Abstract

Serotonin neurons in the dorsal and median raphe nuclei (DR and MR) are clustered into heterogeneous groups that give rise to topographically organized forebrain projections. However, a compelling definition of the key subgroups of serotonin neurons within these areas has remained elusive. In order to be functionally distinct, neurons must participate in distinct networks. Therefore we analyzed subregions of the DR and MR by their afferent input. Clustering methods and principal component analysis were applied to anterograde tract-tracing experiments in mouse available from the Allen Mouse Brain Connectivity Atlas. The results revealed a major break in the networks of the DR such that the caudal third of the DR was more similar in afferent innervation to the MR than it was to the rostral two thirds of the DR. The rostral part of the DR is associated with networks controlling motor and motivated behavior, while the caudal DR is more closely aligned with regions that regulate rhythmic hippocampal activity. Thus a major source of heterogeneity within the DR is inclusion of the caudal component, which may be more accurately viewed as a dorsal extension of the MR.

Keywords: Median Raphe, Serotonin, Dorsal Raphe, Mood, Depression, tract-tracing, RRID:nlx_146253, RRID:nlx_146253, RRID:nif-0000-30467, RRID:nif-0000-00362

Introduction

The majority of serotonin neurons that innervate the forebrain reside in the dorsal and median raphe nuclei (DR, MR). The DR in particular is a heterogeneous structure and in rodents can be divided into as many as nine subregions [reviewed by (Hale and Lowry, 2011)]. While these regions are primarily defined by cytoarchitecture, different groups of serotonin neurons also have topographically organized forebrain projections [reviewed by (Vasudeva et al., 2011; Waselus et al., 2011)]. As a consequence of this organization, serotonin release in the forebrain can be spatially controlled. Indeed, in different behavioral states there are region-dependent changes in extracellular serotonin and this can correlate with origin within different sets of serotonin neurons (Waselus et al., 2011).

The fact that subsets of serotonin neurons control serotonin release in selective forebrain locations raises the likelihood that these neurons have different functions in modifying behavior. The concept of functional diversity of serotonin neurons is attractive because it provides a potential explanation for how a single neurotransmitter, serotonin, is associated with multiple psychopathologies. That is, impaired function of one group of serotonin neurons may give rise to depression while impairment of another could generate obsessive-compulsive disorder, etc. Yet the identity of meaningful groups of serotonin neurons remains poorly defined.

More specifically, many subregions of the MR and DR have been identified but it is not clear that each of these subregions is equally unique and unrelated to all other subregions. Furthermore, the definition of subregions is most commonly based on cytoarchitecture, which may have an indirect and complicated relationship to function. In contrast, network connectivity is a major determinant of function(Sporns, 2011). Therefore, in this study an informatics approach was applied to systematically examine the organization of subregions within the DR and MR by identifying areas that received similar sets of afferent innervation. Patterns of afferent innervation were analyzed using a publically available database of anterograde-tract tracing experiments (Oh et al., 2014). This approach would reveal not only what regions differed from others, but also importantly, the extent to which they differed.

Methods

The analysis was designed to compare different subregions of the DR and MR by virtue of afferent innervation, and to identify subregions that were similar in the afferents they received. To do this, the afferent termination pattern arising from many different brain regions was studied using anterograde tract-tracing experiments available from the Allen Mouse Brain Connectively Atlas (Website: ©2014 Allen Institute for Brain Science. Allen Mouse Brain Connectivity Atlas [Internet]. Available from: http://connectivity.brain-map.org/; RRID:nlx_146253) (Oh et al., 2014). This was an informatics analysis that did not involve additional mice or protocol approval at Boston Children’s Hospital.

To identify anterograde tract-tracing cases that resulted in innervation of the MR or DR, the Mouse Brain Connectivity Atlas was searched either using the DR or MR as the target structure, or using a spatial search using the same areas. Cases were selected from among these to represent transport from as many distinct origins as possible. When injection cases in neighboring regions were selected, pairs of cases with the best transport and minimal overlap with each other were selected. Overlap was evaluated by visualizing the serial section images of the injection site available for each candidate case side by side. In addition, the pattern of afferent termination in the DR and MR examined for similarities and differences. Replicates, or multiple injections in the same target, would not necessarily strengthen the analysis, therefore when replicates were available, a single representative case was selected that had the best transport to the DR/MR.

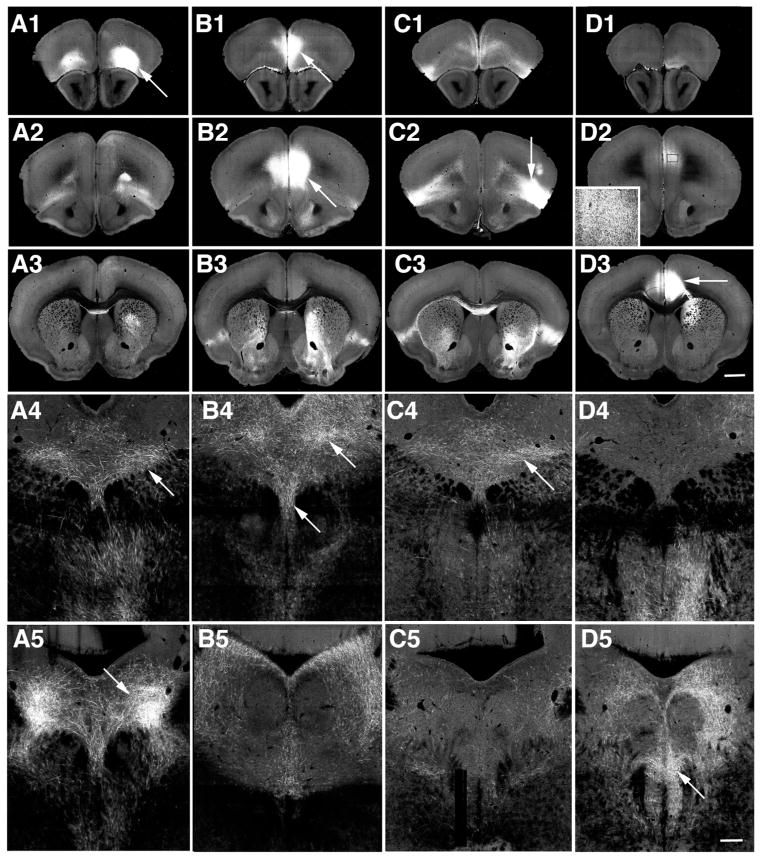

For example, injection sites primarily located in the orbital, prelimbic, agranular insular and anterior cingulate cortices often impinged upon one another as secondary targets (Table 1, Fig. 1). However examination of the injection sites on serial sections revealed that the individual injections covered largely distinct locations. In addition, the overall patterns of afferent innervation at the level of middle and caudal DR appeared distinct (Fig. 1A4–D5), suggesting they arose from different sources. In some cases projections from neighboring injection sites appeared similar, such as in the case of the substantia nigra and ventral tegmental area, but both these areas are known to provide afferents to the DR (Vertes and Linley, 2008) and the injection sites did not appear to overlap, therefore both of these injection sites were included. That is, every case that had an injection site placed in a unique location or exhibited a projection pattern distinct from those arising from nearby injections sites was included.

Table 1.

Cases used from the Allen Mouse Brain Connectivity Atlas (Website: 2014 Allen Institute for Brain Science. Allen Mouse Brain Connectivity Atlas [Internet]. Available from: http://connectivity.brain-map.org/) (Oh et al., 2014). Serial section images through the entire brain and ancillary information regarding each case can be accessed by searching for the listed case number. The last two cases were used for analysis of common targets.

| Experiment | Target Structure | Secondary Structures | Transgenic Line | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 156741826 | Orbital area, lateral part (ORBl) | AI (3.2%) | Rbp4-Cre_KL100 | |

| Similar: 168164972 | Orbital area, lateral part (ORBl) | ORBvl (32.9%) | A930038C07Rik-Tg1-Cre | ||

| These two injection sites result in similar axon distribution in the DR/MR. | Probable source: ORBl | ||||

| 2 | 263106036 | Prelimbic area (PL) | ACA (4.8%), ILA (29.2%), ORBm (19.8%) | Rbp4-Cre_KL100 | |

| Similar: 157711748 | Prelimbic area (PL) | ILA (20.4%), ORBm (29.4%) | C57BL/6J | ||

| These two injection sites result in similar axon pattern distribution in the MR/DR although 263106036 has stronger fluorescence. The ILA and ORBm are minor sources to the DR/MR and their contribution cannot be ruled out. | Probable source: PL ≫ ILA, ORBm | ||||

| 3 | 166153483 | Agranular insula (AI), (dorsal/ventral) | MO (9.9%) | Rbp4-Cre_KL100 | |

| Similar: 112596790 | Agranular insula (AI) | Gu (37.6%) | C57BL/6J | ||

| These two injection sites result in similar axon distribution in the DR/MR. | Probable source: AI | ||||

| 4 | 161458737 | Anterior cingulate (ACA) (dorsal/ventral) | ILA (5.4%) | Rbp4-Cre_KL100 | |

| Similar: 125833030 | Anterior cingulate, dorsal (ACAd) | MO (9.9%) | Rbp4-Cre_KL100 | ||

| These two injection sites result in similar axon distribution in the DR/MR. | Probable source: ACA | ||||

| 5 | 166054929 | Retrosplenial area (RSP), (dorsal) | RSPagl (1.1%) | Rbp4-Cre_KL100 | |

| No adjacent areas are notable afferents. | Probable source: RSP | ||||

| 6 | 168615344 | Nucleus accumbens (ACB) | DP (2.4%), CP (10.4%), LS (3.3%), ILA (5.6%), TT (2.7%) | Drd1a-Cre | |

| Similar: 167904966 | Nucleus accumbens (ACB) | CP (3.5%), SI (30.2%), NDB (4.7%) | Drd2-Cre_ER44 | ||

| The ACB is a known major source while the CP is a minor source. | Probable source: ACB≫>CP | ||||

| 7 | 157659671 | Olfactory tubercle (OT) | SI (30.5%), MA, CP, NDB (12.2%), ACB (10%) | C57BL/6J | |

| SI is a major source of afferents to the DR/MR. The OT and NDB may be minor sources in mice (Ogawa et al., 2014). Case168615344 ACB appears qualitatively distinct. | Probable source: SI > OT > NDB > ACB | ||||

| 8 | 159650350 | Anterior amygdalar area (AAA) | NLOT, FS (7%), GPe (2.7%), CEA, OT (2.1%), CP (9.7%), MEAad, LPO (1.3%), BMA, MA (10.3%), SSp (2.2%), SI (39.2%) | C57BL/6J | |

| This injection site is positioned caudal to OT targeted 157659671 and identifies axons in a different pattern. Both the AAA and SI are likely potential sources (Ogawa et al., 2014). | Probable source: AAA = SI | ||||

| 9 | 181890477 | Central amygdalar nucleus (CEA) | LHA (2.7%), SI (12.1%), GPi, BMA (2.2%), MEA (27.5%), BLA (1.9%) | Etv1-CreERT2 | |

| The CEA is a major source of afferents while the BLA BMA and MEA are minor sources. OT and AAA injection cases appear qualitatively different, suggesting the SI is not a likely origin. | Probable source: CEA | ||||

| 10 | 100141597 | Medial septal nucleus (MS) | LS (9.8%), MEPO (3.5%), LPO (7%) | C57BL/6J | |

| LS and MEPO are minor sources of afferents to MR/DR. LPO injections yield a different pattern represented by another case (146470726). | Probable source: MS | ||||

| 11 | 120280191 | Medial preoptic area (MPO) | BST (24%), ACA (6.6%), AHN (8.8%), MPN (15.8%), LS (2.4%), PVH (2.5%) | C57BL/6J | |

| Similar: 158315810 | Medial preoptic area (MPO) | BST (34%), AVP (3.2%), PS (1%), AHN, MPN (8.9%), LPO (8.2%) | C57BL/6J | ||

| Similar: 126116142 | Medial preoptic nucleus (MPN) | BST (13.9%), MPO (21.8%), AHN (33.9%), LHA (3.9%) | C57BL/6J | ||

| Most injections in the MPO, BST and the AHN overlap with each other to some degree. In addition, they are all potential sources of afferents to the MR/DR. | Probable sources: MPO, MPN > BST>AHN | ||||

| 12 | 146470726 | Lateral preoptic area (LPO) | SI (6.7%), BST (16.4%), MPO (4.6%), ACB (8.9%), LS (3.6%), ADP (1.5%), MS (9.9%), PS (2.4%) | C57BL/6J | |

| Qualitatively different from the MS and MPO projections. Contribution of the SI, BST and ACB cannot be excluded. | Probable source: LPO > BST> ACB > SI | ||||

| 13 | 114046440 | Lateral hypothalamic area (LHA) | MO (1.1%), ZI (22.8%), VM (6.6%), VAL | C57BL/6J | |

| Injections centered on the LHA involve the ZI to some extent and vice versa. Both areas are major afferents. This injection site is adjacent but positioned medial, ventral and rostral to the ZI injection 126190743. | Probable source: LHA > ZI | ||||

| 14 | 126190743 | Zona incerta (ZI) | STN (12.1%), VM (2.7%), LHA (6.8%), VPLpc, PSTN (1.8%), FF | C57BL/6J | |

| Similar: 305379705 | Zona incerta (ZI) | VM, LHA (43%), PSTN (2.3%) | slc32a1-IRES-Cre | ||

| The ZI itself is a known major source of afferent while the VM and FF are minor sources. Replicated by 305379705 suggesting the pathway is GABAergic. | Probable source: ZI≫LHA | ||||

| 15 | 120875111 | Paraventricular nucleus of the thalamus (PVT) | PF (3.2%), MH (3.1%), LH (15.5%) | C57BL/6J | |

| The LH is the major afferent to the MR/DR although a few cells in the MH, fewer in the PF, and fewer still in the PVT could contribute to this projection (Ogawa et al., 2014). | Probable sources: LH≫MH, PF, PVT | ||||

| 16 | 158314987 | Supramammillary nucleus (SUM) lateral and medial | LHA (4.4%), PH (24%), PM (2.1%), SNr (0.9%), MM (14%), VTA (13.6%) | C57BL/6J | |

| Different: 175374275 | Posterior hypothalamic nucleus (PH) | RSPv (1.7%), CAI VM (2.9%), SPFm (2.6%), MD (3.1%), SMT (3.0%), PVT (1.1%), RE (8.5%), RH (2.1%), CM (3.9%), DMH (20.2%), TMd, PMd, LHA (2.7%), ZI (2.2%) | C57BL/6J | ||

| Injections in the VTA yield a different pattern represented by 127867804. PH is a potential contributor, but injections there innervate predominantly the vlPAG. Both MM and SUM are known afferents to the MR (Ogawa et al., 2014; Vertes and Linley, 2008). | Probable source: SUM>MM≫PH | ||||

| 17 | 158914182 | Substantia nigra compacta and reticulata (SNc, SNr) | RSP (1.8%), VTA (9.5%), RR (7.8%), MRetN (21%), RN (5.9%), | C57BL/6J | |

| Different: 120811946 | Midbrain Reticular Nucleus | Red Nucleus (RN) (28%), ZI | C57BL/6J | ||

| The SNc and SNr both provide afferents with the SNc predominating (Ogawa et al., 2014). The VTA is possible source but little overlap with the other VTA injection. The MRetN/RN injection is very sparse over the DR and favors the lPAG. | Probable source: SNc > SNr ≫ VTA | ||||

| 18 | 127867804 | Ventral tegmental area (VTA) | LHA (2.1%), RSPv (4.2%), PH (7.2%), IPN, IF, SPF, MRetN (28.2%), SNc (1.2%) | Erbb4-2A-CreERT2 | |

| VTA is a known major afferent (Ogawa et al., 2014), yielding a different pattern of afferents compared to injections in RSP, MRetN, PH and IPN. | Probable source: VTA | ||||

| 19 | 171019710 | Interpeduncular nucleus (IPN) | CLI (10.4%), IF (7.4%), EW (2.1%), RL (1.4%), VTA (11.5%), MR | Slc32a1-IRES-Cre | |

| IPN is a major source of afferents, however contributions of the CLI, VTA and IF are possible. | Probable source: IPN>VTA, CLI, IF | ||||

| 20 | 160081484 | Gigantocellular reticular nucleus (GRN) | RO, PGRN (2.2%), RM (3.3%), MARN (16.4%) | Slc6a5-Cre_KF109 | |

| Includes ventromedial medullary sources of afferent to the DR including the RM. | Probable source: GRN>RM | ||||

| 21 | 175142304 | Paragigantocellular reticular nucleus, lateral part (PGRNl) | GRN (14.2%), IRN (2.6%), MARN (11.7%), AMB (3.8%), IO (8.8%), LRN (8.2%) | C57BL/6J | |

| Neurons in the ventrolateral medulla that project to the DR are located in the PGRN and LRN. Pattern of innervation different from the midline injection 160081484. | Probable source: PGRN>LRN | ||||

| 22 | 114155190 | Dorsal nucleus raphe (DR) | Slc6a4-CreERT2-EZ13 | ||

| 23 | 156929391 | Superior central nucleus raphe (MR) | CLI, TRN, PRNr | C57BL/6J | |

Abbreviations used in alphabetical order, with the addition of a, c, p, m, l or d designating anterior, central, posterior, medial, lateral or dorsal parts, respectively:

AAA, anterior amygdalar area

ACA, anterior cingulate area

ACB, nucleus accumbens,

ADP, anterodorsal preoptic nuclues

AHN, anterior hypothalamic nucleus

AI, Agranular insular area

AMB, nucleus ambiguus

BLA, basolateral amygdalar nucleus

BMA, basomedial amygdalar nucleus,

BST, bed nuclei of the stria terminalis

CEA, central amygdalar nucleus

CLI, Central linear nucleus raphe

CM, central medial nucleus of the thalamus

CP, Caudoputamen

DMH, dorsomedial nucleus of the hypothalamus

DP, Dorsal peduncular area

DR, dorsal raphe nucleus

EW, Edinger-Westphal nuclues

FF, Fields of Forel

FS, Fundus of striatum

GPe, Globus Pallidus, external segement

GPi, Globus Pallidus, Internal segment

GRN, Gigantocellular reticular nucleus

GU, gustatory areas

IF, interfascicular nucleus raphe

ILA, Infralimbic area

IO, Inferior olivary complex

IPN, interpeduncular nucleus

IRN, intermediate reticular nucleus

LH, lateral habenula

LHA, Lateral hypothalamic area

LPO, lateral preoptic area

LRNm, lateral reticular nucleus, magnocellular part

LS, Lateral septal nucleus

MA, Magnocellular nucleus

MARN, Magnocellular reticular nucleus

MD, mediodorsal nucleus of thalamus

MEA, Medial amgdalar nucleus

MEAad, Medial amgdalar nucleus, anterodorsal part

MEPO, Median preoptic nuclues

MH, Medial Habenula

MM, Medial mammillary nucleus

MOp, Primary motor area

MPN, Medial preoptic nuclues

MPO, medial preoptic area

MRetN, Midbrain reticular nucleus

MRN, median raphe nucleus

MS, medial septal nucleus

NDB, Diagonal band nucleus

NLOT, Nucleus of the lateral olfactory tract

ORB, orbital area

OT olfactory tuberacle

PAG, periaqueductal grey

PF, parafascicular nucleus of the thalamus

PGRN, Paragigantocellular reticular nucleus

PH, Posterior hypothalamic nucleus

PL, Prelimbic area

PMd, Dorsal premammillary nucleus

PRNr, Pontine reticular nucleus

PS, Parastrial nucleus

PSTN, Parasubthalamic nucleus

PVH, Paraventricular hypothalamic nucleus

PVT, Paraventricular nucleus of the thalamus

RE, nucleus of reunions

RH, rhomboid nucleus

RL, Rostral linear nucleus raphe

RM, Nucleus raphe magnus

RN, Red nucleus

RO, Nucleus raphe obscurus

RR, Midbrain reticular nucleus, retrorubral area

RSPagl, Retrosplenial area, lateral agranular part

RSP, Retrosplenial area

SI, Substantia innominate

SMT, submedial nucleus of the thalamus

SN, Substantia nigra

SPF, Subparafasicular nucleus

SSp-ll, Primary somatosensory area, lower limb

SSp-ul, Primary somatosensory area, upper limb

STN, Subthalamic nucleus

SUM, Supramammillary nucleus

TMd, tuberomammailary nucleus, dorsal part

TRN, Tegmental reticular nucleus

TTd, Taenia tecta, dorsal part

VAL, Ventral anterior-lateral complex of the thalamus

VM, Ventral medial nucleus of the thalamus

VPLpc, Ventral posterior lateral nucleus of the thalamus, parvicellular part

VTA, ventral tegmental area

ZI, zona incerta

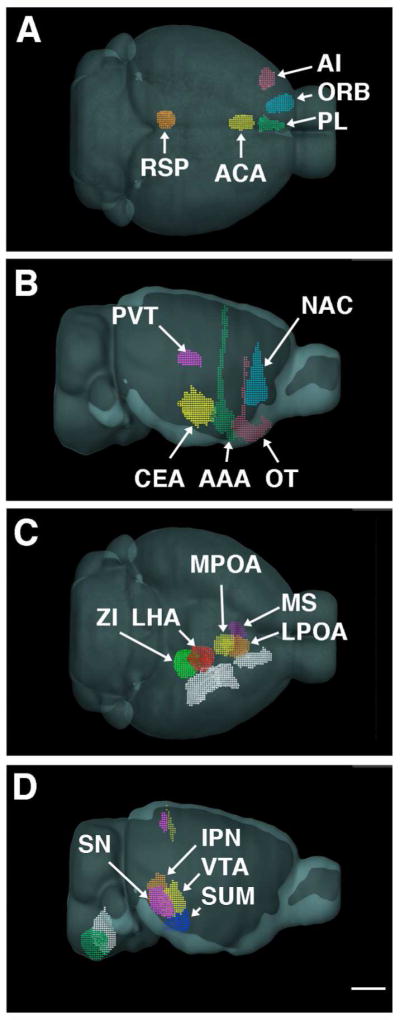

Figure 1.

Examples of selected cases from the Allen Brain Connectivity Atlas (Oh et al., 2014). Injection sites are centered on orbital (A), prelimbic (B), agranular insular (C) and anterior cingulate cortices (D). Three levels (panels 1–3) shown from approximately 20 serial sections available that span these regions as well as images of the corresponding projections to the DR and MR (panels 4,5). Each injection site (arrows, panels 1–3) captures a distinct domain. D2, boxed region shown at higher magnification in inset, shows fluorescence in the prelimbic cortex corresponds to axons and is not an extension of the injection site. Within the middle (panels 4) or caudal DR (panels 5) axons are detected in largely different patterns for each injection case. Panels 1–3 same magnification bar in D3 = 150. Panels 4–5 same magnification, bar in D5 = 150. Image credit: Allen Institute for Brain Science.

Cases were identified in almost all the known major sources of afferents to the MR and DR, however injection sites in some areas that innervate the DR or MR were not available within the database. For example, no cases with suitable transport originating the parabraichial nucleus or locus coeruleus were identified. Cases where the injection site impinged on 10% or more of the area defined as the MR or DR were excluded because the injection site itself would be confounded with the projection pattern. This occurred with injections in the periaqueductal gray. Overall, a dataset of twenty-one cases targeting the cortex, basal forebrain, hypothalamus, thalamus and medulla was assembled (Table 1, Figure 2). Figure 2 shows schematic views of the location of the injection sites generated with the Allen Institute’s “Brain Explorer 2” software (RRID:nif-0000-00362) and illustrates that the 21 cases originated in distinct regions that spanned the neuroaxis.

Figure 2.

Schematic views of the injection sites used. A. Cortical injection sites from a dorsal vantage point show PL (green) near the midline. ORB (blue) and AI (pink) are more lateral. The ACA (yellow) and RSP (orange) injection sites are caudal. B. Lateral view shows the NAC (blue), and from rostral to caudal, the OT (purple), AAA (green) and CEA (yellow) injection sites, with the PVT (pink) injection site located dorsally. C. View from the ventral aspect of the brain shows MS injection site (purple) is medial to the LPO (orange) which lies rostral to MPO targeted injection site (yellow). The LHA injection site (red) is adjacent to the ZI injection site (green) on it’s ventral, rostral and medial aspect. Lateral to all these injection sites are those targeting the CEA, AAA, and OT injections (all depicted in white). D. SN injection (pink) is lateral to the IPN injection site (orange) on the midline. Both of these are caudal to the injection encompassing much of the VTA (yellow). The injection in the SUM (blue) is further rostral and ventral. In the medulla, the GRN injection site is on the midline (white). Relative to this, the PGRNl positioned both caudal and lateral (green). All panels same scale bar = 2 mm

Table 1 lists the 21 injection cases selected for analysis, plus two cases targeting the DR and MR that were used for analysis of common targets. Available in Table 1 are the primary and secondary structures impacted by the injection site identified by the manual annotation process at the Allen Institute. The percent of the injection site that distributed to each secondary target is also noted, if that number was available under the ‘quantified injection summary’, which is generated through the informatics pipeline at the Allen Institute. Comparator cases (listed as ‘similar’ or ‘different’) as well as the interpreted probable source or sources of the projection are also given in Table 1. The probable source was determined by considering the known afferent sources to the MR or DR as established in the rat (Peyron et al., 1998; Vertes and Linley, 2008) and mouse (Ogawa et al., 2014; Pollak Dorocic et al., 2014; Weissbourd et al., 2014), in conjunction with evaluation of the original images of the injections sites in the selected and comparator cases, as well as their pattern of termination within the MR and DR. In most cases the probably source corresponded to the target structure with exception of the olfactory tubercle and paraventricular nucleus of the thalamus. These areas themselves are minor afferents to the MR and DR while neighboring substantia innominata and lateral habenula, also encompassed by those injection sites, are major afferents. In several cases, participation of secondary structures could not be ruled out, which should be kept in mind while considering the functional role of the networks.

About half of the selected cases utilized recombinant adeno-associated virus (rAAV) tracer expressing enhanced GFP (EGFP) under control of a human synapsin 1 promoter in C57BL/6J mice. The remainder used a similar virus where expression of EGFP was Cre-dependent in combination with a transgenic mouse expressing Cre in a subset of neurons (Table 1). Characterization of the viral methods suggests the rAAV-tract tracing performs similarly to biotinylated dextran amine (BDA) and is highly reproducible and afferent trajectory from pairs of similar injections have very high correlations (r = 0.90) ((Wang et al., 2014) Oh et al., 2014).

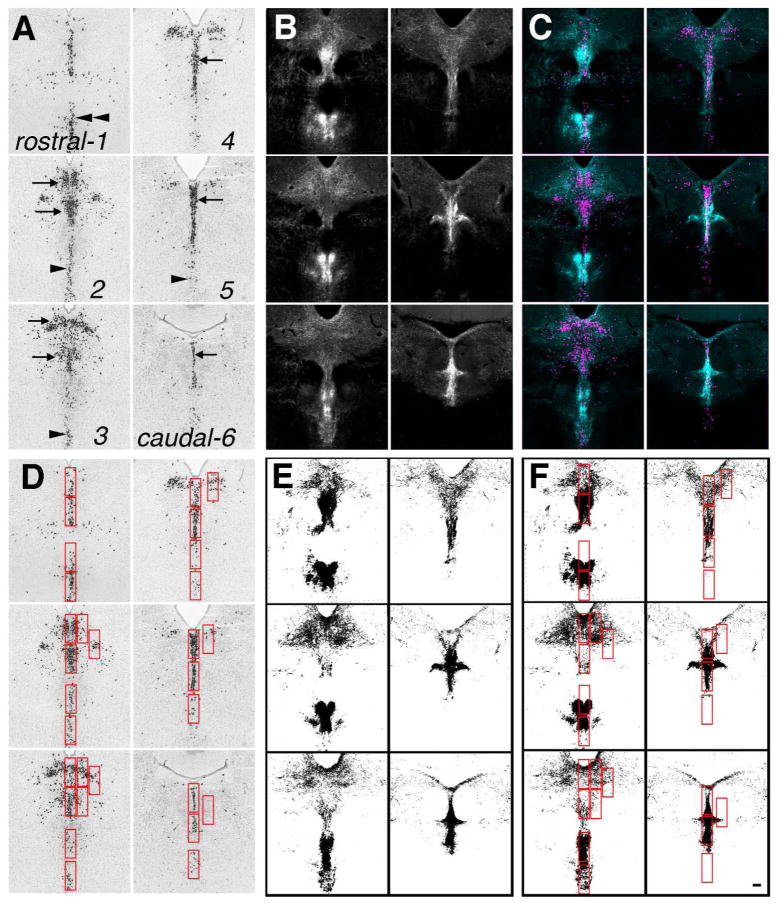

To analyze the pattern of afferent innervation to the DR and MR that arose from these twenty-one different cases, a template spanning the rostrocaudal extent of the DR was created using of six images of in situ hybridizations for mRNA encoding tryptophan hydroxylase-2, the rate-limiting enzyme for serotonin synthesis, taken from the Allen Mouse Brain Atlas (Fig. 3A) (Website: ©2014 Allen Institute for Brain Science. Allen Mouse Brain Atlas [Internet]. Available from: http://mouse.brain-map.org/; RRID:nlx_146253) (Lein et al., 2007). These images also included areas of the median raphe nucleus (MR) and the caudal linear nucleus (CLI). From each tract-tracing case, six image planes were selected to match the serotonin template. Typically this included every-other available image of the projection case (Fig. 3B). Using transparent layers in Adobe Photoshop, images of the projection case were aligned to the serotonin template. As fiduciaries, the base of the aqueduct and the interfasicular region were used. After alignment, the images were pseudo-colored and merged to check the accuracy of the alignment using NIH Image J software (available at http://fiji.sc/Fiji; RRID:nif-0000-30467) (Fig. 3C).

Figure 3.

Overview of data collection. A. Using images of TPH2 in situ hybridization from the Allen Mouse Brain Atlas (Website: ©2014 Allen Institute for Brain Science. Allen Mouse Brain Atlas [Internet]. Available from: http://mouse.brain-map.org/) (Lein et al., 2007) six levels through the DR and MR were selected from rostral (1) to caudal (6) to generate a template. These images included serotonin neurons located in the caudal linear nucleus (double arrowheads), DR (arrows) and MR (single arrowheads). B. Equivalent levels from each selected tract-tracing case from the Allen Mouse Brain Connectivity Atlas (Oh et al., 2014) were aligned to the template. This example shows the projection from the interpeduncular nucleus. C. Alignment was checked by pseudocoloring and merging the template and the projection case. D. Regions of interest (ROIs, red boxes) were selected using the template of serotonin neurons. E. A threshold was applied to each projection case. F. Identical ROIs were transferred to the threshold image, and particles were measured within each ROI. All panels at same magnification bar = 150 um. Image credit: Allen Institute for Brain Science.

Using the serotonin-neuron template, 30 regions of interest (ROI) were identified that either included a cluster of serotonin neurons in the DR, MR, CLI or areas lateral to these areas (Fig. 3D). For lateral areas, ROIs were placed on the side where the innervation was heaviest, if there was asymmetry in the innervation. The ROIs were selected with a bounding rectangle of the same size (sampling the same unit area) from each ROI. The size of the bounding rectangle was selected to be forgiving of minor displacements caused by variance in image alignment.

Using NIH Image J software, a manually set threshold was applied to the images of each projection case (Fig. 3E). The threshold was selected to include projection fibers but exclude random noise or non-specific signal. Using a macro, ROIs defined using the template were transferred to each projection case in turn and, using ‘measure-analyze particles’, the number of supra-threshold pixels was measured within each ROI (Fig. 3F). To focus on the distribution pattern of fibers rather then the overall magnitude of each projection, the number of pixels within each ROI was normalized to the total number of sampled pixels within all 30 ROIs for each case. Thus the strength of individual projection was not a factor rather the relative distribution of the projection within the sampled areas was analyzed.

The relative density of projections in each ROI for each projection yielded a data matrix of 21×30 values (21 projection cases by 30 ROIs). This matrix was subjected to unsupervised hierarchical clustering using Ward’s method. When clustering similar ROIs, the data were standardized by z-score by ROI. In Matlab, Ward’s method uses Euclidean distance as the multidimensional distance metric. As hierarchical clustering is bottom-up process, we then used K-means clustering, a top down or agglomerative process to confirm the groupings. Silhouette analysis of the resultant groups was used to evaluate the quality of the clustering.

In addition, the data matrix was subjected to principal component analysis. The projection sites with significant correlation to each principal component were determined. Clustering, Silhouette analysis, principal component analysis, Scree plot and correlations were done using Matlab.

Subsequently we asked which projection cases produced similar patterns of afferent innervation. To do this, we transposed the data matrix and did hierarchical and agglomerative sorting again. We also determined, by direct examination of the data matrix, the ROI that received the highest percent of innervation for each projection case.

For the two major groups of projection cases that were identified, we then sought to determine if there were any areas that were commonly targeted by members of those groups, i.e. ‘small-world’ partners. For example, the medial septum and supramammillary nucleus innervate the median raphe. These three areas are known to have a common target: the hippocampus. In order to identify common targets, the ‘projection summary details’ were downloaded from the Allen Mouse Brain Connectivity Atlas. For each individual projection case, these data describe the magnitude of innervation found in all other brain regions, i.e. volume of segmented pixels within all target regions. These data and the results depicted in Figure 8 depend on informatics processing at the Allen Institute including alignment to a 3D reference atlas (Oh et al., 2014). The accuracy of this alignment process has been quantitatively examined (Oh et al., 2014), however the results were also checked by visualizing the original images. For analysis of the quantitative results reported by the Allen Institute, the magnitude of innervation was converted to percentages by normalizing by the overall size of the projection within ‘grey’ matter. The target regions were sorted from highest to lowest, by the average percent of the projection they received from all the grouped cases. The premise was that target regions that receive the highest amount of projections could be potentially relevant network partners. For this analysis, two additional projection cases were included, one that included the rostral part of the DR, and another that was centered in the MR (Table). The top three projection targets were graphically represented in Fig. 8 by drawing lines from projection origin to target where the weight of the line was proportional to the percent of the innervation that projected to that area, rounded to the nearest 5%. For example, a 1 pt line was used to show a projection that represented between 2.5–7.4% of the total projection, a 2 pt line was used to show a 7.5–12.4% projection, a 3 pt line for 12.5–17.4%, up to a 10 pt line for 47.5–52.4%. Projections that accounted for less then 2.5% of the total projection were not depicted. Projection targets that were the same as the site of origin (recurrent collateral projections, such as from the ACB to the ACB) were excluded from the analysis.

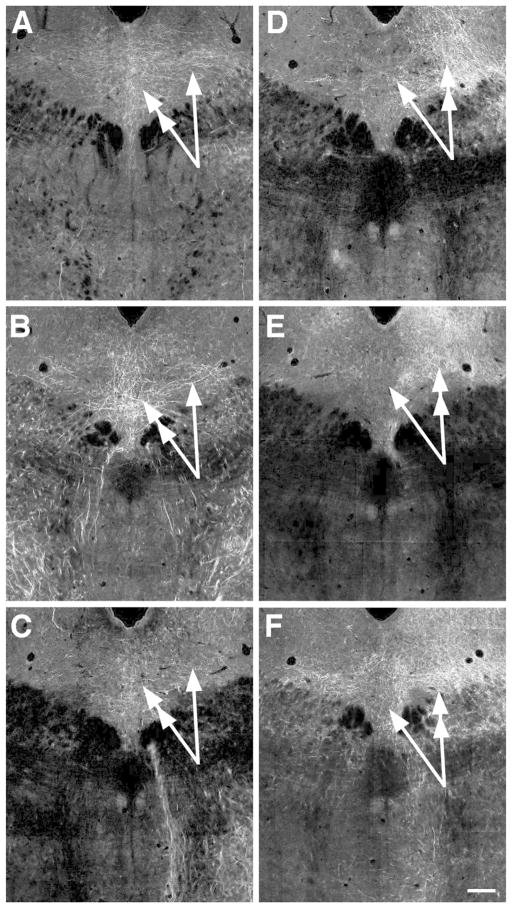

Figure 8.

Projections that had the highest differential of innervation between midline and lateral parts of the rostral DR. Projections from the substantial nigra reticulata (A), gigantocellular reticular nucleus (B) and ventral tegmental area (C) all prefer the midline (double-headed arrows) over lateral locations (single-headed arrows). Conversely projections from the central nucleus of the amygdala (D), medial preoptic area (E) and lateral hypothalamic area (F), have more fibers lateral (double-headed arrows) then on the midline (single-headed arrows). Image credit: Allen Institute for Brain Science. All images same scale bar in F = 150 um.

For figure presentation, images were manipulated using Adobe Photoshop for brightness and contrast using ‘image-adjust-curves’. In addition, when visible, seam artifacts between tiles were removed using a ‘rubber stamp’ tool.

Results

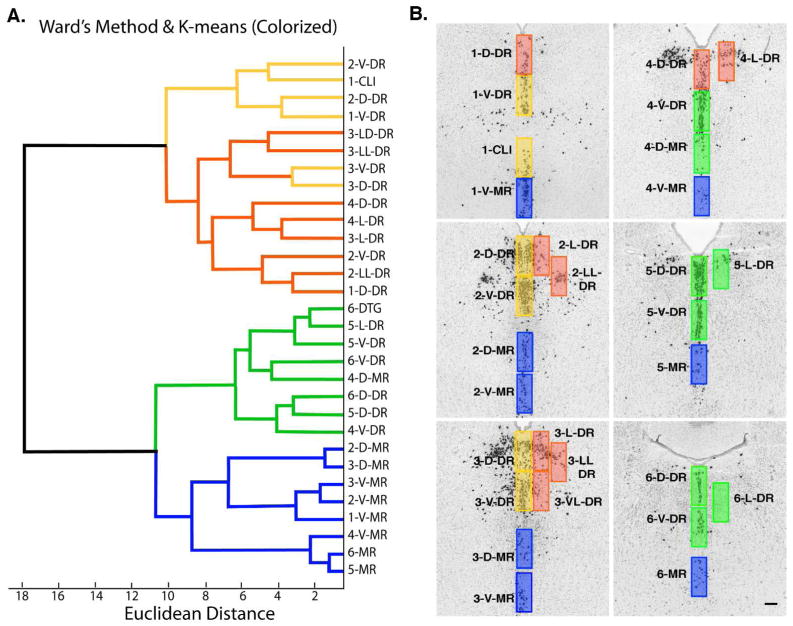

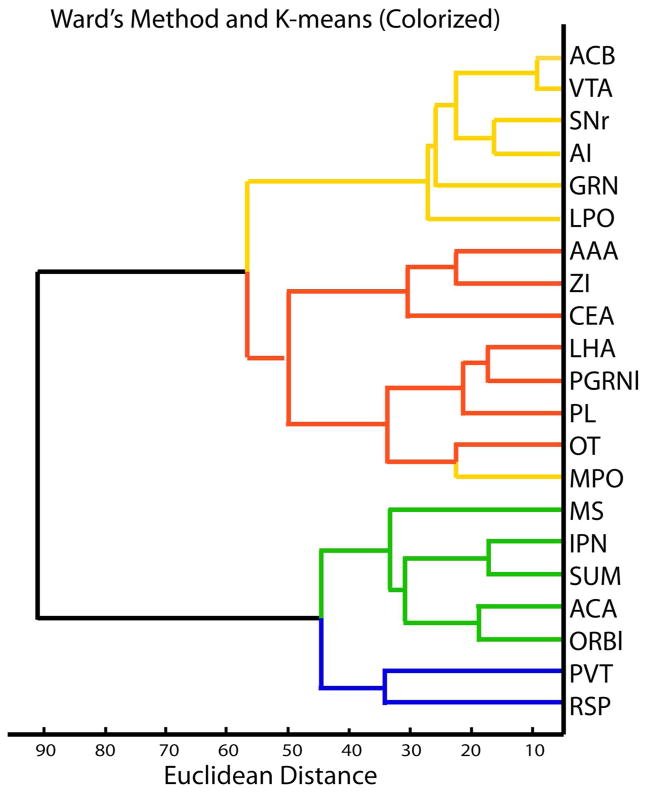

First we examined how ROIs representing different subregions of the DR, MR and nearby areas grouped with respect to afferent innervation by using heirarchical clustering with Ward’s method. The dendrogram showed two major branches, one of which contained all of the rostral DR while the other included the caudal DR and MR (Fig. 4). This pattern revealed that the caudal DR was more similar in afferent input to the MR then it was to the remaining rostral regions of the DR. Subsequent branching of the dendrogram suggested the caudal DR and MR could be further distinguished from each other. Subgroups within rostral DR were less pronounced, with longer lines connecting individual regions and groups of regions together indicating more heterogeneity existed in these areas.

Figure 4.

Cluster analysis shows the caudal DR is more similar to the MR then the remaining rostral DR. A. Dendrogram generated using Ward’s method, and colorized according to K-means. The dendrogram has two major branches one involving all of the rostral DR (yellow/red), the other includes the MR (blue) and caudal DR (green). Further subgroups defined with K-means divide the rostral DR largely by midline (yellow) and lateral (red) ROIs, and divides the caudal DR (green) from MR (blue). B. Map of serotonin neurons with ROIs colorized by K-means-defined groups. All panels at same magnification bar = 150 um.

K-means clustering and Silhouette analysis were used to further examine groupings. Given the known heterogeneity of the DR, we anticipated that more then two groups of ROIs existed. Therefore we specified 3, 4, 5 or 6 groups for K-means and evaluated the resulting Silhouette plots. A positive Silhouette value indicates an ROI is more similar to individuals within the group then to individuals in other groups, and is therefore well assigned. Negative silhouette values indicate a poorly assigned group. Specifying 4 groups for K-means clustering was the only scenario that yielded consistently positive Silhouette values. The four groups are color-coded on the dendrogram produced by hierarchical clustering (Fig. 4). There was 93% concordance between hierarchical Ward’s method and agglomerative K-means clustering in that 2 of 30 ROIs shifted. The caudal-DR and MR groups were identical with K-means and Ward’s methods. In the rostral DR, two ROIs changed position to generate one group primarily involving the midline DR, while the other largely contained the lateral groups.

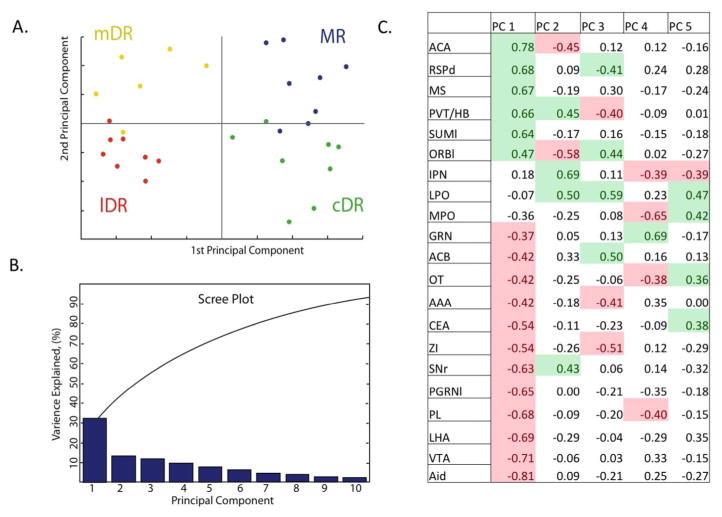

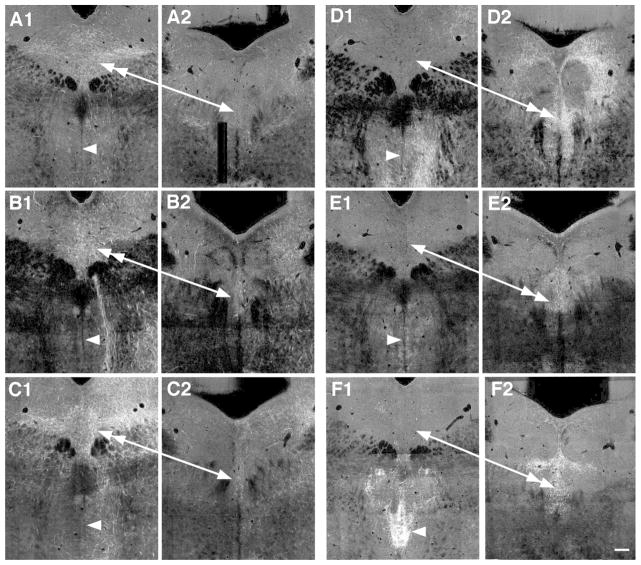

Principal component analysis showed that the first principal component divided the rostral DR from the caudal DR and MR (Fig. 5). The first principal component accounted for over 30% of the variance in the data, which was notably more then the remaining principal components, as seen on the Scree Plot (Fig. 4). This ‘elbow’ in the Scree plot reveals that the factors that drive the division of the ROIs into two groups are more robust then those that underlie subsequent divisions. Of the 21 injection sites, 18 had significant correlations (p<0.05) with the first principal component (Fig. 5), a 19th had borderline significance (p=0.052). Of the 18, 6 correlates were positive and the remaining 12 were negative. The opposing valance of these correlations raises the possibility that these 2 groups of projections had reciprocal innervation patterns. Studying images of the projection cases that had positive and negative correlations revealed the reciprocal preference of these projections to favor either the rostral DR or the caudal DR and MR (Fig. 6). That is, there was a group of projection cases that targeted the caudal DR heavily and were light in the rostral DR, while the other group was heavy in the rostral DR and light in the caudal DR. The caudal DR corresponded well to the areas that are designated DR-C and DR-I on the Paxinos Atlas (Paxinos and Franklin, 2004) located caudal to the decussation of the cerebellar peduncle. Afferents that heavily innervated the caudal DR also tended to similarly ramify within the MR.

Figure 5.

Principal component analysis. A. ROIs plotted with respect to first and second principle components, color-coded according to grouping in the midline-rostral DR (mDR, yellow), lateral rostral DR (lDR, red), MR (blue) or caudal DR (cDR, green). B. Scree plot shows that the first principle component accounts for >30% of the variance in the projections. Subsequent principle components are less robust, making smaller contributions to the overall variance in the data. C. Correlation coefficients (R values) between each projection and the first 5 principle components. Projections are ordered in relation to their correlation to the first principle component. Significant correlations (P< 0.05) are colorized green (positive correlations) or pink (negative correlations). When correlation coefficients have opposing valence with respect to a single principal component, it suggests these cases have reciprocal innervation patterns. Eighteen projections show significant correlation with the first principle component. Seven or fewer projection cases correlate with subsequent principal components.

Figure 6.

Images at rostral and caudal levels of the DR of projections that preferentially distributed to either the rostral DR or caudal DR and MR, i.e. had a negative or positive correlation to the first principal component. Negative correlates preferring the rostral DR are projections from the agranular insula (A1, A2), ventral tegmental area (B1, B2) and lateral hypothalalmic area (C1, C2). In these cases fibers are denser in the rostral DR (double-headed arrow) then the caudal DR (single arrow) or the MR (arrowheads). Positive correlates are projections from the anterior cingulate cortex (D1, D2), medial septum (E1, E2) and paraventricular nucleus of the thalamus/lateral habenula (F1, F2). In these cases innervation of the caudal DR (double-headed arrow), and typically the MR (arrowhead) is denser then in the rostral DR (single arrow). Image credit: Allen Institute for Brain Science. All panels same scale Bar = 150 um.

More subtle variation in innervation patterns drove the differences between the rostral midline from the lateral DR, and between the caudal DR from the MR and these did not appear to correspond to a single principle component.

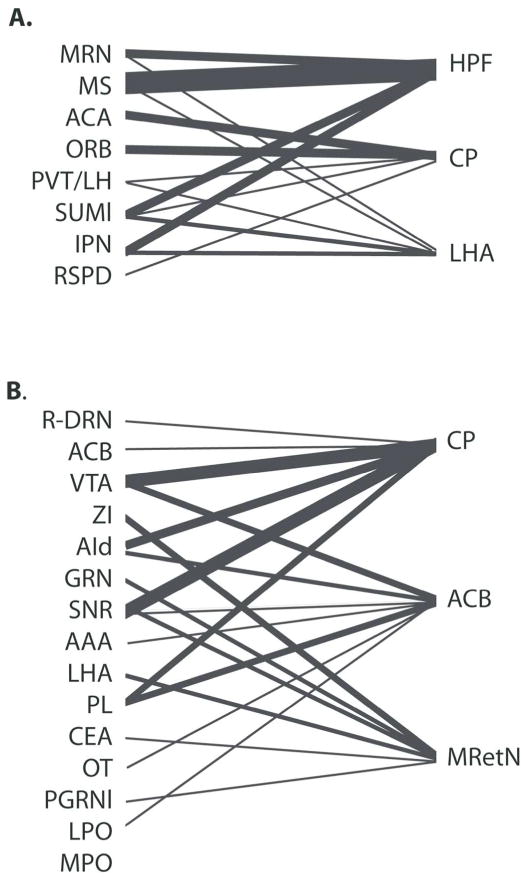

Next we re-analyzed the same data set, but from a different perspective. Specifically we transposed the data set and used clustering analysis to group projections with similar patterns of innervation. That is, instead of grouping ROIs by similarities in afferent innervation, we sought to group projection cases by their propensity to innervate similar ROIs. This analysis gives insight into how projections from different brain regions compare or relate to each other. The results showed there were two major groups of projection cases (Fig. 7). Members of one group tended to innervate the rostral DR more then the caudal DR or MR, while members of the other group exhibited the reciprocal pattern. That is, these groups corresponded to those that had positive or negative correlations to the first principal component in Fig. 5.

Figure 7.

Clustering of similar projection cases. A. The dendrogram generated with Ward’s method has two main branches. These correspond to projections that had negative/positive correlates with the first principal component in Fig. 3, i.e. prefer either the rostral DR or caudal DR and MR. K-means clustering (colorized) identifies four groups. Examination of the data matrix reveals that these correspond well to regions that had maximal distribution in an ROI located midline rostral (yellow), lateral rostral (red), in the caudal DR (green) or MR (blue). The single exception to that rule is the MPO, which has a maximal distribution lateral and thus matches better with it’s sorting by Ward’s method as indicated by it’s position on the dendrogram, rather then it’s color.

It was possible to further subdivide each of these two major groups of projection cases. By dictating 4 groups for K-means clustering, each of the two primary groups were divided again, with one area changing position (Fig. 7). By checking the database as well as the images of the projections, we determined that membership in each group was characterized by having heavy innervation in one of the four regions identified: midline rostral DR, lateral rostral DR, caudal DR or the MR (Fig. 7 and 8). The projection case that changed groups with K-means vs. hierarchical clustering was the MPO, and using the midline vs. lateral criteria, this projection case would fit better with projections favoring the lateral DR (color coded red) (Fig. 7 and 8). Differences between the midline rostral, lateral rostral and between caudal DR and MR consisted of more subtle gradients in afferent innervation then was apparent between the rostral and caudal DR.

We further analyzed the two major groups of projection cases to get more insight into the role of the two networks. That is, we asked what brain regions are commonly targeted by each group of regions, at the level of the first and most pronounced division between rostral DR and caudal DR/MR. This analysis was prompted by the observation that neural networks often exhibit small-world characteristics, coupled with knowledge that the hippocampus is a target of many of the brain areas that innervate the caudal DR and MR. On the Allen Mouse Brain Connectivity Atlas, quantitative information is available that describes how each injection case distributes axons to every other anatomically defined region of the brain. The target receiving the highest average percentage of innervation from areas innervating the caudal DR/MR determined from the data was the hippocampal formation (Fig. 9). The hippocampus was followed by the caudate putamen and lateral hypothalamic area. Common targets of rostral DR-related areas determined using this analysis (Fig. 9) were the caudate putamen and nucleus accumbens, followed by the midbrain reticular nucleus (which is the area designated deep mesencephalic nucleus (DpMe) by Paxinos and Franklin (Paxinos and Franklin, 2004)). Since innervation to these target areas may include both axons of passage and axons in terminal zones, the original 2D section images were examined to confirm the presence of ramifying axons with boutons in each of these areas (Oh et al., 2014). Ramifying axons were confirmed in all cases depicted. In addition to ramifying axons, axons of passage were identified in the caudate putamen for the cases where the injection sites originated in the ACA, ORB, AI and PL cortical areas.

Figure 9.

Major targets of MR and rostral DR networks, as determined using ‘projection summary details’ available on the Allen Mouse Brain Connectivity Atlas (Oh et al., 2014). A. The top three common targets of caudal DR and MR preferring cases, and the MR itself, are the hippocampal formation (HPF), caudate putamen (CP) and lateral hypothalamic area (LHA). B. Top three common targets of rostral-DR networks are the caudate putamen (CP), nucleus accumbens (ACB) and midbrain reticular nucleus (MRetN).

Discussion

This is the first study to use an informatics analysis to study organization of serotonin neurons within the DR. Analysis of projections from multiple brain areas to the DR revealed that there are very distinct networks associated with the rostral vs. caudal poles of this nucleus. In fact, the caudal DR was more similar to the MR then the remaining rostral DR. Therefore separate consideration of the rostral and caudal DR will simplify study of the DR by reducing this structure to more cohesive and functionally related zones. These results do not preclude the likelihood of additional functionally relevant subdivisions of the MR and DR. Indeed there were differences noted between midline and lateral components of the rostral DR as well as between the caudal DR and MR.

The DR is a large and heterogeneous group of neurons and has been divided into various subzones ever since the discovery of serotonin neurons (Dahlstrom and Fuxe, 1964; Steinbusch, 1984; Baker et al., 1990; Jacobs and Azmitia, 1992). Most recently nine disparate regions of the DR have been identified based on cytoarchitecture and to some extent differential connectivity (Hale and Lowry, 2011). This analysis perhaps suggests that each individual subregion is equally unique and unrelated to all other subregions. However, the association of these subregions to function is not unique with multiple regions linked with anxiety or sleep, or broadly classified as relevant to ‘affective disorder’, ‘behavioral state’ or in some cases, ‘unknown’ (Hale and Lowry, 2011). Therefore key functional subregions of DR remain to be identified. At the same time others in the field have argued that serotonin neurons with the DR comprise a single cell type and differences in cytoarchitecture and other features are not yet compelling enough to justify any division of the nucleus (Andrade and Haj-Dahmane, 2013).

The informatics approach used here advances the understanding of organization of the DR and MR because it suggests divisions that are based on data analysis. The data has limitations associated with the precise alignment of sections and resolution at the level of axons rather then synaptic contacts. Nevertheless afferent innervation is critical for function because it plays a direct role in controlling neuronal activation state (Sporns, 2011). Therefore by nature the data has relevance from the level of synaptic properties to that of behavioral function. Moreover, informatics analysis reveals the relative magnitude of differences between subgroups of areas. Thus new information revealed by the analysis was that the division between the rostral two thirds and caudal third is the single most substantive division of the DR, suggesting major functional differences fall along this line as well. Likewise, subregions within each of these areas appear to have greater degree of similarity with each other, suggesting their roles are somehow more related.

The informatics analysis is also unique because it is unbiased by the conventional distinction between the DR and the MR, and reveals that the caudal DR is more related to the MR then to the rostral DR. However, this finding has precedents in the literature and echoes the organization of forebrain afferent projections arising from the DR and MR. That is, the rostral DR is known to have unique forebrain targets compared to the caudal DR, while projections of the caudal DR resemble those of the MR. For example, the rostral DR exclusively innervates the dorsal striatum (Imai et al., 1986). In contrast, the caudal DR and MR share innervation of both the septum and hippocampus both in the rat (Imai et al., 1986; Vertes and Linley, 2008) and mouse (Muzerelle et al., 2014). Taken together, these observations suggest that the caudal DR may be more accurately viewed as a dorsal extension of the MR, rather then as a caudal component of the DR.

The similarity of the caudal DR to the MR and distinction from the rostral DR may be related to the development of the hindbrain. The entire DR, as well as part of the MR arises from rhombomere 1 (R1) defined by the expression of engrailed-1 (Jensen et al., 2008), which includes both the isthmic portion of R1, also called the isthmus, as well as the caudal part of R1 or R1 proper. A recent study examining serotonin neurons from a developmental perspective emphasized that the rostral part of DR originates from the isthmus, whereas caudal to the decussation of the cerebellar peduncle, the DR and a portion of the MR have a common developmental origin from within R1 proper (Alonso et al., 2013), a finding hinted at previously (Jacobs and Azmitia, 1992). Indeed when visualized in sagittal sections the caudal DR and the MR are contiguous, with the MR extending at an angle ventral and rostral to the caudal DR (Molliver, 1987). Standard coronal sections are skewed with respect to the relevant developmental zones, making the caudal DR appear less related to the MR (Alonso et al., 2013). These observations suggest that developmental history may relate to the common features of network connectivity of the caudal DR and the MR, and distinguish them both from the rostral DR.

Recent retrograde tract-tracing studies in the mouse have comprehensively described the afferents to serotonin neurons in the MR and/or DR (Ogawa et al., 2014; Pollak Dorocic et al., 2014; Weissbourd et al., 2014). The overall results of this study are consistent with the reported preferential affiliation of the DR, vs. the MR, with mesolimbic and nigrostriatal dopamine systems (Ogawa et al., 2014; Pollak Dorocic et al., 2014). Further, the retrograde approaches also converge to indicate the DR likely receives substantial sensory- or somatic-state information via connections with the amgydala and medullary areas, areas that were noted to have a common regional distribution in the DR (Weissbourd et al., 2014) and to favor the DR over MR (Ogawa et al., 2014; Pollak Dorocic et al., 2014). The current results suggest all of these connections would be primarily attributable to the rostral two-thirds of the DR. Many of the basal forebrain areas that innervate the rostral part of the DR are reciprocally innervated by serotonin neurons in the same location (Muzerelle et al., 2014). In addition, the rostral part of the DR is the major source of serotonin in the cortex (Muzerelle et al., 2014). Taken together, connectivity of the rostral DR suggests a network that integrates sensory information and engages appropriate goal or reward directed behavior such as feeding or reproductive behavior, with the capacity to coordinate cortical function.

The connections of the caudal DR stand in contrast to those of the rostral DR. While the rostral DR is associated with mesolimbic systems that encode positive reward the caudal DR, like the MR, is closely linked to the lateral habenula, which encodes negative reward raising the possibility that these two major groups of serotonin neurons may be differentially relevant to situations of opposing hedonic valence (Matsumoto and Hikosaka, 2009). Previous studies have associated both the caudal DR and MR with response to stressful or adverse circumstances (Grahn et al., 1999; Hammack et al., 2002; Konno et al., 2007; Sperling and Commons, 2011). The hippocampus figures prominently as a common target of the caudal DR and MR (Muzerelle et al., 2014), as well as their network partners. While the association of the MR, septum and supramammillarly nucleus to hippocampal theta is well established (Maru et al., 1979; Kocsis and Vertes, 1996; Vertes and Kocsis, 1997; Kirk and Mackay, 2003; Pan and McNaughton, 2004; Crooks et al., 2012), the interpeduncular nucleus, habenula and the pathway between them are also implicated in regulating hippocampal theta (Valjakka et al., 1998; Funato et al., 2010; Aizawa et al., 2013; Goutagny et al., 2013). Taken together, these findings suggest both the caudal DR and MR contribute to networks that influence arousal and learning state, particularly under aversive conditions.

Caudal and rostral DR differ in both their afferent and efferent projections, suggesting they each fill a distinct functional niche. The similarity of the caudal DR with the MR, and distinction from the rostral DR is likely related to their developmental origins (Alonso et al., 2013). Thus as currently defined, the DR includes two very distinct areas and this would contribute to a heterogeneous view of the DR, and lack of differentiation from the MR. Indeed, the inclusion of two distinct networks within the DR could represent a complication, if not a confound in the literature up to this point. This study suggests improved ways to conceptualize the organization of ascending serotonin from the MR and DR, that is, by either separately considering the caudal DR or affiliating it with the MR. Using increasingly refined approaches, future studies will improve upon this scheme by identifying how afferents, efferents and the existence of different neuronal cell-types work together to define meaningful subregions of the rostral DR, caudal DR and MR. A better understanding of the organization of these areas and how they relate to each other will help understand their role in normal behavior and how their malfunction could drive particular psychological disorders.

Acknowledgments

I am indebted to the assistance of Dr. Yue Ping Guo for help with image selection, organization and registration and to Dr. Ben Okaty for advice with statistics, Matlab and critical reading of the manuscript. The Sara Page Mayo Foundation for Pediatric Pain Research and National Institutes of Health grant DA021801 financially supported this study.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Statement: Dr. Commons has no known or potential conflict of interest.

Role of Authors: Dr. Commons had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. She was responsible for all components of the study and manuscript preparation.

Literature cited

- Aizawa H, Yanagihara S, Kobayashi M, Niisato K, Takekawa T, Harukuni R, McHugh TJ, Fukai T, Isomura Y, Okamoto H. The synchronous activity of lateral habenular neurons is essential for regulating hippocampal theta oscillation. J Neurosci. 2013;33(20):8909–8921. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4369-12.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alonso A, Merchan P, Sandoval JE, Sanchez-Arrones L, Garcia-Cazorla A, Artuch R, Ferran JL, Martinez-de-la-Torre M, Puelles L. Development of the serotonergic cells in murine raphe nuclei and their relations with rhombomeric domains. Brain Struct Funct. 2013;218(5):1229–1277. doi: 10.1007/s00429-012-0456-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrade R, Haj-Dahmane S. Serotonin neuron diversity in the dorsal raphe. ACS chemical neuroscience. 2013;4(1):22–25. doi: 10.1021/cn300224n. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker KG, Halliday GM, Tork I. Cytoarchitecture of the human dorsal raphe nucleus. J Comp Neurol. 1990;301(2):147–161. doi: 10.1002/cne.903010202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crooks R, Jackson J, Bland BH. Dissociable pathways facilitate theta and non-theta states in the median raphe--septohippocampal circuit. Hippocampus. 2012;22(7):1567–1576. doi: 10.1002/hipo.20999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahlstrom A, Fuxe K. Localization of monoamines in the lower brain stem. Experientia. 1964;20(7):398–399. doi: 10.1007/BF02147990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Funato H, Sato M, Sinton CM, Gautron L, Williams SC, Skach A, Elmquist JK, Skoultchi AI, Yanagisawa M. Loss of Goosecoid-like and DiGeorge syndrome critical region 14 in interpeduncular nucleus results in altered regulation of rapid eye movement sleep. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107(42):18155–18160. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1012764107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goutagny R, Loureiro M, Jackson J, Chaumont J, Williams S, Isope P, Kelche C, Cassel JC, Lecourtier L. Interactions between the lateral habenula and the hippocampus: implication for spatial memory processes. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2013;38(12):2418–2426. doi: 10.1038/npp.2013.142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grahn RE, Will MJ, Hammack SE, Maswood S, McQueen MB, Watkins LR, Maier SF. Activation of serotonin-immunoreactive cells in the dorsal raphe nucleus in rats exposed to an uncontrollable stressor. Brain Res. 1999;826(1):35–43. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(99)01208-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hale MW, Lowry CA. Functional topography of midbrain and pontine serotonergic systems: implications for synaptic regulation of serotonergic circuits. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2011;213(2–3):243–264. doi: 10.1007/s00213-010-2089-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammack SE, Richey KJ, Schmid MJ, LoPresti ML, Watkins LR, Maier SF. The role of corticotropin-releasing hormone in the dorsal raphe nucleus in mediating the behavioral consequences of uncontrollable stress. J Neurosci. 2002;22(3):1020–1026. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-03-01020.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imai H, Steindler DA, Kitai ST. The organization of divergent axonal projections from the midbrain raphe nuclei in the rat. J Comp Neurol. 1986;243(3):363–380. doi: 10.1002/cne.902430307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs BL, Azmitia EC. Structure and function of the brain serotonin system. Physiol Rev. 1992;72(1):165–229. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1992.72.1.165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen P, Farago AF, Awatramani RB, Scott MM, Deneris ES, Dymecki SM. Redefining the serotonergic system by genetic lineage. Nat Neurosci. 2008;11(4):417–419. doi: 10.1038/nn2050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirk IJ, Mackay JC. The role of theta-range oscillations in synchronising and integrating activity in distributed mnemonic networks. Cortex; a journal devoted to the study of the nervous system and behavior. 2003;39(4–5):993–1008. doi: 10.1016/s0010-9452(08)70874-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kocsis B, Vertes RP. Midbrain raphe cell firing and hippocampal theta rhythm in urethane-anaesthetized rats. Neuroreport. 1996;7(18):2867–2872. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199611250-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konno K, Matsumoto M, Togashi H, Yamaguchi T, Izumi T, Watanabe M, Iwanaga T, Yoshioka M. Early postnatal stress affects the serotonergic function in the median raphe nuclei of adult rats. Brain Res. 2007;1172:60–66. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2007.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lein ES, Hawrylycz MJ, Ao N, Ayres M, Bensinger A, Bernard A, Boe AF, Boguski MS, Brockway KS, Byrnes EJ, Chen L, Chen TM, Chin MC, Chong J, Crook BE, Czaplinska A, Dang CN, Datta S, Dee NR, Desaki AL, Desta T, Diep E, Dolbeare TA, Donelan MJ, Dong HW, Dougherty JG, Duncan BJ, Ebbert AJ, Eichele G, Estin LK, Faber C, Facer BA, Fields R, Fischer SR, Fliss TP, Frensley C, Gates SN, Glattfelder KJ, Halverson KR, Hart MR, Hohmann JG, Howell MP, Jeung DP, Johnson RA, Karr PT, Kawal R, Kidney JM, Knapik RH, Kuan CL, Lake JH, Laramee AR, Larsen KD, Lau C, Lemon TA, Liang AJ, Liu Y, Luong LT, Michaels J, Morgan JJ, Morgan RJ, Mortrud MT, Mosqueda NF, Ng LL, Ng R, Orta GJ, Overly CC, Pak TH, Parry SE, Pathak SD, Pearson OC, Puchalski RB, Riley ZL, Rockett HR, Rowland SA, Royall JJ, Ruiz MJ, Sarno NR, Schaffnit K, Shapovalova NV, Sivisay T, Slaughterbeck CR, Smith SC, Smith KA, Smith BI, Sodt AJ, Stewart NN, Stumpf KR, Sunkin SM, Sutram M, Tam A, Teemer CD, Thaller C, Thompson CL, Varnam LR, Visel A, Whitlock RM, Wohnoutka PE, Wolkey CK, Wong VY, Wood M, Yaylaoglu MB, Young RC, Youngstrom BL, Yuan XF, Zhang B, Zwingman TA, Jones AR. Genome-wide atlas of gene expression in the adult mouse brain. Nature. 2007;445(7124):168–176. doi: 10.1038/nature05453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maru E, Takahashi LK, Iwahara S. Effects of median raphe nucleus lesions on hippocampal EEG in the freely moving rat. Brain Res. 1979;163(2):223–234. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(79)90351-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsumoto M, Hikosaka O. Representation of negative motivational value in the primate lateral habenula. Nat Neurosci. 2009;12(1):77–84. doi: 10.1038/nn.2233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molliver ME. Serotonergic neuronal systems: what their anatomic organization tells us about function. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 1987;7(6 Suppl):3S–23S. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muzerelle A, Scotto-Lomassese S, Bernard JF, Soiza-Reilly M, Gaspar P. Conditional anterograde tracing reveals distinct targeting of individual serotonin cell groups (B5–B9) to the forebrain and brainstem. Brain Struct Funct. 2014 doi: 10.1007/s00429-014-0924-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogawa SK, Cohen JY, Hwang D, Uchida N, Watabe-Uchida M. Organization of monosynaptic inputs to the serotonin and dopamine neuromodulatory systems. Cell reports. 2014;8(4):1105–1118. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2014.06.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oh SW, Harris JA, Ng L, Winslow B, Cain N, Mihalas S, Wang Q, Lau C, Kuan L, Henry AM, Mortrud MT, Ouellette B, Nguyen TN, Sorensen SA, Slaughterbeck CR, Wakeman W, Li Y, Feng D, Ho A, Nicholas E, Hirokawa KE, Bohn P, Joines KM, Peng H, Hawrylycz MJ, Phillips JW, Hohmann JG, Wohnoutka P, Gerfen CR, Koch C, Bernard A, Dang C, Jones AR, Zeng H. A mesoscale connectome of the mouse brain. Nature. 2014;508(7495):207–214. doi: 10.1038/nature13186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan WX, McNaughton N. The supramammillary area: its organization, functions and relationship to the hippocampus. Prog Neurobiol. 2004;74(3):127–166. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2004.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paxinos G, Franklin K. The Mouse Brain in Stereotaxic Coordinates. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Peyron C, Petit JM, Rampon C, Jouvet M, Luppi PH. Forebrain afferents to the rat dorsal raphe nucleus demonstrated by retrograde and anterograde tracing methods. Neuroscience. 1998;82(2):443–468. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(97)00268-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollak Dorocic I, Furth D, Xuan Y, Johansson Y, Pozzi L, Silberberg G, Carlen M, Meletis K. A whole-brain atlas of inputs to serotonergic neurons of the dorsal and median raphe nuclei. Neuron. 2014;83(3):663–678. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2014.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sperling R, Commons KG. Shifting topographic activation and 5-HT1A receptor-mediated inhibition of dorsal raphe serotonin neurons produced by nicotine exposure and withdrawal. Eur J Neurosci. 2011;33(10):1866–1875. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2011.07677.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sporns O. Networks of the Brain. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Steinbusch HWM. Serotonin-immnoreactive neurons and their projections in the CNS. In: AB, TH, MJK, editors. Handbook of Chemical Neuroanatomy. Vol. 3. Elsevier Science Publishers; 1984. pp. 68–121. [Google Scholar]

- Valjakka A, Vartiainen J, Tuomisto L, Tuomisto JT, Olkkonen H, Airaksinen MM. The fasciculus retroflexus controls the integrity of REM sleep by supporting the generation of hippocampal theta rhythm and rapid eye movements in rats. Brain Res Bull. 1998;47(2):171–184. doi: 10.1016/s0361-9230(98)00006-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vasudeva RK, Lin RC, Simpson KL, Waterhouse BD. Functional organization of the dorsal raphe efferent system with special consideration of nitrergic cell groups. J Chem Neuroanat. 2011 doi: 10.1016/j.jchemneu.2011.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vertes R, Linley S. Efferent and afferent connections of the dorsal and median raphe nuclei in the rat. In: Monti J, Pandi-Perumal S, Jacobs B, Nutt D, editors. Serotonin and Sleep: Molecular, Functional and Clinical Aspects. Switzerland: Birkhauser Verlag; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Vertes RP, Kocsis B. Brainstem-diencephalo-septohippocampal systems controlling the theta rhythm of the hippocampus. Neuroscience. 1997;81(4):893–926. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(97)00239-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Q, Henry AM, Harris JA, Oh SW, Joines KM, Nyhus J, Hirokawa KE, Dee N, Mortrud M, Parry S, Ouellette B, Caldejon S, Bernard A, Jones AR, Zeng H, Hohmann JG. Systematic comparison of adeno-associated virus and biotinylated dextran amine reveals equivalent sensitivity between tracers and novel projection targets in the mouse brain. J Comp Neurol. 2014;522(9):1989–2012. doi: 10.1002/cne.23567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waselus M, Valentino RJ, Van Bockstaele EJ. Collateralized dorsal raphe nucleus projections: A mechanism for the integration of diverse functions during stress. J Chem Neuroanat. 2011 doi: 10.1016/j.jchemneu.2011.05.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weissbourd B, Ren J, DeLoach KE, Guenthner CJ, Miyamichi K, Luo L. Presynaptic partners of dorsal raphe serotonergic and GABAergic neurons. Neuron. 2014;83(3):645–662. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2014.06.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]