Abstract

Background:

The relationship between diabetes and periodontitis has been studied for more than 50 years and is generally agreed that the periodontal disease is more prevalent in diabetic patients compared to nondiabetics. Vascular changes like increased thickness of basement membrane in small vessels has been reported in diabetic patients, but the quantity of blood vessels in gingiva of diabetic patients has not been discussed much. The aim of this study was to compare the number of blood vessels in gingiva between chronic periodontitis (CP) patients, CP with diabetes (type 2), and normal healthy gingiva.

Materials and Methods:

The study included 75 patients, divided into three groups of 25 patients each-Group I with healthy periodontium (HP), Group II with CP, and Group III with CP with diabetes mellitus (CPDM). Gingival biopsies were obtained from the subjects undergoing crown lengthening procedure for Group I, and in patients with CP and in CPDM biopsies were collected from teeth undergoing extraction. Sections were prepared for immune histochemical staining with CD34.

Results:

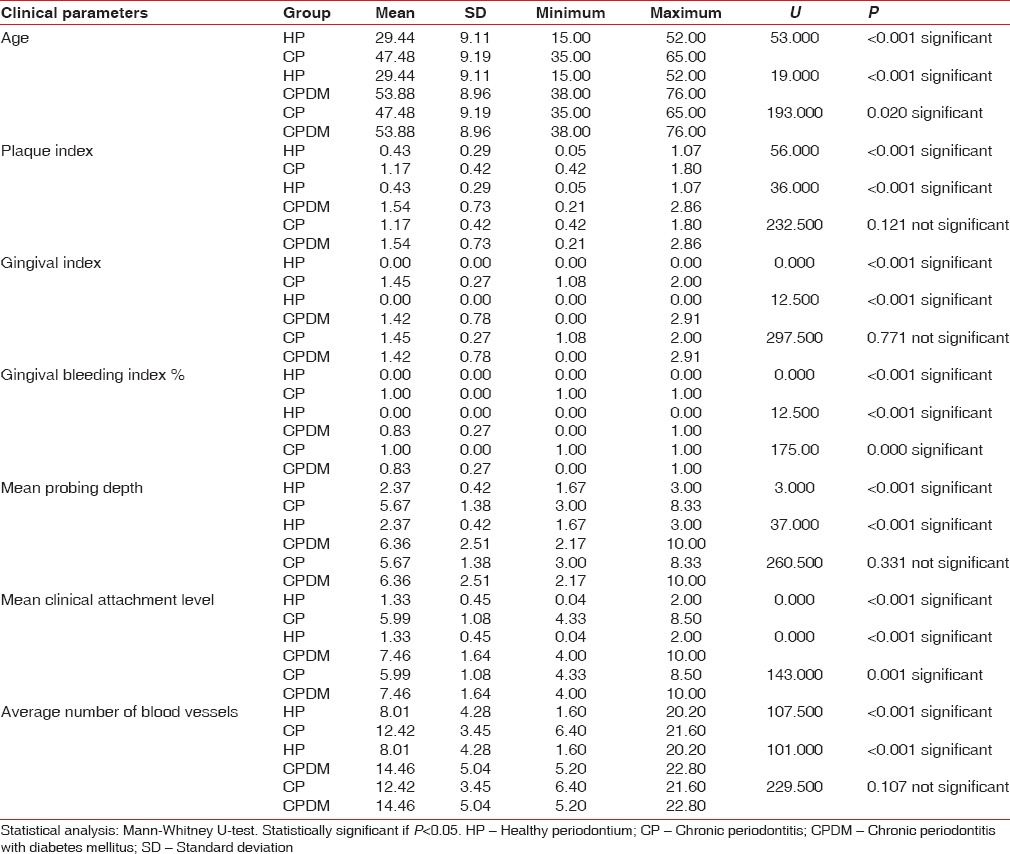

Difference was observed in the average number of blood vessels when compared between HP, CP, and CPDM groups. Statistical significant difference was observed when the HP and CP groups and HP and CPDM groups were compared.

Conclusion:

The results of the study indicated that the number of blood vessels in gingival connective tissue is significantly higher in CP and CPDM patients.

Keywords: CD34, chronic periodontitis with diabetes, mean vessel number, periodontitis, type 2 diabetes

INTRODUCTION

Diabetes mellitus has emerged as a major health issue worldwide representing a spectrum of metabolic disorders characterized by abnormalities in carbohydrate, protein, and lipid metabolism. With no country spared from the burden of diabetes, this complex metabolic disorder is the third leading cause of death in the United States.[1] India has earned the dubious distinction of being called the diabetes capital of the world. The association between periodontitis and diabetes has also been extensively studied, and the bi-directional relationship between the two has been established far beyond doubt.

Gingiva being a highly vascular tissue with intact vascular system is essential for the continued delivery of oxygen and nutrients to the tissues along with the removal of waste products both of which are required to maintain proper tissue function. Impairment of carbohydrate, protein, and lipid metabolism in diabetes has often been associated with periodontal vascular changes like increased thickness of basement membrane in small blood vessels with the damage occurring in the endothelial cells constituting the lining of small and large vessels leading to micro and macro-vascular complications.[2] These changes have been hypothesized leading to impediment in oxygen diffusion, metabolic waste elimination, leukocyte migration, and diffusion of immune factors. The poor metabolic control and longer duration of the disease have been attributed to the worsening of vascular changes.

These vascular changes in the diabetic state referred to as arteriosclerotic aging also indicate that the gingival vascular bed accurately reflects the general state of these patients with a significant number of vascular abnormalities being elicited in the gingival tissue from diabetics.[3,4]

One of the pathologic factors attributed to an increase in the number of blood vessels in the gingival connective tissues is the elevated levels of cytokines in the diabetic patients.[5] Guiseppe showed that the density of the vessels of superficial periodontium (masticatory or gingival mucosa) in diabetic patients is nearly double that of healthy subjects.[6]

Research was done related to gingival vascular changes in diabetic patients with periodontitis but not much data is available from histological studies using a specific marker for endothelial cells and the number of blood vessels. Hence, an attempt was made by us to compare the number of blood vessels in the gingival connective tissue of healthy patients with chronic periodontitis (CP) with and without diabetes mellitus using CD34 immuno-histochemical marker.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study design

Study population comprised of patients attending the Department of Periodontics, Vishnu Dental College and Hospital. A total of 75 subjects were included in the study and were divided into three groups of 25 subjects each which included healthy, CP, and CP with diabetes mellitus (CPDM) type 2. A total of 75 individuals was divided as following;[7]

Group I – 25 patients of healthy periodontium (HP) with no features of gingival inflammation, undetectable bleeding on probing and probing depth of <3 mm with no demonstrable loss of attachment

Group II – 25 patients of CP with a probing depth ≥4 mm and CAL ≥ 3 mm which was confirmed by demonstrable intra oral periapical radiographs in at least 6 teeth

Group III – 25 patients of CPDM for at least 3 years and were on medication (controlled glycemic level).

Patients who had not been treated for periodontitis over the previous 2 years and had not taken antibiotics in the past 6 months and with a minimum of 20 natural teeth were included. Those teeth with no periodontal disease and which required crown lengthening for restorative procedures for the first time and not already existing restorations with biologic width violation were included in the study.[8,9] Patients with smoking, alcohol habits, with other systemic complications other than diabetes mellitus and with hemoglobinopathies were excluded in this study. Informed consent was obtained, and ethical clearance was taken from the Institutional Review Board, Vishnu Dental College, Bhimavaram.

Clinical evaluation of subjects

After obtaining a thorough medical and dental history evaluation of subjects was performed by using a sterile mouth mirror and a Williams graduated periodontal probe using plaque index,[10] gingival index,[11] gingival bleeding index,[12] mean probing pocket depth, and clinical attachment level.

Procedure for obtaining gingival tissues

In patients with HP gingival biopsies were collected from the subjects undergoing crown lengthening procedure, whereas in patients with CP and in CPDM biopsies were collected from teeth undergoing extraction with Grade III mobility and in cases where in the prognosis was considered hopeless.

Tissue preparation

The samples were fixed in 10% neutral buffered formaldehyde for 24–48 h, embedded in paraffin, sectioned at 5-μm thickness and stained with hematoxylin and eosin to observe the tissue representation that included the subepithelial, superficial, and deep connective tissue of the gingiva. To evaluate the mean vessel number, sections were stained immune-histochemically.

Staining procedure

Sections, 5-μm thick, were mounted on positive charged microscope slides. After de-waxing in xylene, sections were dehydrated in ethanol, rinsed in distilled water. Slides were placed in tri-sodium citrate buffer solution (pH = 6) for antigen retrieval, in a microwave for 15 min at 600 W. Slides were exposed to peroxide and protein block for 10 min each and CD34 mouse anti-human antibody (Biogenex, clone Q Bend/10, Biogenex Laboratories Inc., San Ramon, CA, USA) for 60 min at room temperature. Slides were rinsed in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) for 5 min. Super enhancer was added and for antibody detection, universal immune peroxidase polymer antimouse antibody was used. Sections were rinsed in PBS for 10 min, and reacted with diaminobenzidine (DAB) chromogen for 10 min and counterstained with Harris's hematoxylin and mounted with DPX. Sections treated with the above protocol with no primary antibody added served as a negative control.

Immuno-histochemical evaluation of CD34 positive blood vessels

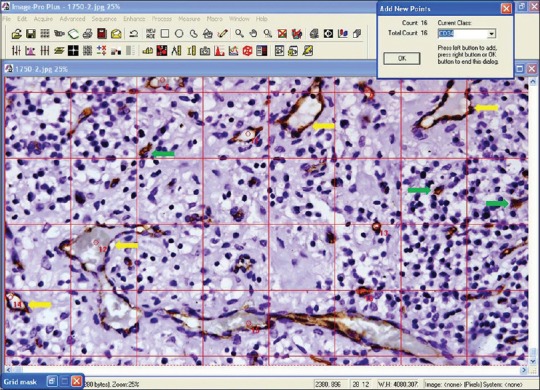

Brown staining was considered as positive staining. Pyogenic granuloma was taken as a positive control. For each section, the endothelial cells that had a positive reaction with CD34 and with an established lumen were counted at five high power fields [Figure 1]. Counts were performed on Olympus microscope using image pro plus image analysis software. Results were presented as the mean number of CD34 positive blood vessels for that sample.

Figure 1.

CD34 stained blood vessels in chronic periodontitis with diabetes mellitus patient (yellow arrows represent blood vessels and not all blood vessels are marked). Green arrows represent individual cells stained brown with CD34, possibly representing endothelial progenitor cells or hematopoietic stem cells. These cells were not counted (×40)

Statistical analysis

The comparison of changes among groups (HP, CP, CPDM) was tested by Kruskal–Wallis variance analysis and Mann–Whitney U-test was used for pairwise comparison of the groups. P < 0.05 was considered as statistically significant for all the analysis.

RESULTS

There was a statistically significant difference between HP, CP, and CPDM regarding all clinical parameters and vessel number (P ≤ 0.05). Table 1 shows the comparison of clinical parameters and vessel numbers between HP and CP, HP and CPDM, CP and CPDM. In intra-group comparison, all the above-mentioned parameters showed statistically significant difference between the groups. No statistical significant difference was observed when the CP and CPDM groups were compared for the average number of blood vessels.

Table 1.

Comparison of clinical parameters and vessel numbers between the HP and CP

DISCUSSION

The present study was conducted immuno-histochemically using CD34 antibody and revealed that there was significant difference in the number of blood vessels between HP, CP, and CPDM groups and interestingly, no significant difference was established between CP and CPDM.

CD34, a cluster differentiation molecule is a trans membrane glycol protein that is expressed on human hematopoietic progenitor cells and a small vessel endothelium of a variety of tissues.[13] This is a more specific method of evaluating vascularization by immune-histochemically targeting the endothelial cells of blood vessels but not lymphatics.[14] Multiple factors have been advocated to explain the relationship between diabetes mellitus and periodontal disease that has been recognized as the six most important complication of diabetes mellitus. An altered immune inflammatory responsiveness to bacterial pathogens impairing the neutrophil functions and hyperresponsiveness of macrophage/monocyte during episodes of hyperglycemia has been reported.[15,16] Diabetic patients showed a diminution of formative aspects of connective tissue and increased apoptosis of matrix producing cells such as fibroblasts and osteoblasts in the presence of Porphyromonas gingivalis infection.[17,18,19]

Microvascular changes associated with diabetic complications such as abnormal growth and regeneration of blood vessels and accumulation of advanced glycation end products (AGEs) have been shown in periodontal tissues of the diabetic patients. The AGEs accumulate in the basement membranes of endothelial cells leading to increased membrane thickness and alteration in the normal hemostatic transport across the membrane.[16,20] In addition, these AGEs are also associated with increased production of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) which in turn is related to microangiopathy and increased angiogenesis[21] moreover reported to be elevated in gingival tissues of diabetic patients.[22] In response to the angiogenic stimuli, the vascular endothelial cells secrete proteinases[23] and was also suggested by Gross et al. that tissue degradation seen in the destructive periodontal lesion is the direct result of angiogenic events acting on vessels in inflamed gingiva causing changes in the anatomy of microcirculation and degradation of surrounding connective tissue elements.[24]

We have performed this study to understand whether CP patients with and without diabetes have a different mean vessel density compared to nondiabetic controls.

In our study, we observed that there is a significant increase in the average number of blood vessels in CP group compared to group with HP.

It is in agreement with earlier reports suggesting that the number of blood vessels in gingival connective tissues of periodontal pockets is higher than that of healthy periodontal tissues. Zoellner and Hunter[24] reported an increased number of vessels in the deep connective tissues of periodontal pockets with the development of the advanced periodontal lesion. They also suggested that this increase may be due to an increase in the number and loop formation of blood vessels. Bonakdar et al.[25] reported an increase in vascularity in sub epithelial connective tissue from chronic adult periodontitis lesions using dichromatic staining and transmission electron microscopy, suggesting that possible factors in this vascular change might be due to formation of new blood vessels. The relationship between an increased number of blood vessels and progression of the disease with marked thickening of basement membranes especially capillaries and venules were reported.[26] This increased endothelial surface can cause an increased transition of diverse cytokines, adhesion molecules, and other factors of inflammation. Johnson et al.[27] assessed VEGF in gingiva and compared them with interleukin-6 and number of blood vessels during the initiation and progression of inflammation and suggested that VEGF, by initiating an increase in the vascular network, might be responsible for initiation and progression of gingivitis to periodontitis, coincident to progression of the inflammation. Similarly, a statistically significant increase in the average number of blood vessels in CPDM group when compared with HP group was observed. A study by Scardina et al.[6] using videocapillaroscopy observed that the vascular bed in diabetic subjects showed an increase in the number of capillary loops per mm2 suggesting a strong angiogenic activity. The density of the vessels in diabetic subjects is nearly double that of healthy subjects. They described a characteristic periodontal capillary pattern in diabetic subjects appearing as “leopard spot” morphology, with diffused microhemorrhages and capillaries with a cockade pattern. Using experimental rat model for diabetes Sakallioglu et al.[28] evaluated the osmotic pressure and vascular diameter in gingival tissues and proposed a correlation between these two parameters. The authors also suggested the need to investigate the vascular changes in diabetic humans as their study involved only experimentally induced rat model.

In our study, CP and CPDM groups have shown similar clinical indices except for a percentage of gingival bleeding index and mean clinical attachment levels. We did not use any parameters associated with the various mechanisms. For this reason, we cannot suggest possible clinical factors affecting the vasculature of gingival connective tissues in CPDM.

No statistical significant difference was observed when CP and CPDM groups were compared for the average number of blood vessels (P = 0.107). This could be due to controlled glycemic status of the patients as this study was performed on diabetic subjects who were on medication and glycemic status was controlled which could have had an effect on the blood vessel proliferation or angiogenesis.

Many factors such as age of the patient, hypoxia state, and inflammation could affect the vascular proliferation thereby the number of vessels. In this study, these parameters were not appraised, and hence some limitations do exist.

CONCLUSION

The present study showed that diabetic patients with periodontitis showed increased number of vessels in gingival connective tissues than nondiabetic patients with periodontitis but was not statistically significant. Further studies are necessary on vascular changes in diabetic patients and antiangiogenic agents in prevention and treatment of periodontal diseases seen in diabetes.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Vishnu Dental College, Bhimavaram, Andhra Pradesh, India.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Little JW, Fallace DA, Miller CS, Rhodus NL. In: Dental Management of the Medically Compromised Patient. 5th ed. St. Louis: Mosby; 1997. Diabates; pp. 387–409. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Karakus A, Sengun D, Berberoglu A, Caglayan G, Usubutun A, Etikan L, et al. The immunohistological comparison of the number of gingival blood vessels between type 2 diabetes mellitus and chronic periodontitis patients. Hacettepe Dishekimligi Fakultesi Dergisi Cilt. 2007;31:52–60. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stahl SS, Witkin GJ, Scopp IW. Degenerative vascular changes observed in selected gingival specimens. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1962;15:1495–504. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(62)90415-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Russell BG. Gingival changes in diabetes mellitus. 1. Vascular changes. Acta Pathol Microbiol Scand. 1966;68:161–8. doi: 10.1111/apm.1966.68.2.161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Loos BG, Craandijk J, Hoek FJ, Wertheim-van Dillen PM, van der Velden U. Elevation of systemic markers related to cardiovascular diseases in the peripheral blood of periodontitis patients. J Periodontol. 2000;71:1528–34. doi: 10.1902/jop.2000.71.10.1528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Scardina GA, Cacioppo A, Messina P. Periodontal microcirculation in diabetics: An in vivo non-invasive analysis by means of videocapillaroscopy. Med Sci Monit. 2012;18:CR58–64. doi: 10.12659/MSM.882456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Eke PI, Page RC, Wei L, Thornton-Evans G, Genco RJ. Update of the case definitions for population-based surveillance of periodontitis. J Periodontol. 2012;83:1449–54. doi: 10.1902/jop.2012.110664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shobha KS, Mahantesha, Seshan H, Mani R, Kranti K. Clinical evaluation of the biological width following surgical crown-lengthening procedure: A prospective study. J Indian Soc Periodontol. 2010;14:160–7. doi: 10.4103/0972-124X.75910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Arora R, Narula SC, Sharma RK, Tewari S. Evaluation of supracrestal gingival tissue after surgical crown lengthening: A 6-month clinical study. J Periodontol. 2013;84:934–40. doi: 10.1902/jop.2012.120162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Loe H, Silness J. Periodontal disease in pregnancy. I. prevalence and severity. Acta Odontol Scand. 1963;21:533–51. doi: 10.3109/00016356309011240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Silness J, Loe H. Periodontal disease in pregnancy. II. Correlation between oral hygiene and periodontal condtion. Acta Odontol Scand. 1964;22:121–35. doi: 10.3109/00016356408993968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mühlemann HR, Son S. Gingival sulcus bleeding - A leading symptom in initial gingivitis. Helv Odontol Acta. 1971;15:107–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Simmons DL, Satterthwaite AB, Tenen DG, Seed B. Molecular cloning of a cDNA encoding CD34, a sialomucin of human hematopoietic stem cells. J Immunol. 1992;148:267–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Aspriello SD, Zizzi A, Lucarini G, Rubini C, Faloia E, Boscaro M, et al. Vascular endothelial growth factor and microvessel density in periodontitis patients with and without diabetes. J Periodontol. 2009;80:1783–9. doi: 10.1902/jop.2009.090239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Manouchehr-Pour M, Spagnuolo PJ, Rodman HM, Bissada NF. Comparison of neutrophil chemotactic response in diabetic patients with mild and severe periodontal disease. J Periodontol. 1981;52:410–5. doi: 10.1902/jop.1981.52.8.410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hanes PJ, Krishna R. Characteristics of inflammation common to both diabetes and periodontitis: Are predictive diagnosis and targeted preventive measures possible? EPMA J. 2010;1:101–16. doi: 10.1007/s13167-010-0016-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.He H, Liu R, Desta T, Leone C, Gerstenfeld LC, Graves DT. Diabetes causes decreased osteoclastogenesis, reduced bone formation, and enhanced apoptosis of osteoblastic cells in bacteria stimulated bone loss. Endocrinology. 2004;145:447–52. doi: 10.1210/en.2003-1239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liu R, Desta T, He H, Graves DT. Diabetes alters the response to bacteria by enhancing fibroblast apoptosis. Endocrinology. 2004;145:2997–3003. doi: 10.1210/en.2003-1601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liu R, Bal HS, Desta T, Krothapalli N, Alyassi M, Luan Q, et al. Diabetes enhances periodontal bone loss through enhanced resorption and diminished bone formation. J Dent Res. 2006;85:510–4. doi: 10.1177/154405910608500606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schmidt AM, Weidman E, Lalla E, Yan SD, Hori O, Cao R, et al. Advanced glycation endproducts (AGEs) induce oxidant stress in the gingiva: A potential mechanism underlying accelerated periodontal disease associated with diabetes. J Periodontal Res. 1996;31:508–15. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0765.1996.tb01417.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Aiello LP, Wong JS. Role of vascular endothelial growth factor in diabetic vascular complications. Kidney Int Suppl. 2000;77:S113–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2000.07718.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Unlü F, Güneri PG, Hekimgil M, Yesilbek B, Boyacioglu H. Expression of vascular endothelial growth factor in human periodontal tissues: Comparison of healthy and diabetic patients. J Periodontol. 2003;74:181–7. doi: 10.1902/jop.2003.74.2.181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gross JL, Moscatelli D, Rifkin DB. Increased capillary endothelial cell protease activity in response to angiogenic stimuli in vitro. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1983;80:2623–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.80.9.2623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zoellner H, Hunter N. The vascular response in chronic periodontitis. J Oral Pathol Med. 1994;39:93–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1834-7819.1994.tb01380.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bonakdar MP, Barber PM, Newman HN. The vasculature in chronic adult periodontitis: A qualitative and quantitative study. J Periodontol. 1999;68:50–8. doi: 10.1902/jop.1997.68.1.50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pinchback JS, Taylor BA, Gibbins JR, Hunter N. Microvascular angiopathy in advanced periodontal disease. J Pathol. 1996;179:204–9. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9896(199606)179:2<204::AID-PATH552>3.0.CO;2-N. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Johnson RB, Serio FG, Dai X. Vascular endothelial growth factors and progression of periodontal diseases. J Periodontol. 1999;70:848–52. doi: 10.1902/jop.1999.70.8.848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sakallioglu EE, Ayas B, Sakallioglu U, Yavuz U, Açikgöz G, Firatli E. Osmotic pressure and vasculature of gingiva in experimental diabetes mellitus. J Periodontol. 2007;78:757–63. doi: 10.1902/jop.2007.060332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]