Abstract

Background and Aims

Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease is a common cause of chronic liver disease. Celiac disease alters intestinal permeability and treatment with a gluten-free diet often causes weight gain, but so far there are few reports of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in patients with celiac disease.

Methods

Population-based cohort study. We compared the risk of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease diagnosed from 1997-2009 in individuals with celiac disease (n=26,816) to matched reference individuals (n=130,051). Patients with any liver disease prior to celiac disease were excluded, as were individuals with a lifetime diagnosis of alcohol-related disorder to minimize misclassification of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Cox regression estimated hazard ratios for nonalcoholic fatty liver disease were determined.

Results

During 246,559 person-years of follow-up, 53 individuals with celiac disease had a diagnosis of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (21/100,000 person-years). In comparison, we identified 85 reference individuals diagnosed with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease during 1,488,413 person-years (6/100,000 person-years). This corresponded to a hazard ratio of 2.8 (95%CI=2.0-3.8), with the highest risk estimates seen in children (HR=4.6; 95%CI=2.3-9.1). The risk increase in the first year after celiac disease diagnosis was 13.3 (95%CI=3.5-50.3) but remained significantly elevated even beyond 15 years after the diagnosis of celiac disease (HR=2.5; 95% CI 1.0-5.9).

Conclusion

Individuals with celiac disease are at increased risk of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease compared to the general population. Excess risks were highest in the first year after celiac disease diagnosis, but persisted through 15 years beyond diagnosis with celiac disease.

Keywords: Autoimmune, Steatohepatitis, Gluten, Nash, Nafld, Celiac disease

Introduction

Celiac disease (CD) is associated with both acute and chronic liver diseases, especially autoimmune liver disease.[1, 2] Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is the most common cause of chronic liver disease in children and adolescents in Western nations[3], is estimated to be present in 20% of the population[4], and may progress to fibrosis and cirrhosis in some.[4, 5] Yet, data establishing whether individuals w i th CD may be at risk of NAFLD are nascent.[1, 6] Metabolic risks as well as those altering intestinal permeability are potential triggers for NAFLD which may be found in CD.

Obesity and the metabolic syndrome are accepted as major accompaniments of NAFLD [7], though not all patients with NAFLD are obese.[8] A high-fat diet and sedentary lifestyle are alterable risks, modifications here can yield improvements in NAFLD [9], and recovery after weight loss may be related to reduced insulin resistance.[10] Many adults and children with CD are overweight or obese at diagnosis, or become overweight after treatment [11, 12], increasing risks for NAFLD. Children[13] and adults[14] with CD may have increased cardiovascular risks which overlap with those for NAFLD.

The gut-liver axis via the portal system has been implicated as a potential route of inflammatory cytokines, which may trigger the onset of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH). Levels of endotoxin (lipopolysaccharide), derived from intestinal gram-negative microbiota, are elevated in the sera of adults[15] and children[16] with NAFLD, suggesting increased intestinal permeability among these individuals. Small intestinal bacterial overgrowth (SIBO) is more common among patients with NAFLD than healthy individuals[17] and is associated with higher TNF-α levels, independent of increases in gut permeability markers.[18] Individuals with CD have altered intestinal permeability due to the disturbance of mucosal integrity induced by gluten and the associated inflammatory response.[19] Additionally, SIBO is common among individuals with CD[20], which may further impair mucosal barriers and may have other links to the pathogenesis of NAFLD.[18] Whether a compromised intestinal barrier is a cause or effect of NAFLD requires additional study, though the prevailing theory is that bacteria-derived endotoxin and related cytokines may serve as a “second hit” among certain patients with hepatic steatosis leading to development of NASH.[21]

In this population-based study, we aim to investigate the frequency with which NAFLD is identified among individuals with CD.

Materials and methods

Study participants

In 2006-2008 we collected small intestinal biopsy record data from all 28 pathology departments in Sweden. The biopsies had been performed in 1969-2008 and collected data included date of biopsy, biopsy site (duodenum or jejunum), morphology codes consistent with villous atrophy (VA, Marsh grade III) (see appendix), and personal identity number (PIN).[22] In this paper we equated VA with CD (details of the data collection have been published before).[23] While we did not require positive CD serology for a CD diagnosis, patient chart validation in a random subset of individuals with VA found 88% were positive for transglutaminase, endomysium or gliadin antibodies at the time of biopsy.[22]

We then matched each individual with CD with up to 5 reference individuals for age, sex, calendar year and county of residence at the time of biopsy. Reference individuals were sampled from the Swedish Total Population Registry maintained by the government agency Statistics Sweden. Through this matching procedure, for example, a woman born in 1963 with a CD diagnosis in 1998 living in the county Dalarna was matched to up to five other women, born in 1963, living in that county in 1998. After removal of duplicates and potential data irregularities, our remaining study participants (29,096 CD patients and 144,522 reference individuals) were identical to that of our mortality study in CD.[24]

NAFLD, other liver disease, and alcohol use

Patients with our outcome measure, NAFLD, were identified using a search for the ICD-10 (International Classification of Disease) code K76.0 in the Swedish Patient Registry, a registry of patient diagnoses initiated in 1964 which became nationwide in 1987. More than 99% of all somatic care is registered in the Registry and most disorders have a positive predictive value of 85-95%.[25] Prior to the year 2000, the Patient Registry only contained inpatient data, but since 2000 has included both inpatient and hospital-based outpatient data. We restricted our follow-up to 1997-2009 since the Swedish ICD-10 began in 1997 (before that, NAFLD could not be distinguished from other liver disease).

Initially, to rule out that CD had been diagnosed due to prior liver disease (e.g. misclassified NAFLD), we excluded individuals with any liver disorder diagnosed before a first intestinal biopsy with VA (n=948; 3.3%) or before the corresponding date in reference individuals (n=3217; 2.2%). Hence, all study participants were free of a diagnosis of liver disease at study entry.

Since alcohol is a predominant cause of fatty liver disease, we also identified all individuals with a lifetime diagnosis of alcohol-related disease (see appendix for relevant ICD codes) (CD: n=812, 2.8%; and reference individuals: n=3845; 2.7%). These ICD codes represent both somatic and psychiatric disorders where alcohol use has been implicated and did, in some circumstances, overlap with individuals who had a prior diagnosis of liver disease. Swedish national registries do not otherwise record alcohol use in healthy people. At this stage we also excluded study participants with a follow-up that ended before 1997 (CD: n=723 (2.5%); reference: n=2899 (2.1%)) since they could not potentially be diagnosed with fatty liver since that diagnosis was only introduced in 1997.

Finally, our analyses were carried out stratum-wise. We compared each CD individual only with his/her matched reference individuals and thereafter calculated a summary estimate for NAFLD, excluding reference individuals in strata where the CD individual had been excluded for any reason. The final dataset therefore consisted of 26,816 individuals with CD and 130,051 reference individuals (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of Study Participants.

| Matched Reference Individuals | Celiac Disease | |

|---|---|---|

| Total | 130,051 | 26,816 |

| Age at study entry (Y), N (%) | ||

| 0-19 | 57,029 (43.9) | 11,488 (42.8) |

| 20-39 | 24,478 (18.8) | 5,044 (18.7) |

| 40-59 | 27,984 (21.5) | 5,815 (21.7) |

| >60 | 20,560 (15.8) | 4,509 (16.8) |

| Entry year (median, range) | 1999, 1969-2008 | 1999, 1969-2008 |

| Follow-up, years (median, range) | 10, 0-41 | 10, 0-40 |

| Follow-up, years (mean ± SD) | 11.4 ± 6.4 | 11.4 ± 6.4 |

| Sex (%) | ||

| Females | 81,844 (62.9) | 16,761 (62.5) |

| Males | 48,207 (37.1) | 10,055 (37.5) |

| Nordic, N (%) | 122,480 (94.2) | 25,930 (96.7) |

| Calendar year | ||

| -1989 | 16,241 (12.6) | 3,481 (13.0) |

| 1990-99 | 53,407 (41.1) | 11,029 (41.1) |

| 2000- | 60,223 (46.3) | 12,306 (45.9) |

| Socioeconomic Status | ||

| ≤9 years of primary school | 34,457 (26.5) | 7,076 (26.4) |

| 2 years of high school | 27,138 (20.9) | 5,610 (20.9) |

| 3-4 years of high school | 27,112 (20.8) | 5,546 (20.7) |

| College/university | 38,655 (29.7) | 7,877 (29.4) |

| Missing | 2,689 (2.1) | 707 (2.6) |

| Censored before end of follow-up | ||

| Death | 8,416 (5.8) | 2,230 (7.7) |

| Emigration | 1,789 (1.2) | 205 (0.7) |

| Type 2 diabetes§ | 3,919 (3.0) | 818 (3.1) |

| Autoimmune thyroid disease§ | 2,140 (1.6) | 1,302 (4.9) |

| Drug use§ | ||

| Amiodarone | 139 (0.1) | 25 (0.1) |

| Corticosteroids | 12,836 (9.9) | 3,776 (14.1) |

| Methotrexate | 811 (0.6) | 262 (1.0) |

| Tamoxifen | 404 (0.3) | 67 (0.2) |

| Tetracycline | 17,487 (13.4) | 4,382 (16.3) |

| Lipid owering drugs | 12,028 (9.2) | 2,423 (9.0) |

Ages were rounded to the nearest year.

Follow-up time until diagnosis of NAFLD, death, emigration or December 31, 2009. In reference individuals follow-up also ended with small intestinal biopsy.

For definitions see main text and appendix.

Main covariates

The government agency Statistics Sweden delivered data on the following potential confounders: country of birth (Nordic vs. not Nordic), educational level, and socioeconomic status at the time of biopsy. When a child did not have data on socioeconomic status or education, parental data were used. Crude and adjusted risk estimates were limited to individuals with complete data on socioeconomic status and education (72.0% of CD patients and 72.5% of reference individuals had complete data on these covariates). We categorized education into 4 groups (≤9 years of primary school, 2 years of high school, 3-4 years of high school, college/university) while socioeconomic status was categorized into 6 groups (in accordance with the European Socioeconomic Classification, ESeC: levels 1, 2, 3+6, 7, 8, and 9). (For additional details see our previous paper.[26])

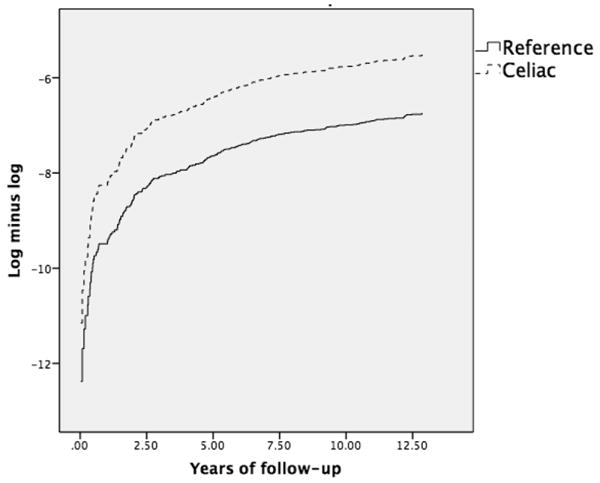

Statistics

Hazard ratios (HRs) for NAFLD were estimated using internally stratified Cox Regression, with all comparisons made within a stratum of matched individuals as in a conditional logistic regression. The proportional hazards assumption was tested using log-minus-log curves (Appendix). Although we found that the assumption of proportional hazards was not violated, we calculated follow-up specific HRs since the HR for NAFLD was substantially higher in the first year after CD diagnosis. We began follow-up on the date of 1st biopsy with VA (equivalent to CD in our study) and on the corresponding date in matched reference individuals or on Jan 1, 1997, whichever occurred latest. Follow-up time ended with NAFLD diagnosis, December 31, 2009, emigration, or death, whichever occurred first.

In pre-defined analyses, we calculated HRs for NAFLD in males-females, different age strata (e.g. <=19 years, see also Table 1), and calendar year (Table 1). Potential effect modification was tested by entering interaction terms in the statistical models. We also carried out separate analyses adjusting for country of birth, level of education, and socioeconomic status.

In a posthoc analysis, we also examined the risk of NAFLD in 11,121 CD patients with Marsh 1-2 lesions (inflammation but no villous atrophy). The data collection of these individuals has been described before[27] and was identical to that of CD, except that other SnoMed codes were used (see Appendix).

In a sensitivity analysis we tested if the association between CD and NAFLD changed using attained age instead of time since biopsy as the time scale. Finally, we examined if adjustment for a type 2 diabetes, autoimmune thyroid disease, lipid-lowering drugs (as proxy for dyslipidemia) or drugs linked to NAFLD would influence the association between CD and NAFLD. Drug treatment was identified using relevant ATC codes in the Swedish Prescribed Drug Registry (Appendix). Type 2 diabetes and autoimmune thyroid disease were identified according to relevant ICD-codes in the Swedish Patient Registry (Appendix). This latter registry started on July 1, 2005 and hence we restricted this last analysis to individuals who had not died or emigrated prior to this date.

Prior NAFLD and later CD

To investigate if a positive association with NAFLD was present before CD diagnosis, we performed a case-control study of 16,865 individuals with CD diagnosed in 1997 or later, and 83,767 matched controls. Data were analyzed using a conditional logistic regression model which eliminated the influence of the matching criteria (age, sex, birth year, and county). In a priori analyses we stratified for time between NAFLD and later CD (<1 year, 1-5 years and 6+ years).

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 22 (SPSS Statistics, Version 22.0, Armonk, NY). P-values <0.05 were considered to be statistically significant.

Ethics

This study was approved by the Regional Ethical Review Board in Stockholm (2006/633-31/4). Because this was a register-based study, no participant was contacted and all data were anonymised prior to data analyses.

Results

The median age at CD diagnosis was 28 years (for reference individuals: 27 years at study entry) (Table 1), with 42.8% diagnosed in childhood. Some 87% of CD individuals were diagnosed in 1990 or later (Table 1), and 97% were born in the Nordic countries (Table 1). The median follow-up was 10 years.

The median age at NAFLD diagnosis was 51 years in CD patients and 55 years in reference individuals. Among CD individuals with a NAFLD diagnosis, the median duration until NAFLD was 5.2 years after CD diagnosis (reference individuals: 6.6 years since study entry).

Risk of future NAFLD

During 246,559 years of follow-up, 53 individuals with CD had a diagnosis of NAFLD (21/100,000 person-years). In comparison, we identified 85 reference individuals with a NAFLD diagnosis during 1,488,413 person-years (6/100,000 person-years). This corresponded to a HR of 2.8 (95%CI=2.0-3.8; p<0.001). HRs did not change with adjustment for country of birth, socioeconomic status and level of education (adjusted HR= 2.8; 95%CI=2.0-3.9; p<0.001; Appendix).

The HRs differed by follow-up time with the highest risks immediately after CD diagnosis. CD was associated with a 4.2-fold increased risk of NAFLD in the first five years after diagnosis (Table 2). This excess risk was to a large extent due to NAFLD diagnosed in the first year after CD diagnosis (HR for NAFLD=13.3; 95%CI=3.5-50.3). Of 25 individuals with CD who had a diagnosis of NAFLD in the first five years after diagnosis, 8 were diagnosed within the first year after biopsy (compared to 9/66 reference individuals who had a diagnosis of NAFLD in the first five years after study entry). Excluding the first year of follow-up, the HR for NAFLD diagnosis for those with CD was 2.5 (95%CI=1.8-3.7). The HR for NAFLD more than 15 years after CD diagnosis was also 2.5 (95%CI=1.0-5.9; p=0.043). When we restricted our data to individuals entering the study on Jan 1, 1997 or later, the HR for NAFLD was 3.6 (95%CI=2.3-5.6).

Table 2.

Relative risk of NAFLD based on follow-up time in individuals with celiac disease.

| Follow-up After CD Diagnosis (Years) |

CD: Observed Events |

CD: Expected Events |

HR; 95% CI | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| <1 | 8 | <1 | 13.3; 3.5-50.3 | <0.001 |

| <5 | 25 | 6 | 4.2; 2.5-7.2 | <0.001 |

| 5-9.99 | 9 | 7 | 1.3; 0.6-2.8 | 0.459 |

| 10-14.99 | 11 | 2 | 4.6; 2.0-10.6 | <0.001 |

| >15 | 8 | 3 | 2.5; 1.0-5.9 | 0.043 |

HR, Hazard ratio; CI, Confidence interval.

Reference is general population comparator cohort

Overall HRs for NAFLD were higher in males (4.5; 95%CI=2.7-7.6) than in females (2.1; 95%CI=1.3-3.2) (Table 3), but the difference did not reach statistical significance (p for interaction=0.126).The relative risk of NAFLD also seemed higher in individuals diagnosed with CD in childhood (4.6; 95%CI=2.3-9.1) compared to a 2-fold increased risk among individuals with a CD diagnosis from age 40 years or later, but neither here did the difference attain statistical significance (p for interaction with age at CD diagnosis was 0.059). Risk estimates were independent of calendar period (p for interaction=0.317). The HR for NAFLD in individuals diagnosed with CD in the latest calendar period (2000-2008) was 4.1 (95%CI=2.4-7.0).

Table 3.

Relative risk of NAFLD in relation to characteristics of patients with celiac disease.

| Subgroup | CD: Observed Events |

CD: Expected Events |

HR; 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | |||

| Males | 25 | 6 | 4.5; 2.7-7.6 |

| Females | 28 | 13 | 2.1; 1.3-3.2 |

| Age (Y) | |||

| <20 | 15 | 3 | 4.6; 2.3-9.1 |

| 20-39 | 14 | 4 | 3.7; 1.9-7.1 |

| 40-59 | 15 | 7 | 2.0; 1.1-3.6 |

| 60+ | 9 | 4 | 2.1; 1.0-4.5 |

| Calendar Period | |||

| -1989 | 7 | 3 | 2.3; 0.9-5.6 |

| 1990-1999 | 25 | 11 | 2.3; 1.4-3.6 |

| 2000-2008 | 21 | 5 | 4.1; 2.4-7.0 |

HR, Hazard ratio; CI, Confidence interval.

Reference is general population comparator cohort

Sensitivity analyses

Using attained age as the time scale did not influence our risk estimate (HR for NAFLD=2.8; 95% CI=2.0-3.9). Adjusting for type 2 diabetes, autoimmune thyroid disease, lipid treatment and other drugs previously linked to NAFLD did not influence the risk estimate (adjusted (HR=2.7; 95%CI=1.8-4.0).

Prior NAFLD and Later CD

Forty-seven individuals with CD (0.3%) and 46 matched controls (0.1%) had a diagnosis of NAFLD before the first biopsy showing CD, or before study entry for controls. This corresponded to an OR of 3.9 (95%CI=2.8-5.5; p<0.001). Adjustment for education, socioeconomic status and country of birth did not influence the risk estimate (adjusted HR=3.8; 95%CI=2.7-5.4). The positive association was to a large part explained by an 8.6-fold increased risk of CD in the first year following NAFLD diagnosis (95%CI=5.5-13.3), followed by a moderate increase thereafter (OR 1.6; 95%CI=0.9-3.1). There were insufficient cases of CD diagnosed more than 5 years after NAFLD diagnosis to calculate a meaningful risk estimate (95%CI=0.0-362).

Alcohol-related Liver Disease in Those With and Without CD

In a post hoc analysis, where we included individuals with alcohol-related diagnoses (otherwise excluded in all analyses to minimize misclassification of NAFLD), we examined the proportion of individuals with fatty liver who also had an alcohol-related liver disease. In CD patients with NAFLD, 12% (10/82) had an alcohol-related liver disease vs. 15% (18/121) of controls with NAFLD.

Additional Posthoc Analyses

Marsh 1-2 CD was also associated with an increased risk of NAFLD (HR=4.7; 95%CI=3.2-6.8).

Discussion

This nationwide study of more than 26,000 patients with CD found an increased risk of NAFLD in both children and adults with CD. The relative risk was highly increased in the first year of follow-up, but remained statistically significant even 15 years after CD diagnosis. In addition, those with a prior diagnosis of NAFLD appear to be at increased risk for a later diagnosis of CD. The prominent relative risk in the early years after diagnosis suggests a surveillance bias. This is not unexpected because one disease diagnosis or evaluation may lead to detection of the second disease.

NAFLD Risks in CD

NAFLD has been predominantly linked to obesity[5, 28], hyperlipidemia[5, 28], and insulin resistance[5], though NAFLD can occur in those with a normal body mass index (BMI).[8] The prevalence of CD among patients with NAFLD has been reported as 2.2-7.9%[29, 30] and among these patients BMI was often in the normal range.[29] Conversely, little is known of the risks of NAFLD in those already diagnosed with CD. The observed increased incidence of NAFLD in our study population is interesting in that it suggests increased metabolic risks in CD patients occurring with treatment or the involvement of other non-metabolic mechanisms for the onset of NAFLD.

Dyslipidemia requiring pharmacotherapy and type 2 diabetes did not appear to contribute to NAFLD risk in this study. Individuals with CD appear to have a decreased risk of type 2 diabetes even when controlling for BMI.[31] However, serum lipids may increase following treatment for CD.

The precise pathogenesis of NAFLD in CD is unclear. Some have speculated that cellular stress induced in CD patients may trigger the onset of NAFLD.[32] Intestinal permeability is increased in CD[33] as well as in NAFLD[17, 34], and SIBO, known to be increased both in CD[20] as well as in NAFLD[17, 18], may alter intestinal permeability.[35] Furthermore, increased intestinal permeability has been suggested as a potential trigger for the development of NASH in patients with hepatic steatosis. TNF-α, which mediates injury in CD and is increased in individuals with NASH[18], is believed to mediate the effects of endotoxin[36], potentially causing injury in those with nonalcoholic fatty liver to induce NASH. Clarifying the relationship between NAFLD and CD is important in that it identifies a potentially avoidable and treatable cause of liver disease among individuals with CD.

Strengths and Limitations

The major strength of this study is the large number of patients with CD (n=26,816) and the population-based nature of the study. In contrast with some older studies on comorbidities in CD[14], we did not rely on inpatient data to identify our exposure variable (CD). This is important since inpatient care is not routine for the diagnosis of CD, and our earlier research has shown that complications are more frequent in individuals hospitalized with their CD than in those identified through biopsy record data (for instance the HR for tuberculosis was 3.7 in inpatients with CD[37] compared with 2.0 in CD patients identified through biopsy records[38]). We used biopsy reports from all of Sweden's pathology departments to identify CD. This should have a high sensitivity for diagnosed CD (during the study time, 96-100% of all adult gastroenterologists and pediatricians report performing a biopsy before assigning a diagnosis of CD to the patient).[39]

Biopsy report data on morphology were based on a mean of 3 tissue specimens[23], and this should identify approximately 95% of all CD. VA also has a high positive predictive value (also 95%) for CD in a Swedish setting[39]. Although we are unaware of any study examining the validity of NAFLD in the Swedish Patient Registry, Carsjö et al have earlier found that 87% of individuals with a recorded diagnosis of chronic liver disease or liver cirrhosis in 1986 had a correct diagnosis, and 88% in patients diagnosed in 1990.[40]

In addition to the large number of study participants, another strength is the long follow-up. These two factors allowed us to calculate risk estimates for NAFLD even 15 years after CD diagnosis, and to perform important subgroup analyses.

We acknowledge a number of weaknesses. We cannot rule out that a number of reference individuals have undiagnosed CD. This is however unlikely to influence our HRs since the overall prevalence of CD in Sweden is 1-2 %[41], and less than 1 in 50 reference individuals should then have CD. If any, such misclassification is likely to decrease our HR for NAFLD somewhat and cannot explain the positive association seen in our study. Additionally, we acknowledge that the Patient Registry may have missed cases of NAFLD. One approach to increase the sensitivity for NAFLD would have been to identify individuals with unexplained chronic liver enzyme elevation accompanied by metabolic features. Unfortunately the Swedish ICD-10 system does not allow for this.

Given that the diagnosis code for NAFLD was not issued prior to 1997, there may be an underestimation of the early risk of NAFLD in individuals with CD diagnosed before this time. However, this would not diminish the early risk seen in those diagnosed in later years. Additionally, the follow-up strata used in our statistical design ensured that those diagnosed with NAFLD in 1998 (once the ICD-10 code K76.0 came into use) contributed to the risk increase in the follow-up stratum from 1982-1998, potentially leading to a minimal increase in risk estimates of development of NAFLD later after CD diagnosis, but would not have falsely increased risk estimates of NAFLD in the early years following CD diagnosis.

While overweight and obesity are common in CD, Swedish registers do not contain individual-based data on BMI. Nor is obesity generally recorded in the Patient Registry. In general, CD patients have a lower BMI before CD diagnosis than after[42], but we cannot rule out that adjustment for BMI would have influenced our risk estimates. We tried to minimize misclassification of NAFLD through excluding patients with a diagnosis of alcohol-related disease. Unfortunately Swedish national registries lack data on individual alcohol consumption and we were therefore unable to confirm that individuals classified as having NAFLD did in fact not have an alcohol consumption > 20-30g/day[43]. While this is a major shortcoming of our study, Sweden has a low per capita alcohol consumption[44] and NAFLD is generally much more common than alcohol-related fatty liver disease. Given that alcohol consumption is not regarded as positively associated with CD, the kind of misclassification that may occur in this study (NAFLD that is in fact alcohol-related) is therefore most likely to dilute associations and will not explain the positive association between CD and NAFLD seen in our study. Nevertheless, this is a major shortcoming of our study and while we may infer that the potential for such misclassification had no bearing upon our findings, this cannot be said for certain.

Finally, our measure of NAFLD (inpatient or hospital-based outpatient diagnosis) may have a low sensitivity of NAFLD. Many patients with NAFLD are unaware of their condition and do not seek healthcare. This may lead to an underestimate of NAFLD in our cohort. In addition, given the large-scale nature of this study, it is impossible to confirm how individual diagnoses of NAFLD were rendered, or if these diagnoses were appropriately assigned. Additionally, we were unable to examine the association between CD and undiagnosed NAFLD. Neither were we able to examine NAFLD appearance according to Marsh stages since the Swedish National Registries do not contain any data on histopathology.

Lastly, surveillance bias may have influenced our findings. Individuals with CD were likely followed more carefully than those in the general population, and this may have increased NAFLD diagnoses in CD patients. However, even prior to diagnosis with CD, the odds of a NAFLD diagnosis were significantly greater (OR 3.9) among those with a later diagnosis of CD versus those without a CD diagnosis. Whether this is due in part to evaluation of the patients' compliance prior to the CD diagnosis cannot be determined. However, these limitations are inherent in such a large-scale study.

Mechanisms

Of importance, the risk of NAFLD was also increased among individuals with Marsh 1-2 histology. Although these are results of a posthoc analysis, the findings are nevertheless intriguing. While many individuals with true CD do show Marsh 1-2 lesions, Marsh 1-2 may also reflect many non-CD conditions.[45] Among potential explanations are lack of treatment with a gluten-free diet (in a patient chart validation we have previously found that only 2/39 (5%) randomly selected individuals with Marsh 1-2 had been advised to adhere to a gluten-free diet[27]), that Marsh 1-2 represent other forms of inflammation/autoimmunity with even stronger links to NAFLD than CD, and surveillance bias or confounding by indication. Finally patients with Marsh 1-2 may share common risk factors with NAFLD.

We cannot rule out that some small intestinal biopsies in our study were carried out due to unrecorded liver disease prior to CD. Against this argues that we found a high risk of NAFLD in CD in the last calendar period when we had the greatest coverage of liver disease since the Swedish Patient Registry began registering also hospital-based outpatient visits in 2001.

Although the difference in NAFLD risk estimates between age groups did not attain statistical significance, we speculate that the higher risk in children (4-fold increase) is due to fewer competing factors and comorbidities, and lower risk of misclassification. Although we tried to exclude alcohol-induced fatty liver, we cannot rule out that some NAFLD cases were due to alcohol intake in older people, but less likely so in younger study participants. Hence, it is possible that misclassification of NAFLD has diluted the true association with CD and underestimated the HR for NAFLD especially in older individuals.

Conclusion

In conclusion, individuals with CD seem to be at increased risk of NAFLD compared to the general population, a risk that diminishes in magnitude, but persists over the long term. These findings should be confirmed in a population of NAFLD patients where excess alcohol intake has been ruled out and the diagnosis has been confirmed through liver biopsy.

Supplementary Material

Log-minus-log curve examining proportional hazards.

Acknowledgments

Funding: NRR: No funding source

BL was supported by The National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, National Institutes of Health (UL1 TR000040).

JFL was supported by grants from the Swedish Society of Medicine, the Swedish Research Council, and the Swedish Celiac Society.

None of the funders had any influence on this study.

Abbreviations used in this article

- CD

Celiac disease

- NAFLD

Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease

- NASH

Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis

- SIBO

Small intestinal bacterial overgrowth

- VA

Villous atrophy

- ICD

International Classification of Disease (codes)

- CI

Confidence Interval

- HR

Hazard ratio

- OR

Odds ratio

- BMI

body mass index

Appendix

Table 1a. Comparison of small intestinal histopathology classifications.

| Classification used in this project | Villous atrophy | Marsh 1-2 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Marsh Classification | Type IIIa | Type IIIb | Type IIIc | Type II | Type I |

| Marsh Description | Flat destructive | Infiltrative / infiltrative-hyperplastic | |||

| Corazzaet al (A) | Grade B1 | Grade B2 | Grade A | ||

| SnoMed Codes | M58, D6218, M58005 | M58, D6218, M58006 | M58, D6218, M58007 | M40-M43, M47000, M47170 | |

| KVAST/Alexander classification | III Partial VA |

IV Subtotal VA |

IV Total VA |

Intraepithelial lymphocytosis (IELs) | |

| Characteristics | |||||

| Villous atrophy | + | ++ | ++ | - | - |

| IEL# | + | + | + | + | + |

| Crypt hyperplasia | + | ++ | ++ | + | - |

Comparison of small intestinal histopathology classifications. Corazza GR, Villanacci V, Zambelli C,et al. Comparison of the interobserver reproducibility with different histologic criteria used in CD. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. Jul 2007;5(7):838-843.

Table 2a.

Celiac disease and NAFLD. Adjusted analyses.

| Adjustment for: | Hazard ratio; 95% CI Celiac and risk of later NAFLD |

Odds ratio; 95% CI Celiac disease and prior NAFLD |

|---|---|---|

| Not adjusted | 2.8; 2.0-3.9 | 3.9; 2.8-5.5 |

| Country of birth, socio-economy, education | 2.8; 2.0-3.9 | 3.8; 2.7-5.4 |

| Type 2 diabetes, autoimmune thyroid disease, lipid treatment and other drugs previously linked to NAFLD* | 2.7; 1.8-4.0 | Not calculated due to lack of events# |

CI, Confidence interval.

Reference is general population comparator cohort

See main text for explanation. These analyses were restricted to individuals with a follow-up after July 1, 2005. For the odds ratio analysis we had planned to restrict data to individuals having a biopsy after July 1, 2005 and developing NAFLD. However, very few individuals both had a biopsy after this date and a NAFLD diagnosis – hence we did not calculate any odds ratio adjusted for type 2 diabetes, autoimmune thyroid disease, lipid treatment and other drugs previously linked to NAFLD.

Alcohol-related diseases: ICD7: 280.00; 281.00; 307.00; 307.10; 307.99; 322; 581.10; 583.10; ICD8: 261.00; 262.00; 291; 303; 571.00; 571.01; 979; 980.00; 980.01; 980.98; 980.99; ICD9: 291; 303; 305A; 357F; 425F; 535D; 571A-D; 760W; 790D; 977D; 980A; 980X; V97B; ICD10: F10; G31.2; G62.1; G72.1; I42.6; K29.2; K70; K86.0; Q35.4; R78.9; T51.0; T51.8; T51.9; X65; Y15; Y57.3; Y90; Y91; Z50.2; Z71.4; Z71.2

Autoimmune thyroid disease: ICD-7: 252.00, 252.01, 252.02, 253.10, 253.19, 253.20, 253.29, 254.00, ICD-8: 242.00, 242.09, 244, 245.03, ICD-9: 242A, 242X, 244X, 245C, 245W, ICD-10: E03.5, E03.9, E05.0, E05.5, E05.9, E06.3, E06.5

Type 2 diabetes: ICD-10: E11

Drugs (ATC codes): Lipid-lowering drugs (proxy for dyslipidemia): C10; Amiodarone: C01BD01; Corticosteroids: H02AB; Methotrexate: L04AX03; Tamoxifen: L02BA01; Tetracycline: J01AA.

Footnotes

Authors' contributions: ICMJE criteria for authorship read and met: NR, BL, RH, PG, JFL.

Agree with the manuscript's results and conclusions: NR, BL, RH, PG, JFL.

Designed the experiments/the study: NR, JFL.

Collected data: JFL

Analyzed the data: JFL

Wrote the first draft of the paper: NR and JFL.

Contributed to study design, interpretation of data and writing: BL, RH, PG.

Interpretation of data; approved the final version of the manuscript: NR, BL, RH, PG, JFL

Responsible for data integrity: JFL.

Obtained funding: JFL.

Conflict of Interest: None.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Rubio-Tapia A, Murray JA. The liver in celiac disease. Hepatology. 2007;46:1650–1658. doi: 10.1002/hep.21949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ludvigsson JF, Elfstrom P, Broome U, Ekbom A, Montgomery SM. Celiac disease and risk of liver disease: a general population-based study. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;5:63–69. e61. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2006.09.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barshop NJ, Sirlin CB, Schwimmer JB, Lavine JE. Review article: epidemiology, pathogenesis and potential treatments of paediatric non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2008;28:13–24. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2008.03703.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vernon G, Baranova A, Younossi ZM. Systematic review: the epidemiology and natural history of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and non-alcoholic steatohepatitis in adults. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2011;34:274–285. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2011.04724.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Powell EE, Cooksley WG, Hanson R, Searle J, Halliday JW, Powell LW. The natural history of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis: a follow-up study of forty-two patients for up to 21 years. Hepatology. 1990;11:74–80. doi: 10.1002/hep.1840110114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Abenavoli L, Milic N, De Lorenzo A, Luzza F. A pathogenetic link between nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and celiac disease. Endocrine. 2013;43:65–67. doi: 10.1007/s12020-012-9731-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Patton HM, Yates K, Unalp-Arida A, Behling CA, Huang TT, Rosenthal P, et al. Association between metabolic syndrome and liver histology among children with nonalcoholic Fatty liver disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105:2093–2102. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2010.152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Margariti A, Deutsch M, Manolakopoulos S, Tiniakos D, Papatheodoridis GV. The severity of histologic liver lesions is independent of body mass index in patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2013;47:280–286. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0b013e31826be328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Promrat K, Kleiner DE, Niemeier HM, Jackvony E, Kearns M, Wands JR, et al. Randomized controlled trial testing the effects of weight loss on nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Hepatology. 2010;51:121–129. doi: 10.1002/hep.23276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bhat G, Baba CS, Pandey A, Kumari N, Choudhuri G. Life style modification improves insulin resistance and liver histology in patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. World J Hepatol. 2012;4:209–217. doi: 10.4254/wjh.v4.i7.209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Reilly NR, Aguilar K, Hassid BG, Cheng J, Defelice AR, Kazlow P, et al. Celiac disease in normal-weight and overweight children: clinical features and growth outcomes following a gluten-free diet. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2011;53:528–531. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e3182276d5e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cheng J, Brar PS, Lee AR, Green PH. Body mass index in celiac disease: beneficial effect of a gluten-free diet. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2010;44:267–271. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0b013e3181b7ed58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Norsa L, Shamir R, Zevit N, Verduci E, Hartman C, Ghisleni D, et al. Cardiovascular disease risk factor profiles in children with celiac disease on gluten-free diets. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19:5658–5664. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v19.i34.5658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Peters U, Askling J, Gridley G, Ekbom A, Linet M. Causes of death in patients with celiac disease in a population-based Swedish cohort. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163:1566–1572. doi: 10.1001/archinte.163.13.1566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Volynets V, Kuper MA, Strahl S, Maier IB, Spruss A, Wagnerberger S, et al. Nutrition, intestinal permeability, and blood ethanol levels are altered in patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) Dig Dis Sci. 2012;57:1932–1941. doi: 10.1007/s10620-012-2112-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Alisi A, Manco M, Devito R, Piemonte F, Nobili V. Endotoxin and plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 serum levels associated with nonalcoholic steatohepatitis in children. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2010;50:645–649. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e3181c7bdf1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Miele L, Valenza V, La Torre G, Montalto M, Cammarota G, Ricci R, et al. Increased intestinal permeability and tight junction alterations in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatology. 2009;49:1877–1887. doi: 10.1002/hep.22848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wigg AJ, Roberts-Thomson IC, Dymock RB, McCarthy PJ, Grose RH, Cummins AG. The role of small intestinal bacterial overgrowth, intestinal permeability, endotoxaemia, and tumour necrosis factor alpha in the pathogenesis of non-alcoholic steatohepatitis. Gut. 2001;48:206–211. doi: 10.1136/gut.48.2.206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Heyman M, Abed J, Lebreton C, Cerf-Bensussan N. Intestinal permeability in coeliac disease: insight into mechanisms and relevance to pathogenesis. Gut. 2012;61:1355–1364. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2011-300327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rubio-Tapia A, Barton SH, Rosenblatt JE, Murray JA. Prevalence of small intestine bacterial overgrowth diagnosed by quantitative culture of intestinal aspirate in celiac disease. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2009;43:157–161. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0b013e3181557e67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Day CP, James OF. Steatohepatitis: a tale of two “hits”? Gastroenterology. 1998;114:842–845. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(98)70599-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ludvigsson JF, Otterblad-Olausson P, Pettersson BU, Ekbom A. The Swedish personal identity number: possibilities and pitfalls in healthcare and medical research. Eur J Epidemiol. 2009;24:659–667. doi: 10.1007/s10654-009-9350-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ludvigsson JF, Brandt L, Montgomery SM. Symptoms and signs in individuals with serology positive for celiac disease but normal mucosa. BMC Gastroenterol. 2009;9:57. doi: 10.1186/1471-230X-9-57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ludvigsson JF, Montgomery SM, Ekbom A, Brandt L, Granath F. Small-intestinal histopathology and mortality risk in celiac disease. JAMA. 2009;302:1171–1178. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ludvigsson JF, Andersson E, Ekbom A, Feychting M, Kim JL, Reuterwall C, et al. External review and validation of the Swedish national inpatient register. BMC Public Health. 2011;11:450. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-11-450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Olen O, Bihagen E, Rasmussen F, Ludvigsson JF. Socioeconomic position and education in patients with coeliac disease. Dig Liver Dis. 2012;44:471–476. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2012.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ludvigsson JF, Brandt L, Montgomery SM, Granath F, Ekbom A. Validation study of villous atrophy and small intestinal inflammation in Swedish biopsy registers. BMC Gastroenterol. 2009;9:19. doi: 10.1186/1471-230X-9-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Itoh S, Yougel T, Kawagoe K. Comparison between nonalcoholic steatohepatitis and alcoholic hepatitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 1987;82:650–654. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rahimi AR, Daryani NE, Ghofrani H, Taher M, Pashaei MR, Abdollahzade S, et al. The prevalence of celiac disease among patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in Iran. Turk J Gastroenterol. 2011;22:300–304. doi: 10.4318/tjg.2011.0216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bardella MT, Valenti L, Pagliari C, Peracchi M, Fare M, Fracanzani AL, et al. Searching for coeliac disease in patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Dig Liver Dis. 2004;36:333–336. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2004.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kabbani TA, Kelly CP, Betensky RA, Hansen J, Pallav K, Villafuerte-Galvez JA, et al. Patients with celiac disease have a lower prevalence of non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus and metabolic syndrome. Gastroenterology. 2013;144:912–917. e911. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2013.01.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kalsch J, Bechmann LP, Manka P, Kahraman A, Schlattjan M, Marth T, et al. Non-alcoholic steatohepatitis occurs in celiac disease and is associated with cellular stress. Z Gastroenterol. 2013;51:26–31. doi: 10.1055/s-0032-1330421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.van Elburg RM, Uil JJ, Mulder CJ, Heymans HS. Intestinal permeability in patients with coeliac disease and relatives of patients with coeliac disease. Gut. 1993;34:354–357. doi: 10.1136/gut.34.3.354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Giorgio V, Miele L, Principessa L, Ferretti F, Villa MP, Negro V, et al. Intestinal permeability is increased in children with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, and correlates with liver disease severity. Dig Liver Dis. 2014 doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2014.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Riordan SM, McIver CJ, Thomas DH, Duncombe VM, Bolin TD, Thomas MC. Luminal bacteria and small-intestinal permeability. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1997;32:556–563. doi: 10.3109/00365529709025099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mohler KM, Sleath PR, Fitzner JN, Cerretti DP, Alderson M, Kerwar SS, et al. Protection against a lethal dose of endotoxin by an inhibitor of tumour necrosis factor processing. Nature. 1994;370:218–220. doi: 10.1038/370218a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ludvigsson JF, Wahlstrom J, Grunewald J, Ekbom A, Montgomery SM. Coeliac disease and risk of tuberculosis: a population based cohort study. Thorax. 2007;62:23–28. doi: 10.1136/thx.2006.059451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ludvigsson JF, Sanders DS, Maeurer M, Jonsson J, Grunewald J, Wahlstrom J. Risk of tuberculosis in a large sample of patients with coeliac disease--a nationwide cohort study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2011;33:689–696. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2010.04572.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ludvigsson JF, Brandt L, Montgomery SM, Granath F, Ekbom A. Validation study of villous atrophy and small intestinal inflammation in Swedish biopsy registers. BMC Gastroenterol. 2009;9:19. doi: 10.1186/1471-230X-9-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Carjsö KSB, Spetz CL. Evaluation of the Data quality in the Swedish National Hospital Discharge Register. Book Evaluation of the Data quality in the Swedish National Hospital Discharge Register. 1998:1–10. (Editor edˆeds) City: WHO/HST/ICD/C/98.34. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Walker MM, Murray JA, Ronkainen J, Aro P, Storskrubb T, D'Amato M, et al. Detection of Celiac Disease and Lymphocytic Enteropathy by Parallel Serology and Histopathology in a Population-Based Study. Gastroenterology. 2010;139:112–119. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.04.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Olen O, Montgomery SM, Marcus C, Ekbom A, Ludvigsson JF. Coeliac disease and body mass index: A study of two Swedish general population-based registers. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2009;44:1198–1206. doi: 10.1080/00365520903132013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Review T, LaBrecque DR, Abbas Z, Anania F, Ferenci P, Khan AG, et al. World Gastroenterology Organisation global guidelines: Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2014;48:467–473. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0000000000000116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.OECD. Health at a Glance: Europe 2012. Chapter 2.6.1. Alcohol consumption among population aged 15 years and over, 2010 and change, 1980-2010. 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 45.Brown I, Mino-Kenudson M, Deshpande V, Lauwers GY. Intraepithelial lymphocytosis in architecturally preserved proximal small intestinal mucosa: an increasing diagnostic problem with a wide differential diagnosis. Archives of pathology & laboratory medicine. 2006;130:1020–1025. doi: 10.5858/2006-130-1020-ILIAPP. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.