Abstract

Background and Purpose

Nicotine dose-dependently activates or preferentially desensitizes β2 subunit containing nicotinic ACh receptors (β2*nAChRs). Genetic and pharmacological manipulations assessed effects of stimulation versus inhibition of β2*nAChRs on nicotine-associated anxiety-like phenotype.

Experimental Approach

Using a range of doses of nicotine in β2*nAChR subunit null mutant mice (β2KO; backcrossed to C57BL/6J) and their wild-type (WT) littermates, administration of the selective β2*nAChR agonist, 5I-A85380, and the selective β2*nAChR antagonist dihydro-β-erythroidine (DHβE), we determined the behavioural effects of stimulation and inhibition of β2*nAChRs in the light–dark and elevated plus maze (EPM) assays.

Key Results

Low-dose i.p. nicotine (0.05 mg·kg−1) supported anxiolysis-like behaviour independent of genotype whereas the highest dose (0.5 mg·kg−1) promoted anxiogenic-like phenotype in WT mice, but was blunted in β2KO mice for the measure of latency. Administration of 5I-A85380 had similar dose-dependent effects in C57BL/6J WT mice; 0.001 mg·kg−1 5I-A85380 reduced anxiety on an EPM, whereas 0.032 mg·kg−1 5I-A85380 promoted anxiogenic-like behaviour in both the light–dark and EPM assays. DHβE pretreatment blocked anxiogenic-like effects of 0.5 mg·kg−1 nicotine. Similarly to DHβE, pretreatment with low-dose 0.05 mg·kg−1 nicotine did not accumulate with 0.5 mg·kg−1 nicotine, but rather blocked anxiogenic-like effects of high-dose nicotine in the light–dark and EPM assays.

Conclusions and Implications

These studies provide direct evidence that low-dose nicotine inhibits nAChRs and demonstrate that inhibition or stimulation of β2*nAChRs supports the corresponding anxiolytic-like or anxiogenic-like effects of nicotine. Inhibition of β2*nAChRs may relieve anxiety in smokers and non-smokers alike.

Tables of Links

| TARGETS |

|---|

| Ligand-gated ion channels |

| β2* nAChRs, nicotinic ACh receptors |

| LIGANDS |

|---|

| DHβE, dihydro-β-erythroidine |

| Varenicline |

| 5-iodo-A85380 |

These Tables list key protein targets and ligands in this article which are hyperlinked to corresponding entries in http://www.guidetopharmacology.org, the common portal for data from the IUPHAR/BPS Guide to PHARMACOLOGY (Pawson et al., 2014) and are permanently archived in the Concise Guide to PHARMACOLOGY 2013/14 (Alexander et al., 2013).

Introduction

Nicotine, found in tobacco and e-cigarettes, both stimulates and inhibits the function of neuronal nicotinic ACh receptors (nAChRs) (Lester and Dani, 1995; Fenster et al., 1997; Pidoplichko et al., 1997; Mansvelder et al., 2002). In vitro and in vivo studies show that nicotine both activates and desensitizes nAChR ion channels, and that low concentrations may preferentially desensitize nAChRs, rendering them unavailable for further activation by nicotine or the endogenous neurotransmitter ACh (Lester and Dani, 1995; Fenster et al., 1997; Pidoplichko et al., 1997; Mansvelder et al., 2002; Buccafusco et al., 2007). This modulation of nAChRs in brain can lead to a range of psychoactive effects (Tsuda et al., 1996; Grillon et al., 2007; Gilbert et al., 2008; Evatt and Kassel, 2010). Although more studies are needed to assess motives for e-cigarette nicotine vaping, many smokers of traditional cigarettes indicate that they smoke to relieve anxiety (Perkins and Grobe, 1992; Fidler and West, 2009). Stress is a major precipitating factor in smoking relapse (Shiffman et al., 1997) and for escalation of cigarette use (Skara et al., 2001), further suggesting that smoking relieves anxiety. High doses of nicotine or repeated exposure may also promote anxiety as other studies suggest that smokers experience anxiety more intensely than non-smokers (Perkins and Grobe, 1992; Parrott, 1999; Fidler and West, 2009). The contributions of specific nAChR subtypes to anxiety behaviours are not clearly understood.

Evidence from animal models of anxiety-like behaviour suggests that selective inhibition of β2 subunit containing nicotinic ACh receptors (β2*nAChRs) reduces anxiety phenotype (Turner et al., 2010; Anderson and Brunzell, 2012; Hussmann et al., 2014). In addition to their localization in mesolimbic areas that support motivational valence for aversion and reward, β2*nAChRs are present in limbic brain areas where they might also contribute to anxiety-like behaviour (e.g. Mineur et al., 2009). When administered systemically, compounds that inhibit β2*nAChRs promote anxiolysis-like behaviour (Turner et al., 2010; Anderson and Brunzell, 2012). Sazetidine-A, a partial agonist of β2*nAChRs with antagonist properties at the high-sensitivity α42β23* nAChR confirmation, results in reduced digging behaviour in the marble-burying assay and reduced latencies to consume a palatable food in a novel environment (Turner et al., 2010). The selective β2*nAChR antagonist dihydro-β-erythroidine (DHβE) similarly increases time spent in open arms of the elevated plus maze (EPM), decreases digging in a marble-burying task and reduces conditioned inhibition in response to an aversive cue (Anderson and Brunzell, 2012). Interestingly, low doses of nicotine have a similar effect to decrease anxiety behaviours in these ethological and learned models (File et al., 1998; McGranahan et al., 2011; Anderson and Brunzell, 2012; Varani et al., 2012), whereas high doses of nicotine promote anxiety behaviours in rodent behavioural assays of anxiety-like behaviour (File et al., 1998; Ouagazzal et al., 1999a; Cheeta et al., 2001; Zarrindast et al., 2008; Varani et al., 2012). Together, these electrophysiology and behavioural findings suggest that low doses of nicotine may promote anxiolysis via inhibition of the high-affinity β2*nAChRs, but this has not been directly tested.

Using the light–dark and EPM assays, rodent models with good predictive validity for FDA-approved pharmacological agents for treatment of anxiety in humans (Crawley and Goodwin, 1980; Wiley et al., 1995), these studies (i) utilized β2*nAChR null mutant mice (β2KO) to determine if β2*nAChRs are necessary for expression of the anxiolytic-like and anxiogenic-like effects of nicotine; (ii) utilized the selective β2*nAChR agonist 5-iodo-A85380 (5I-A85380) to determine if dose effects were similar to nicotine to suggest that β2*nAChRs are sufficient to promote anxiolysis at low doses and anxiogenesis at high doses; (iii) expanded upon previous data to test if pre-injection of the selective β2*nAChR antagonist, DHβE, would augment anxiolytic-like effects of low dose nicotine or block anxiogenic-like effects of high-dose nicotine; and (iv) specifically tested if pretreatment with low-dose nicotine could effectively block the anxiogenic-like effects of high-dose nicotine.

Methods

Animals

All animal care and experimental procedures were in compliance with the NIH Guide for Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and were approved by the Virgina Commonwealth University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. All studies involving animals are reported in accordance with the ARRIVE guidelines for reporting experiments involving animals (Kilkenny et al., 2010; McGrath et al., 2010). A total of 169 animals were used in the experiments described here.

One hundred sixty-nine adult male C57BL/6J wild-type (WT) and 42 β2KO mice (Picciotto et al., 1995) backcrossed for more than 10 generations to a C57BL/6J background (27–32 g; derived from heterozygous matings) were used for these studies. Littermates were used where possible with groups balanced by weight. Genotypes were confirmed as described previously (Salminen et al., 2004). A subset of mice in pharmacological studies were acquired from Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME, USA). Animals (aged 4–8 months) were group-housed (two to five per cage), maintained in an AAALAC-approved facility on a 12 h light/dark cycle and provided ad libitum access to food and water. Experiments were conducted during the light cycle. Mice were habituated to experimenter handling for at least 3 days and to the experimental room for 1 day prior to experimentation. Every effort was taken to minimize mouse pain or discomfort and to reduce animal numbers.

Apparatus

Light–dark experiments were conducted in modified place conditioning chambers (Med Associates, St. Albans, VT, USA). A small, enclosed, dark chamber with a black ceiling (L 16.8 cm × W 12.7 cm × H 12.7 cm) was directly adjacent to a larger, open, brightly lit chamber (L 26.5 cm × W 12.7 cm × H 26.2 cm) illuminated by a 23 W fluorescent bulb. An opening (W 5 cm × H 5.9 cm) enabled mice to move freely throughout the apparatus. Photocells placed 3 cm apart recorded mouse location and movement. Data were collected on a personal computer (PC) and calculated using MED-PC software (Med Associates).

An EPM 68 cm above the floor was constructed of wood with white plastic flooring on two (5 × 30 cm) open arms that were perpendicular to two equivalent arms enclosed by 15.25 cm black Plexiglas walls. Experiments were conducted under fluorescent illumination. A ceiling-mounted camera interfaced to a PC collected data using ANY-maze tracking software (Stoelting, Wood Dale, IL, USA).

An infrared camera interfaced to ANY-maze tracked open-field behaviour, which took place in 33 × 21 × 9 cm Plexiglas chambers. A 23 W bulb, 3 m from the apparatus, provided lighting.

A Roto-Rod Series 8 unit for mice (IITC Inc. Life Science, Woodland Hills, CA, USA) apparatus was programmed to accelerate from 0 to 200 r.p.m. in 300 s.

Behavioural procedures

Experiment 1: genetic assessment of β2*nAChR contributions to light–dark behaviour

The experimental room was dark other than illumination from the light–dark apparatus. β2KO and WT mice received between-subject delivery of sterile saline (VEH), 0.01, 0.05, 0.1 or 0.5 mg·kg−1 i.p. nicotine (WT n = 12, 13, 10, 9, 9; β2KO n = 12, 10, 12, 10, 12, respectively, for each dose and genotype) immediately prior to placement in the dark chamber for 10 min of observation. Time spent in the light chamber and short latencies to leave the dark chamber were interpreted as anxiolytic-like behaviours whereas long latencies and little time spent in the light chamber relative to controls were interpreted as anxiogenic-like behaviours in this ethological task (Crawley and Goodwin, 1980). Drug effects on horizontal activity were determined by number of movement counts, requiring two adjacent photocell beam breaks. Chambers were wiped with 2% Nolvasan (Pfizer Animal Health, Madison, NJ, USA) between trials.

Experiments 2 and 3: evaluation of selective β2*nAChR agonist 5I-A85380 on anxiety-like behaviour in the light–dark and EPM assays

C57BL/6J male mice received between-subject delivery of VEH, 0.001, 0.0032, 0.01 or 0.032 mg·kg−1 i.p. 5I-A85380 15 min prior to behavioural evaluation in the light–dark assay (n = 9 VEH and eight per other doses), as described earlier, or the EPM assay (n = 8 per dose). Mice were placed at the centre of the EPM facing the closed arms and tested for 10 min. A continuum of anxiety behaviour was assessed via time spent in the closed arms (anxiogenic-like behaviour) and time spent in the open arms, open-arm entries and short latencies to explore the terminal 5 cm of the open arms (anxiolysis-like behaviour) relative to control mice (Wiley et al., 1995; Dalvi and Rodgers, 1996). Closed-arm entries evaluated non-specific drug effects on horizontal activity.

Experiment 4: pharmacological assessment of β2*nAChR contributions to light–dark behaviour

Light–dark procedures were as described for experiment 1 except that C57BL/6J mice received pre-injection of VEH or 2 mg·kg−1 i.p. DHβE 15 min prior to VEH, low-dose (0.05 NIC; 0.05 mg·kg−1) or high-dose (0.5 NIC; 0.5 mg·kg−1) nicotine (n = 11 VEH/VEH, 11 VEH/0.05 NIC, 9 VEH/0.5 NIC; 8 DHβE/VEH, 8 DHβE/0.05 NIC, 9 DHβE/0.5 NIC). This dose of DHβE has been shown previously to block nicotine-conditioned place preference (CPP), which requires activation of β2*nAChRs (Walters et al., 2006). VEH/VEH mice were run concomitantly in experiments 4 and 5 to conserve mice.

Experiments 5 and 6: evaluation of low-dose nicotine pretreatment on nicotine-associated anxiogenic-like and anxiolytic-like behaviour in the light–dark and EPM assays

Light–dark procedures were as described for experiment 1, except that mice received pre-injection of VEH, 0.01 mg·kg−1 i.p. nicotine (0.01 NIC) or 0.05 NIC 10 min prior to low dose (0.05 mg·kg−1) or high-dose (0.5 mg·kg−1) i.p. nicotine (n = 9 VEH/VEH, 10 VEH/0.05 NIC, 9 VEH/0.5 NIC, 8 0.01 NIC/0.05 NIC, 8 0.01 NIC/0.5 NIC, 7 0.05 NIC/0.05 NIC, 8 0.05 NIC/0.5 NIC).

EPM procedures were as described in experiment 3 except that mice received a pre-injection of VEH, 0.01 or 0.05 mg·kg−1 i.p. nicotine 10 min before 0 or 0.5 mg·kg−1 i.p. nicotine (n = 10 VEH/VEH, 10 0.01 NIC/VEH, 10 0.05 NIC/VEH, 11 VEH/0.5 NIC, 12 0.01 NIC/0.5 NIC, 13 0.05 NIC/0.5 NIC).

Experiments 7 and 8: assessment of high-dose nicotine and 5I-A85380 effects on rotorod and dim lighting open-field behaviour

Mice were assessed for potential motor impairments of high-dose nicotine and 5IA-85380 using a within-subject design for the rotorod and open-field tests. Independent groups of drug-naive mice were habituated to the rotorod apparatus to reliably achieve at least 60 s without falling. For testing, baseline was established followed by VEH or 0.5 mg·kg−1 nicotine (group A, n = 10) or VEH or 0.032 mg·kg−1 5I-A85380 (group B, n = 9) i.p., injection with testing at 1 and 10 min post-injection (balanced by baseline performance). Rods were cleaned with Nolvasan between mouse runs. Twenty-four hours later, mice were tested with VEH or drug, whichever they had not received the previous day.

One week later, open-field procedures took place for 15 min under low-light illumination to assess locomotor behaviour under minimal anxiety-provoking conditions. To further reduce anxiety, mice were habituated to the chamber and injections over 3 days of exposure prior to testing and then received VEH or drug in a counterbalanced fashion over 2 days as described for rotorod with groups A and B reversed. Chambers were cleaned with Nolvasan between mice.

Statistical analysis

Two-way, between-subject anova tested genotype × nicotine dose (2 × 5), and pretreatment × nicotine dose (2 × 3) interactions in experiments 1, 4 and 6. One-way anova compared groups in experiments 2, 3 and 5. Planned comparisons assessed the stress of multiple injections by comparing no inj/VEH to VEH/VEH WT controls. Dunnett's post hoc tests assessed significant main effects in comparison to VEH controls. Post hoc t-tests assessed significant interactions. P values < 0.05 were reported as significant.

Materials

Nicotine hydrogen tartrate (Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA), DHβE and 5I-A85380 (Tocris, Bristol, UK) were diluted in 0.9% sterile saline vehicle (VEH). Injections were delivered i.p. in volumes of 0.1 mL per 30 g. Doses are expressed as weights of the free base. Drug target nomenclature is according to the BJP Concise Guide to Pharmacology (Alexander et al., 2013).

Results

Experiment 1: genetic evidence of β2*nAChR contributions to light–dark behaviour

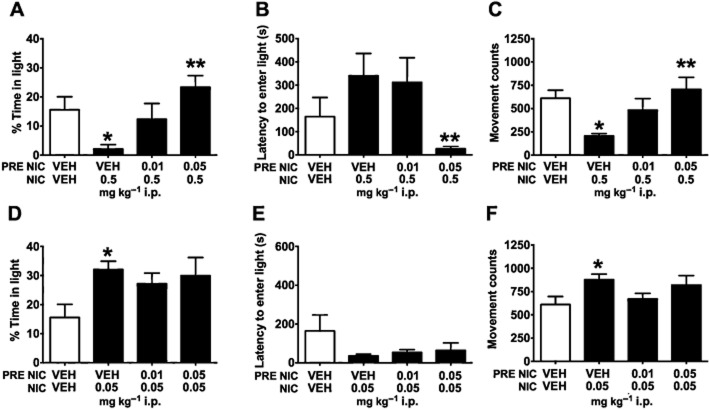

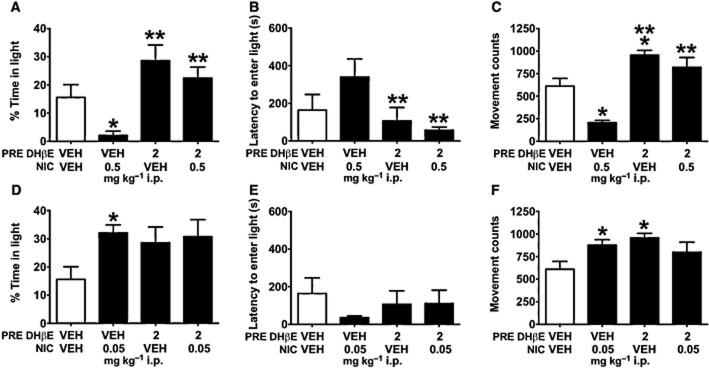

Consistent with an anxiolytic-like phenotype, a main effect of nicotine treatment (F4,99 = 15.790, P < 0.001) revealed that mice receiving a low dose of nicotine (0.05 mg·kg−1) spent more time in the light chamber compared with VEH-injected controls (P < 0.05; Figure 1A). In contrast, mice given the highest dose of nicotine (0.5 mg·kg−1) spent significantly less time in the light chamber compared with VEH controls (P < 0.001), suggestive of anxiogenic-like behaviour. Although time spent in the light did not reveal a significant difference between genotypes, there was a significant genotype × treatment interaction for latency (F4,99 = 2.680, P = 0.036) revealing a blunted ability of high-dose nicotine to increase anxiety in β2KO mice. At the 0.5 mg·kg−1 dose, β2KO mice exhibited shorter latencies to enter the light chamber compared with their WT littermates (t19 = 2.171, P = 0.043; Figure 1B). WT mice receiving 0.5 mg·kg−1 nicotine required significantly more time to enter the light chamber than their saline-injected counterparts (t19 = 3.908, P = 0.001; Figure 1B); β2KO mice injected with 0.5 mg·kg−1 nicotine; however, did not differ from VEH-injected β2KO controls (t22 = 1.822, P = 0.082; Figure 1B). A main effect of drug treatment (F4,99 = 14.900, P < 0.001) was observed for movement counts. Mice given 0.5 mg·kg−1 nicotine showed reduced horizontal movement compared with controls (P < 0.001), but there was no genotype × dose interaction on this measure. Together, these findings suggest that β2*nAChRs as well as non-β2*nAChRs contributed to anxiety behaviours observed in the light–dark assay.

Figure 1.

Genetic evidence that β2*nAChRs contribute to anxiogenic-like effects of nicotine. Results shown are from WT and β2KO mice. (A) As predicted, nicotine treatment had a dichotomous effect on anxiety-like behaviour. A low dose of nicotine (0.05 mg·kg−1 i.p.) increased time spent in the light chamber, suggestive of a an anxiolytic-like phenotype, and a high dose (0.5 mg·kg−1 i.p.) decreased time in the light chamber, suggestive of an anxiogenic-like phenotype. (B) For latency, mice, receiving high-dose nicotine required more time to enter the light chamber than their respective saline-treated controls, an effect that was blunted in β2KO mice, demonstrating that β2*nAChRs contribute to this measure. (C) Compared with VEH controls, mice treated with 0.5 mg·kg−1 i.p. nicotine showed reduced movement counts independent of genotype, suggesting that nicotinic receptor subtypes other than β2*nAChRs contributed to reduced horizontal activity in this task. Data are represented as means ± SEM. *P < 0.05 compared with saline-treated mice of same genotype, **P < 0.05 compared with WT mice receiving the same dose.

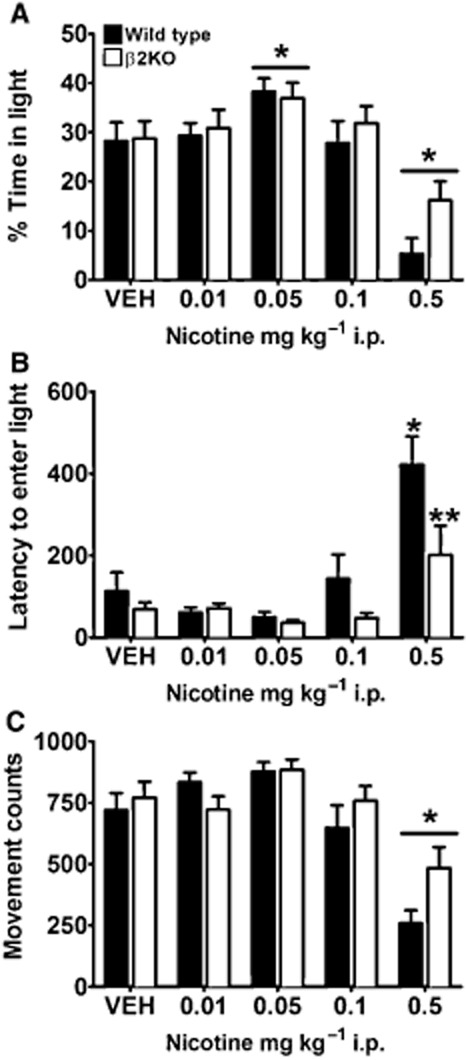

Experiments 2 and 3: β2*nAChRs are sufficient to support anxiolysis-like and anxiogenic-like EPM and anxiogenic-like light–dark behaviour

For the light–dark assay, there was a main effect of drug administration for percentage of time spent in the light chamber (F4,36 = 5.120, P = 0.002) and latency to enter the light chamber (F4,36 = 17.453, P < 0.001). Consistent with activation of β2*nAChRs supporting anxiogenic phenotype, post hoc tests revealed that mice treated with 0.032 mg·kg−1 5I-A85380 spent less time in the light chamber (P = 0.005; Figure 2A) and showed increased latencies to enter the light chamber than VEH-injected mice (P < 0.001; Figure 2B). A main effect of treatment observed for movement counts (F4,36 = 5.014, P = 0.003) revealed that mice injected with 0.032 mg·kg−1 5I-A85380 showed reduced horizontal activity compared with saline-injected controls (P = 0.003; Figure 2C), suggesting that β2*nAChRs also contributed to locomotor activity or exploration in this task.

Figure 2.

Administration of the selective β2*nAChR agonist 5I-A85380 results in anxiogenic-like behaviour in the light–dark assay. (A) Mice administered 0.032 mg·kg−1 i.p. of the selective β2*nAChR agonist 5-Iodo-A85380 (5I-A85380) spent less time in the light chamber, (B) showed longer latencies to enter the light chamber and (C) showed less horizontal activity than mice receiving saline VEH. Data are reported as means ± SEM; *P < 0.05 compared with saline VEH.

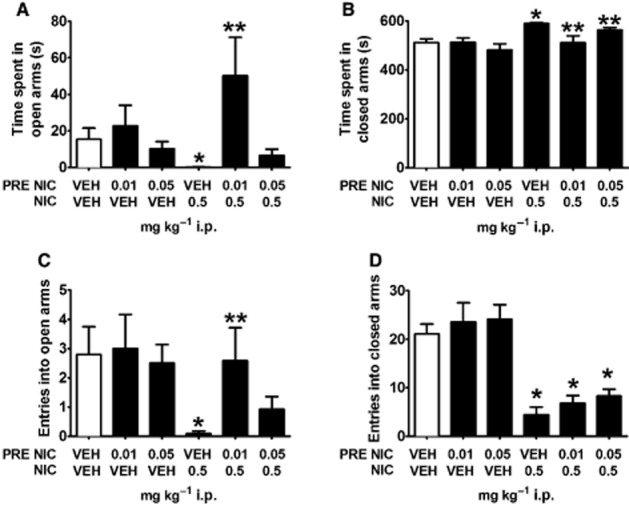

Similar to previous reports for nicotine in the EPM (McGranahan et al., 2011; Varani et al., 2012), low-dose 5I-A85380 supported anxiolysis-like behaviour and mice injected with high-dose 5I-A85380 showed anxiogenic-like behaviour. Mice showed main effects of drug treatment for time spent in the open arms (F4,35 = 4.254, P = 0.007), time spent in the closed arms (F4,35 = 7.946, P < 0.001) and number of entries into the open arms (F4,35 = 5.131, P = 0.002). Compared with saline-injected controls, mice injected with low-dose 0.001 mg·kg−1 5I-A85380 spent more time in the open arms and made more entries into the open arms (P < 0.05; Figure 3A, P < 0.05; Figure 3C), whereas administration of a high dose of 0.032 mg·kg−1 5I-A85380 resulted in increased time spent in the closed arms of an EPM compared with control mice (P < 0.05; Figure 3B). Dunnett's tests of latencies to explore the terminal 5 cm of the open arms (F4,35 = 4.728, P = 0.004) failed to reach significance because of variability of control mice for this measure (Table 1). Although there was an effect of closed-arm entries (F4,35 = 3.129, P = 0.027), post hoc tests did not detect any effect of 5I-A85380 dose compared with controls on entries made into the closed arms to suggest that β2*nAChRs significantly affected locomotor activity in this task. In the light–dark and EPM assays, 5I-A85380 supported anxiogenic-like behaviours at the highest dose. The lowest dose of 5I-A85380 supported anxiolysis-like behaviour in the EPM task. Together these findings suggest that the contributions of β2*nAChRs to anxiety behaviour are dose- and task-sensitive.

Figure 3.

Administration of selective β2*nAChR agonist 5I-A85380 has a bimodal effect on anxiety-like behaviour in EPM assay. (A) Mice receiving a low dose (0.001 mg·kg−1 i.p.) of 5I-A85380 spent more time in the open arms of an EPM, and (C) made more entries into the open arms than saline-injected mice, indicative of anxiolytic-like behaviour, (B) whereas mice injected with a high dose (0.032 mg·kg−1 i.p.) of 5I-A85380 spent more time in the closed arms than VEH-injected controls, indicative of anxiogenic-like behaviour. (D) There was no effect of 5I-A85380 on closed-arm entries to suggest non-specific effects of 5I-A85380 on locomotor behaviour. Data are reported as means ± SEM; *P < 0.05 compared with saline VEH.

Table 1.

Latency to open arm terminus following 5I-A85380 administration

| Dose 5I-A85380 (mg·kg−1 i.p.) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VEH | 0.001 | 0.0032 | 0.01 | 0.032 | |

| Mean ± SEM (s) | 427.5 ± 84.6 | 248.5 ± 63.1 | 323.7 ± 81.8 | 534.0 ± 66.0 | 600 ± 0.0 |

| Mice to reach terminus | 38% | 88% | 63% | 13% | 0% |

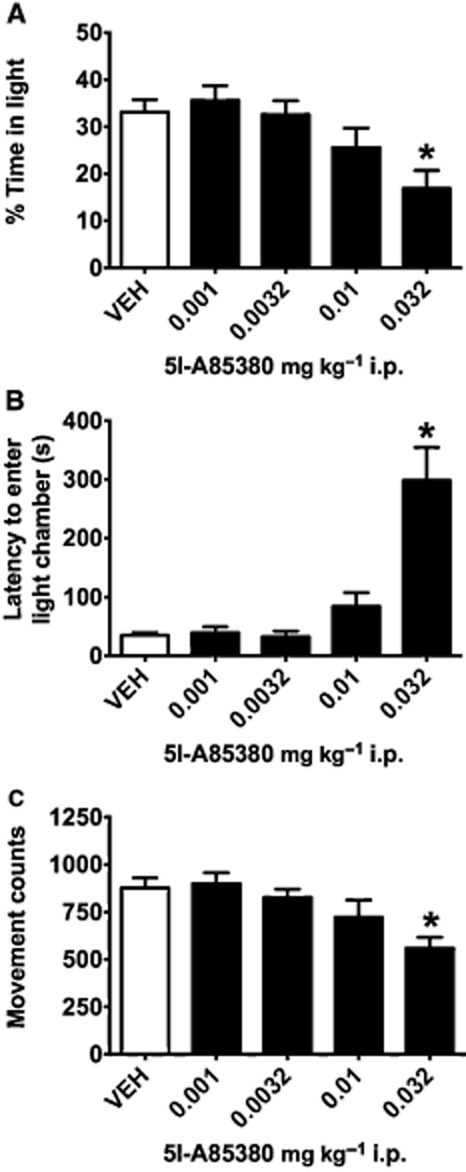

Experiment 4: the β2*nAChR antagonist DHβE blocks nicotine-associated light–dark anxiogenic behaviour

The two injections required for this procedure increased anxiety-like behavioural measures as shown by a significant reduction of time spent in the light chamber for control mice that received two saline injections (VEH/VEH; 15.6 ± 4.5 s) compared with control mice that received only one saline injection (NO INJ/VEH; 28.3 ± 3.6 s) (Supporting Information Table S1); but this added stressor did not preclude observation of anxiogenic or anxiolytic effects of nicotine on percentage of time in the light chamber. Planned comparisons revealed that mice receiving saline pre-injection before 0.5 mg·kg−1 nicotine (VEH/0.5 NIC) spent significantly less time in the light chamber than mice administered saline followed by another saline VEH injection (VEH/VEH; t16 = 2.859, P = 0.011; Figure 4A). As expected, mice treated with 0.05 mg·kg−1 low-dose nicotine following saline pre-injection (VEH/0.05 NIC) spent more time in the light chamber (t17 = 3.178, P = 0.006; Figure 4D) compared with VEH/VEH mice. Latencies did not differ between VEH/VEH and VEH/0.5 NIC or VEH/0.05 NIC (P's > 0.1; Figure 4B,E).

Figure 4.

Selective antagonism of β2*nAChRs via pretreatment with DHβE (PRE DHβE) blocks the anxiogenic-like effects of nicotine (NIC) in the light–dark assay. (A) Mice receiving saline pre-injection prior to high-dose nicotine (VEH/0.5 NIC) spent less time in the light chamber than mice given saline VEH only (VEH/VEH). A pre-injection of 2 mg·kg−1 i.p. DHβE effectively blocked this anxiogenic-like effect of 0.5 mg·kg−1 i.p. nicotine treatment (DHβE/0.5 NIC); DHβE/0.5 NIC mice spent significantly more time in the light chamber and (B) showed shorter latencies to enter the light chamber than VEH/0.5 NIC mice. (C) Pre-injections of DHβE also blocked high-dose nicotine-associated reductions in movement counts. DHβE/0.5 NIC mice showed significantly greater horizontal activity than VEH/0.5 NIC mice. (D) VEH/0.05 mg·kg−1 i.p. mice showed elevated time spent in the light chamber compared with VEH/VEH mice. This anxiolytic-like effect was not impacted by pre-injection of 2 mg·kg−1 i.p. DHβE, suggesting that the anxiolytic-like effects of low-dose nicotine do not require activation of β2*nAChRs. (E) Neither low-dose nicotine nor DHβE affected latency to enter the light chamber, (F) but both VEH/0.05 NIC and DHβE/VEH mice showed increased movement counts compared with controls. Data are reported as means ± SEM; *P < 0.05 compared with VEH/VEH; **P < 0.05 compared with VEH/0.5 NIC.

Experiment 4 evaluated whether selective antagonism of β2*nAChRs augments or reduces anxiogenic-like effects of 0.5 mg·kg−1 high-dose nicotine and anxiolytic-like effects of 0.05 mg·kg−1 low-dose nicotine. A DHβE pretreatment × nicotine dose interaction (F2,47 = 3.553, P = 0.037) revealed that pre-injections of DHβE blocked the anxiogenic-like effects of 0.5 mg·kg−1 nicotine as measured by increased time spent in the light chamber of DHβE/0.5 NIC compared with VEH/0.5 NIC mice (t16 = 4.890, P < 0.001; Figure 4A). A significant DHβE pretreatment × nicotine dose interaction (F2,47 = 3.687, P = 0.033) revealed that DHβE/0.5 NIC mice also showed decreased latencies to enter the light chamber compared with VEH/0.5 NIC mice (t16 = 2.913, P = 0.01; Figure 4B). Unlike anxiogenic-like effects of high-dose nicotine, the anxiolytic-like effects of low-dose nicotine were neither augmented nor blocked by pre-injection of DHβE (t's < 1). A pre-injection × nicotine dose interaction was detected for movement counts (F2,47 = 10.020, P < 0.001). DHβE pretreatment blocked the effects of 0.5 mg·kg−1 nicotine on reduced horizontal activity, as evidenced by significantly greater movement counts in DHβE/0.5 animals than VEH/0.5 NIC mice (t16 = 5.571, P < 0.001; Figure 4C). Additionally, DHβE/VEH mice showed increased movement counts compared with VEH/VEH mice (t15 = 3.353, P = 0.004; Figure 4C); 2 mg·kg−1 DHβE did not significantly affect latency or percentage of time in the light chamber.

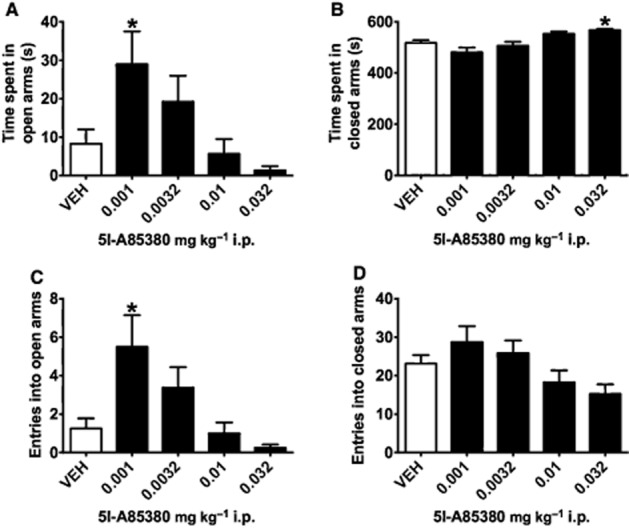

Experiments 5 and 6: low-dose nicotine pretreatment blocks nicotine-associated anxiogenic light–dark and EPM behaviour

A time course testing the effect of low-dose nicotine pre-injection on the anxiogenic effects of nicotine in the light–dark assay showed that pre-injection with low-dose nicotine blocked the anxiogenic effects of high-dose nicotine when given 10 min, but not 5 min, prior to subsequent nicotine injection (Supplementary Table S1). Data below reflect 10 min pre-injections. Treatment effects for time spent in the light chamber (F6,53 = 7.150, P < 0.001) and latency to enter the light chamber (F6,53 = 4.330, P = 0.001) reflected that, similar to pre-injection with DHβE, 0.05 mg·kg−1 nicotine pretreatment blocked anxiogenic-like effects of high-dose nicotine: 0.05 NIC/0.5 NIC mice demonstrated significant elevations of time spent in the light chamber and reduced latencies to enter the light chamber compared with VEH/0.5 NIC injected mice (P = 0.011; P = 0.019; Figure 5A,B). Anxiolysis-like effects of low-dose nicotine on time spent in the light chamber were neither augmented nor blocked by pretreatment with 0.01 or 0.05 mg·kg−1 nicotine (P's > 0.1; Figure 5D). One-way anova tests further revealed a main effect of treatment for total movement counts (F6,53 = 7.030, P < 0.001), as VEH/0.5 NIC mice showed reduced locomotor activity compared with VEH/VEH controls (P = 0.024; Figure 5C), an effect that was reversed by pre-treatment with 0.05 mg·kg−1 nicotine (P = 0.003; Figure 5C). Together these data demonstrate that pre-injection of nicotine did not accumulate with experimental doses to produce its effects, but rather appeared to act like an antagonist when given at low doses, 10 min prior to administration of an anxiogenic dose of nicotine.

Figure 5.

Pretreatment with an anxiolytic-like low dose of nicotine (PRE NIC) blocks rather than accumulates with an anxiogenic-like high dose of nicotine (NIC) in the light–dark assay. (A) Pretreatment with an anxiolytic-like dose of 0.05 mg·kg−1 i.p. nicotine blocked the anxiogenic-like effects of high-dose nicotine (0.05 NIC/0.5 NIC) as measured by more time spent in the light chamber (B) and less time required to enter the light chamber than mice pre-injected with saline VEH prior to an anxiogenic dose of 0.5 mg·kg−1 nicotine (VEH/0.5 NIC). (C) Pre-injections of 0.05 mg·kg−1 nicotine also blocked nicotine-induced reductions in horizontal activity. (D) Nicotine pretreatment did not significantly affect the percentage of time spent in the light chamber, (E) latencies to enter the light chamber or (F) horizontal activity in the light–dark assay. Data are reported as means ± SEM; *P < 0.05 compared with VEH/VEH; **P < 0.05 compared with VEH/0.5 NIC.

In the EPM assay, there was a main effect of anxiogenic nicotine injection on time spent in the closed arms (F1,60 = 11.509, P = 0.001) with a nearly significant interaction of nicotine pre-injection × anxiogenic nicotine dosing for this measure (F2,60 = 3.049, P = 0.055). VEH/0.5 NIC mice spent significantly more time in the closed arms than VEH/VEH controls (t19 = 5.104, P < 0.001; Figure 6B), an effect reversed by pretreatment with low-dose nicotine. Both 0.01 NIC/0.5 NIC and 0.05 NIC/0.5 NIC mice spent less time in the closed arms compared with VEH/0.5 mice (t21 = 2.591, P = 0.017; t22 = 2.200, P = 0.039; Figure 6B). A main effect of nicotine injection was also observed for open arm entries (F1,60 = 5.536, P = 0.022), with VEH/0.5 NIC mice making significantly fewer entries into the open arms than VEH/VEH controls (t19 = 3.012, P = 0.007). Pre-injection of 0.01 mg·kg−1 nicotine blocked this anxiogenic effect, as 0.01 NIC/0.5 NIC mice made more entries into the open arms than VEH/0.5 NIC mice (t21 = 2.112, P = 0.047; Figure 6C). Planned comparisons revealed that VEH/0.5 NIC mice spent significantly less time in the open arms (t19 = 2.627, P = 0.017) and showed increased latencies to explore the terminal 5 cm of the open arms (t19 = 2.051, P = 0.054) than VEH/VEH mice (Table 2 ). A main effect of nicotine pre-injection was also detected for time spent in the open arms (F2,60 = 4.643, P = 0.013); 0.01 NIC/0.5 NIC mice spent more time in the open arms than VEH/0.5 NIC mice (t21 = 2.294, P = 0.032; Figure 6A), revealing an anxiolytic-like effect of nicotine pre-injection. There was no effect of nicotine pretreatment on latency to explore the terminal 5 cm of the open arms (F1,60 = 1.306, P = 0.258). An effect of nicotine injection (F1,60 = 77.440, P < 0.001), but not of nicotine pre-treatment (F2,60 = 1.181, P = 0.314) on the number of closed-arm entries was observed. Neither 0.01 NIC/0.5 NIC mice nor 0.05 NIC/0.5 NIC mice differed significantly from VEH/0.5 NIC mice in this measure (P's > 0.1).

Figure 6.

Pre-injection of low-dose nicotine reverses anxiogenic-like effects of high-dose nicotine during EPM assay. (A–C) Mice injected with 0.5 mg·kg−1 i.p. nicotine (VEH/0.5 NIC) spent less time in the open arms, more time in the closed arms and made fewer entries into the open arms of an EPM than saline-injected controls (VEH/VEH), demonstrating an anxiogenic-like effect of high-dose nicotine in this task. Pre-injections of 0.01 mg·kg−1 i.p. nicotine blocked this effect, as 0.01 NIC/0.5 NIC mice (A) spent significantly more time in the open arms and (B) less time in the closed arms and made more open-arm entries than VEH/0.5 NIC mice. These data suggest that pre-injections of low-dose nicotine effectively block the anxiogenic-like effects of 0.5 mg·kg−1 i.p. nicotine in an EPM assay. (D) Nicotine pretreatment did not block reductions in closed-arm entries observed in VEH/0.5 mice. Data are reported as means ± SEM. *P < 0.05 compared with VEH/VEH; **P < 0.05 compared with VEH/0.5 NIC.

Table 2.

Latency to open arm terminus

| Pre- and post-treatment of mg·kg−1 i.p. nicotine | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VEH/VEH | 0.01 NIC/VEH | 0.05 NIC/VEH | VEH/0.5 NIC | 0.01 NIC/0.5 NIC | 0.05 NIC/0.5 NIC | |

| Mean ± SEM (s) | 440.40 ± 81.83 | 449.46 ± 79.64 | 502.99 ± 64.97 | 600.00 ± 0 | 456.92 ± 74.78 | 518.23 ± 55.36 |

| Mice to reach terminus | 30% | 30% | 20% | 0% | 27% | 15% |

P < 0.06 compared with VEH/VEH.

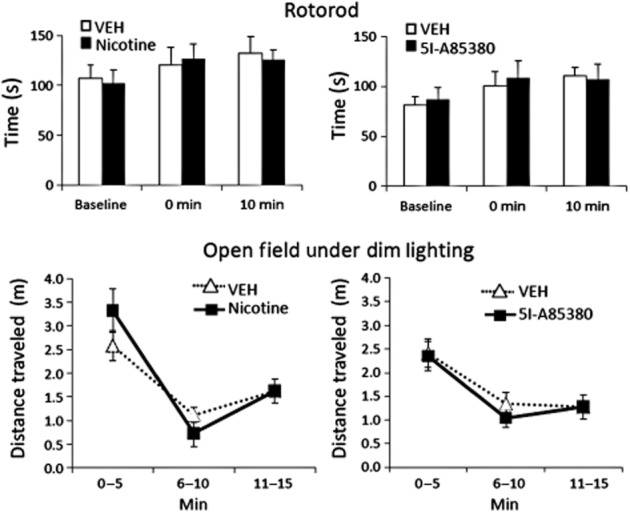

Experiments 7 and 8: rotorod and open-field assessment of high-dose nicotine and 5I-A85380

To clarify if reductions of movement in the light–dark and EPM assays were due to increased anxiety-state or disrupted locomotor function following 0.5 mg·kg−1 nicotine and 0.032 mg·kg−1 5I-A85380, mice were assessed in a rotorod test and in an open-field apparatus under low anxiety conditions. Neither nicotine (F2,18 = 0.319, P = 0.731) nor 5I-A85380 (F2,16 = 0.101, P = 0.836) resulted in changes from baseline rotorod performance as measured by time on the rotorod at 1 min and 10 min post-injection (Figure 7). Drug exposure also failed to affect the highest RPM achieved or distance traveled (P's > 0.1). Under low light conditions mice habituated to an open field as measured by reductions in distance travelled over 3 days of exposure (F1, 8 = 47.333, P < 0.001; F1, 9 = 46.850, P < 0.001). During subsequent 15 min training sessions mice showed reduced activity across 5 min timebins (F2, 16 = 24.926, P < 0.001; F2, 18 = 16.245, P < 0.001) that was independent of drug exposure. There was no interaction of time bin × drug treatment for distance travelled following nicotine (F2, 16 = 1.877, P = 0.185) or 5I-A85380 (F2, 18 = 0.15, P = 0.879) exposure and no main effect of drug exposure for either compound (P's > 0.1). Together these data support that high-dose nicotine- and 5I-A85380-associated reductions in exploration of the EPM and light–dark tasks were not due to gross behavioural disruption of these compounds, but rather appear to reflect increases in anxiety-like behaviour in these assays.

Figure 7.

High doses of nicotine and 5I-A85830 did not affect mouse rotorod performance or open-field horizontal activity under dim lighting. Mice tested at 0 and 10 min post-injection did not show any impairment in rotorod performance following i.p. injection of anxiogenic-like doses of 0.5 mg·kg−1 nicotine or 0.0032 mg·kg−1 of the β2*nAChR-selective agonist, 5I-A85380. Mice habituated to an open field also failed to show any effect of drug exposure on distance travelled under low-anxiety conditions. Data are reported as means ± SEM.

Discussion

The present experiments demonstrate that nicotine exerts both its anxiolytic-like and anxiogenic-like effects via β2*nAChRs, but that this is differentially accomplished by inhibition and stimulation, respectively, of β2*nAChRs. Ethological anxiety test procedures such as the EPM and light–dark assays assess the competing drives of rodents to explore their surroundings (i.e. venture into novel and open areas) and to avoid predation (i.e. limit movement and remain concealed). By design, mice favour the shielded areas of the EPM and light–dark apparatus, but FDA-approved anxiolytic drugs dose-dependently increase exploration and time spent in the open and exposed areas (Crawley and Goodwin, 1980; Griebel et al., 2000). The magnitude of anxiolytic-like effects of low-dose nicotine and 5I-A85380 in the present study is similar to previous reports for benzodiazepines in C57BL/6J mice (Griebel et al., 2000). Unlike benzodiazepines, dose-associated anxiolytic-like effects of these nicotinic compounds were not linear but rather promoted anxiogenic-like behaviour at higher doses, perhaps due to dual agonist and antagonist activity at the nAChRs. Similar to its dose-associated bimodal effects on anxiety-like behaviours (File et al., 1998; Picciotto et al., 2002; McGranahan et al., 2011; Anderson and Brunzell, 2012; Varani et al., 2012), nicotine activates and desensitizes β2*nAChRs in a concentration-dependent manner. In vitro studies demonstrate that micromolar concentrations of nicotine activate β2*nAChRs whereas pretreatment with nanomolar concentrations of nicotine can preferentially desensitize β2*nAChRs, rendering them unavailable for subsequent stimulation by ACh or nicotine (Lester and Dani, 1995; Fenster et al., 1997; Pidoplichko et al., 1997; Lu et al., 1999; Mansvelder et al., 2002; Kuryatov et al., 2011; Grady et al., 2012), but see Liu et al. (2012) on α6α4β2*nAChRs. Like the selective β2*nAChR antagonist, DHβE, the present studies similarly show that in vivo pre-administration of low-dose nicotine can attenuate the anxiogenic behavioural effects of a higher dose of nicotine. The fact that low-dose nicotine pretreatment did not accumulate with the high nicotine dose to increase anxiety-like behaviour, but rather blocked the anxiogenic-like effects of 0.5 mg·kg−1 nicotine suggests that low-dose nicotine pretreatment antagonizes nAChRs, which are critically involved in expression of this response. Low nicotine concentrations can also block the stimulatory effects of a nicotinic ganglionic agonist on mean arterial pressure (Buccafusco et al., 2007) and attenuate nicotine-induced release of prolactin (Sharp and Beyer, 1986; Hulihan-Giblin et al., 1990), further suggesting that low doses of systemic nicotine are capable of desensitizing nAChRs.

The selective β2*nAChR agonist 5I-A85380, like nicotine, showed similar bimodal anxiety effects, promoting anxiolysis-like behaviour at low doses in the EPM assay and promoting anxiogenic-like behaviour at the highest dose tested in light–dark and EPM assays. 5I-A85380, is 25 000× more selective for β2*nAChRs than other nAChR subtypes (Mukhin et al., 2000), suggesting that β2*nAChRs are sufficient to support bimodal anxiety-like behavioural effects. However, the observation that β2KO and WT mice spent similar time in the light chamber during the light–dark assay suggests that β2*nAChRs may not be necessary for expression of anxiolysis. The EPM and light–dark tasks have diverse molecular underpinnings revealed by genetic sensitivities (Griebel et al., 2000; Turri et al., 2004). Given the lack of effect of 5I-A85380 to promote anxiolysis in the light–dark assay, it is possible that the EPM and light–dark assay differentially depend upon β2*nAChRs to support anxiolysis under basal conditions. Like ACh and nicotine, sub-activating concentrations of 5I-A85380 also preferentially desensitize β2*nAChRs (Wageman et al., 2013). Therefore, it is possible that the anxiolytic-like effects of 5I-A85380 in the EPM were accomplished via inactivation of β2*nAChRs. Interestingly, we have previously observed leftward shifts for DHβE in the EPM compared with marble burying and conditioned emotional response assays (Anderson and Brunzell, 2012) to suggest that the EPM assay may rely to a larger extent on cholinergic tone at β2*nAChRs.

These findings are consistent with recent data showing that low-dose nicotine (0.01–0.05 mg·kg−1) and DHβE (0.3 and 3.0 kg−1) reverse conditioned inhibition and promote anxiolysis-like behaviour in mouse marble-burying and EPM tasks (McGranahan et al., 2011; Anderson and Brunzell, 2012), presumably via inhibition of ACh signalling in brain. The selective removal of cholinergic input to the basal lateral amygdala, where α4β2*nAChRs prevail, results in reduced anxiety-like behaviour (Power and McGaugh, 2002), supporting the role for inactivation of α4β2*nAChRs in the promotion of anxiolysis-like behaviours. α4β2*nAChRs also reside in the lateral septal nucleus where local infusion of 15 ng of mecamylamine, an nAChR antagonist, increased anxiolysis-like behaviour and blocked anxiogenic-like effects of nicotine (Ouagazzal et al., 1999b). Pharmacological findings were supported in part by genetic studies. β2KO mice showed attenuated latencies compared with WT mice following a high dose of nicotine, suggesting that activation of β2*nAChRs supports the anxiogenic-like effects of nicotine. Previous work suggests that the α4 subunit is required for nicotine-associated anxiolysis in the EPM assay, suggesting that α4β2*nAChRs regulate nicotine effects on anxiety behaviour (McGranahan et al., 2011), but because β2 subunits also assemble with α3 and α6 subunits, and all β2*nAChRs respond to β2*nAChR-selective agonist and antagonist compounds, the full complement of β2*nAChRs that regulate anxiety behaviour and their neuroanatomical location(s) remains to be determined.

As has been shown previously (Picciotto et al., 2002; McGranahan et al., 2011; Anderson and Brunzell, 2012), treatment with 0.05 mg·kg−1 nicotine resulted in anxiolytic-like behaviour, whereas 0.5 mg·kg−1 promoted anxiogenic-like behaviour of WT mice in the light–dark assay. Consistent with recent work using other anxiety models (Anderson and Brunzell, 2012), a 0.1 mg·kg−1 intermediate dose that supports nicotine CPP (Brunzell et al., 2009; Mineur et al., 2009) and which requires activation of β2*nAChRs (Walters et al., 2006) did not increase anxiolysis-like behaviour in the light–dark assay. This presumed stimulatory dose of nicotine also did not support anxiogenesis-like behaviour. That intermediate doses of nicotine promote reward-like behaviour and high doses support anxiogenesis is likely to be due to differences in neuroanatomical locale (Corrigall et al., 1994; Gould and Wehner, 1999; Power and McGaugh, 2002; Brunzell et al., 2010) as well as recruitment of nAChR subtypes other than β2*nAChRs (e.g. α3β4*nAChRs) at higher doses (Petersen et al., 1984; Fenster et al., 1997; Nelson and Lindstrom, 1999). The involvement of subtypes other than β2*nAChRs in this task is supported by the fact that an anxiogenic dose of nicotine blunted, but did not block, elevations in latency together with a lack of genotype effect for time spent in the light chamber. Of note, recent studies have observed nicotine CPP following 0.5 mg·kg−1 i.p. nicotine (Tang and Dani, 2009; Lee and Messing, 2011), suggesting that this higher dose of nicotine has mixed rewarding and anxiogenic-like effects.

β2KO mice in the present study showed partial attenuation of the anxiogenic-like effects of nicotine, suggesting that activation of other nAChRs, e.g. α3β4*nAChRs, contributed to behaviours observed following anxiogenic nicotine dosing. Early studies showed that β2KO mice expressed elevated passive avoidance learning (Picciotto et al., 1995), showing a net effect of enhanced learned anxiety-like behaviour following removal of the β2 subunit. Administration of the highest dose of 5I-A85380 resulted in increased time spent in the closed arms of an EPM without significantly affecting the number of entries made in the closed arms of the EPM, suggesting that selective activation of β2*nAChRs promotes anxiogenic-like behaviour without grossly affecting locomotor activity (but see Discussion later). High-dose nicotine that supports anxiogenic-like behaviour (File et al., 1998; Picciotto et al., 2002) can also reduce horizontal activity as was observed in the light–dark assay. Previous work shows that 0.5 mg·kg−1 i.p. nicotine significantly reduces activity in a novel environment, but not in the home cage (Salas et al., 2004; Tritto et al., 2004). Anxiogenic doses of nicotine and 5I-A85830 failed to affect rotorod activity or locomotor behaviour in a habituated open field under dimly lit conditions in the present studies, suggesting that reduced exploration in these assays was not due to non-specific behavioural disruption or sedation. Rather, reductions in exploration in the novel EPM and light–dark environments may reflect an elevated anxiety state of the mice following the high dose of nicotine and 5I-A85380. In the light–dark assay, both WT and β2KO mice showed reduced movement counts, suggesting that another nAChR subtype may support this behaviour. Mice lacking the β4 subunit (β4KO) are less sensitive to the locomotor-suppressive effects of 0.5 mg·kg−1 nicotine than WT mice and also show reduced anxiety-like behaviour in the EPM and staircase maze assays (Salas et al., 2003; 2004,). The β4 subunit primarily assembles with α3 and α3β4*nAChRs are enriched in the habenula, making these receptors neuroanatomically situated to promote anxiety and associated locomotor suppressant effects of nicotine (Quick et al., 1999).

It is possible that subclasses of β2*nAChRs may be particularly sensitive to the effects of high-dose nicotine. Mice with a deletion of the α4 subunit are less sensitive to the locomotor-suppressive effects of high-dose nicotine (Marubio et al., 2003) and administration of the β2*nAChR partial agonist, varenicline (Ortiz et al., 2012), blocks nicotine-induced suppression of locomotor activity. A high dose of 5I-A85380 reduced locomotor activity in the light–dark assay. Previous studies suggest that α4α6β2*nAChRs, which are more resistant to desensitization than α4β2*nAChRs (non-α6) (Liu et al., 2012), predominantly regulate the locomotor effects of nicotine (Drenan et al., 2010). DHβE pre-injection, which antagonizes α4β2*nAChR and α4α6β2*nAChRs also reversed ‘locomotor-suppressant’ effects of 0.5 mg·kg−1 nicotine in the present studies.

The effect of nicotine on anxiety in humans appears to depend upon many variables including predisposition for anxiety and smoking histories. Individuals with diagnosis of anxiety disorder are two times more likely to smoke than otherwise healthy smokers (Lasser et al., 2000). It is not known whether β2*nAChR expression correlates with anxiety-disorder diagnosis, but smokers, compared with non-smokers, show significant elevations in high-affinity β2*nAChR binding (Benwell et al., 1988; Breese et al., 1997; Cosgrove et al., 2009) and are more anxious overall than non-smokers (Tsuda et al., 1996; Gilbert et al., 2008). Compared with placebo, nicotine patches alleviated negative affect in smokers, but not non-smokers in a picture-attention task (Gilbert et al., 2008). Nicotine patches have been shown to reduce the functional connective strength between the amygdala with insular and anterior cingulate cortices in smokers, but to increase this connectivity in non-smokers (Sutherland et al., 2013). Similar reductions in the activation of amygdalar networks were observed in human smokers following pre-injection with the partial β2*nAChR agonist varenicline (Sutherland et al., 2013), implicating inhibition of β2*nAChRs in this neuroanatomical ‘re-wiring’. These findings are particularly germane considering that human-imaging studies show increased activity in both the amygdala and prefrontal cortex in subjects presenting with trait anxiety (Britton et al., 2011; Sehlmeyer et al., 2011) and provide a mechanistic explanation to the hypothesis that people suffering from anxiety-related disorders may be using cigarette smoking as a means of self-medication. For individuals who are motivated to smoke to relieve anxiety, it appears that low doses of nicotine may be sufficient to support nicotine intake. Despite self-reports from smokers, there is no clinical evidence to suggest that nicotine's anxiolytic effects are as potent as FDA-approved drugs, such as benzodiazepines and it is likely that nicotine alleviates anxiety in smokers, in part, via relief of withdrawal (Parrott, 1999). Nonetheless, these acute preclinical rodent studies provide physiological evidence to demonstrate that inhibition of β2*nAChRs is a possible mechanism by which smokers may experience relief of anxiety, leading to the maintenance of smoking behaviour. This is highly relevant to smokers given current policy measures being considered to reduce nicotine in cigarettes (Pearson et al., 2013) as even low doses of nicotine are capable of binding (and desensitizing) nearly 80% of β2*nAChRs in brain (Brody et al., 2009).

In conclusion, the light–dark and EPM assays are rodent models with good predictive validity for anxiolytic drug efficacy. These genetic and pharmacological data support that the anxiolytic-like effects of nicotine are regulated via inhibition of β2*nAChRs and suggest that β2*nAChR stimulation contributes to increased anxiety-like behaviour. These preclinical studies further demonstrate the efficacy of low doses of nicotine to prevent increases in anxiety-like behaviours resulting from activation of the cholinergic system with high doses of nicotine. Whereas the precise confirmation of nicotinic receptors regulating this behaviour remains to be determined, these preclinical studies indicate that partial agonists or negative allosteric modulators of β2*nAChRs may be helpful therapeutic strategies for the treatment of smoking cessation in smokers with anxiety-related co-morbidities.

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank J. M. Lee for technical assistance in mouse colony management and husbandry. We thank M. I. Damaj [National Institutes of Health (NIH) R01DA012610] and J.A. Stitzel (NIH P30DA016336) for providing β2 null mutant mice for experiment 1. S. M. Anderson was supported by NIH training grant T32DA7027 to W. L. Dewey. This work was supported by a Thomas F. and Kate Miller Jeffress Memorial Trust research grant J-951 and NIH R01DA031289 to D. H. Brunzell.

Glossary

- β2*nAChRs

β2 subunit containing nicotinic ACh receptors *denotes possible assembly with other subunits

- EPM

elevated plus maze

Authors contributions

S. M. A. carried out these experiments and D. H. B. supervised this work. Both authors contributed to the experimental design, statistical analysis and the writing of this study.

Conflict of interest

None.

Supporting Information

Additional Supporting Information may be found in the online version of this article at the publisher's web-site:

Table S1 Nicotine pre-injection time course.

References

- Alexander SP, Benson HE, Faccenda E, Pawson AJ, Sharman JL, Spedding M, et al. The concise guide to PHARMACOLOGY 2013/14: Ligand-gated ion channels. Br J Pharmacol. 2013;170:1582–1606. doi: 10.1111/bph.12446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson SM, Brunzell DH. Low dose nicotine and antagonism of beta2 subunit containing nicotinic acetylcholine receptors have similar effects on affective behavior in mice. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e48665. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0048665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benwell ME, Balfour DJ, Anderson JM. Evidence that tobacco smoking increases the density of (−)-[3H]nicotine binding sites in human brain. J Neurochem. 1988;50:1243–1247. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1988.tb10600.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breese CR, Marks MJ, Logel J, Adams CE, Sullivan B, Collins AC, et al. Effect of smoking history on [3H]nicotine binding in human postmortem brain. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1997;282:7–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Britton JC, Lissek S, Grillon C, Norcross MA, Pine DS. Development of anxiety: the role of threat appraisal and fear learning. Depress Anxiety. 2011;28:5–17. doi: 10.1002/da.20733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brody AL, Mandelkern MA, Costello MR, Abrams AL, Scheibal D, Farahi J, et al. Brain nicotinic acetylcholine receptor occupancy: effect of smoking a denicotinized cigarette. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2009;12:305–316. doi: 10.1017/S146114570800922X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunzell DH, Mineur YS, Neve RL, Picciotto MR. Nucleus accumbens CREB activity is necessary for nicotine conditioned place preference. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2009;34:1993–2001. doi: 10.1038/npp.2009.11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunzell DH, Boschen KE, Hendrick ES, Beardsley PM, McIntosh JM. Alpha-conotoxin MII-sensitive nicotinic acetylcholine receptors in the nucleus accumbens shell regulate progressive ratio responding maintained by nicotine. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2010;35:665–673. doi: 10.1038/npp.2009.171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buccafusco JJ, Shuster LC, Terry AV., Jr Disconnection between activation and desensitization of autonomic nicotinic receptors by nicotine and cotinine. Neurosci Lett. 2007;413:68–71. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2006.11.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheeta S, Tucci S, File SE. Antagonism of the anxiolytic effect of nicotine in the dorsal raphe nucleus by dihydro-beta-erythroidine. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2001;70:491–496. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(01)00641-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corrigall WA, Coen KM, Adamson KL. Self-administered nicotine activates the mesolimbic dopamine system through the ventral tegmental area. Brain Res. 1994;653:278–284. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(94)90401-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cosgrove KP, Batis J, Bois F, Maciejewski PK, Esterlis I, Kloczynski T, et al. beta2-Nicotinic acetylcholine receptor availability during acute and prolonged abstinence from tobacco smoking. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2009;66:666–676. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2009.41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crawley J, Goodwin FK. Preliminary report of a simple animal behavior model for the anxiolytic effects of benzodiazepines. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1980;13:167–170. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(80)90067-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalvi A, Rodgers RJ. GABAergic influences on plus-maze behaviour in mice. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1996;128:380–397. doi: 10.1007/s002130050148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drenan RM, Grady SR, Steele AD, McKinney S, Patzlaff NE, McIntosh JM, et al. Cholinergic modulation of locomotion and striatal dopamine release is mediated by alpha6alpha4* nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. J Neurosci. 2010;30:9877–9889. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2056-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evatt DP, Kassel JD. Smoking, arousal, and affect: the role of anxiety sensitivity. J Anxiety Disord. 2010;24:114–123. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2009.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fenster CP, Rains MF, Noerager B, Quick MW, Lester RA. Influence of subunit composition on desensitization of neuronal acetylcholine receptors at low concentrations of nicotine. J Neurosci. 1997;17:5747–5759. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-15-05747.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fidler JA, West R. Self-perceived smoking motives and their correlates in a general population sample. Nicotine Tob Res. 2009;11:1182–1188. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntp120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- File SE, Kenny PJ, Ouagazzal AM. Bimodal modulation by nicotine of anxiety in the social interaction test: role of the dorsal hippocampus. Behav Neurosci. 1998;112:1423–1429. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.112.6.1423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert DG, Rabinovich NE, Malpass D, Mrnak J, Riise H, Adams L, et al. Effects of nicotine on affect are moderated by stressor proximity and frequency, positive alternatives, and smoker status. Nicotine Tob Res. 2008;10:1171–1183. doi: 10.1080/14622200802163092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gould TJ, Wehner JM. Nicotine enhancement of contextual fear conditioning. Behav Brain Res. 1999;102:31–39. doi: 10.1016/s0166-4328(98)00157-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grady SR, Wageman CR, Patzlaff NE, Marks MJ. Low concentrations of nicotine differentially desensitize nicotinic acetylcholine receptors that include alpha5 or alpha6 subunits and that mediate synaptosomal neurotransmitter release. Neuropharmacology. 2012;62:1935–1943. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2011.12.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griebel G, Belzung C, Perrault G, Sanger DJ. Differences in anxiety-related behaviors and in sensitivity to diazepam in inbred and outbred strains of mice. Psychopharmacology. 2000;148:164–170. doi: 10.1007/s002130050038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grillon C, Avenevoli S, Daurignac E, Merikangas KR. Fear-potentiated startle to threat, and prepulse inhibition among young adult nonsmokers, abstinent smokers, and nonabstinent smokers. Biol Psychiatry. 2007;62:1155–1161. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.12.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hulihan-Giblin BA, Lumpkin MD, Kellar KJ. Acute effects of nicotine on prolactin release in the rat: agonist and antagonist effects of a single injection of nicotine. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1990;252:15–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hussmann GP, DeDominicis KE, Turner JR, Yasuda RP, Klehm J, Forcelli PA, et al. Chronic sazetidine-A maintains anxiolytic effects and slower weight gain following chronic nicotine without maintaining increased density of nicotinic receptors in rodent brain. J Neurochem. 2014;129:721–731. doi: 10.1111/jnc.12653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilkenny C, Browne W, Cuthill IC, Emerson M, Altman DG. Animal research: reporting in vivo experiments: the ARRIVE guidelines. Br J Pharmacol. 2010;160:1577–1579. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2010.00872.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuryatov A, Berrettini W, Lindstrom J. Acetylcholine receptor (AChR) alpha5 subunit variant associated with risk for nicotine dependence and lung cancer reduces (alpha4beta2)alpha5 AChR function. Mol Pharmacol. 2011;79:119–125. doi: 10.1124/mol.110.066357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lasser K, Boyd JW, Woolhandler S, Himmelstein DU, McCormick D, Bor DH. Smoking and mental illness: a population-based prevalence study. JAMA. 2000;284:2606–2610. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.20.2606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee AM, Messing RO. Protein kinase C epsilon modulates nicotine consumption and dopamine reward signals in the nucleus accumbens. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:16080–16085. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1106277108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lester RA, Dani JA. Acetylcholine receptor desensitization induced by nicotine in rat medial habenula neurons. J Neurophysiol. 1995;74:195–206. doi: 10.1152/jn.1995.74.1.195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu L, Zhao-Shea R, McIntosh JM, Gardner PD, Tapper AR. Nicotine persistently activates ventral tegmental area dopaminergic neurons via nicotinic acetylcholine receptors containing alpha4 and alpha6 subunits. Mol Pharmacol. 2012;81:541–548. doi: 10.1124/mol.111.076661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu Y, Marks MJ, Collins AC. Desensitization of nicotinic agonist-induced [3H]gamma-aminobutyric acid release from mouse brain synaptosomes is produced by subactivating concentrations of agonists. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1999;291:1127–1134. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mansvelder HD, Keath JR, McGehee DS. Synaptic mechanisms underlie nicotine-induced excitability of brain reward areas. Neuron. 2002;33:905–919. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00625-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marubio LM, Gardier AM, Durier S, David D, Klink R, Arroyo-Jimenez MM, et al. Effects of nicotine in the dopaminergic system of mice lacking the alpha4 subunit of neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. Eur J Neurosci. 2003;17:1329–1337. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2003.02564.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGranahan TM, Patzlaff NE, Grady SR, Heinemann SF, Booker TK. alpha4beta2 nicotinic acetylcholine receptors on dopaminergic neurons mediate nicotine reward and anxiety relief. J Neurosci. 2011;31:10891–10902. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0937-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGrath J, Drummond G, McLachlan E, Kilkenny C, Wainwright C. Guidelines for reporting experiments involving animals: the ARRIVE guidelines. Br J Pharmacol. 2010;160:1573–1576. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2010.00873.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mineur YS, Brunzell DH, Grady SR, Lindstrom JM, McIntosh JM, Marks MJ, et al. Localized low-level re-expression of high-affinity mesolimbic nicotinic acetylcholine receptors restores nicotine-induced locomotion but not place conditioning. Genes Brain Behav. 2009;8:257–266. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-183X.2008.00468.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukhin AG, Gundisch D, Horti AG, Koren AO, Tamagnan G, Kimes AS, et al. 5-Iodo-A-85380, an alpha4beta2 subtype-selective ligand for nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. Mol Pharmacol. 2000;57:642–649. doi: 10.1124/mol.57.3.642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson ME, Lindstrom J. Single channel properties of human alpha3 AChRs: impact of beta2, beta4 and alpha5 subunits. J Physiol. 1999;516(Pt 3):657–678. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1999.0657u.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ortiz NC, O'neill HC, Marks MJ, Grady SR. Varenicline blocks beta2*-nAChR-mediated response and activates beta4*-nAChR-mediated responses in mice in vivo. Nicotine Tob Res. 2012;14:711–719. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntr284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ouagazzal AM, Kenny PJ, File SE. Modulation of behaviour on trials 1 and 2 in the elevated plus-maze test of anxiety after systemic and hippocampal administration of nicotine. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1999a;144:54–60. doi: 10.1007/s002130050976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ouagazzal AM, Kenny PJ, File SE. Stimulation of nicotinic receptors in the lateral septal nucleus increases anxiety. Eur J Neurosci. 1999b;11:3957–3962. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.1999.00823.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parrott AC. Does cigarette smoking cause stress? Am Psychol. 1999;54:817–820. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.54.10.817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pawson AJ, Sharman JL, Benson HE, Faccenda E, Alexander SP, Buneman OP, et al. NC-IUPHAR. The IUPHAR/BPS Guide to PHARMACOLOGY: an expert-driven knowledge base of drug targets and their ligands. Nucl Acids Res. 2014;42(Database Issue):D1098–D1106. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt1143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearson JL, Abrams DB, Niaura RS, Richardson A, Vallone DM. Public support for mandated nicotine reduction in cigarettes. Am J Public Health. 2013;103:562–567. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.300890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perkins KA, Grobe JE. Increased desire to smoke during acute stress. Br J Addict. 1992;87:1037–1040. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1992.tb03121.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersen DR, Norris KJ, Thompson JA. A comparative study of the disposition of nicotine and its metabolites in three inbred strains of mice. Drug Metab Dispos. 1984;12:725–731. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Picciotto MR, Zoli M, Lena C, Bessis A, Lallemand Y, Le Novere N, et al. Abnormal avoidance learning in mice lacking functional high-affinity nicotine receptor in the brain. Nature. 1995;374:65–67. doi: 10.1038/374065a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Picciotto MR, Brunzell DH, Caldarone BJ. Effect of nicotine and nicotinic receptors on anxiety and depression. Neuroreport. 2002;13:1097–1106. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200207020-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pidoplichko VI, Debiasi M, Williams JT, Dani JA. Nicotine activates and desensitizes midbrain dopamine neurons. Nature. 1997;390:401–404. doi: 10.1038/37120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Power AE, McGaugh JL. Cholinergic activation of the basolateral amygdala regulates unlearned freezing behavior in rats. Behav Brain Res. 2002;134:307–315. doi: 10.1016/s0166-4328(02)00046-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quick MW, Ceballos RM, Kasten M, McIntosh JM, Lester RA. Alpha3beta4 subunit-containing nicotinic receptors dominate function in rat medial habenula neurons. Neuropharmacology. 1999;38:769–783. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(99)00024-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salas R, Fredaline P, Beryl F, Dani JA, De Biasi M. Altered anxiety-related responses in mutant mice lacking the β4 subunit of the nicotinic receptor. J Neurosci. 2003;23:6255–6263. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-15-06255.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salas R, Cook KD, Bassetto L, De Biasi M. The α3 and β4 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor subunits are necessary for nicotine-induced seizures and hypolocomotion in mice. Neuropharmacology. 2004;47:401–407. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2004.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salminen O, Murphy KL, McIntosh JM, Drago J, Marks MJ, Collins AC, et al. Subunit composition and pharmacology of two classes of striatal presynaptic nicotinic acetylcholine receptors mediating dopamine release in mice. Mol Pharmacol. 2004;65:1526–1535. doi: 10.1124/mol.65.6.1526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sehlmeyer C, Dannlowski U, Schoning S, Kugel H, Pyka M, Pfleiderer B, et al. Neural correlates of trait anxiety in fear extinction. Psychol Med. 2011;41:789–798. doi: 10.1017/S0033291710001248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharp BM, Beyer HS. Rapid desensitization of the acute stimulatory effects of nicotine on rat plasma adrenocorticotropin and prolactin. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1986;238:486–491. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiffman S, Hickcox M, Paty JA, Gnys M, Richards T, Kassel JD. Individual differences in the context of smoking lapse episodes. Addict Behav. 1997;22:797–811. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(97)00063-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skara S, Sussman S, Dent CW. Predicting regular cigarette use among continuation high school students. Am J Health Behav. 2001;25:147–156. doi: 10.5993/ajhb.25.2.7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutherland MT, Carroll AJ, Salmeron BJ, Ross TJ, Hong LE, Stein EA. Down-regulation of amygdala and insula functional circuits by varenicline and nicotine in abstinent cigarette smokers. Biol Psychiatry. 2013;74:538–546. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2013.01.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang J, Dani JA. Dopamine enables in vivo synaptic plasticity associated with the addictive drug nicotine. Neuron. 2009;63:673–682. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2009.07.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tritto T, McCallum SE, Waddle SA, Hutton SR, Paylor R, Collins AC, et al. Null mutant analysis of responses to nicotine: deletion of beta2 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor subunit but not alpha7 subunit reduces sensitivity to nicotine-induced locomotor depression and hypothermia. Nicotine Tob Res. 2004;6:145–158. doi: 10.1080/14622200310001656966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsuda A, Steptoe A, West R, Fieldman G, Kirschbaum C. Cigarette smoking and psychophysiological stress responsiveness: effects of recent smoking and temporary abstinence. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1996;126:226–233. doi: 10.1007/BF02246452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner JR, Castellano LM, Blendy JA. Nicotinic partial agonists varenicline and sazetidine-A have differential effects on affective behavior. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2010;334:665–672. doi: 10.1124/jpet.110.166280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turri MG, DeFries JC, Henderson ND, Flint J. Multivariate analysis of quantitative trait loci influencing variation in anxiety-related behavior in laboratory mice. Mamm Genome. 2004;15:69–76. doi: 10.1007/s00335-003-3032-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varani AP, Moutinho LM, Bettler B, Balerio GN. Acute behavioural responses to nicotine and nicotine withdrawal syndrome are modified in GABA(B1) knockout mice. Neuropharmacology. 2012;63:863–872. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2012.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wageman CR, Marks MJ, Grady SR. Effectiveness of nicotinic agonists as desensitizers at presynaptic alpha4beta2- and alpha4alpha5beta2-nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. Nicotine Tob Res. 2013;16:207–305. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntt146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walters CL, Brown S, Changeux JP, Martin B, Damaj MI. The beta2 but not alpha7 subunit of the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor is required for nicotine-conditioned place preference in mice. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2006;184:339–344. doi: 10.1007/s00213-005-0295-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiley JL, Cristello AF, Balster RL. Effects of site-selective NMDA receptor antagonists in an elevated plus-maze model of anxiety in mice. Eur J Pharmacol. 1995;294:101–107. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(95)00506-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zarrindast MR, Solati J, Oryan S, Parivar K. Effect of intra-amygdala injection of nicotine and GABA receptor agents on anxiety-like behaviour in rats. Pharmacology. 2008;82:276–284. doi: 10.1159/000161129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1 Nicotine pre-injection time course.