Abstract

Background:

The periodontal diseases are the most prevalent oral diseases worldwide especially in developing countries like India. The objective of this cross-sectional survey was to determine the prevalence of periodontal diseases and treatment needs (TNs) in a hospital-based population.

Materials and Methods:

Totally, 500 men and women (15-74 years) were recruited and periodontal status of each study subject and sextant was evaluated on the basis of community periodontal index of TNs, and thereafter TN for each subject and sextant was categorized on the basis of the highest code recorded during the examination.

Results:

A total of 500 subjects (59% males and 41% females) was divided into seven age groups, that is, 15-19, 20-24, 25-34, 35-44, 45-54, 55-64, and 65-74 years and sextants were included from the 486 subjects. Healthy periodontium, bleeding on probing, calculus, shallow pockets, and deep pockets were found in 3.9%, 6.58%, 50.61%, 20.98%, and 17.90% subjects, respectively. Males were more affected with shallow and deep pockets as compared to females. Periodontal diseases in the early stages were more prevalent in the younger age groups, whereas advanced stages were more prevalent in older age groups. 17.90% subjects and 11.48% sextants need complex treatment. About 77.98% subjects and 73.15% sextants require either oral hygiene instructions or oral hygiene instructions and oral prophylaxis. Only 3.9% subjects and 15.36% sextants were healthy and needed no treatment.

Conclusions:

Periodontal diseases were found to be 96.30% in the study population and the results indicate that majority of the population need primary and secondary level of preventive program to reduce the chances of initiation or progression of periodontal diseases thereby improving their systemic health overall.

Keywords: Community periodontal index of treatment needs, periodontal disease, prevalence

INTRODUCTION

The periodontal diseases are the most prevalent oral diseases worldwide especially in developing countries like India. General unawareness, infrequent dental visits, lower socioeconomic status, and illiteracy have contributed to its high prevalence.[1] Gingivitis and periodontitis are chronic inflammatory disorders of periodontal tissues, that is, gingival, periodontal ligament, cementum, and alveolar bone surrounding the tooth. Microorganisms present in the dental plaque are the main etiologic factors responsible for initiation and progression of periodontal diseases.[2] Gingivitis is the inflammation of soft tissue and may occur on a periodontium with no attachment loss or on a periodontium with stable and attachment loss that is not progressing. Periodontitis is the inflammation of the supporting tissues of the teeth resulting in the progressive destruction of soft and hard tissues and clinically represented by the pocket formation, gingival recession, or both.[3] The periodontal diseases are considered as major health concern as these are also the risk factors for many systemic diseases, that is, cardiovascular disease, preterm low birth weight infants, respiratory disease, diabetes mellitus, and cerebral infarction or cerebral stroke.[1,4]

The community periodontal index of treatment needs (CPITN) is a type of periodontal index developed by the “joint working committee” of the “World Health Organization” and the “Federation Dentaire Internationale.”[5] The majority of previous surveys have used the CPITN index in the estimation of prevalence of periodontal disease and treatment needs (TNs).[6,7,8,9,10,11] A prevalence study is also known as cross-sectional study, a simplest form of the observational study and is more useful for chronic rather than short-lived diseases. Prevalence of a disease refers specifically to all current cases (old and new) existing at a given point of time.[12] In India, many epidemiologic studies have been carried out to estimate the periodontal diseases[7,8,9,10,11,13,14,15,16] but to the best of our knowledge, there is no reported prevalence study in the literature to estimate the periodontal disease and TNs in Varanasi in India and its proximal areas. Therefore, the present cross-sectional survey is designed with the objective to determine the distribution and severity of periodontal diseases and TNs in a hospital-based population attending the dental out-patient department, Sir Sunderlal Hospital, Banaras Hindu University, Varanasi, India, which covers the population coming from various districts of eastern part of Uttar Pradesh and Bihar.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

In the present cross-sectional study, 500 volunteer subjects in the age group ranging from 15 years to 74 years of any gender were recruited from the dental OPD, Sir Sunderlal hospital, Institute of Medical Sciences, Banaras Hindu University, Varanasi, India. This is a tertiary hospital serving the population of the eastern part of northern India.

Inclusion criteria

Age 15-74 years.

No periodontal therapy in the last 6 month.

Systemically healthy patients.

Exclusion criteria

Acute oral disease.

Antimicrobial therapy for 1-month prior to the study.

Structure pretested schedule included the age, gender, address, medical history, history of periodontal therapy, and history of antimicrobial therapy. Periodontal status and Tns of each study subject and sextant were evaluated on the basis of CPITNs that was recorded by a single trained examiner using the dental chair and adequate light. Mouth mirror and WHO probe were used in the study for the examination. The WHO probe has the working tip (ball) of 0.5 mm in diameter and markings at interval of 3.5, 2.0, 3.0, and 3.0 mm (total 11.5 mm) from the working tip with black color coding between 3.5 and 5.5 mm. The ball helps in the detection of calculus, rough margins of restorations or any other irregularities on the tooth surface and reduces the chances of false measurement of the pocket depth.[17] The WHO probe tip is inserted between the tooth surface and lateral wall of the gingival sulcus and walked around the tooth to determine the pocket depth, subgingival calculus, and bleeding response. The examined sites per tooth were mesial, mid-line and distal on both facial and lingual or palatal surfaces. The dentition was divided into six sextants. The third molars were not included except where they function in place of second molars. Ten index teeth, that is, 17, 16, 11, 26, 27, 37, 36, 31, 46, and 47 were examined in subjects aged 20 years or above. Under the age of 19 years, six index teeth, that is, 16, 11, 26, 36, 31, 46 were examined. Second molars were excluded as index teeth in young subjects up to the age of 19 years to eliminate the false scoring due to pseudopocket formation during eruption of teeth.[17,18]

A code was given to each sextant, but only highest code was recorded among the examined teeth in individual sextant. After evaluating the periodontal status, TN for each subject was categorized on the basis of the highest code recorded during the examination of all sextants in that subject. The examined sextants were also categorized into the TN groups according to their highest code number. Subjects and the sextants were categorized into the different TN groups such as TN − 0= no treatment (Code 0), TN − 1= oral hygiene instructions (Code 1), TN − 2= oral hygiene instructions + oral prophylaxis and removal of plaque retentive factors (Code 2 and 3) and TN − 3= oral hygiene instructions + oral prophylaxis and removal of plaque retentive factors + complex treatment (Code 4).[17,18]

Statistical analysis

Hospital-based clinical data were presented in the form of number and percentage through tables and graphs. Statistical analysis was done by SPSS Version 16.0 which is manufactured by IBM Corporation, New York, United States

RESULTS

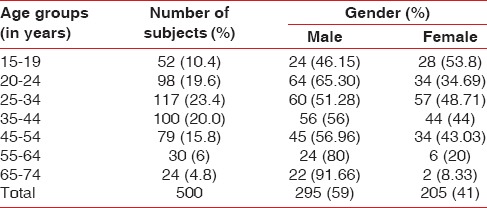

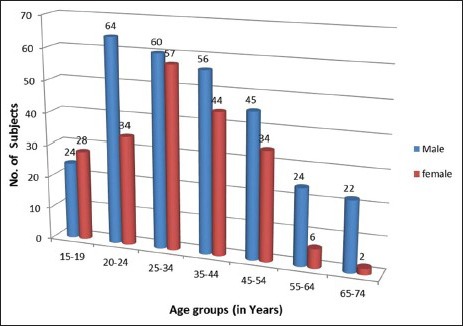

Among the 500 subjects recruited in the present study, 295 (59%) males and 205 (41%) females were divided into seven age groups, that is, 15-19, 20-24, 25-34, 35-44, 45-54, 55-64, and 65-74 years. Males were more in all age groups except 15-19 years. 25-34 years age group shows the maximum no. of subjects to be examined [Table 1 and Graph 1].

Table 1.

Age- and gender-wise distribution of subjects

Graph 1.

Age- and gender-wise distribution of subjects

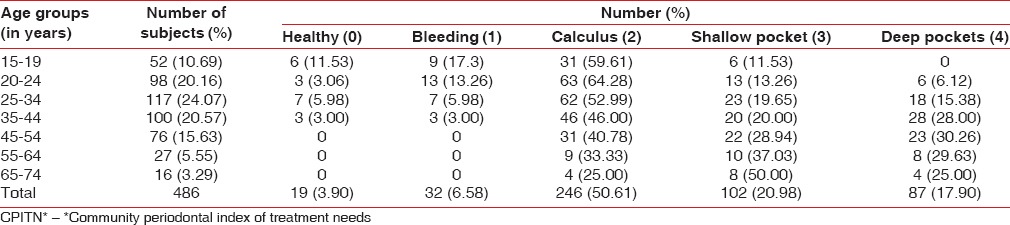

Table 2 shows the age-wise distribution of subjects according the highest code of CPITN index among the examined sextants in a person. Of 500 subjects, 486 subjects had teeth in functional condition in a sextant and 14 subjects were either completely edentulous or not fulfill the conditions of CPITN index. Only 19 (3.9%) subjects in all age groups had healthy teeth with the highest percentage in 15-19 years age group and no person had healthy teeth after 44 years. 32 (6.58%) subjects had bleeding on probing. 246 (50.61%) subjects had calculus on the teeth. 102 (20.98%) persons had shallow pockets that were increased as the age increases. 87 (17.90%) subjects had deep pockets that were maximum in 45-54 years age group thereafter decreased.

Table 2.

Age-wise distribution of subjects according to the highest code of CPITN* index

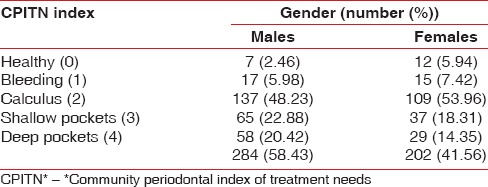

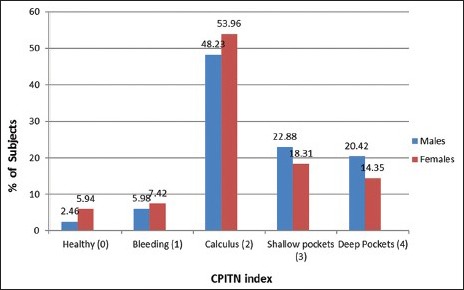

Table 3 and Graph 2 show the gender-wise distribution of subjects according to CPITN index. Males were more affected with shallow and deep pockets as compared to females who had higher scores of healthy teeth, bleeding on probing and calculus conditions.

Table 3.

Gender-wise distribution of subjects according to the highest code of CPITN* index

Graph 2.

Gender-wise distribution of subjects according to the highest code of community periodontal index of treatment need index

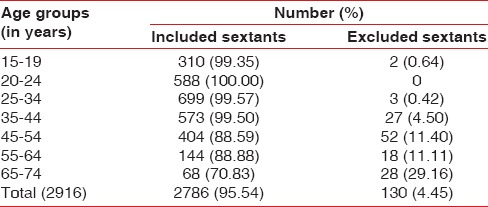

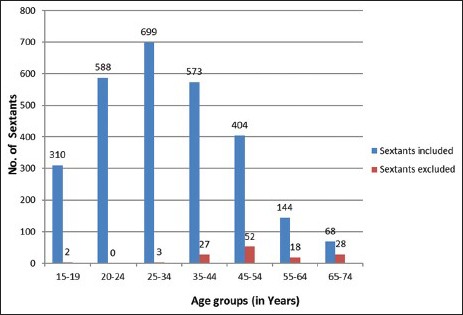

Table 4 and Graph 3 show the distribution of included and excluded sextants in different age groups. 2786 (95.54%) sextants were included, and 130 (4.45%) sextants were excluded from 486 subjects in the study. Maximum sextants were excluded in the age group of 65-74 years, and none was excluded in the age group of 20-24 years. Negligible sextants were excluded in the age groups of 15-19 and 25-34 years.

Table 4.

Distribution of included and excluded sextants in different age groups

Graph 3.

Distribution of included and excluded sextants in different age groups

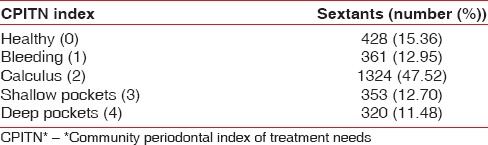

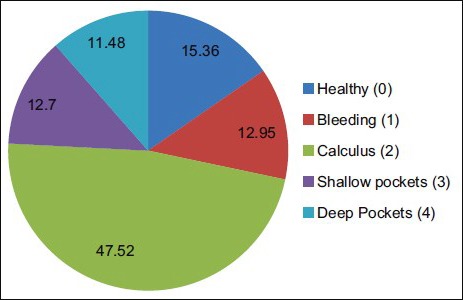

Among the 2786 sextants, calculus (Code 2) was found in 1324 (47.52%) sextants as their highest score and healthy periodontium (Code 0) was found in 428 (15.39%) sextants. Others codes, that is, 1, 3, and 4 had approximately equal distribution of sextants, that is, 361 (12.95%), 354 (12.70%), and 320 (11.48%), respectively [Table 5 and Graph 4].

Table 5.

Distributions of sextants according to CPITN* index

Graph 4.

Distribution of sextants according to community periodontal index of treatment needs

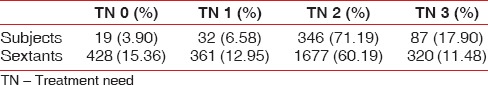

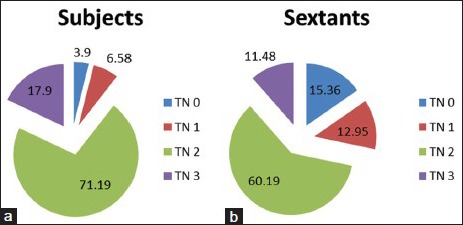

Subjects and sextants were distributed in TN groups on the basis of the highest code of CPITN index. 87 (17.90%) subjects and 320 (11.48%) sextants need oral hygiene instructions, oral prophylaxis, and complex treatment (TN 3). 346 (71.19%) subjects and 1677 (60.19%) sextants need oral hygiene instructions and oral prophylaxis (TN 2). 32 (6.58%) subjects and 361 (12.95%) sextants need oral hygiene instructions. Only 19 (3.9%) subjects were healthy and needed no treatment, whereas 428 (15.36%) sextants were healthy and needed no treatment [Table 6 and Graph 5a and b].

Table 6.

Distributions of subjects and sextants according to TNs

Graph 5.

Distribution of subjects (a) and sextants (b) according to treatment needs

DISCUSSION

The present cross-sectional prevalence study aimed to assess the prevalence of periodontal disease and the TNs of the subjects those visited to the dental OPD, Sir Sunderlal Hospital, Institute of Medical Sciences, Banaras Hindu University, Varanasi, India, a tertiary hospital. Of the 500 subjects, 486 subjects had teeth in functional condition, and 14 subjects were either completely edentulous or not fulfill the conditions of CPITN index. Healthy periodontium was found in 19 (3.9%) subjects with the highest percentage in 15-19 years age group and after 44 years no person had healthy teeth.

In the present study, the prevalence of periodontal disease was found to be 96.30%. Periodontal diseases in the early stages were more prevalent in the younger age groups as compared to advanced stages that were more prevalent in older age groups. Calculus was present in 246 (50.61%) subjects that is most frequently observed periodontal condition. Deep pockets were found in 87 (17.90%) subjects that increased as the age advanced up to 45-54 and decreased thereafter. The reason behind this finding might be that CPITN index is based on the measurement of pocket depth and does not record the gingival recession.[18] Therefore, it may not provide the true extension of periodontal disease. Although it is most frequently used index in the assessment of periodontal disease being a simple, easy, and having international uniformity for screening the population at large scale.[18] Overall, prevalence and severity of periodontal disease increases with age that is similar with other published studies which have shown that increasing severity of periodontal diseases is due to the untreated cumulative effect of disease process over a period of time instead of ageing process.[19,20,21] Males were more affected with moderate and severe periodontitis as compared to females that is also consistent with the other reported studies.[10,22] The factors responsible for this finding may be that males are less health conscious and have poorer oral hygiene than females due to heavy deposition of plaque and calculus.[22,23] There is difficulty in comparing the data of such observational studies because the results depend upon several factors such as, study designs, sample size, eligibility criteria, recording of data, criteria for assessment of disease, microbial pathogens, disease activity and multifactorial nature of periodontal diseases including age, gender, socioeconomic status, educational status, stress and genetic factors and control of these factors is challenging.

A total of 2786 (95.54%) sextants was included and 130 (4.45%) sextants were excluded from the 486 subjects. Maximum sextants were excluded in the age group of 65-74 years due to either partially edentulism or absence of functional teeth due to periodontal disease or dental caries. Few sextants were excluded in the age group of 15-19, 20-24, and 25-34 years that was due to the history of trauma at a young age. Calculus (code 2) was found in the maximum number of sextants similar to subjects.

In the present study, the findings suggest that only 17.90% subjects and 11.48% sextants need complex treatment. On the other hand, approximately 77.98% subjects and 73.15% sextants require either oral hygiene instructions or oral hygiene instructions or oral prophylaxis. Only 3.9% subjects and 15.36% sextants were healthy and needed no treatment. Finally, the results indicates that majority of the population need primary and secondary level of preventive program to educate, motivate and instruct people about oral hygiene maintenance and provide the treatment in its early stages to reduce the chances of initiation or progression of periodontal diseases.

CONCLUSION

Periodontal diseases were found to be 96.30% (highly prevalent) in the study population, and most participants required oral hygiene instructions and oral prophylaxis. To prevent or minimize the progression of the disease, more number of oral health surveys will help in planning of preventive health program at large scale in the beneficence of the society. Qualitative research should be done for welfare of community through “systematic science and community” programs and improved oral health literacy, community education, community-based interventions, and accessible dental services at the primary or community health centers should also be provided to improve the oral as well as systemic health.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Page RC, Beck JD. Risk assessment for periodontal diseases. Int Dent J. 1997;47:61–87. doi: 10.1111/j.1875-595x.1997.tb00680.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zambon JJ. Periodontal diseases: Microbial factors. Ann Periodontol. 1996;1:879–925. doi: 10.1902/annals.1996.1.1.879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Novak MJ. Classification of diseases and conditions affecting the periodontium. In: Newman MG, Takei HH, Carranza FA, editors. Clinical Periodontology. 9th ed. Philadelphia: Saunders Publishers an Imprint of Elsevier Science; 2003. pp. 64–73. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mealey BL. Influence of periodontal infections on systemic health. Periodontol 2000. 1999;21:197–209. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0757.1999.tb00176.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ainamo J, Barmes D, Beagrie G, Cutress T, Martin J, Sardo-Infirri J. Development of the World Health Organization (WHO) community periodontal index of treatment needs (CPITN) Int Dent J. 1982;32:281–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kumar TS, Dagli RJ, Mathur A, Jain M, Balasubramanyam G, Prabu D, et al. Oral health status and practices of dentate Bhil adult tribes of southern Rajasthan, India. Int Dent J. 2009;59:133–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Acharya S, Bhat PV. Oral-health-related quality of life during pregnancy. J Public Health Dent. 2009;69:74–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-7325.2008.00104.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ranganathan K, Magesh KT, Kumarasamy N, Solomon S, Viswanathan R, Johnson NW. Greater severity and extent of periodontal breakdown in 136 south Indian human immunodeficiency virus seropositive patients than in normal controls: a comparative study using community periodontal index of treatment needs. Indian J Dent Res. 2007;18:55–59. doi: 10.4103/0970-9290.32420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Joshi NV, Marawar PP. Periodontal health status of rural population of Ahmed Nagar Distic, Maharashtra using CPITN inducing system. J Indian Soc Periodontol. 2004;7:115–7. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Madden IM, Stock CA, Holt RD, Bidinger PD, Newman HN. Oral health status and access to care in a rural area of India. J Int Acad Periodontol. 2000;2:110–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Joseph PA, Cherry RT. Periodontal treatment needs in patients attending dental college hospital, Trivendrum. J Indian Soc Periodontol. 1996;20:67–71. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Park K. Principles of epidemiology and epidemiologic methods. In: Park K, editor. Preventive and Social Medicine. 20th ed. Jabalpuri: Banarsidas Bhanot Publishers; 2009. pp. 49–122. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Singh A, Agarwal V, Tuli A, Khattak BP. Prevalence of chronic periodontitis in Merrut: a cross-sectional survey. J Indian Soc Periodontol. 2012;16:529–32. doi: 10.4103/0972-124X.106895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jagedeeran M, Rotti SB, Danabolan M. Oral health status and risk factors for dental and periodontal diseases among rural women in Pondicherry. Indian J Comm Med. 2000;25:31. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Singh S, Gupta ND, Sharma AK, Bay A. Periodontal health status of rural and urban population of Aligarh district of Uttar Pradesh state. J Indian Soc Periodontol. 2005;9:86–90. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shah N, Sundaram KR. Impact of socio-demographic variables, oral hygiene practices and oral habits on periodontal health status of Indian elderly: a community-based study. Indian J Dent Res. 2003;14:289–97. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Willkins EM. Indices and scoring methods. In: Willkins EM, editor. Clinical Practice of the Dental Hygienist. 9th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins Publisher; 2004. pp. 323–45. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Peter S. Indices used in dental epidemiology. In: Peter S, editor. Essentials of Preventive and Community Dentistry. 1st ed. New Delhi: Arya (Medi) Publishing House; 1999. pp. 456–552. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Burt BA. Periodontitis and aging: reviewing recent evidence. J Am Dent Assoc. 1994;125:273–9. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.1994.0034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Papapanou PN. Risk assessments in the diagnosis and treatment of periodontal diseases. J Dent Educ. 1998;62:822–39. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Agarwal V, Khatri M, Singh G, Gupta G, Marya CM, Kumar V. Prevalence of periodontal diseases in India. J Oral Health Community Dent. 2010;4:7–16. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Novak KF, Novak MJ. Risk assessment. In: Newman MG, Takei HH, Carranza FA, editors. Clinical Periodontology. 9th ed. Philadelphia: Saunders Publishers an Imprint of Elsevier Science; 2003. pp. 469–74. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Abdellatif HM, Burt BA. An epidemiological investigation into the relative importance of age and oral hygiene status as determinants of periodontitis. J Dent Res. 1987;66:13–8. doi: 10.1177/00220345870660010201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]