophage-tropism correlates with sensitivity to reagents that block envelope: CD4 interactions but not with sensitivity to other entry inhibitors. Retrovirology. 2008;5:5. doi: 10.1186/1742-4690-5-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ohagen A, Devitt A, Kunstman KJ, Gorry PR, Rose PP, Korber B, et al. Genetic and functional analysis of full-length human immunodeficiency virus type 1 env genes derived from brain and blood of patients with AIDS. J Virol. 2003;77:12336–12345. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.22.12336-12345.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Gorry PR, Bristol G, Zack JA, Ritola K, Swanstrom R, Birch CJ, et al. Macrophage tropism of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 isolates from brain and lymphoid tissues predicts neurotropism independent of coreceptor specificity. J Virol. 2001;75:10073–10089. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.21.10073-10089.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Spudich SS, Huang W, Nilsson AC, Petropoulos CJ, Liegler TJ, Whitcomb JM, et al. HIV-1 chemokine coreceptor utilization in paired cerebrospinal fluid and plasma samples: a survey of subjects with viremia. J Infect Dis. 2005;191:890–898. doi: 10.1086/428095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Buch S, Sui Y, Dhillon N, Potula R, Zien C, Pinson D, et al. Investigations on four host response factors whose expression is enhanced in X4 SHIV encephalitis. J Neuroimmunol. 2004;157:71–80. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2004.08.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Vissers M, Stelma FF, Koopmans PP. Could differential virological characteristics account for ongoing viral replication and insidious damage of the brain during HIV 1 infection of the central nervous system? J Clin Virol. 2010;49:231–238. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2010.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Speck RF, Esser U, Penn ML, Eckstein DA, Pulliam L, Chan SY, et al. A trans-receptor mechanism for infection of CD4-negative cells by human immunodeficiency virus type 1. Curr Biol. 1999;9:547–550. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(99)80241-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Boutet A, Salim H, Taoufik Y, Lledo PM, Vincent JD, Delfraissy JF, et al. Isolated human astrocytes are not susceptible to infection by M- and T-tropic HIV-1 strains despite functional expression of the chemokine receptors CCR5 and CXCR4. Glia. 2001;34:165–177. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Lee SJ, Benveniste EN. Adhesion molecule expression and regulation on cells of the central nervous system. J Neuroimmunol. 1999;98:77–88. doi: 10.1016/s0165-5728(99)00084-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Dietrich JB. The adhesion molecule ICAM-1 and its regulation in relation with the blood-brain barrier. J Neuroimmunol. 2002;128:58–68. doi: 10.1016/s0165-5728(02)00114-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Petito CK, Adkins B, McCarthy M, Roberts B, Khamis I. CD4+ and CD8+ cells accumulate in the brains of acquired immunodeficiency syndrome patients with human immunodeficiency virus encephalitis. J Neurovirol. 2003;9:36–44. doi: 10.1080/13550280390173391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Kibayashi K, Mastri AR, Hirsch CS. Neuropathology of human immunodeficiency virus infection at different disease stages. Hum Pathol. 1996;27:637–642. doi: 10.1016/s0046-8177(96)90391-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Czub S, Muller JG, Czub M, Muller-Hermelink HK. Nature and sequence of simian immunodeficiency virus-induced central nervous system lesions: a kinetic study. Acta Neuropathol. 1996;92:487–498. doi: 10.1007/s004010050551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Ryan G, Grimes T, Brankin B, Mabruk MJ, Hosie MJ, Jarrett O, et al. Neuropathology associated with feline immunodeficiency virus infection highlights prominent lymphocyte trafficking through both the blood-brain and blood-choroid plexus barriers. J Neurovirol. 2005;11:337–345. doi: 10.1080/13550280500186445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Peng H, Erdmann N, Whitney N, Dou H, Gorantla S, Gendelman HE, et al. HIV-1-infected and/or immune activated macrophages regulate astrocyte SDF-1 production through IL-1beta. Glia. 2006;54:619–629. doi: 10.1002/glia.20409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Hesselgesser J, Horuk R. Chemokine and chemokine receptor expression in the central nervous system. J Neurovirol. 1999;5:13–26. doi: 10.3109/13550289909029741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Wiley CA, Schrier RD, Nelson JA, Lampert PW, Oldstone MB. Cellular localization of human immunodeficiency virus infection within the brains of acquired immune deficiency syndrome patients. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1986;83:7089–7093. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.18.7089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Willey SJ, Reeves JD, Hudson R, Miyake K, Dejucq N, Schols D, et al. Identification of a subset of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1), HIV-2, and simian immunodeficiency virus strains able to exploit an alternative coreceptor on untransformed human brain and lymphoid cells. J Virol. 2003;77:6138–6152. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.11.6138-6152.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.