Abstract

Acute leukemia characterized by chromosomal rearrangements requires additional molecular disruptions to develop into full-blown malignancy1,2, yet the cooperative mechanisms remain elusive. Using whole-genome sequencing of a pair of monozygotic twins discordant for MLL (also called KMT2A) gene-rearranged leukemia, we identified a transforming MLL-NRIP3 fusion gene3 and biallelic mutations in SETD2 (encoding a histone H3K36 methyltransferase)4. Moreover, loss-of-function point mutations in SETD2 were recurrent (6.2%) in 241 patients with acute leukemia and were associated with multiple major chromosomal aberrations. We observed a global loss of H3K36 trimethylation (H3K36me3) in leukemic blasts with mutations in SETD2. In the presence of a genetic lesion, downregulation of SETD2 contributed to both initiation and progression during leukemia development by promoting the self-renewal potential of leukemia stem cells. Therefore, our study provides compelling evidence for SETD2 as a new tumor suppressor. Disruption of the SETD2-H3K36me3 pathway is a distinct epigenetic mechanism for leukemia development.

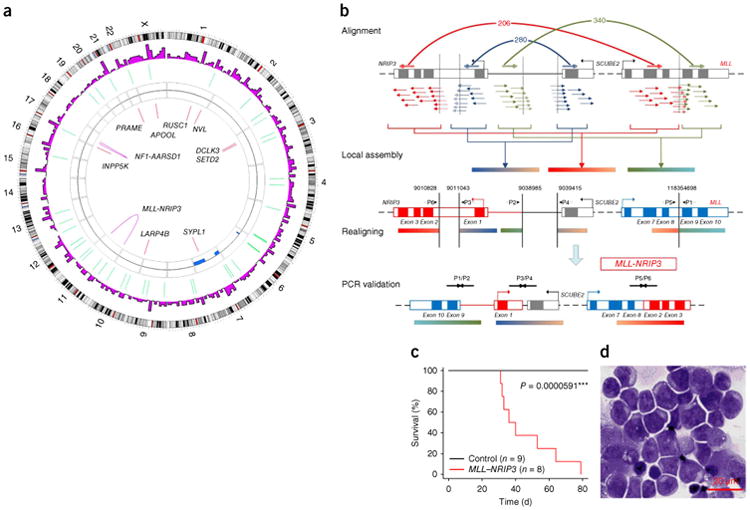

Chromosomal translocations occur in more than 50% of human leukemias and lymphomas5,6 and are increasingly being observed in solid tumors7. However, chromosomal translocation alone may not be sufficient to drive full-blown disease, even in pediatric leukemias8,9. To define cooperating genetic and epigenetic abnormalities that are associated with primary chromosomal translocations during the development of leukemia, we focused on a 3-year-old female monozygotic twin pair that is discordant for MLL-associated acute myeloid leukemia (AML) and has been morphologically classified as FAB-M5 (Supplementary Figs. 1 and 2 and Supplementary Note). FISH analysis indicated chromosomal translocation disrupting MLL in the patient with leukemia but not her twin sister (Supplementary Fig. 1). To characterize the unknown MLL fusion gene that resulted from the chromosomal rearrangement and detect all potential cooperative somatic genomic changes, we obtained 55× and 62× whole-genome sequencing (WGS) data covering 98.48% and 98.46% of the genomes of CD56+CD64+ leukemia cells from the patient and peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) from her healthy twin sister, respectively (Supplementary Table 1). With PBMCs from the healthy twin as a germline and normal tissue control, we revealed an intrachromosomal translocation that gave rise to the MLL-NRIP3 fusion gene3 in the twin with leukemia (Fig. 1a,b and Supplementary Figs. 3 and 4). Retrovirus-mediated ectopic expression of MLL-NRIP3 in mouse hematopoietic cells was able to induce the same type of myeloid leukemia as that of the patient in a mouse transplant model (Fig. 1c,d and Supplementary Fig. 5). The median onset of the AML was 46.5 days (Fig. 1c), suggesting additional cooperative events in the development of induced leukemia.

Figure 1.

Mutational and functional analysis of the MLL-NRIP3 fusion gene identified a monozygotic twin pair discordant for MLL-rearranged leukemia. (a) Circos41 plot showing the genetic alterations identified in the twin with leukemia, using the healthy twin as a normal control. Genes with validated coding single-nucleotide variants (SNVs) and fusion genes are indicated. CNV, copy-number variation. (b) Genetic events in the formation of the MLL-NRIP3 fusion gene. Sequencing reads, shown as groups of short arrows, were aligned onto the non-rearranged MLL-NRIP3 locus on chromosome 11 (top row, labeled alignment). Paired reads mapped onto six non-continued regions were identified and assembled into three contigs (second row, labeled local assembly). Non-continued regions connected by paired reads are joined by a bracket (below the MLL-NRIP3 locus) and a curved line (above the MLL-NRIP3 locus), with the numbers of supportive paired reads shown The three assembled contigs were realigned onto the non-rearranged loci to identify potential chromosomal break points, which are indicated by five vertical lines (third row, labeled realigning). The rearranged MLL-NRIP3 locus was assembled. PCR primers (P1/P2, P3/P4 and P5/P6) were designed to confirm the fusion conjunctions resulting from the chromosomal rearrangements (fourth row, labeled PCR validation, and supplementary Fig. 4). (c) Survival curve for recipients of the bone marrow cells transduced with MLL-NRIP3 or the empty vector control (P = 5.91 × 10−5, Mantel-Haenszel test). MLL-NRIP3 induced myeloid leukemia with a median survival of 46.5 days. (d) Immature myeloblasts are shown by the morphology of the bone marrow biopsy specimen from a mouse with MLL-NRIP3 leukemia. Throughout the figures, * indicates significance passing the threshold of P < 0.05 ** indicates passing the threshold of P < 0.01, and *** indicates passing the threshold of P < 0.001.

In searching for potential cooperative somatic genomic alterations in the twin with leukemia (Fig. 1a, Supplementary Table 2 and Supplementary Figs. 3, 4, 6 and 7), we identified two non-synonymous point mutations in SETD2 located in chromosome 3p (Supplementary Table 2), which encodes the only histone-modifying enzyme that is responsible for catalyzing H3K36me3 (ref. 10). Analysis of sequencing reads and further genotyping using Sequenom assay showed an approximate 50% allele frequency for each of the two mutations (Supplementary Fig. 8), suggesting that these mutations are present in almost all of the leukemic cells. Methylation of H3K36 and H3K79 are the two major histone modifications that are involved in transcriptional elongation11. Given the previously documented role of MLL fusion protein–mediated H3K79 methylation in leukemogenesis1, it was of great interest for us to explore whether a distinct epigenetic pathway represented by SETD2-H3K36 could be a cooperative event in the development of MLL-rearranged leukemia. Therefore, we focused all subsequent studies on the role of SETD2 and its underlying mechanism in the development of leukemia.

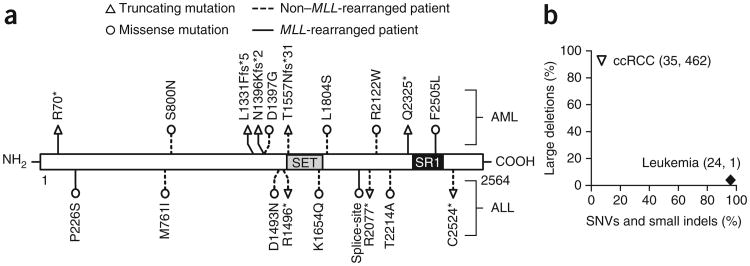

To examine the prevalence of SETD2 mutations in a general population of patients with leukemia, we next used PCR to amplify all 21 exons of SETD2 and carried out Sanger sequencing on 134 AML and 107 acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) samples (Supplementary Tables 3–6). We identified 19 somatic SETD2 mutations in 15 patients (Fig. 2 and Table 1). We observed a higher frequency of SETD2 mutations in MLL-rearranged patients with leukemia (22.2%, 6 out of 27) compared to patients with leukemia that did not have MLL rearrangements (4.6%, 8 out of 173) in the patient cohort (P = 0.005; Fig. 2 and Table 1). Notably, SETD2 mutation is not unique to MLL-rearranged leukemia, as the SETD2-mutated patients also harbored a number of other known genetic aberrations, including AML1 (also called RUNX1)-ETO (also called RUNX1T1) or mutations in CEBPA or NPM1 (Table 1 and Supplementary Tables 3–6). Specifically, a majority of these patients with mutated SETD2 (86.7%, 13 out of 15) had one additional major genetic aberration. Thus, these results demonstrate that SETD2 mutations are recurrent in acute human leukemia and are associated with chromosomal abnormalities that are known to be driver mutations in leukemogenesis.

Figure 2.

Mutational analysis of SETD2 in patients with acute leukemia. (a) SETD2 mutations in patients with acute leukemia. The locations of the SET and SRI domains of SETD2 are indicated. The type and position of each identified mutation is shown. HGVS notations corresponding to the abbreviations of the SETD2 mutations used here are listed in Supplementary Table 3. (b) Distinct mutation spectrum of SETD2 in patients with either acute leukemia or ccRCC. Mutational information of SETD2 was obtained from the current study, a previous report by Zhang et al.39 and the TCGA Research Network16. The percentages of SNVs, small insertions or deletions (indels) and large deletions in SETD2 are shown, with the number of each of these variants in parentheses.

Table 1. Major genetic abnormalities identified in SETD2-mutated patients with leukemia.

| Total: 241a | Rearranged MLL: 27 | WT MLL: 173 | Unknown: 41 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mutated SETD2: 15 | 6 (22.2%b) | AML: 4c | MLL-NRIP3: 1d | 8 (4.6%) | AML: 2 | AML1-ETO: 1 | 1 |

| MLL-AF10: 1d | NPM1 and CEBPA: 1d | ||||||

| Unknown partner: 1 | |||||||

| MLL-PTD: 1 | |||||||

| ALL: 2 | MLL-AF9: 1 | ALL: 6 | TEL-AML1: 1 | ||||

| MLL-AF4: 1 | TCR: 1d | ||||||

| TCR: 2 | |||||||

| MDR1: 1 | |||||||

| Unknown: 1 | |||||||

| WT SETD2: 226 | 21 | AML: 14 | 165 | AML: 77 | 40 | ||

| ALL: 7 | ALL: 86 | ||||||

The number of patients in each leukemia group.

The percentages of patients with SETD2 mutations in the groups with wild-type (WT) and rearranged MLL.

The number of patients with specific genetic mutations.

Biallelic SETD2 mutation.

The mutation spectrum may imply the functional role of an affected gene acting as a tumor suppressor or oncogene in leukemia development12. We found that 8 of the total 19 SETD2 mutations (42.1%) identified in 241 patients with acute leukemia were either nonsense or frameshift mutations that truncate a portion of the C terminus domain of SETD2 (Fig. 2a and Supplementary Table 3). In addition, 26.7% (4 out of 15) of the SETD2-mutated patients carried two mutations on SETD2 (Table 1 and Supplementary Table 3). cDNA or DNA clone sequencing confirmed that each of the two mutations occurs on separate alleles of SETD2 in individual patients, indicating a biallelic nature (Supplementary Table 3). These data are consistent with the notion of truncating mutations and/or multiple hits on the same gene, which are common mechanisms for inactivating the normal function of tumor-suppressor genes (Supplementary Fig. 9). Considering the loss-of-function feature of the SETD2 mutations identified, we further explored whether additional genetic and epigenetic mechanisms operate to inactivate SETD2 in acute leukemia (Supplementary Figs. 10 and 11). We found no evidence of SETD2 gene deletion in our cohort of 241 patients with acute leukemia by Sequenom genotyping across chromosome 3 (Supplementary Fig. 10a). Using an established genomic analysis method13,14, we detected large genomic deletions encompassing SETD2 in patients with MLL fusion, as well as patients with TEL (also called ETV6)-AML1 or BCR-ABL, but at a very low frequency (≤0.6%) (Supplementary Table 7 and Supplementary Fig. 11). This finding is in sharp contrast to the frequent (>80%) large deletions in SETD2 in patients with clear cell renal cell carcinoma (ccRCC) detected by the same genomic analysis (Supplementary Fig. 12) and by SNP array data15,16 (Fig. 2b). In addition to genetic mutations, we detected downregulated mRNA expression of SETD2 in patients with lymphoma and a subset of patients with leukemia at an ∼9.0% frequency using expression data deposited in the Oncomine data set17 (Supplementary Fig. 10b,c). However, downregulation of SETD2 is unlikely due to epigenetic silencing, as we found no hypermethylation of SETD2 promoter DNA in 194 AMLs from the DNA methylation data set derived from The Cancer Genome Atlas project2 (TCGA; Supplementary Fig. 10d,e). Together these analyses strongly indicate that SETD2 inactivation occurs primarily through point mutation and downregulation of gene expression in hematologic malignancies.

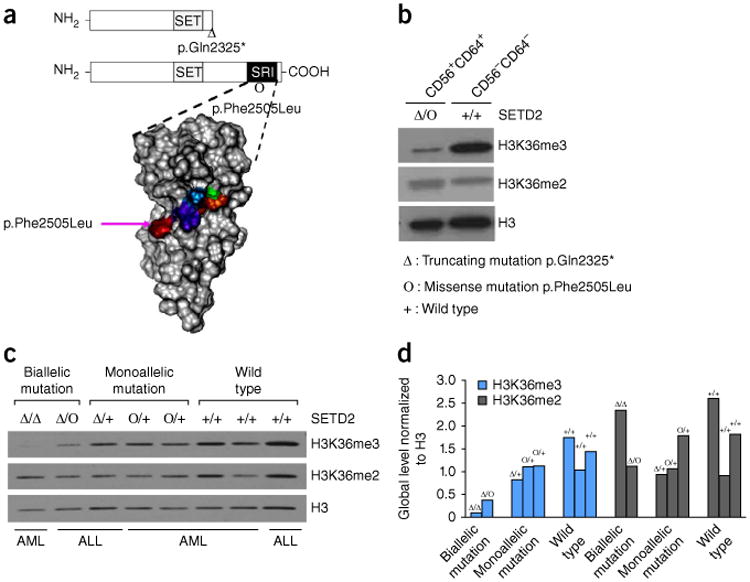

We further examined protein structural alterations of SETD2 and the associated histone methylation of H3K36 in SETD2-mutated patients. The majority (seven out of eight) of the truncating mutations in the patients resulted in loss of the C terminus SRI domain (Fig. 2a), which is responsible for the recruitment of SETD2 to its target gene locus through binding to the phosphor-C-terminal repeat domain (PCTD) of elongating RNA polymerase II (Pol II)18. Notably, in addition to a truncating mutation (NM_014159.6, c.6973C>T, p.Gln2325*; Supplementary Tables 2 and 3), the missense mutation (NM_014159.6, c.7515T>A, p.Phe2505Leu; Supplementary Tables 2 and 3) affecting the second allele of SETD2 in the twin with leukemia mapped to the surface of the SRI domain (Fig. 3a) and corresponds to a key residue that is critical for the PCTD binding of SETD2 (ref. 18). It has been shown previously that the p.Phe2505Leu alteration blocks the binding of SETD2 to the PCTD of RNA Pol II at the target gene locus18. Consistent with published data19,20, we observed a global decrease of H3K36me3 in CD56+CD64+ leukemia cells of the twin with MLL-rearranged leukemia but not in the CD56−CD64− non-leukemic cells from the same patient (Fig. 3b). Notably, additional patients with AML or ALL carrying SETD2 mutations exhibited decreased levels of global H3K36me3, with the most substantial changes observed in patients with biallelic truncating mutations (Fig. 3c,d). Therefore, loss-of-function mutations of SETD2 may impair the chromatin recruitment of SETD2 mediated by the SRI domain, which in turn contributes to the global loss of H3K36me3.

Figure 3.

H3K36me3 levels in patients with acute leukemia carrying SETD2 mutations. (a) Two SETD2 point mutations identified in the twin with leukemia. The nonsense mutation resulting in p.Gln2325* is expected to truncat the C terminus RNA Pol II–interacting SRI domain (top). The position of the missense mutation resulting in p.Phe2505Leu is also indicated. Below, surface mapping shows the five key residues (colored) located on the surface of the SRI domain that are critical for the interaction of the SRI domain with RNA Pol II18. The SRI domain of SETD2 was visualized by VMD42, and p.Phe2505Leu is marked with a pink arrow. (b) Global H3K36me3 and H3K36me2 levels in leukemic cells isolated from the twin with leukemia. The leukemic (CD56+CD64+) and normal (CD56−CD64−) cell populations were isolated from the twin with leukemia, and the SETD2 mutational status for each population is indicated. Global H3K36me3 and H3K36me2 levels were detected by western blot assays. Histone H3 was used as a loading control. (c) Global H3K36me3 and H3K36me2 levels in leukemic cells isolated from patients with either AML or ALL detected by western blot assays. The SETD2 mutational status for each patient is indicated. H3 was used as a loading control. (d) The signal intensity of each band in c was quantified by ImageJ43. The intensities of H3K36me3 and H3K36me2 were normalized to that of H3 for each lane and are shown in a bar plot. The SETD2 mutational status for each patient is indicated.

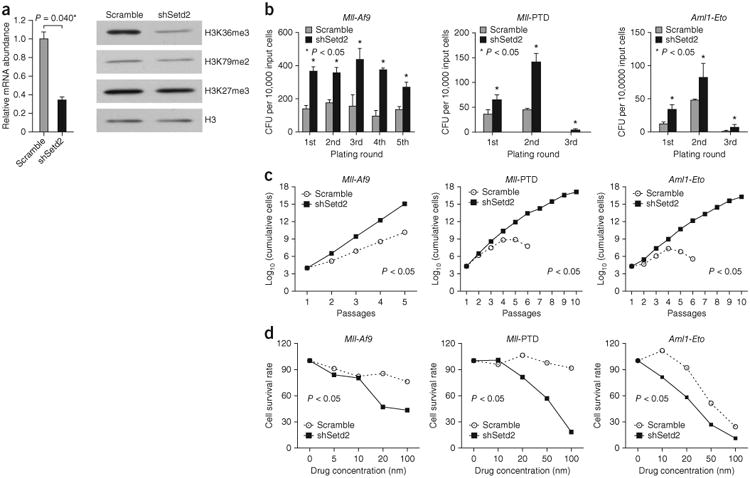

To test the functional importance of loss of function of SETD2 in the development of myeloid leukemias characterized by either MLL translocation or additional genetic aberrations identified in patients, we employed bone marrow transplantation (BMT), as well as colony-forming cell and liquid culture assays, to demonstrate the transforming effects of Setd2 knockdown in vivo and in vitro, respectively21. To determine the role of SETD2 in disease initiation, we used several established pre-leukemia knock-in mouse models, including the Mll-Af9 (also called Mllt3), Mll-PTD (partial tandem duplication) and Aml1-Eto, in which additional mutations are required to develop fullblown AML22–26. We compared the effects of Setd2 knockdown in hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells (HSPCs) derived from wild-type or knock-in mice. Transfection of Setd2 shRNA led to decreased levels of Setd2 expression and H3K36me3, whereas H3K79me2 and H3K27me3 were minimally affected in the Mll-Af9 knock-in cells (Fig. 4a and Supplementary Fig. 13). Consequently, Setd2 knockdown resulted in a significantly higher yield of total colonies in the multiple rounds of plating for Mll-Af9, Mll-PTD and Aml1-Eto knock-in HSPCs (Fig. 4b). Consistently, Setd2 knockdown equipped these pre-leukemic cells to gain a significant growth advantage over serial passaging compared to control shRNA–treated cells in liquid culture (Fig. 4c). In contrast, colony-forming cell assays showed that knockdown of Setd2 did not have a significant effect on wild-type HSPCs (Supplementary Fig. 14), suggesting an insufficient effect of Setd2 alteration alone on normal hematopoietic cell growth.

Figure 4.

Functional analysis of Setd2 in pre-leukemic cells. (a) Knockdown of Setd2 in HSPCs derived from Mll-Af9 knock-in mice. The bar plot shows the relative Setd2 expression (mean ± s.d.; n = 2 per group; Student's t test) in Mll-Af9 HSPCs transduced with Setd2 shRNA (shSetd2) or the scrambled control shRNA (scramble). The western blot shows the global levels of H3K36me3, H3K79me2 and H3K37me3 in these cells. (b) Serial colony-forming unit (CFU) re-plating assays for HSPCs derived from Mll-Af9, Mll-PTD and Aml1-Eto knock-in mice. Cells were treated with either Setd2 shRNA or the control scrambled shRNA. The plating round and the number of CFUs per 10,000 input cells are shown (mean ± s.d.; n = 3 per group; Student's t test). (c) Serial liquid culture assays for HSPCs derived from Mll-Af9, Mll-PTD and Aml1-Eto knock-in mice. Cells were treated with either Setd2 shRNA or control scrambled shRNA. The number of passages and the log10-transformed number of cumulative cells are shown (n = 5 or 10; Student's t test for comparison between two groups). (d) Increased sensitivity to mTOR inhibition by Torin1 in Setd2 knockdown HSPCs isolated from Mll-Af9, Mll-PTD and Aml1-Eto knock-in mice. Setd2 knockdown or scrambled shRNA–transduced cells were plated (n = 5; Student's t test for comparison between two groups). The mTOR inhibitor Torin1 was added at the indicated concentrations.

We applied mRNA sequencing (mRNA-seq) to further obtain the gene expression profile of the Mll-Af9 pre-leukemic cells from the first plating after Setd2 knockdown. Functional category enrichment analyses indicated that Setd2 deficiency activates gene expression in mTOR and Jak-Stat signaling pathways (Supplementary Fig. 15), which are known to contribute directly to leukemogenesis. Treatment of the Setd2 knockdown pre-leukemic cells with the mTOR small-molecule inhibitor Torin1 or with rapamycin resulted in a marked decrease in cell growth (Fig. 4d and Supplementary Fig. 16). These data suggest that Setd2 downregulation enhances the leukemogenic potential of pre-leukemic cells by activation of multiple pathways, as exemplified by the mTOR signaling pathway.

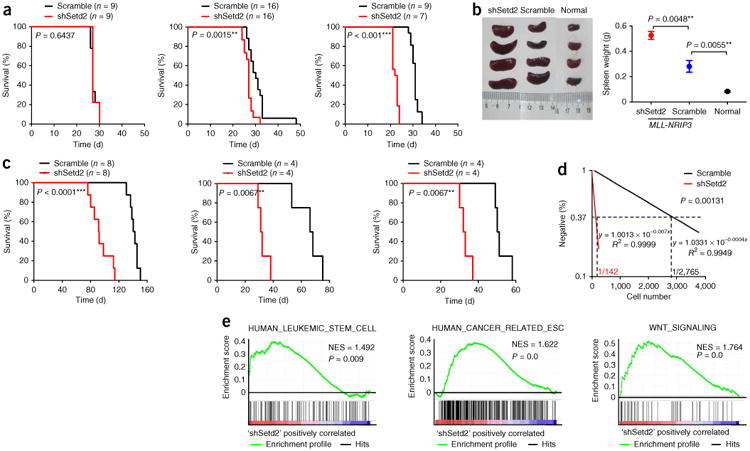

To further determine the role of Setd2 during the maintenance or progression of established leukemia, we obtained primary Mll-Af9 or MLL-NRIP3 leukemia cells from the leukemic mice (Figs. 1c and 5). Setd2 knockdown significantly accelerated the development of both Mll-Af9 and MLL-NRIP3 leukemia in the serial transfer recipients, as evidenced by shortened latency and a more severe phenotype of the leukemia (Fig. 5a–c and Supplementary Fig. 13). The limiting dilution analysis of the transplanted mice showed a significantly higher frequency of leukemia-initiating cells or leukemia stem cells (LSCs) after Setd2 knockdown (1/142 as compared to 1/2,765, P = 0.001, Fig. 5d), thereby providing direct evidence for increased self-renewal of LSCs through loss of function of Setd2. Consistently, when we examined the effect of Setd2 knockdown on MLL-rearranged leukemia cells by mRNA-seq, gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA)27 further indicated significantly higher expression of the human LSC signature28, the human cancer-related embryonic stem cell signature29,30 and the Wnt signaling pathway31,32 (Fig. 5e and Supplementary Table 8) in the Setd2 knockdown leukemia cells. These results provide strong evidence for the role of Setd2 downregulation in enhancing the stemness of LSCs, thereby contributing to the maintenance and progression of established leukemia.

Figure 5.

Functional analysis of Setd2 in leukemic cells. (a) Setd2 knockdown accelerates MLL-NRIP3 leukemia in serial BMT assays. Setd2 knockdown or scrambled shRNA–transduced MLL-NRIP3 HSPCs were transplanted into recipient mice. For secondary and tertiary BMT, an equal number of Setd2 knockdown or scrambled shRNA–transduced leukemia cells were transplanted to sublethally irradiated recipient mice. Survival curves of the leukemic mice and the associated P values are shown. (b) Hepatosplenomegaly in Setd2 knockdown MLL-NRIP3 leukemic mice. The spleens themselves (left) and their weights (right; mean ± s.d.; n = 4 per group) are shown for Setd2 knockdown MLL-NRIP3 leukemic mice, scrambled shRNA–treated MLL-NRIP3 leukemic mice and normal mice, with the associated P values indicated. (c) Setd2 knockdown accelerates Mll-Af9 leukemia in serial BMT assays. Setd2 knockdown or scrambled shRNA–transduced Mll-Af9 knock-in HSPCs were transplanted into recipient mice. For secondary and tertiary BMT, an equal number of Setd2 knockdown or scrambled shRNA–transduced leukemia cells were transplanted to sublethally irradiated recipient mice. Survival curves of leukemic mice and the associated P values are shown. (d) Limiting dilution assay. An equal number of Setd2 knockdown or scrambled shRNA–transduced Mll-Af9 knock-in leukemia cells isolated from secondary leukemias in cell dosage (as indicated in Supplementary Table 9) were transplanted to sublethally irradiated recipient mice. Leukemia-initiating cell frequencies and the P value calculated by L-calc software are shown. (e) GSEA27 plot showing increased gene expression of human leukemia stem cell28 and cancer-related embryonic stem cell (ESC)29,30 signatures, as well as Wnt signaling31,32, in MLL-NRIP3 leukemia cells with Setd2 knockdown relative to scrambled shRNA controls. The normalized enrichment score (NES) and P values are shown.

In summary, given the recent flurry of reported mutations in chromatin regulatory genes in human tumors33–39, a functional role of deregulated histone modification in cancer biology has not yet been established40. Our mutational analysis, together with in vivo and in vitro functional assays, demonstrates that loss of function of SETD2 is a critical event in facilitating both disease initiation and progression through decreased H3K36me3 in leukemias characterized by MLL fusion, MLL-PTD or AML1-ETO. Thus, a SETD2 mutation–mediated decrease of H3K36me3 may be an independent and distinct epigenetic mechanism to potentiate leukemic transformation and progression in cooperation with another genetic or epigenetic abnormality. How disruption of SETD2 cooperates with other pathogenic mechanisms, especially in promoting the stemness of LSCs, certainly warrants further investigations. Nonetheless, the existence of SETD2 mutations in a range of hematopoietic malignancies as well as non-hematopoietic malignancies suggests that the SETD2-H3K36me3 pathway may be a common tumor-suppressive mechanism for cancer, thereby offering a new opportunity for the development of cancer diagnostics and therapeutics.

Online Methods

Sample description and preparation of the monozygotic twin pair

A detailed case report is included in the Supplementary Note. In brief, a 3-year-old case was diagnosed as having AML FAB-M5 with MLL translocation on the basis of her clinical presentation, blood counts, morphology, FISH and cytometry analysis (Supplementary Fig. 1). The twin with MLL-rearranged leukemia (PT) and her healthy twin sibling (HT) were monozygotic twins, which was confirmed by a birth record from the hospital, genotyping of short tandem repeat (STR) loci and Amelogenin loci and STR-PCR analysis (Supplementary Fig. 2). FISH analysis did not detect MLL translocation in HT. According to the regulations of the institutional ethics review boards from the Institute of Hematology and Blood Diseases Hospital, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences and Peking Union Medical College, informed consent was signed by the parents of the twins.

CD56+CD64+ leukemia cells (PT_Leukemia), CD56−CD64− normal cells (PT_Normal) and normal PBMCs from HT were used for WGS and mRNA-seq. Sequencing was performed at the Core Genomic Facility of Beijing Institute of Genomics, Chinese Academy of Sciences. Genomic DNA libraries with a 1.5-kb insert size were prepared using genomic DNA extracted from PT_Leukemia and HT, followed by SOLiD mate-pair sequencing (50 × 2 bp). Three mRNA libraries with a 400-bp insert size were prepared using RNA harvested from PT_Leukemia, PT_Normal and HT, followed by paired-end sequencing (81 × 2 bp). All data were aligned to hg19 with Bioscope 1.3 (https://products.appliedbiosystems.com/ab/en/US/adirect/ab?cmd=catNavigate2&catID=606802&tab=Overview) and BWA44, as summarized in Supplementary Table 1.

Detection of somatic mutations

We applied a series of in-house softwares to detect point mutations and structural variations on a whole-genome scale combining WGS and mRNA-seq data. In total, 623 SNVs (including 9 nonsynonymous SNVs and 1 splice-site SNV), 41 small indels, 3 large heterozygous deletions and 2 fusion genes were identified (a global view of all the genomic variations detected is shown in Fig. 1a and Supplementary Fig. 3, the 10 validated SNVs are presented in Supplementary Table 2 and Supplementary Fig. 8, all 623 SNVs and 41 small indels are shown in Supplementary Table 10, 3 large deletions are shown in Supplementary Fig. 6 and 2 validated fusion genes are shown in Supplementary Figs. 4 and 7).

Point variation (SNV and small indel) detection

Candidate SNVs were identified by CASpoint (an in-house software), which calculated the somatic score and two significance levels: one is calculated by one-side Fisher testing, which calculated the statistical significance in which the tumor mutant allele frequency (MAF) is higher than the MAF in the normal cell population; and the second uses binomial testing, which calculated the significance of the tumor mutant allele number observed from the aligned tumor sequencing data, where the data meet a binomial distribution. Putative SNVs were identified using the following filtering criteria: (i) somatic score greater than 35; (ii) Fisher exact test (one tailed) P value for the mutant frequency between the tumor and normal tissue of less than 0.05; (iii) binomial test P value for the tumor alleles of less than 1 × 10−15; (iv) tumor mutant allele number of at least 5; (v) Phred quality of the start point of the tumor covering the locus point larger than 1; (vi) tumor MAF greater than 0.2; and (vii) for a normal sample, a base quality of the reference allele larger than 30 and mapping quality of the reference allele larger than 35, and for a tumor sample, a base quality of the non-reference allele larger than 30 and mapping quality of the non-reference allele larger than 35. All filtering parameters were obtained from other in-house cancer projects.

We used SaMtools45 to identify cancer-specific small indels. We set the total depth of one indel breakpoint to be at least 20 and the supporting reads rate to greater than 0.3 for the tumor sample and equal to 0 for the normal sample. After annotation, we found 41 leukemia-specific small indels, including 38 in intron and intergenic regions and 3 in UTRs.

Structural variation (CNV and fusion gene) detection

CAScnv (an in-house software) was used for detecting the somatic DNA CNV. We computed the number of reads aligned by Bioscope in the non-overlapping minimum sliding window (MSW), whose size is derived from CNV-seq46. We used the circular binary segmentation algorithm (CBS47) to segment CNV regions according to logarithm reads ratio (LRR)

where RC and RN are read counts of cancer and normal DNA in each non-overlapping sliding window (1,500 MSWs as a sliding window) separately, and γ is the correction coefficient, which is the ratio of the read counts of normal and cancer DNA in a chromosome. From the above method, we divided the genome into contiguous regions according to the segmentation significance level (P < 1 × 10−5). We detected three large heterozygous deletions, one in chromosome 6 and two in chromosome 7, and validated them by genotyping loss of heterozygosity (LOH) sites predicted from the WGS data (Supplementary Fig. 6).

Candidate leukemia-specific gene fusion events were identified by CASfus (an in-house software), which is used for detecting interchromosomal or intra-chromosomal gene fusions from genome sequencing data. CASfus locates fusion candidate regions from inappropriate read pairs aligned in different gene loci according to annotation, assembles all the reads around these regions into contigs and then realigns them to detect potential fusion events. CASbreak (an in-house software) was used to detect cancer-specific breakpoints. We detected two leukemia-specific fusion events, MLL-NRIP3 and NF1-AARSD1, from WGS data by crossvalidation with CASfus and CASbreak and verified them with mRNA-seq and PCR sequencing (Fig. 1b, Supplementary Note, Supplementary Table 11 and Supplementary Figs. 4 and 7).

SETD2 mutation screening in patients with acute leukemia using targeted sequencing

To determine the recurrence of SETD2 mutations, we collected 134 patients with AML and 107 patients with ALL (Supplementary Note). According to the regulations of the institutional ethics review boards from the Institute of Hematology and Blood Diseases Hospital, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences and Peking Union Medical College, TongJi Hospital, TongJi Medical College, HuaZhong University of Science and Technology and Changhai Hospital, Second Military Medical University, informed consent was signed by the parents or guardians of the patients. We amplified all 21 exons of SETD2 with a set of PCR primers designed by Primer 5.0 with the default parameters (Supplementary Table 12) and performed Sanger sequencing on PCR amplicons from the 241 leukemia samples. After eliminating known polymorphisms reported in the dbSNP database (build 131)48, the Korean genome49, the YanHuang database50, the 1000 human genome polymorphism data set51 (1000 Genomes) and the Exome Variant Server (http://evs.gs.washington.edu/EVS/), we obtained candidate somatic mutations. We further confirmed somatic mutations if they were present in tumor cells but were undetectable in any available matched normal control cells (skin, saliva, mesenchymal stem cells or remission PBMCs) by PCR sequencing. When matched normal control tissues were not available, the candidate variants were classified as very probable somatic mutations if they were not among the 146 SETD2 polymorphisms found in 950 normal individuals (257 Asian and 693 non-Asian) in the collected data sets. Clinical and mutational information for the patients with leukemia is summarized in Supplementary Tables 3–6.

SETD2 deletion detection based on gene expression array data

To determine the deletion pattern across SETD2, we used an established genomic method13,14 to analyze large deletions in seven gene expression data sets consisting of individuals with AML or ALL and normal individuals by global gene expression meta-analysis. In brief, we compared the gene expression profile of each individual to a reference baseline made up of a large number of highly similar samples. For each sample, the expression value of each gene was divided by the median expression value of the same gene across the entire data set. A detailed description of the method can be found in the studies of Mayshar et al.13,14. First, we validated the methodology for inferring large deletions based on transcriptional profiling using deletions detected by SNP array in a cohort of patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia, in which both SNP and gene expression analyses had been conducted52 (Supplementary Fig. 17). Second, we used a cohort of patients with ccRCC15 with SNP array and expression array data to test the power of detecting large deletions across the SETD2 genomic region (chromosome 3p) with the expression array. The results demonstrated that the expression analysis detected chromosome 3p deletion at a similar frequency as that identified by the SNP array data (Supplementary Fig. 12). Third, using the same genomic analysis method, large genomic deletions encompassing SETD2 were detected in patients with MLL fusion, as well as patients with either TEL-AML1 or BCR-ABL, but at a very low frequency (≤0.6%) (Supplementary Fig. 11 and Supplementary Table 7).

Confirming rare deletion across SETD2 using LOH detection in chromosome 3p

To further confirm the rare SETD2 deletion pattern obtained from the expression-based genomic analysis described above, we used the MassARRAY system (Sequenom) to detect LOH of chromosome 3p in our cohort of patients with acute leukemia. Sequenom genotyping has been used to detect LOH across known tumor-suppressor genes, especially for chromosome 3p53–55, as a locus is very likely to have LOH if it contains continuous homozygous SNPs. Each SNP is defined as homozygous or heterozygous on the basis of Sequenom genotyping. In total, we selected 69 SNPs (63 on chromosome 3 and 6 on other chromosomes) with MAFs ranging from 0.3 to 0.7 in the 1000 Genomes data. Thirty-five out of 47 SNPs located on chromosome 3p are within the SETD2 locus. On average, these 63 sites on chromosome 3 space about 1 kb and 4 Mb within and outside the SETD2 locus, respectively. Amplification and extension primers for Sequenom genotyping were designed using Human GenoTyping Tools on the MySequenom website (https://www.mysequenom.com/) and MassARRAY Assay Design v3.1 software.

On the basis of targeted sequencing of SETD2 in the 241 patients with leukemia, 69 patients without any heterozygous SNPs in exonic regions of SETD2 were selected as candidates for LOH screening. We also selected 19 negative controls with multiple (≥5) heterozygous SNPs in exonic regions of SETD2. We genotyped all 69 selected SNPs for 30 out of 69 SETD2 LOH candidates and 10 out of 19 negative controls according to the Sequenom standard protocol. Genotype calls were automatically generated according to signal characteristics56. Results were then linked to plate information created by MassARRAY Typer 4.0 software. Individual calls and their MAFs were manually reviewed and finalized.

We further selected all 254 Asians from the 1000 Genomes data as a control set to test whether the amount of SETD2 LOH in the leukemia cohort is significantly different from that of the healthy population. We extracted MAFs from the 1000 Genomes data for 18 SNPs identified by targeted sequencing of SETD2 and 69 SNPs used in the genotyping for detecting chromosome 3 LOH. A similar pattern of LOH in SETD2 was observed between the leukemia cohort and the healthy Asian population. Then, using neutral LOH testing, we concluded that the same frequency (26-29%) of LOH across SETD2 is due to linkage disequilibrium (http://hapmap.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/cgi-perl/gbrowse/hapmap24_B36/#search) rather than deletion in the SETD2 locus (Supplementary Fig. 10a). This finding is consistent with the rare SETD2 deletion detected by large-scale expression genomic analysis (Supplementary Fig. 11 and Supplementary Table 7).

DNA methylation analysis of the SETD2 promoter

To examine whether the SETD2 promoter is hypermethylated in patients with acute leukemia, we obtained available Human DNA Methylation450 array data of 194 AML and 301 ccRCC samples from TCGA (https://tcga-data.nci.nih.gov/tcga/tcgaHome2.jsp). We used the level 3 methylation data defined by TCGA, which is the ratio of the intensity of the methylated probe to the total intensity of the methylated and unmethylated probes for each CpG site. Therefore, a β value ranges between 0 (least methylated) and 1 (most methylated), which represents the degree of methylated state of any particular locus. The data contain null entries, which correspond to probes that overlap with known SNPs or other genomic variations and probes whose signal intensities are lower than the background. For each gene, we defined its promoter as the region starting 5 kb upstream and ending 1 kb downstream of the annotated transcription start site based on UCSC gene annotations (release on April 8, 2013). We filtered out probes with many null entries (i.e., number of null entries over 1% of the sample size) and those located outside of gene promoters. 196,896 CpG probes remained for further analysis. The β values of all CpG sites located in each promoter were averaged as the DNA methylation level of this promoter. Promoter DNA methylation of all genes in 194 patients with AML were examined (Supplementary Fig. 10d). We also visualized the DNA methylation levels of SETD2, BAP1, KDM6A, PBRM1, PDZD2 and TP73 in patients with AML or ccRCC (Supplementary Fig. 10e). Among these genes, SETD2, BAP1, KDM6A and PBRM1 are known to be unmethylated in patients with ccRCC57, and FDZD2 and TP73 have been shown to be hypermethylated in patients with hematopoietic malignancies58,59.

Mutational pattern analysis of cancer-causative genes and SETD2

The gene-truncating mutation rate (FT) is the ratio of the number of patients with truncating mutations in a certain gene to the number of patients with non-synonymous or frameshift small indel (coding) mutations in that gene. The gene multi-hit rate (FMH) is the ratio of the number of patients with at least one truncating mutation and one other coding mutation of a certain gene to the number of patients with coding mutations in that gene. We calculated the FT and FMH of cancer-causative genes using mutations in the COSMIC database (release 65). For SETD2, we calculated FT and FMH using mutations in the COSMIC data set combined with data sets provided by Zhang et al.39 and data sets from this study. The results for all genes analyzed are shown in Supplementary Table 13.

Plasmid, cell transfection and lentivirus transduction

The SF-LV-shRNA-GFP and SF-LV-shRNA-BFP plasmids were obtained from K.L. Rudolph's lab60, scrambled shRNA was cloned from TRIPZ non-silencing shRNA (Open Biosystems, RHS4743) and Setd2 shRNAs were cloned from GIPZ mouse Setd2 shRNA (Open Biosystems, RMM4532). Lentiviruses (SF-LV-scramble-GFP and SF-LV-shSetd2-GFP) were generated by co-transfecting the packaging plasmids sPAX2 and MD2.G into 293T cells by Fugene 6 (Promega, E2691). The MLL-NRIP3 fusion gene was subcloned into the pMIG-IRES-GFP vector. For viral production, the pMIG-MLL-NRIP3 or empty control vector was co-transfected into the 293T packaging cell line with pCMV-VSVG and pKat. The lentivirus supernatants were collected 42 h after transfection, filtered through a 0.45-μm filter and used immediately to infect overnight-cultured bone marrow (BM) cells.

Colony-forming assay

One milliliter of colony assay medium (MethoCult GF M3434, Stem Cell Technologies) contained 1 × 104 GFP+ cells, which were sorted from mouse BM cells infected with lentiviruses. The cells were plated in 35-mm dishes (Nunc). Each sample was plated in triplicate. Colony counts were scored, and re-platings occurred every 7 d.

In vitro long-term liquid culture

Knock-in mouse BM cells were harvested and infected with lentiviruses. 1 × 104 or 2 × 104 GFP+ cells were sorted and cultured in Iscove's modified Dulbecco's medium (IMDM) with 10% FBS and cytokines (SCF, GM-CSF, IL-3 and IL-6), and each sample was plated in duplicate wells. Cell counts and passages were repeated every 7 d.

Inhibitor treatment experiment

Knock-in mouse BM cells were harvested and infected with lentiviruses. 1 × 104 GFP+ cells were sorted and cultured in IMDM with 10% FBS and cytokines (SCF, GM-CSF, IL-3 and IL-6) and various concentrations of inhibitors in a 24-well plate, and each sample was plated in duplicate. Cumulative cells were counted 48 h after drug treatment.

Mouse and BMT assay

Animals were housed in the animal barrier facility at Cincinnati Children's Hospital Medical Center or the Institute of Hematology, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences. All animal studies were conducted according to an approved Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee protocol at both institutions. Randomized C57BL/6J mice with aged 2–4 months were used, and experimenters that harvested mice for BMT were double blinded. Mycoplasma contamination was always negative using regular examination.

Mll-Af9 (ref. 22), Mll-PTD23 or Aml1-Eto24 knock-in mice were injected with 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) (150 mg per kg body weight), and BM cells were harvested 4 d after injection. Mononuclear cells were isolated by density gradient centrifugation. BMTs were performed as described61. Briefly, lethally or sublethally irradiated recipients were reconstituted with Setd2 shRNA–infected BM cells or Mll-Af9 leukemic cells. Secondary or tertiary transplantations were performed with GFP+ BM cells sorted from the first or secondary transplantation recipients when they became morbid. Female and male mice were used for recipients and donors, respectively.

MLL-NRIP3 AML was generated by injection of MLL-NRIP3–transduced BM cells into lethally irradiated syngeneic recipient mice. Primary MLL-NRIP3 leukemia cells were transduced with SF-LV-shSetd2-BFP lentiviruses or SF-LV-scramble-BFP lentiviruses. GFP and BFP double-positive cells were sorted and injected into sublethally irradiated recipients. Serial transplantation was performed to determine the self-renewal potential of the established leukemia cells. Almost all of the mice used for serial BMT were female.

Limited dilution assay

GFP+ Mll-Af9 knock-in BM cells were sorted from the primary transplantation recipients when they became morbid. 250,000 CD45.1+ helper cells mixed with 100,000, 10,000, 1,000 or 100 GFP+ BM cells were injected to lethally irradiated CD45.1 congenic recipient mice (Supplementary Table 9).

Western blot (WB) analysis

PBMCs from the cohort of patients with leukemia and GFP+-sorted Mll-Af9 knock-in BM cells were used for WB analysis. One million cells were lysed with 50 μl 2× SDS sample buffer, sonicated for 20 s and then boiled at 95 °C for 5 min. These whole-cell extractions were resolved by SDS-PAGE and electrotransferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes (Millipore). The following primary antibodies were used in this study: anti-SETD2 (Aviva, ARP47617_T100, 1:500), anti-H3 (Abcam, ab1791, 1:30,000), anti-H3K36me3 (Abcam, ab9050, 1:4,000), anti-H3K79me2 (Abcam, ab3594, 1:1,000) and anti-H3K27me3 (Abcam, ab6002, 1:1,000). Horseradish peroxidase–conjugated antibodies to rabbit (GE, NA934V, 1:6,000) were used as the secondary antibody, and SuperSignal West Dura Chemiluminescent Substrate (Pierce) was used for detection.

mRNA expression analysis

mRNA-seq was performed to profile mRNA expression levels in Setd2 knockdown HSPCs and scrambled control HSPCs from the first plating in the Mll-Af9 knock-in mouse model and from the serial BMT MLL-NRIP3 mouse model. Setd2 knockdown with two different shRNAs was performed for each HSPC from the Mll-Af9 knock-in mouse model or MLL-NRIP3 mouse model. mRNA-seq reads were aligned to the mm9 reference sequence using BWA44 or TopHat62 algorithms with a tolerance of three mismatches. Then we used Cuffdiff62 to perform differential expression testing to detect the differentially expressed genes. Genes with q < 0.05 were defined to be statistically differentially expressed. Then the differentially expressed genes identified were used for pathway enrichment analysis with DAVID Bioinformatics resources63. Gene lists, including KEGG pathway signatures and stem cell signatures, were obtained from the GSEA27 MSigDB website (http://www.broadinstitute.org/gsea/msigdb/index.jsp) for GSEA analysis in our mRNA expression data.

Statistical analyses and data visualization

All statistical tests were performed using GraphPad Prism 5 and the R statistical software package. Survival curves were compared using GraphPad Prism 5 by Kaplan-Meier analysis followed by log-rank (Mantel-Cox) test comparison. Statistical comparisons between two groups (Setd2 knockdown compared to scrambled control) were performed in GraphPad Prism 5 using an unpaired, two-tailed Student's t test; equal variances were not assumed. Data were visualized by using GraphPad Prism 5, Microsoft Visio 2007, Microsoft Excel, Microsoft PowerPoint and the R statistical software package.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was performed with the support of the Core Genomic Facility of Beijing Institute of Genomics, Chinese Academy of Sciences. We thank L. Cheng, L. Zhang, C.-I. Wu and X. Lu for their critical reading and valuable comments on the manuscript. We also thank T.R. Bartell for English editing. This study was supported by China Ministry of Science and Technology grants 2011CB964801 (to T.C.), 2012CB966600 (to W.Y. and X.Z.), 2010DFB30270 (to T.C.) and 2014CB542001 (to Q.-f.W.), National Natural Science Foundation of China grants 81090411 (to T.C.), 81130074 (to W.Y.), 30825017 (to T.C.), 81000220 (to F.H.), 81070442 (to Q.-f.W.) and 91331111 (to Q.-f.W.), the Hundred Talents Program of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (to Q.-f.W.), Tianjin Municipal Science and Technology Commission grant 09ZCZDSF03800 (to T.C.), the ‘Strategic Priority Research Program’ of the Chinese Academy of Sciences XDA01010305 (to Q.-f.W.), the ‘Knowledge Innovation Program’ of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (to F.H.) and a Pilot Research Grant of the State Key Laboratory of Experimental Hematology (to Q.-f.W. and G.H.). T.C. was a recipient of the Scholar Award from the Leukemia and Lymphoma Society (1027-08).

Footnotes

Accession codes: All mRNA-seq data are deposited at NCBI Sequence Read Archive (SRA) database under accession code SRA123673.

Note: Any Supplementary Information and Source Data files are available in the online version of the paper.

Author Contributions: X.Z. and H.Z. performed and directed clinical analyses of the study. F.H. and S.L. performed sequencing and statistical analyses and contributed to manuscript writing. A.C. performed in vitro experiments and mouse studies. Y.W., X. Yan, W.W., Y.P., H.C., C.H., Y. Zhang, X. Yang, J.Y., Jing Zhou, Lixia Zhang, S.M., X.W., Li Zhang, Y. Zou and Y.C. contributed to in vitro experiments and mouse studies. W.Y., X. Lu, X. Liu, L.C., L.H., L.D., W.Z., J. Wu, X. Li and S.Z. contributed to data analyses. Jianxiang Wang, Jianfeng Zhou, Z.G. and Jianmin Wang provided clinical samples. T.C., Q.-f.W. and G.H. conceived and directed the study and wrote the manuscript.

Competing Financial Interests: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.Krivtsov AV, Armstrong SA. MLL translocations, histone modifications and leukaemia stem-cell development. Nat Rev Cancer. 2007;7:823–833. doi: 10.1038/nrc2253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network. Genomic and epigenomic landscapes of adult de novo acute myeloid leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:2059–2074. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1301689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Balgobind BV, et al. NRIP3: a novel translocation partner of MLL detected in a pediatric acute myeloid leukemia with complex chromosome 11 rearrangements. Haematologica. 2009;94:1033. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2008.004564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sun XJ, et al. Identification and characterization of a novel human histone H3 lysine 36–specific methyltransferase. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:35261–35271. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M504012200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhang Y, Rowley JD. Chromatin structural elements and chromosomal translocations in leukemia. DNA Repair (Amst) 2006;5:1282–1297. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2006.05.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhang Y, et al. The role of mechanistic factors in promoting chromosomal translocations found in lymphoid and other cancers. Adv Immunol. 2010;106:93–133. doi: 10.1016/S0065-2776(10)06004-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mitelman F, Johansson B, Mertens F. The impact of translocations and gene fusions on cancer causation. Nat Rev Cancer. 2007;7:233–245. doi: 10.1038/nrc2091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Balgobind BV, Zwaan CM, Pieters R, Van den Heuvel-Eibrink MM. The heterogeneity of pediatric MLL-rearranged acute myeloid leukemia. Leukemia. 2011;25:1239–1248. doi: 10.1038/leu.2011.90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Greaves MF, Wiemels J. Origins of chromosome translocations in childhood leukaemia. Nat Rev Cancer. 2003;3:639–649. doi: 10.1038/nrc1164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Edmunds JW, Mahadevan LC, Clayton AL. Dynamic histone H3 methylation during gene induction: HYPB/Setd2 mediates all H3K36 trimethylation. EMBO J. 2008;27:406–420. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Berger SL. The complex language of chromatin regulation during transcription. Nature. 2007;447:407–412. doi: 10.1038/nature05915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liu H, Xing Y, Yang S, Tian D. Remarkable difference of somatic mutation patterns between oncogenes and tumor suppressor genes. Oncol Rep. 2011;26:1539–1546. doi: 10.3892/or.2011.1443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mayshar Y, et al. Identification and classification of chromosomal aberrations in human induced pluripotent stem cells. Cell Stem Cell. 2010;7:521–531. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2010.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ben-David U, Mayshar Y, Benvenisty N. Large-scale analysis reveals acquisition of lineage-specific chromosomal aberrations in human adult stem cells. Cell Stem Cell. 2011;9:97–102. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2011.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dondeti VR, et al. Integrative genomic analyses of sporadic clear cell renal cell carcinoma define disease subtypes and potential new therapeutic targets. Cancer Res. 2012;72:112–121. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-1698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network. Comprehensive molecular characterization of clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Nature. 2013;499:43–49. doi: 10.1038/nature12222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rhodes DR, et al. Oncomine 3.0: genes, pathways, and networks in a collection of 18,000 cancer gene expression profles. Neoplasia. 2007;9:166–180. doi: 10.1593/neo.07112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li M, et al. Solution structure of the Set2-Rpb1 interacting domain of human Set2 and its interaction with the hyperphosphorylated C-terminal domain of Rpb1. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:17636–17641. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506350102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Duns G, et al. Histone methyltransferase gene SETD2 is a novel tumor suppressor gene in clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Cancer Res. 2010;70:4287–4291. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-0120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fontebasso AM, et al. Mutations in SETD2 and genes affecting histone H3K36 methylation target hemispheric high-grade gliomas. Acta Neuropathol. 2013;125:659–669. doi: 10.1007/s00401-013-1095-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fontebasso AM, et al. Mutations in SETD2 and genes affecting histone H3K36 methylation target hemispheric high-grade gliomas. Acta Neuropathol. 2009;125:659–487. doi: 10.1007/s00401-013-1095-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Corral J, et al. An Mll-AF9 fusion gene made by homologous recombination causes acute leukemia in chimeric mice: a method to create fusion oncogenes. Cell. 1996;85:853–861. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81269-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dorrance AM, et al. Mll partial tandem duplication induces aberrant Hox expression in vivo via specific epigenetic alterations. J Clin Invest. 2006;116:2707–2716. doi: 10.1172/JCI25546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Higuchi M, et al. Expression of a conditional AML1-ETO oncogene bypasses embryonic lethality and establishes a murine model of human t(8;21) acute myeloid leukemia. Cancer Cell. 2002;1:63–74. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(02)00016-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zorko NA, et al. Mll partial tandem duplication and Flt3 internal tandem duplication in a double knock-in mouse recapitulates features of counterpart human acute myeloid leukemias. Blood. 2012;120:1130–1136. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-03-415067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Grisolano JL, O'Neal J, Cain J, Tomasson MH. An activated receptor tyrosine kinase, TEL/PDGFβR, cooperates with AML1/ETO to induce acute myeloid leukemia in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:9506–9511. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1531730100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Subramanian A, et al. Gene set enrichment analysis: a knowledge-based approach for interpreting genome-wide expression profiles. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:15545–15550. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506580102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gal H, et al. Gene expression profiles of AML derived stem cells; similarity to hematopoietic stem cells. Leukemia. 2006;20:2147–2154. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2404401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wong DJ, et al. Module map of stem cell genes guides creation of epithelial cancer stem cells. Cell Stem Cell. 2008;2:333–344. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2008.02.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang Y, Armstrong SA. Cancer: inappropriate expression of stem cell programs? Cell Stem Cell. 2008;2:297–299. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2008.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang Y, et al. The Wnt/β-catenin pathway is required for the development of leukemia stem cells in AML. Science. 2010;327:1650–1653. doi: 10.1126/science.1186624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kanehisa M, Goto S, Sato Y, Furumichi M, Tanabe M. KEGG for integration and interpretation of large-scale molecular data sets. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:D109–D114. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gerlinger M, et al. Intratumor heterogeneity and branched evolution revealed by multiregion sequencing. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:883–892. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1113205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gui Y, et al. Frequent mutations of chromatin remodeling genes in transitional cell carcinoma of the bladder. Nat Genet. 2011;43:875–878. doi: 10.1038/ng.907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Varela I, et al. Exome sequencing identifies frequent mutation of the SWI/SNF complex gene PBRM1 in renal carcinoma. Nature. 2011;469:539–542. doi: 10.1038/nature09639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dalgliesh GL, et al. Systematic sequencing of renal carcinoma reveals inactivation of histone modifying genes. Nature. 2010;463:360–363. doi: 10.1038/nature08672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zang ZJ, et al. Exome sequencing of gastric adenocarcinoma identifies recurrent somatic mutations in cell adhesion and chromatin remodeling genes. Nat Genet. 2012;44:570–574. doi: 10.1038/ng.2246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fujimoto A, et al. Whole-genome sequencing of liver cancers identifies etiological influences on mutation patterns and recurrent mutations in chromatin regulators. Nat Genet. 2012;44:760–764. doi: 10.1038/ng.2291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhang J, et al. The genetic basis of early T-cell precursor acute lymphoblastic leukaemia. Nature. 2012;481:157–163. doi: 10.1038/nature10725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ryan RJ, Bernstein BE. Molecular biology. Genetic events that shape the cancer epigenome. Science. 2012;336:1513–1514. doi: 10.1126/science.1223730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Krzywinski M, et al. Circos: an information aesthetic for comparative genomics. Genome Res. 2009;19:1639–1645. doi: 10.1101/gr.092759.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Humphrey W, Dalke A, Schulten K. VMD: visual molecular dynamics. J Mol Graph. 1996;14:33–38. doi: 10.1016/0263-7855(96)00018-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Schneider CA, Rasband WS, Eliceiri KW. NIH Image to ImageJ: 25 years of image analysis. Nat Methods. 2012;9:671–675. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Li H, Durbin R. Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:1754–1760. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Li H, et al. The Sequence Alignment/Map format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:2078–2079. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Xie C, Tammi MT. CNV-seq, a new method to detect copy number variation using high-throughput sequencing. BMC Bioinformatics. 2009;10:80. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-10-80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Olshen AB, Venkatraman ES, Lucito R, Wigler M. Circular binary segmentation for the analysis of array-based DNA copy number data. Biostatistics. 2004;5:557–572. doi: 10.1093/biostatistics/kxh008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sherry ST, et al. dbSNP: the NCBI database of genetic variation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001;29:308–311. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.1.308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ahn SM, et al. The first Korean genome sequence and analysis: full genome sequencing for a socio-ethnic group. Genome Res. 2009;19:1622–1629. doi: 10.1101/gr.092197.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Li G, et al. The YH database: the first Asian diploid genome database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:D1025–D1028. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Abecasis GR, et al. A map of human genome variation from population-scale sequencing. Nature. 2010;467:1061–1073. doi: 10.1038/nature09534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mosca L, et al. Integrative genomics analyses reveal molecularly distinct subgroups of B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia patients with 13q14 deletion. Clin Cancer Res. 2010;16:5641–5653. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-0151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tai AL, et al. High-throughput loss-of-heterozygosity study of chromosome 3p in lung cancer using single-nucleotide polymorphism markers. Cancer Res. 2006;66:4133–4138. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-2775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Onken MD, et al. Loss of heterozygosity of chromosome 3 detected with single nucleotide polymorphisms is superior to monosomy 3 for predicting metastasis in uveal melanoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:2923–2927. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-2383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Angeloni D. Molecular analysis of deletions in human chromosome 3p21 and the role of resident cancer genes in disease. Brief Funct Genomic Proteomic. 2007;6:19–39. doi: 10.1093/bfgp/elm007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Arcila M, Lau C, Nafa K, Ladanyi M. Detection of KRAS and BRAF mutations in colorectal carcinoma roles for high-sensitivity locked nucleic acid–PCR sequencing and broad-spectrum mass spectrometry genotyping. J Mol Diagn. 2011;13:64–73. doi: 10.1016/j.jmoldx.2010.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ibragimova I, Maradeo ME, Dulaimi E, Cairns P. Aberrant promoter hypermethylation of PBRM1, BAP1, SETD2, KDM6A and other chromatin-modifying genes is absent or rare in clear cell RCC. Epigenetics. 2013;8:486–493. doi: 10.4161/epi.24552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Figueroa ME, et al. DNA methylation signatures identify biologically distinct subtypes in acute myeloid leukemia. Cancer Cell. 2010;17:13–27. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2009.11.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zhao Y, et al. Aberration of p73 promoter methylation in de novo myelodysplastic syndrome. Hematology. 2012;17:275–282. doi: 10.1179/1607845412Y.0000000018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wang J, et al. A differentiation checkpoint limits hematopoietic stem cell self-renewal in response to DNA damage. Cell. 2012;148:1001–1014. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.01.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zhang Y, et al. Stress hematopoiesis reveals abnormal control of self-renewal, lineage bias, and myeloid differentiation in Mll partial tandem duplication (Mll-PTD) hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells. Blood. 2012;120:1118–1129. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-02-412379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Trapnell C, et al. Differential gene and transcript expression analysis of RNA-seq experiments with TopHat and Cufflinks. Nat Protoc. 2012;7:562–578. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2012.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Huang W, Sherman BT, Lempicki RA. Systematic and integrative analysis of large gene lists using DAVID bioinformatics resources. Nat Protoc. 2009;4:44–57. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2008.211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.