Abstract

Any macroscopic deformation of a filamentous bundle is necessarily accompanied by local sliding and/or stretching of the constituent filaments1,2. Yet the nature of the sliding friction between two aligned filaments interacting through multiple contacts remains largely unexplored. Here, by directly measuring the sliding forces between two bundled F-actin filaments, we show that these frictional forces are unexpectedly large, scale logarithmically with sliding velocity as in solid-like friction, and exhibit complex dependence on the filaments’ overlap length. We also show that a reduction of the frictional force by orders of magnitude, associated with a transition from solid-like friction to Stokes’s drag, can be induced by coating F-actin with polymeric brushes. Furthermore, we observe similar transitions in filamentous microtubules and bacterial flagella. Our findings demonstrate how altering a filament’s elasticity, structure and interactions can be used to engineer interfilament friction and thus tune the properties of fibrous composite materials.

Filamentous bundles are a ubiquitous structural motif used for the assembly of diverse synthetic, biomimetic and biological materials1–4. Any macroscopic deformation of such bundles is necessarily accompanied by local sliding and/or stretching of the constituent filaments4,5. Consequently, the frictional forces that arise due to interfilament sliding are an essential determinant of the overall mechanical properties of filamentous bundles. Here, we measure frictional forces between filamentous actin (F-actin), which is an essential building block of diverse biological and biomimetic materials. We bundle F-actin filaments by adding the non-adsorbing polymer polyethylene glycol (PEG). As two filaments approach each other, additional free volume becomes available to PEG coils, leading to an effective attraction known as the depletion interaction in physics and chemistry or asmacromolecular crowding in biology (Supplementary Fig. 1a; ref. 6). Besides radial interactions, the depletion mechanism also leads to interactions along the filaments’ long axes. Although the former have been extensively studied using osmotic stress techniques7, little is known about the equally important sliding interactions.

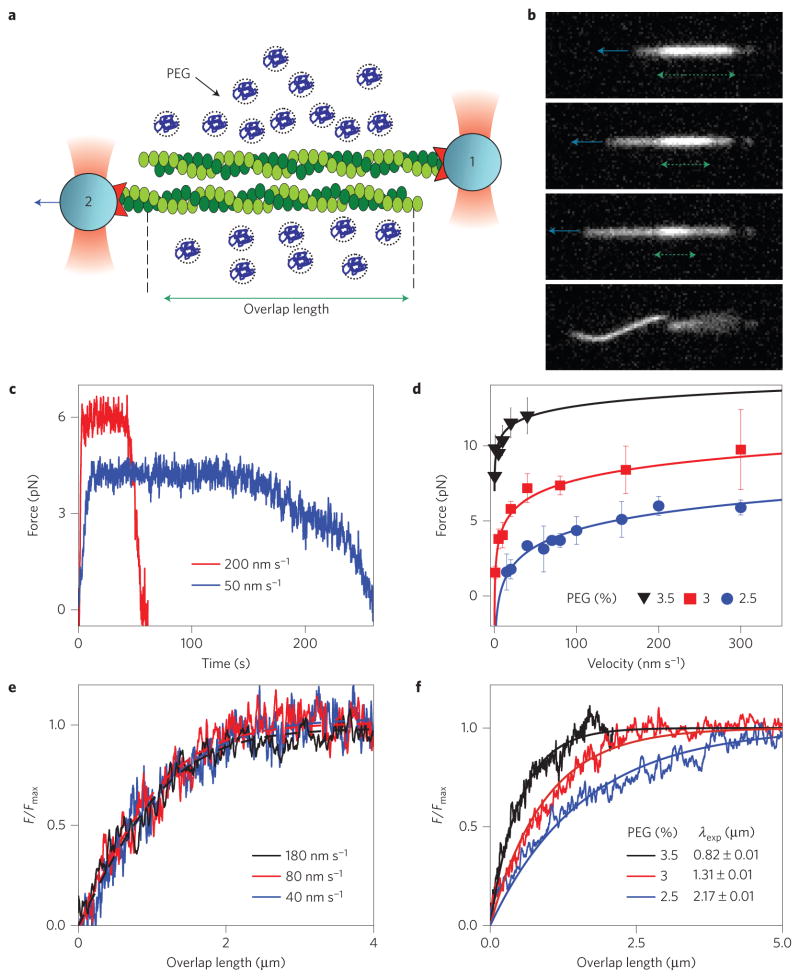

To measure sliding interactions we bundle a pair of actin filaments. Each filament is attached to a gelsolin-coated micrometre-sized bead. Such beads bind exclusively to the barbed end of F-actin, thus determining the attached filament polarity. Two filaments are held together by attractive depletion forces; subsequently, bead 2 is pulled at a constant velocity with an optical trap while the force on bead 1 is simultaneously measured (Fig. 1a,b and Supplementary Movie 1). At first, the force increases as the thermally induced filament slack is pulled out. Subsequently, the force reaches a plateau and thereafter remains constant even as the interfilament overlap length changes by many micrometres (Fig. 1c). Finally, as the overlap length becomes smaller than a characteristic length scale, the frictional force decreases exponentially and vanishes as the two filaments unbind. Increasing the sliding velocity yields a similar force profile, the only difference being a slightly elevated plateau force Fmax. Repeating these experiments at different velocities reveals that Fmax exhibits a logarithmic dependence on the sliding velocity (Fig. 1d). The strength and range of the attractive depletion potential is tuned by changing the polymer concentration and size, respectively. This feature allows us to directly relate interfilament sliding friction to cohesive interactions, simply by changing the PEG concentration. Stronger cohesion leads to a larger plateau force, Fmax (Fig. 1d).

Figure 1. Single-molecule experiments reveal frictional interactions between a pair of sliding F-actin filaments.

a, Schematic of the experimental set-up. Actin filaments attached to gelsolin-coated beads are assembled into antiparallel bundles using optical traps. Bead 2 is pulled at a constant velocity while simultaneously measuring the force exerted on bead 1. b, Sequence of images illustrating two filaments being pulled apart. The green dashed line indicates the interfilament overlap length and the blue arrow indicates the pulling direction (Supplementary Movie 1). c, Time dependence of the frictional force measured for two pulling velocities. d, The frictional force, Fmax, exhibits a logarithmic dependence on the pulling velocity. The measurements are repeated at three different cohesion strengths (PEG concentrations). Error bars indicate the s.e.m., with n = 2–13 (data points with n = 1 have no error bars). Lines indicate fits of equation (2) to experimental data. e, Dependence of the frictional force F/Fmax on the interfilament overlap length. Force profiles taken at different sliding velocities rescale onto a universal curve (equation (1)), defining a velocity-independent frictional kink width λ. f, As in e, but for different PEG concentrations, showing that stronger cohesion leads to a smaller λ. For all experiments, the salt concentration is 200 mM KCl.

These experiments reveal several notable features of sliding friction between a pair of F-actin filaments. First, even for the weakest cohesion strength required for assembly of stable bundles, the frictional force is several piconewtons, comparable to the force exerted by myosin motors. Second, above a critical value, the frictional force is independent of the interfilament overlap length. Third, the plateau force, Fmax, exhibits a logarithmic dependence on the sliding velocity. These observations are in sharp contrast with models that approximate biopolymers as a structureless filament interacting through excluded-volume interactions. Frictional coupling between such homogeneous filaments would be dominated by hydrodynamic interactions, resulting in forces that are linearly dependent on both the pulling velocity and overlap length, and orders of magnitude weaker than those measured. As these features are not observed experimentally, we exclude hydrodynamic interactions as a dominant source of frictional coupling and reconsider the basic physical processes at work.

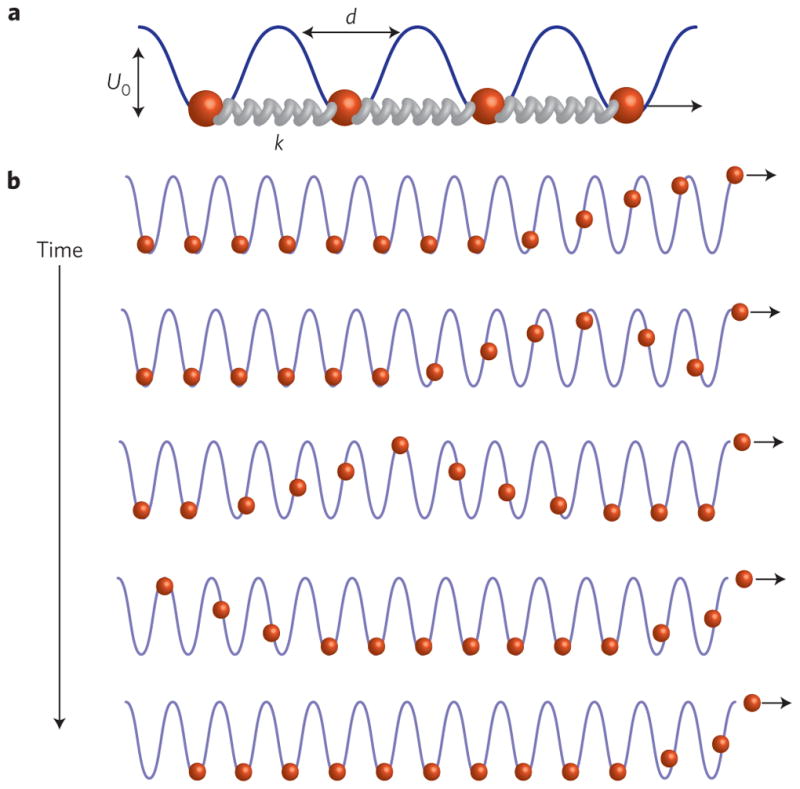

Certain aspects of the frictional interactions between actin filaments can be understood by studying the sliding dynamics of two commensurate one-dimensional (1D) lattices of beads and springs under shear (Fig. 2a). The lattices do not slide past each other rigidly. Instead, the mechanism of sliding involves the propagation of localized excitations—called kinks—that carry local compression of the lattice (Fig. 2b). Every time a kink propagates across the filament, the two intercalating lattices slide by one lattice spacing. Sliding happens locally, yielding a frictional force that is controlled by the kink width, λ, rather than the total overlap length, L, provided that L ≫ λ, as is typically the case in conventional friction. However, in our experiments the filament overlap can be controlled from nanometres to many micrometres, allowing us to examine the regime where L ≤ λ. In this regime, a propagating kink cannot fully develop and the sliding force exhibits a dependence on L.

Figure 2. 1D–Frenkel–Kontorova model accounts for the essential features of interfilament sliding friction.

a, Schematic of a model in which a sliding filament is approximated as a periodic lattice of points connected by stiff springs. A sinusoidal background potential models the interaction with the stationary filament. b, Schematic of how a filament slides by one lattice spacing in a response to an applied pulling force (Supplementary Movie 2). For filaments with finite extensibility the applied force decays over a characteristic length scale that is determined by the ratio of spring stiffness to the stiffness of the background potential. The first bead hopping over the rightmost barrier is accompanied by soliton formation that propagates leftwards. Once the soliton reaches the leftmost bead, the entire filament is translated by a lattice spacing d.

These arguments can be quantitatively rationalized within the framework of the Frenkel–Kontorova model8,9. The sliding filament is modelled as a 1D lattice of length L, comprising beads connected by springs with stiffness constant k. The lattice periodicity is given by the actin monomer spacing, d. The interaction with the stationary filament is modelled by a commensurate sinusoidal background potential of depth U0 and periodicity d. In the continuum limit, the bead displacement field, u(x), satisfies the Sine-Gordon equation, λ2uxx = sin(u(x)/d), which admits a static kink solution of the form us(x) = 4d tan−1 (e−x/λ), where λ is the kink width that corresponds to the length of the lattice that is distorted (see Supplementary Methods). Kink width is determined by the ratio of filament stiffness to the stiffness of the background potential: λ2 = kd4/U0. For very stiff filaments, such as F-actin, an imposed distortion will extend over many lattice spacings.

We first consider the case L ≤ λ and assume that the finite size chain located from x = −L to x = 0 is gradually pulled out at x = 0. The pulling force, F, displaces the rightmost bead to the maximum of the potential (that is, u(0) = d/2) generating a strain field, ux(x), that decays exponentially inside the sample with a characteristic length λ. Once the rightmost bead hops over the maximum in the potential, the whole lattice slides by d and every bead falls to the bottom of the respective potential, generating a state of vanishing strain and energy. Repeating this process n times translates the leftmost edge from −L to −L + nd. The work done by the pulling force in the nth run, F(n)d, is the energy difference between the elastic energy stored in the kink configuration us(x) and the uniform state u(x) = 0, which has zero energy. Because the elastic energy is proportional to Fmaxd sech2(x/λ) over the part of the chain still interacting with the background potential (that is, from x = L + nd to x = 0), the resulting force reads:

| (1) |

where L − nd represents the remaining overlap length between the two filaments. If the overlap length is larger than the kink width (L > λ), F(n) saturates at Fmax. In this limit, a kink nucleated at the rightmost edge can fully develop and propagate down the chain, progressively shifting the particles it leaves behind (see Supplementary Fig. 2 and Supplementary Movie 2). As a result the force ceases to depend on the overlap length. Instead, it is set by the kink width, which remains equal to the static value λ, unaffected by the kink dynamics in the overdamped regime (see Supplementary Information).

Experiments reveal that Fmax scales logarithmically with the pulling speed, v (Fig. 1d). The intuitive reason for this dependence is that, as the lattice is pulled, the particles within the kink undergo thermally assisted hopping through the periodic background potential. A classical model, originally formulated by Prandtl and Tomlinson, predicts:

| (2) |

where T is the temperature and 1/fc is the relaxation time of a monomer in a potential energy well10–13. Fitting equation (2) to the plateau value of the force–velocity curves reveals that the periodicity of the background potential is ~5 nm (Supplementary Table 1), in quantitative agreement with the F-actin monomer spacing14. This result suggests that cohering F-actin monomers intercalate with each other, and that sliding interactions require monomers to either deform or hop over each other.

Equation (1) predicts that the force profiles taken at varying pulling speeds should fall onto a master curve once rescaled by Fmax(v). This data collapse is demonstrated in Fig. 1e (Supplementary Table 2). It yields an experimental measurement of velocity-independent kink width, λ, which we compare to the theoretical prediction . We take the lattice periodicity to be 5.5 nm (ref. 14) and k to be ~7,000 pNnm−1 (ref. 15). To estimate U0 we measure the strength of the depletion-induced attraction by allowing an isolated filament to fold into a racquet-like configuration (Supplementary Fig. 1c,d; ref. 16). The size of the racquet head is directly related to the filament cohesion strength per unit length, U0. Without any adjustable parameters our theoretical model predicts values of λ which are of the same order of magnitude as those extracted from experiments (Supplementary Table 3). Increasing depletant concentration increases U0, leading to a decrease in λ, which is again in agreement with the theoretical prediction. In summary, we have demonstrated that the tunable kink width critically determines the dependence of frictional force on the overlap length between the two intercalating nanofilaments. A length scale similar to λ arises in many other materials science contexts, such as shearing of double stranded DNA (refs 17,18).

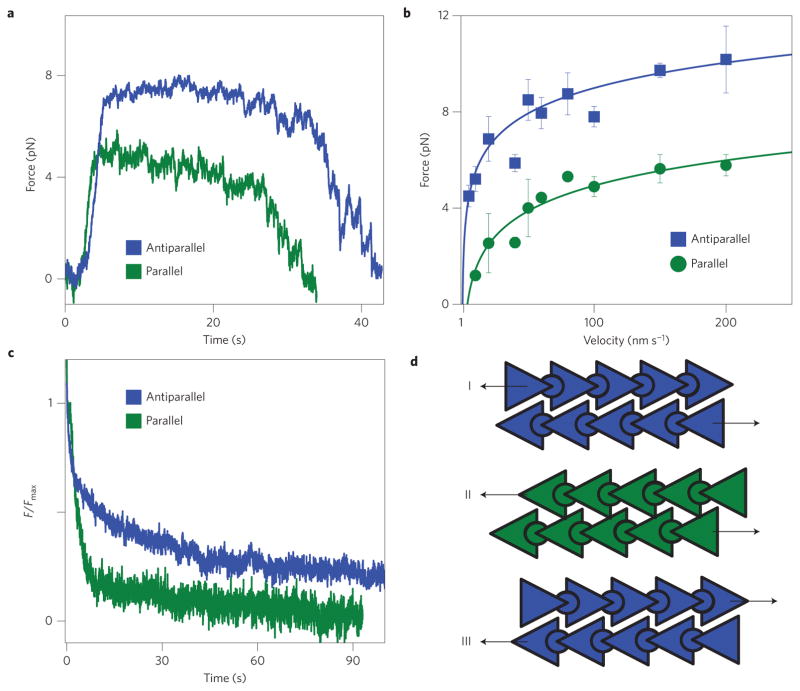

Previous experiments have uncovered directionally dependent friction in both biological and synthetic materials19–21. To investigate the directional dependence of interfilament sliding friction between polar actin filaments we have altered the experimental configuration by attaching beads to both ends of one filament (Supplementary Fig. 3). Using this configuration we find that Fmax for sliding antiparallel filaments is approximately twice as large as in filaments with parallel alignment (Fig. 3a,b). Whereas Fmax is different, the scaling of frictional force with velocity and filament overlap length is the same for both orientations, indicating that same physics describes sliding of both polar and anti-polar filaments. Furthermore, we also investigate stress relaxation on application of a step strain (Fig. 3c). For parallel orientation the applied stress quickly relaxes to a finite but small force. In contrast, for antiparallel orientation the applied stress relaxes on much longer timescales. These experiments indicate that the axial interaction potential between sliding F-actin filaments is polar; thus, sliding actin filaments can act as molecular ratchets (Fig. 3d).

Figure 3. Interfilament sliding friction depends on relative filament polarity.

a, Two profiles describing the time-dependent frictional force. The only difference is the relative filament polarity. b, The plateau force, Fmax, exhibits a pronounced directional dependence. Error bars indicate the s.e.m., with n = 2–13 (data points with n = 1 have no error bars). c, Relaxation of the force on application of a step strain. For parallel filaments the force quickly relaxes to a small but finite value. For antiparallel filaments the force relaxes on much longer timescales. d, Schematic representation of actin filaments that account for the directional dependence of sliding friction. Antiparallel and parallel arrangements correspond to schemes I and II, respectively. We are not able to measure friction for configuration III. All experiments were performed at a salt concentration of 400 mM KCl.

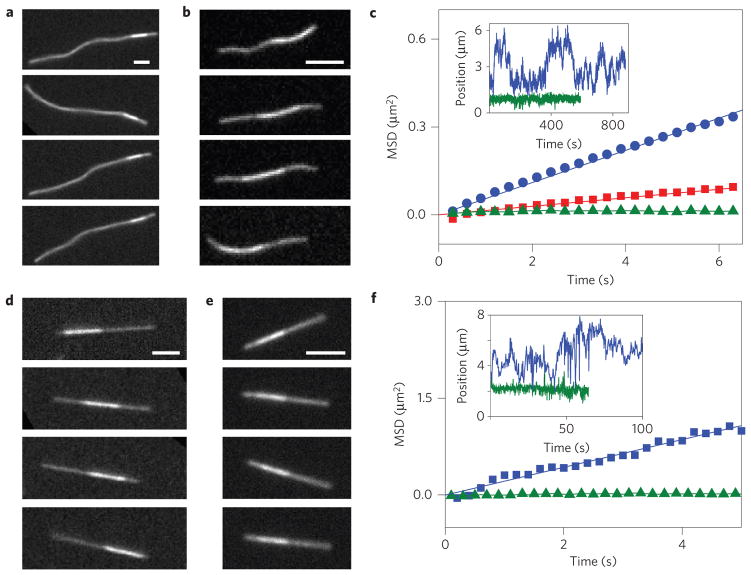

Armed with a basic understanding of filament sliding friction, we next devise practical methods to tune its magnitude. One possible method to accomplish this is by changing the filament structure. We decorated F-actin with a covalently attached PEG brush. In this system, friction was quantified by visualizing sliding dynamics of bundled filaments. Native F-actin bundles exhibited no thermally driven sliding, in agreement with our previous measurements (Fig. 4a). In contrast, PEG-coated F-actin formed bundles in which individual filaments freely slid past each other owing to thermal fluctuations (Fig. 4b and Supplementary Movie 3). To extract quantitative data, we measure the mean square displacement (MSD) of the relative position of the short filament with respect to the longer filament to which it is bound (Fig. 4c). The linear MSD curves are consistent with hydrodynamic coupling between PEG-coated filaments; the slope yields the diffusion of a bound filament, which is a factor of five smaller than that of an isolated filament22. It follows that the hydrodynamic friction coefficient of a bundled 5 μm-long filament is ~10−4 pN s nm−1. Pulling such a filament at 100 nm s−1 would result in a 10 fN force, which is three orders of magnitude smaller than the comparable forces measured for bare F-actin. This demonstrates how simple structural modifications greatly alter the sliding filament friction. We compare these results with those for another important biopolymer, a microtubule. Previous work has shown that, unlike F-actin, the sliding friction of a microtubule is weak and dominated by hydrodynamic interactions (Fig. 4d; ref. 23). Microtubule surfaces are coated with charged disordered aminoacid domains, known as e-hooks24. We hypothesized that these domains might act as an effective polyelectrolyte brush, screening molecular interactions and thus lowering sliding friction. To test this hypothesis we remove e-hooks with an appropriate protease. When treated in such a way, microtubule bundles exhibit no interfilament sliding, indicating a much higher sliding friction (Fig. 4e,f). Such observations agree with previous studies that have shown that brush-like surfaces can drastically lower friction coefficients25.

Figure 4. Filament surface structure controls the transition from solid to hydrodynamic friction.

a, Sequence of images illustrating the relative diffusion of a bundled pair of unmodified F-actin filaments. The brighter region, indicating the filament overlap area, is frozen at a specific location owing to the absence of any thermally induced filament sliding. b, F-actin filaments coated with a PEG polymer brush exhibit thermally driven sliding, owing to a significantly reduced frictional coupling (Supplementary Movie 3). c, For PEG-coated bundles of different lengths the mean square displacement (MSD) of the short filament with respect to the longer filament increases linearly with time, indicating a hydrodynamic coupling. Shown are MSDs of a 6-μm-long filament (red squares) and 3.7 μm-long filament (blue circles). Uncoated filaments (green triangles) exhibit a flat MSD. Inset: Relative position of a filament diffusing within the bundle for both coated (blue) and uncoated (green) F-actin. d, Untreated microtubule bundles exhibit diffusive sliding that is dominated by hydrodynamic coupling. e, Removing brush-like e-hooks from the microtubule surface leads to bundles that exhibit no sliding. f, MSDs of a bundle of microtubules (blue) compared with a bundle of subtilisin-treated microtubules (green). Inset: Relative position of a microtubule bundle for both untreated (blue) and subtilisin-treated microtubule (green). Scale bars, 3 μm.

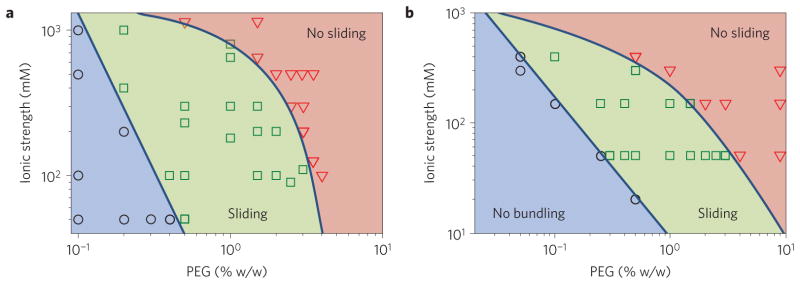

Alternatively, frictional coupling can be tuned by engineering lateral interfilament interactions. We examined how the sliding dynamics of three different filaments (F-actin, microtubules, bacterial flagella) depend on the strength of lateral filament attraction, which is controlled by the depletant concentration, and on the average filament separation, which is tuned by the ionic strength (Fig. 5). Microtubules and bacterial flagella exhibited two distinct dynamical states. For low depletant concentration (weak attraction) and low ionic strength the filaments have large lateral separations and freely slide past each other. Such dynamics indicates weak frictional coupling that is dominated by hydrodynamic interactions. Increasing depletant concentration or ionic strength above a critical threshold induces a sharp transition into a distinct dynamical state that exhibits no measurable sliding even after tens of minutes of observation time. The sliding dynamics of flagella and microtubules are remarkably similar to each other. In comparison, native F-actin filaments showed only a non-sliding state indicative of solid-like friction, for all parameters explored. The observation of non-sliding dynamics in three structurally diverse filaments suggests that solid-like frictional coupling is a common feature of biological filaments.

Figure 5. Sliding dynamics of microtubules and bacterial flagella.

a, Microtubule sliding dynamics depends on the depletant concentration and the suspension’s ionic strength. At low depletant concentration and ionic strength, filaments remain unbundled (blue circles). To induce bundle formation it is necessary to either increase the depletant concentration or decrease the electrostatic screening length. In this regime, bundles exhibit sliding dynamics (green squares). With increasing ionic strength or depletant concentration, sliding filaments undergo a sharp crossover into a state with no detectable sliding, indicating a stronger frictional coupling (red triangles). b, Straight bundled flagellar filaments exhibit sliding similar to that of microtubule bundles.

To summarize, the mechanical properties of composite filamentous bundles are determined not only by the rigidity of the constituent filaments but also by their interfilament interactions, such as the cohesion strength and sliding friction26. Therefore, quantitative models of composite bundle mechanics must account for interfilament sliding friction. We have demonstrated an experimental technique that enables the measurement of such forces. We directly measured frictional forces between chemically identical F-actin filaments, thus bridging the gap between the previously studied friction of sliding point-like contacts27,28 and 2D surfaces29–31. Combining such measurements with simulations and theoretical modelling, we have described the design principles required to engineer interfilament friction and thus tune the properties of frictionally interacting composite filamentous materials.

Methods

Actin and gelsolin were purified according to previously published protocols. Actin filaments were polymerized in high-salt buffer and subsequently stabilized with Alexa-488-phalloidin. Gelsolin was covalently coupled to 1μm carboxylic-coated silica beads by 1-ethyl-3-[3-dimethylaminopropyl]carbodiimide hydrochloride. All experiments were performed in a buffer suspension containing 20 mM phosphate at pH = 7.5, 300 mg ml−1 sucrose and either 200 mM or 400 mM KCl. Poly (ethylene glycol) (MW 20,000 Da) was used as a depletion agent at concentrations ranging between 20 and 35 mg ml−1, as indicated in the main text. An optical trap (1,064 nm) was time-shared between multiple positions using an acousto-optic Deflector. One bead was translated at a constant velocity while the force exerted on the other bead was measured using a back-focal-plane interferometry technique. Simultaneously, images of sliding F-actin filaments were acquired using fluorescence microscopy on a Nikon Eclipse Te2000-u microscope equipped with an Andor iKon-M charge-coupled detector. Sliding dynamics was visualized by confining a two-filament bundle in a quasi-2D microscope chamber, thus ensuring that filaments stay in focus. The surfaces were coated with a polyacrylamide brush, which suppresses adsorption of filaments. Bacterial flagella were isolated from Salmonella typhimurium strain SJW 605. The flagellin protein of these bacteria has a mutation that causes flagellar filaments to assume a straight shape. Microtubules were isolated following standard protocols.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge useful discussions with N. Upadhyaya, M. Hagan and R. Bruinsma. A.W., D.W. and W.S. were supported by National Science Foundation grants CMMI-1068566, NSF-MRI-0923057 and NSF-MRSEC-1206146. F.H. and Z.D. were supported by Department of Energy, Office of Basic Energy Sciences under Award DE-SC0010432TDD. V.V. acknowledges FOM and NWO for financial support. L.M. was supported by Harvard-NSF MRSEC and the MacArthur Foundation. We also acknowledge use of the Brandeis MRSEC optical microscopy facility (NSF-MRSEC-1206146).

Footnotes

Author contributions

A.W. and Z.D. conceived the experiments. A.W. measured actin sliding friction and performed computer simulations. F.H., A.W. and D.W. performed microtubule sliding experiments. W.S. performed flagella sliding dynamics. A.W.C.L. developed a preliminary theoretical model that explains the velocity dependence of sliding friction. L.M. and V.V. developed the theoretical model that explains the dependence of sliding friction on overlap length. A.W., V.V., L.M. and Z.D. wrote the manuscript. All authors revised the manuscript.

Supplementary information is available in the online version of the paper.

Competing financial interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.Vigolo B, et al. Macroscopic fibres and ribbons of oriented carbon nanotubes. Science. 2000;290:1331–1334. doi: 10.1126/science.290.5495.1331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sanchez T, Chen DTN, DeCamp SJ, Heymann M, Dogic Z. Spontaneous motion in hierarchically assembled active matter. Nature. 2012;491:431–434. doi: 10.1038/nature11591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kozlov AS, Baumgart J, Risler T, Versteegh CPC, Hudspeth AJ. Forces between clustered stereocilia minimize friction in the ear on a subnanometre scale. Nature. 2011;474:376–379. doi: 10.1038/nature10073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Claessens M, Bathe M, Frey E, Bausch AR. Actin-binding proteins sensitively mediate F-actin bundle stiffness. Nature Mater. 2006;5:748–753. doi: 10.1038/nmat1718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Heussinger C, Bathe M, Frey E. Statistical mechanics of semiflexible bundles of wormlike polymer chains. Phys Rev Lett. 2007;99:048101. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.99.048101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zimmerman SB, Minton AP. Macromolecular crowding—biochemical, biophysical and physiological consequences. Annu Rev Biophys Biomol Struct. 1993;22:27–65. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bb.22.060193.000331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rau DC, Lee B, Parsegian VA. Measurement of the repulsive force between poly-electrolyte molecules in ionic solution—hydration forces between parallel DNA double helices. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1984;81:2621–2625. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.9.2621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vanossi A, Manini N, Urbakh M, Zapperi S, Tosatti E. Colloquium: Modeling friction: From nanoscale to mesoscale. Rev Mod Phys. 2013;85:529–552. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Braun OM, Kivshar YS. Nonlinear dynamics of the Frenkel–Kontorova model. Phys Rep. 1998;306:1–108. doi: 10.1103/physrevb.43.1060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Merkel R, Nassoy P, Leung A, Ritchie K, Evans E. Energy landscapes of receptor–ligand bonds explored with dynamic force spectroscopy. Nature. 1999;397:50–53. doi: 10.1038/16219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gnecco E, et al. Velocity dependence of atomic friction. Phys Rev Lett. 2000;84:1172–1175. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.84.1172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Muser MH, Urbakh M, Robbins MO. In: Advances in Chemical Physics. Prigogine I, Rice SA, editors. Vol. 126. John Wiley; 2003. pp. 187–272. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Suda H. Origin of friction derived from rupture dynamics. Langmuir. 2001;17:6045–6047. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Holmes KC, Popp D, Gebhard W, Kabsch W. Atomic model of the actin filament. Nature. 1990;347:44–49. doi: 10.1038/347044a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kojima H, Ishijima A, Yanagida T. Direct measurement of stifness of single actin-filaments with and without topomyosin by in-vitro nanomanipulation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:12962–12966. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.26.12962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lau AWC, Prasad A, Dogic Z. Condensation of isolated semi-flexible filaments driven by depletion interactions. Europhys Lett. 2009;87:48006. [Google Scholar]

- 17.De Gennes PG. Maximum pull out force on DNA hybrids. C R Acad Sci IV. 2001;2:1505–1508. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hatch K, Danilowicz C, Coljee V, Prentiss M. Demonstration that the shear force required to separate short double-stranded DNA does not increase significantly with sequence length for sequences longer than 25 base pairs. Phys Rev E. 2008;78:011920. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevE.78.011920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bormuth V, Varga V, Howard J, Schaffer E. Protein friction limits diffusive and directed movements of kinesin motors on microtubules. Science. 2009;325:870–873. doi: 10.1126/science.1174923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Choi JS, et al. Friction anisotropy-driven domain imaging on exfoliated monolayer graphene. Science. 2011;333:607–610. doi: 10.1126/science.1207110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Forth S, Hsia K-C, Shimamoto Y, Kapoor TM. Asymmetric friction of nonmotor MAPs can lead to their directional motion in active microtubule networks. Cell. 2014;157:420–432. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.02.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li GL, Tang JX. Diffusion of actin filaments within a thin layer between two walls. Phys Rev E. 2004;69:061921. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevE.69.061921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sanchez T, Welch D, Nicastro D, Dogic Z. Cilia-like beating of active microtubule bundles. Science. 2011;333:456–459. doi: 10.1126/science.1203963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nogales E, Wolf SG, Downing KH. Structure of the αβ tubulin dimer by electron crystallography. Nature. 1998;391:199–203. doi: 10.1038/34465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Klein J, Kumacheva E, Mahalu D, Perahia D, Fetters LJ. Reduction of frictional forces between solid-surfaces bearing polymer brushes. Nature. 1994;370:634–636. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Akbulut M, Belman N, Golan Y, Israelachvili J. Frictional properties of confined nanorods. Adv Mater. 2006;18:2589–2592. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mate CM, McClelland GM, Erlandsson R, Chiang S. Atomic scale-friction of a tungsten tip on a graphite surface. Phys Rev Lett. 1987;59:1942–1945. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.59.1942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Luan BQ, Robbins MO. The breakdown of continuum models for mechanical contacts. Nature. 2005;435:929–932. doi: 10.1038/nature03700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yoshizawa H, Chen YL, Israelachvili J. Fundamental mechanism of interfacial friction. 1 Relation between adhesion and friction. J Phys Chem. 1993;97:4128–4140. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Van Alsten J, Granick S. Molecular tribometry of ultrathin liquid-films. Phys Rev Lett. 1988;61:2570–2573. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.61.2570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bohlein T, Mikhael J, Bechinger C. Observation of kinks and antikinks in colloidal monolayers driven across ordered surfaces. Nature Mater. 2012;11:126–130. doi: 10.1038/nmat3204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.