Abstract

To identify the role of dietary habits (type of diet, skipping meals, snacking in-between meals and frequency of visits to fast food restaurants) in caries occurrence and severity. To explore the correlation between frequency of intake of selected foods and dental caries. A cross-sectional study was carried out on adolescent children (n = 916) of age 13-19, following a two-stage random sampling technique. Data were collected using a pretested questionnaire. Questionnaire included demographic details, dietary habits of children and food frequency table that listed selected food items. The dependent variable-dental caries was measured using the decayed, missing, filled teeth (DMFT) index. The prevalence of dental caries in this study population was 36.7% (95% confidence interval: 33.58-39.82). The mean DMFT was 1.01 (±1.74). No statistically significant difference found between caries occurrence and type of diet (P = 0.07), skipping meals (P = 0.86), frequency of eating in fast food stalls (0.86) and snacking in between meals (0.08). Mean DMFT values were higher among nonvegetarians and among children who had the habit of snacking in between meals. Frequency of intake of selected food items showed that mean frequency intake of carbonated drinks and confectionery was higher among children who presented with caries when compared to caries-free children (P = 0.000). Significant correlation found between mean DMFT and mean frequency intake of carbonated drinks and confectionery. Odds ratios were calculated for the same for frequency ≥4 times/day for confectionery and ≥4/week for carbonated drinks and results discussed. Frequent intake of carbonated drinks and confectionery is harmful to oral health that eventually reflects on general health. Educating the adolescent children on healthy dietary habits should be put in the forefront.

KEY WORDS: Carbonated drinks, confectionery, dental caries, dietary habits

Diet plays an important role in the nutritional status and henceforth the development of an individual. When diet and oral health is considered, Moynihan states that, “Good diet is essential for the development and maintenance of healthy teeth, but healthy teeth are important in enabling the consumption of a varied and health diet throughout life cycle,” thus emphasizing the two-way relationship between diet and oral health.[1] Dental caries is a multifactorial disease with diet being one of the contributing factors is well documented by numerous studies.

Children and adolescents form the backbone of future generation and many serious diseases in adulthood have their roots in adolescence, for example, dietary habits and tobacco usage.[2] Unhealthy lifestyle factors like skipping meals and food choice leading to a poorer nutrient intake are common among this vulnerable adolescent group.[3] Children and adolescents are giving preferences for sweetened foods,[4] and soft drinks,[5] that are rich in carbohydrate and thus are at risk for caries development. With the known culture difference, where an Indian diet is different from a western diet and with not many studies addressing this issue there arises the need to explore this concept of diet, and in recent decades with the western culture influences in the urban sector especially in relation to diet, there goes the need to study the Indian urban scenario.

Thus, this study was undertaken in the urban metropolitan city of Chennai with the following objectives: (1) To identify the role of dietary habits (type of diet, skipping meals, snacking in-between meals and frequency of visits to fast food restaurants) in caries occurrence and severity. (2) To determine the correlation between frequency of intake of selected food items and dental caries (occurrence and severity).

Methodology

A cross-sectional study was done on adolescent school children of age 13–19. A pilot study was carried out on a sample of adolescent school children of similar age group (n = 114). The pilot study helped in identifying difficulties in the data collection procedure and also helped in testing the questionnaire. The pilot study pointed a prevalence of dental caries as 42.1%. So, the sample size required under simple random sampling method was 863 (8% of prevalence was the variance allowed with α at 5% level of significance). Adding 5% dropouts the total number of children required for the study was 906.

A two-stage random sampling technique was followed wherein the first stage included random selection of schools from the list of schools in Chennai. A list of higher secondary schools in Chennai that included 448 schools was prepared from the internet database.[6] By means of random sampling eight, schools were selected from the 448 schools. Second stage included random selection of children in the specified age group of 13–19, from the selected schools by proportion to the population sample (PPS) selection technique. With inclusion criteria of age 13–19 for this present study, children of class 9th–12th standard were the target population in each of the eight schools. List of students in each school for the above-stated classes were provided by the school head. After exclusion criteria, a total of 3806 children from all eight schools formed the sampling frame. Using the PPS technique (proportion to population) the number of children to be included as study samples from each school was calculated. These study children were randomly selected from the list of total students studying in that particular school. Thus, a total of 916 (extra 10 children were sampled) adolescent schoolchildren of age 13–19 formed our study sample.

Permission was sought to the Principals in charge of the schools, to carry out the study. Information was provided regarding the nature and the need of the study. The results discussed in this article are part of the study, “Effect of nutrition on dental caries” and was cleared by the Institutional Ethical Committee.

Data collection

Questions on frequency of visit to a fast food restaurant, habit of skipping meals, and habit of snacking in between meals, type of diet (vegetarian or nonvegetarian) was incorporated into the questionnaire, considering them as possible risk indicators for dental caries. A food frequency questionnaire was incorporated with the help of a nutritionist. The frequency of intake of the following food items was taken up for the study: Sugar (number of spoons/day), milk (no of cups/day), confectionery (sweets and chocolates/day), fruits and vegetables (in a week), nuts and pulses (frequency/week), nonvegetarian foods (frequency/week), junk foods (frequency/week), carbonated drinks (frequency/week), fresh fruit juices (frequency/week).

Food items were tabulated, and the children were instructed to write down the number of times, on an average, they consume a particular item in a day or week. If they do not consume a particular item they were instructed to mark as “0”, or if in case they consume any particular item occasionally (>15 days) they would score it as “occasionally”. Oral examination included screening the children for decayed, missing, filled teeth index (DMFT) using the WHO guidelines.[7]

Data were analyzed using the IBM, SPSS(version 20.0, Armonk, NY: IBM Corp). Independent samples t-test, Chi-square test, one-way ANOVA, and correlation tests were carried out. P < 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

The prevalence of dental caries in this study population was 36.7% (95% confidence interval: 33.58–39.82). The mean DMFT was 1.01 (±1.74).

Dietary habits and caries occurrence

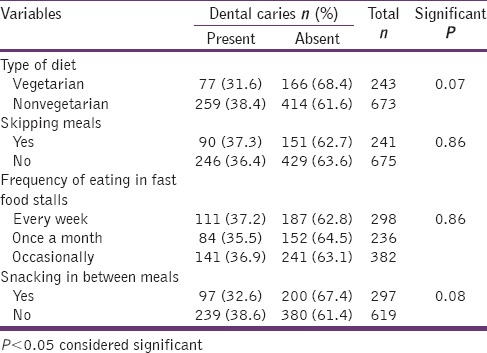

When type of diet was considered it was observed that caries occurrence was found to be higher among nonvegetarians (38.4%) when compared to vegetarians (31.6%). The results showed that there was no statistically significant difference between caries occurrence and type of diet (P = 0.07), skipping meals (P = 0.86), frequency of eating in fast food stalls (P = 0.86) and snacking in between meals (P = 0.08) [Table 1].

Table 1.

Various dietary habits and its relation with caries occurrence

Dietary habits and caries severity

Mean DMFT values were higher among children who are nonvegetarians (1.09) compared to vegetarians (0.80) with a statistical significant different between the two groups (P = 0.015). It was also observed that mean DMFT was higher among children who snacked in between meals (1.04) compared to children who do not (0.96) (P = 0.48). Table 2 reveals that the mean DMFT values do not differ significantly between children who skip meals or not and among children who visit fast food restaurants at different intervals.

Table 2.

Dietary habits and caries severity (mean DMFT)

Food frequency and caries occurrence and severity

It is observed that the mean frequency intake of carbonated drinks was found to be higher among children who presented with caries (3.16) compared to caries-free children (1.79) and there seems to be a statistically significant difference between the two groups with P = 0.000. Similar results are also observed in relation to intake of confectionery that includes sweets and chocolates. The results shown indicates that mean frequency intake of confectionery was significantly higher among children who had caries (3.13) compared to caries free group whose mean frequency was 1.44 (P = 0.000). When comparing other food groups, the mean frequency intake was almost similar among children who were caries free or who presented with caries with significant P > 0.05 [Table 3]. It is concluded that frequent intake of confectionery and carbonated drinks is associated with caries occurrence.

Table 3.

Caries occurrence (present or absent) in relation to mean frequency intake of different food

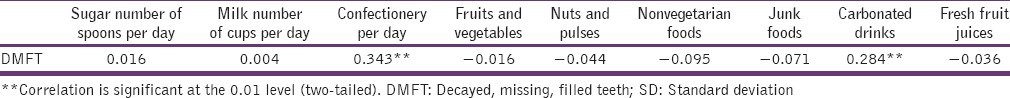

Correlation between mean DMFT and mean frequency intake of food items was analyzed, and the results are tabulated in Table 4. It shows that DMFT is significantly correlated only with confectionery and carbonated drinks and not with items like sugar, milk, fruits and vegetables, nonvegetarian foods, junk food, or fresh fruit juices.

Table 4.

Correlation between mean DMFT and mean frequency intake of food items

Estimating decayed, missing, filled teeth using frequency of intake of confectionery and carbonated drinks

Research question

Is it possible to assess DMFT, given the frequency of intake of confectionery and carbonated drinks. Multiple regression analysis is used for this purpose, and the regression equation is given by:

Equation: DMFT = 0.208 + 0.213 × confectionery + 0.209 × carbonated drinks

t - value for constant (significant P value): 1.727 (0.085);

t - value for confectionery (significant P value): 5.682 (0.000);

t - value for carbonated drinks (significant P value): 5.483 (0.000).

R2 value: 0.148 F-value: 49.401 significant: 0.000

For assessing the significance of coefficients, t-test is being used. If the significant value of the t-test is <0.05, the coefficient is said to be significant to assess DMFT. The adequacy of the model is determined using ANOVA. If the significant value of F-test used in ANOVA is <0.05 the model is said to be an adequate model. The efficiency of the model is determined based on R2 value that is also known as coefficient of determination. The high value of R2 indicates higher prediction levels of the dependent variable (DMFT) based on the independent variable (confectionery and carbonated/soft drinks) used in the model.

The result of our model indicates that the model is adequate as the significant value of the F-statistic used in ANOVA is <0.05. When the efficiency is considered, R2 is low, indicating that the model if used for predicting DMFT, will correctly predict to the tune of only 15%.

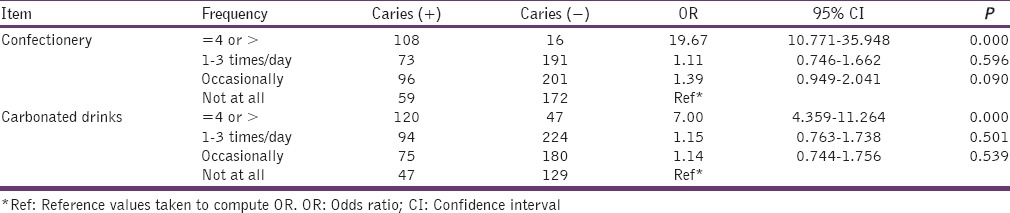

Strength of association between intake of confectionery and carbonated drinks and dental caries

Further calculation of odds ratio (OR) indicated that children who eat confectionery ≥4 times a day are 19.67 times at higher risk of developing caries when compared to children who do not eat confectionery at all (P = 0.000). children who consume carbonated drinks ≥4 times a week were 7 times at higher risk of developing caries when compared to children who do not take carbonated drinks at all (P = 0.000) [Table 5].

Table 5.

Frequency of confectionery intake and carbonated drinks intake versus dental caries

Discussion

Dietary habits

The dietary habits that were studied were consumption of vegetarian and nonvegetarian diet, skipping of meals, snacking in between meals and frequency of eating in fast food stalls. None of the variables studies showed a significant difference in caries occurrence. When caries severity was considered type of diet (vegetarian/nonvegetarian) seemed to be significantly associated with caries severity that is, less among children who are on vegetarian diet. Vegetarian diet contains tannins and phytins (green vegetables) which are cariostatic,[8] but consumption of green vegetables in this age group is questionable. Our study showed that the frequency of intake of fruits and vegetables was same among children who presented with caries or not [Table 3]. Study by Venugopal et al. on Indian children showed that caries prevalence was low in those taking vegetarian type of diet. Frequency of sweet consumption was also shown to be associated with prevalence of dental caries in their study.[9] Almushayt et al. reported that increasing the frequency of eating vegetables will lower the risk of caries (OR = 0.7) than those children who rarely eat vegetables.[10] Study by Yadav et al. among 804 school children of age 5–12 years reported that nonvegetarians had lower prevalence of caries (59.46%) as compared to vegetarians (65.5%) but this was not statistically significant.[11]

In our study it was also observed that children who snacked in between meals had slightly higher mean DMFT (1.04) value when compared to those who do not (0.96) and this was not statistically significant though. Bagramian and Russell had reported no significant relationship between the consumption of sucrose containing between-meal snacks and caries experience.[12] But in this decade with snacking in between meals predominantly containing unhealthy junk food with high carbohydrate content, studies have found a positive correlation between snacking in between meals and caries occurrence. For example, Marshall et al. in his study on the role of meal, snack and daily total food and beverage exposures on caries experience in young children found that higher exposure to sugar at snacks increased caries risk.[13]

Our study did not investigate the intricacies of what types of snacks were eaten in between meals (whether it contained high carbohydrate content). But this present study has made an observation that children who were in the habit of snacking in between meals had higher DMFT values. This finding would serve as an important input to oral health education content on advising or educating the children about avoiding in-between unhealthy snacking behavior. Most children tend to eat unhealthy snacks in-between meals that are usually high in carbohydrate and fat like chips, chocolates, sweets, burgers, fried foods and sugared beverages, as Doméjean-Orliaguet et al.,[14] pointed that frequent eating of snack, sugar and cooked starch between meals will increase risk of caries shown by OR of 1.6. American Dental Association has recommended that children and adults must limit eating and drinking between meals and when they must snack, give preference to nutritious foods identified by the US Department of Agriculture Dietary Guidelines.[15] Our study also found that there was no difference in caries occurrence or severity when the children skipped meals or frequented eating in fast food stalls.

Diet and dental caries

When mean frequency intake of different food items was analyzed, it was observed that intake of carbonated drinks and confectionery (sweets and chocolates) had a significant association with caries occurrence and severity. Children consuming sweets and chocolates (confectionery) >4 times a day were almost 20 times more likely to develop caries. The odds of developing caries was 7.00 (OR = 7.00) times higher among children who were in the habit of drinking carbonated drinks frequently (>4 times a week) when compared to those who do not drink carbonated drinks. Almushayt et al. study among preschool children showed that children who drink soda drinks were 10.71 (OR) times at high risk of caries compared to children who do not.[10] Sohn et al. similarly found a strong significant association of carbonated soft drinks with increased caries risk in the primary dentition.[16] Marshall et al. in his longitudinal study also concluded that higher intake of regular soda drinks was significantly associated with increased odds of developing caries.[17]

Conclusion

When food habits are considered, parents should advise the children on the ill effects of frequent consumption of carbonated drinks on their health and also the effect of frequent consumption of confectionery on teeth. Teachers in school also can contribute in educating the children on this. Health education on healthy eating habits can bring about behavior changes among these adolescent children that they would take forward into their adult life.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Moynihan P. The interrelationship between diet and oral health. Proc Nutr Soc. 2005;64:571–80. doi: 10.1079/pns2005431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.WHO. Adolescent Health. Available from: http://www.who.int/topics/adolescent_health/en/

- 3.Sjöberg A, Hallberg L, Höglund D, Hulthén L. Meal pattern, food choice, nutrient intake and lifestyle factors in the Göteborg Adolescence study. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2003;57:1569–78. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1601726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Drewnowski A, Mennella JA, Johnson SL, Bellisle F. Sweetness and food preference. J Nutr. 2012;142:1142S–8. doi: 10.3945/jn.111.149575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shenkin JD, Heller KE, Warren JJ, Marshall TA. Soft drink consumption and caries risk in children and adolescents. Gen Dent. 2003;51:30–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.List of Higher Secondary Schools in Chennai. [Last accessed on 2014 Jan 12]. Available from: http://www.chennai.tn.nic.in/schools/sch-GS.pdf .

- 7.4th ed. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1997. World Health Organization. Oral Health Surveys: Basic Methods. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cole MF, Eastoe JE, Curtis MA, Korts DC, Bowen WH. Effects of pyridoxine, phytate and invert sugar on plaque composition and caries activity in the monkey (Macaca fascicularis) Caries Res. 1980;14:1–15. doi: 10.1159/000260428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Venugopal T, Kulkarni VS, Nerurker RA, Damle SG, Patnekar PN. Epidemiological study of dental caries. Indian J Pediatr. 1998;65:883–9. doi: 10.1007/BF02831355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Almushayt AS, Sharaf AA, Meligy OS, Tallab HY. Dietary and feeding habits in a sample of pre-school children in severe early childhood caries (S-ECC) JKAU Med Sci. 2009;16:13–36. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yadav RK, Das S, Kumar PR. Dental caries and dietary habits in school going children. Indian J Physiol Pharmacol. 2001;45:258–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bagramian RA, Russell AL. Epidemiologic study of dental caries experience and between-meal eating patterns. J Dent Res. 1973;52:342–7. doi: 10.1177/00220345730520022501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Marshall TA, Broffitt B, Eichenberger-Gilmore J, Warren JJ, Cunningham MA, Levy SM. The roles of meal, snack, and daily total food and beverage exposures on caries experience in young children. J Public Health Dent. 2005;65:166–73. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-7325.2005.tb02807.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Doméjean-Orliaguet S, Gansky SA, Featherstone JD. Caries risk assessment in an educational environment. J Dent Educ. 2006;70:1346–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.American Dental Association. Diet and tooth decay. [Last accessed on 2014 Jan 15];J Am Dent Assoc. 2002 133:527. Available from: http://www.ada.org/sections/scienceand research/pdfs/patient_13.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sohn W, Burt BA, Sowers MR. Carbonated soft drinks and dental caries in the primary dentition. J Dent Res. 2006;85:262–6. doi: 10.1177/154405910608500311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Marshall TA, Levy SM, Broffitt B, Warren JJ, Eichenberger-Gilmore JM, Burns TL, et al. Dental caries and beverage consumption in young children. Pediatrics. 2003;112:e184–91. doi: 10.1542/peds.112.3.e184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]