Abstract

Background

Several original studies have investigated the effect of alcohol use disorder (AUD) on suicidal thought and behavior, but there are serious discrepancies across the studies. Thus, a systematic assessment of the association between AUD and suicide is required.

Methods

We searched PubMed, Web of Science, and Scopus until February 2015. We also searched the Psycinfo web site and journals and contacted authors. We included observational (cohort, case-control, and cross-sectional) studies addressing the association between AUD and suicide. The exposure of interest was AUD. The primary outcomes were suicidal ideation, suicide attempt, and completed suicide. We assessed heterogeneity using Q-test and I2 statistic. We explored publication bias using the Egger's and Begg's tests and funnel plot. We meta-analyzed the data with the random-effects models. For each outcome we calculated the overall odds ratio (OR) or risk ratio (RR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI).

Results

We included 31 out of 8548 retrieved studies, with 420,732 participants. There was a significant association between AUD and suicidal ideation (OR=1.86; 95% CI: 1.38, 2.35), suicide attempt (OR=3.13; 95% CI: 2.45, 3.81); and completed suicide (OR=2.59; 95% CI: 1.95, 3.23 and RR=1.74; 95% CI: 1.26, 2.21). There was a significant heterogeneity among the studies, but little concern to the presence of publication bias.

Conclusions

There is sufficient evidence that AUD significantly increases the risk of suicidal ideation, suicide attempt, and completed suicide. Therefore, AUD can be considered an important predictor of suicide and a great source of premature death.

Introduction

Suicide is one of the top 20 leading causes of death in the world for all ages [1], the third leading cause of death among people aged 15–44 years, and the second leading cause of death among people aged 10–24 years [2]. These numbers underestimate the problem and do not include suicide attempts which are up to 20 times more frequent than completed suicide [2]. Furthermore, many people who have suicidal thoughts never seek services [3].

Suicide is among the greatest sources of premature death [4]. The number of people die from homicide and suicide is much more than the number of people die from the attack in a war. In fact, for every death due to war, there are three deaths due to homicide and five deaths due to suicide [5]. It is estimated that about one million people die annually from suicide, i.e., a global mortality rate of 16 per 100,000, or one death every 40 seconds [2].

There is no single cause of suicide. Suicide is complex with several psychological, social, biological, cultural, and environmental factors [2,6,7]. Alcohol and drug abuse are among the major risk factors for suicide [1,3]. The harmful use of alcohol is a global problem, which is associated with many serious individual and social consequences. In addition to the chronic diseases that may develop in those who drink large amounts of alcohol over a long period of time, a significant proportion of the disease burden is the result of intentional and unintentional injuries, such as violent behaviors, suicides, and traffic accidents [8].

Several reviews have discussed the relationship between alcohol use disorder (AUD) and suicidal thoughts and behavior, but none has given a pooled effect estimate [9–11]. An old meta-analysis was conducted by Smith et al [12] based on studies published before 1999. They measured blood alcohol concentration among unintentional injury deaths as well as homicide and suicide cases and concluded that blood alcohol concentration was high among the victims. However, no pooled estimate of the association between suicide and AUD was reported. Another meta-analysis conducted by Fazel et al in 2008 [13] to estimate the alcohol-related risk of completed suicide in prisoners. The results of this meta-analysis was limited to a specific population which may not be generalized to the general population. Furthermore, the association between AUD and suicidal ideation and suicide attempt was not investigated either.

Current evidence based on epidemiological studies has shown that AUD is associated with an increased risk of suicide, but there are serious discrepancies across the studies. Therefore, a systematic assessment of the association between AUD and suicide is needed. This meta-analysis was carried out to estimate the association between AUD and suicidal ideation, suicide attempt, and completed suicide separately.

Materials and Methods

Criteria for including studies

The supporting PRISMA checklist of this review is available as supporting information; see S1 PRISMA Checklist. Cohort, case-control, and cross-sectional studies addressing the association between AUD and suicide were included irrespective of participants' age, gender, language, nationality, race, religion, or publication status (published as a full text article in a journal or presented as an abstract at a conference). The observational studies addressing suicide rate among alcohol abusers without comparison group or self-harm without suicide intention were excluded.

The exposure of interest was AUD including alcohol abuse and alcohol dependence [14]. AUD is a condition characterized by the harmful consequences of recurrent alcohol use and physiological dependence on alcohol resulting in harm to physical and mental health and impairment of social and occupational activities [15]. The studies addressing the association between AUD and suicide among drug abusers or among patients with mental disorders were excluded.

The primary outcomes were suicidal ideation, suicide attempt, and completed suicide. A suicidal ideation is "thinking about, considering, or planning for suicide" [16]. A suicide attempt is "a non-fatal self-directed potentially injurious behavior with any intent to die as a result of the behavior" [16]. A completed suicide is "a death caused by self-directed injurious behavior with any intent to die as a result of the behavior" [16]. The death due to overdose without intent to die was not included. The studies reporting suicide as a general term without distinguishing between suicidal ideation, suicide attempt, or completed suicide were excluded.

Search methods

The search strategy was as follows: (suicide or suicidal or suiciding or self-injurious behavior or self-immolation or self-destruction or self-slaughter or self-mutilation or self-harm or self-inflicted or self-injury) and (alcohol or alcoholic or alcoholism or harmful drinking or dependent drinking or over-drinking or harmful drinker or heavy drinker or hard drinker or problem drinker or pathological drinker or ethanol) and (cohort stud* or follow-up stud* or longitudinal stud* or case-control stud* or case-base stud* or cross-sectional stud* or observational stud* or survey).

The main bibliographic databases, including PubMed, Scopus, and Web of Science, were searched until February 2015. The reference lists of all included studies were scanned and the authors of the identified studies were contacted for additional eligible studies. The Psycinfo web site was searched as well.

Data collection and analysis

Two authors (ND and JP) independently screened the title and abstract of the retrieved studies and decided on which studies met the inclusion criteria of this meta-analysis. The between authors disagreements were resolved through discussion among the authors until consensus was reached, otherwise a senior author arbitrated.

An electronic data sheet was developed and used for data extraction. Two authors (ND and JP) extracted data independently. The between authors disagreements were resolved through discussion among the authors until consensus was reached, otherwise a senior author arbitrated. The following data were collected: first author’s name, year of publication, country, mean age, gender, type of population (general or conscripts/veterans), study design (cohort, case-control, cross-sectional), suicide (ideation, attempt, completed), sample size, effect estimate with associated 95% confidence interval (CI).

The quality of reporting and the risk of bias of the included studies was explored using Newcastle Ottawa Statement Manual [17]. The scale allocates a maximum of nine stars for quality of selection, comparability, exposure and outcome of the study participants. The studies with seven star-items or more were considered a low risk of bias and those with six star-items or fewer were considered a high risk of bias.

Heterogeneity was explored using Q-test [18] and its quantity was measured using the I2 statistic [19]. Publication bias was assessed using the Egger's [20] and Begg's [21] tests and visualized by the funnel plot.

Measures of alcohol effect were expressed as risk ratio (RR) and odds ratio (OR). RR is the relative incidence risk of events in the exposed group versus the non-exposed group occurring at any given point in time. OR is the relative odds of outcome in the exposed group versus the non-exposed group occurring at any given point in time. Wherever reported, we used full adjusted forms of RR and OR controlled for at least one or more potential confounding factors such as age, gender, race, mental disorder, drug abuse, smoking, marital status, body mass index, educational level, employment status, income, and living alone.

Data were analyzed and the results were reported using a random effects model [22]. In order to explore the source of heterogeneity, we performed meta-regression analysis considering mean age, gender (percent of men), adjusted/unadjusted effect estimates, and a high/low risk of bias as covariates. All statistical analyses were performed at a significance level of 0.05 using Stata software, version 11 (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA).

Results

Description of studies

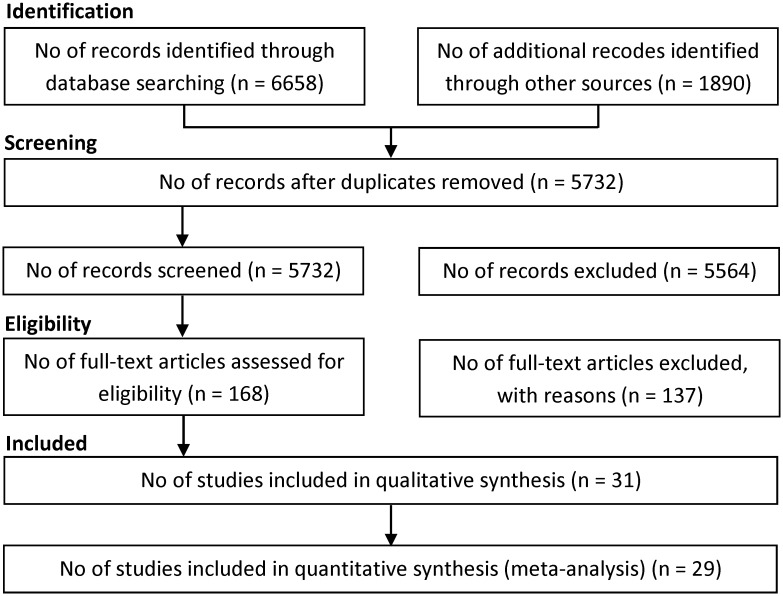

We retrieved 8548 references until February 2015, including 6658 references through searching electronic databases, 1890 references through checking other sources, including reference lists, relevant web sites, or personal contact with authors of the included studies. We excluded 8380 duplicates and clearly irrelevant references through reading titles and abstracts. Of the 168 references considered potentially eligible after screening, 137 studies were excluded because they were not original article (i.e., letter, commentary, review) or did not meet the inclusion criteria (Fig 1). Eventually, 31 studies included in the meta-analysis, including 9 cohort studies [23–31] and 10 case-control studies [32–41] and 12 cross-sectional studies [42–53]. All included studies were published in English. In cases of multiple publication, the last report was used.

Fig 1. Flow of information through the different phases of the systematic review.

The characteristics of the included studies are summarized and listed in Table 1. The included studies involved 420,732 participants. A study [52] assessed the association between AUD and suicide in two different countries (the USA and France) concurrently. Thus, this study is presented twice in Table 1 as well as the forest plots. Eight studies reported the association between AUD and suicidal ideation, 15 studies reported the association between AUD and suicide attempt, and 14 studies reported the association between AUD and completed suicide. Since four studies [29,30,46,52] have reported the association between AUD and suicidal ideation, suicide attempts, and completed suicide concurrently, therefore, the number effect sizes given in the forest plots is more than the total number of included studies. Some cohort studies reported RR and some others as well as the case-control and cross-sectional studies reported OR.

Table 1. Summary of studies results.

| Newcastle Ottawa Score | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1st author | Country | Age | Gender | Population | Study | Estimate | Sample | Sel | Com | E/O |

| Agrawal 2013 | USA | 18–27 | Female | General | Cross-sectional | Crude | 3,787 | **** | * | ** |

| Akechi 2006 | Japan | 40–69 | Male | General | Cohort | Adjusted | 43,383 | **** | ** | *** |

| Andreasson 1991 | Sweden | 18–21 | Male | General | Cohort | Adjusted | 49,464 | *** | ** | ** |

| Aseltine 2009 | USA | 11–19 | Both | General | Cross-sectional | Adjusted | 32,217 | ** | ** | ** |

| Bagge 2013 | USA | 18–64 | Both | General | Case-Control | Adjusted | 192 | **** | ** | ** |

| Beck 1989 | USA | 29.9 | Both | General | Case-Control | Adjusted | 413 | *** | ** | ** |

| Bernal 2007 | Europe | 18+ | Both | General | Cross-sectional | Adjusted | 21,425 | *** | ** | ** |

| Bunevicius 2014 | Lithuania | 18–89 | Both | General | Cross-sectional | Adjusted | 998 | *** | ** | ** |

| Coelho 2010 | Brazil | 18+ | Both | General | Cross-sectional | Adjusted | 1,464 | ** | ** | ** |

| Donald 2006 | Australia | 18–24 | Both | General | Case-Control | Adjusted | 380 | **** | ** | ** |

| Elizabeth 2009 | USA | 13–18 | Both | General | Cross-sectional | Crude | 31,953 | ** | * | * |

| Feodor 2014 | Denmark | 16+ | Both | General | Cohort | Adjusted | 32,010 | **** | ** | *** |

| Flensborg 2009 | Denmark | 20–93 | Both | General | Cohort | Adjusted | 18,146 | **** | ** | *** |

| Grossman 1991 | USA | 14.4 | Both | General | Cross-sectional | Adjusted | 6,637 | *** | ** | *** |

| Gururaj 2004 | India | 15–60 | Both | General | Case-Control | Crude | 538 | **** | * | ** |

| Kaslow 2000 | USA | 18–64 | Female | General | Case-Control | Crude | 285 | *** | * | ** |

| Kettl 1993 | Alaska | 30.8 | Both | General | Case-Control | Crude | 66 | ** | * | *** |

| Lesage 1994 | Canada | 18–35 | Male | General | Case-Control | Crude | 150 | **** | * | *** |

| Méan 2005 | Switzerland | 16–21 | Both | General | Cohort | Adjusted | 148 | *** | ** | * |

| Morin 2013 | Sweden | 70–91 | Both | General | Case-Control | Adjusted | 515 | *** | ** | ** |

| Orui 2011 | Japan | 20+ | Both | General | Cross-sectional | Adjusted | 770 | *** | ** | ** |

| Petronis 1990 | USA | Adults | Both | General | Cohort | Adjusted | 13,673 | FTU | FTU | FTU |

| Pridemore 2013 | Russia | 25–54 | Male | General | Case-Control | Adjusted | 1,640 | **** | ** | ** |

| Randall 2014 | Benin | 12–16 | Both | General | Cross-sectional | Adjusted | 2,690 | ** | ** | ** |

| Rossow 1995 | Norway | 19+ | Male | Conscripts | Cohort | Crude | 41,399 | **** | * | *** |

| Rossow 1999 | Sweden | Middle-aged | Male | General | Cohort | Adjusted | 46,490 | **** | ** | *** |

| Shoval 2014 | Israel | 21–45 | Both | General | Cross-sectional | Adjusted | 1,237 | *** | ** | ** |

| Swahn 2012 | France | 19-Nov | Both | General | Cross-sectional | Adjusted | 13,187 | ** | ** | ** |

| Swahn 2012 | USA | 19-Nov | Both | General | Cross-sectional | Adjusted | 15,136 | ** | ** | ** |

| Tidemalm 2008 | Sweden | 37.7 | Both | General | Cohort | Adjusted | 39,685 | **** | ** | *** |

| Zhang 2010 | China | 34–60 | Male | General | Cross-sectional | Adjusted | 454 | ** | ** | ** |

| Zonda 2006 | Hungary | 52.1 | Both | General | Case-Control | Crude | 200 | *** | * | ** |

Sel: Selection; Com: Comparability; E/O: Exposure/Outcome; FTU: Full text unavailable

Adjusted means controlled for one or more of the following factors: age, gender, race, mental disorder, drug abuse, smoking, marital status, body mass index, educational level, employment status, income, living alone

The results of assessing risk of bias of the included studies are given in Table 1 based on the Newcastle Ottawa Statement Manual. Based on this manual, 10 studies had a high risk of bias and 20 studies had a low risk of bias. A study [28] had no full text and thus its risk of bias was not evaluated.

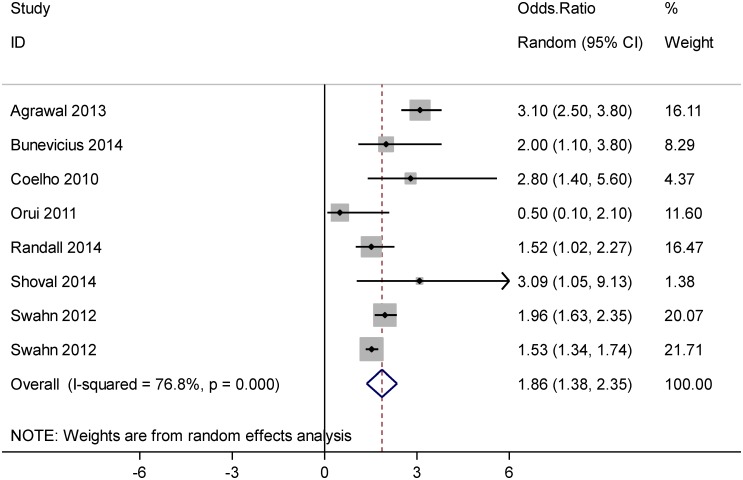

Effect of exposure

Fig 2 shows the results of the meta-analysis addressing the association between AUD and suicidal ideation. Based on this forest plot, AUD was significantly associated with suicidal ideation, OR = 1.86 (95% CI: 1.38, 2.35).

Fig 2. Forest plot of the association between alcohol use disorder and suicide ideation.

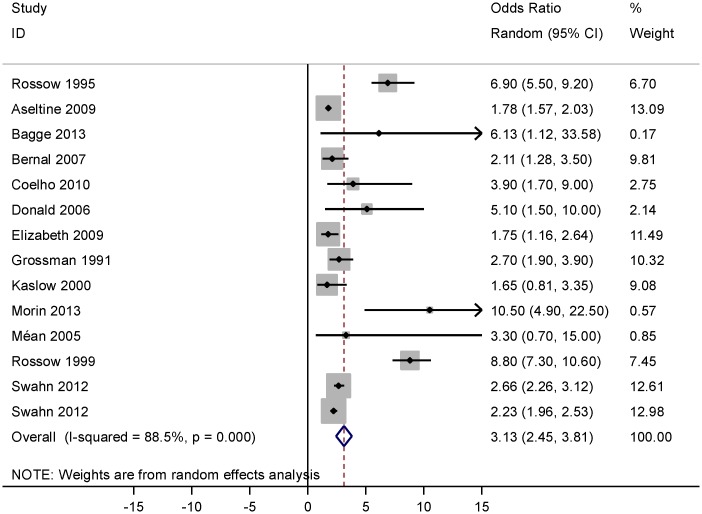

Fig 3 gives the forest plot of the association between AUD and suicide attempt. According to this forest plot, AUD was strongly associated with suicide attempt, OR = 3.13 (95% CI: 2.45, 3.81). There was an extreme value (outlier) [28] among the studies with OR = 18.0 (95% CI: 2.75, 118) that was excluded from the meta-analysis.

Fig 3. Forest plot of the association between alcohol use disorder and suicide attempt.

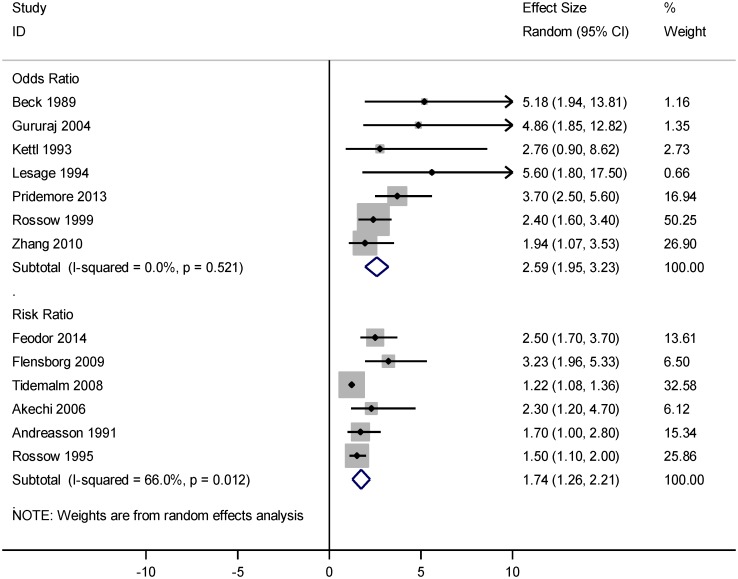

Fig 4 represents the forest plot of the association between AUD and completed suicide. Based on this forest plot, AUD was significantly associated with completed suicide, OR = 2.59 (95% CI: 1.95, 3.23) and RR = 1.74 (95% CI: 1.26, 2.21). There was an extreme value [41] with OR = 0.541 (95% CI: 0.30, 0.97) that was excluded from the meta-analysis.

Fig 4. Forest plot of the association between alcohol use disorder and completed suicide.

Heterogeneity and publication bias

Heterogeneity was explored using Q-test and the quantity of heterogeneity was measured by the I2 statistic (Figs 2–4). Fig 2. shows a substantial heterogeneity (I2 = 76.8%, P<0.001) among studies addressing the association between AUD and suicidal ideation. Fig 3. indicates a considerable heterogeneity (I2 = 88.5%, P<0.001) among studies addressing the association between AUD and suicide attempt. As shown in Fig 4, there was no evidence of heterogeneity (I2 = 0.0%, P = 0.521) across studies reporting OR estimates of AUD related completed suicide, but there was a moderate heterogeneity (I2 = 66.0%, P = 0.012) among the studies reporting RR.

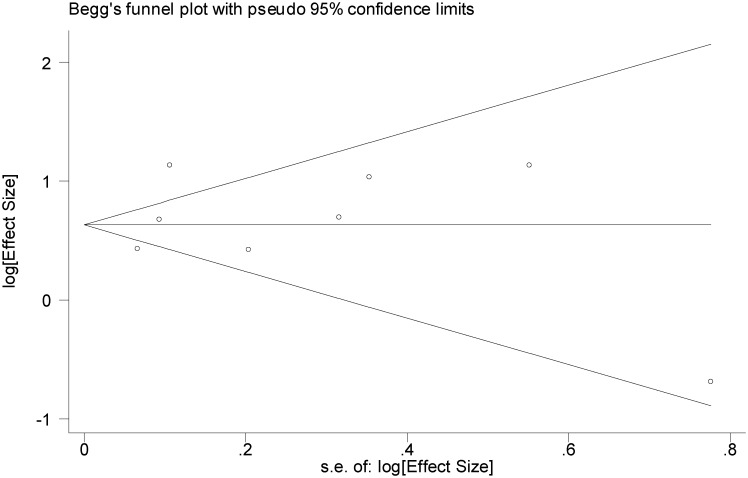

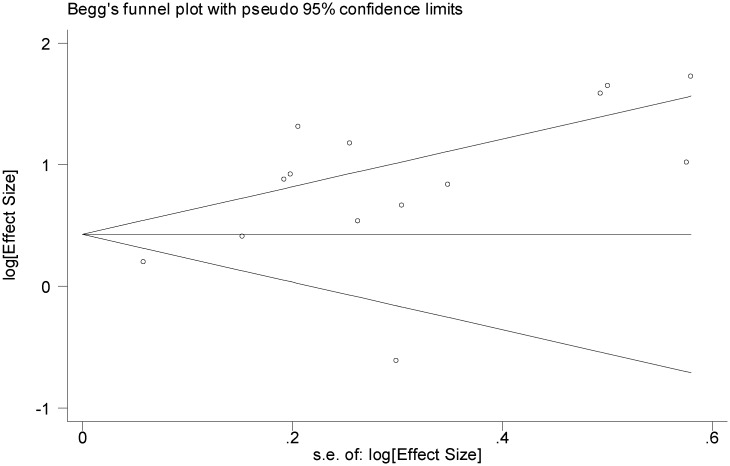

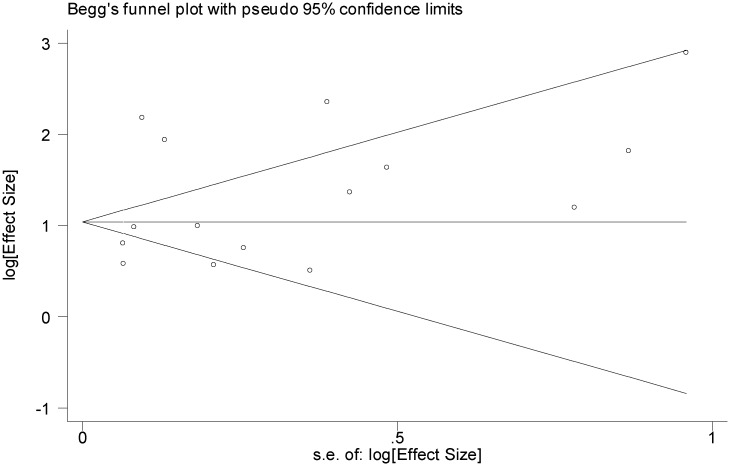

We explored the possibility of publication bias using the funnel plot (Figs 5–7) as well as the Egger's and Begg's statistical tests. Based on Figs 5 and 6, the studies are scattered nearly symmetrically on both sides of the horizontal line indicating no evidence of publication bias in the studies reflecting the association between AUD and suicidal ideation and suicide attempt. The results of Egger's and Begg's tests confirmed this issue and revealed no evidence of publication bias among the studies addressing the association between AUD and suicidal ideation (P = 0.740 and P = 0.805) and suicide attempt (P = 0.363 and P = 0.125), respectively, As shown in Fig 7, studies are scattered asymmetrically on both sides of the horizontal line reflecting evidence of publication bias among the studies addressing the association between AUD and completed suicide. The Egger's test was statistically significant (P = 0.008), but the Begg's test was not (P = 0.477).

Fig 5. Funnel plot of included studies assessing the publication bias in studies addressing the association between alcohol use disorder and suicide ideation.

Fig 7. Funnel plot of included studies assessing the publication bias in studies addressing the association between alcohol use disorder and completed suicide.

Fig 6. Funnel plot of included studies assessing the publication bias in studies addressing the association between alcohol use disorder and suicide attempt.

Moderator analysis

In order to explore the sources of heterogeneity, we performed meta-regression analysis considering mean age, gender (percent of men), adjusted/unadjusted effect estimates, and a high/low risk of bias as covariates (Table 2). Multivariate meta-regression indicates the impact of moderator variables on study effect size. According to the results of meta-regression analysis, none of the covariates had a significant effect on the observed heterogeneity. The effects of covariates in the meta-regression are presented based on a logarithmic scale, so that it is possible to estimate the risk of suicidal ideation, attempted suicide, and completed suicide based on different scenarios of moderator variables.

Table 2. Analysis of meta-regression exploring sources of heterogeneity considering mean age, sex, adjusted versus unadjusted effect estimates, and studies with a high risk of bias versus those with a low risk of bias as covariates based on logarithmic scale.

| Variables | Coefficient | SE | 95% CI | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Suicide ideation | ||||

| Mean age (yr) | -0.043 | 0.032 | -0.182, 0.096 | 0.313 |

| Gender (% of men) | 0.783 | 1.822 | -7.058, 8.625 | 0.709 |

| Adjustment (0 = unadjusted; 1 = adjusted) | -0.115 | 0.995 | -4.396, 4.165 | 0.918 |

| Risk of bias (0 = high risk; 1 = low risk) | 1.263 | 1.011 | -3.089, 5.616 | 0.338 |

| Constant | 0.804 | 0.963 | -3.341, 4.949 | 0.482 |

| Attempted suicide | ||||

| Mean age (yr) | 0.015 | 0.010 | -0.009, 0.040 | 0.195 |

| Gender (% of men) | 0.836 | 0.633 | -0.623, 2.297 | 0.223 |

| Adjustment (0 = unadjusted; 1 = adjusted) | 0.061 | 0.345 | -0.736, 0.859 | 0.863 |

| Risk of bias (0 = high risk; 1 = low risk) | 0.345 | 0.482 | -0.766, 1.457 | 0.494 |

| Constant | 0.159 | 0.469 | -0.923, 1.241 | 0.743 |

| Completed suicide | ||||

| Mean age (yr) | -0.017 | 0.017 | -0.057, 0.022 | 0.357 |

| Gender (% of men) | -0.072 | 0.857 | -2.011, 1.867 | 0.935 |

| Adjustment (0 = unadjusted; 1 = adjusted) | -0.015 | 0.394 | -0.908, 0.876 | 0.969 |

| Risk of bias (0 = high risk; 1 = low risk) | 0.591 | 0.460 | -0.450, 1.634 | 0.231 |

| Constant | 1.126 | 1.174 | -1.529, 3.782 | 0.363 |

Discussion

This meta-analysis revealed that AUD was significantly associated with an increased risk of suicidal ideation, suicide attempt, and completed suicide. Alcohol and psychiatric disorder have a complicated relationship. Alcohol drinking can have negative effects on mental health, causing psychiatric disorders and increasing the risk of suicide [54]. Countries that have higher rates of alcohol use generally also have higher rates of suicide [55]. Furthermore, current evidence indicates an association between alcohol dependence and impulsive suicide attempts [56,57]. In addition, there is a close link between alcohol abuse and depression and it is often difficult to determine which of the two is the main leading condition [58]. Pompili et al have suggested that people with alcohol disorder should be screened for suicidality as well as psychiatric disorders [59].

Smith et al [12] conducted a meta-analysis in 1999 and reported that the overall percentage of the blood alcohol concentration was significantly higher in suicide cases. However, the magnitude of the suicide risk was not evaluated. Fazel et al [13] conducted a meta-analysis to examine the risk factors associated with suicide in prisoners. They reported that risk of completed suicide increases 3-fold in prisoners with a history of alcohol use. This effect estimate is greater than our estimate. This inconsistency between the results is acceptable because, several studies have indicated that suicide rates in prisoners are 5 to 10 times higher than the general population [60,61].

As shown in Fig 4, the summary measure obtained from OR, estimating the risk of completed suicide, was greater than that obtained from RR. The reason is straightforward because OR inherently tends to exaggerate the magnitude of the association [62].

There was a significant heterogeneity between the included studies (small P value of Q-test and large I2 statistic). The results of the statistical tests assessing heterogeneity should be interpreted with caution. When the sample size is small or the number of studies is limited, the Q-test has low statistical power. On the other hand, when the sample size or the number of the included studies is large, the test has high power in detecting a small amount of heterogeneity that may be clinically unimportant [18]. Therefore, a part of observed heterogeneity can be attributed to the number of studies (31 studies) included in the meta-analysis and the large sample size (involving 420,732 participants). However, another part of observed heterogeneity can be attributed to the discrepancies across the studies. The OR estimates of suicidal ideation were reported from 0.5 to 3.10 and that of suicide attempt from 1.65 to 10.50. The source of observed heterogeneity was explored using a meta-regression analysis considering mean age, sex, adjusted/unadjusted effect estimates, and methodological quality of the included studies as covariates. However, none of these covariates had a significant effect on the observed heterogeneity. One reason that may explain this heterogeneity is that individual studies come from different settings with different populations, sample sizes and methodological quality.

There was an outlier (OR = 18.0) [28] among the included studies addressing the association between AUD and suicide attempt. This cohort study was a report of research on suicide attempt based on an analysis of data from the Epidemiologic Catchment Area surveys, enrolling 13,673 participants, in the United States, in the early 1980s. This study reported the association between active alcoholism and suicide attempt using multiple conditional logistic regression analysis. The full text of this study was not accessible for further evaluation of the study population and its associated eligibility criteria. Thus, the reason of this extreme value remained unclear.

There were some limitations in this meta-analysis as follows. First, wherever possible, we used the full adjusted forms of RR and OR controlling for factors such as age, gender, race, mental disorder, drug abuse, smoking, marital status, body mass index, educational level, employment status, income, and living alone. However, the confounding effect was not completely ruled out because some studies reported crude forms of RR or OR estimates. This issue may lead to overestimation of the overall measures of association. Second, there were 12 studies (mostly old studies) that seemed potentially eligible for inclusion in this meta-analysis, but their full texts were not accessible. We requested the relevant institutes to find the full texts for us, but they could not. We tried to contact the corresponding authors to send us the full texts, but the authors did not respond. This issue may raise the possibility of selection bias.

Despite the above limitations, the current meta-analysis could efficiently estimate the association between AUD and suicide. Furthermore, a wide search strategy was developed in order to increase the sensitivity of the search to include as many studies as possible. Our study included all types of observational studies irrespective of age, country, race, publication date, and language. We screened 8548 retrieved references and included 31 eligible studies in the meta-analysis involving 420,732 participants. Thus, the evidence was sufficient to make a robust conclusion regarding the objective of the study for estimating the association between AUD and suicide.

We can have high confidence based on the current evidence that AUD increases the risk of suicide. Therefore, further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. This finding supports the alcohol cessation programs to reduce alcohol use among the general population. However, there is insufficient evidence in regard to the dose-response relationship between alcohol drinking and risk of suicide. Further investigation based on observational studies are needed to expect the dose-response pattern of alcohol-related suicide.

Conclusion

This meta-analysis measured the association between AUD and suicide. Based on current evidence, AUD significantly increases the risk suicidal ideation, suicide attempt, and completed suicide. Therefore, AUD can be considered an important predictor of suicide and a great source of premature death.

Supporting Information

(DOC)

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the Islamic Azad University, Hamadan Branch, for financial support of this study. We also thank our colleagues Ensieh Jenabi and Mina Madadian for finding full text articles.

Data Availability

All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files.

Funding Statement

The authors would like to thank the Islamic Azad University, Hamadan Branch, for financial support of this study. The funder had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1. World Health Organization. Suicide prevention. Geneva: WHO; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 2. World Health Organization; Suicide prevention (SUPRE). Geneva: WHO; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Understanding suicide: fact sheet. Atlanta: CDC; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Poorolajal J, Esmailnasab N, Ahmadzadeh J, Azizi Motlagh T. The burden of premature mortality in Hamadan Province in 2006 and 2010 using standard expected years of potential life lost: a population-based study. Epidemiol Health. 2012;34: e2012005 10.4178/epih/e2012005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. World Health Organization. 10 facts on injuries and violence Beginning. Geneva: WHO; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Amiri B, Pourreza A, Rahimi Foroushani A, Hosseini SM, Poorolajal J. Suicide and associated risk factors in Hamadan province, west of Iran, in 2008 and 2009. J Res Health Sci. 2012;12: 88–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Poorolajal J, Rostami M, Mahjub H, Esmailnasab N. Completed suicide and associated risk factors: A six-year population based survey. Arch Iran Med. 2015;18(1): 39–43. doi: 0151801/AIM.0010 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. World Health Organization. Alcohol. Geneva: WHO; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Borges G, Loera CR. Alcohol and drug use in suicidal behaviour. Curr Opin Psychiatry 2010;23: 195–204. 10.1097/YCO.0b013e3283386322 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Cheryl J, Cherpitel CJ, Borges GLG, Wilcox HC. Acute alcohol use and suicidal behavior: A review of the literature. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 2004;28: 18S–28S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Wilcox HC, Conner KR, Caine ED. Association of alcohol and drug use disorders and completed suicide: an empirical review of cohort studies. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2004;76: S11–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Smith GS, Branas CC, Miller TR. Fatal nontraffic injuries involving alcohol: A metaanalysis. Ann Emerg Med. 1999;33: 659–668. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Fazel S, Cartwright J, Norman-Nott A, Hawton K. Suicide in prisoners: a systematic review of risk factors. J Clin Psychiatry. 2008;69: 1721–1731. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. National Institutes of Health. Alcohol Use Disorder: A Comparison Between DSM—IV and DSM–5. NIH; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 15. National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. Alcohol use disorder: a comparison between DSM—IV and DSM–5: NIH Publication; No. 13–7999; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Definitions: self-directed Violence. Atlanta: CDC; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Wells GA, Shea B, O'Connell D, Peterson J, Welch V, Losos M, et al. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomised studies in meta-analyses. Ontario: Ottawa Hospital Research Institute; 2009. 10.1371/journal.pntd.0002195 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Higgins JPT, Green S. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions Version 5.0.1 [updated September 2008]. The Cochrane Collaboration; 2008. Available from www.cochrane-handbook.org 10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181b1c99f [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Higgins JPT, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman D Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ. 2003;327: 557–560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Egger M, Davey SG, Schneider M, Minder C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ. 1997;315: 629–634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Begg CB, Mazumdar M. Operating characteristics of a rank correlation test for publication bias. Biometrics. 1994;50: 1088–1101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials. 1986;7: 177–188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Akechi T, Iwasaki M, Uchitomi Y, Tsugane S Alcohol consumption and suicide among middle-aged men in Japan. Br J Psychiatry. 2006;188: 231–236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Andreasson S, Romelsjo A, Allebeck P. Alcohol, social factors and mortality among young men. Br J Addict. 1991;86: 877–887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Feodor Nilsson S, Hjorthøj CR, Erlangsen A, Nordentoft M. Suicide and unintentional injury mortality among homeless people: a Danish nationwide register-based cohort study. Eur J Public Health. 2014;24: 50–56. 10.1093/eurpub/ckt025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Flensborg-Madsen T, Knop J, Mortensen EL, Becker U, Sher L, Grønbaek M. Alcohol use disorders increase the risk of completed suicide—Irrespective of other psychiatric disorders. A longitudinal cohort study. Psychiatry Res. 2009;167: 123–130. 10.1016/j.psychres.2008.01.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Méan M, Righini NC, Narring F, Jeannin A, Michaud PA. Substance use and suicidal conduct: A study of adolescents hospitalized for suicide attempt and ideation. Acta Paediatr. 2005;94: 952–959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Petronis KR, Samuels JF, Moscicki EK, Anthony JC. An epidemiologic investigation of potential risk factors for suicide attempts. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 1990;25: 193–199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Rossow I, Amundsen A. Alcohol abuse and suicide: a 40-year prospective study of Norwegian conscripts. Addiction. 1995;90: 685–691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Rossow I, Romelsjo A, Leifman H. Alcohol abuse and suicidal behaviour in young and middle aged men: differentiating between attempted and completed suicide. Addiction. 1999;94: 1199–1207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Tidemalm D, Langstrom N, Lichtenstein P, Runeson B. Risk of suicide after suicide attempt according to coexisting psychiatric disorder: Swedish cohort study with long term follow-up. BMJ. 2008;337: a2205 10.1136/bmj.a2205 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Bagge CL, Lee HJ, Schumacher JA, Gratz KL, Krull JL, Holloman G Jr. Alcohol as an acute risk factor for recent suicide attempts: a case-crossover analysis. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2013;74: 552–558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Beck AT, Steer RA. Clinical predictors of eventual suicide: a 5- to 10-year prospective study of suicide attempters. J Affect Disord. 1989;17: 203–209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Donald M, Dower J, Correa-Velez I, Jones M. Risk and protective factors for medically serious suicide attempts: a comparison of hospital-based with population-based samples of young adults. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2006;40: 87–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Gururaj G, Isaac MK, Subbakrishna DK, Ranjani R. Risk factors for completed suicides: a case-control study from Bangalore, India. Inj Control Saf Promot. 2004;11: 183–191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Kaslow N, Thompson M, Meadows L, Chance S, Puett R, Hollins L, et al. Risk factors for suicide attempts among African American women. Depress Anxiety. 2000;12: 13–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Kettl P, Bixler EO. Alcohol and suicide in Alaska Natives. Am Indian Alsk Native Ment Health Res. 1993;5: 34–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Lesage AD, Boyer R, Grunberg F, Vanier C, Morissette R, Ménard-Buteau C, et al. Suicide and mental disorders: A case-control study of young men. Am J Psychiatry. 1994;151: 1063–1068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Morin J, Wiktorsson S, Marlow T, Olesen PJ, Skoog I, Waern M. Alcohol Use Disorder in Elderly Suicide Attempters: A Comparison Study. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2013;21: 196–203. 10.1016/j.jagp.2012.10.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Pridemore WA. The impact of hazardous drinking on suicide among working-age Russian males: an individual-level analysis. Addiction. 2013;108: 1933–1941. 10.1111/add.12294 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Zonda T. One-hundred cases of suicide in Budapest: a case-controlled psychological autopsy study. Crisis. 2006;27: 125–129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Agrawal A, Constantino AM, Bucholz KK, Glowinski A, Madden PA, Heath AC, et al. Characterizing alcohol use disorders and suicidal ideation in young women. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2013;74: 406–412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Aseltine RH Jr., Schilling EA, James A, Glanovsky JL, Jacobs D. Age variability in the association between heavy episodic drinking and adolescent suicide attempts: findings from a large-scale, school-based screening program. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2009;48: 262–270. 10.1097/CHI.0b013e318195bce8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Bernal M, Haro JM, Bernert S, Brugha T, de Graaf R, Bruffaerts R, et al. Risk factors for suicidality in Europe: results from the ESEMED study. J Affect Disord. 2007;101: 27–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Bunevicius R, Liaugaudaite V, Peceliuniene J, Raskauskiene N, Bunevicius A, Mickuviene N. Factors affecting the presence of depression, anxiety disorders, and suicidal ideation in patients attending primary health care service in Lithuania. Scand J Prim Health Care. 2014;32: 24–29. 10.3109/02813432.2013.873604 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Coelho BM, Andrade LH, Guarniero FB, Wang YP. The influence of the comorbidity between depression and alcohol use disorder on suicidal behaviors in the Sao Paulo Epidemiologic Catchment Area Study, Brazil. Rev Bras Psiquiatr. 2010;32: 396–408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Elizabeth AS, Robert H. Aseltine Jr, Glanovsky JL, Jamesa A, Jacobs D. Adolescent alcohol use, suicidal ideation, and suicide attempts. J Adolesc Health. 2009;44: 335–341. 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2008.08.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Grossman DC, Milligan BC, Deyo RA. Risk factors for suicide attempts among Navajo adolescents. Am J Public Health. 1991;81: 870–874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Orui M, Kawakami N, Iwata N, Takeshima T, Fukao A. Lifetime prevalence of mental disorders and its relationship to suicidal ideation in a Japanese rural community with high suicide and alcohol consumption rates. Environ Health Prev Med. 2011;16: 384–389. 10.1007/s12199-011-0209-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Randall JR, Doku D, Wilson ML, Peltzer K. Suicidal behaviour and related risk factors among school-aged youth in the Republic of Benin. PLoS One. 2014;9: e88233 10.1371/journal.pone.0088233 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Shoval G, Shmulewitz D, Wall MM, Aharonovich E, Spivak B, Weizman A, et al. Alcohol dependence and suicide-related ideation/behaviors in an israeli household sample, with and without major depression. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2014;38: 820–825. 10.1111/acer.12290 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Swahn MH, Bossarte RM, Choquet M, Hassler C, Falissard B, Chau N. Early substance use initiation and suicide ideation and attempts among students in France and the United States. Int J Public Health. 2014;57: 95–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Zhang Y, Conner KR, Phillips MR. Alcohol use disorders and acute alcohol use preceding suicide in China. Addict Behav. 2010;35: 152–156. 10.1016/j.addbeh.2009.09.020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Dunn N, Cook CC. Psychiatric aspects of alcohol misuse. Hosp Med. 1999;60: 169–172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Sher L. Alcohol consumption and suicide. QJM. 2006;99: 57–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Wojnar M, Ilgen MA, Jakubczyk A, Wnorowska A, Klimkiewicz A, Brower KJ. Impulsive suicide attempts predict post-treatment relapse in alcohol-dependent patients. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2008;97: 268–275. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.04.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Conner KR, Hesselbrock VM, Schuckit MA, Hirsch JK, Knox KL, Meldrum S, et al. Precontemplated and impulsive suicide attempts among individuals with alcohol dependence. J Stud Alcohol. 2006;67: 95–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. DeLeo D, Bertolote J, Lester D. Self-directed violence In: Krug EG, Dahlberg LL, Mercy JA, Zwi A, Lozano R, editors. World report on violence and health. Geneva: WHO; 2002: pp. 183–212. [Google Scholar]

- 59. Pompili M, Serafini G, Innamorati M, Dominici G, Ferracuti S, Kotzalidis GD, et al. Suicidal behavior and alcohol abuse. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2010;7: 1392–1431. 10.3390/ijerph7041392 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Fazel S, Benning R, Danesh J. Suicides in male prisoners in England and Wales, 1978–2003. Lancet. 2005;366: 1301–1302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Preti A, Cascio MT. Prison suicides and self-harming behaviours in Italy, 1990–2002. Med Sci Law. 2006;46: 127–134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Szklo M, Nieto FJ. Epidemiology beyond the basics. Sudbury: Jones and Bartlett Publishers; 2007. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(DOC)

Data Availability Statement

All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files.