Abstract

Objective:

Research has shown that U.S. military veterans are at risk relative to the general adult population for excessive alcohol consumption, and veterans of the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq (Operation Enduring Freedom [OEF], Operation Iraqi Freedom [OIF], and Operation New Dawn [OND]) particularly so. The purpose of this study was to examine the efficacy of a brief personalized drinking feedback intervention tailored for veterans.

Method:

All veterans who presented to the OEF/OIF/OND Seamless Transition Clinic at the Harry S. Truman Memorial Veterans’ Hospital (Columbia, MO) were eligible to participate. Participants were 325 veterans (93% male; 82% White, 75% Army, Mage = 32.20 years) who were randomly assigned to one of two conditions: personalized drinking feedback (PDF) or educational information (EDU). Those in the PDF condition received personalized information about their alcohol use, including social norms comparisons, risks associated with reported drinking levels, and a summary of their alcohol-related problems. Follow-up assessments were completed at 1 and 6 months after intervention (response rates = 93% and 86%, respectively).

Results:

Results indicated a significant (p < .05) Omnibus Group × Time effect for estimated peak blood alcohol concentration, although tests of simple main effects did not indicate between-group differences at the individual follow-up points. Among baseline abstainers, those in the PDF condition were more likely than those in the EDU condition to remain an abstainer at 6-month follow-up (p < .05).

Conclusions:

These findings provide preliminary support for the efficacy of a brief, inexpensive alcohol prevention/intervention for young adult military veterans.

U.s. military veterans are an at-risk population for problems related to alcohol consumption (Bradley et al., 2003; Bridevaux et al., 2004; Wagner et al., 2007). Further, research suggests that alcohol misuse among veterans of the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq (Operation Enduring Freedom [OEF], Operation Iraqi Freedom [OIF], and Operation New Dawn [OND]) may be particularly problematic (Hawkins et al., 2010; Kehle et al., 2012). The Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) has recognized the issue of alcohol misuse among veterans and mandates annual alcohol misuse screening for all patients (Hawkins et al., 2007). Yet, evidence suggests that many veterans who engage in alcohol misuse do not receive any services or advice from their providers (Kaner et al., 2007; Solberg et al., 2008). For example, in a study of more than 6,000 VA patients who screened positive for alcohol misuse, only 53% had documentation of the mandated brief intervention (Lapham et al., 2012). Other studies have shown that only about one third of OEF/OIF/OND veterans who met criteria for hazardous drinking were counseled by a VA provider to cut back or eliminate their drinking (Calhoun et al., 2008; Hawkins et al., 2010). Lack of time, concerns about patient defensiveness, and lack of expertise have been identified as barriers to addressing alcohol misuse in the VA setting (Barry et al., 2004). These findings highlight the need to explore alternative methods for delivering brief interventions to veterans misusing alcohol.

A personalized drinking feedback (PDF) intervention has the potential to address the aforementioned barriers to implementing brief interventions in a VA setting. In a PDF intervention, the individual completes alcohol-related measures that are used to generate a personalized feedback summary. The content of the feedback often includes information such as social norms comparisons, problems associated with alcohol use, and dollars spent on alcohol (e.g., Dimeff et al., 1999; Hester et al., 2005).

PDF interventions have typically been delivered in the context of a brief meeting with a clinician, the efficacy of which is well established (e.g., Carey et al., 2007; Cronce & Larimer, 2011). Researchers have also examined the efficacy of PDF interventions delivered in the absence of clinician contact, with many finding that the intervention was efficacious relative to a control condition at reducing alcohol use and/or alcohol-related problems (e.g., Butler & Correia, 2009; Cunningham et al., 2010; Hester et al., 2005; Kypri et al., 2004; Larimer et al., 2007; Martens et al., 2010). However, the two studies examining PDF-only interventions among veterans have not provided clear evidence regarding its efficacy. Cucciare and colleagues (2013) examined a PDF-only intervention plus treatment as usual versus just treatment as usual among 167 older veterans who screened positive for alcohol misuse. They found significant reductions in alcohol use and alcohol-related problems over a 6-month follow-up for both conditions, but no additive effect of the PDF-only intervention. McDevitt-Murphy and colleagues (2014) examined a PDF-only intervention versus PDF with a motivational interviewing counseling session among 68 OEF/OIF/OND veterans. Significant reductions in alcohol use and alcohol-related problems over a 6-month follow-up were found for both conditions, but the findings are limited by the relatively small sample size and the lack of a control condition.

The purpose of the present study was to examine the efficacy of a PDF-only intervention among OEF/OIF/OND veterans. We hypothesized that participants randomized to the PDF condition would report a lower peak blood alcohol concentration (BAC), fewer drinks per week, and fewer alcohol-related problems at follow-up than those in an education-only control condition. We also hypothesized that participants in the PDF condition who reported no alcohol use over the preceding 30 days would be more likely than those in the control condition to report no alcohol use at follow-up.

Method

Participants and procedure

Participants were randomly assigned to one of two conditions, PDF or educational information (EDU), and provided self-report assessment data at baseline and at 1-month and 6-month follow-ups. All veterans who presented to the OEF/OIF/OND Seamless Transition Clinic, a one-time clinic at the Harry S. Truman Memorial Veterans’ Hospital (Columbia, MO) for returning combat veterans to assess postdeployment needs, were eligible to participate. Veterans with upcoming clinic appointments were mailed a letter that noted the purpose of the study and were contacted by research staff 1 week before their appointment to describe the study, answer questions, and assess interest in participating. Those who participated in the study met with research staff before or after their appointment in a private room to complete the informed consent questionnaire and baseline battery of questions. Four hundred nine veterans were approached to participate in the study, 325 of whom enrolled in the trial.

Measures

Alcohol use.

A modified Daily Drinking Questionnaire (Collins et al., 1985) was used to assess average number of drinks per week. Participants were provided with a definition of a standard drink and asked to indicate how many drinks they typically consumed on each day of the week over the past 30 days. We calculated estimated peak BAC over the preceding 30 days by asking participants to indicate the largest number of drinks they had consumed on a single occasion over that timeframe and the number of hours they consumed alcohol on that occasion (see Matthews & Miller, 1979).

Alcohol-related problems.

The Short Inventory of Problems, a 15-item measure designed for adults that is a brief version of the Drinker Inventory of Consequences (Miller et al., 1995), assessed alcohol-related problems. For each item, participants indicated whether they had experienced the problem. At baseline, we asked participants to report problems experienced over the past 6 months, as responses from the measure were used as part of the personalized feedback (see below). To maintain consistency at our two follow-ups, however, we asked participants to indicate problems experienced over the past month. Internal consistency estimates for the measure ranged from .87 (baseline) to .88 (1-month and 6-month follow-up) in the present study.

Demographics.

Participants completed a measure that assessed basic demographic information. In addition, at each follow-up, participants indicated if they had received any formal substance use or mental health treatment since enrolling in the study.

Interventions

Personalized drinking feedback.

Participants in the PDF condition received their feedback via paper printout and reviewed the following information in a private room in the clinic for at least 10 minutes: (a) social norms data on how their drinks per week compared with gender-specific national norms and veteran-specific gender norms; (b) their estimated BAC and related risks on their peak, typical weekend, and typical weekday drinking over the past 30 days; (c) their level of risk as identified by the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test–consumption questions (Bush et al., 1998); (d) alcohol-related problems from the Short Inventory of Problems; (e) health/mental health problems associated with hazardous alcohol use (e.g., poor sleep); (f) use of protective behavioral strategies designed to limit excessive alcohol consumption; (g) calories consumed from alcohol in a typical week; and (h) estimated yearly financial costs associated with alcohol use. After reviewing the information, participants were asked if they had any questions about the materials.

Educational information.

Participants in the EDU condition reviewed general educational information about the effects of alcohol on the body, such as how alcohol enters the body and its general effects on the brain and other organs. They were instructed to review these materials for at least 10 minutes in the clinic and were provided the opportunity to ask questions about the information.

Data analytic plan

We used repeated-measures analysis of variance, with condition as a between-groups variable, to assess for treatment effects on estimated peak BAC and drinks per week. Because the baseline assessment timeframe of alcohol-related problems differed from the follow-up assessment timeframe, we used analysis of covariance with baseline scores as a covariate to assess for treatment effects on alcohol-related problems. Separate analyses were conducted for three groups: the full sample, those who reported any alcohol use at baseline in the preceding 30 days (“drinkers only”), and men/women who reported 5+/4+ drinks on a single occasion in the preceding 30 days (“heavy drinkers”). Last, we used logistic regression analysis to determine whether there were treatment effects on the likelihood of a nondrinker at baseline remaining a nondrinker at follow-up. Gender and receiving substance use/mental health treatment since enrolling in the study were examined as covariates/moderator variables, but results were nearly identical with or without the variables in the model. Thus, all analyses are reported without covariates and were conducted in an intent-to-treat framework. Analyses were conducted with SPSS Version 21.

Results

Preliminary analyses

The majority of the participants were male (93.2%), White (82.2%), served in the Army (74.8%), and reported one (56.3%) or two (30.8%) deployments to Iraq and/or Afghanistan. The mean age was 32.20 years (SD = 8.18). At baseline, participants reported an average of 10.66 drink per week (SD = 13.82), 6.55 drinks on their peak drinking occasion over the past 30 days (SD = 6.99), and 1.78 alcohol-related problems (SD = 2.69). There were no between-group differences on any demographic characteristic, on receiving substance use/mental health treatment since enrolling in the study, on alcohol use or peak BAC, or on follow-up rates (93.2% at 1 month and 85.5% at 6 months). There were baseline differences on alcohol-related problems, with those in the PDF condition reporting more problems than those in the EDU condition (2.17 vs. 1.47, p < .05).

Intervention effects on alcohol use and alcohol-related problems

Peak blood alcohol concentration.

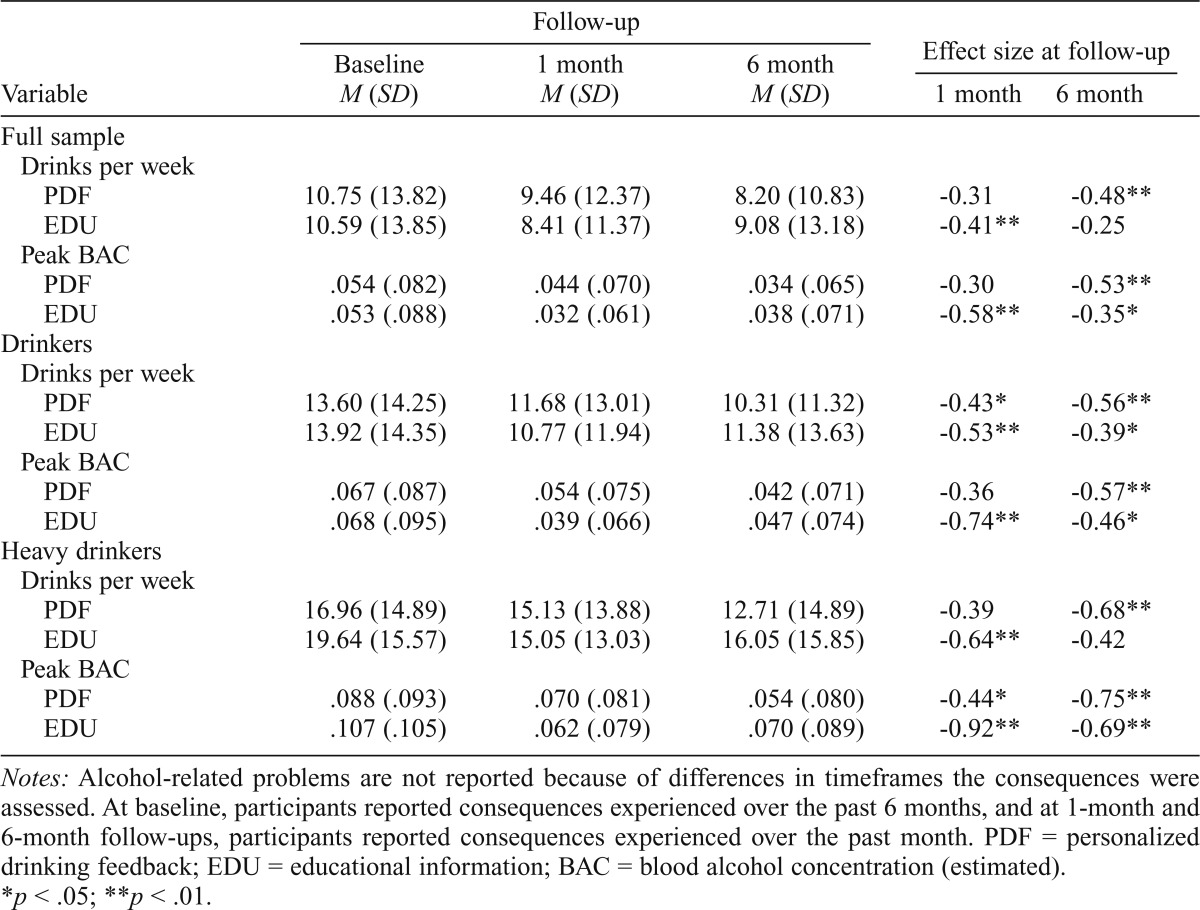

Within-group differences between participants in the PDF and EDU conditions are presented in Table 1. The Group × Time effect was statistically significant for the full sample, Wilks’s λ = .98, F(2, 318) = 3.91, p = .02,  = .02, drinkers-only subsample, Wilks’s λ = .97, F(2, 244) = 3.76, p = .02,

= .02, drinkers-only subsample, Wilks’s λ = .97, F(2, 244) = 3.76, p = .02,  = .03, and heavy drinking subsample, Wilks’s λ = .96, F(2, 163) = 3.49, p = .03,

= .03, and heavy drinking subsample, Wilks’s λ = .96, F(2, 163) = 3.49, p = .03,  = .04. As illustrated in Table 1, participants in the PDF condition reported significant continuous decreases in peak BAC from baseline to 6-month follow-up, whereas participants in the EDU condition reported decreases between baseline and 1-month follow-up, followed by increases between the 1-month and 6-month follow-up. However, simple between-group differences at each time point were not statistically significant (p > .05).

= .04. As illustrated in Table 1, participants in the PDF condition reported significant continuous decreases in peak BAC from baseline to 6-month follow-up, whereas participants in the EDU condition reported decreases between baseline and 1-month follow-up, followed by increases between the 1-month and 6-month follow-up. However, simple between-group differences at each time point were not statistically significant (p > .05).

Table 1.

Means (and standard deviations) and within-person effect sizes (Cohen’s d) on outcomes by condition

| Follow-up |

Effect size at follow-up |

||||

| Variable | Baseline M (SD) | 1 month M (SD) | 6 month M (SD) | 1 month | 6 month |

| Full sample | |||||

| Drinks per week | |||||

| 10.75 (13.82) | 9.46 (12.37) | 8.20 (10.83) | -0.31 | -0.48** | |

| EDU | 10.59 (13.85) | 8.41 (11.37) | 9.08 (13.18) | -0.41** | -0.25 |

| Peak BAC | |||||

| .054 (.082) | .044 (.070) | .034 (.065) | -0.30 | -0.53** | |

| EDU | .053 (.088) | .032 (.061) | .038 (.071) | -0.58** | -0.35* |

| Drinkers | |||||

| Drinks per week | |||||

| 13.60 (14.25) | 11.68 (13.01) | 10.31 (11.32) | -0.43* | -0.56** | |

| EDU | 13.92 (14.35) | 10.77 (11.94) | 11.38 (13.63) | -0.53** | -0.39* |

| Peak BAC | |||||

| .067 (.087) | .054 (.075) | .042 (.071) | -0.36 | -0.57** | |

| EDU | .068 (.095) | .039 (.066) | .047 (.074) | -0.74** | -0.46* |

| Heavy drinkers | |||||

| Drinks per week | |||||

| 16.96 (14.89) | 15.13 (13.88) | 12.71 (14.89) | -0.39 | -0.68** | |

| EDU | 19.64 (15.57) | 15.05 (13.03) | 16.05 (15.85) | -0.64** | -0.42 |

| Peak BAC | |||||

| .088 (.093) | .070 (.081) | .054 (.080) | -0.44* | -0.75** | |

| EDU | .107 (.105) | .062 (.079) | .070 (.089) | -0.92** | -0.69** |

Notes: Alcohol-related problems are not reported because of differences in timeframes the consequences were assessed. At baseline, participants reported consequences experienced over the past 6 months, and at 1-month and 6-month follow-ups, participants reported consequences experienced over the past month. PDF = personalized drinking feedback; EDU = educational information; BAC = blood alcohol concentration (estimated).

p < .05;

p < .01.

Drinks per week.

There were no significant Group × Time effects for the full sample, Wilks’s λ = .99, F(2, 321) = 1.94, p > .05,  = .01, drinkers-only subsample, Wilks’s λ = .99, F(2, 248) = 1.34, p > .05,

= .01, drinkers-only subsample, Wilks’s λ = .99, F(2, 248) = 1.34, p > .05,  = .01, or heavy drinkers subsample, Wilks’s λ = .97, F(2, 163) = 2.38, p >.05,

= .01, or heavy drinkers subsample, Wilks’s λ = .97, F(2, 163) = 2.38, p >.05,  = .03. Within-group patterns of change were similar to those observed for peak BAC.

= .03. Within-group patterns of change were similar to those observed for peak BAC.

Alcohol-related problems.

There were no significant between-group effects, controlling for baseline values, for the full sample at 1-month, F(1, 322) = 1.63, p >.05,  = .005, or at 6-month follow-up, F(1, 322) = 0.04, p >.05,

= .005, or at 6-month follow-up, F(1, 322) = 0.04, p >.05,  = .000; for the drinkers-only subsample at 1-month, F(1, 248) = 1.03, p >.05,

= .000; for the drinkers-only subsample at 1-month, F(1, 248) = 1.03, p >.05,  = .004, or at 6-month follow-up, F(1, 248) = 0.50, p >.05,

= .004, or at 6-month follow-up, F(1, 248) = 0.50, p >.05,  = .002; or for heavy drinkers subsample at 1-month, F(1, 163) = 1.28, p >.05,

= .002; or for heavy drinkers subsample at 1-month, F(1, 163) = 1.28, p >.05,  = .008, or at 6-month follow-up, F(1, 163) = 0.05, p >.05,

= .008, or at 6-month follow-up, F(1, 163) = 0.05, p >.05,  = .000.

= .000.

Intervention effects on abstainers

Twenty-eight veterans (18%) in the PDF condition and 34 veterans (20%) in the EDU condition abstained from alcohol use at baseline. At 1-month follow-up, there was no difference between conditions on abstaining from alcohol, B = 0.49, χ2(1, N = 62) = .46, p > .05. There were, however, significant differences at 6-month follow-up, B = -1.95, χ2(1, N = 62) = 4.48 p < .05. Veterans in the PDF condition were more likely to continue to abstain at the 6-month follow-up than those in the EDU condition (96% vs. 79%).

Discussion

Results from this study provided some support for our hypotheses. There were between-group differences on estimated peak BAC but not for drinks per week or alcohol-related problems. Despite the overall intervention effect on the peak BAC variable, the pattern of change between the two conditions, and the fact that simple between-group differences at each time point were not statistically significant, does not allow for clear conclusions regarding the impact of the PDF intervention. In the PDF condition, there was a linear trend over time for the full sample, whereas in the EDU condition, there was an initial drop in BAC at 1 month followed by an increase at 6 months. These trends also occurred for the drinks-per-week variable, although overall between-group differences were not statistically significant. One potential explanation for these findings is that a PDF intervention may have more lasting effects than providing educational information about alcohol use (e.g., White et al., 2007), and perhaps a similar pattern occurred in the present study.

The finding that those in the PDF condition who did not use alcohol at baseline were more likely than those in the EDU condition to continue to not use at 6-month follow-up is consistent with findings from another examination of a PDF-only intervention (Larimer et al., 2007). PDF interventions are not typically designed for individuals who do not drink, so it is interesting that they may have a preventative effect among those who abstain from alcohol use. One possible explanation for such an effect is that some of the feedback content serves to reinforce abstinence from alcohol (e.g., social norms feedback reinforcing the notion that many veterans do not drink).

The findings from this project should be considered in terms of the intensity of the study interventions. A formal cost/benefit analysis was beyond the scope of the present project, but our impression is that the PDF intervention was relatively easy and efficient to implement as part of the Seamless Transition Clinic, without any disruption of participants’ meetings with providers during their scheduled appointment. A PDF-only intervention requires some coordination with administrative and clinical staff but does not require expenses associated with in-person clinical services (e.g., hiring and supervising clinical staff). Further, the time-related burdens on participants are relatively minimal, as participants only need to respond to the questionnaires necessary to create the feedback. Thus, even if effect sizes are relatively small, the low cost, low response burden, and ease of implementation make PDF-based interventions an attractive candidate for wider dissemination in a system like the VA.

This study contained several limitations, such as a lack of long-term follow-up, the use of self-report data, no fidelity checks to ensure that participants read their intervention materials, and the homogeneity of the sample. Despite these limitations, the findings from the present trial are meaningful additions to the literature on brief alcohol interventions, particularly interventions targeted at veterans. We encourage future researchers to build on our findings by conducting follow-up studies with a longer follow-up period and larger, more diverse samples. Another important direction would be to examine the efficacy of individual components of the personalized feedback. Finally, developing and examining the efficacy of brief interventions that use technology to deliver personalized feedback to at-risk populations like veterans, such as via email, text, and/or other novel communication methods, seems warranted.

Footnotes

This project was supported by National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism Grant R21AA020180. This research is the result of work supported with resources and the use of facilities at the Harry S. Truman Memorial Veterans’ Hospital.

References

- Barry K. L., Blow F. C., Willenbring M. L., McCormick R., Brockmann L. M., Visnic S. Use of alcohol screening and brief interventions in primary care settings: Implementation and barriers. Substance Abuse. 2004;25:27–36. doi: 10.1300/J465v25n01_05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradley K. A., Bush K. R., Epler A. J., Dobie D. J., Davis T. M., Sporleder J. L., Kivlahan D. R. Two brief alcohol-screening tests from the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT): Validation in a female Veterans Affairs patient population. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2003;163:821–829. doi: 10.1001/archinte.163.7.821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bridevaux I. P., Bradley K. A., Bryson C. L., McDonell M. B., Fihn S. D. Alcohol screening results in elderly male veterans: Association with health status and mortality. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2004;52:1510–1517. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52414.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bush K., Kivlahan D. R., McDonell M. B., Fihn S. D., Bradley K. A. The AUDIT Alcohol Consumption Questions (AUDIT-C): An effective brief intervention screening test for problem drinking. Archives of Internal Medicine. 1998;158:1789–1795. doi: 10.1001/archinte.158.16.1789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butler L. H., Correia C. J. Brief alcohol intervention with college student drinkers: Face-to-face versus computerized feedback. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2009;23:163–167. doi: 10.1037/a0014892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calhoun P. S., Elter J. R., Jones E. R., Jr., Kudler H., Straits-Tröster K. Hazardous alcohol use and receipt of risk-reduction counselling among U.S. veterans of the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2008;69:1686–1693. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v69n1103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carey K. B., Scott-Sheldon L. A., Carey M. P., DeMartini K. S. Individual-level interventions to reduce college student drinking: A meta-analytic review. Addictive Behaviors. 2007;32:2469–2494. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins R. L., Parks G. A., Marlatt G. A. Social determinants of alcohol consumption: The effects of social interaction and model status on the self-administration of alcohol. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1985;53:189–200. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.53.2.189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cronce J. M., Larimer M. E. Individual-focused approaches to the prevention of college student drinking. Alcohol Research & Health: The Journal of the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. 2011;34:210–221. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cucciare M. A., Weingardt K. R., Ghaus S., Boden M. T., Frayne S. M. A randomized controlled trial of a web-delivered brief alcohol intervention in Veterans Affairs primary care. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2013;74:428–436. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2013.74.428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham J. A., Wild T. C., Cordingley J., Van Mierlo T., Humphreys K. Twelve-month follow-up results from a randomized controlled trial of a brief personalized feedback intervention for problem drinkers. Alcohol and Alcoholism. 2010;45:258–262. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agq009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dimeff L. A., Baer J. S., Kivlahan D. R., Marlatt G. A. Brief alcohol screening and intervention for college students: A harm reduction approach. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins E. J., Kivlahan D. R., Williams E. C., Wright S. M., Craig T., Bradley K. A. Examining quality issues in alcohol misuse screening. Substance Abuse. 2007;28:53–65. doi: 10.1300/J465v28n03_06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins E. J., Lapham G. T., Kivlahan D. R., Bradley K. A. Recognition and management of alcohol misuse in OEF/OIF and other veterans in the VA: A cross-sectional study. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2010;109:147–153. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2009.12.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hester R. K., Squires D. D., Delaney H. D. The Drinker’s Check-up: 12-month outcomes of a controlled clinical trial of a standalone software program for problem drinkers. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2005;28:159–169. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2004.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaner E. F., Beyer F., Dickinson H. O., Pienaar E., Campbell F., Schlesinger C., Burnand B. Effectiveness of brief alcohol interventions in primary care populations. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, Issue. 2007;2 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004148.pub3. Article No. CD004148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kehle S. M., Ferrier-Auerbach A. G., Meis L. A., Arbisi P. A., Erbes C. R., Polusny M. A. Predictors of postdeployment alcohol use disorders in National Guard soldiers deployed to Operation Iraqi Freedom. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2012;26:42–50. doi: 10.1037/a0024663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kypri K., Saunders J. B., Williams S. M., McGee R. O., Langley J. D., Cashell-Smith M. L., Gallagher S. J. Web-based screening and brief intervention for hazardous drinking: A double-blind randomized controlled trial. Addiction. 2004;99:1410–1417. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2004.00847.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lapham G. T., Achtmeyer C. E., Williams E. C., Hawkins E. J., Kivlahan D. R., Bradley K. A. Increased documented brief alcohol interventions with a performance measure and electronic decision support. Medical Care. 2012;50:179–187. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3181e35743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larimer M. E., Lee C. M., Kilmer J. R., Fabiano P. M., Stark C. B., Geisner I. M., Neighbors C. Personalized mailed feedback for college drinking prevention: A randomized clinical trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2007;75:285–293. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.75.2.285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martens M. P., Kilmer J. R., Beck N. C., Zamboanga B. L. The efficacy of a targeted personalized drinking feedback intervention among intercollegiate athletes: A randomized controlled trial. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2010;24:660–669. doi: 10.1037/a0020299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthews D. B., Miller W. R. Estimating blood alcohol concentration: Two computer programs and their applications in therapy and research. Addictive Behaviors. 1979;4:55–60. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(79)90021-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDevitt-Murphy M. E., Murphy J. G., Williams J. L., Monahan C. J., Bracken-Minor K. L., Fields J. A. Randomized controlled trial of two brief alcohol interventions for OEF/OIF veterans. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2014;82:562–568. doi: 10.1037/a0036714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller W. R., Tonigan J. S., Longabaugh R. The Drinker Inventory of Consequences (DrInC): An instrument for assessing averse consequence of alcohol abuse (test manual) (NIAAA Project MATCH Monograph Series, Vol. 4, NIH Publication No. 95–3911) Rockville, MD: Department of Health and Human Services; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Solberg L. I., Maciosek M. V., Edwards N. M. Primary care intervention to reduce alcohol misuse ranking its health impact and cost effectiveness. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2008;34:143–152. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2007.09.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner T. H., Harris K. M., Federman B., Dai L., Luna Y., Humphreys K. Prevalence of substance use disorders among veterans and comparable nonveterans from the National Survey on Drug Use and Health. Psychological Services. 2007;4:149–157. [Google Scholar]

- White H. R., Mun E. Y., Pugh L., Morgan T. J. Long-term effects of brief substance use interventions for mandated college students: Sleeper effects of an in-person personal feedback intervention. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2007;31:1380–1391. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2007.00435.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]