Abstract

Introduction:

Hyperuricemia is common among adults with prehypertension, especially when the microalbuminuria is present. Hyperuricemia precedes the development of hypertension.

Aim:

(1) To find the association of hyperuricemia in new-onset hypertensive patients. (2) To find the association of hyperuricemia in hypertensive patients with regard to gender and risk factors such as smoking and central obesity.

Material and Methods:

A total of 50 adults aged between 20 and 50 years who had mild early hypertension were selected for the study. Fifty controls without hypertension were enrolled and investigated.

Results:

The association between uric acid (UA) and hypertension was analyzed using Student's t-test and statistical difference were assessed using Pearson coefficient. The study showed a significant difference in UA between the hypertensive subjects and the normotensive controls. There was not a significant difference between waist abnormality, smoking and UA in cases. Males have a higher degree of hyperuricemia than females in hypertensive patients.

Conclusion:

Serum UA is strongly associated with blood pressure (BP) in new and recent onset primary hypertension. The remarkable association of UA with BP in adults is consistent with recent animal model data and the hypothesis that the UA might have a pathogenic role in the development of hypertension.

KEY WORDS: Hypertension, smoking, uric acid, waist circumference

Hypertension is an increasing important medical illness. Hypertension markedly increases the risk for myocardial infarction, stroke, congestive heart failure, peripheral vascular disease, and end-stage renal disease. Worldwide prevalence estimates for hypertension may be as much as 1 billion individuals, and approximately 7.1 million deaths/year may be attributable to hypertension.[1] The WHO reports that suboptimal blood pressure (BP) (>115 mm Hg systolic BP) is responsible for 62% of cerebrovascular disease and 49% of ischemic heart disease, with little variation by sex. Approximately, 30% of adults are still unaware of their hypertension, more than 40% of individuals are not on treatment, and two-thirds of hypertensive patients are not being controlled to BP levels less than 140/90 mm Hg.[1] Studies of uric acid (UA) levels and the development of hypertension have generally been consistent and continuous. Hyperuricemia is also common among adults with prehypertension, especially when the microalbuminuria is present.[1] An elevation in serum UA has been associated with an increased risk for the development of hypertension[2,3] and 25–50%of hypertensive individuals are hyperuricemic.[3] Hyperuricemia also confers increased risk for cardiovascular mortality, especially in women.[2] Despite the clinical and epidemiological evidence, many authorities do not consider an elevated UA to be a true cardiovascular risk factor, because patients with hyperuricemia often have other well-established risk factors for cardiovascular disease, such as hypertension, renal disease, obesity, dyslipidemia, and insulin resistance. Several studies have found that an elevated UA level is an independent risk factor for cardiovascular disease after controlling for the contribution of established risk factors by multivariate analyses. The lack of a mechanism by which UA can cause cardiovascular disease, coupled with the inconclusive clinical and epidemiological data, has left the issue unresolved.

Aim

To find the association of hyperuricemia in new-onset onset hypertensive patients

To find the association of hyperuricemia in hypertensive patients with regard to gender and risk factors such as smoking, central obesity and body mass index (BMI)

To find the association of serum UA in hypertensive patients who have metabolic syndrome.

Materials and Methods

100 recently detected hypertensives were enrolled into this study, and the relation of serum UA to BP was examined.

Inclusion criteria

-

Hypertensive patients, whom are of new-onset and recent onset

(<1-year) without any target end organ damage

Age group between 20 and 50 years

Both sexes were included.

Exclusion criteria

Hypertensive patients with target end organ damage

Hypertensive heart disease as evidenced by left ventricular hypertrophy - electrocardiogram-voltage criteria

Diabetes mellitus – Type 1 and type 2 or metabolic syndrome

Patients with chronic kidney disease

Hypertensive patients with known cerebrovascular disease

Hypertensive patients with coronary artery disease – Myocardial ischemia or Infarction[4]

Patients with long term drug intake such as steroids, antituberculous treatment (ATT), diuretics, antimetabolite or chemotherapy drugs

Patients who were regularly consuming alcohol – Alcohol dependence subjects - evidenced by history, liver function tests, and ultrasonography abdomen

Patients of lympho or myeloproliferative disorders

Patients who had chronic liver disease and metabolic disorders

Endocrine disorder – Hypothyroid patients

Psoriasis patients

Patients in whom BMI > 30.

Both the cases and controls selected were matched for age, sex and BMI. The subjects in our sample included both young and old (20–50 years), but most of the studies included only younger subjects. Data were entered in Microsoft excel spreadsheet and analyzed statistically using standard statistical software. Significance testing of the difference between means was done by unpaired two-tailed Student's t-test, and correlations were assessed by Pearson coefficient. Significance was considered if the “P” <0.05.

Results

Blood pressure in both controls and cases were measured and the mean BP in cases was 155/101 and in controls it was 113/74, respectively.

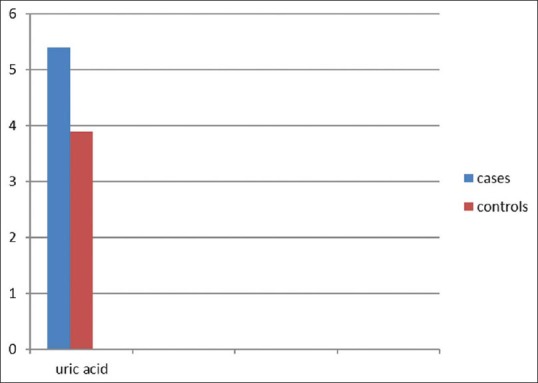

The mean plasma UA in cases was 5.4 ± 1.0 mg/dl (range: 3.0–8.2) and the mean plasma UA in controls was 3.9 ± 0.8 mg/dl (range: 3.0–7.2).

The association between UA and hypertension was analyzed using Student's t-test and statistical difference was assessed by Pearson coefficient. The study showed a significant difference between the hypertensive subjects and the normotensive controls (P = 0.021). If UA were simply a marker, then a similar degree of hyperuricemia in the control subjects would be expected, and this was not observed.

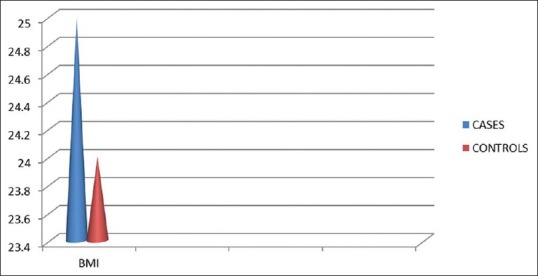

Though mean UA was higher is subjects with BMI > 25 than those subjects with BMI < 25 the relationship between UA and BMI[5] did not show a statistical difference in this study, but Nakanishi et al. found a stronger association among those with lower BMI.

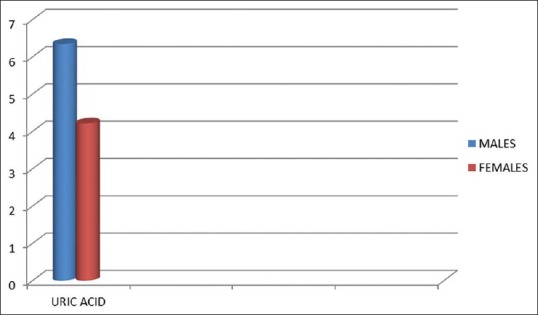

Males were found to be more hyperuricemic than females in the study in which the difference is significant (P = 0.02). 6.34 in male and 4.21 in females.

Many of the studies have showed that hyperuricemia is closely associated with waist abnormality. The study revealed that there was not a significant difference between waist abnormality and UA in cases (P = 0.49). The study also examined a possible relationship between smoking and hyperuricemia in hypertensive individuals. It was to observe that whether smoking influences hyperuricemia in hypertension. The study showed that there is no significant difference between smoking (present or absent) and hyperuricemia (P = 0.48).

The study also examined the relation between metabolic syndrome and UA. UA is associated with metabolic syndrome as indicated by various studies. It was also observed that a significant difference was obtained by the test between the two groups (P = 0.02). It is also to be noted that the sample size in both groups were small.

Out of 50 cases 30 subjects were found to have metabolic syndrome. Similarly, out of 50 controls 12 subjects were found to have the syndrome. The mean and standard deviation of UA in cases with metabolic syndrome is 6.02 and in controls it is 3.98. The statistical test shows a significant difference between the two groups with regard to metabolic syndrome (P = 0.034) as also evidenced by other studies [Figures 1–3].

Figure 1.

Uric acid levels in cases and controls

Figure 3.

Uric acid level in new hypertensive male and female

Figure 2.

BMI in cases and controls

Discussion

Hyperuricemia may be classified as primary or secondary. It is more useful to classify hyperuricemia in relation to the underlying pathophysiology, that is, whether it results from increased production, decreased excretion or a combination of the two. The concept that UA may be involved in hypertension is not a new one. In fact, in a paper published in 1879 that originally described essential hypertension, Frederick Akbar Mohamed noted that many of his subjects came from gouty families. He hypothesized that the UA might be integral to the development of essential hypertension.[6] Ten years later, this hypothesis reemerged when Haig[7] proposed low-purine diets as a means to prevent hypertension and vascular disease. In 1909, the French academician Henri Huchard noted that renal arteriolosclerosis (the histologic lesion of hypertension) was observed in three groups: Those with gout, those with lead poisoning, and those who have a diet enriched with fatty meat. All these groups are associated with hyperuricemia.[8] The association between elevated serum UA and hypertension was observed and reported repeatedly in the 1950s to 1980, but received relatively little sustained attention due to the lack of a mechanistic explanation. Twenty-five to 40% of adult patients with hypertension have hyperuricemia (>6.5 mg/dl), and this number increases dramatically when serum UA in the high-normal range is included.[3] In preeclampsia, the correlation between elevated serum UA and hypertension is > 70%[9] Despite these observations, the lack of a causal, mechanism led to mild elevations of serum UA being largely ignored in medical practice. The strength of the relationship between UA level and hypertension decreases with increasing patient age and duration of hypertension, suggesting that UA may be most important in younger subjects with early-onset hypertension. Cross-sectional studies have consistently noted that more than a quarter of patients with untreated hypertension have elevated serum UA.[10] Serum UA levels have also been associated cross-sectionally with BP[11] and longitudinally with hypertension incidence[5] and future increases in BP.[12] Experimental results indicate that mild hyperuricemia induces renal inflammation, activation of the renin-angiotensin system, and downregulation of nitric oxide (NO) production, all of which are potentially important pathways that lead to UA-mediated hypertension. In short, mild hyperuricemia leads to an irreversible salt-sensitive hypertension over time. Recent in vitro studies also have elucidated the possible mechanism of UA-mediated arteriolosclerosis. Primary human vascular smooth muscle cells are induced to proliferate by addition of UA to the growth medium in a dose-dependent manner.[13] The human smooth muscle cells express the urate-transport channel URAT1 as evidenced by both Northern and Western analyses. Addition of oxonic acid to cyclosporine treatment led to higher UA levels, more severe arteriolar hyalinosis, macrophage infiltration, and tubulointerstitial damage compared with rats that were treated with cyclosporine alone.[14]

Recent epidemiology: A change in perspective

Before 1990, only Kahn et al.[5] had reported that an increased serum UA is an independent risk factor for hypertension; however, it had been noted that 25–40% of adults with hypertension have serum UA > 6.5 mg/dl and > 60% have a serum UA > 5.5 mg/dl[3] and that there was a linear relationship between serum UA and systolic BP. The recent evaluation of a subset of the Framingham Heart Study found that serum UA level was an independent predictor of hypertension and BP progression over as little as 4 years an elevated UA level consistently predicts the development of hypertension.[5] An elevated UA level is observed in 25–60% of patients with untreated essential hypertension and in nearly 90% of adolescents with essential hypertension of recent onset.[11] Raising the UA level in rodents results in hypertension with the clinical, hemodynamic, and histologic characteristics of hypertension.[15] Reducing the UA level with xanthine oxidase inhibitors lowers BP in adolescents with hypertension of recent onset.

Hypertension in this model was mediated by two mechanisms.

Uric acid-induced renal vasoconstriction mediated by endothelial dysfunction with reduced NO levels and by activation of the renin-angiotensin system. This hypertension type is salt-resistant in that it 28 occurs even in the presence of a low-salt diet, and it responds to lowering of UA

Later, however, the hyperuricemia causes progressive renal microvascular disease (a lesion resembling arteriolosclerosis), and insufficient narrowing of the arteriolar lumen occurs, a component of the hypertension becomes salt-driven, renal-dependent, and independent of UA level.

The Bogalusa Heart study found that UA levels in childhood predict the development of diastolic hypertension 10 years later. The second study, from the Framingham group[16] also found UA to predict the development of hypertension. This latter study is all the more remarkable as it was performed in an older population (mean age 50) in which they first eliminated 25% of their subjects because they already had hypertension or gout, thereby removing a large proportion of their target population. Excessive intake of fructose or purine-rich meats or exposure to low doses of lead may result in chronic hyperuricemia. Mothers with high UA levels that are the result of diet or conditions such as preexisting hypertension, obesity, or preeclampsia may transfer UA into the fetal circulation through the placenta, which may ultimately contribute to intrauterine growth retardation (IUGR) and a reduction in nephron number. Among babies born with a low nephron number, hyperuricemia may develop in childhood because of genetic or environmental factors. Chronic hyperuricemia would stimulate the reninangiotensin system and inhibit the release of endothelial NO contributing to renal vasoconstriction and possibly increasing blood pressure. Persistent renal vasoconstriction may contribute to arteriolosclerosis and the development of salt-sensitive hypertension, even if the hyperuricemia is corrected.

The study was based on strong epidemiologic data that have linked serum UA to hypertension in humans[3,10,11,9] and experimental animal data, which suggest that hyperuricemia contributes to hypertension.[15] The experimental studies further demonstrated that hyperuricemia caused preglomerular vascular disease via a BP-independent pathway[15] and once vascular changes were established, the hypertension was driven by the kidney lowering UA levels was no longer protective.[15] It is, therefore, hypothesized that if serum UA were important in the genesis of primary hypertension, then the relation would be greatest in the new and recent onset hypertensive subjects.

Hypertension in humans

Excessive intake of fructose or purine-rich meats or exposure to low doses of lead may result in chronic hyperuricemia. Mothers with high UA levels that are the result of diet or conditions such as preexisting hypertension, obesity, or preeclampsia may transfer UA into the fetal circulation through the placenta, which may ultimately contribute to IUGR and a reduction in nephron number. Among babies born with a low nephron number, hyperuricemia may develop in childhood because of genetic or environmental factors. Chronic hyperuricemia would stimulate the reninangiotensin system and inhibit the release of endothelial NO contributing to renal vasoconstriction and possibly increasing BP. Persistent renal vasoconstriction may contribute to arteriolosclerosis and the development of salt-sensitive hypertension, even if the hyperuricemia is corrected.[12]

Conclusion

Males have a higher degree of hyperuricemia than females in hypertensive patients

Though mean UA is higher in study subjects whose BMI > 25 than those subjects with BMI < 25, the association is not significant

There is no stronger association of hyperuricemia in hypertension patients with regard to waist abnormality

There is no significant difference among hypertensive males with regard to UA and smoking. Smoking does not show an influence on hyperuricemia in cases

Hyperuricemia is associated with metabolic syndrome as evidenced by other studies.

There is a future perspective that hypertension can be treated by lowering UA levels particularly in new and recent onset.[17] Serum UA is strongly associated with BP in new and recent onset primary hypertension.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Chobanian AV, Bakris GL, Black HR, Cushman WC, Green LA, Izzo JL, Jr, et al. The seventh report of the joint national committee on prevention, detection, evaluation, and treatment of high blood pressure: The JNC 7 report. JAMA. 2003;289:2560–72. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.19.2560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Selby JV, Friedman GD, Quesenberry CP., Jr Precursors of essential hypertension: Pulmonary function, heart rate, uric acid, serum cholesterol, and other serum chemistries. Am J Epidemiol. 1990;131:1017–27. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a115593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cannon PJ, Stason WB, Demartini FE, Sommers SC, Laragh JH. Hyperuricemia in primary and renal hypertension. N Engl J Med. 1966;275:457–64. doi: 10.1056/NEJM196609012750902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Alderman MH, Cohen H, Madhavan S, Kivlighn S. Serum uric acid and cardiovascular events in successfully treated hypertensive patients. Hypertension. 1999;34:144–50. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.34.1.144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kahn HA, Medalie JH, Neufeld HN, Riss E, Goldbourt U. The incidence of hypertension and associated factors: The Israel ischemic heart disease study. Am Heart J. 1972;84:171–82. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(72)90331-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mohamed FA. On chronic Bright's disease, and its essential symptoms. Lancet. 1879;1:399–401. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Haig A. On Uric Acid and Arterial Tension. Br Med J. 1889;1:288–91. doi: 10.1136/bmj.1.1467.288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Huchard H. Arteriolosclerosis: Including its cardiac form. JAMA. 1909;53:1129–32. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Curtis JJ, Luke RG, Jones P, Diethelm AG. Hypertension in cyclosporine-treated renal transplant recipients is sodium dependent. Am J Med. 1988;85:134–8. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(88)80331-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Johnson RJ, Rodríguez-Iturbe B, Schreiner GF, Herrera-Acosta J. Hypertension: A microvascular and tubulointerstitial disease. J Hypertens Suppl. 2002;20:S1–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Feig DI, Johnson RJ. Hyperuricemia in childhood primary hypertension. Hypertension. 2003;42:247–52. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000085858.66548.59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Masuo K, Kawaguchi H, Mikami H, Ogihara T, Tuck ML. Serum uric acid and plasma norepinephrine concentrations predict subsequent weight gain and blood pressure elevation. Hypertension. 2003;42:474–80. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000091371.53502.D3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kang DH, Nakagawa T, Feng L, Watanabe S, Han L, Mazzali M, et al. A role for uric acid in the progression of renal disease. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2002;13:2888–97. doi: 10.1097/01.asn.0000034910.58454.fd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kang DH, Kim YG, Andoh TF, Gordon KL, Suga S, Mazzali M, et al. Post-cyclosporine-mediated hypertension and nephropathy: Amelioration by vascular endothelial growth factor. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2001;280:F727–36. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.2001.280.4.F727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mazzali M, Hughes J, Kim YG, Jefferson JA, Kang DH, Gordon KL, et al. Elevated uric acid increases blood pressure in the rat by a novel crystal-independent mechanism. Hypertension. 2001;38:1101–6. doi: 10.1161/hy1101.092839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sundström J, Sullivan L, D’Agostino RB, Levy D, Kannel WB, Vasan RS. Relations of serum uric acid to longitudinal blood pressure tracking and hypertension incidence. Hypertension. 2005;45:28–33. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000150784.92944.9a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gruskin AB. The adolescent with essential hypertension. Am J Kidney Dis. 1985;6:86–90. doi: 10.1016/s0272-6386(85)80146-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]