Abstract

Background:

The width of attached gingiva varies from tooth to tooth and also among individuals with mixed opinions regarding an “adequate” or “sufficient” dimension of the gingiva. Although the need for a so-called adequate amount of keratinized tissue for maintenance of periodontal health is questionable, the mucogingival junction serves as an important clinical landmark in periodontal evaluation. There are various methods of locating the mucogingival junction namely the functional method and the visual method with and without histochemical staining, which aid in the measurement of the width of attached gingiva.

Materials and Methods:

This study was carried out to assess the full mouth mid-buccal width of attached gingiva in individuals of four different age groups. This study also evaluated the difference in visual and histochemical methods in identification of the mucogingival junction to calculate the width of attached gingiva.

Results:

It was seen that the width of attached gingiva increases with age, and there was no significant difference in the width of attached gingiva by both the methods.

Conclusion:

Width of attached gingival varies in different areas of the mouth and also increases with age with no significant difference in the method of its assessment.

Keywords: Histochemical staining, mucogingival junction, width of attached gingiva

INTRODUCTION

Oral mucosa consists of three zones namely the gingiva and hard palate, termed the masticatory mucosa; the dorsum of the tongue (specialized mucosa) and the oral mucous membrane (lining mucosa). Macroscopically, the gingiva is divided into marginal, attached and interdental areas.[1] Orban[2] first described the term attached gingiva as that part of the gingiva that is firmly attached to the underlying tooth and bone and is stippled on the surface.[2]

The width of attached gingiva is the distance between the mucogingival junction to projection of the external surface of the bottom of the sulcus or the periodontal pocket.[1] Despite various opinions regarding the adequate amount of keratinized tissue for maintenance of periodontal health, the mucogingival junction serves as an important clinical landmark in periodontal evaluation.[3] The mucogingival junction is a discrete line distinguishing the movable and immovable mucosa during passive motion of the lip and cheek.[4] The methods employed for locating the mucogingival junction are the visual method (VM), functional method (FM), VM after histochemical staining method (HM).[5] VM assessment is based on the color difference between the gingiva and alveolar mucosa.[2] In the FM, mucogingival junction is assessed as a borderline between the movable and immovable tissue wherein tissue mobility is determined by running a periodontal probe positioned horizontally from the vestibule toward the gingival margin with light pressure.[4] The mucogingival junction can be assessed visually after the staining the mucogingival complex with Lugol's iodine solution based on the difference in the glycogen content. The alveolar mucosa differs from keratinized gingiva histochemically in its glycogen content, acid phosphatase and nonspecific esterase content and an increased amount of elastic fiber content within the corium resulting in an iodo-positive reaction.[6,7,8,9] The attached gingiva, which is keratinized, has no glycogen in the most superficial layer and gives an iodo-negative reaction. Thus, Lugol's iodine solution stains only the alveolar mucosa and clearly demarcates the mucogingival junction.

Aims and objectives

The aims and objectives of this study were to assess the full mouth mid-buccal width of attached gingiva and evaluate the difference in visual and histochemical methods in identification of the mucogingival junction to calculate the width of attached gingiva.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Source of data

A total of 60 patients (n = 60) were selected from the out-patient Department of Institute of Dental Studies and Technologies, Modinagar based on the following inclusion and exclusion criteria. Patients till the age of 60 years with good general health, healthy gingival tissues (no loss of attachment) and those who had not taken any sort of periodontal treatment in the last 6 months were included in the study. Pregnant and lactating females, patients with systemic illnes and those taking medications that may have an influence on the gingiva were excluded.

METHODS

The patients were informed about the study protocol and those, who agreed for the study, were finally included. Based on the age of the patient, they were categorized into one of the following groups:

1–14 years

15–30 years

30–45 years

Greater than 45 years.

The iodine solution (Lugol's solution) was prepared by diluting 2 g of potassium iodide and 1 g of iodine crystals in 60 ml of distilled water.[10] The entire procedure was conducted by a single examiner. All the measurements were made on all teeth at the mid-buccal area. To assess the width of attached gingiva the mucogingival junction was demarcated by the following methods:

Method 1: VM [Figure 1]

Method 2: VM after HM - the solution was burnished with a cotton pellet using light pressure on the subject's gingiva and alveolar mucosa till a sharp demarcation between keratinized tissue and alveolar mucosa was distinct [Figure 2].

Figure 1.

Visual method of demarcating the mucogingival junction

Figure 2.

Histochemical staining method of demarcating the mucogingival junction

Width of keratinized gingiva was measured as the distance from the gingival margin to the mucogingival junction. Sulcus depth was measured as the distance from the gingival margin to base of the sulcus. With these values, the width of attached gingiva was calculated as a difference of the sulcus depth from the width of the keratinized tissue. All data collected were subjected to statistical analysis for the comparison of the readings by both the methods.

RESULTS

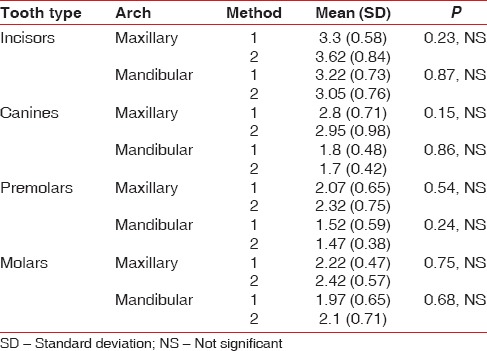

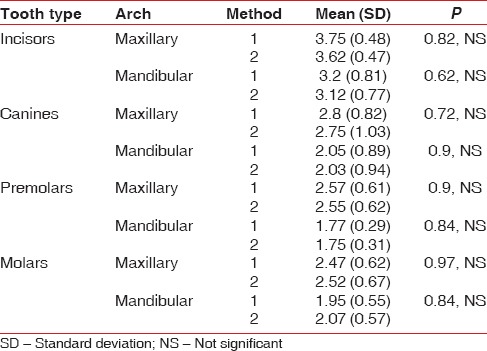

A total of 60 subjects participated in the study with 15 subjects in each group. The assessment of width of attached gingiva in different age groups by VM revealed that the width of gingiva increases with age wherein the mean width in maxillary teeth in <14 years was 1.89 mm, which increased to 2.11 (15-30years) and 2.9 (31-45years) and 3.11 mm in the age group of 45–60 years. Similarly, in the mandibular teeth the mean width in <14 years was 1.5 mm, increased to 2.1 mm (15-45 years) and 2.24 mm in the age group of 45–60 years [Table 1]. Assessment of width of attached gingiva in different age groups by visual and HM showed a mean of 2.05 mm in <14 years and 3.11 mm in 45–60 years age in maxillary teeth. In the mandibular teeth, the mean in <14 years was 1.57 mm and 2.31 mm in the age group of 45–60 years [Table 2]. There was no significant difference in the width of attached gingiva in both maxillary and mandibular teeth in age group of <14 years irrespective of the method used for its assessment [Table 3]. Comparison by two different methods in various tooth types in age group 15–30 years revealed no significant results although the widest zone of attached gingiva was found in the incisors by both the methods (method 1; 4.07, method 2; 3.85) and the least in the premolar region (method 1; 1.92, method 2; 2.07). These variations were similar in the mandibular teeth also [Table 4]. Similar trends of maximum width in the maxillary incisors and least in the mandibular premolars were noticed in the other age groups, that is, 31–45 years and 46–60 years with no significant difference seen in the two methods [Tables 5 and 6].

Table 1.

Assessment of width of attached gingiva in different age groups by visual method 1

Table 2.

Assessment of width of attached gingiva in different age groups by visual after histochemical staining method 2

Table 3.

Comparison by two different methods in age group of <14 years

Table 4.

Comparison by two different methods in various tooth types in age group 15-30 years

Table 5.

Comparison by two different methods in various tooth types in age group 31-45 years

Table 6.

Comparison by two different methods in various tooth types in age group 46-60 years

DISCUSSION

Assessment of the width of attached gingiva is vital in assessing the risk of periodontium to be affected by disease. In the assessment of width of gingiva, the mucogingival junction serves as an important anatomical landmark, which can be demarcated by various methods. As suggested by Fasske and Morgenroth the precise location of this junction can be visualized after staining with stains like Lugol's iodine that aid in determining the exact point at which the keratinization ends.[11] The mid-buccal region was chosen as it is easily accessible and convenient. In order to eliminate probing discrepancies all the measurements were carried out by a single examiner and in subjects with clinically healthy gingiva as factors like probe dimension, probing force and inflammation of the tissues are known to alter the measurements (Listgarten 1980).[12] The assessment of width of attached gingiva in different age groups by VM revealed that the width of gingiva increases with age as suggested by authors like Ainamo and Talari[13] and Vincent et al.[14] The width of attached gingiva varies in different areas of the mouth and have been given a range of 1–9 mm,[15] 1–4 mm,[16] 0–g5 mm.[17] In the present study, the range of the mean width of attached gingiva varied from 1 mm to 4 mm. Similar to the variations seen in Bower's study, the widest zone of attached gingiva was found in the incisors and the least in the premolar region irrespective of the method used in the assessment.[15] The categorization of various tooth types was done only in the last three age groups and not in the age group of less than 14 years as in all the fifteen subjects of this group, each subject would have a different configuration of teeth present. So in cases of mixed dentition it was not possible to tabulate based on the tooth type. The results of the present study showed that there was no significant difference in the measurements whether the visual or visual after HM was used. These results are in accordance with the study conducted by Guglielmoni et al.[5] while in contrast with those reported by Bernimoulin et al.[18] who stated that the FM resulted in the greatest width of keratinized gingiva. Furthermore, the VM after HM resulted in the slightest inter and intra-examiner discrepancy when compared with visual and FMs. The dissimilar results may partially be due to different tooth and site selection.

CONCLUSION

Assessment of full mouth mid-buccal width of attached gingiva revealed different widths in various areas of the mouth with the maxillary incisors having the greatest width and the mandibular premolars the least width. Furthermore, there was no substantial, consistent variance in the method of assessing the mucogingival junction. However, a larger sample size and more studies need to be carried out to get a definitive range which can be defined as adequate or inadequate thereby making treatment options easier.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Fiorellini JP, Kim DM, Ishikawa SO. Thegingiva. In: Newman MG, Takei H, Klokkevold PR, Carranza FA, editors. Carranza's Clinical Periodontology. 10th ed. Missouri: Saunders Publishers; 2006. pp. 46–7. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Orban B. Clinical and histologic study of the surface characteristics of the gingiva. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1948;1:827–41. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(48)90014-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wennström JL, Zucchelli G, Pini GP. Mucogingival therapy-periodontal plastic surgery. In: Lindhe J, Lang NP, Karring T, editors. Clinical Periodontology and Implant Dentistry. 5th ed. Oxford: Blackwell Munksgaard Publishers; 2008. pp. 956–7. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hilming F, Jervoe P. Surgical extension of vestibular depth. On the results in various regions of the mouth in periodontal patients. Tandlaegebladet. 1970;74:329–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Guglielmoni P, Promsudthi A, Tatakis DN, Trombelli L. Intra- and inter-examiner reproducibility in keratinized tissue width assessment with 3 methods for mucogingival junction determination. J Periodontol. 2001;72:134–9. doi: 10.1902/jop.2001.72.2.134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Weinmann JP, Meyer J, Mardfin D, Weiss M. Occurrence and role of glycogen in the epithelium of the alveolar mucosa and of the attached gingiva. Am J Anat. 1959;104:381–402. doi: 10.1002/aja.1001040304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lozdan J, Squier CA. The histology of the muco-gingival junction. J Periodontal Res. 1969;4:83–93. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0765.1969.tb01950.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kapur KK, Chauncey HH, Shapiro S, Shklar G. A comparative study of the enzyme histochemistry of human edentulous alveolar mucosa and gingival mucosa. Periodontics. 1963;1:137–47. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tencate AR. The distribution of acid phosphatase, non-specific esterase and lipid in oral epithelia in man and the macaque monkey. Arch Oral Biol. 1963;8:747–53. doi: 10.1016/0003-9969(63)90006-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sheehan DC, Hrapchak BB. Staining and labelling-laboratory manuals. In: Sheehan DC, Hrapchak BB, editors. Theory and Practice of Histotechnology. 2nd ed. St. Louis: CV Mosby Publishers; 1980. p. 219. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fasske E, Morgenroth K. Comparitive stomatoscopic and histochemical studies of the marginal gingiva in man. Parodontologie. 1958;12:151–60. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Listgarten MA. Periodontal probing: What does it mean? J Clin Periodontol. 1980;7:165–76. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1980.tb01960.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ainamo J, Talari A. The increase with age of the width of attached gingiva. J Periodontal Res. 1976;11:182–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0765.1976.tb00069.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vincent JW, Machen JB, Levin MP. Assessment of attached gingiva using the tension test and clinical measurements. J Periodontol. 1976;47:412–4. doi: 10.1902/jop.1976.47.7.412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bowers GM. A study of the width of attached gingiva. J Periodontol. 1963;34:201–9. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jacob P, Zade RM. Width of attached gingiva in an Indian population: A descriptive study. Bangladesh J Med Sci. 2009;8:1–4. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Subbaiah R, Manohar B. Assessment of the width of attached gingiva in different regions of the mouth in an Indian subpopulation. J Indian Dent Assoc. 2012;6:96–8. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bernimoulin JP, Son S, Regolati B. Biometric comparison of three methods for determining the mucogingival junction. Helv Odontol Acta. 1971;15:118–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]