Abstract

Various modalities of renal replacement therapy (RRT) are available for the management of acute kidney injury (AKI) and end-stage renal disease (ESRD). While developed countries mainly use hemodialysis as a form of RRT, peritoneal dialysis (PD) has been increasingly utilized in developing countries. Chronic PD offers various benefits including lower cost, home-based therapy, single access, less requirement of highly trained personnel and major infrastructure, higher number of patients under a single nephrologist with probably improved quality of life and freedom of activities. PD has been found to be lifesaving in the management of AKI in patients in developing countries where facilities for other forms of RRT are not readily available. The International Society of Peritoneal Dialysis has published guidelines regarding the use of PD in AKI, which has helped in ensuring uniformity. PD has also been successfully used in certain special situations of AKI due to snake bite, malaria, febrile illness, following cardiac surgery and in poisoning. Hemodialysis is the most common form of RRT used in ESRD worldwide, but some countries have begun to adopt a ‘PD first’ policy to reduce healthcare costs of RRT and ensure that it reaches the underserved population.

Keywords: acute kidney injury, earthquake, intensive care unit pediatrics, peritoneal dialysis

Illustrative case report

A 16-year-old girl, weighing 40 kg, with body mass index of 15 kg/m2 with idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy underwent orthotopic allograft heart transplant on 09 August 2014. She was inducted with basiliximab, and immunosuppressants included prednisolone, tacrolimus and mycophenolate mofetil. Her preoperative creatinine was 1 mg/dL, and on post-operative day 3, she developed right heart failure with pulmonary arterial hypertension and prolonged oliguria. Using double-cuffed swan-neck Tenckhoff peritoneal dialysis (PD) catheter, she was initiated on acute PD using Dianeal solution (Baxter healthcare) with a dwell volume of 700 mL and dwell time of 60 min. Her mean dwell volume throughout dialysis was PD in ∼7000 mL and PD out ∼9000 mL for 24 h. Intermittent manual PD was continued from post-operative days 4 to 13. Serum creatinine was 0.6 mg/dL on Day 21, urine output 1.7 L/day and blood pressure 110/70 mmHg. Current echocardiogram shows adequate left ventricle function with ejection fraction of 60%. She developed ventilator-associated pneumonia due to Klebsiella pneumonia, which responded to intravenous meropenem. PD was a rescue therapy for a cardiac transplant patient with cardiorenal syndrome requiring renal replacement therapy (RRT).

In developing countries, PD has been successfully used to treat both acute kidney injury (AKI) and end-stage renal disease (ESRD). Despite a number of advantages that will be reviewed here, PD still remains underutilized. PD utilization in the intensive care setting varies from no usage at all in some developed nations to ∼46% in developing ones [1] where the lack of hemodialysis facilities [2], ease of implementing dialysis and economic considerations make this modality attractive [3, 4]. However, every year several million patients die in developing countries because of the lack of access to RRT to treat AKI or ESRD. Wider availability and use of PD could help mitigate this problem. We now review the current situation and perspective of PD use in the developing world.

Peritoneal dialysis in AKI

AKI is defined as an abrupt decline in glomerular filtration rate (GFR) resulting in progressive elevation of plasma urea and creatinine and is an important cause of morbidity and mortality worldwide [5]. Due to vagaries of nature, overcrowding and poor socioeconomic factors, AKI is common in developing countries but there is no reliable registry data on the incidence, prevalence, causes and recovery from the disease [6, 7]. AKI is a major cause of morbidity and mortality in critically ill patients and aging population in developing countries. About 30% of patients admitted to intensive care unit (ICU) develop hemodynamic instability, cardiorenal syndrome and sepsis [8, 9].

Dialysis modalities used in AKI are hemodialysis (HD), continuous renal replacement therapy (CRRT) and acute PD either manually or with automated machine in advanced centers. PD is practised for AKI treatment mostly due to its cost effectiveness, minimal infrastructure requirement and in rural areas where access to power, clean water supply and facilities for water treatment are lacking as in many developing countries where renal replacement centers are mainly located in major cities and towns [10, 11]. The availability of safe dialysis fluid in collapsible bags and easy procurement of stylet and flexible catheters has made PD an accessible and effective method for AKI treatment. PD does not require machinery and highly skilled persons for carrying out the procedure. PD can be invaluable at times when a major catastrophe damages the infrastructure such as earthquakes and flash floods [12]. During disasters, crush injuries are the second most common cause of death after direct trauma, and PD can save lives [13, 14]. In the wake of the Haiti earthquake in January 2010, Bartal and colleagues have suggested an algorithm to follow which includes PD [15]. The recent consensus guidelines published by ISPD on PD for AKI are an important step in providing RRT uniformly [16]. PD helps in better preservation of local renal hemodynamics and may be more physiologic and less inflammatory than HD due to the absence of contact between blood and synthetic membrane. PD is still an underutilized modality in developed countries for reasons that are unclear and they resort to CRRT, though doubts have been cast on the superiority of CRRT in multivariate analysis [17]. CRRT requires multiple accesses to blood stream in critically ill patients, which predisposes them to blood borne infections in less ideal situations in developing countries. PD is hemodynamically friendly and requires only a single access to peritoneal cavity, and fluid removal can be smoothly achieved by altering the concentration of glucose in the dialysis fluid. Continuous glucose absorption provides nutritional benefits to the critically ill patient.

Techniques of acute PD

There are five types of acute PD namely acute intermittent peritoneal dialysis (AIPD), continuous flow peritoneal dialysis (CFPD), continuous equilibration peritoneal dialysis (CEPD), tidal peritoneal dialysis (TPD) and high volume peritoneal dialysis (HVPD). These different techniques are used according to patient requirement and facility preference. The urea clearance is 8–12 mL/min for AIPD, 15 mL/min for TPD and 30–35 mL/min for CFPD [18] (Table 1) [19].

Table 1.

Techniques of PD for AKI [19]

| Technique | Description |

|---|---|

| AIPD | Most often used in the past. Frequent and short exchanges with volumes 1–2 L and dialysate flows of 2–6 L/h. Each session lasts 16–20 h, usually tri-session per week. The solute clearance is likely inadequate due to its intermittent nature. |

| Continuous equilibration peritoneal dialysis (CEPD) | Long dwells of 2–6 h with up to 2 L of dialysate each (similar to CAPD). The clearance of small molecules may also be inadequate but clearance of middle molecules is possibly higher due to the long dwells. |

| TPD | Typically involves an initial infusion of 3 L of dialysate into the peritoneal cavity. A portion of dialysate, tidal drain volume (usually 1–1.5 L) is drained and replaced with fresh dialysate (tidal fill volume). The reserve volume always remains in the peritoneal cavity throughout the tidal cycle. |

| HVPD | Continuous therapy proposed to increase high small solute clearances. Frequent exchanges, usually with cycler (18–48 exchanges per 24 h, 2 L per exchange). The total dialysate volume range from 36 to 70 L a day. |

| CFPD | In-flow and out-flow of dialysate occurs simultaneously through two access routes. By inflow of 300 mL/min, it is possible to achieve a high peritoneal urea clearance. |

Types of PD catheter

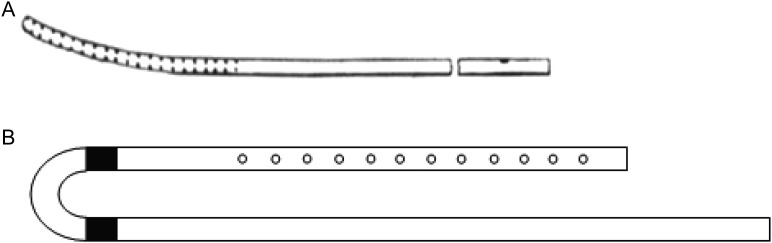

There are two types of PD catheter (Figure 1).

Rigid catheter: it is cheap and easier to insert; however, there is a slightly increased risk of peritonitis, catheter dysfunction and poor dialysate flow when compared with a flexible catheter.

Flexible catheter: it accommodates a higher dialysate flow rate but it has a higher cost; however, locally manufactured in India by the first author has brought down the cost substantially. Swan neck configuration prevents catheter migration from the pelvis. This can be inserted at bedside using a trocar or a peel-away sheath technique.

Fig. 1.

(A) Rigid catheter in PD. (B) Flexible swan neck catheter used in PD.

The approximate cost of PD per day in developing countries includes cost of fluid (US$24 to 27), catheter (Stylet-US$6.6 and flexible Tenckhoff—US$30) and cost effective implantation charges. In comparison, cost of CRRT access, fluids, equipment and trained personnel is higher (US$400 to 800) per day. Total cost of intermittent HD including consultation per day comes to around US$104, with access US$66 and daily dialysis cost US$38. Professional reimbursement varies depending on whether it is done under a free scheme or a profit-oriented corporate hospital sector.

ISPD guidelines for PD in AKI

ISPD guidelines state that PD should be considered as a suitable method for RRT in AKI [8]. Flexible peritoneal catheters should be preferred over rigid catheters when available. Catheter insertion by a nephrologist is safe and functional results equal that of surgical insertion. The Cochrane systematic review of 2004 indicates that use of preoperative prophylactic antibiotics such as first generation cephalosporins or vancomycin reduces the incidence of peritonitis among PD patients [20].

In multi-organ failure and shock, it is appropriate to insert PD catheter at bedside. ISPD recommends use of PD fluids with bicarbonate as the buffer in patients with shock or liver failure as they are at high risk of accumulation of lactate and worsening metabolic acidosis.

Fluid overload is to be avoided, and ultrafiltration can be increased by raising the concentration of dextrose and shortening the cycle duration. Targeting a weekly kT/V of 2.1 may be acceptable. CFPD can be considered when an increase in solute clearance and ultrafiltration is desired.

PD in neonatal and pediatric AKI

AKI is seen in 3–5% of patients in pediatric and neonatal ICUs and is associated with higher mortality [21]. PD should be the treatment of choice in neonatal and pediatric AKI. The common indications for PD are AKI due to acute diarrheal illness, septicemia and hemolytic uremic syndrome. The peritoneal surface area per unit weight is twice that in infants as in adults which is beneficial. PD use should be adjusted according to the patient's needs [21]. It is recommended to use frequent, continuous low volume (10–20 mL/kg body weight, 300–600 mL/m2) exchanges with adequate ultrafiltration rate [21]. This recommended approach has been beneficial in preventing dialysate leakage and lung compression. Short dwell times of ∼20 min have been effective in infants, but there is a risk of sodium sieving. ICU nurses can be taught by a PD nurse specialist to perform manual exchanges quickly. However, patients in ICU frequently experience multi-organ failure, hypercatabolism and shifts in volume status, and hence, dialysis adequacy must be cautiously monitored and defined [21]. As in patients with cirrhosis, neonates and infants should also preferably be dialyzed with PD fluids with bicarbonate buffer only as the metabolism of lactate is impaired in this population.

PD in AKI in adults

PD has been found to be an adequate form of treatment for AKI occurring as a result of snake bites especially the Russell's viper, malaria, leptospirosis, gastroenteritis, febrile illness, sepsis, acute pancreatitis, rhabdomyolysis, hepatorenal syndrome, following cardiac surgery and poisoning such as barbiturates, lithium, ethylene glycol and boric acid [22–25], more so when hemodialysis facilities are not immediately available though the two modalities have never been compared.

Dr. Sergio et al. compared the use of PD for AKI in ICU and ward settings in Europe, Asia and North America by administering an anonymous self-administered questionnaire distributed to attendees at three dialysis meetings in 2009 [26]. Though half of the respondents felt that PD was a suitable modality for most AKI patients admitted in the ward, there was a marked discrepancy in opinion and reality as only 22% were actually using the modality. Both in the ICU setting and in the wards, PD was used in ∼46% in Asia-Pacific/Australasia regions and to a far lesser extent in Europe and North America, 18.9 and 12.2%, respectively. In addition, most of the physicians irrespective of their respective continent were unsure about the adequate PD dosing for AKI.

In our tertiary care center, we prefer PD over HD in acute settings such as heart failure, hemodynamic instability, bleeding diathesis and cholesterol atheroembolic disease. Extra-corporeal therapies in patients with significant cardiac disease can lead to electrolyte disturbances, hypotension and poor myocardial function, which are less likely while using PD. Those patients may also require thrombolysis and other interventions which are hurdles while contemplating extra-corporeal therapies. We retrospectively analyzed the outcome of AKI using PD as a cost-effective modality for AKI patients with myocardial infarction, cardiogenic shock and cardiac dysrythmias. PD was provided for 84 patients with cardiorenal syndrome type 1 among 6687 patients admitted to the coronary care unit (CCU) over a period of 36 months. Males were 64% and mean age 59 ± 11 years. The mortality rate was 14%. Of the remaining 72 patients, we observed functional recovery in 68 patients (81%) and 4 (5%) patients were transferred to temporary HD because of exit site leak. Complications were exit-site leak in eight patients (9.5%) that was less frequent with a swan neck double-cuff Tenckhoff catheter (1 of 43, 0.023% versus 7 of 41, 0.17%; P = 0.021). None developed peritonitis. We observed a decrease in serum creatinine by 47% (P < 0.0001).

Advanced age, poor cardiac function, hypercatabolic stage, hemodynamic instability and diabetes mellitus are associated with poor outcome in AKI patients. Appropriate volume control by monitoring ultrafiltration with minimal hemodynamic disturbance and using aseptic techniques with use of dialysis fluid in collapsible bags can favorably influence the outcome of AKI in the CCU setting. Management of reversible AKI by early detection and use of PD is feasible, effective and affordable [27].

The major question raised regarding PD in AKI was in 2002 by an open–labeled, randomized study from Vietnam, which showed a higher mortality rate in AKI patients treated with PD than that in patients treated with continuous venovenous hemofiltration (CVVH) (47 versus 15%, P = 0.005) [3]. Another prospective, randomized crossover study showed acceptable outcome of both TPD and CEPD in treating hyper catabolic AKI in developing countries although concerns were expressed about the use of PD in hypercatabolic AKI patients [28] since only TPD achieved adequacy as per guidelines but there was excess protein removal. Gabriel et al. [29] in a prospective, randomized, controlled trial showed there is no significant difference in the rate of infectious complications observed between HVPD group and intermittent daily HD group. HVPD group patients received two-liter exchanges (36–44 L per day over 18–22 exchanges) adjusted to prescribe a Kt/V of 0.65 per day. Both HVPD and intermittent daily HD lead to low serum albumin and declined equally in both modalities. The mortality rate was not significantly different (58% for HVPD versus 53% for intermittent HD), nor was the rate of renal recovery [20]. George et al. in an open-labeled, randomized trial compared PD with continuous venovenous hemodiafiltration (CVVHDF) by emphasizing uremia correction, electrolyte and acid base disorders and correction of fluid overload [30]. Urea and creatinine clearance was higher with CVVHDF than PD. PD showed better control of acid-base balance as compared with CVVHDF. Fluid correction was faster with CVVHDF. Both modalities showed a similar result with respect to correction of hyperkalemia and hemodynamic instability. PD was extremely cost-effective as compared with CVVHDF with no difference in mortality (84% in CVVHDF group versus 72% in PD group (P = 0.49).

Limitations of PD in AKI

Though cheap, easy and reliable, PD has limitations in the treatment of AKI [31], the most important being its need for an intact peritoneal cavity with adequate peritoneal clearance capacity and its less efficacy for severe acute pulmonary edema and in life threatening hyperkalemia. Unlike HD, ultrafiltration and clearance cannot be exactly predicted in PD and its adequacy is of some concern in hypercatabolic patients. In CCU settings where patients are on ventilation, PD using high volume may impair diaphragmatic movement and this should be taken into consideration while profiling the patient. The buffer used is rarely bicarbonate, and there is concern about protein loss and hyperglycemia. The effective peritoneal blood flow in uremic patients during dialysis is 100 mL/min [32] and cannot be increased as in the case of CRRT and HD. However, it must be emphasized that in nearly all the above-mentioned situations, PD may be tried as the initial RRT modality and prescription adjusted to get optimum dialysis and ultrafiltration.

Contraindications to PD in AKI

The contraindications of PD in AKI are similar to those in CKD, namely, a large pleuroperitoneal communication, recent abdominal surgery and a history of multiple previous abdominal surgeries leading to peritoneal adhesions

Peritoneal dialysis for chronic kidney disease

In 1894, Starling from Guy's Hospital, London, first documented the principles of PD when he observed that concentrated saline in the peritoneum withdrew fluid from capillaries, dilute saline did the opposite and isotonic saline did neither [33]. It is a lesser known fact that PD was the earliest modality of RRT to be attempted for chronic kidney disease (CKD) when 33-year-old Ms. Mae Stewart was kept on PD for 7 months [34]. PD has come a long way since then being used for about four decades with >250 000 ESRD patients worldwide [35]. Due to increasing life expectancy, risk factors and screening, there has been an increasing prevalence of CKD and ESRD [36].

PD as ‘first choice’ for ESRD patients

Unfortunately, PD and HD are often contrasted rather than their complementary roles understood. Use of PD as ‘initial’ RRT modality is probably advantageous for more patients than are utilizing this modality presently, probably because of better survival in initial 2 years. Flexibility of schedule, freedom from mandatory hospital visits thus saving time and convenience of doing dialysis at one's own home are compelling reasons to start PD [37]. Patients on PD are free to pursue careers, travel around and engage in social activities without illness intrusion. With improvements in technique, PD-related infections are declining whereas they are increasing in HD patients. The risk of septicemia, hospitalization and death thereby are higher in HD patients [38]. Transplant recipients previously on PD are likely to have faster decline in plasma creatinine, less likely to develop delayed graft function [39] and are at lower risk of death and graft failure [40], making PD the preferred modality in prospective recipients. In most patients, PD permits initial preservation of residual renal function (RRF) with the native kidneys' contribution to improved middle molecular clearance, fluid status, cardiac function, nutrition, hemoglobin levels, bone-mineral metabolism and quality of life [41].

Survival of ESRD in patients on PD

Survival on PD was believed to be superior in initial 2 years and HD scoring thereafter [42], but the data had residual confounding [43] and survival is similar when elective, outpatient, incident dialysis patients are compared. When data of Canadian Organ Replacement Register and United States Renal Data System [44] were properly analyzed, survival was similar. After stratifying for age, gender and diabetic status, survival on PD was better in younger non-diabetic patients, survival of older diabetics was better on HD and similar in all the rest. Similar data from developing countries are lacking and may be different. The Chinese randomized control trial (NCT 01413074) comparing survival between the two modalities is complete, and the results may finally end the debate [45].

PD for ESRD across the globe: the impact of socioeconomic and policy factors

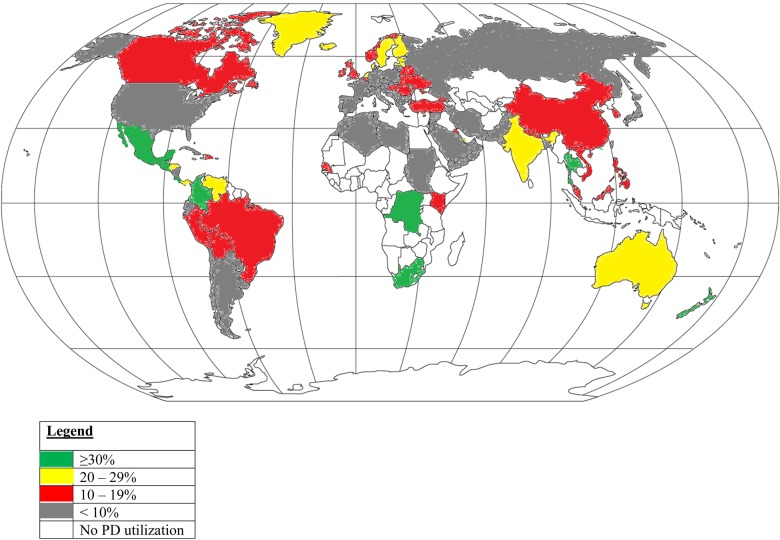

Of all ESRD patients on PD, 41% are in developed countries. Of the entire chronic dialysis population, only 11% are on PD with Mexico, USA and China having the largest absolute number of patients. Apart from Mexico, Hong Kong, El Salvador and Guatemala, HD is the predominant RRT modality worldwide [46]. The proportion of PD patients among prevalent dialysis patients varies widely from <1% to ∼80% (Figure 2), the latter in countries with ‘PD first’ policy. PD has been growing exponentially in Thailand because of recently introduced ‘PD first’ policy [46]. Although the nephrology community generally agrees that PD utilization should be ∼25–30% [47], current rates are far lower. Within certain countries such as France, Spain and Italy, utilization rates vary tremendously, suggesting that some are ‘believers’ and many are ‘nonbelievers’ in PD [46].

Fig. 2.

Utilization of PD for chronic dialysis (prevalence) across the globe.

In Australia, Canada, Netherlands, New Zealand, most of Scandinavia and United Kingdom, where dialysis is provided by the government, utilization of PD is higher (20–30%) and is propagated as the cheaper modality [48]. HD predominates in Japan, USA, Germany, Belgium and most south European countries where dialysis is provided by private sector, reimbursement being a strong incentive for HD utilization [49] relegating PD utilization to <10%. Japan's fee-for-service remuneration policy caused 96% of ESRD patients to receive in-center HD [50].

In Hong Kong, cost effectiveness of CAPD led to the establishment of ‘PD first’ policy by the Central Renal Committee in 1985 and PD has grown [51] to ∼80% prevalence [35, 46]. Renal physicians and specialist nurses introduce CKD concepts and various RRT modalities with emphasis on independent RRT via CAPD with its inherent procedural simplicity, flexibility, continuous nature and importance of RRF preservation. Interactive patient groups are formed in each dialysis center with patient rehabilitation using sports, games and other competitions. These help patients to adapt to their illness easily and live relatively normal lives [52, 53].

In developing countries, more than half the patients present with CKD stage 5 as the initial presentation of renal illness [54]. It becomes imperative that RRT is planned at the time of diagnosis. PD should become the default modality for the largely non-urban population. A case in point is the very high PD utilization in Mexico [55], because of the presence of few certified nephrologists, governmental ‘PD first’ policy combined with public institutions being major dialysis providers, absence of a reimbursement system (all doctors are salaried), increased experience with PD during nephrology training and local production of PD fluid, the latter forcing multinational competitors to lower prices. HD centers in Mexico are only situated in large cities and thus are inaccessible for most [56]. Home PD thus is an excellent RRT modality for ESRD patients in the developing world who live in remote villages with poor access to HD facilities [56, 57]. The Thailand government reduced the fluid import duty while implementing a ‘PD first’ policy. This made PD cheaper [58] while increasing utilization [59].

Cost of doing PD is less than HD in most countries, especially in the developed world [60]. The governmental ‘PD first’ policy of Hong Kong has resulted in PD costs being less than half of HD [52] whereas greater remuneration for HD results in enlisting more patients on HD in facilities, thus reducing actual per-patient cost of providing care [61]. Similar remuneration for both HD and PD as implemented in the USA recently [62] should allow more utilization of PD. In south Asian countries like India, most PD patients do not have health insurance and have to pay for their monthly fluid supplies. The one-time payment for life-long fluid supplies has been available for the past decade improving PD utilization [63]. Poor accessibility of remote villages to PD fluid suppliers, especially across mountainous terrains remains a challenge in some areas. Problems of space constraints for doing PD exchanges, availability of running water for hand-washing and poor hygienic living conditions still pose a challenge in many but are slowly being successfully addressed.

Chronic PD in children

Children with ESRD are best managed with transplantation with better quality of life and superior long-term survival. When transplantation is delayed, PD is the preferred RRT modality in children allowing them flexibility of therapy in concordance with their educational and other lifestyle requirements [64]. PD is the ideal modality of RRT in children, and especially so when the weight is <5 kg for those who, have a difficult vascular access and where anticoagulation is contraindicated. Since the number of children on PD is relatively small globally, pooled clinical data from the North American Pediatric Renal Trials and Collaborative Studies, International Pediatric Peritonitis Registry and pediatric ESRD registries of European Society for Pediatric Nephrology/European Renal Association-European Dialysis and Transplant Association (ESPN/ERA-EDTA) and the International Pediatric Peritoneal Dialysis Network are collated to obtain more generalizable information. The 5-year technique survival appears to have been improving from 64% in the pre-1992 era to 78% thereafter in the Japanese registry [65] with peritonitis and ultrafiltration, together contributing to two-thirds of the reasons for technique failure. Patient survival is better in those older than 5 years of age [66]. Similar data are lacking from developing countries.

The problems of hypertension in more than two-thirds of the children (contributing to left ventricular hypertrophy in 50%) [67], severe hyperphosphatemia and hyperparathyroidism in half [68], growth impairment and malnutrition especially in infants [69] are somewhat unresolved with no clear recommendations for treatment. Unique to the developing world is poor availability of small dialysate bags restricting utilization of PD. Unavailability of specialized HD units makes children to be dialyzed in adult HD units making PD an attractive option.

PD for chronic dialysis ‘crash starts’

Worldwide, most patients who start on dialysis without pre-dialysis education (‘crash starts’) are started on HD via a temporary central venous catheter in the internal jugular vein. These are associated with high mortality in the first 3 months [70]. The available literature on similar unplanned PD initiation suggests similar mortality between PD and HD [71]. Between planned and ‘crash start’ patients on PD, the latter group is likely to have a higher mortality and risk of hospitalization related to more comorbidities, poorer biochemistry profile [72] and older age [73].

Infections (including bacteremia) occur more in patients who ‘crash start’ HD than PD. The latter group's peritonitis rates are similar to those on planned PD but have a greater risk of mechanical complications [73]. Except in patients with severely uncontrolled hypertension, pulmonary edema, severe hyperkalemia or uremic pericarditis/colitis, most may be suitable candidates for a PD ‘crash start’ and this should be offered to all eligible patients.

Bedside percutaneous PD catheter insertion by nephrologists obviating the requirement of a long break-in period, acute start of chronic PD can be done successfully with the added advantages of short hospital stay, non-requirement of operation room facilities and personnel (including surgeons and anesthetists) and reduced costs [74]. This can be successfully employed even in patients with past abdominal surgeries with low likelihood of peritoneal adhesions [75].

Glucose-based fluids and ‘biocompatible fluids’

The high glucose concentration of conventional PD fluid creates an osmotic gradient for ultrafiltration. The low PD fluid pH reduces formation of glucose degradation products (GDPs). The substantial carbohydrate load from PD fluid can lead to high blood sugars and a potentially atherogenic lipoprotein profile. Locally, PD fluid glucose, low pH, lactate and GDPs [76] cause long-term unfavorable effects on the membrane. Systemic absorption of GDPs may decrease RRF by their action on renal tubules [77]. The ‘biocompatible’ PD solutions are associated with lower peritonitis rates in most series. In the randomized, controlled trial, balANZ study, peritonitis rate was 0.49 in the conventional group and 0.30 episodes per patient-year in the biocompatible fluid group (P = 0.01) [78]. There may be increased RRF as evidenced by increased GFR and urine output possibly due to renoprotective effect of reduced GPDs in these fluids [79]. However, newer solutions may change the patient's transport status and decrease ultrafiltration by 30%, volume expansion thus caused possibly increasing urinary volume [78]. Although two trials showed a mortality advantage, the balANZ study did not [78]. Of the newer solutions, only icodextrin is freely available in most developing countries and is ∼45% costlier.

Conclusion

Looking globally, the majority of the population lives in developing countries and two-thirds are living at or below the poverty line. AKI is common in such populations due to a variety of causes. Dialysis modality should be simple, cost-effective to save lives. Hence, PD is the treatment of choice. Chronic PD including CAPD, which is a home-based therapeutic modality, is expanding in developing countries. Manufacturing catheter and dialysis fluid in developing countries will bring down the cost of PD, thereby making a PD first policy in different parts of the world.

Conflict of interest statement

None declared. The results presented in this paper have not been published previously in whole or part, except in abstract format.

References

- 1.Beginning and Ending Supportive Therapy for the Kidney (BEST Kidney) Investigators. Acute renal failure in critically ill patients: a multinational, multicenter study. JAMA 2005; 294: 813–818 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sharma SK, Manandhar D, Singh J, et al. Acute peritoneal dialysis in Eastern Nepal. Perit Dial Int 2003; 23 (Suppl 2): S196–S199 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Phu NH, Hien TT, Mai NT, et al. Hemofiltration and peritoneal dialysis in infection-associated acute renal failure in Vietnam. N Engl J Med 2002; 347: 895–902 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mohandas N, Chellapandian D. Value of intermittent peritoneal dialysis in rural setup. Indian J Perit Dial 2004; 6: 19–20 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bellomo R, Kellum JA, Ronco C. Acute kidney injury. Lancet 2012; 380: 756–766 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kilonzo KG, Ghosh S, Temu SA. Outcome of acute peritoneal dialysis in Northern Tanzania. Perit Dial Int 2012; 32: 261–266 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chugh KS, Sakhuja V, Malhotra HS, et al. Changing trends in acute renal failure in third-world countries—Chandigarh study. Q J Med 1989; 73: 1117–1123 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hoste EA, Clermont G, Kersten A, et al. RIFLE criteria for acute kidney injury are associated with hospital mortality in critically ill patients: a cohort analysis. Crit Care 2006; 10: R73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shah BN, Greaves K. The cardiorenal syndrome: a review. Int J Nephrol 2010; 2011: 920195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gabriel DP, Nascimento GV, Caramori JT, et al. Peritoneal dialysis in acute renal failure. Ren Fail 2006; 28: 451–456 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ronco C. Can peritoneal dialysis be considered an option for the treatment of acute kidney injury? Perit Dial Int 2007; 27: 251–253 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kumar V, Ramachandran R, Rathi M, et al. Peritoneal dialysis: the great savior during disasters. Perit Dial Int 2013; 33: 327–329 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sever MS, Erek E, Vanholder R, et al. Renal replacement therapies in the aftermath of the catastrophic Marmara earthquake. Kidney Int 2002; 62: 2264–2271 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vanholder R, Sever MS, De Smet M, et al. Intervention of the renal disaster relief task force in the 1999 Marmara, Turkey earthquake. Kidney Int 2001; 59: 783–791 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bartal C, Zeller L, Miskin I, et al. Crush syndrome: saving more lives in disasters: lessons learned from the early-response phase in Haiti. Arch Intern Med 2011; 171: 694–696 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cullis B, Abdelraheem M, Abraham G, et al. Peritoneal dialysis for acute kidney injury. ISPD guidelines/recommendations. Perit Dial Int 2014; 34: 494–517 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Watcharotone N, Sayumpoorujinant W, Udompon U, et al. Intermittent peritoneal dialysis in acute kidney injury. J Med Assoc Thai 2011; 94: S126–30 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Burdmann EA, Chakravarthi R. Peritoneal dialysis in acute kidney injury: lessons learned and applied. Semin Dial 2011; 24: 149–156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nada D. Peritoneal dialysis in acute kidney injury. BANTAO J 2010; 8: 54–58 [Google Scholar]

- 20.Strippoli GFM, Tong A, Johnson DW, et al. Antimicrobial agents for preventing peritonitis in peritoneal dialysis patients. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2004; 4: CD004679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bonilla Felix M. Peritoneal dialysis in the pediatric intensive care unit setting. Perit Dial Int 2009; 29 (Suppl 2): S183–S185 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mishra SJ, Mahanta KC. Peritoneal dialysis in patients with malaria and acute kidney injury. Perit Dial Int 2012; 32: 656–659 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wiwanitkit V. Management of acute renal failure due to Russell's viper envenomation: an analysis of reported Thai cases. Renal Failure 2005; 27: 801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Charen E, Dadzie K, Sheth N, et al. Hepatorenal syndrome treated for 8 months with continuous flow peritoneal dialysis. Adv Perit Dial 2013; 29: 38–42 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Teitelbaum I. Peritoneal dialysis after cardiothoracic surgery: do it! Perit Dial Int 2012; 32: 131–133 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gaião S, Finkelstein FO, de Cal M, et al. Acute kidney injury: are we biased against peritoneal dialysis? Perit Dial Int 2012; 32: 351–355 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lameire NH, Bagga A, Cruz D, et al. Acute kidney injury: an increasing global concern. Lancet 2013; 382: 170–179 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chitalia VC, Almeida AF, Rai H, et al. Is peritoneal dialysis adequate for hypercatabolic acute renal failure in developing countries? Kidney Int 2002; 61: 747–757 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gabriel DP, Caramori JT, Martim LC, et al. High volume peritoneal dialysis vs daily hemodialysis: a randomized, controlled trial in patients with acute kidney injury. Kidney Int Suppl 2008; S87–S93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.George J, Varma S, Kumar S, et al. Comparing continuous venovenous hemodiafiltration and peritoneal dialysis in critically ill patients with acute kidney injury: a pilot study. Perit Dial Int 2011; 31: 422–429 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yong K, Dongra G, Boudville N, et al. Acute kidney injury: Controversies revisited. Int J Nephrol 2011; 762634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Grzegorzewska AE, Antoniewicz K. Effective peritoneal capillary blood flow and peritoneal transfer parameters. Adv Perit Dial 1993; 9: 8–11 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Starling EH, Tubby AH. On absorption from and secretion into the serous cavities. J Physiol 1894; 16: 140–148 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.McBride P. Paul Doolan and Richard Rubin: performed the first successful chronic peritoneal dialysis. Perit Dial Int 1985; 5: 84–86 [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jain AK, Blake P, Cordy P, et al. Global trends in rates of peritoneal dialysis. J Am Soc Nephrol 2012; 23: 533–544 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Li PK, Weening JJ, Dirks J, et al. Participants of ISN Consensus Workshop on Prevention of Progression of Renal Disease. A report with consensus statements of the International Society of Nephrology 2004 Consensus Workshop on Prevention of Progression of Renal Disease, Hong Kong, June 29, 2004. Kidney Int 2005; (Suppl 94): S2–S7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chaudhary K, Sangha H, Khanna R. Peritoneal dialysis first: rationale. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2011; 6: 447–456 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Powe NR, Jaar B, Furth SL, et al. Septicemia in dialysis patients: incidence, risk factors and prognosis. Kidney Int 1999; 55: 1081–1090 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Vanholder R, Heering P, Loo AV, et al. Reduced incidence of acute renal graft failure in patients treated with peritoneal dialysis compared with hemodialysis. Am J Kidney Dis 1999; 33: 934–940 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Goldfarb-Rumyantzev AS, Hurdle JF, Scandling JD, et al. The role of pretransplantation renal replacement therapy modality in kidney allograft and recipient survival. Am J Kidney Dis 2005; 46: 537–549 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wang AY, Lai KN. The importance of residual renal function in dialysis patients. Kidney Int 2006; 69: 1726–1732 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Termorshuizen F, Korevaar JC, Dekker FW, et al. Netherlands Cooperative Study on the Adequacy of Dialysis Study Group. Hemodialysis and peritoneal dialysis: comparison of adjusted mortality rates according to the duration of dialysis: analysis of The Netherlands Cooperative Study on the Adequacy of Dialysis 2. J Am Soc Nephrol 2003; 14: 2851–2860 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Noordzij M, Jager KJ. Survival comparisons between haemodialysis and peritoneal dialysis. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2012; 27: 3385–3387 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mehrotra R, Chiu YW, Kalantar-Zadeh K, et al. Similar outcomes with hemodialysis and peritoneal dialysis in patients with end-stage renal disease. Arch Intern Med 2011; 171: 110–118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Comparison of the impact of dialysis treatment type on patient survival [online ]: http://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT00510549 (25 September 2008, date last accessed)

- 46.Lameire N, Van Biesen W. Epidemiology of peritoneal dialysis: a story of believers and nonbelievers. Nat Rev Nephrol 2010; 6: 75–82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ledebo I, Kessler M, van Biesen W, et al. Initiation of dialysis-opinions from an international survey: report on the Dialysis Opinion Symposium at the ERA-EDTA Congress, 18 September 2000, Nice. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2001; 16: 1132–1138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Blake P. Proliferation of hemodialysis units and declining peritoneal dialysis use: an international trend. Am. J. Kidney Dis 2009; 54: 194–196 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.van Biesen W, Lameire N, Peeters P, et al. Belgium's mixed private/public health care system and its impact on the cost of end-stage renal disease. Int J Health Care Finance Econ 2007; 7: 133–148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Naito H. The Japanese health-care system and reimbursement for dialysis. Perit Dial Int 2006; 26: 155–161 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Chan MK, Lam SS, Chan PC, et al. Continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis (CAPD): experience with the first 100 patients in a Hong Kong centre. Int J Artif Organs 1987; 10: 77–82 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yu AW, Chau KF, Ho YW, et al. Development of the “peritoneal dialysis first” model in Hong Kong. Perit Dial Int 2007; 27 (Suppl 2): S53–S55 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Li PK, Chow KM. Peritoneal dialysis-first policy made successful: perspectives and actions. Am J Kidney Dis 2013; 62: 993–1005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Varughese S, John GT, Alexander S, et al. Pre-tertiary hospital care of patients with chronic kidney disease in India. Indian J Med Res 2007; 126: 28–33 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Cueto-Manzano AM. Peritoneal dialysis in Mexico. Kidney Int Suppl 2003; 83: S90–S92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Cueto-Manzano AM, Rojas-Campos E. Status of renal replacement therapy and peritoneal dialysis in Mexico. Perit Dial Int 2007; 27: 142–148 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Finkelstein FO, Abu-Aisha H, Najafi I, et al. Peritoneal dialysis in the developing world: recommendations from a symposium at the ISPD meeting 2008. Perit Dial Int 2009; 29: 618–622 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lo WK. Peritoneal dialysis in the far east—an astonishing situation in 2008. Perit Dial Int 2009; 29 (Suppl 2): S227–S229 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Baxter Healthcare Corp. Baxter Annual Report 2011. Baxter Healthcare Corp., 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 60.Just PM, Riella MC, Tschosik EN, et al. Economic evaluations of dialysis treatment modalities. Health Policy 2008; 86: 163–180 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Karopadi AN, Mason G, Rettore E, et al. The role of economies of scale in the cost of dialysis across the world: a macroeconomic perspective. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2014; 29: 885–892 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Golper TA, Guest S, Glickman JD, et al. Home dialysis in the new USA bundled payment plan: implications and impact. Perit Dial Int 2011; 31: 12–16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Abraham G, Pratap B, Sankarasubbaiyan S, et al. Chronic peritoneal dialysis in South Asia - challenges and future. Perit Dial Int 2008; 28: 13–19 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Schaefer F, Warady BA. Peritoneal dialysis in children with end-stage renal disease. Nat. Rev. Nephrol 2011; 7: 659–668 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Honda M, Warady BA. Long-term peritoneal dialysis and encapsulating peritoneal sclerosis in children. Pediatr. Nephrol 2010; 25: 75–81 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Verrina E, Edefonti A, Gianoglio B, et al. A multicenter experience on patient and technique survival in children on chronic dialysis. Pediatr Nephrol 2004; 19: 82–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Mitsnefes M, Stablein D. Hypertension in pediatric patients on long-term dialysis: a report of the North American Pediatric Renal Transplant Cooperative Study (NAPRTCS). Am J Kidney Dis 2005; 45: 309–315 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Borzych D, Rees L, Ha IS, et al. International Pediatric PD Network (IPPN). The bone and mineral disorder of children undergoing chronic peritoneal dialysis. Kidney Int 2010; 78: 1295–1304 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.North American Pediatric Renal Trials and Collaborative Studies. NAPRTCS 2011 annual dialysis report [online]. https://web.emmes.com/study/ped/annlrept/annualrept2011.pdf (28 April 2015, date last accessed)

- 70.Khan IH, Catto GR, Edward N, et al. Death during the first 90 days of dialysis: a case control study. Am J Kidney Dis 1995; 25: 276–280 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Foote C, Ninomiya T, Gallagher M, et al. Survival of elderly dialysis patients is predicted by both patient and practice characteristics. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2012; 27: 3581–3587 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Mendelssohn DC, Malmberg C, Hamandi B. An integrated review of “unplanned” dialysis initiation: reframing the terminology to “suboptimal” initiation. BMC Nephrol 2009; 10: 22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Ivarsen P, Povlsen JV. Can peritoneal dialysis be applied for unplanned initiation of chronic dialysis? Nephrol Dial Transplant 2014; 29: 2201–2206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Varughese S, Sundaram M, Basu G, et al. Percutaneous continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis (CAPD) catheter insertion—a preferred option for developing countries. Trop Doct 2010; 40: 104–105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Varughese S, Sundaram M, Basu G, et al. Percutaneous PD catheter insertion after past abdominal surgeries. Indian J Nephrol 2012; 22: 230–231 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Krediet RT, Lindholm B, Rippe B. Pathophysiology of peritoneal membrane failure. Perit Dial Int 2000; 20 (Suppl 4): S22–S42 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Justo P, Sanz AB, Egido J, et al. 3,4-Dideoxyglucosone-3-ene induces apoptosis in renal tubular epithelial cells. Diabetes 2005; 54: 2424–2429 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Johnson DW, Brown FG, Clarke M, et al. balANZ Trial Investigators. Effects of biocompatible versus standard fluid on peritoneal dialysis outcomes. J Am Soc Nephrol 2012; 23: 1097–1107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Kim S, Oh J, Kim S, et al. Benefits of biocompatible PD fluid for preservation of residual renal function in incident CAPD patients: a 1-year study. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2009; 24: 2899–2908 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]