Abstract

The zygomaticomaxillary complex (ZMC) plays a key role in the structure, function, and esthetic appearance of the facial skeleton. They can account for approximately 40% of mid-face fractures. They are the second most common facial bone fracture after nasal bone injuries. The fracture complex results from a direct blow to the malar eminence and results in three distinct fracture components that disrupt the anchoring of the zygoma. In addition, the fracture components may result in impingement of the temporalis muscle, trismus (difficulty with mastication) and may compromise the infraorbital foramen/nerve resulting in hypesthesia within its sensory distribution. A 4-year retrospective review of all patients treated with ZMC fractures at oral and maxillofacial surgery department, sree balaji dental college and hospital was performed. Computed tomography scans were reviewed. Demographics, treatment protocols, outcomes, complications, reoperations, and length of follow-up were identified. A total of 245 patients was identified by the Current Procedural Terminology codes for ZMC fractures. Closed or open reduction methods were performed with the goal of treatment being preservation of normal facial structure, sensory function, globe position, and mastication functionality. Unacceptably poor surgical outcomes are uncommon. Significant facial asymmetry requiring surgical revision occurs in 3-4% of patients. Postoperative infection rates are extremely low, and these infections nearly always resolve with oral antibiotics. In general, the long-term prognosis after repair of ZMC fractures is very good.

KEY WORDS: Antibiotics, computed tomography scans, fracture, open reduction, surgical procedures, zygomaticomaxillary complex

The zygomaticomaxillary complex (ZMC) plays a key role in the structure, function, and esthetic appearance of the facial skeleton.[1] A ZMC fracture is also known as a tripod, tetrapod or quadripod fracture, trimalar fracture or malar fracture. Fractures of the zygomatic complex are among the most frequent in maxillofacial trauma.[2,3] The etiology of zygomatic complex fractures includes road traffic accidents, assaults, falls, sports, and missile injuries.[4,5,6] Earlier studies listed traffic accidents as the major etiological factor of maxillofacial injuries.[7,8] The relative contribution of these factors varies from region to region.[5,6] The ZMC fractures present a challenging diagnostic and reconstructive task to the surgeon.[9] However, surgical intervention is not usually taken up unless a functional or esthetic impairment in the form of reduced mouth opening and depression of the cheek prominence is encountered. Although many surgical treatment modalities have been mentioned so far, every technique may have its own limitations.

Fractures of the zygomatic complex appear commoner in young adult males.[6,10,11] Common clinical features of zygomatic complex fractures include diplopia, enophthalmos, subconjunctival ecchymosis, flattening of the cheek, gagging of the occlusion, and sensory disturbances.[3,12,13,14] Diagnosis of zygomatic complex fractures is usually clinical, with radiographic confirmation.[15] Although isolated zygomatic complex fractures occur, several studies have shown that fractures of the zygomatic complex are often associated with other maxillofacial injuries.[2,16]

Patients and Methods

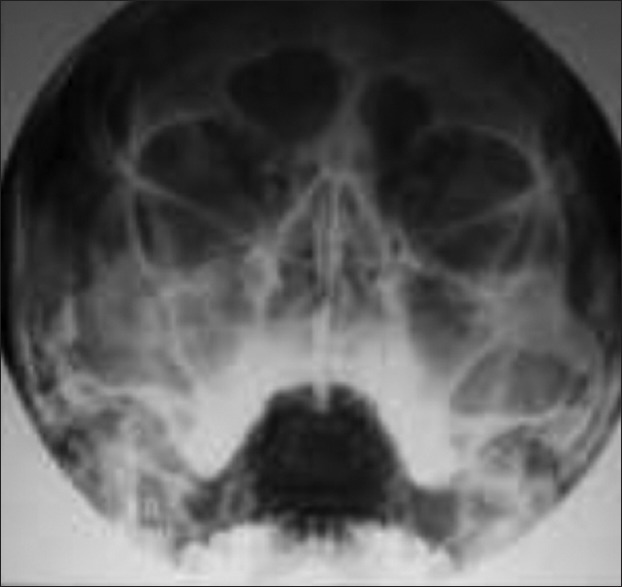

Over a 4-year period (2011–2014), 245 patients with fractures of the zygomatic complex were retrospectively studied at Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery Department, Sree Balaji Dental College and Hospital. These patients were selected from a pool of 960 patients who sustained maxillofacial fracture during the period under review.[17] Data documented were the patient's age, sex, and etiology of the fracture. Other data recorded were the site of fracture (zygomatic bone or arch), associated maxillofacial injuries, clinical presentation, radiographic findings, treatment, duration of follow-up, and complications [Figure 1]

Figure 1.

Preoperative X-ray

Results

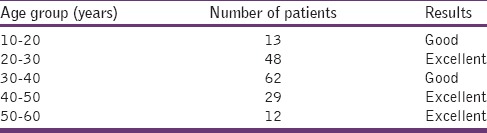

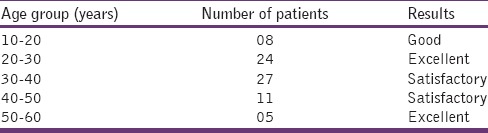

The age group of the patients varied from 18 to 60 years. The highest incidence of fracture was seen between the age group of 20 and 40 years. Many studies have shown that young adult males were commonly affected.[6,10,8] Two hundred and thirteen (86%) patients were male and 32 (10%) patients were female [Table 1]. Ninety-eight (40%) patients had left side and 147 (60%) had right sided fractures. The role of road traffic accidents as an etiologic factor in zygomatic complex fractures has been identified by some studies.[2,5,15,18,19] [Table 2]. Two hundred and eighteen (89%) patients sustained fractures of the zygomatic bone, 22 (9%) had fractures of the zygomatic arch, and 5 (2%) patients had fractures of both the arch and the zygomatic bone. All patients were treated by open reduction and rigid internal fixation using titanium mini plates and screws. 28 (70%) cases were managed by two-point fixation and 8 (20%) by three-point fixation.[20] Isolated arch fracture stabilization was done in 4 (10%) cases. Antibiotic regimen of intravenous use of injection ampicillin 500 mg every 6 h, injection amikacin 500 mg every 12 h, injection metronidazole 500 mg every 8 h for total 3–5 days was followed as a protocol in our center.[21] Patients were reviewed with check radiograph to assess fracture stabilization, approximation, and immobilization. Function, esthetics, and neurological assessments were done in immediate postoperative phase and during periodic review. Ocular functions such as eye movements, presence/absence of diplopia were assessed postoperatively.[22,23]

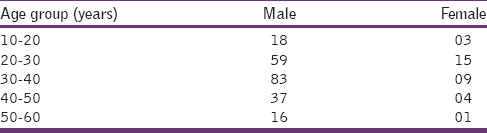

Table 1.

Age and gender distribution of patients

Table 2.

Etiology of zygomatic fractures

Discussion

This study recorded that more males than females (ratio 4:1) sustained zygomatic complex fractures. This is consistent with other reports. 22–37 Males in the 20–40 year age group were most often involved, and road traffic accidents were the leading etiologic factor. Many studies have shown that young adult males were commonly affected.[6,10,18] The role of road traffic accidents as an etiologic factor in zygomatic complex fractures has been identified by some studies.[3,5,15,18,19] The key to management of facial trauma is to operate the cases as soon as clinical conditions permits with a special emphasis on function and esthetics.[24]

The present study recorded more fractures of the zygomatic bone (89%) than those of the arch (9%) or combined zygomatic bone and arch (2%). Isolated fractures of the arch are uncommon.[5] This was probably because of the predominant role of road traffic accidents, in which most impacts to the face were most likely frontal. Arch fractures are more likely to involve some form of lateral impact and were more often encountered in cases of falls, assaults, and sport in this study.

As a result of the intimate association of the zygomatic complex with the rest of the facial skeleton, associated maxillofacial fractures are common. The findings from this study are similar to the associated facial bone fractures seen in patients with fractures of the zygomatic complex reported by other studies. These studies[5,25,26] showed that mandibular fractures were most often associated with zygomatic complex fractures.

Although several signs and symptoms accompany zygomatic complex fractures,[1,5,13,26] not all require active treatment. Circumorbital ecchymosis and subconjunctival ecchymosis were most frequently encountered in this study but were usually self-limiting. Banks and Brown[6] have summarized the indications for treatment as follows: to restore the normal contour of the face both for cosmetic reasons and to establish skeletal protection for the globe of the eye, to correct diplopia and to remove any interference with the range of movement of the mandible.

Flattening of the cheek was encountered among 43% of patients in the study. This is usually seen in tripod fractures that are most often displaced in wards to a greater or lesser extent.[5] Diplopia was observed in 7.6% of patients in this study. al-Qurainy et al.[13] reported diplopia in 17.4% of patients with mid-face fractures and found that zygomatic fractures were a principal risk factor in the development of diplopia.[13] Limitation of mandibular movement occurred in 59% of patients and is usually a result of the fractured zygomatic complex impinging on the coronoid process of the mandible.[5] Based on recent reports, the most significant types of chronic residual sequelae of zygomatic bone fracture are deformities resulting from mal reduction of the zygomatic prominence, enophthalmos, cheek anesthesia or dysesthesia, and trismus.[27]

Radiographic examination in fractures of the zygomatic complex appears somewhat unresolved. In the 1994 survey[28] of British oral and maxillofacial surgeons, 93.3% of respondents use two or more radiographs for diagnostic purposes. Only 6.7% of surgeons would rely on a single radiograph for diagnosis.[28] This is similar to the findings in this study wherein 79% of the cases two or more radiographs were requested for diagnosis. In only 21% of the cases was one radiograph requested. Earlier, Ogden et al.[29] had proposed that in some fractures of the zygomatic complex, clinical criteria alone were sufficient for postoperative assessment. Pogrel et al.[30] evaluated the efficacy of a single radiograph to screen for mid-face fractures and concluded that a single 30° occipitomental radiograph (augmented with computed tomography (CT) scans when indicated) can identify all mid-face fractures requiring treatment. In this study, 93% of patients had postoperative radiographs taken [Figures 2–4]. The most frequent radiologic findings were fractures at the zygomaticomaxillary and zygomaticofrontal sutures (48%). [Figure 3] The suture lines of the zygomatic complex are the weak points of the bone, as it is unusual for the zygomatic bone itself to be fractured.[6] The use three-dimensional CT before surgery can help in determining the severity of zygoma complex fractures and the displacement of bone segments in the preoperative period with-out the need for an open procedure.[31]

Figure 2.

Postoperative X-ray one-point fixation

Figure 4.

Postoperative X-ray two-point fixation

Figure 3.

Preoperative X-ray

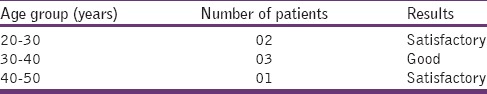

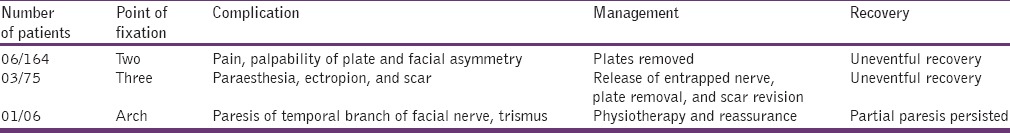

The transoral approach was the most common method of reduction.[14] This is consistent with other reports.[1,10,13,14,15,17,18,19,22,26,28,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39] McLoughlin et al.[28] found that the use of the bone plating was not significantly greater than the use of transosseous wiring among British oral and maxillofacial surgeons. However, Tadj and Kimble,[40] in a study of 263 cases of fractured zygomatic complex, found that bone plating was the most frequently employed fixation. Two-point fixation methods were preferred to achieve stability against rotation with best esthetic outcome as the scars were well hidden intraorally and in the eyebrows.[41] This approach provided best result with minimal complications such as pain, palpability of implants, and mild facial asymmetry in one case [Tables 3–5]. However, opinions vary, and different combinations have been documented in the literature.[42] Few cases were managed by more than two-point fixation, but no extra benefits were achieved from these approaches on reduction and stabilization point of view vis-à-vis two-point fixation, and one patient in this group developed complications [Table 6]. The study revealed that the three-point fixation using miniplates conferred the greatest stability. However, three-point wire fixation was only slightly less stable.[8] Mixing wires with miniplates reduced the stability in proportion to the number of wires used. Minimal increases in stability were added using three-point miniplate fixation when compared to two-point miniplate fixation, regardless of the application site. The authors concluded that a stable fixation can be achieved with a miniplate on the frontozygomatic suture line and a second buttress. Acceptable stability can be achieved with single-point miniplate fixation at the frontozygomatic suture line or the infraorbital rim.[33] These results do not take into account variables like fracture comminution rotatory forces of the masseter muscle or the type of skin incision necessary to apply the fixation.

Table 3.

Treatment details - two-point fixation (164 patients)

Table 5.

Treatment details-isolated arch fixation (06 patients)

Table 6.

Complications

Table 4.

Treatment details - three-point fixation (75 patients)

Most (76%) patients in this study came for follow-up on regular intervals. This study found postoperative complications among 6.7% of the patients. Covington et al.[36] reported a complication rate of 1.5%, while Tadj and Kimble[40] reported a rate of 20.7%. Blindness is an extremely morbid event and was encountered in 3.0% of patients. In all cases, it was preceded by decreasing visual acuity. In this study, ophthalmic consultation was usually sought for patients with impaired ocular functions. The role of the ophthalmologist in the perioperative assessment of patients with zygomatic complex has been documented.[37,42]

Zachariades et al.,[38] in an analysis of 5,936 patients with facial trauma, found that vision were lost in 18 patients. Zygomatic complex fractures accounted for 0.45% of cases. Apart from direct injury to the globe of the eye,[38] the mechanism for the development of blindness in zygomatic complex fractures is thought to be due to hemorrhage within the muscle cone and ultimately spasm or occlusion of the short posterior ciliary arteries, causing ischemia of a critical zone of the optic nerve.[9] Other complications were persistent flattening of the cheek (3.0%) and persistent enophthalmos (0.7%), and these were as a result of inadequate surgical management.

Postoperative facial asymmetry occurs in 20–40% of patients.[43] Although facial fracture reductions can be strenuous and time consuming, failure to obtain adequate exposure and precise reduction at the time of the initial repair often results in cosmetic deformities. Most postoperative irregularities require no surgical intervention; however, major asymmetry occurs in 3–4% of patients. Osteotomies and bone grafting may be required.[34,43]

Zygomaticomaxillary complex fractures often traverse the infraorbital foramen and result in infraorbital nerve injury. Preoperative evaluation and documentation of infraorbital nerve function is strongly recommended. Patients should be counseled that the sublabial incision itself will result in some transient postoperative anesthesia of the upper gingiva. The incidence of persistent sensory dysfunction ranges from 22% to 65% for open reductions and 9–40% for closed reductions.[34,35] In one large series, iatrogenic injuries were noted in 11% of open reductions.[35] Excessive traction or surgical manipulation of the infraorbital nerve during exposure and fracture reduction will also increase the risk of postoperative paresthesias. While these symptoms can be distressing to the patient, observation and reassurance are the most appropriate treatments. Attempts at surgical decompression or ablation are highly unpredictable.[44]

Coronal incisions will also result in postoperative paresthesias/anesthesia of the supraorbital and supratrochlear dermatomes distal to the incision. Aggressive manipulation of the nerve at the foramina can exacerbate these symptoms. Resolution of the paresthesias is slow and can be extremely frustrating to some patients. All patients should be warned regarding the postoperative sequelae and counseled that resolution of the symptoms (which may be partial or complete) cannot be expected for 3–12 months after the surgery.

Postoperative sinusitis was related directly to the severity of injury. Patients rarely complained of pain over titanium plates with cold exposure. Plate exposure was evidenced in few patients. The absence of infection, intraoral exposure of plates or wires was monitored conservatively. These wounds often granulate with appropriate oral hygiene. Persistent exposure for longer than 3 months, evidence of loose plates, or gross infection was indications for plate removal.

Conclusion

Facial bones, especially of the middle third of the face, are composed of a network of fragile bones held together across sutures which give way in case of force to a lesser extent than other parts of the body. The key to management of facial trauma is to operate the cases as soon as clinical conditions permit with a special emphasis on function and esthetics. This study has shown that closed reduction and internal fixation of ZMC fractures provide adequate reduction of these injuries. This surgical technique results in good bony alignment and esthetics, as measured by postoperative CT scans and patient questionnaires. Significant facial asymmetry requiring surgical revision occurs in 3–4% of patients. Postoperative infection rates are extremely low, and these infections nearly always resolve with oral antibiotics. In general, the long-term prognosis after repair of ZMC fractures is very good.

This study has also shown that road traffic accidents are responsible for most zygomatic complex fractures in our environment. With the introduction of compulsory use of seatbelts in developed nations, there is a significant reduction of facial injuries.[45,46] In India, as per Motor Vehicle Act use of seatbelts and helmets is compulsory, but the compliance is poor. It is imperative to educate people regarding the use of headgear (crash helmet) and seatbelts while traveling in motorized transport which will go a long way in preventing injuries to the facial region.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Jansma J, Bos RR, Vissink A. Zygomatic fractures. Ned Tijdschr Tandheelkd. 1997;104:436–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fasola AO, Obiechina AE, Arotiba JT. An audit of midfacial fractures in Ibadan, Nigeria. Afr J Med Med Sci. 2001;30:183–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hollier LH, Thornton J, Pazmino P, Stal S. The management of orbitozygomatic fractures. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2003;111:2386–92. doi: 10.1097/01.PRS.0000061010.42215.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Afzelius LE, Rosén C. Facial fractures. A review of 368 cases. Int J Oral Surg. 1980;9:25–32. doi: 10.1016/s0300-9785(80)80003-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Banks P, Brown A. 1st ed. Oxford: Wright; 2001. Fractures of the Facial Skeleton; pp. 40–155. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Motamedi MH. An assessment of maxillofacial fractures: a 5-year study of 237 patients. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2003;61:61–4. doi: 10.1053/joms.2003.50049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bogusiak K, Arkuszewski P. Characteristics and epidemiology of zygomaticomaxillary complex fractures. J Craniofac Surg. 2010;21:1018–23. doi: 10.1097/scs.0b013e3181e62e47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Salinas JB, Vira D, Hu D, Elashoff D, Abemayor E, St John M. Steimann pin repair of zygomatic complex fractures. Int J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2013;2:74–8. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ord RA, Awty MD, Pour S. Bilateral retrobulbar haemorrhage: a short case report. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1986;24:1–6. doi: 10.1016/0266-4356(86)90031-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tanaka N, Tomitsuka K, Shionoya K, Andou H, Kimijima Y, Tashiro T, et al. Aetiology of maxillofacial fracture. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1994;32:19–23. doi: 10.1016/0266-4356(94)90166-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fasola AO, Nyako EA, Obiechina AE, Arotiba JT. Trends in the characteristics of maxillofacial fractures in Nigeria. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2003;61:1140–3. doi: 10.1016/s0278-2391(03)00671-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Souyris F, Klersy F, Jammet P, Payrot C. Malar bone fractures and their sequelae. A statistical study of 1-393 cases covering a period of 20 years. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 1989;17:64–8. doi: 10.1016/s1010-5182(89)80047-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.al-Qurainy IA, Stassen LF, Dutton GN, Moos KF, el-Attar A. Diplopia following midfacial fractures. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1991;29:302–7. doi: 10.1016/0266-4356(91)90115-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.al-Qurainy IA, Stassen LF, Dutton GN, Moos KF, el-Attar A. The characteristics of midfacial fractures and the association with ocular injury: a prospective study. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1991;29:291–301. doi: 10.1016/0266-4356(91)90114-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ait Benhamou C, Kadiri F, Laraqui N, Benghalem A, Touhami M, Chekkoury A, et al. Zygomatic-orbito-malar fractures. Apropos of 85 cases. Rev Laryngol Otol Rhinol (Bord) 1996;117:15–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Linn EW, Vrijhoef MM, de Wijn JR, Coops RP, Cliteur BF, Meerloo R. Facial injuries sustained during sports and games. J Maxillofac Surg. 1986;14:83–8. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0503(86)80266-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.De Gioanni PP, Mazzeo R, Servadio F. Sports activities and maxillofacial injuries. Current epidemiologic and clinical aspects relating to a series of 379 cases (1982-1998) Minerva Stomatol. 2000;49:21–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bataineh AB. Etiology and incidence of maxillofacial fractures in the north of Jordan. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 1998;86:31–5. doi: 10.1016/s1079-2104(98)90146-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Muraoka M, Nakai Y, Nakagawa K, Yoshioka N, Nakaki Y, Yabe T, et al. Fifteen-year statistics and observation of facial bone fracture. Osaka City Med J. 1995;41:49–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kim ST, Go DH, Jung JH, Cha HE, Woo JH, Kang IG. Comparison of 1-point fixation with 2-point fixation in treating tripod fractures of the zygoma. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2011;69:2848–52. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2011.02.073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hasse PN, Gealh WC, Pereira CC, Coradazzi LF, Magro Filho O, Rangel Garcia I., Jr Clinical and radiographic evaluation of surgical treatment of zygomatic fractures using 1.5 mm miniplates system. Open J Stomatol. 2011;1:172–8. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Longaker MT, Kawamoto HK., Jr Evolving thoughts on correcting posttraumatic enophthalmos. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1998;101:899–906. doi: 10.1097/00006534-199804040-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Barry C, Coyle M, Idrees Z, Dwyer MH, Kearns G. Ocular findings in patients with orbitozygomatic complex fractures: a retrospective study. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2008;66:888–92. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2008.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chattopadhyay PK. Management of zygomatic complex fracture in armed forces. Med J Armed Forces India. 2009;65:128–30. doi: 10.1016/S0377-1237(09)80124-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ellis E, 3rd, el-Attar A, Moos KF. An analysis of 2,067 cases of zygomatico-orbital fracture. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1985;43:417–28. doi: 10.1016/s0278-2391(85)80049-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nam IW. Clinical studies on treatment of fractures of the zygomatic bone. Taehan Chikkwa Uisa Hyophoe Chi. 1990;28:563–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kurita M, Okazaki M, Ozaki M, Tanaka Y, Tsuji N, Takushima A, et al. Patient satisfaction after open reduction and internal fixation of zygomatic bone fractures. J Craniofac Surg. 2010;21:45–9. doi: 10.1097/SCS.0b013e3181c36304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McLoughlin P, Gilhooly M, Wood G. The management of zygomatic complex fractures – results of a survey. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1994;32:284–8. doi: 10.1016/0266-4356(94)90047-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ogden GR, Cowpe JG, Adi M. Are post-operative radiographs necessary in the management of simple fractures of the zygomatic complex? Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1988;26:292–6. doi: 10.1016/0266-4356(88)90046-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pogrel MA, Podlesh SW, Goldman KE. Efficacy of a single occipitomental radiograph to screen for midfacial fractures. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2000;58:24–6. doi: 10.1016/s0278-2391(00)80009-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Park BY, Song SY, Yun IS, Lee DW, Rah DK, Lee WJ. First percutaneous reduction and next external suspension with Steinmann pin and Kirschner wire of isolated zygomatic fractures. J Craniofac Surg. 2010;21:1060–5. doi: 10.1097/SCS.0b013e3181e62cb2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chae YP, Kim SK. Clinical study on surgical treatment of zygoma fractures. Taehan Chikkwa Uisa Hyophoe Chi. 1989;27:949–57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Davidson J, Nickerson D, Nickerson B. Zygomatic fractures: comparison of methods of internal fixation. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1990;86:25–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zingg M, Chowdhury K, Lädrach K, Vuillemin T, Sutter F, Raveh J. Treatment of 813 zygoma-lateral orbital complex fractures. New aspects. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1991;117:611–20. doi: 10.1001/archotol.1991.01870180047010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zingg M, Laedrach K, Chen J, Chowdhury K, Vuillemin T, Sutter F, et al. Classification and treatment of zygomatic fractures: a review of 1,025 cases. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1992;50:778–90. doi: 10.1016/0278-2391(92)90266-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Covington DS, Wainwright DJ, Teichgraeber JF, Parks DH. Changing patterns in the epidemiology and treatment of zygoma fractures: 10-year review. J Trauma. 1994;37:243–8. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199408000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jayamanne DG, Gillie RF. Do patients with facial trauma to the orbito-zygomatic region also sustain significant ocular injuries? J R Coll Surg Edinb. 1996;41:200–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zachariades N, Papavassiliou D, Christopoulos P. Blindness after facial trauma. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 1996;81:34–7. doi: 10.1016/s1079-2104(96)80144-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ashar A, Kovacs A, Khan S, Hakim J. Blindness associated with midfacial fractures. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1998;56:1146–50. doi: 10.1016/s0278-2391(98)90757-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tadj A, Kimble FW. Fractured zygomas. ANZ J Surg. 2003;73:49–54. doi: 10.1046/j.1445-2197.2003.02595.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Karlan MS, Cassisi NJ. Fractures of the zygoma. A geometric, biomechanical, and surgical analysis. Arch Otolaryngol. 1979;105:320–7. doi: 10.1001/archotol.1979.00790180018004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yonehara Y, Hirabayashi S, Tachi M, Ishii H. Treatment of zygomatic fractures without inferior orbital rim fixation. J Craniofac Surg. 2005;16:481–5. doi: 10.1097/01.scs.0000157308.39420.74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Perino KE, Zide MF, Kinnebrew MC. Late treatment of malunited malar fractures. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1984;42:20–34. doi: 10.1016/0278-2391(84)90391-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Donald PJ. Zygomatic fractures. In: English GM, editor. Otolaryngology: A Text Book. 1st ed. Hagerstown, Md: Medical Dept, Harper and Row; 1976. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Steele RJ, Little K. Effect of seat-belt legislation. Lancet. 1983;2:341. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(83)90318-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chuong R, Kaban LB. Fractures of the zygomatic complex. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1986;44:283–8. doi: 10.1016/0278-2391(86)90079-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]