Abstract

Rationale

Neurosteroids and likely other lipid modulators access transmembrane sites on the GABAA receptor (GABAAR) by partitioning into and diffusing through the plasma membrane. Therefore, specific components of the plasma membrane may affect the potency or efficacy of neurosteroid-like modulators. Here, we tested a possible role for phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate (PIP2), a phospholipid that governs activity of many channels and transporters, in modulation or function of GABAARs.

Objectives

In these studies, we sought to deplete plasma-membrane PIP2 and probe for a change in the strength of potentiation by submaximal concentrations of the neurosteroid allopregnanolone (3α5αP) and other anesthetics, including propofol, pentobarbital, and ethanol. We also tested for a change in the behavior of negative allosteric modulators pregnenolone sulfate and dipicrylamine.

Methods

We used Xenopus oocytes expressing the ascidian voltage-sensitive phosphatase (Ci-VSP) to deplete PIP2. Voltage pulses to positive membrane potentials were used to deplete PIP2 in Ci-VSP-expressing cells. GABAARs composed of α1β2γ2L and α4β2δ subunits were challenged with GABA and 3α5αP or other modulators before and after PIP2 depletion. KV7.1 channels and NMDA receptors (NMDARs) were used as positive controls to verify PIP2 depletion.

Results

We found no evidence that PIP2 depletion affected modulation of GABAARs by positive or negative allosteric modulators. By contrast, Ci-VSP-induced PIP2 depletion depressed KV7.1 activation and NMDAR activity.

Conclusions

We conclude that despite a role for PIP2 in modulation of a wide variety of ion channels, PIP2 does not affect modulation of GABAARs by neurosteroids or related compounds.

Keywords: Anesthetic; Anticonvulsant; Neurosteroid; GABA; Inhibition; Membrane; Phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate

We have shown that anesthetic neurosteroids likely reach their GABAA receptor (GABAAR) target through plasma-membrane partitioning (Akk et al. 2005; Chisari et al. 2009). This idea fits the proposal that the steroid interaction sites on the receptor reside in transmembrane domains (Hosie et al. 2006, 2009; Li et al. 2007). Within a structurally defined set of neurosteroid analogues, the steroid logP (logarithm of the oil-to-water partition coefficient) correlates with fluorescent steroid accumulation, with onset/offset kinetics of GABA modulation, and with potency (aqueous EC50 concentration) of steroid action (Chisari et al. 2010). However, a simple measure of lipophilicity like calculated logP does not account for the complex effects that real biological membranes of varied phospholipid and cholesterol content may have on steroid partitioning and receptor access. If neurosteroids partition into the plasma membrane en route to interacting with the GABAAR, then perturbing critical components of the plasma membrane may affect steroid actions. Indeed, past evidence suggests that membrane cholesterol content may influence the effect of neurosteroids on inhibition (Sooksawate and Simmonds 1998).

Here, we chose to manipulate phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate (PIP2), a critical membrane phospholipid, representing approximately 1 % of total acidic lipid (McLaughlin et al. 2002; Suh and Hille 2008). PIP2 is found principally in the cytoplasmic leaflet of the plasma membrane and represents the most abundant poly-phosphoinositide. Although cleavage of PIP2 by phospholipase C results physiologically in second messengers inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate and diacylglycerol, PIP2 itself is required for or modulates the behavior of many ion channels, including background (leak) channels that give rise to the resting membrane potential, voltage-gated channels responsible for excitability, and ligand-gated ion channels important for neuronal communication (McLaughlin et al. 2002). PIP2 is also an attractive target for experimental perturbation because tools have recently been developed that allow rapid PIP2 depletion (Hertel et al. 2011; Lindner et al. 2011). Thus, receptor/channel behavior can be assessed in the same cell before and after PIP2 depletion.

In this work, we exploited the heterologously expressed ascidian voltage-sensitive phosphatase (Ci-VSP) system (Murata et al. 2005). The Ci-VSP protein combines a transmembrane voltage sensor domain with a cytoplasmic phosphatase with sequence similarity to PTEN. Unlike PTEN or phospholipase C, Ci-VSP dephosphorylates the 5′ phosphate of PIP2 (Iwasaki et al. 2008). Thus, VSP effectively depletes PIP2 in heterologous cells without triggering production of canonical downstream second messengers of the phospholipase C pathway, inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate, and diacylglycerol. Xenopus oocytes have proven a particularly advantageous system for Ci-VSP expression and activation (Murata et al. 2005).

In the present studies, we found that despite evidence for strong PIP2 depletion upon depolarization of Xenopus oocytes expressing Ci-VSP, neither baseline GABAAR function nor neurosteroid modulation of GABAARs was altered. Similarly, we found no evidence that PIP2 depletion affected the activity of other lipophilic modulators of GABAAR function. By contrast, Kv7.1 channels were strongly modulated by Ci-VSP expression and activation. We also demonstrated modulation of behavior of another class of ligand-gated ion channel, NMDA receptors (NMDARs). In summary, despite the ubiquity of PIP2 in modulating ion channel function, PIP2 has no detectable role in the function or modulation of GABAAR activity.

Methods

Oocyte expression

Stage V–VI oocytes were harvested from sexually mature female Xenopus laevis (Xenopus One, Northland, MI) under 0.1 % tricaine (3-aminobenzoic acid ethyl ester) anesthesia, according to protocols approved by the Washington University Animal Studies Committee. Oocytes were defolliculated by shaking for 20 min at 37 °C in collagenase (2 mg ml−1) dissolved in calcium-free solution containing the following (in mM): NaCl (96), KCl (2), MgCl2 (1), and HEPES (5) at pH 7.4.

Constructs were prepared in pcDNA (GABAAR subunits, NMDAR subunits, KCNE1, Kv7.1) or psD64TF (Ci-VSP) plasmids. Capped mRNA, encoding rat GABAAR α1 (or α4), β2, and γ2L (or δ) subunits and Ci-VSP, Kv7.1, KCNE1, GluN1, and GluN2A were transcribed in vitro using the mMESSAGE mMACHINE kit (Ambion, Austin, TX) from linearized vectors containing receptor-coding regions. Subunit transcripts were injected in a volume of up to 50 nl and 50 ng total RNA 16–24 h following defolliculation. Oocytes were incubated up to 5 days at 18 °C in ND96 medium containing the following (in mM): 96 NaCl, 1 KCl, 1 MgCl2, 2 CaCl2, and 10 HEPES at pH 7.4, supplemented with pyruvate (5 mM), penicillin (100 U ml−1), streptomycin (100 μg ml−1), and gentamycin (50 μg ml−1).

Oocyte electrophysiology

Two-electrode voltage-clamp experiments were performed with an OC725 amplifier (Warner Instruments, Hamden, CT) 2–5 days following RNA injection. The extracellular recording solution was ND96 medium with no supplements. Intracellular recording pipettes were filled with 3 M KCl and had open tip resistances of ~1 MΩ. GABA and the modulators were applied from a common tip via a gravity-driven multibarrel delivery system. Unless indicated otherwise, drugs were co-applied with no pre-application period. Except as indicated, cells were voltage-clamped at −70 mV, and the peak current (for potentiated responses) or the current at the end of 30-s drug applications (for inhibition of responses) was measured for quantification of current amplitudes.

Experimental design and analysis

Design of individual experiments is described in the “Results” and figure legends. Wherever possible, each cell served as its own control, and experimental conditions and drug applications were interleaved to negate any time dependent changes in cell responsiveness. Ci-VSP expression was verified in each oocyte prior to challenges with agonists and modulators, using protocols described in Fig. 1.

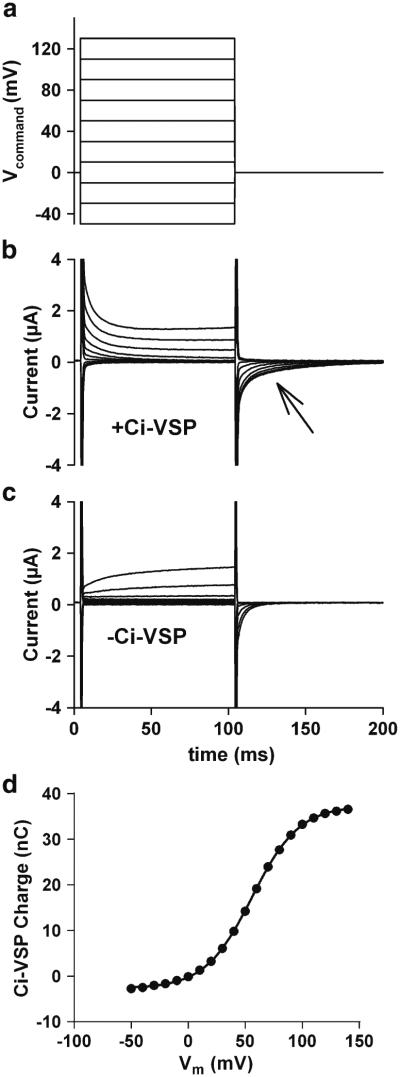

Fig. 1.

Verification of Ci-VSP expression in Xenopus oocytes. For these studies, oocytes were injected with RNA encoding the voltage-sensitive phosphatase (Ci-VSP), composed of a voltage-sensing transmembrane domain and a cytosolic phosphatase domain. Functional expression of the molecule was assayed by eliciting capacitive charge movements (current) associated with conformational changes in the voltage-sensing region. a Voltage-pulse protocol used to elicit capacitive currents. b Current responses from an oocyte expressing Ci-VSP. c Current responses from an oocyte not expressing Ci-VSP. The fast, transient capacitive currents resulting from charge movements across the plasma membrane are present (and truncated for clarity), but not the slower charge movements associated with Ci-VSP. Cells not expressing Ci-VSP also exhibited variable voltage-activated ionic currents that gave rise to fast tail currents during the return pulse. The time calibration in (c) applies to (a–c). d Difference currents were calculated by subtracting the average current responses of five oocytes not injected with Ci-VSP from the average current responses of five sibling oocytes injected with Ci-VSP. The resulting Q/V plot was generated by integrating current during the return step (arrow) beginning 6 ms following the return step to exclude residual, fast, unsubtracted control transients. The plot compares favorably with those previously published for the Ci-VSP response to depolarization (Murata et al. 2005) and suggests that pulses above 0 mV should activate the phosphatase. The solid line indicates a fit to the Boltzmann equation and yielded estimates of V1/2 of 56.1 mV and an equivalent charge of 1.2

Data acquisition and analysis were performed with the pCLAMP 9.0 software (Molecular Devices, Union City, CA). Data plotting was accomplished with the SigmaPlot 10.0 software (SPSS Science, Chicago, IL). Data are presented in the text and figures as mean ± standard error. Statistical differences were determined using a two-tailed Student’s t test.

Drugs, chemicals, and other materials

Most drugs were from Sigma (St. Louis, MO). Dipicrylamine was from Biotium (Hayward, CA). DS2 was from Tocris Bioscience. GABA and NMDA were prepared as aqueous stock solutions. Steroids and other modulators except ethanol were prepared as stock solutions in dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO). The final DMSO concentration was always below 0.1 %, and solutions were matched for DMSO concentration. Ethanol solutions were prepared fresh and kept covered.

Results

Ci-VSP expression in oocytes was first assessed by measuring capacitive currents generated by voltage pulses to membrane potentials that activate phosphatase activity (Murata et al. 2005). As previously documented, charge movement from conformational changes associated with the voltage sensor was detectable at membrane potentials more positive than ~0 mV (Fig. 1a–d). Cells not injected with Ci-VSP had only rapid capacitive transients attributable to the membrane bilayer and exhibited variable ionic currents activated with a delay (Fig. 1c). In Ci-VSP-injected cells, capacitive charge movements upon return voltage pulses (arrow Fig. 1b), compared with non-expressing oocytes, suggested that ~40 nC of charge was attributable to Ci-VSP with the strongest voltage pulses (Fig. 1c). These capacitive current levels compare well with Ci-VSP expression levels in previous studies utilizing Ci-VSP to deplete PIP2 (Iwasaki et al. 2008; Lindner et al. 2011; Murata et al. 2005).

To determine the effectiveness of phosphatase activity in modulating channel activity, we exploited Kv7.1, coexpressed with KCNE1. Together, these two subunits form the major components of cardiac I(Ks). KCNE1 is a modulatory auxiliary subunit for the Kv7.1 pore-forming subunit (Wrobel et al. 2012). KCNE1 is thought to account for the characteristic slow I(Ks) activation, possibly by interacting with voltage sensing of the Kv7.1 channel (Wu et al. 2010; Zaydman et al. 2013). In oocytes triply injected with Ci-VSP, Kv7.1, and KCNE1, we used a 2-s voltage pulse to +20 mV to activate Kv7.1 currents (Fig. 2a, b). This potential was chosen to yield significant Kv7.1 current with limited activation of Ci-VSP (Fig. 2c (Murata and Okamura 2007)). After a baseline Kv7.1 current was elicited, the membrane potential was pulsed to +40 mV for 60 s. This was sufficient to nearly eliminate Kv7.1 current, leaving only passive leak current evident (Fig. 2a). Several minutes (6 min typically) at −80 mV produced full recovery of Kv7.1 currents.

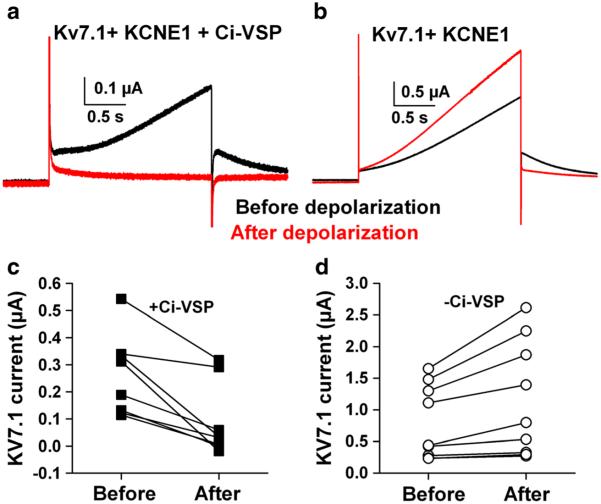

Fig. 2.

Verification of enzymatic activity. All oocytes were injected with RNA encoding Kv7.1 and the auxiliary subunit KCNE1. In addition, half of the oocytes were injected with Ci-VSP. a In an oocyte co-expressing Ci-VSP, outward current was slowly activated by a pulse to +20 mV (black trace). The outward current was suppressed by a prolonged pulse to +40 mV, leaving a small amount of outward leak current (red trace). b By contrast, in an oocyte not co-expressing Ci-VSP, the conditioning depolarization slightly increased the outward Kv7.1 current. c and d Summary data from six Ci-VSP co-injected oocytes and seven oocytes lacking Ci-VSP. Leak currents were not subtracted and account for most of the residual outward current following conditioning in Ci-VSP-injected oocytes. Note the difference in scales for panels (c) and (d), suggesting some suppression of Kv7.1 current even at baseline

By contrast, control cells injected only with KCNE1/Kv7.1 (but no Ci-VSP) showed slight run-up (rather than depression) of Kv7.1 current (Fig. 2b). The basis for the trend toward larger Kv7.1 currents in control oocytes is not clear, but these experiments clearly demonstrate the effectiveness of Ci-VSP activation with pulses to +40 mV for reducing/depleting PIP2 levels. Depolarizing pulses as brief as 5 s were as effective in reducing Kv7.1 currents as 60-s pulses (N=8). When we repulsed the membrane potential to +20 mV at varying intervals following PIP2 depletion, we found that KV7.1 currents remained completely suppressed at 30 s following depletion (−0.08±0.06 normalized Kv7.1 current relative to baseline, N=3) but had recovered variably by 60 s (0.37±0.09, N=12) and nearly fully by 3 min (0.87±0.19, N=16). In addition to the within-cell differences following depolarization, we noted that oocytes co-injected with Ci-VSP had smaller baseline Kv7.1 currents than those not injected with Ci-VSP (Fig. 2c, d). This likely reflects, at least in part, some degree of phosphatase activation with the pulse designed to elicit Kv7.1 current. Taken together, these results suggest robust depletion of PIP2 with brief pulses to +40 mV, and PIP2 levels remain depressed for several minutes.

Our previous work has suggested that anesthetic neurosteroids must partition into the plasma membrane prior to accessing the GABAAR (Akk et al. 2005; Chisari et al. 2009). Others have shown that the GABAAR-steroid interaction sites are within the transmembrane domains of the receptor protein near the cytosolic face (Hosie et al. 2007, 2009). In addition, PIP2 is important for basal activity and for modulation of a variety of voltage-gated and ligand-gated ion channels (Suh and Hille 2008). Therefore, we proceeded to test whether anesthetic neurosteroid modulation of GABAARs depends on membrane PIP2 levels. We assessed neurosteroid modulation before and after a PIP2-depleting voltage pulse to +40 mV. During intervening periods, oocytes were clamped to −80 mV to regenerate PIP2. In order to detect either an increase or a decrease in neurosteroid potentiation, we employed a moderately low concentration of the neurosteroid 3α5αP (100 nM) (Fig. 3a). We and others have previously shown that in oocytes expressing α1β2γ2L receptors, this concentration is sub-EC50 (Wafford et al. 1996; Wang et al. 2002). In nine oocytes co-injected with the GABAAR subunit combination plus Ci-VSP, potentiation by 100 nM 3α5αP was 3.0±0.4 (normalized to GABA alone) prior to strong depolarization and 3.4±0.4 immediately following strong depolarization (N=9 oocytes, p>0.05). This potentiation value was also not significantly different than those observed in oocytes injected with GABAAR subunits only (2.9±0.2 before depolarization, 2.8±0.3 after depolarization N=6).

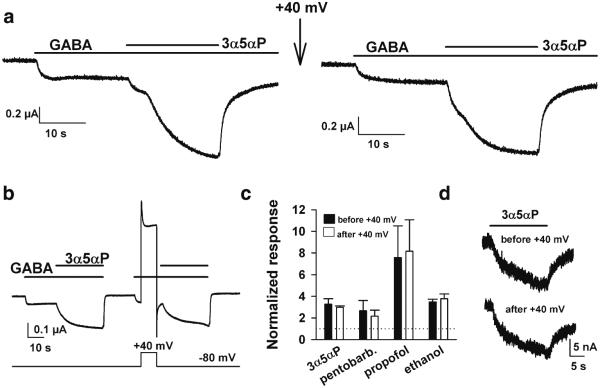

Fig. 3.

Anesthetic neurosteroids and other GABAAR modulators are unaffected by PIP2 depletion. Oocytes were injected with rat α1β2γ2L subunits of the GABAAR and co-injected with Ci-VSP. a An oocyte co-injected with Ci-VSP was challenged with GABA (2 μM) then with co-application of 0.1 μM 3α5αP, as indicated by the horizontal bars (left panel). Cells were then conditioned with a PIP2-depleting pulse to + 40 mV (arrow). The same oocyte responded similarly following the PIP2-depleting pulse (right panel). b A different protocol was designed to minimize the time between PIP2-depleting stimulus and assay of potentiation. There was still no detectable alteration in potentiation. c Summary of responses of three to four oocytes challenged with each of the indicated potentiators: 3α5αP (100 nM), pentobarbital (50 μM), propofol (1 μM), and ethanol (200 mM). d Direct gating of GABAA receptors is unaffected by PIP2 depletion. Five µM 3α5αP was applied prior to and 10 s following a 10 s pulse to +40 mV in an oocyte expressing Ci-VSP

Although steroid testing occurred within 1 min of PIP2 depletion, results with Kv7.1 suggested that variable replenishment of PIP2 occurs within this time frame (see above). To ensure that recovery did not contaminate our ability to observe a change in neurosteroid potentiation, we designed a protocol to deliver the PIP2-depleting stimulus temporally closer to steroid application (Fig. 3b). In this case, we still did not observe a change in steroid potentiation (Fig. 3b, c). In addition, we tested three other anesthetics with actions at GABAARs: pentobarbital, propofol, and ethanol (Fig. 3c). Ethanol and propofol have both been suggested to interact with the transmembrane domains of the receptor, although proposed sites are near the extracellular membrane leaflet (Howard et al. 2011; Sauguet et al. 2013; Yip et al. 2013). We found no effect of PIP2 depletion on potentiation of GABA currents by any of these potentiators. Finally, we tested whether direct gating by 3α5αP was affected by PIP2 depletion. Responses to 5 μM 3α5αP (in the absence of GABA) were unaffected by a pulse to +40 mV immediately preceding steroid application (ratio of response following PIP2-depleting pulse to response preceding PIP2-depleting pulse: 1.04±0.12, N=5 oocytes; Fig. 3d).

Although the anesthetic steroid site involves the same residues and mechanism at all major GABAAR subunit combinations (Hosie et al. 2009), δ subunit containing GABAARs have particular sensitivity to steroids, mainly resulting from the low GABA efficacy of these receptors (Brown et al. 2002; Carver and Reddy 2013; Shu et al. 2012). GABAARs containing the δ subunit have particular importance in generating tonic, non-synaptic GABA currents in certain cell types (Farrant and Nusser 2005; Glykys et al. 2008). We tested whether steroid sensitivity of α4/δ-containing GABAARs is PIP2 sensitive by expressing α4β2δ subunits in oocytes and subjecting oocytes to the protocol shown in Fig. 3b. In oocytes co-expressing this GABAAR subunit combination with Ci-VSP, 3α5αP (0.5 μM) potentiation of responses to 1 μM GABA was 2.8±0.3-fold before PIP2 depletion, 2.3±0.3 after depletion (N=7, not significantly different). For comparison, oocytes expressing α4β2δ subunits without Ci-VSP exhibited potentiation values of 2.8±0.4 before depolarization and 2.7± 0.3 after depolarization (N=6). In all cases, we verified δ subunit expression by testing the sensitivity of GABA responses to the δ-selective potentiator DS2 (1 μM) (Shu et al. 2012; Wafford et al. 2009). In summary, we could discern no effect of PIP2 depletion on 3α5αP sensitivity in δ-containing receptors.

Sulfated neurosteroids and other hydrophobic anions non-competitively antagonize GABAAR function through an activation-dependent mechanism (Eisenman et al. 2003; Shen et al. 2000). The sites for antagonism have not been identified, although a mutation on the cytoplasmic side of M2 eliminates antagonism, presumably by preventing the conformational changes that underlie the antagonism (Akk et al. 2001). In addition, several of these blockers alter membrane capacitance (Chisari et al. 2011; Mennerick et al. 2008), an effect that could be related directly or indirectly to antagonism of receptor function. To determine if PIP2 alters the GABAAR effects of antagonistic neurosteroids and related compounds, we again surveyed the effect of PIP2 depletion immediately prior to negative modulator addition (Fig. 4a). As with positive modulation, we found that negative modulation was unaffected by PIP2 depletion (Fig. 4b). This was true of the neurosteroid pregnenolone sulfate and of the mechanistically similar compound, dipicrylamine (Chisari et al. 2011).

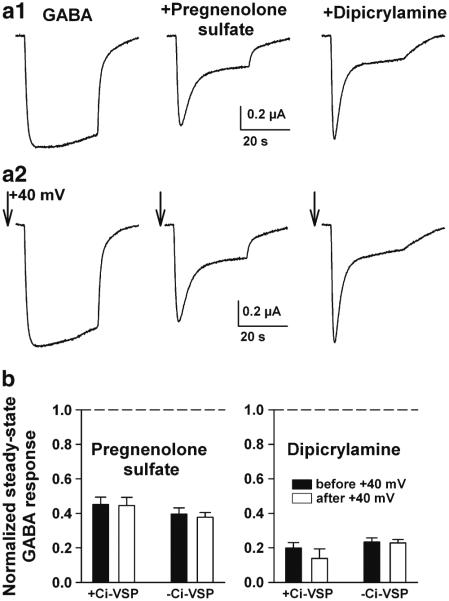

Fig. 4.

Negative steroid modulators and a mechanistically similar compound are unaltered by PIP2 depletion. As in Fig. 3, oocytes were co-injected with Ci-VSP and with GABAAR subunits. Some oocytes were not Ci-VSP injected. a1 Responses to GABA (10 μM) alone and to co-applied negative modulators, pregnenolone sulfate (1 μM) and dipicrylamine (0.5 μM). The modulators have a desensitizing profile characteristic of this class of activation-dependent antagonist (Chisari et al. 2011; Eisenman et al. 2003). a2 PIP2-depleting pulses (arrows) were delivered immediately preceding each response. Neither the GABA responses nor the modulation was appreciably affected. b Steady-state suppression of GABA responses in 12–14 oocytes co-injected with Ci-VSP and GABAAR subunits. Suppression was measured before the PIP2-depleting pulse (solid bars) and immediately after (open bars), in both Ci-VSP-co-injected oocytes (+Ci-VSP) and in sibling oocytes not co-injected (−Ci-VSP)

To ensure that PIP2 depletion could affect subtle aspects of ligand-gated ion channel function, we examined NMDARs, whose activation has been demonstrated to be weakly sensitive to PIP2 (Michailidis et al. 2007). We expected PIP2 depletion to reduce NMDA-activated currents in oocytes expressing GluN1/GluN2A NMDA receptor subunits (Michailidis et al. 2007). Indeed, we found that a PIP2-depleting pulse reduced currents in response to 30 μM NMDA in Ci-VSP-co-injected oocytes, but not in control oocytes not co-injected with Ci-VSP (Fig. 5a–c). Because variable desensitization rates during NMDA application at the time of voltage change could affect these results, we employed an alternative protocol. In a separate set of oocytes, we simply examined the ratio of outward NMDA-induced current, at a potential expected to deplete PIP2, to inward current obtained at −70 mV, where little PIP2 depletion is expected. We found that the ratio of outward current to inward current was smaller in Ci-VSP-expressing cells than in non-expressing cells (Fig. 5d–f). The altered ratio did not result from a difference in NMDAR reversal potential in Ci-VSP-expressing cells. In voltage-ramp tests of the reversal potential, we found that NMDA currents in control oocytes had a reversal potential of −3.4±0.07 mV (N=7) and −9.1±2.5 mV (N=8, p=0.07) in Ci-VSP cells. Although there was a trend toward a more negative reversal potential in PIP2-depleted cells, this trend would work toward a higher outward/inward current ratio, opposite of our observation.

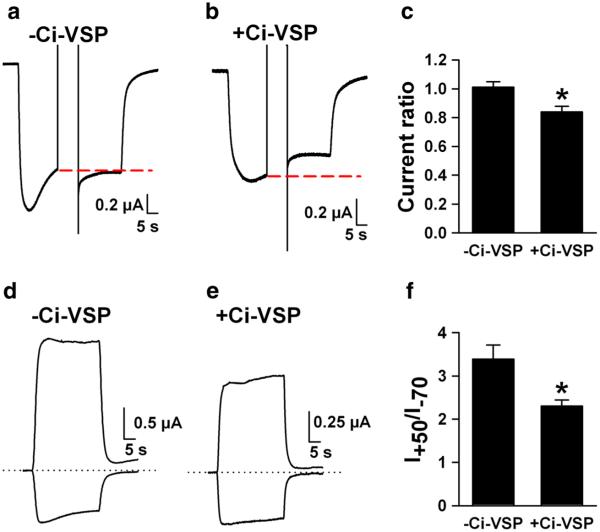

Fig. 5.

PIP2 modulation of NMDA receptors. Oocytes were injected with RNA encoding the NMDA receptor subunits GluN1 and GluN2A. a–c Responses to 30 μM NMDA (inward currents) were obtained from control oocytes injected with NMDAR subunits alone (a) or co-injected with Ci-VSP (b) and challenged with a pulse to +40 mV during the NMDA application (indicated by disruption in the inward NMDA current). The red dashed line indicates the current level just prior to the PIP2-depleting conditioning pulse. NMDA current is reduced in the +Ci-VSP oocyte (b) but not in the control oocyte (a). Summary bar graph reflects 10 Ci-VSP injected oocytes and 10 control oocytes. Current ratio refers to the ratio of current at the end of the NMDA application, following the +40 mV pulse, compared with the current level just prior to the pulse. d–f A different protocol in an independent sample of oocytes in which the ratio of outward NMDA-evoked current at +50 mV was measured relative to inward NMDA-evoked current at −70 mV. PIP2 depletion at the positive potential resulted in reduced +50/−70 mV current ratio (N=6 Ci-VSP and 6 control oocytes)

Discussion

Over the past 10 years, PIP2 has been shown to govern or modulate the function of a variety of background leak channels (Kir channels, two-P domain channels), voltage-gated channels (voltage-gated Ca2+ channels, voltage-gated K+ channels), ligand-gated channels (TRP channels, P2X receptors, NMDA receptors), and transporters/exchangers (Michailidis et al. 2007; Suh and Hille 2008). Nevertheless, our study demonstrates resistance of one class of ligand-gated ion channel, GABAARs, to PIP2 depletion. Neither basal function nor positive or negative modulation by a variety of lipophilic allosteric modulators was affected in our experiments. Direct gating by the positively modulating steroid 3α5αP was also unaffected. By extension, it seems likely that other cys-loop family members may also be resistant to PIP2 modulation.

Classically, PIP2 cleavage by mammalian phospholipases, most notably phospholipase C, gives rise to second messengers inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate and diacylglycerol. These messengers, in turn, alter the function of other proteins and channels through downstream cascades. The more recent discoveries highlighted above demonstrate the critical role that PIP2 itself has in maintaining and/or modulating channel and transporter function. In some cases, a direct binding site for PIP2 has been demonstrated; in other cases, the mechanism for PIP2 modulation remains unclear and could involve changes in lipid bilayer properties (Rusinova et al. 2013). Our study was meant to test a direct or indirect role for PIP2 in GABAAR gating and modulation.

Several factors should be considered in interpreting the negative results in our study. Our experiments mostly employed the most common GABAAR subunit combination in the brain (α1β2γ2L). It is possible that other less common subunit combinations may be affected differently by PIP2 depletion. However, an α4/δ-containing subunit combination that is highly neurosteroid sensitive yielded similar results in our studies. Further, given that the site of neurosteroid modulation is similar at all subunit combinations (Hosie et al. 2009), it seems likely that our results are broadly representative.

We also employed a single concentration of modulator. We chose concentrations of GABA and modulator designed to yield clearly detectable but submaximum effects, so that either increases or decreases in modulator activity would be readily detected. An exception may be ethanol, which we used at a high concentration of 200 mM. Unfortunately, in our hands, lower concentrations of ethanol yielded potentiation too weak to measure reliably. On balance, neither “floor” nor “ceiling” effects are likely explanations for our negative results.

It also might be argued that our measures may not have been sensitive enough to detect small differences. However, we designed multiple protocols optimized to detect changes, and subtle changes in the function of NMDA receptors were detected with protocols similar to those used to monitor GABAAR modulation. Taken together with the relevant positive controls, the evidence for no effect of membrane PIP2 in neurosteroid modulation of GABAARs is compelling.

Our results do not negate the more general hypothesis that membrane composition is important for the actions of neurosteroids and other lipophilic modulators that may have a membrane route of access. Additional experimental approaches may include manipulating synthesis or breakdown of other phospholipids, extraction of membrane components, or reconstitution of receptors in membranes of defined composition.

In summary, despite the apparent widespread PIP2 modulation of channels and receptors, we find no evidence that this plasma-membrane phospholipid regulates GABAARs. PIP2 is not required for the conformational changes underlying GABA-induced gating, positive allosteric modulation by steroids and other anesthetics, or negative modulation by steroids. By contrast, NMDA receptor gating by agonist is sensitive to PIP2 modulation, as previously documented (Mandal and Yan 2009; Michailidis et al. 2007).

Acknowledgments

We thank Jianmin Cui for the gift of Ci-VSP, Kv7.1, and KCNE1 constructs and Joe Henry Steinbach for the discussion related to the conception of these experiments. Thanks to Hong-Jin Shu for the help in the RNA preparation. This work was funded by a gift from the Bantly Foundation and NIH grants GM47969, MH078823, MH099658, MH077791, and AA017413.

References

- Akk G, Bracamontes J, Steinbach JH. Pregnenolone sulfate block of GABAA receptors: mechanism and involvement of a residue in the M2 region of the α subunit. J Physiol Lond. 2001;532:673–684. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2001.0673e.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akk G, Shu HJ, Wang C, Steinbach JH, Zorumski CF, Covey DF, Mennerick S. Neurosteroid access to the GABAA receptor. J Neurosci. 2005;25:11605–11613. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4173-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown N, Kerby J, Bonnert TP, Whiting PJ, Wafford KA. Pharmacological characterization of a novel cell line expressing human α4β3δ GABAA receptors. Br J Pharmacol. 2002;136:965–974. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0704795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carver CM, Reddy DS. Neurosteroid interactions with synaptic and extrasynaptic GABA(A) receptors: regulation of subunit plasticity, phasic and tonic inhibition, and neuronal network excitability. Psychopharmacology (Berlin) 2013;230:151–188. doi: 10.1007/s00213-013-3276-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chisari M, Eisenman LN, Krishnan K, Bandyopadhyaya AK, Wang C, Taylor A, Benz A, Covey DF, Zorumski CF, Mennerick S. The influence of neuroactive steroid lipophilicity on GABAA receptor modulation: evidence for a low-affinity interaction. J Neurophysiol. 2009;102:1254–1264. doi: 10.1152/jn.00346.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chisari M, Eisenman LN, Covey DF, Mennerick S, Zorumski CF. The sticky issue of neurosteroids and GABAA receptors. Trends Neurosci. 2010;33:299–306. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2010.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chisari M, Wu K, Zorumski CF, Mennerick S. Hydrophobic anions potently and uncompetitively antagonize GABAA receptor function in the absence of a conventional binding site. Br J Pharmacol. 2011;164:667–680. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2011.01396.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenman LN, He Y, Fields C, Zorumski CF, Mennerick S. Activation-dependent properties of pregnenolone sulfate inhibition of GABAA receptor-mediated current. J Physiol Lond. 2003;550:679–691. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2003.043810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farrant M, Nusser Z. Variations on an inhibitory theme: phasic and tonic activation of GABAA receptors. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2005;6:215–229. doi: 10.1038/nrn1625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glykys J, Mann EO, Mody I. Which GABAA receptor subunits are necessary for tonic inhibition in the hippocampus? J Neurosci. 2008;28:1421–1426. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4751-07.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hertel F, Switalski A, Mintert-Jancke E, Karavassilidou K, Bender K, Pott L, Kienitz MC. A genetically encoded tool kit for manipulating and monitoring membrane phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate in intact cells. PLoS One. 2011;6:e20855. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0020855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hosie AM, Wilkins ME, da Silva HMA, Smart TG. Endogenous neurosteroids regulate GABAA receptors via two discrete transmembrane sites. Nature. 2006;444:486–489. doi: 10.1038/nature05324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hosie AM, Wilkins ME, Smart TG. Neurosteroid binding sites on GABA(A) receptors. Pharmacol Ther. 2007;116:7–19. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2007.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hosie AM, Clarke L, da Silva H, Smart TG. Conserved site for neurosteroid modulation of GABAA receptors. Neuropharmacology. 2009;56:149–154. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2008.07.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howard RJ, Murail S, Ondricek KE, Corringer PJ, Lindahl E, Trudell JR, Harris RA. Structural basis for alcohol modulation of a pentameric ligand-gated ion channel. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:12149–12154. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1104480108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwasaki H, Murata Y, Kim Y, Hossain MI, Worby CA, Dixon JE, McCormack T, Sasaki T, Okamura Y. A voltage-sensing phosphatase, Ci-VSP, which shares sequence identity with PTEN, dephosphorylates phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:7970–7975. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0803936105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li P, Bracamontes J, Katona BW, Covey DF, Steinbach JH, Akk G. Natural and enantiomeric etiocholanolone interact with distinct sites on the rat α1β2γ2L GABAA receptor. Mol Pharmacol. 2007;71:1582–1590. doi: 10.1124/mol.106.033407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindner M, Leitner MG, Halaszovich CR, Hammond GR, Oliver D. Probing the regulation of TASK potassium channels by PI4,5P(2) with switchable phosphoinositide phosphatases. J Physiol Lond. 2011;589:3149–3162. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2011.208983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandal M, Yan Z. Phosphatidylinositol (4,5)-bisphosphate regulation of N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor channels in cortical neurons. Mol Pharmacol. 2009;76:1349–1359. doi: 10.1124/mol.109.058701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLaughlin S, Wang J, Gambhir A, Murray D. PIP(2) and proteins: interactions, organization, and information flow. Annu Rev Biophys Biomol Struct. 2002;31:151–175. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.31.082901.134259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mennerick S, Lamberta M, Shu HJ, Hogins J, Wang C, Covey DF, Eisenman LN, Zorumski CF. Effects on membrane capacitance of steroids with antagonist properties at GABAA receptors. Biophys J. 2008;95:176–185. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.107.124768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michailidis IE, Helton TD, Petrou VI, Mirshahi T, Ehlers MD, Logothetis DE. Phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate regulates NMDA receptor activity through alpha-actinin. J Neurosci. 2007;27:5523–5532. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4378-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murata Y, Okamura Y. Depolarization activates the phosphoinositide phosphatase Ci-VSP, as detected in Xenopus oocytes coexpressing sensors of PIP2. J Physiol Lond. 2007;583:875–889. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2007.134775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murata Y, Iwasaki H, Sasaki M, Inaba K, Okamura Y. Phosphoinositide phosphatase activity coupled to an intrinsic voltage sensor. Nature. 2005;435:1239–1243. doi: 10.1038/nature03650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rusinova R, Hobart EA, Koeppe RE, 2nd, Andersen OS. Phosphoinositides alter lipid bilayer properties. J Gen Physiol. 2013;141:673–690. doi: 10.1085/jgp.201310960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sauguet L, Howard RJ, Malherbe L, Lee US, Corringer PJ, Harris RA, Delarue M. Structural basis for potentiation by alcohols and anaesthetics in a ligand-gated ion channel. Nat Commun. 2013;4:1697. doi: 10.1038/ncomms2682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen W, Mennerick S, Covey DF, Zorumski CF. Pregnenolone sulfate modulates inhibitory synaptic transmission by enhancing GABAA receptor desensitization. J Neurosci. 2000;20:3571–3579. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-10-03571.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shu HJ, Bracamontes J, Taylor A, Wu K, Eaton MM, Akk G, Manion B, Evers AS, Krishnan K, Covey DF, Zorumski CF, Steinbach JH, Mennerick S. Characteristics of concatemeric GABA(A) receptors containing alpha4/delta subunits expressed in Xenopus oocytes. Br J Pharmacol. 2012;165:2228–2243. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2011.01690.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sooksawate T, Simmonds MA. Increased membrane cholesterol reduces the potentiation of GABAA currents by neurosteroids in dissociated hippocampal neurones. Neuropharmacology. 1998;37:1103–1110. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(98)00113-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suh BC, Hille B. PIP2 is a necessary cofactor for ion channel function: how and why? Annu Rev Biophys. 2008;37:175–195. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.37.032807.125859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wafford KA, Thompson SA, Thomas D, Sikela J, Wilcox AS, Whiting PJ. Functional characterization of human gamma-aminobutyric acidA receptors containing the α4 subunit. Mol Pharmacol. 1996;50:670–678. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wafford KA, van Niel MB, Ma QP, Horridge E, Herd MB, Peden DR, Belelli D, Lambert JJ. Novel compounds selectively enhance δ subunit containing GABAA receptors and increase tonic currents in thalamus. Neuropharmacology. 2009;56:182–189. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2008.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang M, He Y, Eisenman LN, Fields C, Zeng CM, Mathews J, Benz A, Fu T, Zorumski E, Steinbach JH, Covey DF, Zorumski CF, Mennerick S. 3β -hydroxypregnane steroids are pregnenolone sulfate-like GABAA receptor antagonists. J Neurosci. 2002;22:3366–3375. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-09-03366.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wrobel E, Tapken D, Seebohm G. The KCNE tango—how KCNE1 interacts with Kv7.1. Front Pharmacol. 2012;3:142. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2012.00142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu D, Pan H, Delaloye K, Cui J. KCNE1 remodels the voltage sensor of Kv7.1 to modulate channel function. Biophys J. 2010;99:3599–3608. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2010.10.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yip GM, Chen ZW, Edge CJ, Smith EH, Dickinson R, Hohenester E, Townsend RR, Fuchs K, Sieghart W, Evers AS, Franks NP. A propofol binding site on mammalian GABA receptors identified by photolabeling. Nat Chem Biol. 2013;9:715–720. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.1340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaydman MA, Silva JR, Delaloye K, Li Y, Liang H, Larsson HP, Shi J, Cui J. Kv7.1 ion channels require a lipid to couple voltage sensing to pore opening. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:13180–13185. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1305167110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]