Abstract

Postovulatory aging is associated with several morphological, cellular and molecular changes that deteriorate egg quality either by inducing abortive spontaneous egg activation (SEA) or by egg apoptosis. The reduced egg quality results in poor fertilization rate, embryo quality and reproductive outcome. Although postovulatory aging-induced abortive SEA has been reported in several mammalian species, the molecular mechanism(s) underlying this process remains to be elucidated. The postovulatory aging-induced morphological and cellular changes are characterized by partial cortical granules exocytosis, zona pellucida hardening, exit from metaphase-II (M-II)arrest and initiation of extrusion of second polar body in aged eggs. The molecular changes include reduction of adenosine 3',5'- cyclic monophosphate (cAMP) level, increase of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and thereby cytosolic free calcium (Ca2+) level. Increased levels of cAMP and/or ROS trigger accumulation of Thr-14/Tyr-15 phosphorylated cyclin-dependent kinase 1 (Cdk1) on one hand and degradation of cyclin B1 through ubiquitin-mediated proteolysis on the other hand to destabilize maturation promoting factor (MPF). The destabilized MPF triggers postovulatory aging-induced abortive SEA and limits various assisted reproductive technologies (ARTs) outcome in several mammalian species. Use of certain drugs that can either increase cAMP or reduce ROS level would prevent postovulatory aging-induced deterioration in egg quality so that more number of good quality eggs can be made available to improve ART outcome in mammals including human.

Keywords: Postovulatory aging, Abortive SEA, Signal molecules, MPF, ART, Mammals

Introduction

In mammals, freshly ovulated eggs are arrested at metaphase-II (M-II) stage of meiotic cell cycle and possess first polar body (PB-I) with normal morphology [1-3]. If fertilization does not occur within the window period soon after ovulation, unfertilized eggs remaining in the oviduct or under in vitro culture conditions, undergo time-dependent deterioration in quality by a process called postovulatory egg aging [4,5]. Postovulatory aging induces exit from M-II arrest and initiation of second polar body (PB-II) extrusion [2]. The chromosomes are scattered in the cytoplasm and aged eggs are further arrested at metaphase-III (M-III) like stage without forming pronuclei [2]. The initiation of extrusion of PB-II occurs soon after ovulation and large amount of cytoplasm move towards PB-II area but it never gets completely extruded. This atypical condition is called spontaneous egg activation (SEA) [2].

The SEA was reported in rat for the first time by Keefer and Schuetz in 1982 [6] and later by several research groups [2,5,7-11]. This pathological condition has also been observed in several mammalian species such as mice [12,13], porcine [14-16], bovine [17], hamster [18] and human eggs [19-21]. The percentage of eggs undergoing SEA varies from species to species in mammals. Ross et al. (2006) observed that approximately 35 % to 85 % of ovulated eggs undergo SEA in different strains of rat. Studies from our laboratory suggest that the postovulatory egg aging results SEA in 90 % of ovulated eggs in vivo as well as in vitro [2,3,8,9]. In human, egg aging is one of the problems associated with ART failure [4]. Therefore, improvements of egg quality through methodological advances are in critical demand to prevent egg aging process during ART procedure [4]. Aged eggs limits the ART outcome, hence the establishment of method(s) to prevent egg aging could enhance progress in ART technologies and their outcome [4]. Based on our recent findings, we propose that the postovulatory aging-induced abortive SEA could be due to changes in the level of signal molecules and their effect on maturation promoting factor (MPF) because the high level of MPF heterodimer and cytostatic factors (CSF) activity are required for maintenance of M-II arrest in freshly ovulated eggs [22,23]. The postovulatory aging reduces egg quality by inducing apoptosis that finally affect reproductive outcome [2,3,24-29].

Review

Morphological changes during postovulatory egg aging

Normally egg activation is triggered by fertilizing spermatozoa and it is morphologically characterized by cortical granule exocytosis, pronuclei formation and complete extrusion of PB-II in mammal [2,12,30]. In the absence of fertilization, in several mammalian species, postovulatory aging induces SEA both in vivo as well as in vitro, which mimics the morphological features characteristics of egg activation [2,6,7,19,31,32]. In rat, postovulatory aging induces incomplete extrusion of PB-II without forming pronuclei and eggs are arrested at M-III like stage so called abortive SEA (Fig.1) [2]. The large amount of egg cytoplasm moves towards PB-II and it is not cytoplasmic division, which results partial extrusion of PB-II. The incomplete extrusion of PB-II generates a pathological condition because these eggs cannot be used for assisted reproductive technology (ART) program [2]. The postovulatory aging triggers degeneration of PB-I, increases perivitelline space (PVS) and partial cortical granule exocytosis [4]. Due to energy depletion, postovulatory aging generates ROS and thereby egg apoptosis [28,33]. The egg apoptosis has been morphologically characterized by shrinkage, membrane blebbing, cytoplasmic fragmentation, cytoplasmic granulation and degeneration [1,9-11,28,33-38].

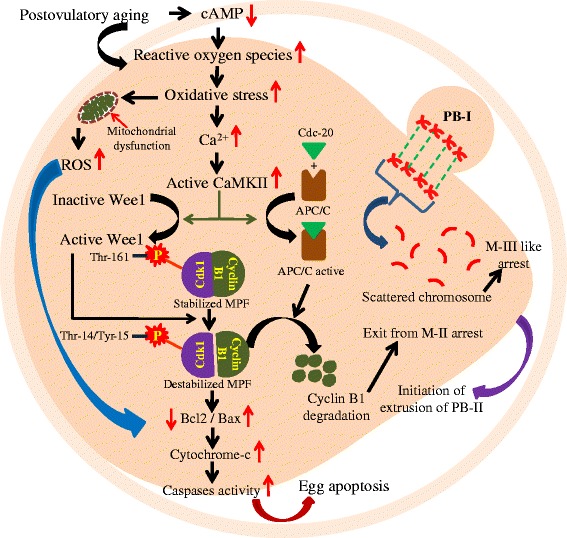

Fig. 1.

A schematic diagram showing the molecular changes associated with postovulatory aging-induced abortive SEA. Postovulatory egg aging reduces cAMP and/or induces generation of ROS that results in oxidative stress. The oxidative stress impairs mitochondrial membrane potential and increases cytosolic free Ca2+ level. The increased cytosolic free Ca2+ level results in the activation of Wee1 and APC/C. Wee1 modulates Cdk1 phosphorylation and destabilizes MPF heterodimer. The active APC/C triggers cyclin B1 degradation through ubiquitin-mediated proteolysis. The destabilized MPF triggers an exit from M-II arrest but chromosomes are scattered in the cytoplasm and pronuclei is not formed. The increased level of ROS and/or sustained destabilized MPF may trigger proapoptotic as well as apoptotic factors leading to apoptosis in aged eggs. Increased cAMP level and decreased Ca 2+ and ROS levels using specific drugs could be beneficial to prevent postovulatory aging-induced deterioration of egg quality

Cellular changes during postovulatory egg aging

Postovulatory aging causes tight aggregations of granulofibrillar material and zona pellucida hardening in eggs [4,12,39,40]. Thick microfilament domain underlying the plasma membrane is either disrupted or lost [41]. Number of lysosomes is increased and tubuli from smooth endoplasmic reticulum and small mitochondriacomplexes are aggregated in aged eggs [4,42]. Cortical granules are displaced and undergo partial exocytosis [4,12,39,40]. The mitochondria membrane potential is decreased, which results in the swelling of matrix [43]. Length of spindle is reduced leading to severe consequences for chromosome segregation. The centrosome structure, microtubule integrity and maintenance of chromosome at metaphase plate are lost [4,44,45]. As a result, pronuclei is not formed during postovulatory aging-induced abortive SEA (Fig. 1). Further, postovulatory aging triggers premature chromosome separation, chromosomal dispersion and decondensation, clumping of chromosome and chromatid separation in eggs [4,46,47] that could lead to epigenetic changes in offspring [23,48].

Molecular changes during postovulatory egg aging

The depletion of ATP reserve and thereby adenosine 3',5'- cyclic monophosphate (cAMP) that leads to generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) in aged eggs [33,37,38]. The decrease of intracellular cAMP in aging eggs is one of the important signals that initiates an exit from M-II arrest [2,49]. Few studies suggest that reduced cAMP level is associated with an increase of hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) in aged eggs cultured in vitro [50,51]. The lack of antioxidants and increased oxygen tension are other important factors that triggers the generation of ROS [13,23,52,53].

Increased oxidative stress due to generation of ROS causes dysfunction and shrinkage of mitochondria [23,38] that reduces mitochondrial membrane potential in aging eggs [53,54]. This is further supported by our observations that exogenous supplementation of dibutyryl cAMP (db-cAMP) or non-enzymatic antioxidant prevents postovulatory aging-induced abortive SEA [1-3]. Oxidative stress induces expression of proapoptotic factors (Bax and cytochrome c) and apoptotic factors (caspase-3 and DNA fragmentation) and thereby apoptosis in aged eggs cultured in vitro [9,55]. The increased level of H2O2 reduces Bcl2 expression [56], increases Bax expression [9,34,38], cytochrome c level, caspases activities [28,33,38,55] and DNA fragmentation in rat eggs cultured in vitro [9].

Postovulatory aging-induced oxidative stress can modulate RyR channels of endoplasmic reticulum and increase cytosolic free calcium Ca2+ level [3]. This is further strengthened by our recent studies that ruthenium red, a specific RyR channel blocker reduces cytosolic free Ca2+ level and inhibits postovulatory aging-induced abortive SEA [3]. Further, increased H2O2 level associates with high cytosolic free Ca2+ level during postovulatory-induced abortive SEA [1-3,10,36,38]. The increased intracellular Ca2+ activates CaM-dependent kinase-II (CaMKII) [3,57,58] and KN93, a specific CaMKII inhibitor prevents postovulatory aging-induced abortive SEA [57,58]. On the other hand, due to high sustained level of Ca2+ in the cytoplasm, Ca2+ enters in the mitochondria and triggers generation of ROS, mitochondrial DNA damage and apoptosis in aged eggs cultured in vitro (Fig. 1) [2,38,59,60].

The CaMK-II activates anaphase promoting complex/cyclosome (APC/C) by releasing endogenous meiotic inhibitor 2 (Emi2; a CSF) as well as Wee 1, a tyrosine kinase [61,62]. Previous study suggests that increased level of ROS can also stimulate tyrosine kinase [63]. The active Wee 1 destabilizes MPF by inducing phosphorylation of Thr-14/Tyr-15 of Cdk1 (a catalytic unit of MPF) and triggers dissociation of cyclin B1 (a regulatory subunit of MPF) from MPF heterodimer [61,62,64]. The active APC/C induces degradation of cyclin B1 through ubiquitin-mediated proteolysis [61]. The destabilized MPF finally triggers an exit from M-II arrest and thereby initiation of extrusion of PB-II in aged eggs [40]. The postovulatory aging-induced MPF destabilization can be prevented using several drugs that can elevate cAMP level or reduce ROS level [2,23,65,66]. Other drugs like demecolcine, nocodazole, cytochalasin (B and D) and Na+/Ca2+ exchanger of plasma membrane prevent postovulatory aging-induced abortive SEA in rat oocytes [67-69]. Although, postovulatory aging induces initiation of extrusion of PB-II but it never gets completely extruded and chromosomes remain scattered in egg cytoplasm without forming pronuclei [2]. The reduced level of destabilized MPF and ATP depletion in aged egg result in increased expression of proapoptotic factors [26,70,71]. Overexpression of proapoptotic factors activate upstream as well as downstream caspases [13,72] that deteriorates egg quality by inducing apoptosis [26,73-75]. Indeed, postovulatory aging-induced deterioration of egg quality could be one of the limiting factors for poor in vitro fertilization rate in several mammalian species including human.

Conclusions

Postovulatory aging-induced abortive SEA is a pathological condition in mammals that limits ART outcome. Generation of ROS results in oxidative stress that increases cytosolic free Ca2+level. Aged eggs are unable to sustained high level of Ca2+, which leads to MPF destabilization. The destabilized MPF triggers exit from M-II arrest, a characteristic feature of abortive SEA (Fig. 1). In aged eggs, chromosomes are scattered in the egg cytoplasm and pronuclei is not formed. The increased oxidative stress and/or destabilized MPF deteriorate egg quality by inducing apoptosis. Although growing body of evidences suggest the possible players and pathways during postovulatory egg aging, further, studies are required to prevent aging process so that the good quality eggs are made available for various ART programs including somatic cell nuclear transfer during animal cloning.

Acknowledgement

The part of this study was funded by Department of Biotechnology, Ministry of Science and Technology, Government of India.

Abbreviations

- ART

Assisted reproductive technology

- APC/C

Anaphase promoting complex/cyclosome

- cAMP

Adenosine 3',5'- cyclic monophosphate

- Ca2+

Calcium

- CaMKII

CaM-dependent kinase-II

- Cdk1

Cyclin-dependent kinase 1

- CSF

Cytostatic factor

- db-cAMP

Dibutyryl cAMP

- Emi2

Endogenous meiotic inhibitor 2

- H2O2

Hydrogen peroxide

- M-II

Metaphase-II

- M-III

Metaphase-III

- MPF

Maturation promoting factor

- PB-I

Polar body-I

- PB-II

polar body-II

- PVS

perivitelline space

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

- SEA

spontaneous egg activation

Footnotes

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

SP and MT searched the literature and wrote the initial draft of manuscript. BK and SKC suggested the structure, revised and finished the final version of manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Contributor Information

Shilpa Prasad, Email: shilpaprasadskc@gmail.com.

Meenakshi Tiwari, Email: meenakshitiwariskc@gmail.com.

Biplob Koch, Email: kochbiplob@gmail.com.

Shail K. Chaube, Phone: 91-542-26702516, FAX: 91-542-2368174, Email: shailchaubey@gmail.com

References

- 1.Tripathi A, Prem Kumar KV, Chaube SK. Meiotic cell cycle arrest in mammalian oocytes. J Cell Physiol. 2010;223:592–600. doi: 10.1002/jcp.22108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Premkumar KV, Chaube SK. An insufficient increase of cytosolic free calcium level results postovulatory aging-induced abortive spontaneous egg activation in rat. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2013;30:117–23. doi: 10.1007/s10815-012-9908-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Premkumar KV, Chaube SK. RyR channel-mediated increase of cytosolic free calcium level signals cyclin B1 degradation during abortive spontaneous egg activation in rat. In Vitro Cell Dev Biol-Anim. 2014;50:640–7. doi: 10.1007/s11626-014-9749-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Miao YL, Kikuchi K, Sun QY, Schatten H. Oocyte aging: cellular and molecular changes, developmental potential and reversal possibility. Hum Reprod Update. 2009;15:573–85. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmp014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chebotareva T, Taylor J, Mullins JJ, Wilmut I. Rat eggs cannot wait: spontaneous exit from meiotic metaphase-II arrest. Mol Reprod Dev. 2011;78:795–807. doi: 10.1002/mrd.21385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Keefer CL, Schuetz AW. Spontaneous activation of ovulated rat oocytes during in vitro culture. J Exp Zool. 1982;224:371–7. doi: 10.1002/jez.1402240310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zernika-Goetz M. Spontaneous and induced activation of rat oocytes. Mol Reprod Dev. 1991;28:169–76. doi: 10.1002/mrd.1080280210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ross PJ, Yabuuchi A, Cibelli JB. Oocyte spontaneous activation in different rat strains. Cloning Stem Cells. 2006;8:275–82. doi: 10.1089/clo.2006.8.275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chaube SK, Dubey PK, Mishra SK, Shrivastav TG. Verapamil reversibly inhibits spontaneous parthenogenetic activation in aged rat eggs cultured in vitro. Cloning Stem Cells. 2007;9:608–17. doi: 10.1089/clo.2007.0001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chaube SK, Khatun S, Misra SK, Shrivastav TG. Calcium ionophore-induced egg activation and apoptosis with the generation of intracellular hydrogen peroxide. Free Rad Res. 2007;42:212–20. doi: 10.1080/10715760701868352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tripathi A, Khatun S, Pandey AN, Misra SK, Chaube R, Shrivastava TG, et al. Intracellular levels of hydrogen peroxide and nitric oxide in oocyte at various stages of meiotic cell cycle and apoptosis. Free Rad Res. 2009;43:287–94. doi: 10.1080/10715760802695985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Xu Z, Abbott A, Kopf GS, Schultz RM, Ducibella T. Spontaneous activation of ovulated mouse eggs: time-dependent effects on M-phase exit, cortical granule exocytosis, maternal messenger ribonucleic acid recruitment, and Inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate sensitivity. Biol Reprod. 1997;57:743–50. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod57.4.743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lord T, Nixon B, Jones KT, Aitken RJ. Melatonin prevents postovulatory oocyte aging in the mouse and extends the window for optimal fertilization in vitro. Biol Reprod. 2013;88:1–9. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.112.106450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ruddock NT, Machaty Z, Cabot RA, Prather RS. Porcine oocyte activation: roles of calcium and pH. Mol Reprod Dev. 2001;59:227–34. doi: 10.1002/mrd.1027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ito J, Shimada M, Terada T. Effect of protein kinase C inhibitor on mitogen-activated protein kinase and p34cdc2 kinase activity during parthenogenetic activation of porcine oocytes by calcium ionophore. Biol Reprod. 2003;69:1675–82. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.103.018036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ito J, Shimada M, Terada T. Mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase inhibitor suppresses cyclin B1 synthesis and reactivation of p34cdc2 kinase, which improves pronuclear formation rate in matured porcine oocytes activated by Ca2+ ionophore. Biol Reprod. 2004;70:797–804. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.103.020610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sergeev IN, Norman AV. Calcium as a mediator of apoptosis in bovine oocytes and preimplantation embryos. Endocrine. 2003;22:169–76. doi: 10.1385/ENDO:22:2:169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Juetten J, Bavister BD. Effects of egg aging on in vitro fertilization and first cleavage division in the hamster. Gamete Res. 1983;8:219–30. doi: 10.1002/mrd.1120080303. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lu Q, Chen ZJ, Gao X, Ma SY, Li M, Hu JM, et al. Oocyte activation with calcium ionophore A23187 and puromycin on human oocytes that failed to fertilize after intracytoplasmic sperm injection. Zhonghua Fu Chan Ke Za Zhi. 2006;41:182–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Escrich L, Grau N, Mercader A, Rubio C, Pellicer A, Escriba MJ. Spontaneous in vitro maturation and artificial activation of human germinal vesicle oocytes recovered from stimulated cycles. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2011;28:111–7. doi: 10.1007/s10815-010-9493-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Combelles CMH, Kearns WG, Fox JH, Racowsky C. Cellular and genetic analysis of oocytes and embryo in a case of spontaneous oocyte activation. Hum Reprod. 2011;26:545–52. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deq363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Madgwick S, Jones KT. How eggs arrest at metaphase II: MPF stabilization plus APC/C inhibition equals cytostatic factor. Cell Div. 2007;2:4–11. doi: 10.1186/1747-1028-2-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lord T, Aitken RJ. Oxidative stress and ageing of the post-ovulatory oocyte. Reproduction. 2013;146:R217–27. doi: 10.1530/REP-13-0111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wilcox AJ, Weinberg CR, Baird DD. Post-ovulatory ageing of the human oocyte and embryo failure. Hum Reprod. 1998;13:394–7. doi: 10.1093/humrep/13.2.394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tarin JJ, Pérez-Albalá S, Aguilar A, Miñarro J, Hermenegildo C, Cano A. Long-term effects of postovulatory aging of mouse oocytes on offspring: a two-generational study. Biol Reprod. 1999;61:1347–55. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod61.5.1347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gordo AC, Rodrigues P, Kurokawa M, Jellerette T, Exley GE, Warner C, et al. Intracellular calcium oscillations signal apoptosis rather than activation in in vitro aged mouse eggs. Biol Reprod. 2002;66:1828–37. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod66.6.1828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Steuerwald NM, Steuerwald MD, Mailhes JB. Post-ovulatory aging of mouse oocytes leads to decreased MAD2 transcripts and increased frequencies of premature centromere separation and anaphase. Mol Hum Reprod. 2005;11:623–30. doi: 10.1093/molehr/gah231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tripathi A, Chaube SK. Reduction of phosphorylated Thr-161 Cdk1 level participates in roscovitine-induced Fas ligand-mediated apoptosis in rat eggs cultured in vitro. In Vitro Cell Dev Biol-Anim. 2014; doi:10.1007/s11626-014-9812-8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 29.Prasad S, Premkumar KV, Koch B, Chaube SK. Abortive spontaneous egg activation: a pathological condition in mammalian egg. ISSRF News Letter. 2014;14:25–7. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schultz RM, Kopf GS. Molecular basis of mammalian egg activation. Curr Top Dev Biol. 1995;30:21–62. doi: 10.1016/s0070-2153(08)60563-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kubiak JZ. Mouse oocytes gradually develop the capacity for activation during the metaphase II arrest. Dev Biol. 1989;136:537–45. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(89)90279-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Miyazaki S, Yuzaki M, Nakada K, Shirakawa H, Nakanishi S, Nakade S, et al. Block of Ca2+ wave and Ca2+ oscillation by antibody to the inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor in fertilized hamster eggs. Science. 1992;257:251–5. doi: 10.1126/science.1321497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tripathi A, Shrivastav TG, Chaube SK. An increase of granulosa cell apoptosis mediates aqueous neem (Azadirachta indica) leaf extract induced oocyte apoptosis in rat. Int J Appl Basic Med Res. 2013;3:27–36. doi: 10.4103/2229-516X.112238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chaube SK, Prasad PV, Thakur SC, Shrivastav TG. Hydrogen peroxide modulates meiotic cell cycle and induces morphological features characteristic of apoptosis in rat oocytes cultured in vitro. Apoptosis. 2005;10:863–74. doi: 10.1007/s10495-005-0367-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chaube SK, Prasad PV, Khillare B, Shrivastav TG. Extract of Azadirachta indica (Neem) leaf induces apoptosis in rat oocytes cultured in vitro. Fertil Steril. 2006;85:1223–31. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2005.11.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chaube SK, Tripathi A, Khatun S, Misra SK, Prasad PV, Shrivastav TG. Extracellular calcium protects against verapamil-induced metaphase-II arrest and initiation of apoptosis in aged rat eggs. Cell Biol Int. 2009;33:337–43. doi: 10.1016/j.cellbi.2009.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chaube SK, Shrivastav TG, Tiwari M, Prasad S, Tripathi A, Pandey AK. Neem (Azadirachta indica L.) leaf extract deteriorates oocyte quality by inducing ROS-mediated apoptosis in mammals. SpringerPlus. 2014;3:464–8. doi: 10.1186/2193-1801-3-464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tripathi A, Chaube SK. High cytosolic free calcium level signals apoptosis through mitochondria-caspase mediated pathway in rat eggs cultured in vitro. Apoptosis. 2012;17:439–48. doi: 10.1007/s10495-012-0702-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Goud AP, Goud PT, Diamond MP, Abu-Soud HM. Nitric oxide delays oocyte aging. Biochemistry. 2005;44:11361–8. doi: 10.1021/bi050711f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Miao YL, Liu XY, Qiao TW, Miao DQ, Luo MJ, Tan JH. Cumulus cells accelerate aging of mouse oocytes. Biol Reprod. 2005;73:1025–31. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.105.043703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kim NH, Moon SJ, Prather RS, Day BN. Cytoskeletal alteration in aged porcine oocytes and parthenogenesis. Mol Reprod Dev. 1996;43:513–8. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-2795(199604)43:4<513::AID-MRD14>3.0.CO;2-#. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sundstrom P, Nilsson BO, Liedholm P, Larsson E. Ultrastructural characteristics of human oocytes fixed at follicular puncture or after culture. J In Vitro Fert Embryo Transf. 1985;2:195–206. doi: 10.1007/BF01201797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wilding M, Dale B, Marino M, di Matteo L, Alviggi C, Pisaturo ML, et al. Mitochondrial aggregation patterns and activity in human oocytes and preimplantation embryos. Hum Reprod. 2001;16:909–17. doi: 10.1093/humrep/16.5.909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sun QY, Schatten H. Centrosome inheritance after fertilization and nuclear transfer in mammals. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2007;591:58–71. doi: 10.1007/978-0-387-37754-4_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Schatten H. The mammalian centrosome and its functional significance. Histochem Cell Biol. 2008;129:667–86. doi: 10.1007/s00418-008-0427-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Van Wissen B, Bomsel-Helmreich O, Debey P, Eisenberg C, Vautier D, Pennehouat G. Fertilization and ageing processes in non-divided human oocytes after GnRH a treatment: an analysis of individual oocytes. Hum Reprod. 1991;6:879–84. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.humrep.a137444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zenzes MT, Casper RF. Cytogenetics of human oocytes, zygotes, and embryos after in vitro fertilization. Hum Genet. 1992;88:367–75. doi: 10.1007/BF00215667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Liang XW, Zhu JQ, Miao Y, Liu J, Wei L, Lu S, et al. Loss of methylation imprint of Snrpn in postovulatory aging, mouse oocyte. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2008;371:16–21. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2008.03.105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Vaccari S, Weeks JL, II, Hsieh M, Menniti FS, Conti M. Cyclic GMP signaling is involved in the luteinizing hormone-dependent meiotic maturation of mouse oocytes. Biol Reprod. 2009;81:595–604. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.109.077768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cheon YP, Kim SW, Kim SJ, Yeom Y, Cheong C, Ha KS. The role of RhoA in the germinal vesicle breakdown of mouse oocytes. Biochem Biophy Res Commun. 2000;273:997–1002. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2000.3052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pandey A, Chaube SK. A moderate increase of hydrogen peroxide level is beneficial for spontaneous resumption of meiosis from diplotene arrest in rat oocytes cultured in vitro. BioRes Open Access. 2014;3:183–91. doi: 10.1089/biores.2014.0013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tatone C, Emidio GD, Barbaro R, Vento M, Ciriminna R, Artini PG. Effects of reproductive aging and postovulatory aging on the maintenance of biological competence after oocyte vitrification: insights from the mouse model. Theriogenology. 2011;76:864–73. doi: 10.1016/j.theriogenology.2011.04.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zhang N, Wakai T, Fissore RA. Caffeine alleviates the deterioration of Ca (2+) release mechanisms and fragmentation of in vitro-aged mouse eggs. Mol Reprod Dev. 2011;78:684–701. doi: 10.1002/mrd.21366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Liu H, Wang T, Huang K. Cholestane-3B, 5a, 6B-triol-induced reactive oxygen species production promotes mitochondrial dysfunction in isolated mice liver mitochondria. Chem Biol Interact. 2009;179:81–7. doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2008.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Liu L, Trimarchi JR, Keefe DL. Involvement of mitochondria in oxidative stress-induced cell death in mouse zygotes. Biol Reprod. 2000;62:1745–53. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod62.6.1745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Takahashi E, Igarashi H, Kawagoe J, Amita M, Hara S, Kurachi H. Poor embryo development in mouse oocytes aged in vitro is associated with impaired calcium homeostasis. Biol Reprod. 2009;80:493–502. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.108.072017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ito J, Kaneko R, Hirabayashi M. The regulation of calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II during oocyte activation in the rat. J Reprod Dev. 2006;52:439–47. doi: 10.1262/jrd.17047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Yoo JC, Smith LC. Extracellular calcium induces activation of Ca2+/calmodulin dependent protein kinase II and mediates spontaneous activation in rat oocytes. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2007;359:854–9. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.05.181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Shigenaga MK, Hagen TM, Ames BN. Oxidative damage and mitochondrial decay in aging. PNAS. 1994;91:10771–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.23.10771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Tosti E. Calcium ion currents mediating oocyte maturation events. Reprod Biol Endocrinol. 2006;4:26–34. doi: 10.1186/1477-7827-4-26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kubiak JZ, Ciemerych MA, Hupalowska A, Sikora-Polaczek M, Polanski Z. On the transition from the meiotic cell cycle during early mouse development. Int J Dev Biol. 2008;52:201–17. doi: 10.1387/ijdb.072337jk. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Oh JS. Protein tyrosine kinase Wee1B is essential for metaphase II exit in mouse oocytes. Science. 2011;332:462–5. doi: 10.1126/science.1199211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Chan TM, Chen E, Tatoyan A, Shargill NS, Pleta M, Hochstein P. Stimulation of tyrosine-specific protein phophorylation in the rat liver plasma membrane by oxygen radicals. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1986;139:439–45. doi: 10.1016/S0006-291X(86)80010-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Oh JS, Susor A, Schindler K, Schultz RM, Conti M. Cdc25A activity is required for the metaphase II arrest in mouse oocytes. J Cell Sci. 2013;126:1081–5. doi: 10.1242/jcs.115592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kikuchi K, Naito K, Noguchi J, Kaneko H, Tojo H. Maturation/M-phase promoting factor regulates aging of porcine oocytes matured in vitro. Cloning Stem Cells. 2002;4:211–22. doi: 10.1089/15362300260339494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ono T, Mizutani E, Li C, Yamagata K, Wakayama T. Offspring from intracytoplasmic sperm injection of aged mouse oocytes treated with caffeine or MG132. Genesis. 2011;49:460–71. doi: 10.1002/dvg.20756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Zernika-Goetz M, Kubiak JZ, Antony C, Maro B. Cytoskeletal organization of rat oocytes during metaphase II arrest and following abortive activation: a study by confocal laser scanning microscopy. Mol Reprod Dev. 1993;35:165–75. doi: 10.1002/mrd.1080350210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Galat V, Zhou Y, Taborn G, Garton R, Iannaccone P. Overcoming M-III arrest from spontaneous activation in cultured rat oocytes. Cloning Stem Cells. 2007;9:303–14. doi: 10.1089/clo.2006.0059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Cui W, Zhang J, Zhang CX, Jiao GZ, Zhang M, Wang TY. Control of spontaneous activation of rat oocytes by regulating plasma membrane Na+/Ca2+ exchanger activities. Biol Reprod. 2013;88:1–9. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.113.108266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Fissore RA, Kurokawa M, Knott J, Zhang M, Smyth J. Mechanisms underlying oocyte activation and postovulatory ageing. Reproduction. 2002;124:745–54. doi: 10.1530/rep.0.1240745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Ma W, Zhang D, Hou Y, Li YH, Sun QY, Sun XF, et al. Reduced expression of MAD2, BCL2, and MAP kinase activity in pig oocytes after in vitro aging are associated with defects in sister chromatid segregation during meiosis II and embryo fragmentation after activation. Biol Reprod. 2005;72:373–83. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.104.030999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Takai Y, Matikainen T, Juriscova A, Kim MR, Trbovich AM, Fujita E, et al. Caspase-12 compensates for lack of caspase-2 and caspase-3 in female germ cells. Apoptosis. 2007;12:791–800. doi: 10.1007/s10495-006-0022-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Hsu SY, Hsueh AJ. Tissue-specific Bcl-2 protein partners in apoptosis: an ovarian paradigm. Physiol Rev. 2000;80:593–614. doi: 10.1152/physrev.2000.80.2.593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Tatone C, Carbone MC, Gallo R, Delle Monache S, Di Cola M, Alesse E, et al. Age-associated changes in mouse oocytes during postovulatory in vitro culture: possible role for meiotic kinases and survival factor BCL2. Biol Reprod. 2006;74:395–402. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.105.046169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Verbert L, Lee B, Kocks SL, Assefa Z, Parys JB, Missiaen L, et al. Caspase-3-truncated type 1 inositol 1, 4, 5-triphosphate receptor enhances intracellular Ca2+ leak and disturbs Ca2+ signalling. Biol Cell. 2008;1000:39–49. doi: 10.1042/BC20070086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]