Abstract

Immune mediated diseases of oral cavity are uncommon. The lesions may be self-limiting and undergo remission spontaneously. Among the immune mediated oral lesions the most important are lichen planus, pemphigus, erythema multiformi, epidermolysis bullosa, systemic lupus erythematosis. Cellular and humoral mediated immunity play a major role directed against epithelial and connective tissue in chronic and recurrent patterns. Confirmatory diagnosis can be made by biopsy, direct and indirect immunoflouresence, immune precipitation and immunoblotting. Therapeutic agents should be selected after thorough evaluation of immune status through a variety of tests and after determining any aggravating or provoking factors. Early and appropriate diagnosis is important for proper treatment planning contributing to better prognosis and better quality of life of patient.

KEY WORDS: Immunoflourescence, lichenplanus, pemphigus

Immune-mediated diseases along with lesions in oral cavity. Immunology is defined as the study of the molecular cells, organs and system for the recognition and disposal of foreign materials.[1] Factor responsible for differences in immunity are age, nutrition and genetic factors. Clinical appearance may not lead to a final diagnosis, but can be achieved by a biopsy of 4 mm in diameter at the perimeter.[2]

Classification

Hypersensitive reaction

Pemphigus vulgaris

Paraneoplastic pemphigus

Cicatricial or mucocutaneouspemphigoid

Cutaneous, bullous pemphigoid

LinearIgA

Epidermolysisbullosa

Lichenplanus

Erythemamultiforme

Systemic drug reaction

Lupus erythematosus

Scleroderma

Crest syndrome

Bechets syndrome

Reiter's syndrome.[3]

Hypersensitve Reaction

Mucosal surfaces are exposed to many dietary proteins and infectious agents, the immune system normally will not react to these antigens. Unresponsiveness or tolerance to these antigens are maintained by three principle mechanism namely energy or functional unresponsiveness; apoptosis; and immune suppression by regulatory T-cells.[4]

Anaphylaxis is the most serious hypersensitive reaction, which commences immediately after the exposure to allergens. The clinical presentation may be redness or whiteness of mucosa, swelling of lips, tongue, cheek or ulcers and blisters.

Lichen planus

Lichen planus is believed to result from an abnormal T-cell mediated immune response in which basal epithelial cells are recognized as foreign because of changes in the antigenicity of cell surface.[5] The reticular type is most common type of oral lichen planus. It presents as interlacing white keratotic lines with an erythematous border. The striae are typically located bilaterally on the buccal mucosa, mucobuccal fold, gingiva. Erosive lichen planus is second most common type. The differential diagnosis of erosive lichen planus includes squamous cell carcinoma, discoid lupus erythematosus, chroniccandidiasis, benign mucous membrane pemphigoid, lichenoid reactions.[6]

Histopathology represents liquefaction of the basal cell layer accompanied by apoptosis of the keratinocytes, dense band like lymphocytic infiltrate at the interface between the epithelium and connective tissue. A characteristic saw-toothed reteridges, civatte bodies, which represent degenerating keratinocytes, are viewed in the lower half of the surface epithelium.

Diagnosis is based on histopathology, however erosive type is challenging. Treatment needs excellent oral hygiene, which will minimize the severity of symptoms, topical corticosteroids to the modulate immune response. Other treatment modalities include retinoids, Vitamin A analogs, cyclosporine rinse, immunomodulating agent levamisole psoralens and long wave ultraviolet A treatment.[7]

Pemphigus Vulgaris

Pemphigus Vulgaris is an autoimmune blistering disease involving skin and mucosal membrane. The pathogenesis behind is that the formation of autoantibodies to the desmosomes involved in the cell-cell adhesion leads to destruction of cellular cohesion.[1]

Intradermal blistering results in the epithelium where desmoglein one and three are present. Oral lesions are the first manifestations of the disease in 50–90% of cases. Blisters localize in any part of oralmucosa but frequently subjected to frictional areas such as the soft palate, buccal mucosa, ventral tongue, gingival and lower lip. Blisters rupture leading to chronic painful ulcer and erosions that take a long window for healing. Diagnosis is on three major criteria, that is, clinical features, histology and immunological.[8] Another diagnostic approach is to test for the nikolskys sign. Laboratory methods for diagnosis include tzanck smear to detect acantholytic cells. Histology of fresh blister specimen aids in detecting the accantholysis in the stratiformspinous layer.

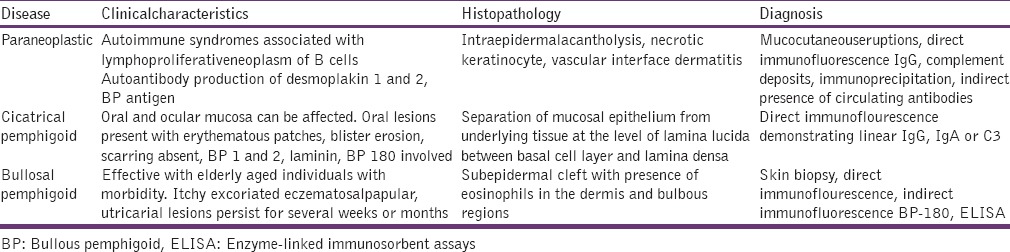

Direct immunoflourescence helps in detecting intercellular deposits of IgGMA and C3 protein. Indirect immunoflourescenceaids to detect pemphigus antibodies in serum. Immunoprecipitation and immunoblotting techniques confirm, where others are in doubt [Table 1].[9]

Table 1.

Diagnostic criteria

Linear IgA

It is an acquired blistering disorder which is of two types one of which is chronic dermatitis of childhood, occurring within the first 10 years and adult linear IgA occurring later between 60 and 65 years. Both of them share the target lesions. Human leukocyte antigen-B8 has been associated with childhood IgA. Laboratory investigation reveals elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate. Lesions resolve with scarring. Histological appearance seems to show micro abscess and infiltration of eosinophilic in superficial corneum. Lymphocytes are seen surrounding small vessels. Diagnosis is based on immunoflouresence.[10]

Epidermolysis Bullosa

It is a developmental blister disease with reversal pressure, ring shaped atrophic scars on the surface of the limbs and articulations. Major is classified based on tissue separation:[11]

Simplex – above stratum basale

Junctional – within dermal-epidermal junction

Dystrophies – beneath entire dermal epidermal junction.

Sever cases reveal scaring, microstomia, obliteration of oral vestibule and ankyloglossia.

Erythema Multiforme

It is typical, self-limiting and recurring mucocutaneous reaction characterized by the target or iris lesions of skin and mucous membrane.

Erythema multiforme is an immune mediated disease with hypersensitive reaction to infection and medications. Herpes simplex virus, fungal infections and drugs like barbiturates nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drug s pencillins, etc., are considered to be the etiology.[12] It presents as mild self-limiting with mild oral involvement to progressive fulminating variant Steven Johnson syndrome.

Oral lesions are seen in 70% of patients with erythema multiforme as vesicles or bullae which rupture and leave a white or yellow exudate. Painful bloody crusting ulcerations are viewed on the lips.

Histopathological section shows intercellular edema of superficial connective tissue with subepidermal vesicle. Liquefaction degeneration with superficial epithelium or corneal areas. Basal cell degeneration is seen.

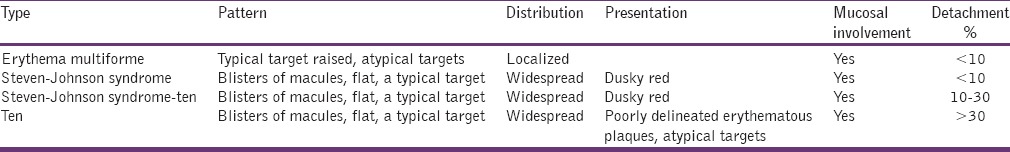

Diagnosis is based, clinically Steven Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN) there is raised in blood sedimentation rate, transient decline in CD4+ T lymphocytes may be noticed in TEN [Table 2].

Table 2.

Clinical presentation

Lupus Erythematosus

Systemic lupus erythematosus is an autoimmune disease with a wide range of clinical presentation involving all organs and tissues. Etiology includes both genetics and environmental with higher incidence in females. Toll like receptors and Type I interferon signaling pathways play a major role.[13] Environmental factors are ultraviolet light, demethylating drugs and infections or endogenous virus. Hormonal factors include estrogen and prolactin have high incidence in favor.

Criteria

Malar patch

Oral ulcers

Hematological disorders

Photosensitivity

Neurological disorders

Renal disorders.

Discoid Lupus Erythematosus

The chronic dermatological disease leads to scarring. It is a collagen vascular lesion. Oral lesions occur on labial mucosa, vermilion borders and buccal mucosa. Clinically present as white popular central erythema, a border forming radiating white striae and peripheral telengactasia.

Histopathological shows hyperortho/parakeratosis, liquefaction degeneration of basal layer infiltration of lymphocytes.

Scleroderma

Microstomia

Xerostomia

Telengectasia

Discordlupuserythematosus

Fungal infection

Gingivitis

Ulcers.

It is a disease of the multisystem involving the immune system, blood vessels and connective tissue. The diagnosis can be made based on clinical symptoms, barium swallow, and endoscopy.[14]

Bechets Syndrome

It is characterized by chronic, relapsing multisystemic inflammatory disorder characterized by oral aphthous ulcers, genital ulcer, skin lesions, ocular lesions.[15] Etiopathogenesis include genetic and environmental. Diagnosis can be made according to clinical criteria proposed by international study group for Behcet's disease.[16] Recurrent oral ulcers which are difficult to distinguish between recurrent aphthous stomatitis and recurrent oral ulcers in Bechet syndrome.

Conclusion

Oral lesions contribute to patients morbidity affecting the psychological and economic functioning of the individual and community. These lesions can cause pain, discomfort and other symptoms and in most cases seek treatment.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Kharodawala M. Grand Rounds Presentation The University of Texas Medical Branch Department of Otolaryngology; April 26. 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jonsson U. United nations: Published by UNICEF; 2003. Human Rights Approach to Development Programming. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Robert E, Marx, Diane, Stern Oral and maxillofacial pathology: A rationale for diagnosis and treatment Vol 1. ed. Quintessence Books: United nations. 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vojdani A, Bryan O, Kellerman G. The immunology of immediate and delayed hypersensitivity reaction to gluten. Eur J Inflamm. 2008;6:1–10. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Regezi JA, Sciubba JJ, Jordan RCK, Kazmierowski JA, Krik D, Sapp JP, et al. 2nd ed. St. Louis (MI): Mosby; 2004. Contemporary Oral and Maxillofacial Pathology. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Regezi JA, Sciubba JJ, Jordan RCK. 3rd ed. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 1999. Oral Pathology: Clinical Pathologic Correlations. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Carrozzo M, Gandolfo S. The management of oral lichen planus. Oral Dis. 1999;5:196–205. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-0825.1999.tb00301.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shamim T, Varghese VI, Shameena PM, Sudha S. Pemphigus vulgaris in oral cavity: Clinical analysis of 71 cases. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2008;13:E622–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mihai S, Sitaru C. Immunopathology and molecular diagnosis of autoimmune bullous diseases. J Cell Mol Med. 2007;11:462–81. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2007.00033.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.O’Regan E, Bane A, Flint S, Timon C, Toner M. Linear IgA disease presenting as desquamative gingivitis: A pattern poorly recognized in medicine. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2004;130:469–72. doi: 10.1001/archotol.130.4.469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wright JT, Fine JD, Johnson L. Hereditary epidermolysis bullosa: Oral manifestations and dental management. Pediatr Dent. 1993;15:242–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kazmierowski JA, Wuepper KD. Erythema Multiforme: Clinical Spectrum and Immunopathogenesis. Springer Semin: Immunopathology. 1981;4:45–53. doi: 10.1007/BF01891884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bertsias G, Cervera R, Bournpass DT. Systemic Lupus Erythematosus: Pathogenesis and Clinical Features. J Clin Exp Dermatol Res. 2012;20:476–505. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jaovisidha K, Csuka ME, Almagro UA, Soergel KH. Severe gastrointestinal involvement in systemic sclerosis: Report of five cases and review of the literature. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2005;34:689–702. doi: 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2004.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kovacova E, Salmas J, Stenova E, Bedeova J, Duris I. Behcet's syndrome. Bratisl Lek Listy. 2005;106:386–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Neurol L. Criteria for diagnosis of Behçet's disease. International Study Group for Behçt's Disease Lancet. 1990;335:1078–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]