Abstract

Molecular profiling of central nervous system lymphomas in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) samples can be challenging due to the paucicellular and limited nature of the samples. Presented herein is a microfluidic platform for complete CSF lymphoid cell analysis, including single cell capture in sub-nanoliter traps, and molecular and chemotherapeutic response profiling via on-chip imaging, all in less than one hour. The system can detect scant lymphoma cells and quantitate their kappa/lambda immunoglobulin light chain restriction patterns. The approach can be further customized for measurement of additional biomarkers, such as those for differential diagnosis of lymphoma subtypes or for prognosis, as well as for imaging exposure to experimental drugs.

Keywords: lymphoma, microfluidics, point-of-care, cerebrospinal fluid, drug testing

Introduction

Central nervous system (CNS) lymphoma is diagnosed in about 5,000 new patients per year in the US and is either primary (de novo lymphoma) or secondary (metastases from systemic disease). Primary CNS lymphoma (PCNSL) accounts for ~1,500-3,000 patients in the US, but affects an estimated 2-6% of all AIDS patients and is thus more prevalent in low/middle income countries with high AIDS frequency 1,2. With respect to secondary lymphoma, 5% of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL), up to 25% of mantle cell lymphoma patients, and up to 50% of Burkitt lymphoma patients will ultimately exhibit CNS involvement 3-6. Importantly, secondary CNS lymphoma is often the cause of death in high-grade lymphomas unresponsive to treatment 7. The diagnosis of CNS lymphoma typically relies on conventional cytology of CSF or radiographic means (MRI). More recently the use of flow cytometry and PCR specific for immunoglobulin heavy chain have improved the ability to detect minimal lymphoma involvement. Recent molecular distinctions have been made between germinal (GCB) type DLBCL, activated (ABC) type DLBCL, and DLBCL driven by translocations or over expression of c-Myc and BCL-2. Prognosis and treatment choices have been shown to depend on these distinctions, highlighting the need for a diagnostic platform that can support molecular phenotyping 8-12.

Lumbar puncture is used to collect small volumes of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF; up to 3 mL per patient). CSF has a viscosity similar to water and contains distinct electrolytes, but also contains scant cells 13. In normal individuals, 1 mL of CSF contains 150-2,000 T lymphocytes, 80-1,100 monocytes, and 0-30 B lymphocytes, as well as other less common cell populations 14,15. In patients with CNS lymphoma, lymphocyte populations increase in number and are monoclonal. (See Supplementary Material: Table S1 for cell counts and cell differentials typically seen in cases of CNS lymphoma compared with normal ranges.) Conventional cytology (smear test) is most useful when lymphoma cells make up >5% of cells in a sample of CSF, and can be difficult to interpret due to similar morphology between benign and malignant lymphocytes 16. Flow cytometry has shown impressive sensitivity, but requires sufficient numbers of cells for analysis 15,17.

To address these unmet needs in the diagnosis and characterization of CNS lymphoma, we developed a microfluidic chip that allows analysis of all harvested cells (i.e. without the need for sample preparation which often loses cells and/or alters them) and which could potentially be used in resource limited settings where HIV is prevalent. Based on previous designs of chips incorporating individual cell capture/analysis 18-20, we implemented a new integrated device that allows comprehensive staining, phenotyping, and drug response measurements of lymphoma cells. We expect that this approach will provide a flexible platform to profile cancer cells from paucicellular samples, thus enhancing the accuracy and ease of CNS lymphoma diagnosis, the potential for biomarker-based treatments, and the ability to track the efficacy of those treatments over time.

Materials and Methods

Fabrication of single cell capturing chip

Soft-lithography techniques were used to make the single cell capture device. In brief, an epoxy-based photoresist (SU-8 2025, MicroChem) was used to pattern a microfluidic channel on a silicon wafer. The wafer was then treated with trichlorosilane (Sigma Aldrich) under vacuum (1 hour). Polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS, Dow Corning) pre-polymer was mixed with a curing agent at a ratio of 10:1 (w/w), degassed under vacuum, and poured over the channel mold. The polymer was then cured on a hotplate (60°C, 1 hour). The cured PDMS structure was then peeled off, treated with O2 plasma, and irreversibly bonded to a glass slide. Before use, each device was flushed with pluoronic copolymer solution (0.02wt% F127 in water).

Flow rate optimization

We initially used 10 µm fluorescent microbeads (Bangs Laboratory) to test capture efficiency and to find the optimal flow rate. The bead solution was diluted to a concentration of 3000 beads/mL, and estimated 300 beads were introduced to the device. For the cell experiment, we used Daudi cells and prepared cell suspension with a concentration of ~104 cells/mL. An estimated 1000 cells were introduced into the device. Using a syringe pump, we applied negative pressure at the channel outlet to generate fluidic flow. The number of captured beads and cells were counted via fluorescence microscopy.

Cell lines

Cell lines were acquired from the following sources: DB, Toledo (Dr. Anthony Letai, Dana Farber Cancer Institute); RC-K8 (Dr. Thomas Gilmore, Boston University); SuDHL4, DOHH-2, Rec-1 (Dr. Russell Ryan, Massachusetts General Hospital); Daudi, Hut-78, Jurkat (ATCC). All cell lines (except Hut-78) were cultured (37°C and 5% CO2) in RPMI 1640 media (Invitrogen) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS). Hut-78 cell line was cultured (37°C and 5% CO2) in Iscove's Modified Dulbecco's Medium (Invitrogen) supplemented with 10% FBS.

Titration of cells

Approximately 1.5 × 106 cells from culture flasks were washed with PBS and stained for 30 min at room temperature in 1.5 µg/mL Hoechst 33342 (Invitrogen) and APC anti-human-CD45 antibody according to manufacturer instructions (Clone HI30, BioLegend) in PBS containing 2% bovine serum albumin (BSA; Sigma Aldrich). Following a quick wash with PBS, cells were fixed in 2.6% paraformaldehyde (PFA) in PBS at room temperature for 20 min. Cells were then triple washed with PBS, and passed through a nylon mesh (35 µm) to remove debris (Falcon® 5 mL tube with cell strainer cap, Corning). The cell concentration was measured using a hemocytometer (Hausser Scientific). The samples were diluted into quadruplicate aliquots of 10, 100, and 1,000 cells in 1 mL PBS in siliconized microtubes (Clear-view Snap-Cap, Sigma-Aldich). Each sample was then introduced to a preconditioned device at a flow rate of 2 mL/hr. The captured cells were then counted via microscopy.

Flow cytometry

Cells were fixed with 2.6% PFA (15 min at 37°C), 2× washed with PBS, and then incubated (30 min) in PBS containing 2% BSA (staining buffer, SB). Approximately 5 × 105 cells were incubated with 4.4 µg purified antibody in 42.5 µL SB (CD10, CD19, CD20, CD45, IgG) or with 2.5 µg purified antibody in 50 µL SB (κ light chain, λ light chain) for 30 min at 4°C. Antibody clones and manufacturers are listed in Supplementary Material: Table S2. For intracellular Ki-67 detection, we used a commercial kit (Foxp3/transcription factor staining buffer set, eBioscience) to fix and permeabilize cells. In brief, cells were treated with fixation/permeabilization (fix/perm) buffer, followed by incubation (30 min) with permeabilization/wash (perm/wash) buffer containing 2% BSA (permSB). 5 × 105 cells were then incubated with 5 µg purified anti-Ki-67 antibody (clone B56, BD) or mouse IgG control in 50 µL permSB for 30 min at 4°C. Cells were then washed 1× with SB or permSB, and incubated in 20 µL 1:100 R-phycoerythrin (PE) goat anti-mouse-IgG (H+L) (1 mg/mL, Invitrogen) secondary antibody for 30 min at 4°C in SB or permSB. Unstained controls were incubated in just SB or permSB at each step. Staining was done in 96-well V-bottom plates (Corning). Following 1× wash with SB or permSB, cells were resuspended into 200 µL PBS containing 0.5% BSA. Stained and unstained control samples were measured on a BD LSRII Flow Cytometer, and analysis was done using FlowJo software (Tree Star). Mean PE values were found for each cell line and antibody combination, and normalized to (signal - background)/(IgG - background) for CD10, CD19, CD20, CD45, and Ki-67 or (signal - background)/(secondary - background) for κ light chain and λ light chain.

On-chip cell staining and imaging

About 1000 DB, Daudi, or a 1:1 mixture of cells were diluted into 1 mL of artificial cerebrospinal perfusion fluid (aCSF; Harvard Apparatus) which closely matched the fluidic properties (viscosity, salt concentrations) of CSF. Samples were introduced to the device at the flow rate of 2 mL/hr. Following the cell capture, fix/perm buffer was perfused over the cells for 10 min, followed by permSB for 5 min, and PBS containing 2% FBS and 1% BSA for 5 min, all at a flow rate of 1 mL/hr. A cocktail of antibodies containing 1 µL of anti-Ki-67, anti-CD19, and anti-CD20, and 2 µL of anti-κ light chain and anti-λ light chain was perfused over the cells at 1 mL/hr for 5 min. Lastly, to reduce background signal from antibodies binding to the channel surface, washing buffer (PBS with 2% FBS and 1% BSA) was perfused at 1 mL/hr for 5 min. Alternatively, cells were exposed to Ibrutinib-BFL, followed by staining with Hoechst 33342 and anti-CD20-APC (clone 2H7; BioLegend). Images were captured on a Nikon Eclipse TE2000S inverted microscope (Nikon) equipped with four filter sets (#31000v2, #41001, #41002b, #41024; Chroma Technology).

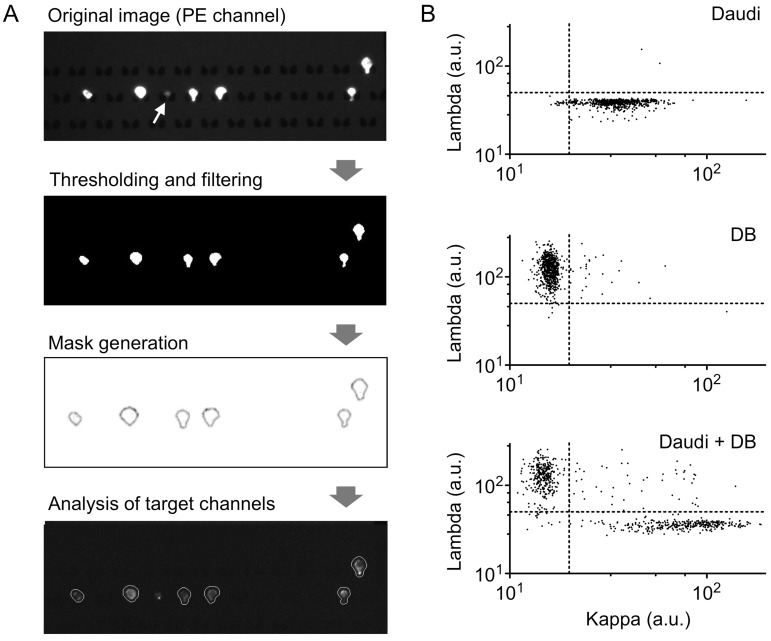

Image analysis

Images were analyzed using an in-house Matlab (Mathworks) script. Briefly, images from the CD19/20 (PE) channel were thresholded and binarized using Otsu's method. Following thresholding, image regions were analyzed and filtered by eliminating any regions greater or less then preset total pixel areas based on the magnification of the images. Additional noise was filtered using “open-close” morphological filtering. Boundaries of the remaining regions were then recorded and overlaid on target channels where values for the pixels in each mask area for both lambda (Alexa Fluor 647) and kappa (Brilliant Violet 421) channels were generated. Final values for both lambda and kappa channels for each cell were calculated by averaging the most intense 25% of pixels in each region.

Results

We designed a microfluidic chip to effectively handle heterogenous cell populations often found in CSF samples. First, size-selective capture sites were implemented to trap putative lymphoma cells (≥8 µm) in an unbiased, antibody-free fashion. Each capture site had a pass-through gap to remove small cells (e.g., erythrocytes). Second, the number of capture sites were large (24,000/chip) to ensure the identification of rare monoclonal populations; lymphoma cells make up as few as 0.1% of the total cells. To facilitate such analyses, the system was designed to allow for on-chip immunostaining and automated image processing.

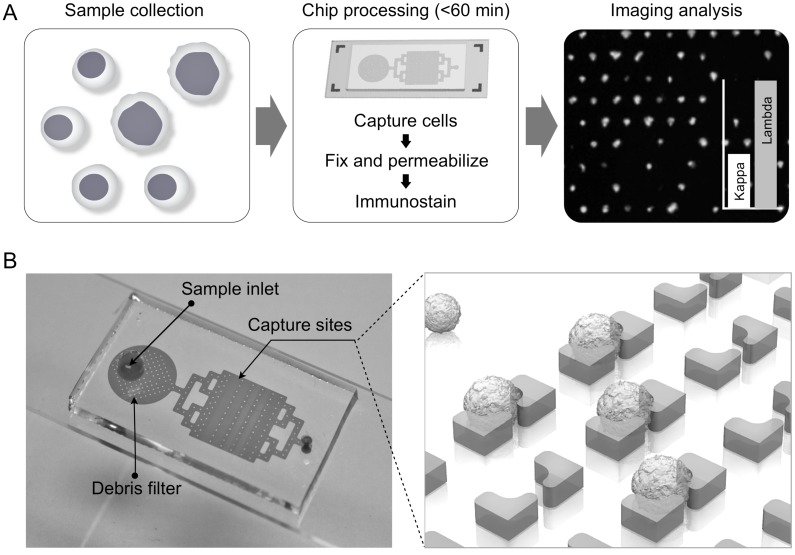

Fig. 1A summarizes the procedure for lymphocyte detection and profiling. First, samples are harvested, typically in the range of 1-3 mL. The entire sample is then loaded onto the chip; individual cells are captured in sub-nanoliter traps and on-chip stained for fluorescent imaging. Acquired images are then analyzed with an automatic computational algorithm to generate cell characterization data. The 2 × 4 cm2 chip contains 24,000 staggered, butterfly-shaped traps arranged in four bands of 20 × 300 (Fig. 1B; additional details in Supplementary Material). The capture site architecture was optimized to trap a single lymphocyte, while a 4-µm gap between the butterfly “wings” was incorporated to allow smaller cells, such as erythrocytes, to pass through without being captured (Supplementary Material: Fig. S1). Each trap was self-limiting; once a cell blocks the gap, the structure presents high fluidic resistance, preventing further cell-trapping. To remove cellular debris and aggregates, we also incorporated a column-filter in the sample inlet (Supplementary Material: Fig. S1). The chips were fabricated via standard soft lithography and the estimated cost per chip is <$1. Containing a large number of capturing sites, the chip enables high-throughput analysis. For instance, with typical flow rates of 2-5 mL/hr, target cells could be captured and stained in <1 hour, important for processing clinical samples.

Figure 1.

Process design. (A) Summary of overall scheme: paucicellular samples are harvested and captured on the chip without preprocessing. Following on-chip fixation, permeabilization, and immunostaining, the chip is imaged and cytometry is carried out with an in-house image process algorithm. (B) Photograph of lymphocyte capture chip attached to a microslide, showing inlet, debris filter, and capture area, which contains four arrays of 20 × 300 single-cell capture sites.

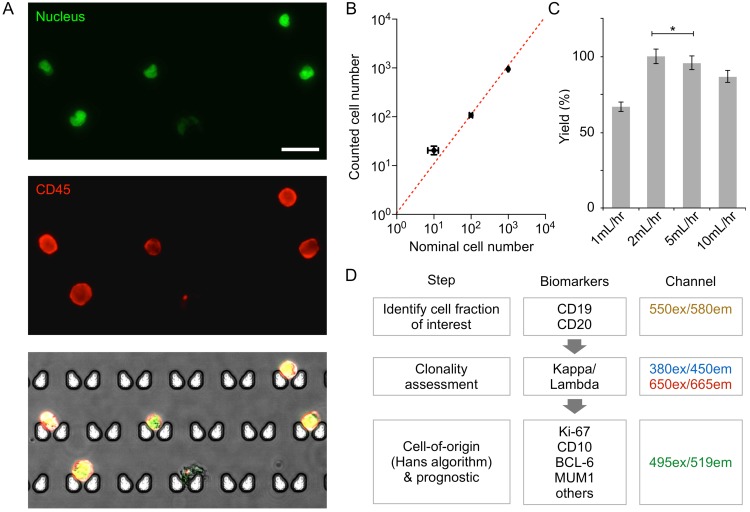

We first characterized the device performance for cell capture. DB GCB-type DLBCL and the Daudi Burkitt lymphoma cell lines were stained for CD45 (an extracellular pan-lymphocyte marker) and nucleus, and samples were prepared with the nominal cell counts of 10, 100, or 1000 of the DB or Daudi cells. When these samples were processed by the chip (Fig. 2A and 2B), the observed capture efficiency was >90%; this contrasts with the 17-30% cell loss that occurs at each centrifugation step in traditional sample processing 21,22. The optimal flow rate for maximal capture yield was between 2-5 mL/hr (Fig. 2C). At low flow rates (≤ 1 mL/hr), we observed that cells could switch to the flow stream that bypasses the capture site. When the flow speed increased, however, cells were quickly lodged into the capture site without diversion, which resulted in higher capture yield. We note that the capture yield was statistically identical at the flow rate of 2 and 5 mL/hr. For the subsequent cell experiment, we used the flow rate of 2 mL/hr to minimize potential cell lysis.

Figure 2.

Validation of on-chip capture and imaging. (A) DB cells dual-labeled with Hoechst and anti-CD45-APC, and captured and imaged on-chip. Capture sites are butterfly-shaped, staggered, and customized for lymphocyte size-based capture. Scale bar: 25 µm. (B) Capture efficiency of DB and Daudi cells is greater than 90% when 10, 100, or 1,000 lymphoma cells (nominal numbers) were introduced to the chip. The counted cell number is displayed as mean ± s.d. from quadruplicate measurements. The nominal cell number is displaced as mean ± Poisson error. (C) Optimization of flow rate based on capture efficiency of DB cells. (D) Proposed workflow for clinical diagnosis using image analysis.

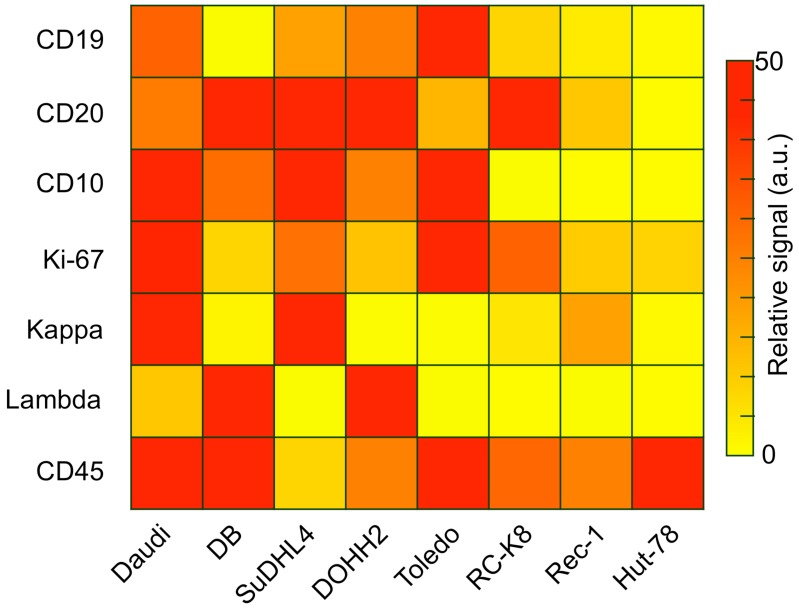

Captured cells could be analyzed on-chip through multi-color immuno-microscopy. As outlined in Fig. 2D, three classifications can be performed: 1) the use of CD19 and/or CD20 to determine B cells; 2) the use of kappa or lambda light chains to identify clonal populations; and 3) additional phenotypic markers for subtyping and prognostic tasks. We validated these markers and their respective antibodies by profiling a panel of cell lines via flow cytometry (Figure 3). Besides the B-cell lymphoma lines Daudi and DB, we also profiled SuDHL4, DOHH2, and Toledo GCB-type DLBCL lines, the RC-K8 ABC-type DLBCL line, and the Rec-1 mantle cell lymphoma line. Hut-78, a T-cell line, was used as a control. The profiling results showed the importance of including both CD19 and CD20 to identify B cells; not all B-cell lines were found to express both markers. This finding is also supported by other reports that showed decreased CD20 in lymphomas either due to the cancer cell-of-origin or anti-CD20 immunotherapy 23-25. We also found the restricted expression of kappa or lambda light chain surface immunoglobulins, which are markers of clonality, across the cell lines.

Figure 3.

Antibody validation and cell line profiling by flow cytometry. Relative expression levels of B-cell antigens relevant to diagnosis and prognosis (rows) on several lymphoma cell lines (columns). Daudi is a Burkitt's lymphoma line; DB, SuDHL4, DOHH2, and Toledo are GCB-type DLBCL lines, RC-K8 is an ABC-type DLBCL line, Rec-1 is a mantle cell lymphoma line, and Hut-78 is a T-cell lymphoma control.

Several different lymphomas arise from germinal center B cells, such as Burkitt and some DLBCLs (GCB-type), but most primary CNS lymphomas are ABC-type DLBCLs 26. As expected, we found that the GCB marker CD10 is expressed in all the GCB cell lines tested, but not in ABC-type or mantle cell lymphoma. Since ABC-DLBCLs tend to be more aggressive, we chose Ki-67 as an important marker for characterization and prognosis 27. Our data for the DB, DOHH2, and Rec-1 lines suggests that low Ki-67 in a monoclonal population would indicate the need to test additional lymphoma markers, such as for GCB-type DLBCL or mantle cell lymphoma. MUM1 may also be important, as it was shown to be expressed in over 90% of PCNSLs 26.

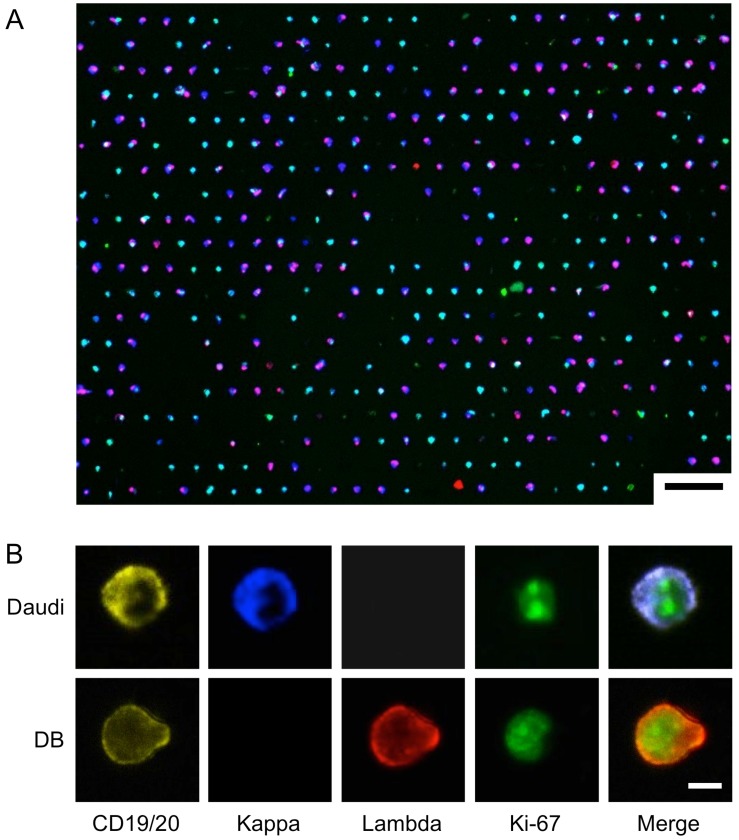

We chose to use Daudi and DB cells as a model system for on-chip analysis, since they respectively highly express kappa and lambda light chain. To demonstrate both extracellular and intracellular antigen analysis, we performed on-chip staining of CD19/CD20, kappa/lambda, and Ki-67. We prepared samples by spiking known numbers of DB and Daudi lymphoma cells into artificial CSF (see Methods for details). The cells were then fixed and stained on the chip, and imaged in four channels (Fig. 4; see Supplementary Material: Table S2 for antibody clones and fluorochromes). Fig. 4A shows the overlay of the four imaging channels after a 1:1 mixture of DB and Daudi cells were captured and stained on-chip. Fig. 4B demonstrates high-resolution imaging of individual cells and markers. Although the cell populations appear to be heterogeneous, their restricted kappa/lambda expression can be seen at higher magnification.

Figure 4.

On-Chip Imaging. A 1:1 mixture of DB and Daudi cells were captured and stained on-chip using a cocktail of antibodies: anti-CD19-PE, anti-CD20-PE, anti-Kappa-Brilliant Violet 421, anti-Lambda-Alexa Fluor 647, and anti-Ki-67-Alexa Fluor 488. (A) Low-magnification image shows overall capture site layout and cell heterogeneity. Scale bar: 75 µm. (B) High-resolution images of differential expression of individual markers on the two cell lines. Scale bar: 5 µm.

As a proof-of-concept of lymphocyte analysis from clinical samples, we developed an image-processing algorithm for clonality assessment. Following the workflow described in Fig. 2, we first made a mask around cells expressing CD19 and/or CD20, and then quantified the mean fluorescence intensity from our target channels in each individual cell (Fig. 5A). A size filter was also included to exclude non-cell debris from analysis (Fig. 5A, white arrow). We then analyzed images of a single cell-type population (either Daudi or DB; Fig. 5B). From ~600 individual cell images, we determined the threshold (Th) values of mean fluorescence intensities to distinguish each cell type (Daudi, Thkappa = 50; DB, Thlambda = 20). When these criteria were applied to another validation samples (>2,000 cells), we obtained high sensitivities (Daudi, 96%; DB, 99%) and specificities (Daudi, 98%; DB, 98%).

Figure 5.

Cell profiling for kappa/lambda monoclonality by image analysis. (A) Sample image analysis using an in-house image processing algorithm. Thresholding in the PE channel (CD19, CD20) is used to select B cells, and size-based filtering removes non-cell debris (white arrow). Target channels are analyzed within masks created from PE channel gating. (B) Scatterplots of mean pixel intensities from target imaging channels show clear separation of populations based on kappa and lambda light chain expression; top, DB cells; middle, Daudi cells; bottom, 1:1 mixture of DB and Daudi cells.

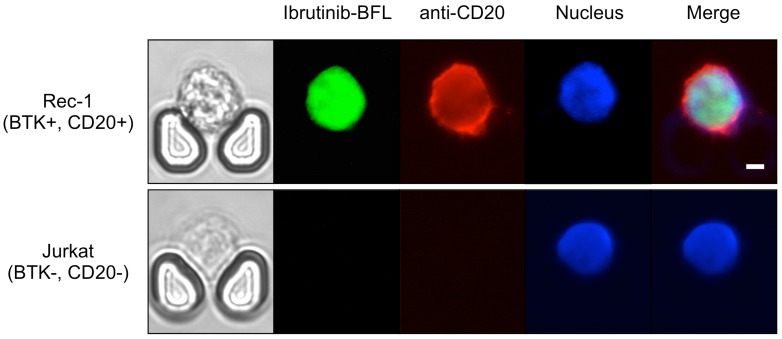

We further performed drug sensitivity testing that would be clinically useful to guide intrathecal and/or systemic chemo- and targeted therapies. We used a companion imaging drugs that has recently been reported, Ibrutinib-BFL, an inhibitor of Bruton's Tyrosine Kinase (BTK) 28; other imaging drugs include fluorescent rituximab or caged methotrexate. Ibrutinib is approved for several B-cell malignancies, including mantle cell lymphoma, and the Rec-1 cell line has been shown to be sensitive to the drug 29,30. Imaging the Rec-1 cells with Ibrutinib-BFL on the chip shows not only the binding of Ibrutinib, but also their cell-to-cell heterogeneity due to differences in BTK inhibitor sensitivity and BTK protein turnover (Fig. 6).

Figure 6.

Theranostic on-chip imaging. BTK-positive Rec-1 cells or BTK-negative Jurkat T-cell leukemia cells using fluorescent BTK inhibitor (Ibrutinib-BFL), anti-CD20-APC, and Hoechst stain. Note the high drug uptake and binding in Rec-1 cells. Scale bar: 5 µm.

Conclusion

CNS lymphoma is difficult to diagnose and characterize at the site of disease, often requiring multiple invasive lumbar punctures to retrieve sufficient numbers of cells to allow for cytopathologic analysis. To overcome the paucicellularity and heterogeneity of CSF samples, we developed a microfluidic filter platform that enables characterization of populations of lymphoma cells in the CSF on a single-cell level. Compared to membrane-based filters, the developed device offers two advantages: 1) individual cells are automatically arranged into a regular spatial array, which facilitates cell counting and image analysis, and 2) by maintaining a continuous fluidic flow through its operation, the device rarely clogs up. In the current study, we focused on testing the feasibility of the microfluidic-based lymphoma detection. We imaged both intracellular and extracellular diagnostic markers from lymphoma cells spiked into artificial CSF in under an hour, and further used an image-processing algorithm to quantitate their expression level.

For secondary CNS lymphoma, it is important to know the extent of disease, its aggression, and its response to treatment. Methotrexate is currently used intrathecally or at very high systemic doses to treat CNS disease, but it has thus far not been possible to track response to treatment other than by low resolution MRI or insensitive cytology, neither of which would catch minimal disease 31-33. By profiling lymphoid cells in CSF based on kappa/lambda restriction or proliferative grade, or by customizing antibody staining for intracellular or extracellular markers based on particular characteristics of the primary tumor (e.g. c-Myc rearrangement, CD10, CD5, etc.), CNS lymphoma cell counts can be tracked over time and prognostic assessments can be made 34,35. Additionally, there are several new lymphoma drugs in clinical trials, yet few are tested for CNS efficacy. This approach could provide a companion diagnostic that can directly test for brain-blood-barrier drug permeability or look for specific marker inhibition following intrathecal administration, such as BTK inhibitors or new generation anti-CD20 agents 36-39. To test for such drug accumulation (single cell pharmacokinetics) in primary lymphoma cells, we tested Ibrutinib-BFL directly on chip. Finally, another approach includes removing CSF after intrathecal injection of chemotherapy drugs to track treatment response over time.

Additional technologies can be added to front- or backend of the chip for further improvements and applications. For example, it will be possible to further purify B cells by negative selection of other cell types, such as T cells and monocytes. Since the capture is passive (i.e. no antibodies on the chip), we can also use tweezing methods to remove single cells of interest off the chip for further characterization, such as by quantitative PCR and sequencing — now possible on a single-cell level 40. Another possibility will be to add an imager or smartphone camera readout to enable the chip to be used for lymphoma diagnosis in resource-poor settings. We estimate that in this application a 1:5 cutoff ratio of kappa-to-lambda fluorescence signal would be enough to establish clonality with high specificity. The data presented here has led us to design a dedicated lymphoma diagnostic study using patient samples. Overall, we believe this new application of single-cell molecular profiling on a microfluidic chip for lymphoma will address questions regarding the diagnosis and treatment response of the disease not only in CSF, but also in other paucicellular samples such as fine needle aspirates, peritoneal fluid samples, pediatric applications or vitreous fluid analysis.

Supplementary Material

Figure S1, Tables S1-S2.

Acknowledgments

Authors 1, 2, and 3 contributed equally to this work. We thank A. Letai, T. Gilmore, and R. Ryan for cell lines, and the Harvard Center for Nanoscale Systems for use of their Nanofabrication cleanroom facility. A.T. was supported by the Harvard Biophysics Graduate Program under NIH training grant T32008313 and by an NSF Graduate Research Fellowship under grant numbers DGE0946799 and DGE1144152.

References

- 1.Schabet M. Epidemiology of primary CNS lymphoma. J Neurooncol. 1999;43:199–201. doi: 10.1023/a:1006290032052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Villano JL, Koshy M, Shaikh H, Dolecek TA, McCarthy BJ. Age, gender, and racial differences in incidence and survival in primary CNS lymphoma. Br J Cancer. 2011;105:1414–8. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2011.357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ziegler JL, Bluming AZ, Morrow RH, Fass L, Carbone PP. Central nervous system involvement in Burkitt's lymphoma. Blood. 1970;36:718–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Liang R, Chiu E, Loke SL. Secondary central nervous system involvement by non-Hodgkin's lymphoma: the risk factors. Hematol Oncol. 1990;8:141–5. doi: 10.1002/hon.2900080305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Quijano S, Lopez A, Manuel Sancho J. et al. Identification of leptomeningeal disease in aggressive B-cell non-Hodgkin's lymphoma: improved sensitivity of flow cytometry. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:1462–9. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.17.7089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gill S, Herbert KE, Prince HM. et al. Mantle cell lymphoma with central nervous system involvement: frequency and clinical features. Br J Haematol. 2009;147:83–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2009.07835.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.van Besien K, Ha CS, Murphy S. et al. Risk factors, treatment, and outcome of central nervous system recurrence in adults with intermediate-grade and immunoblastic lymphoma. Blood. 1998;91:1178–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Alizadeh AA, Eisen MB, Davis RE. et al. Distinct types of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma identified by gene expression profiling. Nature. 2000;403:503–11. doi: 10.1038/35000501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rubenstein JL, Fridlyand J, Shen A. et al. Gene expression and angiotropism in primary CNS lymphoma. Blood. 2006;107:3716–23. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-03-0897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dave SS, Fu K, Wright GW. et al. Molecular diagnosis of Burkitt's lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:2431–42. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa055759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lossos IS, Morgensztern D. Prognostic biomarkers in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:995–1007. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.02.4786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lenz G, Wright GW, Emre NC. et al. Molecular subtypes of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma arise by distinct genetic pathways. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:13520–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0804295105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bloomfield IG, Johnston IH, Bilston LE. Effects of proteins, blood cells and glucose on the viscosity of cerebrospinal fluid. Pediatr Neurosurg. 1998;28:246–51. doi: 10.1159/000028659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.de Graaf MT, Smitt PA, Luitwieler RL. et al. Central memory CD4+ T cells dominate the normal cerebrospinal fluid. Cytometry B Clin Cytom. 2011;80:43–50. doi: 10.1002/cyto.b.20542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Weston CL, Glantz MJ, Connor JR. Detection of cancer cells in the cerebrospinal fluid: current methods and future directions. Fluids Barriers CNS. 2011;8:14. doi: 10.1186/2045-8118-8-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hegde U, Filie A, Little RF. et al. High incidence of occult leptomeningeal disease detected by flow cytometry in newly diagnosed aggressive B-cell lymphomas at risk for central nervous system involvement: the role of flow cytometry versus cytology. Blood. 2005;105:496–502. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-05-1982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schroers R, Baraniskin A, Heute C. et al. Diagnosis of leptomeningeal disease in diffuse large B-cell lymphomas of the central nervous system by flow cytometry and cytopathology. Eur J Haematol. 2010;85:520–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0609.2010.01516.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Di Carlo D, Aghdam N, Lee LP. Single-cell enzyme concentrations, kinetics, and inhibition analysis using high-density hydrodynamic cell isolation arrays. Anal Chem. 2006;78:4925–30. doi: 10.1021/ac060541s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Di Carlo D, Wu LY, Lee LP. Dynamic single cell culture array. Lab Chip. 2006;6:1445–9. doi: 10.1039/b605937f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Peterson VM, Castro CM, Chung J. et al. Ascites analysis by a microfluidic chip allows tumor-cell profiling. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:E4978–86. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1315370110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dux R, Kindler-Rohrborn A, Annas M, Faustmann P, Lennartz K, Zimmermann CW. A standardized protocol for flow cytometric analysis of cells isolated from cerebrospinal fluid. J Neurol Sci. 1994;121:74–8. doi: 10.1016/0022-510x(94)90159-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kleine TO, Albrecht J, Zofel P. Flow cytometry of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) lymphocytes: alterations of blood/CSF ratios of lymphocyte subsets in inflammation disorders of human central nervous system (CNS) Clin Chem Lab Med. 1999;37:231–41. doi: 10.1515/CCLM.1999.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Johnson NA, Boyle M, Bashashati A. et al. Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: reduced CD20 expression is associated with an inferior survival. Blood. 2009;113:3773–80. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-09-177469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hiraga J, Tomita A, Sugimoto T. et al. Down-regulation of CD20 expression in B-cell lymphoma cells after treatment with rituximab-containing combination chemotherapies: its prevalence and clinical significance. Blood. 2009;113:4885–93. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-08-175208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Miyoshi H, Arakawa F, Sato K. et al. Comparison of CD20 expression in B-cell lymphoma between newly diagnosed, untreated cases and those after rituximab treatment. Cancer Sci. 2012;103:1567–73. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2012.02307.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Camilleri-Broet S, Criniere E, Broet P. et al. A uniform activated B-cell-like immunophenotype might explain the poor prognosis of primary central nervous system lymphomas: analysis of 83 cases. Blood. 2006;107:190–6. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-03-1024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Broyde A, Boycov O, Strenov Y, Okon E, Shpilberg O, Bairey O. Role and prognostic significance of the Ki-67 index in non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. Am J Hematol. 2009;84:338–43. doi: 10.1002/ajh.21406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Turetsky A, Kim E, Kohler RH, Miller MA, Weissleder R. Single cell imaging of Bruton's tyrosine kinase using an irreversible inhibitor. Sci Rep. 2014;4:4782. doi: 10.1038/srep04782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rahal R, Frick M, Romero R. et al. Pharmacological and genomic profiling identifies NF-kappaB-targeted treatment strategies for mantle cell lymphoma. Nat Med. 2014;20:87–92. doi: 10.1038/nm.3435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ponader S, Burger JA. Bruton's Tyrosine Kinase: From X-Linked Agammaglobulinemia Toward Targeted Therapy for B-Cell Malignancies. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:1830–9. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.53.1046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Abrey LE, Batchelor TT, Ferreri AJ. et al. Report of an international workshop to standardize baseline evaluation and response criteria for primary CNS lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:5034–43. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.13.524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Korfel A, Weller M, Martus P. et al. Prognostic impact of meningeal dissemination in primary CNS lymphoma (PCNSL): experience from the G-PCNSL-SG1 trial. Ann Oncol. 2012;23:2374–80. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdr627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Korfel A, Schlegel U. Diagnosis and treatment of primary CNS lymphoma. Nat Rev Neurol. 2013;9:317–27. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2013.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lossos IS, Czerwinski DK, Alizadeh AA. et al. Prediction of survival in diffuse large-B-cell lymphoma based on the expression of six genes. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:1828–37. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa032520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gurel B, Iwata T, Koh CM. et al. Nuclear MYC protein overexpression is an early alteration in human prostate carcinogenesis. Mod Pathol. 2008;21:1156–67. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2008.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Antonini G, Cox MC, Montefusco E. et al. Intrathecal anti-CD20 antibody: an effective and safe treatment for leptomeningeal lymphoma. J Neurooncol. 2007;81:197–9. doi: 10.1007/s11060-006-9217-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Younes A, Berry DA. From drug discovery to biomarker-driven clinical trials in lymphoma. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2012;9:643–53. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2012.156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wilson WH, Bromberg JE, Stetler-Stevenson M. et al. Detection and outcome of occult leptomeningeal disease in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma and Burkitt lymphoma. Haematologica. 2014;99:1228–35. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2013.101741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fleuren ED, Versleijen-Jonkers YM, Heskamp S. et al. Theranostic applications of antibodies in oncology. Mol Oncol. 2014;8:799–812. doi: 10.1016/j.molonc.2014.03.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zong C, Lu S, Chapman AR, Xie XS. Genome-wide detection of single-nucleotide and copy-number variations of a single human cell. Science. 2012;338:1622–6. doi: 10.1126/science.1229164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1, Tables S1-S2.