Abstract

Background

Neonatal pain and injury can alter long-term sensory thresholds. Descending rostroventral medulla (RVM) pathways can inhibit or facilitate spinal nociceptive processing in adulthood. As these pathways undergo significant postnatal maturation, we evaluated long-term effects of neonatal surgical injury on RVM descending modulation.

Methods

Plantar hindpaw or forepaw incisions were performed in anesthetized postnatal day (P)3 Sprague-Dawley rats. Controls received anesthesia only. Hindlimb mechanical and thermal withdrawal thresholds were measured to 6 weeks of age (adult). Additional groups received pre- and post-incision sciatic nerve bupivacaine or saline. Hindpaw nociceptive reflex sensitivity was quantified in anesthetized adult rats using biceps femoris electromyography, and the effect of RVM electrical stimulation (5-200 μA) measured as percentage change from baseline.

Results

In adult rats with prior neonatal incision (n=9), all intensities of RVM stimulation decreased hindlimb reflex sensitivity, in contrast to the typical bimodal pattern of facilitation and inhibition with increasing RVM stimulus intensity in controls (n=5) (uninjured vs. neonatally-incised, P<0.001). Neonatal incision of the contralateral hindpaw or forepaw also resulted in RVM inhibition of hindpaw nociceptive reflexes at all stimulation intensities. Behavioral mechanical threshold (mean±SEM, 28.1±8g vs. 21.3±1.2g, P<0.001) and thermal latency (7.1±0.4 vs. 5.3±0.3s, P<0.05) were increased in both hindpaws following unilateral neonatal incision. Neonatal perioperative sciatic nerve blockade prevented injury-induced alterations in RVM descending control.

Conclusions

Neonatal surgical injury alters the postnatal development of RVM descending control, resulting in a predominance of descending inhibition and generalized reduction in baseline reflex sensitivity. Prevention by local anesthetic blockade highlights the importance of neonatal perioperative analgesia.

Introduction

Pain and injury during the neonatal period can alter normal development of sensory pathways, resulting in long-term changes in sensory thresholds and responses to future pain.1,2 Reported effects vary depending on the method of evaluation, the intensity of the stimulus, and the time interval between injury and assessment.2 While responses to noxious stimuli may be enhanced,3-5 quantitative sensory testing has demonstrated reduced baseline sensitivity in children many years after neonatal intensive care treatment and/or surgery.4,6-8 Importantly, in preterm children who required surgery in addition to neonatal intensive care, generalized reductions in sensitivity at the thenar eminence were more marked.7 Centrally-mediated alterations in brainstem modulation with upregulation of tonic descending inhibition has been postulated to underlie this global hypoalgesia.3

Laboratory studies confirm similar long-term alterations in sensory processing following neonatal injury.1,2 The neonatal period (first postnatal week in the rodent) has been identified as a critical period during which inflammation9 or surgical injury10 lead to effects not seen following the same injury at older ages.9 Hindpaw carrageenan produces mild inflammation and acute hyperalgesia in neonatal rats, followed by long-term changes in pain sensitivity that include a generalized baseline hypoalgesia, but an enhanced hyperalgesic response to subsequent injury of the same hindpaw.9,11 Similarly, following neonatal plantar hindpaw incision, sensory thresholds of both the previously injured and contralateral hindpaw were elevated to the same degree in adulthood.12 Re-incision of the paw unmasked increased pain sensitivity,10,12 that could be prevented by perioperative sciatic nerve block at the time of the initial injury.10

The generalized baseline hypoalgesia and the localized re-injury induced hyperalgesia following neonatal injury are likely to have different underlying mechanisms as they differ in both time course and distribution. The enhanced response to repeat injury following neonatal hindpaw inflammation9 or surgical incision10 is demonstrable soon after the initial injury. However, the widespread hypoalgesia following neonatal inflammation does not become apparent until much later (postnatal day 34, P34),9 suggesting that maturation of more complex central systems is required for its expression. We have shown that supraspinal centers, notably those in the rostroventral medulla (RVM) that provide important descending facilitatory and inhibitory control of spinal nociceptive systems, do not mature until late in the 4th postnatal week.13-15 These mechanisms may be vulnerable to injury-induced alterations in neural activity.

We hypothesized that neonatal incision alters the normal postnatal development of spinal modulation from the RVM. Our primary outcome was the pattern of facilitation and/or inhibition of spinal reflex excitability produced by different intensities of RVM electrical stimulation in young adult (P40) animals with or without prior neonatal incision. To evaluate the distribution of altered sensory response following neonatal incision, secondary outcomes were long-term changes in behavioral sensory thresholds of both hindpaws, and RVM-induced changes in reflex sensitivity following neonatal incision in the contralateral hindpaw or forepaw. Finally, perioperative local anesthetic blockade of the sciatic nerve at the time of initial injury (pre-incision plus 3x2 h postoperative injections) was used to evaluate the role of primary afferent activity in triggering developmental alterations in RVM function.

Materials and Methods

Animals

Experiments were performed under personal and project licences approved by the Home Office, London, United Kingdom in accordance with the United Kingdom Animal (Scientific Procedures) Act 1986. Litters of Sprague-Dawley rat pups were obtained from the Biological Services Unit, University College London. Pups were divided into equal numbers of males and females, with litters restricted to a maximum of 12. Pups were randomly picked by hand from within same-sex groups, numbered, and alternately assigned to the incision or control group. Experimental groups were distributed across more than one litter to control for potential litter variability. All animals (including dams) were bred in-house from the same colony and exposed to the same environmental conditions throughout development.

For all interventions, animals were kept on a heating pad to maintain body temperature. Care was taken to minimize the duration of maternal separation and handling of pups, which was the same for treatment and littermate control groups. Pups were weaned into same-sex cages at P21, and maintained until 6 weeks of age on a 12 h light/dark cycle at constant ambient temperature with free access to food and water. Animals were coded by an alternate investigator to ensure the experimenter performing behavioral testing (SMW) or electromyography recordings (GJH) was blinded to treatment allocation at the time of data collection and initial analysis. Data sets for behavioral testing at different time points or electromyography recordings at different intensities were complete. One animal from the contralateral incision group was excluded due to technical difficulties with electromyography recordings.

Plantar Incision

On postnatal day 3 (P3), animals were anesthetized with halothane (2-4%) in oxygen delivered via a nose cone. Alcoholic chlorhexidine gluconate 0.5% (Vetasept, Animalcare Ltd., York, United Kingdom) was applied to the left hindpaw. Following a midline incision through the skin and fascia of the plantar aspect of the hindpaw, the plantaris muscle was elevated and incised longitudinally as previously described.16 The incision extended from the midpoint of the heel to the proximal border of the first footpad.10 Skin edges were closed with a 5-0 silk suture (Ethicon, Edinburgh, United Kingdom). In additional experiments, incision of the plantar skin and underlying muscle of the left forepaw was performed. The size of the forepaw and hindpaw are more closely matched in pups, and the forepaw incision was extended slightly into the distal forelimb to achieve the same length of the incision as in the hindpaw.

Sciatic Nerve Blockade

P3 pups were briefly anesthetized with halothane (2-4%) in oxygen delivered via a nose cone and percutaneous sciatic nerve injections of 40 μl of 0.5% levobupivacaine (Chirocaine 50mg/10ml; Abbott Laboratories Limited, Maidenhead, Berkshire, United Kingdom) were performed as previously described in rat pups.10,17 Following recovery from anesthesia, effective sciatic block was confirmed by ipsilateral motor block and loss of withdrawal reflex response to a suprathreshold mechanical stimulus delivered by a von Frey hair (vFh) with a bending force of 13g. Pups were then re-anesthetized and plantar incision was performed within 15 min of the block. As sciatic blockade is relatively short-lived in rat pups, a preoperative block plus three percutaneous injections at 2 h intervals were performed to maintain afferent blockade during the early perioperative period as previously described.10 Littermate control animals received an injection of 40 μl sterile saline at the same site and intervals.

Behavioral Testing

In neonatal rats, mechanical withdrawal thresholds were measured with hand-held vFh that apply a logarithmically increasing force (vFh 5 = 0.13g to vFh 13 = 7.8g). Rats were lightly restrained on a flat bench surface and ascending intensity hairs applied five times at one-second intervals to the dorsal surface of the hindpaw as previously described.10,18 The number of evoked flexion reflexes was recorded with each stimulus intensity, until a stimulus that evoked five (100%) withdrawal responses was reached.

From P14, mechanical withdrawal threshold and thermal withdrawal latency were determined at weekly intervals to 6 weeks of age. Following habituation on an elevated mesh platform, a mechanical stimulus (electronic von Frey device; Dynamic Plantar Anesthesiometer, Ugo Basile, Comerio, Italy) was applied to the plantar surface of the hindpaw. A linear increase in force was applied with a ramp of 20 grams/second to a maximum of 50g and the threshold was defined as the mean of three measures. Thermal withdrawal latency was determined using a modified Hargreaves Box (University Anesthesia Research and Development Group, University of California San Diego, La Jolla, CA),19 consisting of a glass surface (maintained at 30 °C) on which the rats were placed in individual Plexiglas cubicles. The thermal nociceptive stimulus from a focused projection bulb positioned below the glass surface was directed to the mid-plantar hindpaw. Latency was defined as the time required for the paw to show a brisk withdrawal as detected by photodiode motion sensors that stopped the timer and terminated the stimulus. The stimulus was terminated if there was no response within 20 s (cut-off time).

In-vivo Electrophysiology

The experimental set-up for electrophysiology recordings is shown diagramatically in figure 1A and is in accordance with our previous studies.13,14 Animals were anesthetized with isoflurane (2-4%) in oxygen, an endotracheal cannula was inserted for controlled ventilation (Small Animal Ventilator, Harvard Apparatus Ltd., Kent, United Kingdom), and following mounting on a stereotaxic frame (Kopf Instruments, Tujunga, CA) the skull was exposed and bregma located. Stereotaxic coordinates for the RVM were calculated (P40: Left-Right 0 mm, Antero-Posterior 9.7 mm, Dorsal-Ventral −10 mm) and a small hole was drilled in the skull. For electrical stimulation, concentric bipolar stimulating electrodes were lowered into the RVM using the coordinates above. Trains of stimuli of 500 μsec pulse width were applied at 10Hz, at amplitudes ranging from 5 to 200 μA (Neurolog System, Digitimer Ltd., Welwyn Garden City, United Kingdom).

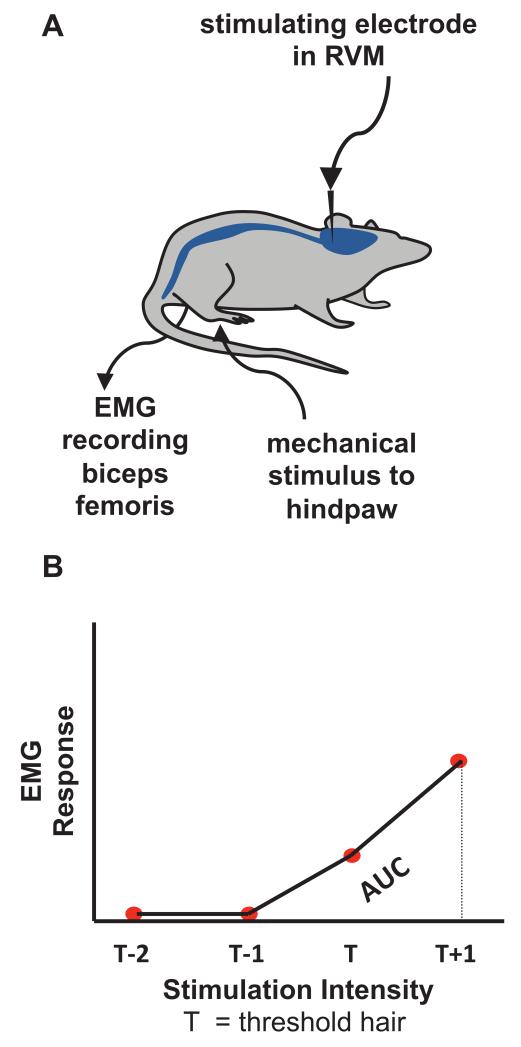

Fig. 1.

(A) Schematic diagram illustrating the experimental set-up. A stimulating electrode was placed in the rostroventral medulla (RVM) of lightly anaesthetised rats, with electromyography (EMG) recording electrodes inserted into biceps femoris. Before and during RVM stimulation, hindpaws were mechanically stimulated with von Frey hairs and evoked EMG responses were recorded. (B) Quantification of overall reflex response. Von Frey hairs of increasing intensity were applied until an increase in EMG activity 10% greater than background was evoked. This hair was designated the threshold hair (T). EMG responses to two subthreshold (T-2 and T-1) and one suprathreshold hair (T+1) were quantified from the average of three applications and plotted against stimulus intensity to generate a baseline stimulus-response profile. The area under this curve (AUC) was then calculated to quantify overall reflex response and spinal excitability.

Following surgical preparation, electromyography recordings were performed as previously described.13 A bipolar concentric needle electrode (Ainsworks, London, United Kingdom) was inserted in the lateral biceps femoris through a small skin incision, to ensure that recorded activity was restricted to local muscle activity. The inspired isoflurane concentration was then reduced to 1.5% (Univentor 400 Anesthesia Unit, Malta), 20 min was allowed for equilibration prior to recording, and the concentration then maintained at this same level throughout. Flexion electromyography (full-wave rectified) responses following sequential (lowest to highest intensity) vFh stimulation of the plantar surface of the hindpaw were processed (Digitimer Ltd.) and recorded (PowerLab 4S, AD Instruments, Castle Hill, Australia). Thresholds were determined as the vFh which produced an electromyography response that was 10% greater than resting activity.

Electromyography responses to two sub-threshold vFh (T-1, T-2), the threshold hair (T) and a suprathreshold hair (T+1) were recorded and the same four hairs used in all subsequent stimulation conditions in that animal. Each hair was applied three times and the mean response for each of the three presentations calculated. A stimulus response curve of electromyography response versus mechanical stimulus intensity was plotted and the area under the curve (AUC) was calculated to provide an integrated measure of the spinal “reflex excitability” (fig. 1B). This value was denoted the baseline response of the animal (AUC=100%). Subsequent recordings during RVM stimulation were normalized to this baseline to encompass any differences in background (non-evoked) electromyography activity and to allow each animal to act as its own control. Facilitation was demonstrated by an increase in AUC which could be several magnitudes greater than the baseline response (e.g., up to 500%), and inhibition as a decrease below baseline, such that the lowest value of −100% represents a loss of reflex response to both the previously threshold and suprathreshold hair.

Statistical Analysis

Sample size estimations were based on our previously published analyses using the same methodology in animals from the same in-house colony and supplier. Significant acute decreases in hindpaw mechanical threshold following P3 incision were reported with n=5,10 and a larger sample was utilized here as forepaw thresholds had not previously been evaluated. Thresholds before and after P3 incision were compared with paired two-tailed Students’ t-test (GraphPad Prism Version 6, San Diego, CA). We have previously reported differences in adult mechanical withdrawal threshold and thermal latency between prior P3 incision and age-matched control animals with n=8.12 Behavioral data were normally distributed (D’Agostino and Pearson normality test) and changes in sensory thresholds were analyzed by factorial repeated measures ANOVA with between-subject (incision versus non-incised control) and within-subject (ipsilateral and contralateral paw at repeated time points from 2 to 6 weeks) variables and Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons. Effects of sex on sensory thresholds at 6 weeks of age was also analyzed by factorial ANOVA with ipsilateral or contralateral paw as the within-subject variable, and sex and incision group as between-subject variables (IBM® SPSS® Statistics Version 22, Portsmouth, Hampshire, United Kingdom).

Electromyography data was expressed as percentage change in reflex response from baseline at each stimulus intensity, with positive values indicating facilitatory and negative values representing inhibitory modulation by RVM stimulation. We have previously demonstrated statistically significant within-group changes in reflex excitability across the same range of stimulus intensities (n=4-6) and smaller sample sizes have demonstrated clear differences in the pattern of facilitation and inhibition at different ages.13,20 Changes in reflex response were compared with two-way ANOVA with RVM stimulation intensity as within-subject repeated measures and treatment group as between-subject variables followed by Bonferroni post-hoc comparisons with each P value adjusted to account for multiple comparisons (GraphPad Prism Version 6, San Diego, CA). P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Neonatal hindpaw incision alters the pattern of descending modulation of spinal excitability from the RVM in early adulthood

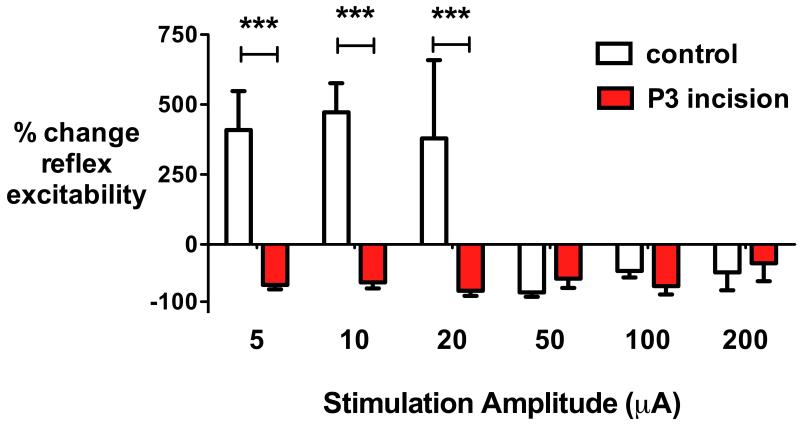

As we have previously shown that the pattern of RVM descending control changes during postnatal maturation, with the typical adult bimodal pattern of facilitation or inhibition emerging after P25,13,15 we assessed the impact of neonatal injury on the pattern of RVM descending modulation in adulthood. In accordance with previous results,13 electrical stimulation of the RVM in control, uninjured adult (P40, n=5) rats facilitated hindlimb mechanical reflex excitability at low stimulation intensities (5-20 μA) and inhibited reflex response at higher intensities (50-200 μA)(fig. 2). By contrast, in adult rats with prior hindpaw incision injury at P3 (n=9), electrical stimulation of the RVM over the same range of current intensities produced only inhibition of reflex excitability. A main effect of neonatal incision (F1,12=18.40, P=0.0011) and stimulus intensity (F5,60=8.03, P<t0.001) was seen, with significant differences in reflex excitability between injured and non-injured groups at low RVM stimulation amplitudes (5 μA, 10 μA and 20 μA)(P<t0.001, two-way repeated measures ANOVA with incision group and stimulus intensity as variables followed by Bonferroni post-hoc comparisons; fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Neonatal injury alters the spinal reflex response to rostroventral medulla (RVM) stimulation. Electrical stimulation of the RVM in naive adult rats (control, n=5) produces a biphasic pattern of change in reflex excitability. Spinal reflex excitability (quantified as the percentage change from baseline in the area under the mechanical stimulus vs electromyography response relationship) is facilitated by low intensity stimulation (5, 10 and 20 μA), and inhibited at high intensities (50, 100 and 200 μA). In age-matched adults with prior plantar hindpaw incision on postnatal day 3 (P3 incision, n=9), all intensities of RVM stimulation inhibit reflex responses at P40. Bars = mean±SEM, ***P<0.001 two-way repeated measures ANOVA with treatment as between-group variable and stimulus intensity as within-group repeated measures followed by Bonferrroni post-hoc comparisons.

Neonatal hindpaw incision produces acute hyperalgesia but generalized hypoalgesia emerges after P28

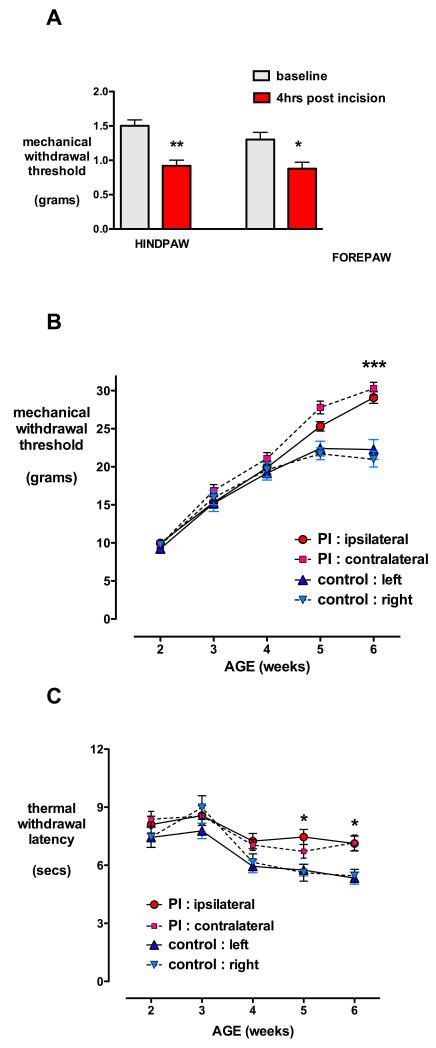

As we wished to evaluate changes in RVM modulation following either hindpaw or distant forepaw incision, we initially confirmed that both injuries produce comparable hyperalgesia. Baseline mechanical withdrawal thresholds were similar in the hindpaw and forepaw (1.50 ± 0.09 vs. 1.47 ± 0.16g; n=12 both groups, t22=0.15, P=0.88; unpaired two-tailed Students t-test). Mechanical withdrawal threshold was significantly decreased 4 h following either hindpaw (1.5 ± 0.09 vs. 0.92 ± 0.08g, n=12, t11=7.39, P<0.01) or forepaw incision (1.31 ± 0.11 vs. 0.88 ± 0.09g; n=7; t6=2.75, P=0.03; paired two-tailed Students t-test; fig. 3A).

Fig. 3.

Neonatal paw incision produces acute hyperalgesia but long-term generalized hypoalgesia. (A) Hindpaw or forepaw mechanical withdrawal thresholds were significantly reduced from baseline 4 h following plantar incision of postnatal day (P) 3. Bars=mean±SEM, n=7 per group, **P<0.01, *P<0.05 paired two-tailed Students t-test.

(B) Hindpaw mechanical withdrawal threshold and (C) thermal withdrawal latency are plotted against age following plantar hindpaw incision (PI) performed on postnatal day (P)3 (n=24), and in littermate non-incised controls (n=12). At 6 weeks of age, mechanical withdrawal thresholds and thermal withdrawal latencies were significantly increased in both the ipsilateral and contralateral paws following P3 incision when compared to age-matched controls. Data points = mean±SEM, ***P<0.001, *P<0.05 factorial repeated measures ANOVA with treatment as between-group variable and both time and paw as within-subject variables followed by Bonferrroni post-hoc comparisons.

To assess the time course and distribution of persistent changes in sensory threshold, hindlimb mechanical and thermal behavioral thresholds were compared from 2 to 6 weeks of age. We previously demonstrated resolution of acute mechanical hyperalgesia by 48 h following P3 incision,10 and here no differences were seen between prior incision (n=24) or littermate control (n=12) groups at 2 weeks (factorial repeated-measures ANOVA with time and paw as within-subject variables and incision as between-subject variable followed by Bonferroni post-hoc comparisons; fig. 3B).

Mechanical withdrawal thresholds progressively increase with age,9,21 and there was a significant main effect of time (F4,136=203, P<0.001) but not paw (F1,34=28, P=0.055) as values did not differ between ipsilateral and contralateral paws in either group (within-subject variables in factorial repeated measures ANOVA). However, mechanical withdrawal thresholds were significantly influenced by prior incision (F1,34=67.7, P<0.001) with delayed onset generalized hypoalgesia apparent in both the ipsilateral and contralateral paw at 6 weeks of age (P<0.001; factorial repeated measures ANOVA with Bonferroni post-hoc comparisons; fig. 3B).

Similar group effects were seen in thermal sensitivity with a main effect of prior incision (F1,34=10.92, P=0.002), and generalized hypoalgesia apparent at 5 and 6 weeks (P<0.05, factorial repeated measures ANOVA with Bonferroni post-hoc comparisons; fig. 3C). Thermal latencies were influenced by time (F4,136=13.86 P<0.001) but ipsilateral and contralateral values did not differ within each treatment group (F1,34=0.259 P=0.614; within-subject variable, factorial repeated measures ANOVA).

Sensory thresholds in male (n=12 previously incised, n=6 control) and female (n=12 previously incised, n=6 control) animals were compared at 6 weeks of age. There was a main effect of prior incision on both mechanical threshold (F1,32=74.3 P<0.001) and thermal latency (F1,32=10.37 P=0.003), but no main effect of sex on mechanical threshold (F1,32=0.43, P=0.52) or thermal latency (F1,32=0.24, P=0.63; factorial ANOVA with incision and sex as between-subject and ipsilateral/contralateral paw as within-subject variables). Male and female data were combined in all other analyses.

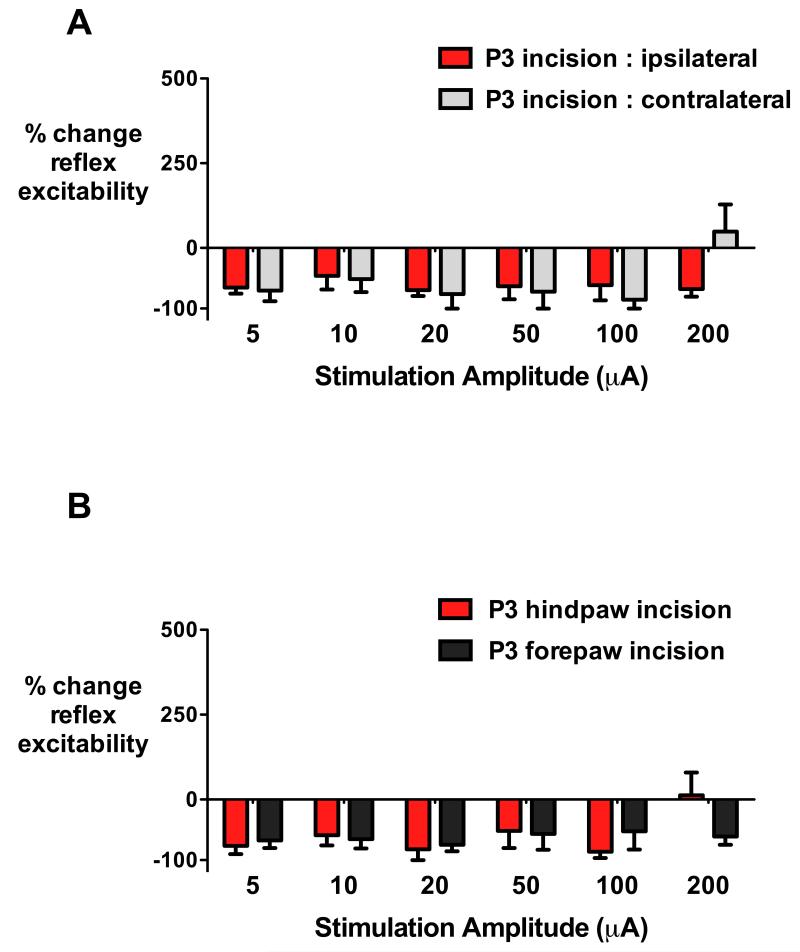

Altered reflex responses to RVM stimulation are also not restricted to the previously injured hindpaw

To determine if the impact of neonatal incision upon RVM descending control of nociceptive reflexes was also generalized and not restricted to the previously injured hindpaw, we next evaluated reflex excitability in the hindpaw following prior incision of the contralateral hindpaw or forepaw. RVM stimulation produced inhibition of spinal reflex excitability, whether the reflex was evoked from a previously injured ipsilateral hindpaw (n=5) or from an adult hindpaw contralateral to a P3 incision (n=3) (fig. 4A). There was no main effect of prior incision site (F1,6=0.22, P=0.655) and a minor effect of stimulus intensity due to variability at 200 μA (F5,30=2.58, P=0.047; two-way ANOVA with incision group as between-subject and stimulus intensity as repeated within-subject variable).

Fig. 4.

Alterations in rostroventral medulla (RVM) modulation following neonatal incision are not limited to the initial injury site.

(A) Following hindpaw incision on postnatal day (P)3, all intensities of electrical stimulation (5 - 200μA) of the RVM produce inhibition of reflex excitability when mechanical stimuli were applied to either the ipsilateral previously injured hindpaw (P3 incision: ipsilateral, n=5) or the contralateral uninjured hindpaw (P3: contralateral, n=3) in early adulthood (P40).

(B) Incision of the forepaw (P3 forepaw incision, n=4) or hindpaw (P3 hindpaw incision, n=4) resulted in the same pattern of hindlimb reflex inhibition across all intensities RVM stimulation at P40. Bars=mean±SEM, no significant differences between treatment groups, two way repeated measures ANOVA with incision group as between-subject and stimulus intensity as repeated within-subject variable followed by Bonferrroni post-hoc comparisons.

Furthermore, when the site of the neonatal P3 plantar incision was changed to the forepaw (n=4), electrical stimulation of the RVM at P40 produced inhibition of hindpaw reflex excitability at all stimulus intensities, with a similar pattern and degree as seen following previous hindpaw incision (n=4; fig. 4B). There was no main effect of prior incision site (F1,6=0.063, P=0.810) or stimulus intensity (F5,30=1.47, P=0.229)(two-way repeated measures ANOVA with incision group as between-subject and stimulus intensity as repeated within-subject variable). Thus, neonatal incision produces alterations in descending RVM modulation, with a generalized impact on spinal cord nociceptive processing that is not restricted to reflexes evoked from the previously injured paw.

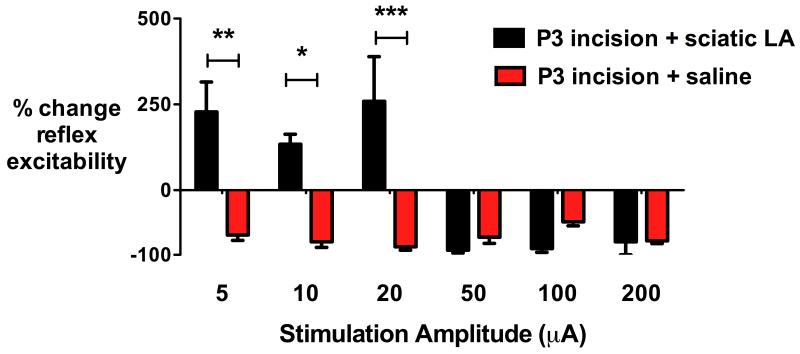

Sciatic nerve blockade at the time of neonatal incision prevents the change in RVM function

To evaluate the role of injury-induced primary afferent activity, P3 pups received peri-operative percutaneous perisciatic nerve injections of 40 μl 0.5% levobupivacaine or saline, 15 min prior to incision and at 3×2 h intervals. Effective local anesthetic sciatic block was confirmed by ipsilateral motor block and loss of withdrawal reflex response to a suprathreshold mechanical stimulus (vFh 14; 13g), with resolution of motor block and partial recovery from sensory block prior to each subsequent block. When neonatal incision was performed with perioperative sciatic nerve block (n=5), electrical stimulation of the RVM produced the typical bimodal effect of facilitation at low intensities (5-20 μA) and inhibition at higher intensities (50-200 μA). However, in littermate control animals given saline rather than local anesthetic injections (n=4), inhibition of hindlimb reflex excitability was produced across all RVM stimulus current intensities (fig. 5), again confirming the impact of neonatal incision seen in figure 2. Comparison of levobupivacaine and saline groups revealed a main effect of treatment (F1,7=7.606, P=0.028) and stimulus intensity (F5,35=6.542 P<0.001; two way repeated measures ANOVA with incision group and stimulus intensity as variables). Significant differences were seen at low stimulus amplitudes (5 μA, 10 μA and 20 μA; P<0.05-0.001; two way repeated measures ANOVA with Bonferroni post-hoc comparisons; fig. 5) following neonatal incision, with facilitation in the levobupivacaine group but inhibition in the saline group. Neonatal perioperative sciatic nerve blockade normalized the reflex response to RVM stimulation in adulthood. Comparison of the P3 incision plus perioperative local anaesthetic group (n=5) and adult uninjured controls (n=5, as shown in fig. 2) found no main effect of treatment group (F1,8=1.89. P=0.21), and although the bimodal pattern was associated with an overall main effect of stimulus intensity (F5,40=10.1 P<0.001), values at each given intensity did not differ between the naïve group and the incision with sciatic block group (two-way repeated measures ANOVA with incision group and stimulus intensity as variables followed by Bonferroni post-hoc comparisons).

Fig. 5.

Perioperative sciatic nerve block prevents injury-induced changes in rostroventral medulla (RVM) modulation in adulthood. Prior plantar incision was performed at postnatal day (P)3 with perioperative (15 min pre-incision and at 3×2 h intervals) percutaneous sciatic nerve injections of local anesthetic (LA; 40 μl 0.5% levobupivacaine) (P3 incision + sciatic LA, n=5) or saline (P3 incision + saline, n=4). At P40, spinal reflex excitability (quantified as the percentage change from baseline in the area under the mechanical stimulus vs electromyography response relationship) was compared during electrical stimulation of the RVM. Following incision with sciatic block the typical adult response is seen at P40, with facilitation at low intensity (5, 10 and 20 μA) and inhibition at high intensity (50, 100 and 200 μA) RVM stimulation. In the incision with saline group, all intensities of RVM stimulation inhibited reflex excitability. Bars = mean±SEM, *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001 two-way repeated measures ANOVA with treatment as between-subject and stimulus intensity as repeated within-subject variable followed by Bonferrroni post-hoc comparisons.

Discussion

Hindpaw incision in the neonatal rat dramatically alters the pattern of descending modulation from the RVM in adulthood. In animals with prior neonatal incision, spinal reflex excitability is inhibited by all intensities of RVM electrical stimulation, whereas uninjured littermates show the bimodal pattern typical of normal adult processing, with facilitation at low intensities and inhibition at high intensities. Neonatal surgical incision alters the developmental trajectory of behavioral sensory thresholds with delayed onset and a generalized distribution of hypoalgesia consistent with changes in supraspinal modulation. Similarly, enhanced inhibitory modulation from the RVM was not restricted to reflex responses from the previously injured area, but was also induced by prior injury of the contralateral hindpaw or forepaw. Finally, initiation of long-term alterations in RVM modulation was dependent on primary afferent activity at the time of neonatal injury, as pre- and post-incision sciatic nerve blockade resulted in RVM descending control developing normally. This work sheds important new light upon the long-term alterations in sensory processing following neonatal surgical injury and further emphasizes the importance of supraspinal centers in the control of spinal excitability.

Quantitative sensory testing in children 10-14 years following neonatal intensive care has demonstrated generalized decreases in thermal sensitivity,4,8 and the greater degree of change in those requiring neonatal surgery suggests an association with the severity of pain and/or degree of tissue injury.7 Here we used plantar hindpaw incision to model neonatal surgical injury, and showed an altered developmental trajectory of sensory thresholds with delayed emergence of behavioral threshold change in both the previously injured and contralateral hindpaw. The generalized distribution of sensory hypoalgesia following neonatal inflammation in the first postnatal week9 or P3 plantar incision12 suggests altered signaling from the brainstem.22 While this study does not directly demonstrate a causal relationship between increased descending inhibition from the RVM and sensory hypoalgesia following neonatal injury, the results support this hypothesis. In naïve rats, excitotoxic RVM lesions decrease behavioral mechanical sensory thresholds, suggesting that there is normally a baseline tonic inhibition from this region13 and it is possible that such lesions would produce even greater changes in sensory thresholds in adults with prior incision. However, our aim here was to perform a quantitative analysis of the direct effects of RVM stimulation and to test for neonatal incision-induced changes in the pattern of facilitatory and inhibitory modulation of nociceptive reflexes by descending RVM pathways. Increased RVM-mediated inhibition has previously been reported following neonatal inflammation as RVM electrical stimulation at P48 increased thermal withdrawal latency in the previously injured hindpaw, contralateral hindpaw and tail.23 However, changes were not consistently demonstrated at all stimulus intensities. Using quantitative electromyographic measurement of reflex sensitivity, we identified increased RVM mediated inhibition across all stimulus intensities at P40.

In adults, the RVM controls spinal excitability via populations of spinally projecting neurons from the nucleus raphe magnus and surrounding paragigantocellualris, leading to descending inhibitory or facilitatory modulation depending on the intensity of stimulation.24-27 This bidirectional control is mediated by pain facilitating ON cells and pain inhibiting OFF cells whose activity are linked with the initiation of spinal mediated reflex withdrawal.28-30 The RVM is an output nucleus for other more rostral centers particularly the periaqueductal grey (PAG), which in turn integrates information from forebrain regions. For some time it was thought that supraspinal sites played little role in the spinal processing of pain in early life. Descending inhibitory mechanisms are late to mature; electrical stimulation of descending axons in the dorsolateral funiculus did not inhibit dorsal horn cell activity31 and electrical stimulation of the PAG did not prolong thermal tail flick latency32 until P21, and in both cases responses were initially weaker than in adults. More recently it has become clear that the RVM can modulate excitability in the developing spinal cord, but that the dominant effect is facilitation13 that is focussed upon A-fibre rather than C-fibre evoked activity in the dorsal horn.15 The onset of biphasic inhibitory and facilitatory responses takes place during a critical period in the fourth postnatal week.14 In this study we have shown that neonatal surgical incision of the hindpaw significantly perturbs normal RVM development, resulting in enhanced descending inhibition of spinal nociceptive processing in early adulthood.

Consistent with clinical reports of generalized changes in sensory threshold following neonatal surgery,7 the changes in RVM modulation reported here are not somatotopically directed. Neonatal incision produces generalized changes in baseline sensitivity that are not restricted to the previously injured paw, and alterations in RVM modulation of spinal reflex excitability are evident if neonatal incision had been performed in the same paw, contralateral hindpaw, or forepaw. Most brainstem neuronal groups projecting to the cervical and lumbosacral spinal cord are distributed bilaterally and there is a lack of distinct somatotopy.33 RVM neurons also project to different spinal levels with axonal projections that overlap and terminate in the grey matter of multiple segments throughout the cord.34 Within the RVM itself, axons of all classes of cells collateralize. This arrangement may differ early in life, or neonatal injury may change the arrangement of terminations within the dorsal horn, but this requires further investigation.

Our results suggest a failure of maturation of excitatory circuitry or an enhancement of inhibitory circuitry, or both, within the RVM following neonatal incision. Underlying mechanisms require further investigation. Brainstem raphe serotonergic neurons, which play an important role in descending pain control, are very excitable and lack GABAergic and 5-HT1A autoreceptor mediated inhibition before P21, making them highly susceptible to external early life stressors.35 Our data show that the barrage of nociceptor action potential activity triggered by paw incision is an essential step in evoking the change in RVM descending control. Balanced peripheral neural activity is required for normal maturation of central nociceptive circuits in the spinal cord36,37 and this may in turn reflect upon the maturation of RVM spinal projections. Neonatal incision produces specific age-dependent changes in synaptic signaling in the spinal cord,38,39 and changes in glutamatergic signaling are prevented by prolonged sciatic nerve blockade with tetrodotoxin or bupivacaine hydroxide.40 Although a single preoperative sciatic nerve block reduces hyperalgesia 24 h following plantar incision in rat pups,10,41 additional blocks were required to prevent the enhanced spinal reflex and behavioral response to subsequent incision.10 This suggests that maintaining blockade through the initial perioperative period is required to minimize the long-term impact of neonatal incision. The relatively short duration of local anesthetic sciatic block in neonatal animals,17 necessitates repeat injection but this does not produce histological changes in the nerve.10 We now show that the same protocol also prevents the long-term changes in RVM signaling following neonatal incision, indicating specific activity-dependent effects that are independent of systemic effects such as stress or maternal separation. Neonatal injury has been associated with a range of behavioral outcomes and alterations in stress responsivity in adulthood.42-44 In the current experiments, control animals had the same degree of handling, maternal separation and brief anesthesia during the neonatal period, and sciatic block controls had additional interventions with repeated injections of saline, but RVM responses did not differ from age-matched naïve groups.

The clinical implications of altered descending modulation are less apparent than the enhanced segmental response to repeat injury. Generalized hypoalgesia may be considered a compensatory response to early life pain and reduced sensitivity to common bumps and scrapes has been reported in childhood.45 However, responses change with age and are also influenced by parental response and child coping style.8 This complexity is reflected by functional magnetic resonance imaging in preterm children aged 11-16 years which demonstrated increased activation in response to a noxious heat stimulus in multiple brain regions related to sensory, affective and cognitive aspects of pain. Alterations were also found in the PAG which may have implications for descending modulation from the brainstem,3 but the impact of neonatal pain experience on descending modulatory pathways has not been extensively evaluated. Conditioned pain modulation with reductions in perceived pain intensity following a conditioning stimulus at a distant body site (e.g., cold pressor test) are thought to reflect descending inhibition.46 Alterations in dynamic inhibition have been identified in preterm children aged 7-11 years, with enhanced inhibition in a low-pain preterm group but a lack of inhibition in a high-pain preterm group.47 However as the sample size was small, and the efficacy of conditioned pain modulation may be influenced by sex48 and age throughout childhood and adolescence,49 further evaluation is warranted.

In conclusion, it is increasingly apparent that early life injury produces developmentally regulated effects on sensory and nociceptive processing that are not seen following the same injury at older ages. However, different mechanisms at multiple points in nociceptive pathways may be involved, and overall functional effects emerge at different ages. Here we show that neonatal surgical injury alters the maturation of the RVM and supraspinal control of spinal excitability. The time course and distribution of behavioral hypoalgesia, and the altered responses to RVM stimulation, confirm increased descending inhibitory effects that are consistent with the altered sensory processing in preterm children following neonatal intensive care and surgery. These findings emphasize the sensitivity of the developing nervous system to alterations in neural activity produced by pain and injury, and highlight the importance of adequate perioperative analgesia when surgery is required in the neonatal period.

What we already know about this topic

Sensory transmission and processing in the spinal cord is modulated by descending influences from the rostroventral medulla (RVM)

Although neonatal pain and injury is known to alter sensory thresholds later in life in animals, the role of the RVM in this plasticity is unknown

What this article tells us that is new

In rats, neonatal incisional surgery to the paw resulted in reduced sensitivity to mechanical or thermal stimuli in adulthood and changed the effect of RVM stimulation from a bimodal facilitation and inhibition, to only inhibition

Regional anesthesia at the time of neonatal surgery prevented these changes in adulthood

Acknowledgments

Disclosure of funding received

This work was funded by Medical Research Council Grant MR/K022636/1, London, United Kingdom (SMW); Medical Research Council Grant G0901269, London, United Kingdom (MF); and Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council Grant BBI001565/1, Swindon, United Kingdom (GJH). Dr Walker is also supported by the Great Ormond Street Hospital Children’s Charity, London, United Kingdom.

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing interests.

References

- 1.Fitzgerald M, Walker SM. Infant pain management: A developmental neurobiological approach. Nat Clin Pract Neurol. 2009;5:35–50. doi: 10.1038/ncpneuro0984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Walker SM. Biological and neurodevelopmental implications of neonatal pain. Clin Perinatol. 2013;40:471–91. doi: 10.1016/j.clp.2013.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hohmeister J, Kroll A, Wollgarten-Hadamek I, Zohsel K, Demirakca S, Flor H, Hermann C. Cerebral processing of pain in school-aged children with neonatal nociceptive input: An exploratory fMRI study. Pain. 2010;150:257–67. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2010.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hermann C, Hohmeister J, Demirakca S, Zohsel K, Flor H. Long-term alteration of pain sensitivity in school-aged children with early pain experiences. Pain. 2006;125:278–85. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2006.08.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Buskila D, Neumann L, Zmora E, Feldman M, Bolotin A, Press J. Pain sensitivity in prematurely born adolescents. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2003;157:1079–82. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.157.11.1079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schmelzle-Lubiecki BM, Campbell KA, Howard RH, Franck L, Fitzgerald M. Long-term consequences of early infant injury and trauma upon somatosensory processing. Eur J Pain. 2007;11:799–809. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpain.2006.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Walker SM, Franck LS, Fitzgerald M, Myles J, Stocks J, Marlow N. Long-term impact of neonatal intensive care and surgery on somatosensory perception in children born extremely preterm. Pain. 2009;141:79–87. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2008.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hohmeister J, Demirakca S, Zohsel K, Flor H, Hermann C. Responses to pain in school-aged children with experience in a neonatal intensive care unit: Cognitive aspects and maternal influences. Eur J Pain. 2009;13:94–101. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpain.2008.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ren K, Anseloni V, Zou SP, Wade EB, Novikova SI, Ennis M, Traub RJ, Gold MS, Dubner R, Lidow MS. Characterization of basal and re-inflammation-associated long-term alteration in pain responsivity following short-lasting neonatal local inflammatory insult. Pain. 2004;110:588–96. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2004.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Walker SM, Tochiki KK, Fitzgerald M. Hindpaw incision in early life increases the hyperalgesic response to repeat surgical injury: Critical period and dependence on initial afferent activity. Pain. 2009;147:99–106. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2009.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chu YC, Chan KH, Tsou MY, Lin SM, Hsieh YC, Tao YX. Mechanical pain hypersensitivity after incisional surgery is enhanced in rats subjected to neonatal peripheral inflammation: Effects of N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor antagonists. Anesthesiology. 2007;106:1204–12. doi: 10.1097/01.anes.0000267604.40258.d1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Beggs S, Currie G, Salter MW, Fitzgerald M, Walker SM. Priming of adult pain responses by neonatal pain experience: Maintenance by central neuroimmune activity. Brain. 2012;135:404–17. doi: 10.1093/brain/awr288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hathway GJ, Koch S, Low L, Fitzgerald M. The changing balance of brainstem-spinal cord modulation of pain processing over the first weeks of rat postnatal life. J Physiol. 2009;587:2927–35. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2008.168013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hathway GJ, Vega-Avelaira D, Fitzgerald M. A critical period in the supraspinal control of pain: Opioid-dependent changes in brainstem rostroventral medulla function in preadolescence. Pain. 2012;153:775–83. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2011.11.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Koch SC, Fitzgerald M. The selectivity of rostroventral medulla descending control of spinal sensory inputs shifts postnatally from A-fibre to C-fibre evoked activity. J Physiol. 2014;592:1535–44. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2013.267518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brennan TJ, Vandermeulen EP, Gebhart GF. Characterization of a rat model of incisional pain. Pain. 1996;64:493–501. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(95)01441-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hu D, Hu R, Berde CB. Neurologic evaluation of infant and adult rats before and after sciatic nerve blockade. Anesthesiology. 1997;86:957–65. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199704000-00026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Walker SM, Westin BD, Deumens R, Grafe M, Yaksh TL. Effects of intrathecal ketamine in the neonatal rat: Evaluation of apoptosis and long-term functional outcome. Anesthesiology. 2010;113:147–59. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e3181dcd71c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dirig DM, Salami A, Rathbun ML, Ozaki GT, Yaksh TL. Characterization of variables defining hindpaw withdrawal latency evoked by radiant thermal stimuli. J Neurosci Methods. 1997;76:183–91. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0270(97)00097-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kwok CH, Devonshire IM, Bennett AJ, Hathway GJ. Postnatal maturation of endogenous opioid systems within the periaqueductal grey and spinal dorsal horn of the rat. Pain. 2014;155:168–78. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2013.09.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Walker SM, Meredith-Middleton J, Cooke-Yarborough C, Fitzgerald M. Neonatal inflammation and primary afferent terminal plasticity in the rat dorsal horn. Pain. 2003;105:185–95. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(03)00201-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang G, Ji Y, Lidow MS, Traub RJ. Neonatal hind paw injury alters processing of visceral and somatic nociceptive stimuli in the adult rat. J Pain. 2004;5:440–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2004.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhang YH, Wang XM, Ennis M. Effects of neonatal inflammation on descending modulation from the rostroventromedial medulla. Brain Res Bull. 2010;83:16–22. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresbull.2010.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhuo M, Gebhart GF. Biphasic modulation of spinal nociceptive transmission from the medullary raphe nuclei in the rat. J Neurophysiol. 1997;78:746–58. doi: 10.1152/jn.1997.78.2.746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fields HL, Basbaum AI, Clanton CH, Anderson SD. Nucleus raphe magnus inhibition of spinal cord dorsal horn neurons. Brain Res. 1977;126:441–53. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(77)90596-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fields HL, Basbaum AI. Brainstem control of spinal pain-transmission neurons. Annu Rev Physiol. 1978;40:217–48. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ph.40.030178.001245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fields HL, Anderson SD. Evidence that raphe-spinal neurons mediate opiate and midbrain stimulation-produced analgesias. Pain. 1978;5:333–49. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(78)90002-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Heinricher MM, Barbaro NM, Fields HL. Putative nociceptive modulating neurons in the rostral ventromedial medulla of the rat: Firing of on- and off-cells is related to nociceptive responsiveness. Somatosens Mot Res. 1989;6:427–39. doi: 10.3109/08990228909144685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fields HL, Bry J, Hentall I, Zorman G. The activity of neurons in the rostral medulla of the rat during withdrawal from noxious heat. J Neurosci. 1983;3:2545–52. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.03-12-02545.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fields HL, Vanegas H, Hentall ID, Zorman G. Evidence that disinhibition of brain stem neurones contributes to morphine analgesia. Nature. 1983;306:684–6. doi: 10.1038/306684a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fitzgerald M, Koltzenburg M. The functional development of descending inhibitory pathways in the dorsolateral funiculus of the newborn rat spinal cord. Brain Res. 1986;389:261–70. doi: 10.1016/0165-3806(86)90194-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.van Praag H, Frenk H. The development of stimulation-produced analgesia (SPA) in the rat. Brain Res Dev Brain Res. 1991;64:71–6. doi: 10.1016/0165-3806(91)90210-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Leong SK, Shieh JY, Wong WC. Localizing spinal-cord-projecting neurons in neonatal and immature albino rats. J Comp Neurol. 1984;228:18–23. doi: 10.1002/cne.902280104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Huisman AM, Kuypers HG, Verburgh CA. Quantitative differences in collateralization of the descending spinal pathways from red nucleus and other brain stem cell groups in rat as demonstrated with the multiple fluorescent retrograde tracer technique. Brain Res. 1981;209:271–86. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(81)90153-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rood BD, Calizo LH, Piel D, Spangler ZP, Campbell K, Beck SG. Dorsal raphe serotonin neurons in mice: Immature hyperexcitability transitions to adult state during first three postnatal weeks suggesting sensitive period for environmental perturbation. J Neurosci. 2014;34:4809–21. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1498-13.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Koch SC, Tochiki KK, Hirschberg S, Fitzgerald M. C-fiber activity-dependent maturation of glycinergic inhibition in the spinal dorsal horn of the postnatal rat. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:12201–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1118960109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Waldenstrom A, Thelin J, Thimansson E, Levinsson A, Schouenborg J. Developmental learning in a pain-related system: Evidence for a cross-modality mechanism. J Neurosci. 2003;23:7719–25. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-20-07719.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Li J, Baccei ML. Neonatal tissue damage facilitates nociceptive synaptic input to the developing superficial dorsal horn via NGF-dependent mechanisms. Pain. 2011;152:1846–55. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2011.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Li J, Blankenship ML, Baccei ML. Deficits in glycinergic inhibition within adult spinal nociceptive circuits after neonatal tissue damage. Pain. 2013;154:1129–39. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2013.03.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Li J, Walker SM, Fitzgerald M, Baccei ML. Activity-dependent modulation of glutamatergic signaling in the developing rat dorsal horn by early tissue injury. J Neurophysiol. 2009;102:2208–19. doi: 10.1152/jn.00520.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ririe DG, Barclay D, Prout H, Tong C, Tobin JR, Eisenach JC. Preoperative sciatic nerve block decreases mechanical allodynia more in young rats: Is preemptive analgesia developmentally modulated? Anesth Analg. 2004;99:140–5. doi: 10.1213/01.ANE.0000114181.69204.72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schwaller F, Fitzgerald M. The consequences of pain in early life: Injury-induced plasticity in developing pain pathways. Eur J Neurosci. 2014;39:344–52. doi: 10.1111/ejn.12414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Victoria NC, Inoue K, Young LJ, Murphy AZ. Long-term dysregulation of brain corticotrophin and glucocorticoid receptors and stress reactivity by single early-life pain experience in male and female rats. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2013;38:3015–28. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2013.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Victoria NC, Inoue K, Young LJ, Murphy AZ. A single neonatal injury induces life-long deficits in response to stress. Dev Neurosci. 2013;35:326–37. doi: 10.1159/000351121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Grunau RV, Whitfield MF, Petrie JH. Pain sensitivity and temperament in extremely low-birth-weight premature toddlers and preterm and full-term controls. Pain. 1994;58:341–6. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(94)90128-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pud D, Granovsky Y, Yarnitsky D. The methodology of experimentally induced diffuse noxious inhibitory control (DNIC)-like effect in humans. Pain. 2009;144:16–9. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2009.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Goffaux P, Lafrenaye S, Morin M, Patural H, Demers G, Marchand S. Preterm births: Can neonatal pain alter the development of endogenous gating systems? Eur J Pain. 2008;12:945–51. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpain.2008.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Evans S, Seidman LC, Lung KC, Zeltzer LK, Tsao JC. Sex differences in the relationship between maternal fear of pain and children’s conditioned pain modulation. J Pain Res. 2013;6:231–8. doi: 10.2147/JPR.S43172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tsao JC, Seidman LC, Evans S, Lung KC, Zeltzer LK, Naliboff BD. Conditioned pain modulation in children and adolescents: Effects of sex and age. J Pain. 2013;14:558–67. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2013.01.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]