Abstract

Background

It has been known that skeletal muscles show atrophic changes after prolonged sedation or general anesthesia. Whether these effects are due to anesthesia itself or to disuse during anesthesia has not been fully clarified. Autophagy dysregulation has been implicated in muscle wasting conditions. This study tested the hypothesis that the magnitude of skeletal muscle autophagy is affected by both anesthesia and immobility.

Methods

The extent of autophagy was analyzed chronologically during general anesthesia. In vivo microscopy was performed using green fluorescent protein-tagged LC3 for detection of autophagy using sternomastoid muscles of live mice during pentobarbital anesthesia (n = 6 to 7). Western blotting and histological analyses were also conducted on tibialis anterior muscles (n = 3 to 5). To distinguish the effect of anesthesia from that due to disuse, autophagy was compared between animals anesthetized with pentobarbital and those immobilized by short-term denervation without continuation of anesthesia. Conversely, tibialis anterior and sternomastoid muscles were electrically stimulated during anesthesia.

Results

Western blots and microscopy showed time-dependent autophagy upregulation during pentobarbital anesthesia, peaking at 3 h (728.6+/− 93.5% of basal level, mean +/−SE). Disuse by denervation without sustaining anesthesia did not lead to equivalent autophagy, suggesting that anesthesia is essential to causes autophagy. In contrast, contractile stimulation of the tibialis anterior and sternomastoid muscles significantly reduced the autophagy upregulation during anesthesia (85% at 300 min). Ketamine, Ketamine plus xylazine, isoflurane, and propofol also upregulated autophagy.

Conclusions

Short-term disuse without anesthesia does not lead to autophagy, but anesthesia with disuse leads to marked upregulation of autophagy.

INTRODUCTION

Autophagy is a degradation mechanism of cellular components, and is highly conserved among species. It is a consensus that autophagy is required for cell survival and many physiological processes. Cellular stresses often yield autophagosomes inside the cytoplasm, or engulfment of cellular components such as mitochondria and cytoplasm. Since the discovery of a series of autophagy-related genes,1 molecular mechanisms of autophagy induction and turnover have been clarified.2 During cellular stress (e.g., starvation, oxidative stress), a series of autophagy-related molecules (Atgs) are activated including LC3 (a.k.a. Atg8).3 LC3, synthesized as a full-length precursor pro-LC3, is immediately processed by another autophagy molecule Atg4 into the cleaved form, LC3I, and resides in the cytosol. Upon induction of autophagy, cytosolic LC3I is lipidated by ubiquitin-like modification involving Atg3 and Atg7. The lipidated form, LC3II, is incorporated into autophagosomes. Thus LC3 dot formation in tissue by immunohistochemistry and use of green fluorescent protein (GFP)-LC3 transgenic mice, or LC3II immunoblots are often used for quantification of autophagosomes. Autophagosomes eventually lyse with lysosomes and degrade and recycle the cellular constituents including proteins and organelles. There is growing body of evidence that autophagy or its defect is involved in many forms of congenital and acquired muscle diseases.4–6 Despite numerous publications on autophagy using cell culture, autophagy experiments with interventions on live animals faces technical limitations. In order to avoid confounding effect of anxiety and stress on animal studies, the experimental animals are often anesthetized. If general anesthesia per se causes autophagy, the interpretation of the data becomes complicated and the experimental design and results require careful consideration, because the potential confounding effect of general anesthesia on autophagy may mask the effect of therapeutic interventions. General anesthesia upregulates autophagy in some organs,7 but the comprehensive time course of its activity or the assessment of its mechanism has not been available especially in skeletal muscles.

It has been known that prolonged sedation or general anesthesia leads to skeletal muscle atrophy. General anesthesia is associated with metabolic changes in various organs with reports documenting both upregulation and suppression of apoptosis.8–10 While many general anesthetics exert protective effect on many organs,11 it shows neurotoxic effect in some cases.12 Given that autophagy pathway interacts with apoptotic and cytoprotective signaling, it seems important to examine the role of anesthesia on autophagy. It has been established that immobilization induces muscle atrophy accompanied with autophagy.13 Since general anesthesia concomitantly causes the state of immobilization or disuse, it is thus expected that prolonged anesthesia could upregulate autophagy. This phenomenon, however, has not been studied in detail.

In this study, we tested the hypothesis that anesthesia per se induces autophagy in the skeletal muscle in a time-dependent manner and this autophagy can be mitigated by prevention of immobility. The effect of various anesthetics including pentobarbital, isoflurane, propofol and ketamine on autophagy was also tested.

MATERIALS & METHODS

Materials

Mouse strain: Transgenic mice (GFP-LC3/C57BL/6JJcl) expressing an autophagosome maker, GFP-LC3, were purchased from RIKEN BioResource Center (Ibaraki, Japan) and cross-mated more than seven times onto the background strain, C57BL/10SnJ mice, which was from Jackson Laboratories (Bar Harbor, ME). C57BL/10SnJ mice served as wild type mice for nontransgenic studies. Antibodies: anti-LC3 and anti-glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase were from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO) and Abnova U.S.A. (Walnot, CA), respectively.

Animal study design

All the procedures in the animal experiments were reviewed and approved by Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Massachusetts General Hospital (the Subcommittee on Research Animal Care, Boston, Massachusetts.). Different animals were used for each experiment, and when tissue harvest was involved, animals were euthanized with overdose of pentobarbital (200 mg/kilogram [kg] body weight [BW]). The anesthetic and time course of experiment is described in each section. Since the preliminary studies indicated that autophagy is significantly upregulated after 2 h of anesthesia, peaking at 3 hours, most samples were analyzed at 2–3 h after anesthesia as shown in figure 1–3.

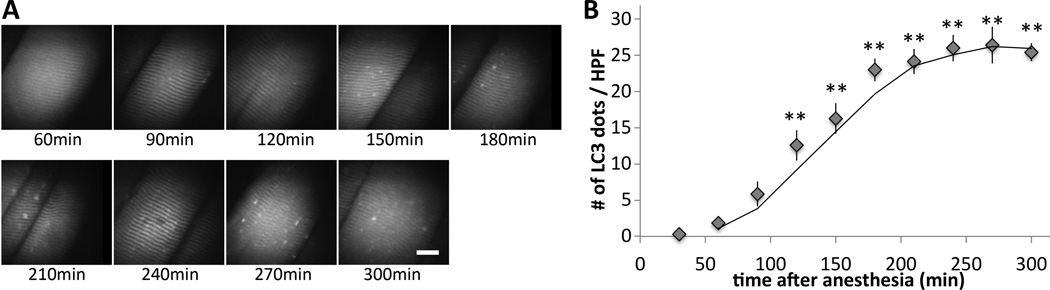

Figure 1. In vivo microscopy reveals chronological increase of autophagosome vesicles in the skeletal muscle under anesthesia.

(A) During anesthesia with pentobarbital, the sternomastoid muscle of a GFP-LC3 transgenic mouse was exposed and observed under the confocal microscope up to 300 min after anesthesia. White bar represent 20µm. (B) The numbers of autophagosome dots per high power field (HPF) were plotted against the time (min) after anesthesia. Seven different animals were monitored by scanning the entire sternomastoid muscle of the same animal at each time point throughout the time course. Anesthesia by pentobarbital increased autophagosome formation in a time-dependent manner. Average value from the four mice is shown with the standard error bar. The described time course is based on the time from anesthesia induction. ** p<0.01 at all points after 120 min by repeated measures ANOVA and Dunnett’s multiple comparison post-hoc test (n=7).

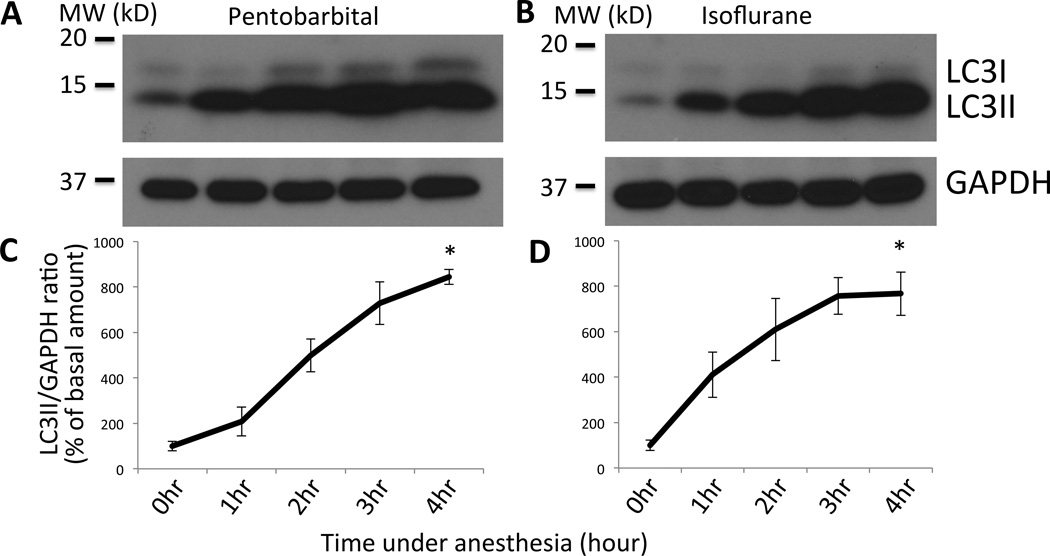

Figure 3. Western blot of LC3 shows upregulation of autophagy in a time-dependent manner after anesthesia.

(A&B) Tibialis anterior muscles were harvested from wild type mice at different time points (0 – 4 h) after anesthesia with pentobarbital (A) or isoflurane (B), homogenized, separated by SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, and blotted with anti-LC3 antibody. Increased LC3II was observed after pentobarbital injection. Loading control with GAPDH blotting is shown in the bottom panel. Bars to the left of the figure represent the molecular weightin kilodalton (‘MW (kD)’). (C&D) Densitometry of each band was performed and the ratio of LC3II/GAPDH was calculated for samples with anesthesia by pentobarbital (C) or isoflurane (D). Relative ratio of LCII/GAPDH as compared to the basal value at time 0 was plotted in percentage with the standard error. *p<0.05 by Friedman’s nonparametric test with Dunn’s post-hoc analysis (n=3). With ANOVA and Dunnett’s multiple comparison test, p<0.05 at 2 h and p<0.01 at 3 and 4 h for pentobarbital, p<0.01 after 2 h for isoflurane. The labeling for the time course of each time point in the lower panels (C&D) corresponds to each lane of the upper gel figures (A&B). GAPDH = Glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase.

Numbers of animals

The numbers of animals used were seven in each group for figure 1, five for figure 2, three for figure 3, four for figure 4, three to four in figure 5, six for figure 6, and four for figure 7, respectively. Sample size was determined by power analysis with both α and β values 0.05 except for figure 5 and 6 where maximum numbers of samples were restricted by the design of the gel blot. Representative results from three to four independent experiments are shown in each Western blot.

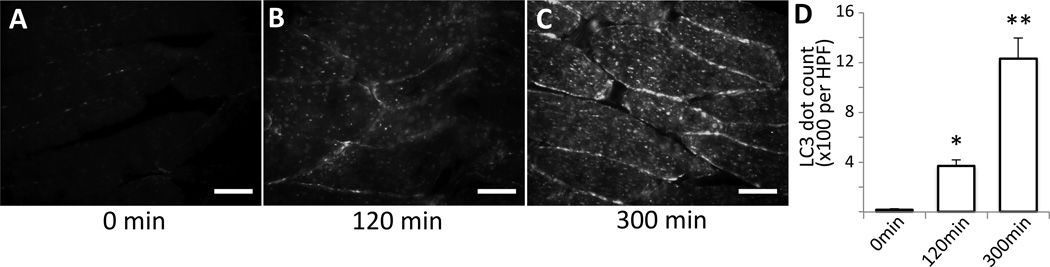

Figure 2. Histology confirms upregulation of autophagy during anesthesia.

(A–C) Tibialis anterior muscle samples were harvested from GFP-LC3 transgenic mice at different time points after anesthesia (A: 0 min, B: 120 min, C: 300 min), snap frozen, cryosectioned, fixed, and observed under fluorescent microscope. Images were captured with exactly the same exposure and gain condition for all of the samples. The numbers of LC3-GFP dots were increased in a time-dependent manner. White bar represent 50µm. (D) GFP-LC3 dot numbers were counted and expressed as mean +/− S.E. per high power field (HPF) in the bar graph. *p<0.05, **p<0.01 by ANOVA with Dunnett’s post-hoc test (n=5).Min = minutes after induction of anesthesia.

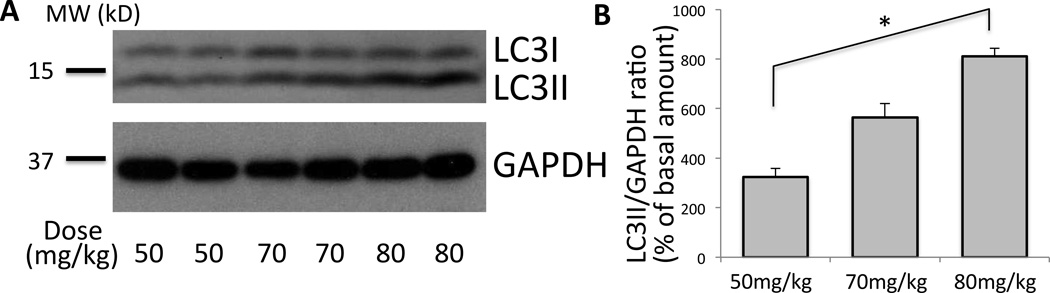

Figure 4. Dose-response of pentobarbital effect on skeletal muscle autophagy.

(A) The effect on autophagy after the initial anesthesia induction dose of 50, 70, and 80mg/kg of pentobarbital was compared (milligrams ‘mg’ of pentobarbital per kilograms ‘kg’ of body weight). Maintenance dose was injected at 60 min and 90 min with 0.4 times of the initial dose (per hour). Total homogenate of tibialis anterior muscle was run on SDS-PAGE and blotted against LC3 and GAPDH. (B) Densitometry was performed for each band. Relative ratio of LCII/GAPDH as compared to the basal value with no pentobarbital treatment was plotted in percentage with the standard error. Higher dose at 80mg/kg (milligrams of pentobarbital per kilograms of body weight) resulted in more autophagy than lower dose with 50mg/kg (*p<0.05, Kruskal-Wallis test, Dunn’s post-hoc test, n=4). Two representative samples in each group are shown.GAPDH = Glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase; MW (kD) = molecular weight in kilodalton.

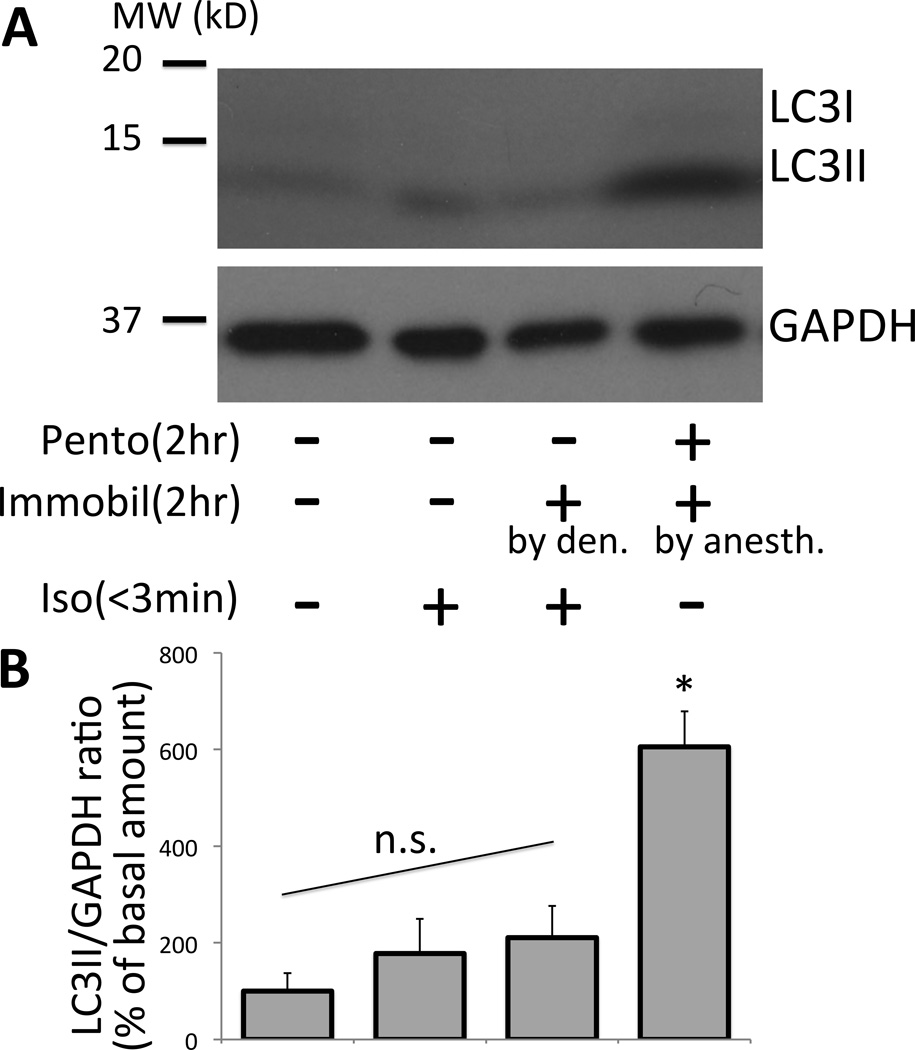

Figure 5. Immobilization by denervation is not sufficient to cause equivalent amount of autophagy as compared to immobilization by anesthesia with pentobarbital.

(A) The effect of 2-h muscle inactivity (immobilization) due to denervation (Pento −, Immobil + [by den.], Iso +) on autophagy was compared to two hour pentobarbital anesthesia (Pento +, Immobil + [by anesth.], Iso −). The total homogenate of tibialis anterior muscle was run for immunoblotting against LC3 and GAPDH. The effect of anesthesia was minimized by limiting the time for surgery to less than 3min. Contralateral side (Pento −, Immobil −, Iso +) or freshly harvested sample (Pento −, Immobil −, Iso −) served as references to show basal level of autophagy. (B) The amount of LC3II in the blot was assessed by densitometry and shown as percentage of the basal value without pentobarbital, isoflurane or immobilization (*p<0.05, Kruskal-Wallis test with Dunn’s comparison, n=3–4). By ANOVA with Tukey’s comparison, pentobarbital anesthetized sample showed higher amount of LC3II than any other group (p<0.01). n.s. = No statistical difference was found among the denervation only control (Pento −, Immobil + [by den.], Iso +) and two other references (left two columns). Note that pentobarbital anesthesia sets the muscle in the immobile state due to the effect of anesthesia but not due to denervation or pin-immobilization. Thus, this group is labeled as ‘Pento +, Immobil + [by anesth.] ‘.The labeling for each treatment in (A) corresponds to each quantification column in (B).GAPDH = Glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase; MW (kD) = molecular weight in kilodalton; Pento = pentobarbital; Immobil = immobilization; Iso = isoflurane; den = denervation; anesth = anesthesia.

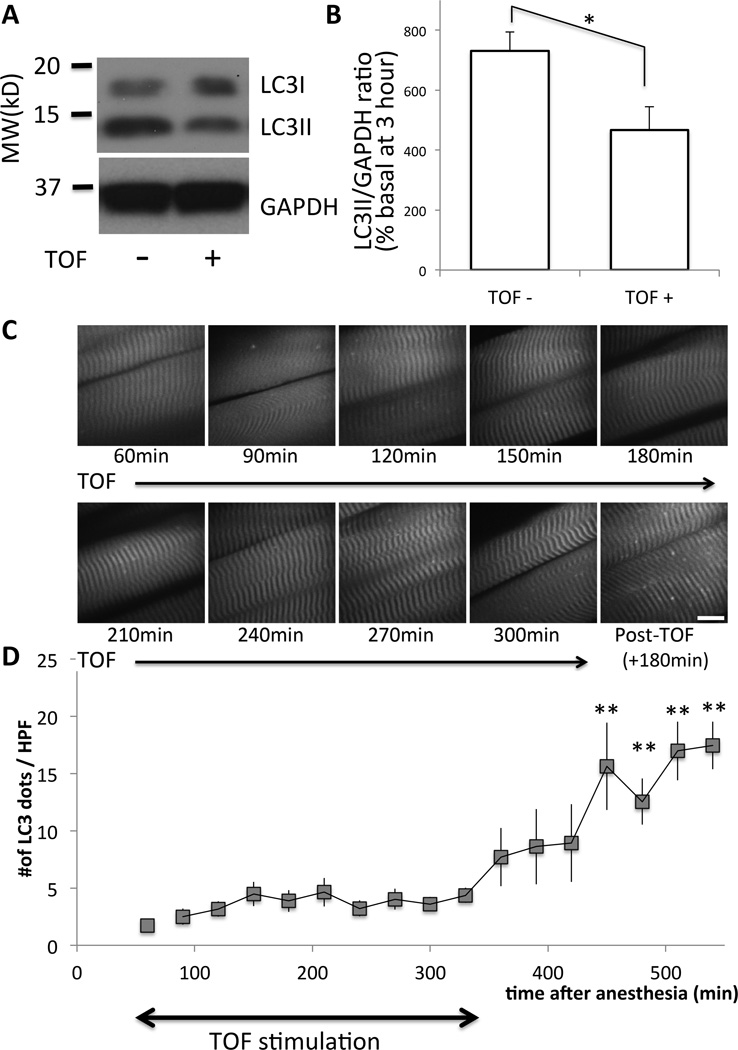

Figure 6. Electrical stimulation of the muscle reduces the amount of autophagy.

(A) Tibialis anterior muscles BL6 mice with (‘+’) or without (‘−‘) train-of-four (TOF) stimulation (continuous with 12-s interval) were harvested at 3 h after pentobarbital anesthesia and Western blots were performed for LC3 and GAPDH (as the loading control). Bars to the left of the figure represent the molecular size in kilodalton, (‘MW (kD)’). (B) Densitometric quantification of six different mice is shown as the bar graph. Relative ratio of LCII/GAPDH as compared to the basal value of freshly harvested tissue was plotted in percentage with the standard error. As compared to samples without TOF stimulation (‘TOF-‘), those with TOF (‘TOF+’) showed significantly reduced amount of LC3I and LC3II (*p<0.05, paired Student t-test, n=6). (C) Under pentobarbital anesthesia, the sternomastoid muscle of a GFP-LC3 transgenic mouse was exposed and observed under the confocal microscope up to 540 min after anesthesia. During the first 300 min (from 60min to 360min), electrical TOF stimulation was continuously applied at 12-s intervals. At 360 min, the stimulation was stopped and the muscles were observed another 180 min. (D) The numbers of autophagosome dots per high power field (HPF) were plotted against the time after anesthesia. Time-dependent increase of autophagosome formation by pentobarbital was suppressed by muscle activity both in tibialis anterior and sternomastoid muscles. Average value from n=6 is shown with the standard error bar. **p<0.01 by repeated measure ANOVA with Dunnett’s post-hoc test (n=6) as compared to the start of measurement (60min). GAPDH = Glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase; MW (kD) = molecular weight in kilodalton.

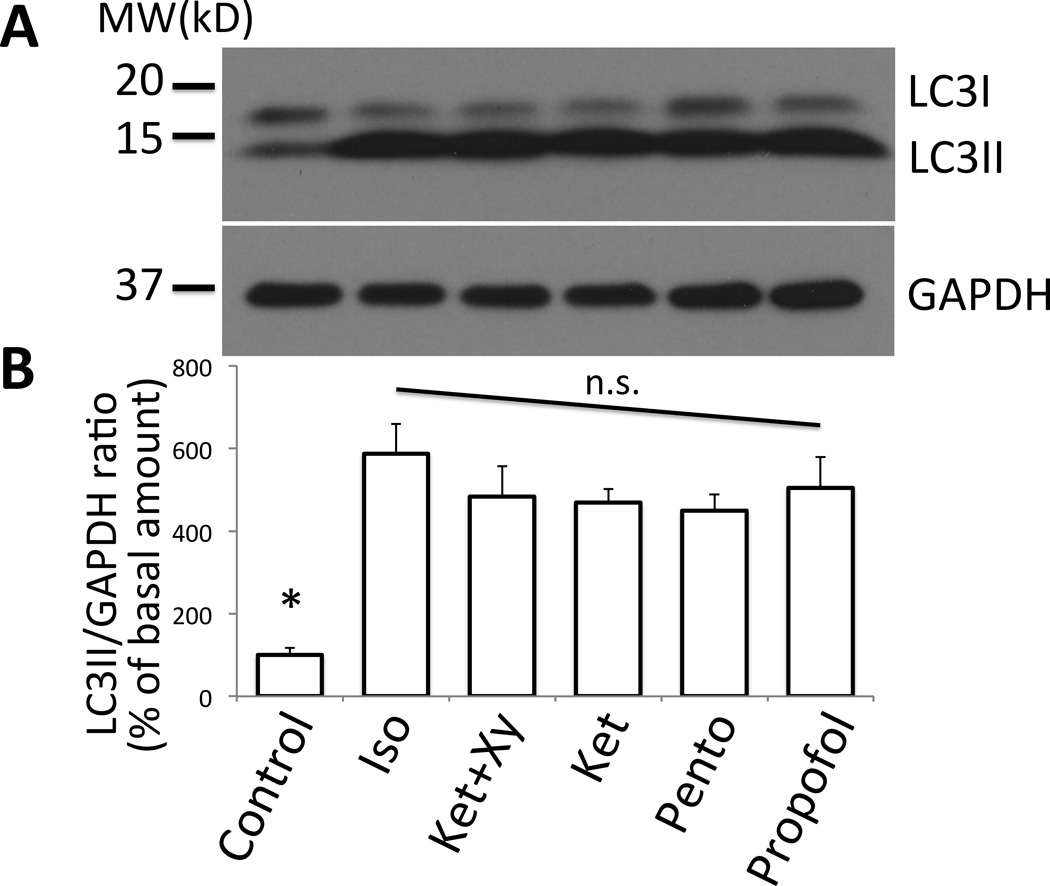

Figure 7. Effect of different anesthetics on autophagy.

(A) Anesthesia was induced in BL6 mice using different anesthetics including isoflurane (‘Iso’), ketamine+xylazine (‘Ket+Xy’), ketamine (‘Ket’), pentobarbital (‘Pento’), or propofol (‘Propofol’). The tibialis anterior muscle samples were harvested at 2 h and were analyzed by Western blots together with control sample. As compared to the control, all samples from anesthetized mice showed increased LC3II species, indicative of upregulation of autophagy. As the loading control, GAPDH (glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase) was blotted. (B) Densitometry of each band was performed and the ratio of LC3II/GAPDH was calculated. Relative ratio of LCII/GAPDH as compared to the basal value at time 0 was plotted in percentage with the standard error. * LC3II/GAPDH ratio of control was smaller than any group receiving an anesthetic (p<0.05, Kruskal-Wallis test with Dunn’s comparison, n=4). By ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparison, all anesthetic treatments were significantly higher than control (p<0.01). No statistical difference was found among anesthetics (n.s.). MW (kD) = molecular weight in kilodalton. The labeling for each treatment in the quantification panel (B) corresponds to each lane of the gel picture in (A).

Anesthesia regimen

For induction of anesthesia, the following anesthetics were given either by intraperitoneal injection or inhalation route in different animal groups. During isoflurane anesthesia, oral endotracheal intubation was performed. Initial intraperitoneal bolus dose of pentobarbital was 65 mg/kg BW unless otherwise stated. After the initial dose of pentobarbital, the maintenance dose was administered intraperitoneally after 1 h every 30 min throughout the experiment at the rate of 20–32 mg/kg BW/h (proportional to the initial dose described above, with default maintenance dose 26 mg/kg/h). The induction and maintenance doses for ketamine, xylazine, propofol and isoflurane were, 100 mg/kg BW and 50 mg/kg BW/h (ketamine), 10 mg/kg BW and 5 mg/kg BW/h (xylazine), 38 mg/kg BW and 108 mg/kg BW/h (propofol), and 5% and later 1.5% (isoflurane), respectively. For studying effects of deep anesthesia with pentobarbital (70–80 mg/kg for figure 4) or prolonged anesthesia (fig. 1 & 6), oral intubation of trachea along with mechanical ventilation with ambient-room air was performed (tidal volume 0.01 ml/g BW at 120 breaths/min). With isoflurane anesthesia (fig. 7), after initial 5% isoflurane, 1.5% isoflurane with mechanical ventilation at FIO2 1.0 was used for maintenance anesthesia. Spontaneous breathing was maintained in other experiments. The default dose of pentobarbital and the doses chosen for other anesthetics were 10–20% beyond ED50 (the median effective dose to yield loss of reflex effect in 50% population)14–17 or minimum alveolar concentration18 and thus provided sufficient depth of anesthesia.

In vivo microscopy

Mice were anesthetized with pentobarbital, intubated orally, and mechanically ventilated with room air. Sternomastoid muscles were exposed and observed under the confocal microscope with water-dipping objective lenses as described (n = 6–7).19–22 The same animals were monitored throughout the time course. The entire length and width of sternomastoid muscle was scanned at each time point as described.19 Arbitrary 5 locations of sternomastoid muscle were chosen for quantification of the average numbers of autophagosomes per high power field (HPF) of observation. The validity of autophagosome countings was confirmed by an independent researcher who did not participate in the experiment and was blinded with the identity of the data (the counting was within 10% difference, R2 = 0.912 by regression analysis).

Electrical stimulation

In order to study the confounding effects of immobility on autophagy, the muscle was stimulated intermittently during anesthesia. Bipolar electrical stimulation of train-of-four (TOF) pattern was given to the sternomastoid muscle via NerveStimulator (Fisher) as described19. Briefly, probes were placed at both ends of the sternomastoid muscle and electrical pulses of 20 mA at 2 Hz was given every 14 s. This condition provided supramaximal stimulation.19 Tibialis anterior muscle was also studied with and without stimulation of the sciatic nerve with bipolar electrode at the supramaximal voltage.23

Short-term denervation experiment

To distinguish the effect of anesthesia itself from that of disuse, the tibialis anterior muscle was immobilized for 2 h by denervation of the sciatic nerve. Mice were anesthetized briefly for the denervation with 1.5% isoflurane. Immediately the wound was closed, and the animals were awakened. The entire procedure was completed within three minutes. After 2 h of free motion, the animals (n = 4) were euthanized and the denervated and undenervated tibialis anterior muscles were harvested.

Western blotting

Western Blotting was performed according to the standard procedure.21 Harvested samples were homogenized in a homogenization buffer (20 mM Tris/hydrochloric acid (pH 7.6), 150 mM sodium chloride, 2% TritonX100, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 5 µg/ml aprotinin, 10 µg/ml leupeptin, 10 µg/ml pepstatin A, and 0.5 mM dithiothreitol). Crude total homogenate was collected after low-speed centrifugation (500 xg, 10 min). After measuring the protein amount of the total homogenate, equal amount of protein was loaded and separated on polyacrylamide gel, transferred to polyvinylidene fluoride or nitrocellulose membrane and blotted against antibodies of interest.

Histology

Post-mortem detection of autophgosomes was performed in GFP-LC3 transgenic mice as follows: At predetermined time after induction of anesthesia, muscle samples were harvested, embedded in Optimual Cutting Temperature tissue compound (Sakura Finetek VWR, Randor, PA), and snap frozen in 2-methylbutane precooled in dry ice. The frozen samples were cryosectioned, acetone-fixed and visualized for the GFP-LC3 dots. The amount of autophagosomes per myofiber was recorded.

Statistical Analyses

For comparing the two groups, Student t-test was used after confirming he normality of sample distribution with Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. For comparison among three groups or more, ANOVA with Dunnett’s post-hoc test was used after confirming the normality. In experiments where sample numbers in each group was small (less than five), Kruskal-Wallis nonparametric test with Dunn’s comparison analyses for multiple or paired groups was used. P value less than 0.05 based on two-tailed analysis was considered as statistically significant. For the time-course studies, repeated measures ANOVA with Dunnett’s comparison was used for studies with equal to or more than six samples after confirming normality, and Friedman’s non-parametric analysis with Dunn’s test was used for less than five samples. Sample size was determined by power analysis with α value 0.05 and β value<0.2. In multiple group comparison, Bonferroni’s correction was combined. In the dose response experiment, the expected ratio of LC3II/glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase and the standard deviation for the lowest and highest dose were 0.11+/−0.04 versus 0.28+/−0.06. The statistical calculation was performed using GraphPad Prism (GraphPad Software, Inc., La Jolla, CA). The results are given as mean +/− S.E in the graphs unless otherwise stated.

RESULTS

To examine whether anesthesia with pentobarbital causes autophagy in the skeletal muscle, LC3 dot formation in sternomastoid muscle was observed in vivo using GFP-LC3 transgenic mice using an in vivo confocal microscope (fig. 1A). The mice used express GFP-conjugated LC3 as a marker for the autophagosomes and the increase in the numbers of LC3 dot reflect the upregulation of autophagy.24 At early time points, there were minimal amounts of LC3 dots (fig. 1A & B, 30–60 min), suggesting that the background autophagosome numbers at the basal level is low. The numbers of LC3 dots gradually increased after 120 min, peaking at 180 min after induction of anesthesia, supporting the hypothesis that autophagosomes increase in a time-dependent manner during pentobarbital anesthesia.

Next, to confirm the finding in figure 1, the tibialis anterior muscles were harvested and cryosectioned. After fixation, the tissue section was visualized under the fluorescent microscope. The numbers of autophagosomes gradually increased with time up to 3 h and maintained for 5 h, which was the end of the observation period (fig. 2). This finding is, therefore, consistent with the results from in vivo microscopy studies (fig. 1).

The upregulation of autophagy observed in GFP-LC3 mice during in vivo microscopy and with histology during pentobarbital anesthesia was further confirmed by Western Blotting using wild type mice (fig. 3). Tibialis anterior muscles were harvested at 0, 1, 2, 3, and 4 h after the induction of anesthesia with pentobarbital. Consistent with the data from GFP-LC3 mice (figs. 1 & 2), the amount of LC3II gradually increased with time, peaking after 3 h (728.6+/−93.5% of the basal level, fig. 3). To test whether the chronological increase in autophagy is specific only to pentobarbital anesthesia, samples following 1.5% isoflurane anesthesia were also analyzed. Both pentobarbital and isoflurane gave a similar time course of autophagy (fig. 3A & B, representative of three independent experiments are shown). Dose-response relationship of autophagy against pentobarbital was then examined. As shown in figure 4, higher dose (80 mg/kg) of pentobarbital gave more autophagy induction evidenced as the increased LC3II despite the fact that all doses suppressed the voluntary movements, suggesting that autophagy induction is caused by anesthetic effect.

To confirm whether the anesthesic itself and not immobilization treatment causes autophagy, distinctions were made between state of anesthesia and state of muscle inactivity. To cause state of muscle inactivity, the tibialis anterior muscle was immobilized by denervation of the sciatic nerve. Long-term effect of denervation has been studied well,25, 26 but there has been no study on short-term denervation with minimal duration of operation and anesthesia. To minimize the effect of artifactual stress related to surgery, the animals were anesthetized only briefly (<3 min) for the denervation procedure, and awakened shortly thereafter and were awake until muscle extraction under anesthesia two hours later. Compared to 2-h pentobarbital anesthesia, denervation-induced muscle inactivity for the same period did not induce comparable amount of autophagy (fig. 5). These results suggest that anesthesia-induced autophagy is caused by pentobarbital itself and possibly disuse. Short-term (2 h) muscle inactivity or immobilization alone is not enough to cause muscle autophagy.

Next, to examine whether the augmentation of autophagy was aggravated by the lack of muscle activity, electrical stimulation was applied to evoke muscle contraction. During the 3 h of anesthesia with pentobarbital, bipolar electrical stimulation was applied to the sciatic nerve yielding supramaximal contractions of tibialis anterior. Electrical stimulation (fig. 6A & B, ‘TOF+’) reduced the amount of LC3II (assessed by Western blots), suggesting that anesthesia-induced upregulation of autophagy was at least partially related to the lack of muscle activity. To confirm autophagic changes documented by Western blots, in vivo microscopy of LC3 dot formation during anesthesia was performed on sternomastoid muscles with or without bipolar direct electrical stimulation on muscles. Without TOF stimulation, anesthesia with pentobarbital yielded 24.7 dots/HPF at 300 min after the induction of anesthesia (fig. 1). With TOF stimulation, the autophagosome dot formation was suppressed to 3.60 dots/HPF (fig. 6C & D), or 14.5% of that seen without TOF. The numbers of autophagosomes stayed near the basal level up to 6 h as long as muscle contractions were continued. When electrical stimulation was terminated at 6 h, the numbers of autophagosomes increased in the muscle, confirming the hypothesis that twitch-induced muscle activity inhibits the autophagosome numbers at basal levels. Blockade of autophagy by twitch contraction suggests that muscle inactivity or immobilization is essential to aggravate anesthesia-induced autophagy.

Finally, to test whether the anesthesia-induced upregulation of autophagy was a specific event only observed with pentobarbital, or is common to all the anesthetics, different types of anesthetics were examined (fig. 7). All the anesthetics tested (pentobarbital, ketamine, ketamine+xylazine, isoflurane, propofol) showed upregulation of LC3II in tibialis anterior muscle (assessed by Western blots), suggesting that autophagy upregulation is a common phenomenon to parenteral and inhalational general anesthetics.

DISCUSSION

In the current study, anesthesia-induced skeletal muscle autophagy was shown by in vivo microscopy, histology, and Western blotting. The amount of autophagosomes gradually increased after induction and maintenance of anesthesic state with pentobarbital, peaked after 3 h, and lasted at least up to 6 h. This effect seems to result directly from pentobarbital anesthesia, since short-term (2 h) denervation without sustaining anesthesia caused less amount of autophagy as compared to pentobarbital anesthesia for the same duration (fig. 5). The fact that higher dose of anesthesia caused higher amount of autophagy (fig. 4) despite the same level of muscle inactivity further augmented this notion. These results also mean that short-term muscle inactivity or immobilization alone is not sufficient to cause muscle autophagy, but anesthesia is necessary. In contrast, electrical muscle stimulation significantly suppressed the upregulation of autophagy, suggesting that anesthesia-induced skeletal muscle autophagy requires, or is at least partially mediated by, the lack of muscle activity. Thus, muscle autophagy under anesthesia requires two components; state of anesthesia and state of muscle inactivity. Lack of one or the other does not lead to marked autophagy induction.

All the tested anesthetics including pentobarbital, ketamine, ketamine plus xylazine, isoflurane, and propofol showed upregulation of autophagy. The above enumerated anesthetics are considered to exert their anesthetic effects via different mechanisms. The fact that all anesthetics tested induced autophagy indirectly confirms the hypothesis that muscle inertia plus anesthetic state is an important component of anesthesia-induced muscle autophagy.

Previous studies have demonstrated that general anesthesia induces modification of microtubule organization.27, 28 Dynamic regulation of the microtubule network plays an essential role in the induction and maturation of autophagosomes.29 It is possible that general anesthesia has a direct impact on autophagy via microtubule reorganization. It is also known that general anesthetics induce alterations in mitochondrial functions.30, 31 It has been established that disturbed mitochondria are cleared by mitophagy, or the autophagic degradation of mitochondria.32 These previous lines of evidence do not contradict the hypothesis that anesthesia directly induces autophagy, given that mitophagy is the form of autophagy to sequester and clear dysfunctional mitochondria and shares the common mechanisms with autophagy.33

Some patients with background skeletal muscle illnesses including myopathies and dystrophies are at risk for general anesthesia-related complications.34–38 Some of these muscle diseases show abnormal autophagy functions. Given accumulating knowledge about the involvement of autophagy in various muscle wasting conditions and muscle atrophy, the result of the current study suggests the importance of more detailed studies on autophagy functions in anesthesia-related complications for such high-risk patients. Since immobilization-induced muscle weakness is a risk factor in patients treated in the intensive care unit, where prolonged sedation with ketamine, propofol or even inhalation anesthetic is provided, further characterization and detailed mechanistic investigation is required to attribute the precise roles of immobilization and anesthetics in the induction of skeletal muscle autophagy.

Although the current study documented that autophagy induction is common to all anesthetics tested, including pentobarbital, ketamine, propofol, and isoflurane, future studies are required for elucidation of which anesthetic causes more potent autophagy dysregulation (or upregulation). Previous studies demonstrated that prolonged immobilization39 or denervation25 upregulates autophagy in the skeletal muscles. Our short-term immobilization via denervation did not lead to prominent autophagy upregulation as compared to the same duration of anesthesia, but it does not contradict the previous experimental results with long-term immobilization/denervation. Probably, the immobilization−/denervation-induced upregulation of autophagy is a chronic response involving proautophagic gene transcription26 and should be different from the response to the short-term disuse.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

We thank Fumito Ichinose, M.D., Ph.D., Shizuka Kashiwagi, M.D., and Mohammed Khan, Ph.D (Department of Anesthesiology, Critical Care and Pain Medicine, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts), Yusuke Norimatsu, M.D., Ph.D. and Michio Nagashima, M.D. (Jichi Medical University, Tochigi, Japan), Hajime Iwasaki, M.D. and Tomoki Sasakawa, M.D. (Asahikawa Medical University, Asahikawa, Japan), Robert Crowther, B.S. (formerly Shriners Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts) for critical advice.

Funding Source: This work was supported by a research grant funded by Shriners Hospital (to SY, Tampa, Florida) by Massachusetts General Hospital Department of Anesthesia, Critical Care and Pain Medicine Department Fund (to SY, Boston, Massachusetts) and partly by National Institute of Health P-50 GM2500: Project-I (to JAJM, Bethesda, Maryland).

Footnotes

Competing Interests: The authors declare no competing interests.

REFERENCE

- 1.Tsukada M, Ohsumi Y. Isolation and characterization of autophagy-defective mutants of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. FEBS Lett. 1993;333:169–174. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(93)80398-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nakatogawa H, Suzuki K, Kamada Y, Ohsumi Y. Dynamics and diversity in autophagy mechanisms: Lessons from yeast. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2009;10:458–467. doi: 10.1038/nrm2708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shpilka T, Weidberg H, Pietrokovski S, Elazar Z. Atg8: An autophagy-related ubiquitin-like protein family. Genome Biol. 2011;12:226. doi: 10.1186/gb-2011-12-7-226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fanin M, Nascimbeni A, Angelini C. Muscle atrophy in limb girdle muscular dystrophy 2a: A morphometric and molecular study. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol. 2013;39:762–771. doi: 10.1111/nan.12034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fanin M, Nascimbeni AC, Angelini C. Muscle atrophy, ubiquitin-proteasome, and autophagic pathways in dysferlinopathy. Muscle Nerve. 2014;50:340–347. doi: 10.1002/mus.24167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Spitali P, Grumati P, Hiller M, Chrisam M, Aartsma-Rus A, Bonaldo P. Autophagy is impaired in the tibialis anterior of dystrophin null mice. PLoS Curr. 2013;5 doi: 10.1371/currents.md.e1226cefa851a2f079bbc406c0a21e80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shiomi M, Miyamae M, Takemura G, Kaneda K, Inamura Y, Onishi A, Koshinuma S, Momota Y, Minami T, Figueredo VM. Sevoflurane induces cardioprotection through reactive oxygen species-mediated upregulation of autophagy in isolated guinea pig hearts. J Anesth. 2014;28:593–600. doi: 10.1007/s00540-013-1755-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Leitzke AS, Rolland WB, Krafft PR, Lekic T, Klebe D, Flores JJ, Van Allen NR, Applegate RL, 2nd, Zhang JH. Isoflurane post-treatment ameliorates GMH-induced brain injury in neonatal rats. Stroke. 2013;44:3587–3590. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.113.001988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Li Y, Liu C, Zhao Y, Hu K, Zhang J, Zeng M, Luo T, Jiang W, Wang H. Sevoflurane induces short-term changes in proteins in the cerebral cortices of developing rats. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2013;57:380–390. doi: 10.1111/aas.12018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Li JT, Wang H, Li W, Wang LF, Hou LC, Mu JL, Liu X, Chen HJ, Xie KL, Li NL, Gao CF. Anesthetic isoflurane posttreatment attenuates experimental lung injury by inhibiting inflammation and apoptosis. Mediators Inflamm. 2013;2013:108928. doi: 10.1155/2013/108928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Li Volti G, Basile F, Murabito P, Galvano F, Di Giacomo C, Gazzolo D, Vadala S, Azzolina R, D'Orazio N, Mufeed H, Vanella L, Nicolosi A, Basile G, Biondi A. Antioxidant properties of anesthetics: The biochemist, the surgeon and the anesthetist. Clin Ter. 2008;159:463–469. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Culley DJ, Xie Z, Crosby G. General anesthetic-induced neurotoxicity: An emerging problem for the young and old? Curr Opin Anaesthesiol. 2007;20:408–413. doi: 10.1097/ACO.0b013e3282efd18b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sanchez AM, Candau RB, Bernardi H. FoxO transcription factors: Their roles in the maintenance of skeletal muscle homeostasis. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2014;71:1657–1671. doi: 10.1007/s00018-013-1513-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Arras M, Autenried P, Rettich A, Spaeni D, Rulicke T. Optimization of intraperitoneal injection anesthesia in mice: Drugs, dosages, adverse effects, and anesthesia depth. Comp Med. 2001;51:443–456. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Flecknell P. Laboratory Animal Anaesthesia. 3rd edition. London: Academic Press; 2009. pp. 19–79. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fish RE, Brown MJ, Danneman PJ, Karas AZ. Anesthesia and Analgesia in Laboratory Animals. 2nd edition. London: Academic Press; 2008. pp. 237–282. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gargiulo S, Greco A, Gramanzini M, Esposito S, Affuso A, Brunetti A, Vesce G. Mice anesthesia, analgesia, and care, Part I: Anesthetic considerations in preclinical research. ILAR J. 2012;53:E55–E69. doi: 10.1093/ilar.53.1.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sonner JM, Gong D, Li J, Eger EI, 2nd, Laster MJ. Mouse strain modestly influences minimum alveolar anesthetic concentration and convulsivity of inhaled compounds. Anesth Analg. 1999;89:1030–1034. doi: 10.1097/00000539-199910000-00039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Asai A, Sahani N, Kaneki M, Ouchi Y, Martyn JA, Yasuhara SE. Primary role of functional ischemia, quantitative evidence for the two-hit mechanism, and phosphodiesterase-5 inhibitor therapy in mouse muscular dystrophy. PLoS One. 2007;2:e806. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Asai A, Sahani N, Ouchi Y, Martyn J, Yasuhara S. In vivo micro-circulation measurement in skeletal muscle by intra-vital microscopy. J Vis Exp. 2007:e210. doi: 10.3791/210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hosokawa S, Koseki H, Nagashima M, Maeyama Y, Yomogida K, Mehr C, Rutledge M, Greenfeld H, Kaneki M, Tompkins RG, Martyn JA, Yasuhara SE. Title efficacy of phosphodiesterase 5 inhibitor on distant burn-induced muscle autophagy, microcirculation, and survival rate. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2013;304:E922–E933. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00078.2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lichtman JW, Magrassi L, Purves D. Visualization of neuromuscular junctions over periods of several months in living mice. J Neurosci. 1987;7:1215–1222. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.07-04-01215.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nagashima M, Yasuhara S, Martyn JA. Train-of-four and tetanic fade are not always a prejunctional phenomenon as evaluated by toxins having highly specific pre- and postjunctional actions. Anesth Analg. 2013;116:994–1000. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0b013e31828841e3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mizushima N. Methods for monitoring autophagy using GFP-LC3 transgenic mice. Methods Enzymol. 2009;452:13–23. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(08)03602-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.O'Leary MF, Hood DA. Denervation-induced oxidative stress and autophagy signaling in muscle. Autophagy. 2009;5:230–231. doi: 10.4161/auto.5.2.7391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhao J, Brault JJ, Schild A, Cao P, Sandri M, Schiaffino S, Lecker SH, Goldberg AL. FoxO3 coordinately activates protein degradation by the autophagic/lysosomal and proteasomal pathways in atrophying muscle cells. Cell Metab. 2007;6:472–483. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2007.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Xie J, Li Y, Huang Y, Qiu P, Shu M, Zhu W, Ou Y, Yan G. Anesthetic pentobarbital inhibits proliferation and migration of malignant glioma cells. Cancer Lett. 2009;282:35–42. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2009.02.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Culley DJ, Cotran EK, Karlsson E, Palanisamy A, Boyd JD, Xie Z, Crosby G. Isoflurane affects the cytoskeleton but not survival, proliferation, or synaptogenic properties of rat astrocytes in vitro. Br J Anaesth. 2013;110(Suppl 1):i19–i28. doi: 10.1093/bja/aet169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mackeh R, Perdiz D, Lorin S, Codogno P, Pous C. Autophagy and microtubules - new story, old players. J Cell Sci. 2013;126:1071–1080. doi: 10.1242/jcs.115626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hertsens R, Jacob W, Van Bogaert A. Effect of hypnorm, chloralosane and pentobarbital on the ultrastructure of the inner membrane of rat heart mitochondria. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1984;769:411–418. doi: 10.1016/0005-2736(84)90325-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bains R, Moe MC, Larsen GA, Berg-Johnsen J, Vinje ML. Volatile anaesthetics depolarize neural mitochondria by inhibiton of the electron transport chain. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2006;50:572–579. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-6576.2006.00988.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhang J. Autophagy and mitophagy in cellular damage control. Redox Biol. 2013;1:19–23. doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2012.11.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ding WX, Yin XM. Mitophagy: Mechanisms, pathophysiological roles, and analysis. Biol Chem. 2012;393:547–564. doi: 10.1515/hsz-2012-0119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Simpson RS, Van K. Fatal rhabdomyolysis following volatile induction in a six-year-old boy with Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy. Anaesth Intensive Care. 2013;41:805–807. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Poole TC, Lim TY, Buck J, Kong AS. Perioperative cardiac arrest in a patient with previously undiagnosed Becker's muscular dystrophy after isoflurane anaesthesia for elective surgery. Br J Anaesth. 2010;104:487–489. doi: 10.1093/bja/aeq035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Phadke A, Broadman LM, Brandom BW, Ozolek J, Davis PJ. Postoperative hyperthermia, rhabdomyolysis, critical temperature, and death in a former premature infant after his ninth general anesthetic. Anesth Analg. 2007;105:977–980. doi: 10.1213/01.ane.0000280935.90260.d0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Goresky GV, Cox RG. Inhalation anesthetics and Duchenne's muscular dystrophy. Can J Anaesth. 1999;46:525–528. doi: 10.1007/BF03013541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Girshin M, Mukherjee J, Clowney R, Singer LP, Wasnick J. The postoperative cardiovascular arrest of a 5-year-old male: An initial presentation of Duchenne's muscular dystrophy. Paediatr Anaesth. 2006;16:170–173. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9592.2005.01698.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Talbert EE, Smuder AJ, Min K, Kwon OS, Szeto HH, Powers SK. Immobilization-induced activation of key proteolytic systems in skeletal muscles is prevented by a mitochondria-targeted antioxidant. J Appl Physiol. 1985;115(2013):529–538. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00471.2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]