Abstract

Background

There is compelling evidence from over 60 epidemiological studies that smoking significantly reduces the risk of Parkinson’s disease (PD). In general, those who currently smoke cigarettes, as well as those with a past history of such smoking, have a reduced risk of PD compared to those who have never smoked. Recently it has been suggested that a cardinal non-motor sensory symptom of PD, olfactory dysfunction, may be less severe in PD patients who smoke than in PD patients who do not, in contrast to the negative effect of smoking on olfaction described in the general population.

Methods

We evaluated University of Pennsylvania Smell Identification Test (UPSIT) scores from 323 Parkinson’s patients and 323 controls closely matched individually on age, sex, and smoking history (never, past, current).

Results

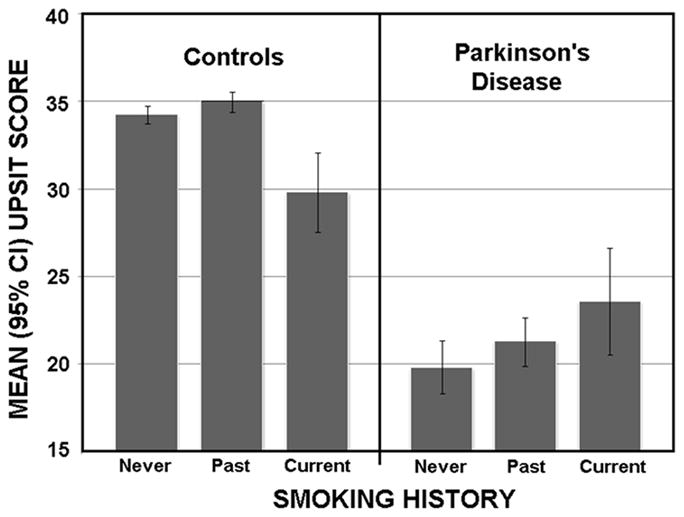

The patients exhibited much lower UPSIT scores than did the controls (P<0.0001). The relative decline in dysfunction of the current PD smokers was less than that of the never- and past-PD smokers (respective Ps=0.0005 & 0.0019). The female PD patients outperformed their male counterparts by a larger margin than did the female controls (3.66 vs. 1.07 UPSIT points; respective Ps < 0.0001 & 0.06). Age-related declines in UPSIT scores were generally present (P < 0.0001). No association between the olfactory measure and smoking dose, as indexed by pack years, was evident.

Conclusions

PD patients who currently smoke do not exhibit the smoking-related decline in olfaction observed in non-PD control subjects who currently smoke. The physiologic basis of this phenomenon is yet to be defined.

Keywords: Parkinson’s disease, olfaction, psychophysics, UPSIT, cigarette smoking, L-DOPA

Introduction

Prospective and retrospective epidemiological studies have reported a significant inverse association between smoking and Parkinson’s disease (PD).1–4 PD risk is lowest among subjects with the longest duration of smoking, the greatest lifetime dose of smoking, the most cigarettes smoked per day, and, in past smokers, the fewest years since quitting.

Among the most salient sensory signs of PD is olfactory dysfunction -- dysfunction that adversely influences safety, food flavor, and quality of life.5–8 In some cases, the deficit occurs years before the onset of the cardinal motor symptoms.9 PD-related pathology likely begins within the olfactory bulbs, the anterior olfactory nucleus, and the dorsal motor nucleus of the vagal glossopharyngeal nerve complex, only later affecting the substantia nigra.10

In light of such findings, does smoking also influence the magnitude of PD-related olfactory dysfunction? Two relative small studies have addressed this question. Lucassen et al.11 found higher scores on the University of Pennsylvania Smell Identification Test (UPSIT) in 22 smokers with PD than in 54 PD patients who had never smoked (p<0.02). Moccia et al.12 found no UPSIT differences between 10 PD current smokers and 58 PD never-smokers. However, 10 currently smoking controls underperformed 51 never-smoking controls, suggesting that smoking protected against olfactory dysfunction in their PD cohort.

We sought to more definitively establish whether present or past smoking alters the olfactory dysfunction of PD by using data from a large number of PD patients and healthy controls matched on the basis of sex, age, and smoking history.

Methods

Subjects

Data from 323 PD patients and 323 matched normal controls were obtained from previous studies (e.g.,13–16), from the Movement Disorders Center at Pennsylvania Hospital, Philadelphia, and from the Parkinson’s Disease Research, Education, and Clinical Center of the Philadelphia VA Medical Center. Once the subject numbers noted Table 1 had been reached, data recruitment was stopped for the never- and past-smoking groups. All current smoking PD patients that could be identified were included in the study.

Table 1.

Subject demographics.

| Subject Group | Smoking Status | Sex | N | Mean Age (SD) | Number with H&Y Score | Mean H&Y Score (SD) | Number taking PD-related Medications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PD | Never | M | 111 | 62.9 (10.6) | 87 | 2.2 (0.7) | 39 |

| F | 39 | 66.6 (8.2) | 10 | 2.3 (1.1) | 39 | ||

| Past | M | 111 | 67.1 (9.8) | 90 | 2.4 (0.8) | 35 | |

| F | 39 | 64.1 (9.4) | 25 | 2.3 (0.9) | 23 | ||

| Current | M | 17 | 58.8 (11.3) | 10 | 2.4 (0.7) | 5 | |

| F | 6 | 69.0 (6.9) | 2 | 3.0 (0.0) | 3 | ||

| Control | Never | M | 111 | 62.8 (10.6) | NA | NA | NA |

| F | 39 | 66.7 (8.3) | NA | NA | NA | ||

| Past | M | 111 | 67.0 (9.8) | NA | NA | NA | |

| F | 39 | 63.7 (9.1) | NA | NA | NA | ||

| Current | M | 17 | 58.7 (11.4) | NA | NA | NA | |

| F | 6 | 68.8 (6.7) | NA | NA | NA |

Patients met the Gelb et al. criteria for possible PD.17 Medication usage data were available for 144 patients, 24 of whom were not taking any PD-related medications. Hoehn & Yahr (H&Y) scores were available for 224 patients. Pack years were available for all but three PD patients. The mean (SD) time elapsed between smoking cessation and test administration did not differ between the past-smoking PD patients and controls [18.4 years (10.1) vs. 19.1 years (13.2); P=0.92]. Of the 323 PD patients, 279 were perfectly matched with a control on the basis of age, sex, and smoking status (never, past, current). The remaining 44 were exactly matched to controls on the basis of sex and smoking status; they differed from their individually matched controls in age by no more than a year. Each subject had provided informed written consent and subject participation was approved by the respective institutional human subjects’ review boards.

Olfactory Testing

The UPSIT had been administered to all participants.18 This highly reliable test (test-retest r>0.90)19 correlates strongly with most other nominally disparate olfactory tests, including detection threshold tests.18;20 This test is sensitive to sex and changes in olfactory function related to age and many diseases, including Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s, and myasthenia gravis.6;8;18;21–25

Statistical Analyses

UPSIT scores were subjected to analysis of covariance (ANCOVA; age = covariate) with the between subjects factor of sex and the within subjects factor of subject group (PD patients, matched controls). Analyses of variance (ANOVAs) assessed interaction effects. Control minus PD UPSIT scores were similarly analyzed to assess the relative PD-related declines in olfactory function. Partial correlations controlling for age were computed among selected measures.

Results

The mean (95% CI) UPSIT scores are presented in Figure 1. Overall, the patients exhibited much lower scores than did the controls [F (1,316)=20.50, P<0.0001]. The age covariate was significant [F (1,315)=41.96, P<0.00001], reflecting the well-known age-related decline in UPSIT scores. Significant interactions between subject group (PD, controls) and both sex [F (1,316)=7.35, P=0.007] and smoking group [F (2,316)=7.05, P<0.001] were present. The female PD patients outperformed their male counterparts by an average of 3.66 UPSIT points (22.54 vs. 18.88; P<0.0001), as compared to the female controls, who outperformed their male counterparts by an average of 1.07 UPSIT points (34.77 vs. 33.70; P=0.054). While the UPSIT scores of both the never and past smoking PD groups differed significantly from their respective matched control groups (ps<0.0001), this was not the case for the current smokers (p=0.59). Although no difference in the control minus PD olfactory deficit was present between PD past smokers and PD never smokers (P=0.79), that of the PD current smokers [8.48 (9.83)] was less than that of the PD never smokers [14.85 (9.92)] (P=0.0005) and the past PD smokers [14.32 (9.80] (P=0.0019).

Figure 1.

No significant associations were present between pack years and either the UPSIT scores or the control minus PD UPSIT difference scores in the current or past smoking PD subjects. Among past smokers, the time elapsed since smoking cessation also did not correlate with these measures, and no significant difference in PD-related olfactory dysfunction was found between the patients on and off PD-related medications. No meaningful correlation was observed between UPSIT deficits and H&Y scores.

Discussion

The present study found that, relative to matched controls, olfactory function was less attenuated in current cigarette smokers with PD than in past or never smokers with PD. It should be emphasized, however, that this effect was due, in part, to the poorer performance of the currently smoking non-PD controls, contributing to the smaller difference in relative test scores (Figure 1). Nonetheless, the PD patients who currently smoked did not exhibit the smoking-related decline in function observed in the non-PD controls. This finding accords well with the earlier observations of Lucassen et al.11 and Moccia et al.12

While it is conceivable that PD patients who continue to smoke have less advanced disease, evidence that disease stage influences UPSIT scores in a meaningful manner is weak or generally lacking.15;26 Interestingly, olfactory dysfunction secondary to exposure to some airborne toxins is less in smokers than in non-smokers, suggesting that smoking may protect the olfactory system from xenobiotic damage.27;28 Such protection could reflect nicotine’s influences on the cholinergic system. Enhancement of cholinergic function in animals, humans, and animal models of PD facilitates odor detection performance29–31 and damage to this system can alter the ability to smell.32 The cholinergic system is associated with olfactory dysfunction in a number of neurodegenerative diseases32 and nicotine from cigarette smoke directly stimulates and up-regulates pre-synaptic nicotine receptors within basal forebrain regions associated with olfactory processing.33 Nicotine increases blood flow within the olfactory bulb,34 counteracts free radical formation induced by olfactory bulb damage,35 and, in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease, reduces beta-amyloidosis within the olfactory tract.36 Nicotine likely influences the delicate balance between CNS immune system quiescence and activation.37 Interestingly, nicotine directly activates olfactory receptor neurons via cAMP-mediated canonical olfactory receptor pathways rather than through nicotinic cholinergic receptors.38 Whether such activation promotes maintenance of olfactory function is unknown. The reason why the influences of nicotine are apparent in PD patients, but not in controls, conceivably reflects enhancement of function of a damaged but not intact olfactory epithelium. While PD-related improvement in UPSIT scores may relate to cholinergic influences on non-olfactory elements involved an odor identification task, such as attention or word finding,39 such effects would have to be more accentuated in PD than in healthy controls to produce the current findings.

The major strengths of our study are the large cohort of PD patients and controls individually matched on age, sex, and smoking histories and the use of a highly reliable and well-validated olfactory test. Limitations include the relatively small sample size of the current smoking groups and the lack of complete details regarding medication use (e.g., cholinergic agonists) and smoking behavior (e.g., time since smoking cessation and type of cigarettes smoked).

Acknowledgments

Supported by USAMRAA W81XWH-09-1-046 and NIDCD 00161 (RL Doty, PI). We thank John Duda, M.D., Matthew B. Stern, M.D., and Suzanne Reichwein for their assistance in providing information on some of the PD subjects evaluated in this study. We extend a particular thanks to the patients who agreed to participate in our studies.

R.L.D. received grant support from the National Institutes of Health (RO1 MH 059852) and Department of Defense (USAMRAA W81XWH-09-1-046). He is a consultant to NIH grants RO1 AG041795 and U54 HD028138, and a mentor on NIH K01 MH090548-01. He is President and major shareholder of Sensonics International., a manufacturer and distributor of tests of taste and smell, including the UPSIT. He received publishing royalties from Cambridge University Press and Johns Hopkins University Press. He received an honorarium from the University of Florida and lodging reimbursement as Chairperson of the Other Non-Motor Features of Parkinson’s Disease working group of the Parkinson Study Group. He received consulting fees from Pfizer, Inc., Acorda Therapeutics, and several law offices.

F.E.L. received funding from the Department of Defense (USAMRAA W81XWH-09-1-046) and consulting fees from Sensonics International.

D.W. has received research funding from Michael J. Fox Foundation for Parkinson’s Research, National Institutes of Health, Novartis Pharmaceuticals, Department of Veterans Affairs, and Alzheimer’s Disease Cooperative Study; honoraria from Teva Pharmaceuticals, Lundbeck Inc., Pfizer, Avanir Pharmaceuticals, Acadia Pharmaceuticals, Merck & Co., UCB, Bristol-Myers Squibb Company, Novartis Pharmaceuticals, Clintrex LLC, Theravance, Medivation, CHDI Foundation, Alzheimer’s Disease Cooperative Study and the Weston Foundation; license fee payments from the University of Pennsylvania for the QUIP and QUIP-RS; and fees for testifying in two court cases related to impulse controls disorders in Parkinson’s disease (March, 2013-April, 2014, payments by Eversheds and Roach, Brown, McCarthy & Gruber, P.C.).

Footnotes

Author Roles

1. Research Project: A. Conception; B. Organization; C. Execution;

2. Statistical Analysis: A. Design; B. Execution; C. Review and Critique

3. Manuscript Preparation: A. Writing the First Draft; B. Review and Critique.

J.D.S.: 1B; 1C; 2A; 2B; 2C: 3A, 3B

J.F.M.: 2C; 3B

F.E.L: 1B; 3B

R.L.D.: 1A, 1B, 1C, 2A, 2B, 2C, 3B

D.W.: 1B, 3B

Financial Disclosures: Dr. Doty is President and major shareholder in Sensonics, International, the manufacturer of the commercial version of the University of Pennsylvania Smell Identification Test. This research project was supported by USAMRAA W81XWH-09-1-0467 and NIDCD 00161 (RL Doty, PI).

Financial Disclosures:

Last 12 months:

J.D.S. is a student at Pennsylvania State University and received no funding in relation to this project.

References

- 1.Morens DM, Grandinetti A, Reed D, White LR, Ross GW. Cigarette smoking and protection from Parkinson's disease - False association or etiologic clue? Neurology. 1995;45:1041–1051. doi: 10.1212/wnl.45.6.1041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hernan MA, Zhang SM, Rueda-deCastro AM, Colditz GA, Speizer FE, Ascherio A. Cigarette smoking and the incidence of Parkinson's disease in two prospective studies. Ann Neurol. 2001;50:780–786. doi: 10.1002/ana.10028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chen H, Huang X, Guo X, et al. Smoking duration, intensity, and risk of Parkinson disease. Neurology. 2010;74:878–884. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181d55f38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Thacker EL, O'Reilly EJ, Weisskopf MG, et al. Temporal relationship between cigarette smoking and risk of Parkinson disease. Neurology. 2007;68:764–768. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000256374.50227.4b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aden E, Carlsson M, Poortvliet E, et al. Dietary intake and olfactory function in patients with newly diagnosed Parkinson's disease: a case-control study. Nutr Neurosci. 2011;14:25–31. doi: 10.1179/174313211X12966635733312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Doty RL, Kamath V. The influences of age on olfaction: a review. Front Psychol -- Cogn Sci. 2014;5:20. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2014.00020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Deems DA, Doty RL, Settle RG, et al. Smell and taste disorders, a study of 750 patients from the University of Pennsylvania Smell and Taste Center. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1991;117:519–528. doi: 10.1001/archotol.1991.01870170065015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Doty RL. Olfaction in Parkinson's disease and related disorders. Neurobiol Dis. 2012;46:527–552. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2011.10.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ross W, Petrovitch H, Abbott RD, Tanner CM, Popper J, Masaki K. Association of olfactory dysfunction with risk of future Parkinson's disease. Movement Dis. 2005;20:S129–S130. doi: 10.1002/ana.21291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Braak H, Del TK, Rub U, De Vos RA, Jansen Steur EN, Braak E. Staging of brain pathology related to sporadic Parkinson's disease. Neurobiol Aging. 2003;24:197–211. doi: 10.1016/s0197-4580(02)00065-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lucassen EB, Sterling NW, Lee EY, et al. History of smoking and olfaction in Parkinson's disease. Mov Disord. 2014;29:1069–1074. doi: 10.1002/mds.25912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Moccia M, Picillo M, Erro R, et al. How does smoking affect olfaction in Parkinson's disease? J Neurol Sci. 2014;340:215–217. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2014.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Doty RL, Stern MB, Pfeiffer C, Gollomp SM, Hurtig HI. Bilateral olfactory dysfunction in early stage treated and untreated idiopathic Parkinson's disease. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiat. 1992;55:138–142. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.55.2.138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Morley JF, Weintraub D, Mamikonyan E, Moberg PJ, Siderowf AD, Duda JE. Olfactory dysfunction is associated with neuropsychiatric manifestations in Parkinson's disease. Mov Disord. 2011;26:2051–2057. doi: 10.1002/mds.23792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Doty RL, Deems DA, Stellar S. Olfactory dysfunction in parkinsonism: a general deficit unrelated to neurologic signs, disease stage, or disease duration. Neurology. 1988;38:1237–1244. doi: 10.1212/wnl.38.8.1237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Doty RL, Shaman P, Applebaum SL, Giberson R, Siksorski L, Rosenberg L. Smell identification ability: changes with age. Science. 1984;226:1441–1443. doi: 10.1126/science.6505700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gelb DJ, Oliver E, Gilman S, Gelb DJ, Oliver E, Gilman S. Diagnostic criteria for Parkinson disease. Arch Neurol. 1999;56:33–39. doi: 10.1001/archneur.56.1.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Doty RL, Shaman P, Dann M. Development of the University of Pennsylvania Smell Identification Test: a standardized microencapsulated test of olfactory function. Physiol Behav. 1984;32:489–502. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(84)90269-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Doty RL, Newhouse MG, Azzalina JD. Internal consistency and short-term test-retest reliability of the University of Pennsylvania Smell Identification Test. Chem Senses. 1985;10:297–300. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cain WS, Rabin RD. Comparability of two tests of olfactory function. Chem Senses. 1989;14:479–485. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Doty RL, Bromley SM, Stern MB. Olfactory testing as an aid in the diagnosis of Parkinson's disease: development of optimal discrimination criteria. Neurodegeneration. 1995;4:93–97. doi: 10.1006/neur.1995.0011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Leon-Sarmiento FE, Bayona EA, Bayona-Prieto J, Osman A, Doty RL. Profound olfactory dysfunction in myasthenia gravis. PLoS One. 2012;7:e45544. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0045544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Marmura MJ, Monteith TS, Anjum W, Doty RL, Hegarty SE, Keith SW. Olfactory function in migraine both during and between attacks. Cephalalgia. 2014;28:50–53. doi: 10.1177/0333102414527014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Doty RL, Beals E, Osman A, et al. Suprathreshold odor intensity perception in early-stage Parkinson's disease. Mov Disord. 2014;29:1208–1212. doi: 10.1002/mds.25946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Doty RL, Reyes PF, Gregor T. Presence of both odor identification and detection deficits in Alzheimer's disease. Brain Res Bull. 1987;18:597–600. doi: 10.1016/0361-9230(87)90129-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Doty RL, Riklan M, Deems DA, Reynolds C, Stellar S. The olfactory and cognitive deficits of Parkinson's disease: evidence for independence. Ann Neurol. 1989;25:166–171. doi: 10.1002/ana.410250210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schwartz BS, Ford DP, Bolla KI, Agnew J, Rothman N, Bleecker ML. Solvent-associated decrements in olfactory function in paint manufacturing workers. Amer J Indust Med. 1990;18:697–706. doi: 10.1002/ajim.4700180608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schwartz BS, Doty RL, Monroe C, Frye R, Barker S. Olfactory function in chemical workers exposed to acrylate and methacrylate vapors. Amer J Pub Health. 1989;79:613–618. doi: 10.2105/ajph.79.5.613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Doty RL, Bagla R, Kim N. Physostigmine enhances performance on an odor mixture discrimination test. Physiol Behav. 1999;65:801–804. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9384(98)00238-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mandairon N, Peace ST, Boudadi K, et al. Compensatory responses to age-related decline in odor quality acuity: cholinergic neuromodulation and olfactory enrichment. Neurobiol Aging. 2011;32:2254–2265. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2009.12.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chambers RP, Call GB, Meyer D, et al. Nicotine increases lifespan and rescues olfactory and motor deficits in a Drosophila model of Parkinson's disease. Behav Brain Res. 2013;253:95–102. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2013.07.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Doty RL. Olfactory dysfunction in Parkinson disease. Nat Rev Neurol. 2012;8:329–339. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2012.80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pauly JR, Marks MJ, Gross SD, Collins AC. An autoradiographic analysis of cholinergic receptors in mouse brain after chronic nicotine treatment. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1991;258:1127–1136. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shiba K, Machida T, Uchida S, Hotta H. Effects of nicotine on regional blood flow in the olfactory bulb in rats. Eur J Pharmacol. 2006;546:148–151. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2006.06.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tunez I, Drucker-Colin R, Montilla P, et al. Protective effect of nicotine on oxidative and cell damage in rats with depression induced by olfactory bulbectomy. Eur J Pharmacol. 2010;627:115–118. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2009.10.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nordberg A, Hellstrom-Lindahl E, Lee M, et al. Chronic nicotine treatment reduces beta-amyloidosis in the brain of a mouse model of Alzheimer's disease (APPsw) J Neurochem. 2002;81:655–658. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2002.00874.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Minghetti L, Ajmone-Cat MA, De Berardinis MA, De SR. Microglial activation in chronic neurodegenerative diseases: roles of apoptotic neurons and chronic stimulation. Brain Res Brain Res Rev. 2005;48:251–256. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2004.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bryant B, Xu J, Audige V, Lischka FW, Rawson NE. Cellular basis for the olfactory response to nicotine. ACS Chem Neurosci. 2010;1:246–256. doi: 10.1021/cn900042c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schubert CR, Cruickshanks KJ, Fischer ME, et al. Odor identification and cognitive function in the Beaver Dam Offspring Study. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol. 2013;35:669–676. doi: 10.1080/13803395.2013.809701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]