Abstract

Background. Falciparum malaria is an important pediatric infectious disease that frequently affects pregnant women and alters infant morbidity. However, the impact of some prenatal and perinatal risk factors such as season and intermittent preventive treatment during pregnancy (IPTp) on neonatal susceptibility has not been fully elucidated.

Methods. A cohort of 415 infants born to women who were positive and negative for malaria was monitored in a longitudinal study in Southwestern Cameroon. The clinical and malaria statuses were assessed throughout, whereas paired maternal-cord and 1-year-old antimalarial antibodies were assayed by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. Infant susceptibility to malaria was ascertained after accounting for IPTp and season in the statistical analysis.

Results. Malaria prevalence was higher in women (P = .039) who delivered during the rainy season and their infants (P = .030) compared with their dry season counterparts. Infants born to women who were positive for malaria (6.40 ± 2.83 months) were older (P = .028) than their counterparts who were negative for malaria (5.52 ± 2.85 months) when they experienced their first malaria episode. Infants born in September–November (adjusted odds ratio [OR] = 0.31, 95% confidence interval [CI] = 0.13–0.72) and to mothers on 1 or no IPTp-sulfadoxine/pyrimethamine (SP) dose (adjusted OR = 0.51, 95% CI = 0.28–0.91) were protected, whereas those born in the rainy season (adjusted OR = 2.82, 95% CI = 1.21–6.55) were susceptible to malaria.

Conclusions. Intermittent preventive treatment during pregnancy and month of birth have important implications for infant susceptibility to malaria, with 2 or more IPTp-SP dosage possibly reducing immunoglobulin M production.

Keywords: antibodies, infant susceptibility, IPTp, malaria, pregnancy, season

Falciparum malaria is the most important pediatric infectious disease in sub-Saharan Africa, where it is estimated to kill mainly children less than 5 years of age [1]. Pregnant women constitute a major risk group, partly due to the transient depression of cell-mediated immunity that allows fetal allograft retention but interferes with resistance to infectious diseases [2]. With at least 50 million mothers at risk annually [3], malaria in pregnancy (MiP) due to Plasmodium falciparum, represents a major public health burden [4, 5].

Although newborns in areas of high malaria transmission are relatively protected from malaria in early life [6], the time to first malaria infections and the intensity of symptoms vary among infants [4, 7]. Identifying the factors underlying these differential susceptibilities is critical for malaria control in this vulnerable group. Reports indicate that MiP affects symptomatic infant morbidity, although its exact role remains unknown. Although studies have documented increased susceptibility to malaria [4, 7–10] and nonmalarial fevers [11] in infants born to mothers with P falciparum infection at delivery, others [12, 13] have reported improved resistance to malaria in infancy.

The administration of intermittent preventive treatment during pregnancy (IPTp) with at least 2 therapeutic doses of sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine (SP) [14] has been shown to be effective in reducing malaria-associated adverse events [15, 16] and placental infection in the study area [17]. Nevertheless, the reduction in exposure to P falciparum might affect exposure intensity in utero, interfere with the development of malaria-specific immunity [18], and consequently alter infant susceptibility to malaria. However, little is known about the potential effect of IPTp on maternal and fetal immunity [19] and neonatal susceptibility to disease.

In spite of the high seasonality of malaria transmission in the study area [20–22], its impact on placental malaria (PM), pregnancy outcome, and newborns’ susceptibility has not been fully elucidated. The effect of some risk factors on the infant's antibody profile and their susceptibility to malaria is poorly understood. In this study, the clinical and malaria status of infants was assessed from birth to 12 months, in an attempt to evaluate the relationship between perinatal (season and month of birth) and prenatal (maternal malaria, IPTp, maternal- cord antibodies at parturition) risk factors on the infants’ antibodies and malaria susceptibility. Knowledge of the immune mechanisms underlying changes in susceptibility may have implications, not only for the understanding of human malaria immunobiology but also for the evaluation of future vaccine efficacy in this age group.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Ethics Statement

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Buea, whereas administrative authorization was obtained from the South West Regional Delegation of Public Health. Written informed consent was obtained from all the study participants. We followed the US Department of Health and Human Services Human Experimentation guidelines throughout the study.

Study Area

The study was conducted in the Mutengene Health Centre from June 2008 to July 2010. Mutengene is a semiurban setting located at approximately 220 m along the slope of Mount Cameroon in the South West region. The population of the area is highly heterogeneous, consisting of individuals from almost all the ethnic groups of Cameroon and some parts of neighboring Nigeria [20, 21]. The climate consists of a short dry season (December–February) and long rainy season (March–November), whose peak period (June–August) is interspersed by early moderate (March–May) and late moderate (September–November) rains. The minimal temperature varies between 18°C in August to 20°C in December, whereas maximal temperature ranges from 30°C in March to 35°C in February [20]. Malaria transmission is perennial but especially intense during the rainy season. Anopheles gambiae, Anopheles Funetus, and Anopheles Hancocki are the main vectors with the highest infectivity rate (entomological inoculation rate = 9.3%) in the region. Plasmodium falciparum, the predominant parasite species, accounts for up to 96.0% of malaria infections [20]. Intermittent preventive treatment during pregnancy with SP from 4 months was implemented in Mutengene since 2006, in line with the World Health Organization guidelines for the delivery of IPTp at each scheduled visit after “quickening” (16 weeks) to ensure that a high proportion of women receive a minimum of 2 doses of IPT [14].

Study Population and Sample Survey

Volunteer mothers who had been resident in the study area for at least 2 years were enrolled through a cross-sectional survey during the third trimester (≥35 weeks) of gestation at the antenatal clinic (ANC) in the health center. A standard questionnaire was used to document information relating to maternal age, last menstrual period, gravidity, parity, gestational age, history of fever attack during gestation, use of IPTp- sulfadoxine/pyrimethamine (SP) and dosage as well as infant birth weight and Apgar score at enrollment, and delivery from ANC cards, patient's medical record book, and health center maternal care register. The cohort of newborns was then evaluated through a longitudinal, community-based approach during the first year of life.

Sample Collection at Delivery

Blood samples (3–5 mL) were collected from the umbilical cord at delivery in the health center and from the mother by venipucture within 24 hours of parturition for parasitological, hematological, and immunological analysis. After the delivery of the placenta, a piece (5 × 5 × 2 cm) was excised from the paracentric area [17].

Longitudinal Surveys

The health status of the infants was monitored bimonthly at home using a structured morbidity questionnaire, and febrile infants (axillary temperature >37.5°C) were clinically examined and treated at the health center. Finger prick blood samples were collected from all febrile infants for hemoglobin (Hb) and malaria parasitemia determination. An episode of malaria was defined as fever and presence of malaria parasites. Infants presenting with acute malaria were given Artesunate-Lumefantrine, the first-line combination currently recommended for use in the treatment of uncomplicated malaria in Cameroon. Infants with severe malaria were treated using a uniform protocol based on standard recommendations [23] consisting of parenteral quinine at 20 mg/kg loading dose followed by 10 mg/kg maintenance dose every 12 hours for 3 days.

Scheduled clinic visits were also undertaken on a quarterly basis from birth until 1 year. During such visits, infants were clinically examined and anthropometric measurements and axillary temperature were recorded. Finger prick blood samples were then collected for parasitological and hematological analyses. At 1 year of age, venous blood (3–5 mL) was also collected for analysis.

Malaria Parasitemia Determination

This test was done using thin and thick smears of maternal and cord blood stained with 10% Giemsa (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) as well as in placental impressions and biopsies as described previously [17]. The malaria parasitemia status and density were determined under oil immersion with the 100 × objective, 10 × eyepiece of a binocular Olympus microscope, whereas the Plasmodium species was identified on the thin blood smear fixed for 10 seconds in methanol prior to staining. A smear was only considered negative if no malaria parasites were seen in 50 high-power fields. Freshly collected placenta biopsies were fixed in 10% neutral-buffered formalin for a maximum of 3 months, embedded in paraffin wax, sectioned, and then stained with hematoxylin and eosin. Impression smears and biopsies were examined for malaria parasites and pigments using polarized light microscopy at × 1000, and the infection was classified as active or past based on the presence of parasites in erythrocytes or malaria pigment in fibrin or monocyte/macrophage, respectively [24]. Placental histological sections were examined without knowledge of peripheral blood film and impression smear results. Overall, a mother was considered positive for malaria parasite at delivery if any parasites or malaria pigments were seen in a peripheral blood, placental blood, or tissue.

Hematological Analysis

Hemoglobin concentrations were determined at delivery (maternal and cord), during morbidity visits (if axillary temperature ≥37.5°C), and during quarterly clinic visits using a hemoglobinometer (HemoCue, Angelholm, Sweden). Anemia was defined as Hb <11.0 g/dL and further classified as severe (Hb <5 g/dL), moderate (Hb <7.0, 7.0–10.0 g/dL), and mild (Hb >10.0–11.0 g/dL) [22]. Ferrous sulphate syrup was given to all children with Hb <10 g/dL, per Integrated Management of Childhood Illness guidelines.

Hemoglobin Genotyping

Infant Hb genotype was determined by cellulose acetate electrophoresis using packed red cells. The AA, AS, and SS genotypes were deduced by comparison to positive controls run alongside the samples in an electric field (350 V) for 25 minutes.

Antibody Measurement

Paired maternal cord and 1-year infant plasma samples were assayed for P falciparum-specific antibodies of the immunoglobulin (Ig)G, IgG1, IgG2, IgG3, IgG4, IgE, and IgM isotypes by indirect enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). All antibodies were measured using an extract of (schizont-enriched) blood-stage parasites (F32) as the capture antigen [25], and goat antihuman-IgG (Sigma-Aldrich) was used as capture antibody. From checkerboard titrations, it was determined that the optimal concentration for coating plates with the antigen for all isotypes or subclasses was 10 µg/mL.

Each test plasma was screened at a 1:1000 for IgG, 1:20 for IgG2/IgG4, and 1:40 dilution for IgG1/IgG3, with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) containing 0.5% (v/v) Tween 20, 20% sodium azide, and 0.5% bovine serum albumin (BSA) as the diluent.

For the ELISA, the microtiter plates (Costar, Cambridge, MA) were incubated overnight at 4°C with the crude antigen in carbonate buffer (50 µL/well) and then blocked for 2 hours at 37°C, with PBS containing 0.5% BSA. Duplicate wells were subsequently incubated for 1 hour at 37°C, with 50 µL diluted test plasma/well, washed, and then probed with the relevant isotype-specific antiserum-conjugated to alkaline phosphatase (ALP) (Mabtech, Sweden). The IgG2-4 assays were enhanced using biotinylated mouse anti-human IgG and then ALP-conjugated streptavidin (Mabtech, Stockholm) as described elsewhere [26]. After incubation with the ALP conjugates, paranitrophenol phosphate (Sigma-Aldrich) was added as substrate before the optical density at 405 nm of each well was read on an ELISA plate reader (Tecan, Menlo Park, CA). In each assay, test samples giving optical densities (OD) that exceeded the corresponding mean + 2 standard deviation for 25 nonimmune European donors were considered seropositive for the antibody.

Statistical Analyses

All data were analyzed using SPSS Statistics 20 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL). Antibody OD were log transformed before analysis. The significance of differences in prevalence and seropositivity were explored using the Pearson's χ2 test, whereas the differences in group means were assessed using Student t test or analyses of variance. Association analysis of clinical episodes and risk factors was undertaken by logistic regression. A P value ≤.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Four hundred forty-two volunteer pregnant women were enrolled into the study (Table 1). However, maternal cord blood and placental biopsies were only collected for 415 women due to voluntary termination, referral before or after delivery due to complications, prompt discharge, and change of hospital. An additional 16 cord blood samples could not be analyzed due to clotting. Two hundred eighty-three infants successfully completed the follow-up, and loss to follow-up was mainly due to relocation of parents, voluntary termination of participation, and death.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of the Placental Malaria-Positive and Malaria-Negative Parturient Mothers and Their Infants From Mutengene, South Western Cameroonaa

| Parameter | Subclass | % of Study Participants (n) | Maternal Malaria Status |

P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Positive | Negative | ||||

| Maternal Characteristics (Mean ± SD) | |||||

| Age (years) | 100 (415) | 23.8 ± 5.4 (166) | 24.2 ± 5.1 (247) | .472 | |

| Hb (g/dL) | 99.0 (411) | 10.5 ± 1.8 (165) | 10.9 ± 1.7 (246) | .046 | |

| Maternal characteristics, % (n) | |||||

| Age group (years) | ≤20 | 28.3 (117) | 45.3 (53) | 54.7 (64) | .382 |

| 21–35 | 68.0 (281) | 38.4 (108) | 61.6 (173) | ||

| >35 | 3.6 (15) | 33.3 (5) | 66.7 (10) | ||

| Gravidity | Primigravid | 32.0 (132) | 46.2 (61) | 53.8 (71) | .231 |

| Secundigravid | 27.4 (113) | 37.2 (42) | 62.8 (71) | ||

| Multigravid | 40.1 (168) | 37.5 (63) | 62.5 (105) | ||

| IPTp-SP Usage | Yes | 92.2 (379) | 39.6 (150) | 60.4 (229) | .347 |

| No | 7.8 (32) | 48.5 (16) | 51.5 (17) | ||

| IPTp-SP Dosage | One or less | 41.4 (170) | 41.2 (70) | 58.8 (100) | .720 |

| Two or more | 58.6 (241) | 39.4 (95) | 60.6 (146) | ||

| History of Fever | Yes | 50.6 (207) | 43.0 (89) | 57.0 (118) | .268 |

| No | 49.4 (202) | 37.6 (76) | 62.4 (126) | ||

| Anemia Status | Anemic | 50.4 (207) | 45.4 (94) | 54.6 (113) | .028 |

| Nonanemic | 49.6 (204) | 34.8 (71) | 65.2 (133) | ||

| Infant characteristics, mean ± SD (n) | |||||

| Birth weight (g) | 99.8 (414) | 3214 ± 574 (166) | 3353 ± 542 (248) | .014 | |

| Apgar | 97.8 (406) | 8.95 ± 1.0 (162) | 9.10 ± 0.9 (244) | .126 | |

| Cord Hb (g/dL) | 88.2 (366) | 15.5 ± 2.1 (146) | 15.4 ± 2.1 (220) | .674 | |

| Infant characteristics [% (n)] | |||||

| Low birth weight (<2500 g) | 5.6 (23) | 65.2 (15) | 34.8 (8) | .012 | |

| Anemia status | Anemic | 1.6 (6) | 16.7 (1) | 83.3 (5) | .233 |

| Nonanemic | 98.4 (360) | 40.3 (145) | 59.7 (215) | ||

| Gender | Male | 47.2 (195) | 40.0 (78) | 60.0 (117) | .939 |

| Female | 52.8 (218) | 40.4 (88) | 59.6 (130) | ||

| Hb genotype | AA | 83.6 (235) | 42.6 (100) | 57.4 (135) | .466 |

| AS | 15.4 (43) | 44.2 (19) | 55.8 (24) | ||

| SS | 0.7 (2) | 0.0 (0) | 100.0 (2) | ||

| Season of birth | Rainy | 79.7 (314) | 42.7 (134) | 57.3 (180) | .039 |

| Dry | 20.3 (80) | 30.0 (24) | 70.0 (56) | ||

| Month of birth | Mar–May | 25.1 (99) | 61.6 (61) | 38.4 (38) | <.001 |

| Jun–Aug | 39.3 (155) | 38.1 (59) | 61.9 (96) | ||

| Sep–Nov | 21.6 (85) | 21.2 (18) | 78.8 (67) | ||

| Dec–Feb | 14.0 (55) | 36.4 (20) | 63.6 (35) | ||

Abbreviations: Hb, hemoglobin; IPTp, intermittent presumptive treatment for malaria during pregnancy; SD, standard deviation; SP, sulfadoxine/pyrimethamine; AA, normal Hb; AS, sickle cell trait; SS, sickle cell disease.

a Values in parentheses denote total participants with valid values for this variable. A mother was considered positive for malaria parasite at delivery if any parasites or malaria pigment were seen in a peripheral blood, placental blood, or tissue; The possible association between maternal malaria prevalence with age groups, gravidity, anemia status, reported fever history, IPTp-SP dosage, birth weight category, gender, Hb genotype, season of birth, and period of birth were explored using the Pearson's χ2 test, whereas the differences in mean age, Hb level, birth weight, and Apgar between malaria-positive and malaria-negative women were assessed using the Student t test. Bold text indicate significant P values.

Basic Characteristics of Malaria-Positive and Malaria-Negative Women

The mean age of the mothers was 24.05 ± 5.2 (range, 15–41) years. Most of the women were between 21 and 35 years old, multigravida, and had taken at least 2 doses of IPTp-SP (Table 1). Cord blood malaria parasitemia was rare because it was only detected in 1.5% (6 of 399) of study participants. The most sensitive method for the determination of maternal malaria infection was placenta histology with a malaria parasite prevalence of 37.2 (141 of 379). Maternal peripheral malaria parasitemia screens could only detect 7.5% (30 of 400), and placenta impressions detected only 15% (62 of 352), suggesting that some infected mothers could not be detected with these methods. Overall, active maternal malaria parasite infection at delivery was detected in 40.2% (166 of 415) of the study women, whereas active plus past infection prevalence was 62.7% (259 of 413).

The proportion of women with malaria was higher (P = .039) in the rainy season (42.7%) compared to the dry season (30.0%); the March–May (61.6%) was higher (P < .001) than other months. Anemic mothers were also more (P = .028) malaria positive (45.4%) compared with their nonanemic counterparts (34.8%). Twelve women (5.8%) had severe anemia, 97 (46.9%) had moderate anemia, and 98 (47.3%) had mild anemia. Women who were positive for malaria also had lower Hb levels (P = .046) and lower birth weight babies (P = .014) compared with their negative counterparts (Table 1).

Most of the infants were born in the rainy season (79.7%), during the months of June–August (39.3%). The proportion of low birth weight (5.6%), anemia (1.6%), and sickle cell disease (0.7%) in neonates was quite low. The proportion of infants with low birth weight (65.2%) and delivered in the rainy season (42.7%) from March to May (61.6%) was higher in malaria-positive women compared with their negative counterparts. However, there was no association between maternal malaria status and infant Hb genotype.

Incidence of Malaria Infections Among Study Infants During Their First Year of Life

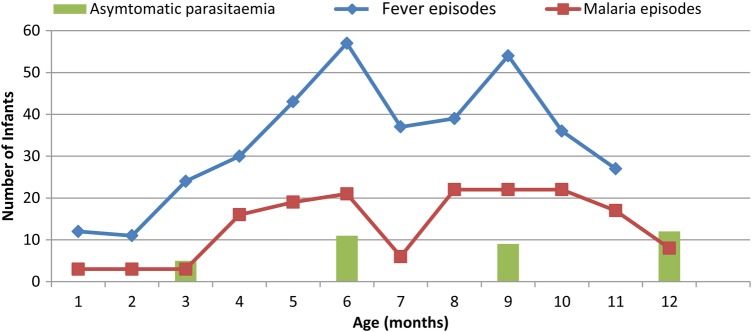

One hundred twenty-six (44.5%) infants who completed the survey experienced at least 1 episode of malaria. Malaria incidence in infants was recorded from the 1st to the 12th month, although they were most vulnerable between 4 and 11 months (Figure 1). The mean number of malaria attacks per infant per year was 0.66 ± 0.91. The mean ages and relative incidence of malaria in the infants are shown in Table 2. Although these sick infants tended to be more from mothers without PM (46.5%) compared with their PM-positive counterparts (41.9%), there was no significant (P = .265) association between PM at delivery and infant susceptibility to malaria during the first year of life. Infants born to PM-positive women were older (P = .028) than their PM-negative counterparts when they experienced their first malaria episode (Table 3). The age of first malaria episode also varied (P = .006) with month of birth.

Figure 1.

Relative morbidity of 283 infants from Mutengene, South Western Cameroon within the first year of life. Asymptomatic parasitemia was only assessed during the quarterly surveys, whereas fever and malaria episodes were recorded throughout the morbidity visits to the health center.

Table 2.

Malaria Parasitemia Prevalence and Mean (±Standard Deviation [SD]) Age (Months) of the Study Infants According to Frequency of Fever Attacks During the First Year of Life

| Frequency of Morbidity | No. of Infants | Malaria Parasitemia Prevalence (%) | Age (Months) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean ± SD | Range | |||

| 1 | 162 | 59.3 | 6.47 ± 2.84 | 0–12 |

| 2 | 75 | 57.3 | 7.80 ± 2.22 | 1–12 |

| 3 | 34 | 64.7 | 9.70 ± 1.86 | 5–12 |

| 4 | 8 | 50.0 | 11.20 ± 0.86 | 10–12 |

Table 3.

Effect of Perinatal and Prenatal Risk Factors on Infant Susceptibility to Fever and Malaria in the First Year of Lifea

| Parameter | Subclass | AFFA (Months) |

Prevalence of Malaria Episodes |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean ± SD (n) | P Value | % (n) | Unadjusted P Value |

OR | 95% CI | Adjusted P Value |

||

| Maternal characteristics | ||||||||

| Age group (years) | ≤20 | 5.4 ± 2.8 (57) | .213 | 38.7 (29) | .223 | 0.55 | 0.21–1.44 | .224 |

| 21–25 | 6.3 ± 3.0 (71) | 42.1 (45) | 0.53 | 0.26–1.10 | .087 | |||

| >25 | 5.9 ± 2.8 (86) | 51.0 (51) | REF | |||||

| Gravidity | Primigravidae | 5.8 ± 2.9 (63) | .638 | 40.9 (36) | .717 | 1.47 | 0.60–3.60 | .402 |

| Secundigravidae | 5.7 ± 2.5 (66) | 45.8 (33) | 1.64 | 0.76–3.52 | .205 | |||

| Multigravidae | 6.1 ± 3.1 (84) | 46.3 (56) | REF | |||||

| Malaria parasite status | Positive | 6.4 ± 2.8 (83) | .028 | 41.9 (49) | .453 | 0.72 | 0.40–1.28 | .262 |

| Negative | 5.5 ± 2.8 (131) | 46.4 (77) | REF | |||||

| Anemia status | Anemic | 5.7 ± 2.9 (99) | .533 | 44.4 (63) | .915 | 0.81 | 0.46–1.42 | .462 |

| Nonanemic | 6.0 ± 2.8 (113) | 45.0 (63) | REF | |||||

| Reported fever history | Yes | 5.8 ± 2.9 (115) | .901 | 49.3 (67) | .089 | 1.61 | 0.92–2.83 | .095 |

| No | 5.9 ± 2.8 (96) | 39.2 (56) | REF | |||||

| IPTp-SP dosage | One or less | 5.7 ± 3.1 (75) | .440 | 35.1 (34) | .021 | 0.51 | 0.28–0.91 | .024 |

| Two or more | 6.0 ± 2.8 (139) | 49.5 (92) | REF | |||||

| Infant characteristics | ||||||||

| Birth weight | Low | 4.9 ± 3.0 (10) | .279 | 25.0 (2) | .473 | 0.49 | 0.08–2.98 | .439 |

| Normal | 5.9 ± 2.9 (203) | 44.7 (122) | REF | |||||

| Anemia status | Anemic | 4.2 ± 0.9 (2) | .392 | 0.0 (0) | .131 | – | – | – |

| Nonanemic | 5.9 ± 2.9 (188) | 45.2 (113) | REF | |||||

| Gender | Female | 5.9 ± 2.9 (121) | .660 | 47.6 (70) | .276 | 1.30 | 0.75–2.26 | .349 |

| Male | 5.8 ± 2.8 (93) | 41.2 (56) | REF | |||||

| Hb genotype | AS | 6.2 ± 3.2 (32) | .617 | 41.5 (17) | .437 | 0.77 | 0.36–1.23 | .490 |

| AA | 6.0 ± 2.9 (148) | 44.2 (99) | REF | |||||

| Season of birth | Rainy | 6.1 ± 2.9 (169) | .069 | 48.2 (105) | .030 | 2.82 | 1.21–6.55 | .016 |

| Dry | 5.1 ± 2.8 (38) | 31.4 (16) | REF | |||||

| Month of birth | Mar–May | 7.3 ± 2.7a (38) | .006 | 46.4 (32) | .003 | 0.57 | 0.24–1.34 | .197 |

| Jun–Aug | 5.6 ± 3.0 (94) | 56.5 (61) | 0.55 | 0.24–1.26 | .157 | |||

| Sep–Nov | 5.7 ± 2.3 (53) | 32.8 (19) | 0.31 | 0.13–0.72 | .007 | |||

| Dec–Feb | 5.1 ± 3.1 (22) | 26.5 (9) | REF | |||||

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; AFFA, age of first fever attack; Hb, hemoglobin; IPTp, intermittent presumptive treatment for malaria during pregnancy; OR, odds ratio; REF, reference group; SD, standard deviation; SP, sulfadoxine/pyrimethamine; AS, sickle cell trait; SS, sickle cell disease.

a Significantly older than the corresponding values in June–August, September–November, and December–February. The significant differences in mean AFMA between age group, gravidity, and period of birth were assessed using analyses of variance and post hoc Turkey tests, whereas the Student t test was used to compare mean AFMA with malaria parasite status, anemia status, reported fever history, IPTp-SP dosage, birth weight category, gender, Hb genotype, and season of birth. Association analysis of clinical episodes and risk factors was undertaken by logistic regression. Bold text indicate significant P values.

All 5 infants with malaria parasitemia at 3 months were born to mothers with anemia at delivery (P = .023). Nevertheless, no association was observed between maternal anemia and infant malaria parasitemia during the second, third, and fourth quarter of the year. Malaria prevalence in infants during the 1-year period was higher (P = .030) in those born during the rainy season compared with the dry season (Table 3). Note that infants born to mothers who had taken 1 or no IPTp-SP dose (adjusted OR = 0.51, 95% CI = 0.28–0.91; P = .024) in September–November (adjusted OR = 0.31, 95% CI = 0.13–0.72; P = .007) were protected from malaria during the first year of life after multivariate analysis. In contrast, infants born in the rainy season (adjusted OR = 2.82, 95% CI = 1.21–6.55; P = .016) were more susceptible to malaria (Table 3).

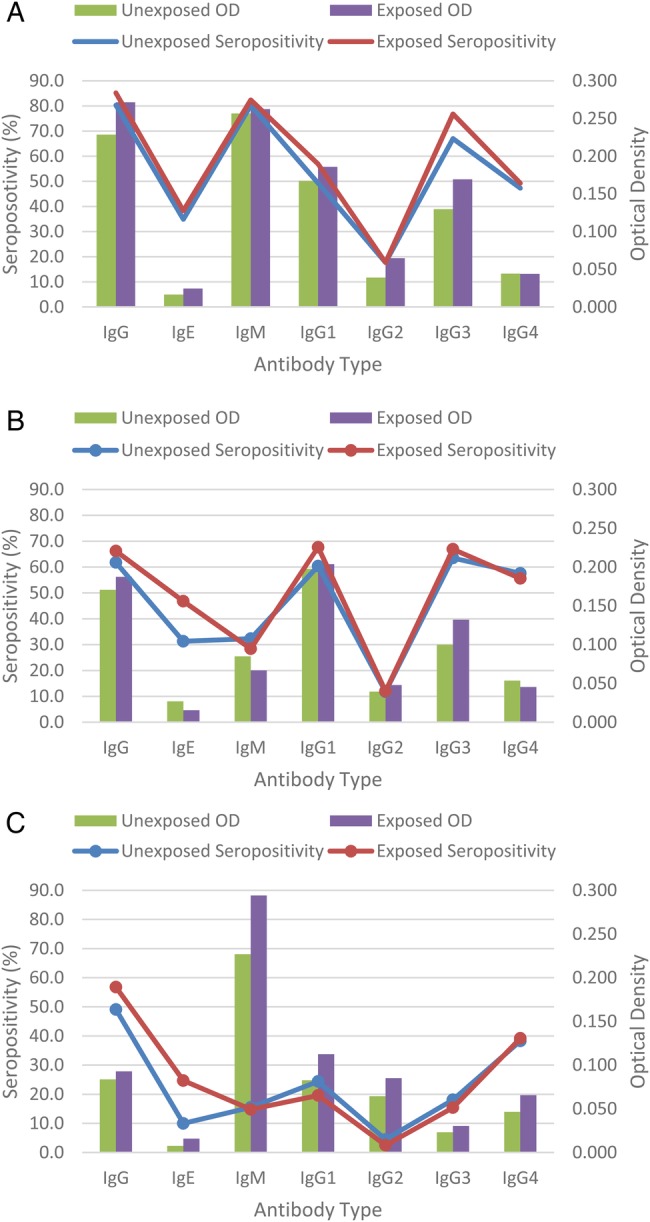

Antibody Responses

The OD and seropositivities to P falciparum-specific IgG, IgG1, IgG2, IgG3, IgG4, IgE, and IgM in malaria-exposed and malaria-unexposed pregnant women and their offspring is shown on Figure 2. Antibody levels were influenced by maternal parasitemia, maternal anemia status, IPTp dosage, and season and months of delivery (Table 4). Malaria-positive women at delivery had higher maternal IgG (P = .049) and higher maternal-cord IgG2 compared with their malaria-negative counterparts. Infants born to malaria-positive women also had higher IgE (P = .035), IgM (P = .005) and IgG2 (P = .015) compared with malaria-negative women.

Figure 2.

Plasmodium falciparum-specific immunoglobulin (Ig)G, IgG1–4, IgE, and IgM optical densities (OD) and seropositivity in malaria-exposed and unexposed pregnant women and their offspring from South Western Cameroon. A, maternal blood; B, cord blood; C, 1-year-old children.

Table 4.

Effect of Perinatal and Prenatal Risk Factors on Paired Maternal-Cord and 1-Year-Old Plasmodium falciparum-Specific IgE, IgM, IgG, IgG1, IgG2, IgG3, and IgG4 Levelsa

| Parameter | Maternal [Mean ± SD] |

Cord [Mean ± SD] |

One Year [Mean ± SD] |

||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IgG | IgE | IgM | IgG1 | IgG2 | IgG3 | IgG4 | IgG | IgE | IgM | IgG1 | IgG2 | IgG3 | IgG4 | IgG | IgE | IgM | IgG1 | IgG2 | IgG3 | IgG4 | |

| Maternal malaria parasitemia | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Positive (n = 142) | 0.271 ± 0.21 | 0.024 ± 0.08 | 0.262 ± 0.20 | 0.186 ± 0.16 | 0.065 ± 0.09 | 0.169 ± 0.20 | 0.044 ± 0.04 | 0.187 ± 0.16 | 0.015 ± 0.04 | 0.067 ± 0.14 | 0.204 ± 0.16 | 0.048 ± 0.06 | 0.132 ± 0.15 | 0.045 ± 0.03 | 0.093 ± 0.06 | 0.016 ± 0.03 | 0.294 ± 0.18 | 0.112 ± 0.14 | 0.085 ± 0.91 | 0.030 ± 0.07 | 0.066 ± 0.09 |

| Negative (n = 203) | 0.228 ± 0.18 | 0.016 ± 0.04 | 0.257 ± 0.27 | 0.167 ± 0.15 | 0.039 ± 0.06 | 0.130 ± 0.14 | 0.044 ± 0.04 | 0.171 ± 0.16 | 0.027 ± 0.08 | 0.085 ± 0.20 | 0.198 ± 0.19 | 0.039 ± 0.08 | 0.100 ± 0.11 | 0.054 ± 0.06 | 0.084 ± 0.06 | 0.008 ± 0.01 | 0.227 ± 0.15 | 0.083 ± 0.09 | 0.064 ± 0.10 | 0.023 ± 0.04 | 0.047 ± 0.06 |

| P Value | .049 | NS | NS | NS | .001 | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | .026 | NS | NS | NS | .035 | .005 | NS | .013 | NS | NS |

| Maternal anemia status | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Anemic (n = 112) | 0.247 ± 0.20 | 0.020 ± 0.07 | 0.249 ± 0.19 | 0.150 ± 0.14 | 0.048 ± 0.07 | 0.151 ± 0.17 | 0.044 ± 0.04 | 0.176 ± 0.15 | 0.021 ± 0.06 | 0.069 ± 0.15 | 0.181 ± 0.17 | 0.046 ± 0.08 | 0.113 ± 0.13 | 0.051 ± 0.05 | 0.090 ± 0.07 | 0.010 ± 0.02 | 0.266 ± 0.18 | 0.096 ± 0.12 | 0.071 ± 0.09 | 0.029 ± 0.07 | 0.057 ± 0.09 |

| Nonanemic (n = 96) | 0.246 ± 0.19 | 0.019 ± 0.05 | 0.269 ± 0.29 | 0.201 ± 0.17 | 0.051 ± 0.08 | 0.141 ± 0.17 | 0.045 ± 0.04 | 0.179 ± 0.17 | 0.023 ± 0.07 | 0.087 ± 0.21 | 0.222 ± 0.18 | 0.039 ± 0.07 | 0.114 ± 0.14 | 0.050 ± 0.05 | 0.085 ± 0.06 | 0.012 ± 0.03 | 0.244 ± 0.14 | 0.093 ± 0.11 | 0.075 ± 0.11 | 0.023 ± 0.04 | 0.051 ± 0.06 |

| P value | NS | NS | NS | .006 | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | .047 | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS |

| IPTp dosage | |||||||||||||||||||||

| ≤1 (n = 115) | 0.248 ± 0.22 | 0.018 ± 0.04 | 0.293 ± 0.32 | 0.190 ± 0.07 | 0.060 ± 0.10 | 0.151 ± 0.20 | 0.047 ± 0.04 | 0.167 ± 0.17 | 0.018 ± 0.05 | 0.076 ± 0.15 | 0.202 ± 0.17 | 0.044 ± 0.06 | 0.113 ± 0.14 | 0.044 ± 0.03 | 0.089 ± 0.06 | 0.012 ± 0.03 | 0.289 ± 0.19 | 0.105 ± 0.13 | 0.074 ± 0.10 | 0.020 ± 0.03 | 0.051 ± 0.07 |

| ≥2 (n = 158) | 0.247 ± 0.18 | 0.021 ± 0.07 | 0.236 ± 0.18 | 0.162 ± 0.14 | 0.043 ± 0.06 | 0.140 ± 0.15 | 0.042 ± 0.04 | 0.186 ± 0.05 | 0.024 ± 0.07 | 0.080 ± 0.20 | 0.194 ± 0.18 | 0.043 ± 0.08 | 0.115 ± 0.13 | 0.054 ± 0.06 | 0.087 ± 0.06 | 0.011 ± 0.02 | 0.238 ± 0.15 | 0.090 ± 0.11 | 0.073 ± 0.10 | 0.030 ± 0.07 | 0.057 ± 0.08 |

| P value | NS | NS | .061 | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | .049 | NS | NS | NS | NS |

| Season of birth | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Dry (n = 75) | 0.232 ± 0.19 | 0.039 ± 0.10 | 0.282 ± 0.19 | 0.183 ± 0.16 | 0.041 ± 0.06 | 0.188 ± 0.19 | 0.040 ± 0.04 | 0.170 ± 0.16 | 0.054 ± 0.12 | 0.074 ± 0.13 | 0.237 ± 0.20 | 0.053 ± 0.11 | 0.148 ± 0.15 | 0.045 ± 0.05 | 0.068 ± 0.07 | 0.008 ± 0.01 | 0.208 ± 0.10 | 0.096 ± 0.13 | 0.025 ± 0.02 | 0.025 ± 0.08 | 0.045 ± 0.08 |

| Rainy (n = 250) | 0.253 ± 0.20 | 0.012 ± 0.03 | 0.255 ± 0.26 | 0.166 ± 0.15 | 0.053 ± 0.08 | 0.139 ± 0.16 | 0.046 ± 0.04 | 0.189 ± 0.16 | 0.010 ± 0.02 | 0.064 ± 0.18 | 0.183 ± 0.17 | 0.041 ± 0.06 | 0.108 ± 0.13 | 0.053 ± 0.05 | 0.095 ± 0.06 | 0.012 ± 0.03 | 0.267 ± 0.18 | 0.085 ± 0.10 | 0.085 ± 0.11 | 0.026 ± 0.05 | 0.057 ± 0.07 |

| P value | NS | .001 | NS | NS | NS | .001 | NS | .028 | <.001 | NS | NS | NS | .056 | .021 | .004 | <.001 | NS | NS | <.001 | .011 | .034 |

| Month of birth | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Mar–May (n = 75) | 0.250 ± 0.21 | 0.018 ± 0.04 | 0.286 ± 0.16 | 0.150 ± 0.12 | 0.054 ± 0.07 | 0.133 ± 0.14 | 0.047 ± 0.04 | 0.186 ± 0.15 | 0.014 ± 0.01 | 0.037 ± 0.08 | 0.190 ± 0.15 | 0.045 ± 0.05Ω | 0.106 ± 0.10 | 0.056 ± 0.06 | 0.130 ± 0.06b | 0.032 ± 0.03c | 0.405 ± 0.19e | 0.114 ± 0.15 | 0.161 ± 0.13f | 0.029 ± 0.04h | 0.103 ± 0.09j |

| Jun–Aug (n = 116) | 0.260 ± 0.19 | 0.004 ± 0.02 | 0.247 ± 0.25¥ | 0.199 ± 0.17 | 0.059 ± 0.09 | 0.159 ± 0.19 | 0.054 ± 0.05 | 0.197 ± 0.15 | 0.007 ± 0.02π | 0.106 ± 0.27 | 0.197 ± 0.16 | 0.036 ± 0.05 | 0.116 ± 0.16 | 0.058 ± 0.06 | 0.086 ± 0.06a | 0.0001 ± 0.01 | 0.195 ± 0.12 | 0.075 ± 0.07 | 0.050 ± 0.07g | 0.032 ± 0.06i | 0.035 ± 0.05 |

| Sep–Nov (n = 82) | 0.228 ± 0.21 | 0.017 ± 0.03 | 0.252 ± 0.31 | 0.155 ± 0.14 | 0.038 ± 0.06$ | 0.127 ± 0.13 | 0.029 ± 0.03& | 0.174 ± 0.18 | 0.030 ± 0.09 | 0.027 ± 0.04 | 0.207 ± 0.20 | 0.053 ± 0.12 | 0.102 ± 0.11 | 0.043 ± 0.04 | 0.060 ± 0.05 | 0.004 ± 0.01d | 0.191 ± 0.10 | 0.060 ± 0.05 | 0.031 ± 0.06 | 0.015 ± 0.03 | 0.035 ± 0.05 |

| Dec–Feb (n = 52) | 0.248 ± 0.20 | 0.047 ± 0.12 | 0.309 ± 0.21 | 0.151 ± 0.13 | 0.046 ± 0.06 | 0.196 ± 0.21 | 0.043 ± 0.03 | 0.173 ± 0.17≠ | 0.047 ± 0.10 | 0.148 ± 0.15 | 0.191 ± 0.18 | 0.044 ± 0.05 | 0.161 ± 0.17 | 0.043 ± 0.02 | 0.062 ± 0.07 | 0.008 ± 0.01 | 0.216 ± 0.10 | 0.119 ± 0.15 | 0.025 ± 0.02 | 0.026 ± 0.09 | 0.052 ± 0.10 |

| P value | NS | NS | .020 | .046 | .019 | NS | <.001 | .025 | .020 | NS | NS | .001 | NS | NS | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | NS | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 |

Significantly higher than the corresponding values for Dec–Feb (P = 0.029) and Sep–Nov (P = 0.008).

Abbreviations: ANOVA, analysis of variance; Ig, immunoglobulin; IPTp, intermittent presumptive treatment for malaria during pregnancy; NS, not significant; OD, optical density; SD, standard deviation; SP, sulfadoxine/pyrimethamine.

a Boldface indicates significant results. The significance of differences in mean OD with maternal malaria parasite status, anemia status, IPTp-SP dosage groups, and season were explored using the Student t test, whereas mean OD between months of delivery were compared using ANOVA. Bold text indicate significant P values.

b Significantly higher than the corresponding values for Dec–Feb (P < .001) and Sep–Nov (P < .001).

c Significantly higher than the corresponding values for Dec–Feb (P < .001), Sep–Nov (P < .001), and Jun–Aug (P = .001).

d Significantly higher than the corresponding values for Jun–Aug (P = .009).

e Significantly higher than the corresponding values for Dec–Feb (P < .001), Sep–Nov (P < .001), and Jun–Aug (P < .001).

f Significantly higher than the corresponding values for Dec–Feb (P < .001), Sep–Nov (P < .001), and Jun–Aug (P < .001).

g Significantly higher than the corresponding values for Sep–Nov (P < .001).

h Significantly higher than the corresponding values for Dec–Feb (P = .003) and Sep–Nov (P = .001).

i Significantly higher than the corresponding values for Dec–Feb (P < .001) and Sep–Nov (P < .001).

j Significantly higher than the corresponding values for Dec–Feb (P = .001), Sep–Nov (P < .001), and Jun–Aug (P = .002).

¥ Significantly lower (P = .029) than the corresponding values for Mar–May.

$ Significantly lower (P = .011) than the corresponding values for Mar–May.

& Significantly lower than the corresponding values for Dec–Feb (P = .001), Mar–May (P < .001), and Jun–Aug (P < .001).

≠ Significantly lower than the corresponding values for Mar–May (P = .040) and Jun–Aug (P = .040).

π Significantly lower than the corresponding values for Dec–Feb (P = .013).

Ω Significantly higher than the corresponding values for Sep–Nov (P = .006) and Jun–Aug (P = .003).

Anemic women had lower peripheral (P = .006) and cord (P = .047) blood IgG1 levels (Table 4). In addition, women who had taken the recommended 2 or more IPTp-SP doses (P = .061) and their corresponding 1 year olds (P = .049) had lower IgM compared with those who had taken 1 or no IPT dose.

The rainy season was associated with lower (P < .001 each) maternal-cord and the corresponding 1-year-old infant IgE levels (Table 4). Likewise, maternal (P = .001) and cord (P = .056) blood IgG3 levels were lower in the rainy season compared with the dry season. Furthermore, maternal IgG4 (P < .001) as well as 1-year-old infant IgG (P = .008), IgG2 (P < .001), and IgG3 (P < .001) levels were lower in the rainy season months of September–November compared with June–August. However, cord IgG (P = .028) and IgG4 (P = .021) as well as 1-year-old infant IgG (P = .004), IgG2 (P < .001), IgG3 (P = .011), and IgG4 (P = .034) levels were higher in the rainy compared with the dry season. In addition, 1-year-old infants had higher IgE levels (P = .009) in the rainy season months of September–November compared with June–August.

It is interesting to note that infants who did not experience any malaria episode in the first year of life were born to mothers with lower P falciparum IgG (P = .022), IgM (P = .027), and IgG2 (P = .005) levels (Table 5). Nevertheless, no maternal antibody was predictive of infant susceptibility to malaria in the first year of life after adjusting for maternal age, gravidity, IPTp-SP dosage, malaria parasitemia, anemia, and season of delivery.

Table 5.

Effect of Maternal Antibodies on Infant Susceptibility to Malaria in the First Year of Lifea

| Antibody Type | Optical Density [Mean ± SD] |

Unadjusted P Value |

Multivariate Analysis |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Nonsusceptible | n | Susceptible | OR | 95% CI | Adjusted P Value | ||

| IgG | 139 | 0.225 ± 0.193 | 103 | 0.286 ± 0.210 | .022 | 107.08 | 0.23–498.65 | .136 |

| IgE | 84 | 0.017 ± 0.050 | 66 | 0.026 ± 0.090 | .212 | 2.712 | 0.15–47.75 | .495 |

| IgM | 116 | 0.218 ± 0.173 | 76 | 0.299 ± 0.255 | .027 | 153.20 | 0.27–866.48 | .120 |

| IgG1 | 91 | 0.172 ± 0.167 | 53 | 0.180 ± 0.145 | .335 | 0.075 | 0.00–17.16 | .350 |

| IgG2 | 139 | 0.039 ± 0.055 | 103 | 0.060 ± 0.076 | .005 | 0.407 | 0.012–9.82 | .580 |

| IgG3 | 139 | 0.115 ± 0.156 | 103 | 0.171 ± 0.181 | .081 | 0.10 | 0.01–1.97 | .130 |

| IgG4 | 139 | 0.046 ± 0.043 | 103 | 0.049 ± 0.047 | .719 | 7.892 | 0.16–397.13 | .301 |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; Ig, immunoglobulin; OR, odds ratio; SD, standard deviation.

a The significance of differences in mean antibody levels between susceptible and nonsusceptible infants was assessed using the Student t test. Multivariate analysis was undertaken using logistic regression, with the following covariates: maternal age, gravidity, IPTp-SP dosage, maternal malaria parasite status, maternal anemia status, and season of delivery. Bold text indicate significant P values.

DISCUSSION

Although in utero exposure to P falciparum has been demonstrated in South Western Cameroon [17, 21], altered susceptibility of infants to P falciparum infection has not been reported. This study assessed the effect of perinatal and prenatal risk factors on malaria in 283 infants from birth to 12 months of age. The maternal malaria parasitemia recorded at parturition in this study was still as high as previously reported in the area [17] despite the implementation of malaria-control strategies (free insecticide-treated bednets, IPTp-SP, and constant health education). This high prevalence parallels the intense perennial transmission of Plasmodium spp [20] and suggests that intense monitoring and evaluation is needed to ensure effective utilization of the control tools in place.

As previously reported elsewhere in the country [4], there was no significant relationship between either PM or gravidity and malaria prevalence in infancy in this study. Nevertheless, infants born to PM-negative mothers tended to be more sick and experienced their first malaria episode at a significantly younger age compared with their PM-positive counterparts. This finding is in contrast to the documented increased susceptibility to malaria [7–10] and nonmalarial fever episodes [11] in infants born to mothers with P falciparum infection detected at delivery. Although it is possible that the malaria parasitemia prevalence in the infants was underestimated because molecular diagnosis was not used [27], these findings suggest that exposure to P falciparum in utero may alter fetal and neonatal immune development. Parasite antigens may prime the immune system [12, 13], resulting in improved resistance to malaria in infancy.

The recent implementation of IPTp in the study area has undoubtedly improved antimalarial protection, clearing most placentas of parasites [28, 29]. However, the fact that infants born to mothers on the recommended 2 or more doses of IPTp were more vulnerable to clinical episodes is worrisome. Nevertheless, the lower IgM levels in these mothers and their 1-year-old infants suggest that the reduced protection of these infants to malaria may be linked to the reduced maternal exposure to the parasite. It is possible that IPTp might affect infant immune response (reducing their antibodies) by hindering transplacental passage of maternal antibodies [19] or fetal in utero exposure to malaria antigens [30, 31].

Consistent with previous reports [6, 32], infants under 5 months were protected from infection in this study. This protection is related to the nonexposure of the neonate to the malaria vector (free insecticide-treated nets usage and cultural factors such as swaddling), innate mechanisms that limit parasite growth (fetal Hb and para-aminobenzoic acid-deficient breast milk) [33], transplacental transfer of the mother's protective antibody [34, 35], and neonatal immune priming by transplacental transfer of parasites or their products [13].

Maternal antibodies persist in the child's blood for a few months, but this does not seem to be related to the increased resistance to malaria of infants born to placenta-infected mothers [35]. Indeed, the umbilical cord blood levels of anti-PfIgG, IgM, IgE, IgG1, IgG3, and IgG4 antibodies were similar in both groups of infants. Furthermore, the susceptibility of infants to malaria within the first year was independent of maternal antibody levels because OD were similar in both susceptible and nonsusceptible infants as reported previously [32]. This lack of association between antibodies malaria in infants suggests that other immune mechanisms might be involved in protection of infants against malaria.

The seasonal variation of malaria prevalence is well established with highest prevalence during the rainy season in the South Western region [22, 32]. Consequently, maternal and infant malaria morbidity was higher in the rainy season compared with the dry season as reported previously [8]. Because the area is flat (and warm), there are more standing water and breeding sites for, and faster breeding by, A gambiae sensu stricto and thus larger vector populations during this season. In June–August, when repeated infective bites are highest [20], the highest levels of infant morbidity, peripheral maternal parasitemia prevalence, placental infection, and the lowest age of first malaria episode were recorded. This accrues to the increased chance of both mother and child succumbing to clinical manifestation of the disease during this period.

In general, maternal seropositivity to all antimalarial antibodies except IgE and IgG2 was quite high. The raised antibody levels in pregnant women reflect maternal infection and, thus, an increased risk of fetal exposure to P falciparum antigens [4, 8]. In this study, the presence of IgM in cord (an indicator of in utero exposure) was not associated with an increased risk of infant malaria. The observed positive association between maternal antibody levels and the risk of infant infection might reflect similar risk of exposure to the parasites in mothers and infants living in the same household [36].

The seasonal variation in malaria prevalence has consequences for both the maternal-cord and infant humoral immunity, suggesting that IgM, IgE, IgG, IgG1, IgG2, IgG3, and IgG4 may be involved in the control of malaria infection. The low IgG3 in the rainy season is consistent with several studies [37–40] implicating cytophilic antibodies in protection against malaria. These antibodies mediate the opsonization of infected erythrocytes [41]. Immunoglobulin G2 has also been shown to mediate protection against malaria infection, possibly as a cytophilic antibody [42], and, as such, its low seropositivity in the rainy season reflects diminished protection against infection. Immunoglobulin E is thought to play a role in protection against malaria [43, 44], and thus the higher levels in the dry season may contribute to its lower malaria prevalence. In fact, previous studies in the region [22] have shown that children at low altitude, where malaria transmission is most intense, were more likely to be seropositive for anti-P falciparum IgE than those at high altitude and that those with high-grade parasitemia had lower levels of such parasite-specific IgE than the other parasitemics, indicating a protective role for such antibodies. Alternatively, the raised cord IgG4 levels in the rainy season may be contributing to malaria susceptibility as previously reported [42, 45]. Immunoglobulin G4 inhibits the protection provided by IgG2 [45] and the action of cytophilic antibodies in vitro [41]. Immunoglobulin G4 may thus neutralize the cellular cytotoxicity mediated by monocytes or other effector cells that depend on IgG2.

In the present study, antibody seropositivity was common at 1 year in all seasons and months of delivery. This result suggests a gradual acquisition of immunity with exposure.

CONCLUSIONS

Intermittent preventive treatment during pregnancy and month of birth have important implications for infant susceptibility to malaria. The lower IgM levels in mothers who had taken the recommended 2 or more IPTp-SP doses and their 1-year-old infants suggests that the reduced protection of these infants to malaria may be linked to the reduced maternal exposure to the parasite.

Acknowledgments

We thank the participants from the communities who made this study possible and the healthcare workers who assisted with this work.

Financial support. This work was supported by the European Community′s Seventh Framework Programme (FP7/2007-2013) under grant agreement No. 242095-European Virtual Institute for Malaria Research and the European and Developing Countries Clinical Trials Partnership-funded Central Africa Network on Tuberculosis, HIV/AIDS and Malaria.

Potential conflicts of interest. All authors: No reported conflicts.

All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest.

References

- 1.World Health Organization. World Malaria Report 2013. Available at http://www.who.int/malaria/publications/world_malaria_report_2013/report/en . Accessed 16 January 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Meeusen EN, Bischof RJ, Lee CS. Comparative T-cell responses during pregnancy in large animals and humans. Am J Rep Immunol. 2001;46:169–79. doi: 10.1111/j.8755-8920.2001.460208.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Desai M, ter Kuile FO, Nosten F, et al. Epidemiology and burden of malaria in pregnancy. Lancet Infect Dis. 2007;7:93–104. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(07)70021-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Le Hesran JY, Cot M, Personne P, et al. Maternal placental infection with Plasmodium falciparum and malaria morbidity during the first 2 years of life. Am J Epidemiol. 1997;146:826–31. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Steketee RW, Nahlen BL, Parise ME, et al. The burden of malaria in pregnancy in malaria-endemic areas. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2001;64:28–35. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2001.64.28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wagner G, Koram K, McGuinness D, et al. High incidence of asymptomatic malaria infections in a birth cohort of children less than one year of age in Ghana, detected by multicopy gene polymerase chain reaction. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1998;59:115–23. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1998.59.115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mutabingwa TK, Bolla MC, Li JL, et al. Maternal malaria and gravidity interact to modify infant susceptibility to malaria. PLoS Med. 2005;2:e407. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0020407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schwarz NG, Adegnika AA, Breitling LP, et al. Placental malaria increases malaria risk in the first 30 months of life. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;47:1017–25. doi: 10.1086/591968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bardaji A, Sigauque B, Sanz S, et al. Impact of malaria at the end of pregnancy on infant mortality and morbidity. J Infect Dis. 2011;203:691–9. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiq049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Le Port A, Watier L, Cottrell G, et al. Infections in infants during the first 12 months of life: role of placental malaria and environmental factors. PLoS One. 2011;6:e27516. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0027516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rachas A, Le Port A, Cottrell G, et al. Placental malaria is associated with increased risk of nonmalaria infection during the first 18 months of life in a Beninese population. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;55:672–8. doi: 10.1093/cid/cis490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Demeure CE, Wu CY, Shu U, et al. In vitro maturation of human neonatal CD4 T lymphocytes II. Cytokines present at priming modulate the development of lymphokine production. J Immunol. 1994;152:4775–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Malhotra I, Mungai P, Muchiri E, et al. Distinct Th1- and Th2-Type prenatal cytokine responses to Plasmodium falciparum erythrocyte invasion ligands. Infect Immun. 2005;73:3462–70. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.6.3462-3470.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.World Health Organization. A strategic framework for malaria prevention and control during pregnancy in the African region. . World Health Organization; 2004. AFR/MAL. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shulman CE, Dorman EK, Cutts F, et al. Intermittent sulphadoxine pyrimethamine to prevent severe anaemia secondary to malaria in pregnancy: a randomised placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 1999;353:632–6. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(98)07318-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rogerson SJ, Chaluluka E, Kanjala M, et al. Intermittent sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine in pregnancy: effectiveness against malaria morbidity in Blantyre, Malawi, in 1997–99. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2000;94:549–53. doi: 10.1016/s0035-9203(00)90083-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Anchang-Kimbi JK, Achidi EA, Nkegoum B, et al. Diagnostic comparison of malaria infection in peripheral blood, placental blood and placental biopsies in Cameroonian parturient women. Malar J. 2009;8:126. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-8-126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hogh B, Thompson R, Lobo V, et al. The influence of Maloprim chemoprophylaxis on cellular and humoral immune responses to Plasmodium falciparum asexual blood stage antigens in schoolchildren living in a malaria endemic area of Mozambique. Acta Trop. 1994;57:265–77. doi: 10.1016/0001-706x(94)90072-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Staalsoe T, Shulman CE, Dorman EK, et al. Intermittent preventive sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine treatment of primigravidae reduces levels of plasma immunoglobulin G, which protects against pregnancy-associated Plasmodium falciparum malaria. Infect Immun. 2004;72:5027–30. doi: 10.1128/IAI.72.9.5027-5030.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wanji S, Tanke T, Atanga SN, et al. Anopheles species of the Mount Cameroon Region; biting habits, feeding behaviour and entomological Inoculation rates. Trop Med Int Health. 2003;8:643–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3156.2003.01070.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Achidi EA, Anchang JK, Minang TJ, et al. The effect of maternal, umbilical cord and placental malaria parasitaemia on birth weight of newborn. Acta Paediatr. 2005;94:1–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2005.tb02011.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Achidi EA, Apinjoh TO, Mbunwe E, et al. Febrile status, malaria parasitaemia and gastrointestinal helminthiasis in school children resident at different altitudes. Ann Trop Med Parasitol. 2008;102:103–18. doi: 10.1179/136485908X252287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.World Health Organization. Management of severe malaria: a practical handbook. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ismail MR, Ordi J, Menendez C, et al. Placental pathology in malaria: a histological, immunohistochemical, and quantitative study. Hum Pathol. 2000;31:85–93. doi: 10.1016/s0046-8177(00)80203-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Perlmann H, Perlmann P, Berzins K, et al. Dissection of the human antibody response to the malaria antigen Pf155/RESA in to epitope specific components. Immunol Rev. 1989;112:115–31. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065x.1989.tb00555.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Perlmann H, Helmby H, Hagstedt M, et al. IgE elevation and IgE anti-malarial antibodies in P falciparum malaria: association of high IgE levels with cerebral malaria. Clin Exp Immunol. 1994;97:284–92. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.1994.tb06082.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tobian AAR, Mehlotra RK, Malhotra I, et al. Frequent umbilical cord-blood and maternal-blood infections with Plasmodium falciparum, P. malariae and P. ovale in Kenya. J Infect Dis. 2000;182:558–63. doi: 10.1086/315729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Borgella S, Fievet N, Huynh B, et al. Impact of pregnancy-associated malaria on infant malaria infection in Southern Benin. PLoS One. 2013;8:e80624. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0080624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Anchang-Kimbi JK, Achidi EA, Apinjoh TO, et al. Antenatal care visit attendance, intermittent preventive treatment during pregnancy (IPTp) and malaria parasitaemia at delivery. Malar J. 2014;13:162. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-13-162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rasheed FN, Bulmer JN, De Francisco A, et al. Relationships between maternal malaria and malarial immune responses in mothers and neonates. Parasite Immunol. 1995;17:1–10. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3024.1995.tb00960.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Xi G, Leke RG, Thuita LW, et al. Congenital exposure to Plasmodium falciparum antigens: prevalence and antigenic specificity of in utero produced antimalarial immunoglobulin M antibodies. Infect Immun. 2003;71:1242–6. doi: 10.1128/IAI.71.3.1242-1246.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Riley EM, Wagner GE, Akanmori BD, et al. Do maternally acquired antibodies protect infants from malaria infection? Parasite Immunol. 2001;23:51–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3024.2001.00364.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pasvol G, Wilson RJ. The interaction of malaria parasites with red blood cells. Br Med Bull. 1982;38:133–40. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.bmb.a071749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Redd SC, Wirima JJ, Steketee RW. Risk factors for anemia in young children in rural Malawi. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1994;51:170–4. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1994.51.170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Branch O, Udhayakumar V, Hightower A, et al. A longitudinal investigation of IgG and IgM antibody responses to the merozoite surface protein-119-kilo Dalton domain of Plasmodium falciparum in pregnant women and infants: associations with febrile illness, parasitemia, and anemia. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1998;58:211–9. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1998.58.211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Serra-Casas E, Menendez C, Bardajı A, et al. The effect of intermittent preventive treatment during pregnancy on malarial antibodies depends on HIV status and is not associated with poor delivery outcomes. J Infect Dis. 2010;201:123–31. doi: 10.1086/648595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dubois B, Deleron P, Astagneau P, et al. Isotypic analysis of Plasmodium falciparum-specific antibodies and their relation to protection in Madagascar. Infect Immun. 1993;61:4498–500. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.10.4498-4500.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rzepczyk CM, Hale K, Woodroffe N, et al. Humoral immune responses of Solomon Islanders to the merozoite surface antigen 2 of Plasmodium falciparum show pronounced skewing towards antibodies of the immunoglobulin G3 subclass. Infect Immun. 1997;65:1098–100. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.3.1098-1100.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Taylor RR, Allen SJ, Grenwood BM, et al. IgG3 antibodies to Plasmodium falciparum merozoite surface protein 2 (MSP2): increasing prevalence with age and association with clinical immunity to malaria. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1998;58:406–13. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1998.58.406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tangteerawatana P, Krudsood S, Chalermrut K, et al. Natural human IgG subclass antibodies to Plasmodium falciparum blood stage antigens and their relation to malaria resistance in an endemic area of Thailand Southeast. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 2001;32:247–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Groux H, Gysin J. Opsonization as an effector mechanism in human protection against asexual blood stages of Plasmodium falciparum: functional role of IgG subclasses. Res Immunol. 1990;141:529–42. doi: 10.1016/0923-2494(90)90021-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Leoratti FM, Durlacher RR, Lacerda MV, et al. Pattern of humoral immune response to Plasmodium falciparum blood stages in individuals presenting different clinical expressions of malaria. Malar J. 2008;7:186. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-7-186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bereczky S, Montgomery SM, Troye-Blomberg M, et al. Elevated anti-malarial IgE in asymptomatic individuals is associated with reduced risk for subsequent clinical malaria. Int J Parasitol. 2004;34:935–42. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpara.2004.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Farouk SE, Dolo A, Bereczky S, et al. Different antibody- and cytokine-mediated responses to P. falciparum parasite in two sympatric ethnic tribes living in Mali. Microbes Infect. 2005;7:110–17. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2004.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Aucan C, Traoré Y, Tall F, et al. High immunoglobulin G2 (IgG2) and low G4 (IgG4) levels are associated with human resistance to Plasmodium falciparum malaria. Infect Immun. 2000;68:1252–8. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.3.1252-1258.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]