Abstract

When reinforcers of different magnitudes are concurrently available, choice is greater for a large reinforcer; that choice can be reduced by delaying its delivery, a phenomenon called delay discounting and represented graphically by a delay curve in which choice is plotted as a function of delay to the large reinforcer. Morphine, administered acutely, can alter responding for large, delayed reinforcers. In this study, the impact of morphine tolerance, dependence and withdrawal on choice of delayed reinforcers was examined in 6 pigeons responding to receive a small amount of food delivered immediately or a larger amount delivered immediately or after delays that increased within sessions. Acutely, morphine decreased responding for the large reinforcer, and the effect was greater when morphine was administered immediately, rather than 6 hr, before sessions. During 8 weeks of daily administration, morphine produced differential effects across pigeons, shifting the delay curve downward in some and upward in others. In all pigeons, tolerance developed to the response rate-decreasing effects of morphine but not to its effects on delay discounting. When chronic morphine treatment was discontinued, rate of responding decreased in 4 pigeons, indicating the emergence of withdrawal; choice of the large reinforcer increased, regardless of delay, in all pigeons, an effect that persisted for weeks. These data suggest that chronic morphine administration has long-lasting effects on choice behavior, which might impact vulnerability to relapse in opioid abusers.

Keywords: delay discounting, morphine, tolerance, withdrawal, key peck, pigeon

Impulsive behaviors are thought to be important behavioral determinants of drug use, to be characteristic of substance-abusing individuals, and to develop as a consequence of drug use (de Wit, 2009). In delay-discounting procedures, which reflect one aspect of impulsive behavior, subjects choose between a small, immediately available reinforcer and a larger, delayed reinforcer; the two reinforcers are often qualitatively the same and vary only in magnitude. Subjects respond for the large reinforcer when there is little or no delay to its delivery; as the delay is increased, responding for the large reinforcer decreases and responding for the small reinforcer increases, an effect called delay discounting and represented graphically by a delay curve in which choice of the large reinforcer is plotted as a function of delay to its delivery. Both the amount of the reinforcer as well as delay to the large reinforcer can impact choice (Ainslie, 1974; Evenden & Ryan, 1999); while sensitivity to amount and delay is highly variable among subjects, delay functions are consistently hyperbolic.

A number of studies have reported that drug abuse is associated with increased discounting of delayed rewards. For example, opioid abusers discount delayed rewards at higher rates than healthy controls (Kirby, Petry & Bickel, 1999; Kirby & Petry, 2004; Madden, Petry, Badger & Bickel, 1997; Madden, Bickel & Jacobs, 1999). While increased discounting among opioid abusers might be a reflection of personality traits, drugs might directly increase discounting. Individuals currently using heroin discount monetary rewards at a significantly higher rate than abusers who have not used heroin for at least 14 days (Kirby & Petry, 2004), which is indicated by a steeper delay-discounting curve and suggests that increased discounting could be due to the direct effects of opioids; unfortunately, this conclusion is complicated by the use of another opioid, methadone, in some individuals in both groups of heroin abusers. This potential confound could be eliminated by studying the effects of opioids under other conditions. Several studies have shown increased discounting following acute administration of the µ opioid receptor agonist morphine (Kieres, Hausknecht, Farrar, Acheson et al., 2004; Pattij, Schetters, Janssen, Wiskerke et al., 2009; Pitts & McKinney, 2005). Although further work is needed to understand how morphine affects delay discounting when it is administered chronically, effects obtained when morphine is administered acutely suggest that discounting might increase during chronic morphine treatment and, thereby, contribute to continued drug abuse. These studies are important because chronic administration of morphine mimics the pattern of use among most opioid abusers.

The current study examined the effects of acute and chronic morphine administration in pigeons responding under a delay-discounting procedure with fixed delays (Evenden & Ryan, 1996); delays to the large reinforcer increased in predetermined increments within daily sessions. Changes in the delay-discounting function were determined during daily administration of morphine as well as after discontinuation of morphine. Response rates were also monitored to assess the development of tolerance to and dependence on morphine.

Method

Subjects

Six adult white Carneau pigeons (435–600 g) had unlimited access to water and grit in their home cage. Free-feeding weights for each pigeon were determined before the start of the experiment by averaging body weights obtained daily for 10 consecutive days in which pigeons had unlimited access to food (Purina Pigeon Checkers). Pigeons received food (Purina Pigeon Checkers) during experimental sessions, and supplemental food was provided in the home cage based on weights obtained before and after sessions. When body weights obtained before sessions were above 85% of the free-feeding weights and pigeons gained more than 5 g during sessions, supplemental food was not provided; when weight gain was ≤5 g during sessions, pigeons received 5–10 g of food in the home cage. When body weights obtained before sessions were at or below 85% of free-feeding weights, they received 10–20 g of food in the home cage, depending on how much weight they gained during sessions. Pigeons were housed individually in a temperature- and humidity-controlled vivarium under a 14 hour light/10 hour dark cycle. All pigeons had a history of responding for food under various schedules of reinforcement and, most recently, had received flunitrazepam in a previous delay-discounting experiment (Eppolito, France & Gerak, 2011); they had not received drug for two months before the current experiment. All animal care and experimental protocols were in accordance with the National Institutes of Health Guide to the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (National Academy of Sciences, 1996) and were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio.

Apparatus

Two self-contained operant conditioning chambers (BRS/LVE, Laurel, MD, USA) and two operant conditioning chambers (Med Associates, Inc., St. Albans, VT, USA) contained in sound-attenuating boxes (BRS/LVE, Laurel, MD, USA) were used; each pigeon was assigned to a specific experimental chamber for the duration of the study. Chambers were equipped with three translucent response keys that could be illuminated with red lights. An opening was centered below the response keys and allowed access to a food hopper; the opening was illuminated by a white light during presentation of the food hopper. A white house light was illuminated during delay periods. An interface connected chambers to a computer which controlled experimental events and collected data using MED-PC/Medstate Notation software (MED Associates Inc., East Fairfield, VT).

Procedure

Sessions were 95 min long and began with a 15-min timeout during which the chamber was dark and responses had no programmed consequence; the remaining 80 min were divided into five discrete, 16-minute cycles, which began with 2 forced trials followed by 10 choice trials (Eppolito, France & Gerak, 2011). The beginning of a trial was signaled by illumination of center key. During forced trials, one response on the center key extinguished that key light and illuminated one of the outer key lights whereas during choice trials both outer key lights were illuminated following a center key response. A single response on an illuminated outer key extinguished key lights and resulted in the immediate delivery of food or initiation of the delay followed by the delivery of food. The house light was illuminated during delays and extinguished immediately before food was delivered; the chamber was dark between delivery of the reinforcer and the start of the next trial. For each pigeon, one outer response key was associated with 4-s access to the food hopper and the other was associated with the 1.5 s access to the food hopper. This association was counterbalanced across pigeons and was maintained for each individual pigeon throughout the experiment. A second forced trial preceded choice trials to ensure that pigeons sampled the contingencies on both keys; the opposite outer key was illuminated after the response on the center key during the second forced trial, and the order in which the forced trials were presented varied randomly across sessions. The next trial began 60 s after a response on an outer, illuminated key. When the response requirement (one response on the center key and one response on an outer key) was not satisfied within 10 s, the trial ended and a 60-s timeout began. Failure to complete both forced trials ended the cycle and the chamber remained dark for the remainder of that cycle. During the 10 choice trials, a response on either outer key resulted in the delivery of food either immediately or after a delay. During the first cycle of the session, there was no delay between a response and delivery of the reinforcer. Beginning on the second cycle, there was a delay to the large reinforcer that was doubled from one cycle to the next; delays to the large reinforcer, which were determined empirically for individual pigeons, were 1, 2, 4 and 8 s for 1 pigeon, 2, 4, 8 and 16 s for 4 pigeons, and 6, 12, 24 and 48 s for 1 pigeon. Periodically (every 6–8 weeks) before chronic morphine administration, sessions were conducted during which all delays to the large reinforcer were removed and responses on both outer keys resulted in immediate access to the food hopper during choice trials. These sessions determined whether responding for the large reinforcer was controlled by delay, and not by the temporal organization of the session, and were otherwise not different from sessions with delays. Sessions without delays were conducted daily until pigeons responded >80% on the key associated with the large reinforcer during each cycle; delays were reintroduced during the next session.

Test sessions began when the following criteria were satisfied for 3 consecutive sessions: ≥90% of responses during the first cycle on the key associated with the large reinforcer; ≤20% of responses during the last cycle on the key associated with the large reinforcer; and at least 5 out of 10 choice trials completed during each cycle. On separate occasions, various doses of morphine were administered either immediately or 6 hr before sessions, and at least 3 sessions during which saline or sham injections were administered separated sessions during which morphine injections were given. If the testing criteria were not satisfied during each of the intervening sessions, additional training sessions were conducted until the testing criteria were satisfied for 3 consecutive days. Pigeons were weighed before and after sessions.

Thereafter, the effects of chronic morphine treatment on delay discounting were studied for 8 weeks (Table 1). On the first day of morphine administration, 10 mg/kg of morphine was given 6 hr before the session. This dose was selected because it was the largest dose that had no effect on the number of trials completed when given acutely 6 hr before sessions. Moreover, tolerance and dependence develop in pigeons receiving morphine 6 hr before sessions (France & Woods, 1990; Gauthier, Gerak, Bagley, Brockunier et al., 1998; Walker, Hawkins, Tiano, Picker et al., 1999). The daily dose of morphine was increased every 2 weeks in ½ log unit increments up to 100 mg/kg/day. During the final 2 weeks of daily morphine administration, two injections of 100 mg/kg were administered daily, one 6 hr before the session and the other 2.5 hr after the session. To test for the development of tolerance to morphine, a saline injection was given 6 hr before the session on the 13th day of chronic treatment with 10, 32 and 100 mg/kg/day of morphine (days 13, 27 and 41 since the first daily dose of morphine); the daily treatment dose was administered immediately before the session on those days. On day 43 of chronic treatment, a saline injection replaced the morphine injection 6 hr before the session to probe for signs of withdrawal (i.e., changes in body weight and disruptions in food-maintained responding). Because withdrawal signs were not evident in all pigeons, chronic treatment continued with an injection of 100 mg/kg of morphine administered 2.5 hr after the session on day 43. For the next 7 days, twice daily injections of 100 mg/kg were administered. On day 51 of chronic morphine treatment, a saline injection replaced the morphine injection 6 hr before the session to again probe for signs of withdrawal, which were not evident in any pigeon, and twice daily morphine administration continued for 7 more days. Morphine administration was discontinued after 57 days of chronic treatment. Signs of withdrawal, including disruptions in food-maintained responding, changes in the delay-discounting function, and weight loss, were monitored for 5 weeks.

Table 1.

Detailed timeline of experimental design.

| Experimental Phase |

Dose (mg/kg) morphine | Time of injection (relative to session) |

Day of chronic treatment |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Chronic |

10.0 | 6 hr before | 1–12 |

| 10.0 (probe for tolerance) | 0 hr before | 13 | |

| 10.0 | 6 hr before | 14 | |

| 32.0 | 6 hr before | 15–26 | |

| 32.0 (probe for tolerance) | 0 hr before | 27 | |

| 32.0 | 6 hr before | 28 | |

| 100.0 | 6 hr before | 29–40 | |

| 100.0 (probe for tolerance) | 0 hr before | 41 | |

| 100.0 | 6 hr before | 42 | |

| 0 (probe for withdrawal) | 6 hr before | ||

| 100.0 | 2.5 hr after | 43 | |

| 100.0 | 6 hr before | ||

| 100.0 | 2.5 hr after | 44–50 | |

| 0 (probe for withdrawal) | 6 hr before | ||

| 100.0 | 2.5 hr after | 51 | |

| 100.0 | 6 hr before | ||

| 100.0 | 2.5 hr after | 52–57 | |

| 0 (discontinuation) | 6 hr before | 58 | |

| Post-chronic | 0 (monitor withdrawal signs) | ||

Drugs

Morphine (Research Technology Branch, National Institute on Drug Abuse, Rockville, MD, USA) was dissolved in saline. Injections were administered intramuscularly in a volume of 1.0 ml/kg body weight.

Statistical analyses

Measures of delay discounting were determined by the percentage of responding on the key associated with the large reinforcer, calculated by dividing the number of responses emitted on that key by the total number of responses emitted on both outer keys and multiplying by 100. Data were included in the analyses of the delay-discounting function when at least 5 of the 10 choice trials were completed during each cycle. To determine rates of discounting before chronic morphine treatment, delay-discounting curves from 5 sessions immediately preceding the start of chronic treatment were averaged; only sessions during which testing criteria were satisfied were included. Straight lines were fit to delay-discounting curves of individual pigeons obtained during acute and chronic morphine treatment. Lines that did not significantly differ from 0 indicated that behavior was no longer under control of the delay associated with the large reinforcer (i.e., responses were for the large reinforcer or the small, immediately available reinforcer regardless of delay). Delay-discounting functions were compared across days by first adding the percentage of responses emitted on the key associated with the large reinforcer across the last 4 cycles (i.e., sums of Y values) for individual pigeons. Values obtained following discontinuation of chronic morphine treatment were plotted as a function of days since the last injection of morphine. When the sum of Y values equaled 400, all responses during that session were emitted on the key associated with the large reinforcer and a value of 0 indicated that all responses were emitted on the key associated with the small reinforcer. When fewer than 25 trials were completed during the session, sums of Y values were not plotted. Effects on body weight were determined by comparing weights obtained immediately before sessions following discontinuation of morphine to those obtained before the session on the last day of chronic morphine treatment; the resulting difference scores were analyzed by one-way analysis of variance. Data were analyzed using GraphPad 5.01 Software (La Jolla, CA, USA, www.graphpad.com). Statistical tests were deemed significant when p < 0.05.

Results

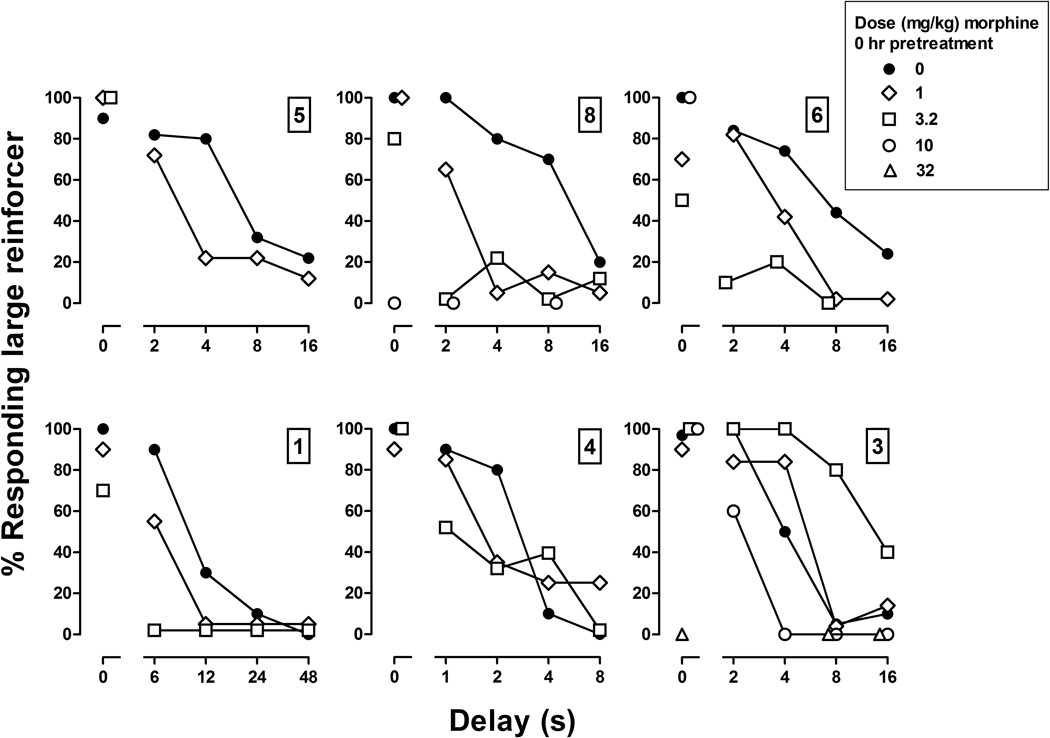

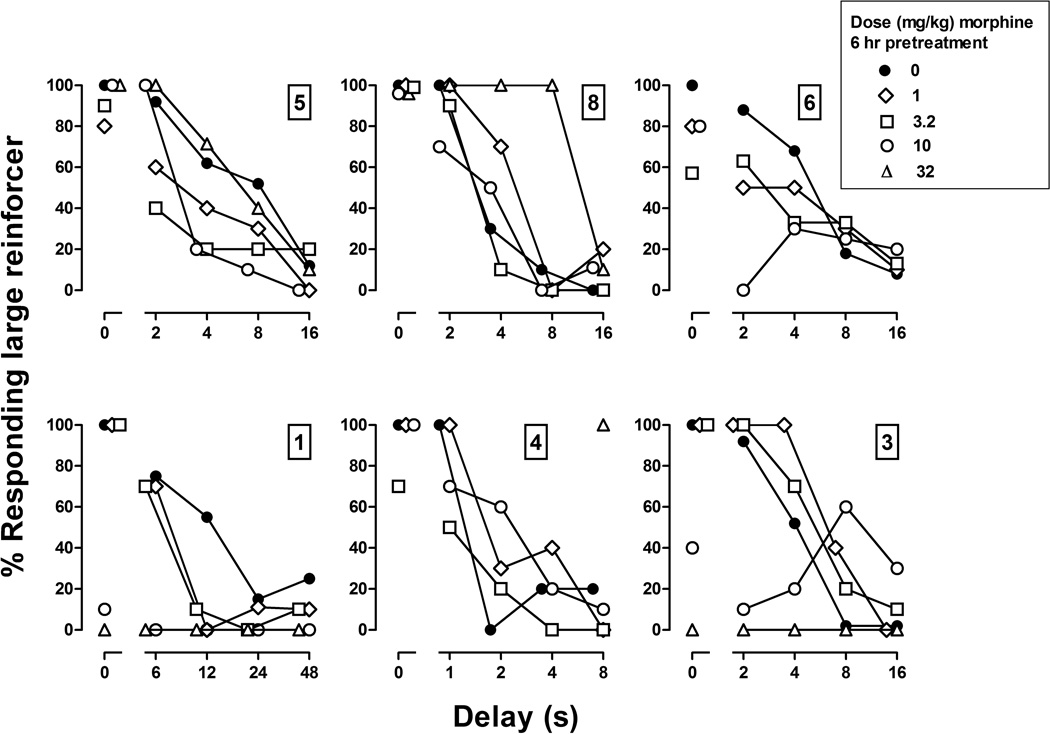

In the absence of drug, responding for the large reinforcer was greatest at the beginning of the session, when there was no delay to its delivery and when the delay was small (1–6 s). There was a delay-dependent decrease in responding for the large reinforcer with pigeons responding, on average, 98% on the key associated with the large reinforcer during the first cycle and 11% during the last cycle of the session (Figures 1 and 2, filled circles). When saline was administered, pigeons rarely failed to complete all 10 choice trials within each cycle (Tables 2 and 3).

Figure 1.

Acute effects of morphine administered immediately before sessions in 6 pigeons. Numbers above ordinates indicate the identification numbers for subjects. Abscissae: delay in seconds to the large reinforcer. Ordinates: percentage of responses emitted on the key associated with the large reinforcer.

Figure 2.

Acute effects of morphine given 6 hr before sessions in 6 pigeons. Numbers above ordinates indicate the identification numbers for subjects. Abscissae: delay in seconds to the large reinforcer. Ordinates: percentage of responses emitted on the key associated with the large reinforcer.

Table 2.

Effects of morphine administered immediately before sessions on the number of trials completed as a function of delay. Data for individual pigeons and the group mean (± 1 S.E.M.) are presented.

| Number of trials completed | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pigeon ID | ||||||||

| Dose (mg/kg) morphine |

Delay (s) | 5 | 8 | 6 | 1 | 4 | 3 | Group Data |

| 0 | 0 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10(0) |

| x | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10(0) | |

| 2x | 9 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 9.8(0.2) | |

| 4x | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10(0) | |

| 8x | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10(0) | |

| 1 | 0 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10(0) |

| x | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10(0) | |

| 2x | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10(0) | |

| 4x | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10(0) | |

| 8x | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 9 | 9.8(0.2) | |

| 3.2 | 0 | 8 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 9.7(0.3) |

| x | 2 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 8.7(1.3) | |

| 2x | 0 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 8.3(1.7) | |

| 4x | 0 | 10 | 6 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 7.7(1.7) | |

| 8x | 0 | 10 | 0 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 6.7(2.1) | |

| 10 | 0 | 0 | 10 | 10 | 0 | 0 | 10 | 5(2.2) |

| x | 0 | 10 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 10 | 3.2(2.1) | |

| 2x | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 10 | 1.7(1.7) | |

| 4x | 0 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 10 | 2.5(1.7) | |

| 8x | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 10 | 2.2(1.6) | |

| 32 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 9 | 1.5(1.5) |

| x | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 0.7(0.7) | |

| 2x | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0.5(0.5) | |

| 4x | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 1.0(1.0) | |

| 8x | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 0.8(0.8) | |

Table 3.

Effects of morphine administered 6 hr before sessions on the number of trials completed as a function of delay. Data for individual pigeons and the group mean (± 1 S.E.M.) are presented.

| Number of trials completed | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dose (mg/kg) morphine |

Delay (s) |

Pigeon ID | Group Data |

|||||

| 5 | 8 | 6 | 1 | 4 | 3 | |||

| 0 | 0 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10(0) |

| x | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10(0) | |

| 2x | 10 | 10 | 10 | 8 | 10 | 10 | 9.6(0.3) | |

| 4x | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10(0) | |

| 8x | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10(0) | |

| 1 | 0 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10(0) |

| x | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10(0) | |

| 2x | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10(0) | |

| 4x | 10 | 10 | 10 | 9 | 10 | 5 | 9(0.8) | |

| 8x | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 9 | 10 | 9.8(0.2) | |

| 3.2 | 0 | 10 | 10 | 7 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 9.5(0.5) |

| x | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10(0) | |

| 2x | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10(0) | |

| 4x | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10(0) | |

| 8x | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10(0) | |

| 10 | 0 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10(0) |

| x | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10(0) | |

| 2x | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10(0) | |

| 4x | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10(0) | |

| 8x | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10(0) | |

| 32 | 0 | 8 | 10 | 2 | 10 | 4 | 10 | 7.3(1.4) |

| x | 9 | 10 | 0 | 10 | 0 | 10 | 6.5(2.1) | |

| 2x | 7 | 10 | 0 | 10 | 0 | 10 | 6.2(2.0) | |

| 4x | 10 | 10 | 0 | 10 | 1 | 10 | 6.8(2.0) | |

| 8x | 10 | 10 | 0 | 10 | 5 | 10 | 7.5(1.7) | |

When administered immediately before sessions, morphine shifted the delay-discounting function leftward and downward (Figure 1). In pigeons 8, 6, and 1, at least one dose of morphine decreased choice for the large reinforcer when both reinforcers were delivered without delay (Figure 1, points above 0), regardless of which key was associated with the large reinforcer (right key in pigeon 8; left key in the other two pigeons). After administration of 3.2 mg/kg, those 3 pigeons responded predominantly on the key associated with the small reinforcer when delivery of the large reinforcer was delayed by an length of time (i.e., delay >0), and line analyses of the delay curve obtained in each of those three pigeons revealed that the slope did not differ from 0 (Figure 1, squares). In pigeon 3, a dose of 3.2 mg/kg of morphine increased responding for the large reinforcer, shifting the curve rightward and upward, while a larger dose (10 mg/kg) produced the opposite effect, shifting the curve leftward and downward (Figure 1, circles). Although the effective dose varied across pigeons, morphine shifted the delay-discounting curve leftward and downward in all 6 pigeons. Moreover, pigeon 3, who was least sensitive to the effects of morphine on delay discounting, was also the least sensitive to its effects on response rate, as indicated by the number of trials completed (Table 2). When administered immediately before sessions, the effects of morphine on number of trials completed tended to be greater later in the session, and this effect occurred at different doses across pigeons (Table 2).

Before chronic morphine treatment began, the acute effects of morphine given 6 hr before sessions were also examined; this interval between morphine administration and the start of the session was used when morphine was administered chronically. Morphine altered the delay-discounting curve in each pigeon, although the effect was not clearly dose dependent and the curve was not consistently shifted in the same direction. For example, in pigeon 5, small doses of morphine shifted the curve leftward and downward (Figure 2, upper left panel, diamonds, squares and circles); however, 32 mg/kg did not shift the delay-discounting curve, as compared to the curve obtained following administration of saline (Figure 2, triangles). That dose had different effects in other pigeons, shifting the curve rightward in pigeon 8 and shifting it downward in pigeons 1 and 3 such that all responses during the session were emitted on the key associated with the small reinforcer. Line analyses indicated that the slope of delay curves did not differ from 0 after 10 mg/kg of morphine in pigeons 6, 1 and 3 and after 32 mg/kg in pigeons 8, 1 and 3. The effects of morphine on the number of trials completed were smaller in every pigeon when it was given 6 hr before sessions, as compared to its effects when it was given immediately before sessions (compare Tables 2 and 3). In 3 of the 6 pigeons (8, 3, and 1), 32 mg/kg of morphine did not decrease the number of trials completed; 2 other pigeons (6 and 4) completed significantly fewer trials 6 hr after receiving 32 mg/kg.

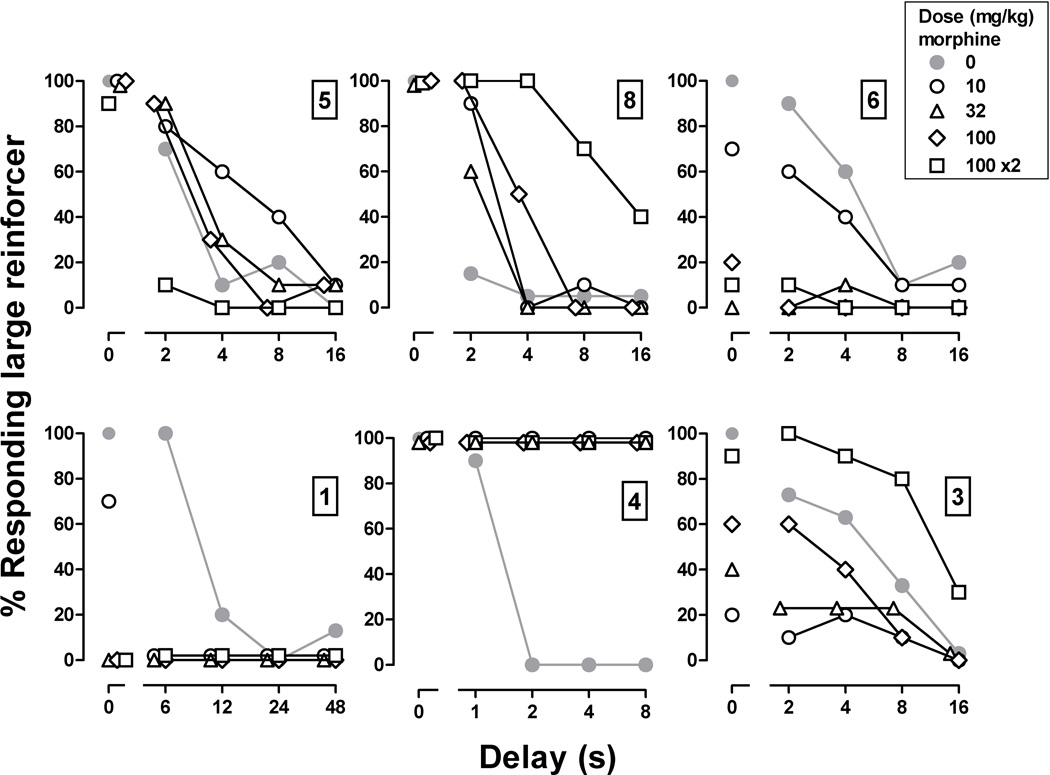

Delay-discounting functions were differentially changed in individual pigeons over 8 weeks of daily morphine administration. In pigeons 5, 8, 1 and 3, effects obtained on the first day of chronic morphine treatment were similar to those obtained when 10 mg/kg of morphine was studied acutely 6 hr before sessions (Figure 2, circles); in the other 2 pigeons, the delay curve obtained on the first day of chronic morphine treatment was shifted upward, as compared to the curve obtained when 10 mg/kg was given acutely 6 hr before sessions. For pigeons 5 and 6, delay curves during chronic administration of 10 mg/kg/day were similar to curves obtained following administration of saline. However, when the daily dose was increased to 32 mg/kg in pigeon 6 and to 200 mg/kg in pigeon 5, delay curves were shifted downward in both pigeons; once these effects emerged, they did not change for the remainder of the chronic treatment period even when the morphine dose increased (Figure 3). For pigeons 1 and 4, maximal effects were obtained on the first day of chronic morphine treatment, although the effects were in opposite directions (downward shift in pigeon 1 and upward shift in pigeon 4); these effects of morphine also did not change during chronic treatment even with increasing doses of morphine (Figure 3). For pigeons 8 and 3, effects were evident when chronic treatment began with the delay curve shifting upward in pigeon 8 and shifting downward in pigeon 3 on the first day; however, these effects of morphine changed over the course of chronic treatment with the delay curve shifting upward as the morphine dose increased. Because the curves were shifted in opposite directions initially, these changes represented an enhancement of the effect in pigeon 8 and a reduction in pigeon 3.

Figure 3.

Effects of daily morphine treatment on delay-discounting functions in 6 pigeons. Filled gray circles were obtained during a single session prior to the beginning of daily morphine administration. Open symbols were obtained on the 7th of 14 days at each dose when morphine was given 6 hr before sessions. Abscissae: delay in seconds to the large reinforcer. Ordinates: percentage of responses emitted on the key associated with the large reinforcer.

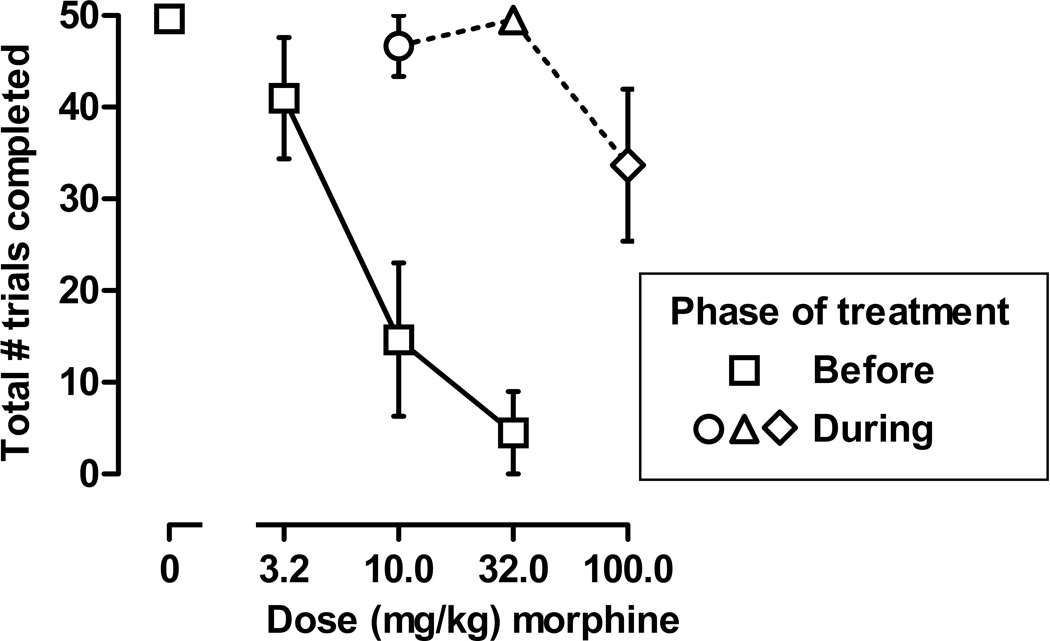

The daily dose of morphine, given 6 hr before sessions, did not alter the number of trials completed at any time with pigeons consistently finishing 9–10 trials per cycle throughout the 8 weeks. Before chronic treatment, 10 and 32 mg/kg of morphine, given immediately before sessions, markedly decreased the number of trials completed (Figure 4, squares). In fact, only one pigeon (3) responded during choice trials after receiving a dose of 32 mg/kg, and that pigeon completed only 27 of 50 trials. In contrast, when 10 and 32 mg/kg of morphine were given immediately before sessions on days 13 and 27, respectively, of chronic treatment, pigeons completed >90% of the trials, and a larger dose of morphine (100 mg/kg), given immediately before the session on day 41, produced only a modest decrease in number of trials completed (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Effects of an acute injection of morphine on the total number of trials completed before (squares) and during chronic morphine treatment. The circle represents the effects of 10 mg/kg of morphine determined on the 13th of 14 days of chronic treatment with 10 mg/kg; the triangle represents the effects of 32 mg/kg of morphine determined on the 13th of 14 days of chronic treatment with 32 mg/kg/day (27 total days of morphine administration); and the diamond represents the effects of 100 mg/kg of morphine determined on the 13th of 14 days of chronic treatment with 100 mg/kg/day (41 total days of morphine administration). Morphine was administered immediately before sessions. Abscissae: dose (mg/kg) of morphine. Ordinates: mean total number of trials completed during the session (± 1 SEM).

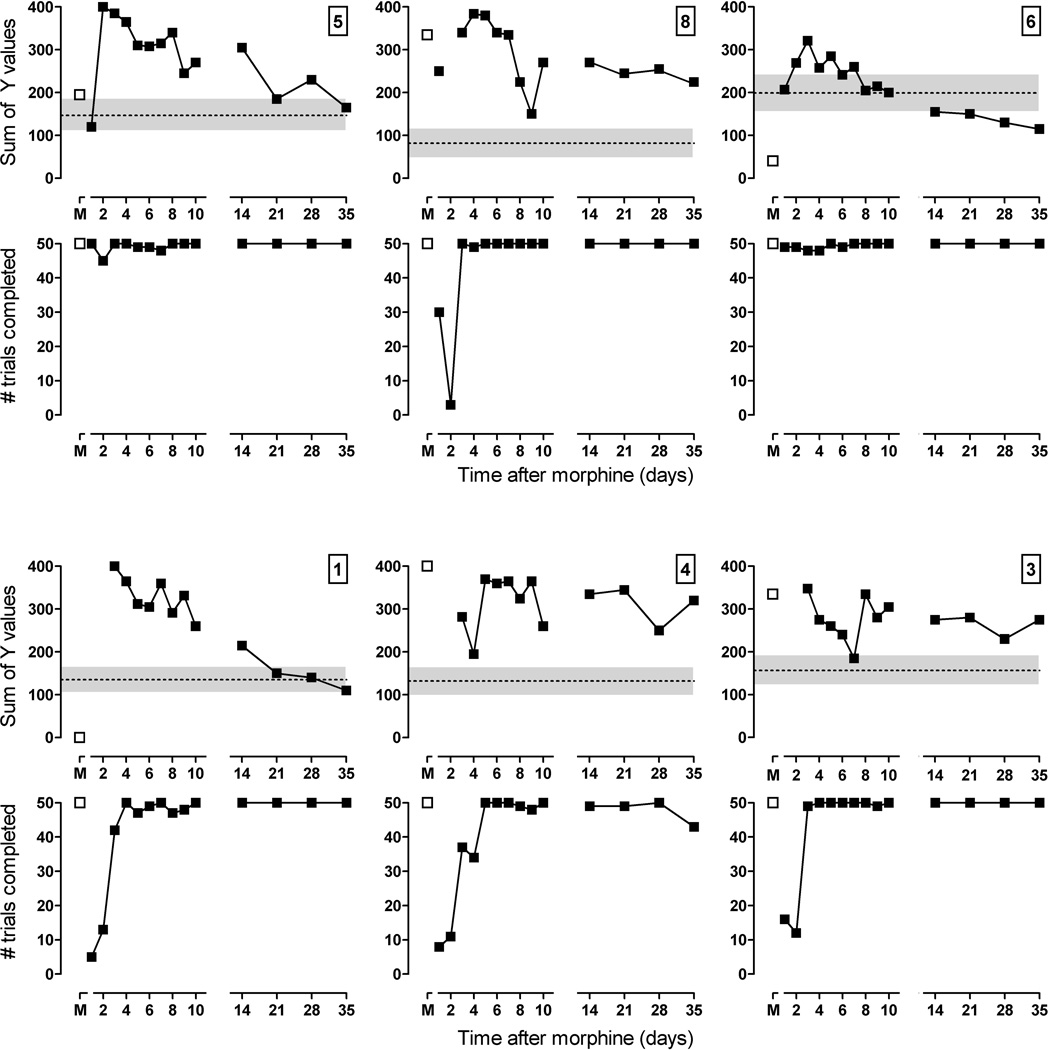

As shown by the open squares in the upper panels of Figure 5, on the last day of morphine treatment, the sum of the Y values was more than 1 standard deviation from the mean score of 5 sessions determined before chronic morphine treatment. For pigeons 5, 8, 4 and 3, the sum of Y values increased, indicating that the delay-discounting curve was shifted rightward and upward (i.e., increased responding for the large reinforcer); for pigeons 6 and 1, the sum of Y values decreased, indicating that the curve was shifted downward (i.e., decreased responding for the large reinforcer). Within 24–48 hr of discontinuation of morphine treatment, the number of trials completed was markedly decreased in 4 of the 6 pigeons, and delay-discounting curves could not be obtained. The filled squares in the lower panels of Figure 5 reveal that, 3 days after the last injection of morphine, all pigeons completed at least half of the trials, and on that day, responding on the key associated with the large reinforcer increased for all pigeons, as compared to responding for the large reinforcer prior to chronic treatment. Thus, while chronic morphine treatment altered the delay-discounting curve differently across pigeons, curves obtained following discontinuation were remarkably similar, with pigeons responding predominantly on the key associated with the large reinforcer regardless of delay. These changes in the delay function persisted for some time after the last injection of morphine and were still evident for 3 pigeons (8, 4 and 3) 5 weeks later.

Figure 5.

Effects of discontinuing daily morphine administration on delay discounting in 6 pigeons. Upper panels show the sums of Y values determined from the last 4 cycles of delay-discounting functions; lower panels show the total numbers of trials completed during sessions. Open symbols above M were obtained on the last day of chronic morphine treatment and filled symbols were obtained on subsequent days. Dashed lines and shaded areas represent the average sum of Y values (± 1 S.D.) calculated for each pigeon over the last 5 saline sessions before the beginning of chronic morphine treatment. Abscissa: days since the last dose of morphine. Ordinate: sum of Y values for percentage of responses for the large reinforcer (± 1 SEM).

Discontinuation of chronic morphine treatment also significantly decreased body weight in all pigeons (Table 4). Pigeons were maintained between 84% and 91% of their free-feeding weights before and during chronic morphine treatment, and their average weight over the last 3 days of daily morphine was 503.0±19.3 g. Significant weight loss was first evident 2 days after the last injection of morphine, when they lost, on average, 32.3±8.1 g, and was even greater 3 days after the last injection of morphine, when they lost 36.5±9.3 g, despite receiving an amount of food in the home cage that was sufficient to maintain body weight prior to discontinuation of chronic morphine treatment. Six days after the last injection of morphine, body weights were no longer different from those obtained during chronic morphine treatment. There seemed to be a relationship between the magnitude of weight loss and persistence of changes in delay function following discontinuation of morphine treatment; pigeons that lost more weight needed more time for the delay curve to return to control.

Table 4.

Body weights obtained during the last 3 days of morphine treatment (treatment days 55–57) and immediately before and after discontinuation of daily morphine administration. Data for individual pigeons and the group mean (± 1 S.E.M.) are presented.

| Pigeon ID | Group Mean |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5 | 8 | 6 | 1 | 4 | 3 | ||

| 85% free-feeding weight | 435 | 451 | 575 | 475 | 515 | 481 | 488.7(20.6) |

| Treatment Day 55 | 447 | 474 | 569 | 487 | 522 | 493 | 498.7(17.3) |

| Treatment Day 56 | 443 | 474 | 569 | 482 | 547 | 489 | 500.7(19.4) |

| Treatment Day 57 | 445 | 475 | 567 | 483 | 587 | 510 | 511.2(22.6) |

| Discontinuation Day 1 | 432 | 470 | 554 | 474 | 566 | 483 | 496.8(21.3) |

| Discontinuation Day 2 | 434 | 446 | 545 | 460 | 520 | 468 | 478.8(17.9) |

| Discontinuation Day 3 | 433 | 440 | 545 | 455 | 510 | 465 | 474.7(17.9) |

| Discontinuation Day 4 | 444 | 451 | 552 | 465 | 511 | 476 | 483.2(16.8) |

| Discontinuation Day 5 | 443 | 455 | 562 | 474 | 515 | 479 | 488.0(17.9) |

| Discontinuation Day 6 | 450 | 464 | 568 | 482 | 523 | 483 | 495.0(17.7) |

| Discontinuation Day 7 | 457 | 460 | 564 | 484 | 539 | 485 | 498.2(17.8) |

Discussion

When administered acutely or chronically, morphine altered delay discounting. While these effects were somewhat variable across pigeons, some trends emerged. For example, when morphine was administered acutely immediately before sessions, the delay-discounting curve usually was shifted leftward and downward; when the delay to delivery of the large reinforcer was short, responding on the key associated with the small reinforcer increased in all pigeons after administration of at least one dose of morphine (i.e., the largest dose that did not decrease the number of trials completed). In contrast, when saline was administered, responding for the large reinforcer varied according to delay to its delivery, as evidenced by an orderly switch in responding from the key associated with the large reinforcer to the key associated with the small reinforcer as delays increased across cycles as well as nearly exclusive responding for the large reinforcer when there was no delay for all cycles (Eppolito et al., 2011). Thus, the overall effect of morphine administered acutely in pigeons seems to be an increase in delay discounting, which is consistent with effects obtained in rats (Kieres et al., 2004; Pattij et al., 2009; Pitts & McKinney, 2005); however, the decrease in responding on the key associated with the large reinforcer when there was no delay to either reinforcer suggests that, at least in some subjects, factors other than delay might also contribute to this effect of morphine, such as a change in stimulus control.

Effects obtained when morphine was given 6 hr before sessions were more variable as compared with those obtained when morphine was given immediately before sessions. The delay-discounting curve was shifted leftward and downward in 5 of the 6 pigeons, although the effect was not dose dependent in 2, and was shifted to the right in the 6th pigeon. Variability among pigeons persisted when morphine was administered daily. For example, by the last day of chronic morphine treatment, 2 pigeons were responding predominantly for the small reinforcer, regardless of delay to delivery of the large reinforcer, whereas in the other 4 pigeons, responding increased on the key associated with the large reinforcer, as compared with responding prior to chronic morphine treatment. In addition, the manner in which delay discounting curves changed over the course of chronic morphine treatment varied across subjects with changes evident within the first few days of chronic morphine treatment in some pigeons and emerging only near the end of chronic treatment in others. Despite this variability across pigeons, the effects were persistent in most pigeons; once an effect emerged, it did not change for the remainder of chronic morphine treatment. In other words, tolerance did not appear to develop to the effects of morphine on delay discounting.

There are a number of reasons why tolerance might not develop to some effects of morphine. One possibility is that either the morphine dose, frequency of administration, or duration of morphine administration were not sufficient; however, these dosing conditions were selected because previous studies have demonstrated the development of significant tolerance to the rate-decreasing effects of morphine when once daily injections were given (10 mg/kg for 1 week, 32 mg/kg for 1 week, and 100 mg/kg for at least 2 weeks; France & Woods, 1985; Gauthier et al., 1998). More importantly, in the current study, tolerance clearly developed to the effects of morphine on number of trials completed, which were markedly decreased by 32 mg/kg before chronic morphine treatment and unchanged during chronic treatment (Figure 4). Thus, these dosing conditions, which were sufficient to produce marked tolerance to one effect of morphine, did not produce tolerance to the effects of morphine on delay discounting, indicating that inadequate dosing conditions do not account for the apparent lack of tolerance to morphine. Although it is possible that modest tolerance developed to effects on discounting which could not be detected with the experimental conditions used in the current study, the difference is substantial between tolerance that developed to the rate-decreasing effects and any possible tolerance that developed to effects on discounting, suggesting that different mechanisms might account for these two effects. It is well documented that tolerance develops to all effects of morphine that are mediated by µ opioid receptors, albeit at different rates (France & Woods, 1985; Gauthier et al., 1998). That tolerance did not appear to develop to the effects of morphine on delay discounting despite clear evidence for tolerance to another effect might suggest that behavioral factors contribute to these persistent effects, such as increased perseveration or decreased behavioral flexibility.

Another consequence of chronic morphine treatment is the development of dependence and the emergence of a withdrawal syndrome when chronic morphine treatment is terminated. In the current study, dependence developed to morphine, as evidenced by the disruptions in food-maintained responding and decreased body weights 2 and 3 days after the last injection of morphine; these signs characteristically emerge when chronic morphine treatment is terminated (Gellert & Sparber, 1977; Holtzman & Villarreal, 1973). During morphine withdrawal, there was also a change in the delay-discounting curve, as compared to curves obtained before chronic morphine treatment, with the curve shifted upward in all 6 pigeons, regardless of the effects obtained during chronic morphine treatment; for example, pigeons 6 and 1 responded on the key associated with the small reinforcer and pigeons 8 and 3 responded on the key associated with the large reinforcer during chronic morphine treatment. Thus, withdrawal from morphine consistently increased responding for the large reinforcer across delays and in all subjects. The duration of this effect varied among individual pigeons; it lasted for at least 1 week in all pigeons and was still evident 5 weeks after the last injection morphine in 3 subjects. While the time course for many withdrawal signs is short, with peak effects emerging within 2–3 days and those effects no longer evident by 7 days since the last morphine dose, some signs have been shown to persist for weeks (Becker, Gerak, Koek & France, 2008; Gerak, Galici & France, 2009). These lingering withdrawal signs might contribute to relapse that occurs long after most withdrawal signs are gone. In these pigeons, opioid withdrawal decreases discounting, suggesting a decrease in this aspect of impulsivity; thus, it might be the persistence of withdrawal signs or a general disruption in sensitivity to scheduled consequences (i.e., delay to delivery of reinforcers), rather than a specific change in impulsivity, that increases the likelihood of relapse in opioid abusers.

In summary, morphine altered delay discounting when it was given acutely or chronically; these effects were generally consistent within pigeons, although the direction of these effects varied across pigeons. Tolerance developed to the rate-decreasing effects of morphine in all 6 pigeons and it did not appear to develop to the effects of morphine on delay discounting in any pigeon. Dependence also developed during chronic morphine treatment, as evidenced by the emergence of withdrawal signs when morphine administration was discontinued. One effect that emerged in all pigeons upon discontinuation of morphine was an increase in responding for the large reinforcer that persisted for weeks. Additional studies are needed to determine how long-lasting withdrawal signs and an apparent decrease in sensitivity to delayed reinforcers might contribute to effects obtained long after opioid use is terminated.

Acknowledgments

Charles P. France is supported by a Senior Scientist Award DA 017918.

Contributor Information

Amy K. Eppolito, Department of Pharmacology, University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio.

Charles P. France, Departments of Pharmacology and Psychiatry, University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio.

Lisa R. Gerak, Department of Pharmacology, University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio..

References

- Ainslie GW. Impulse control in pigeons. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior. 1974;21:485–489. doi: 10.1901/jeab.1974.21-485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker GL, Gerak LR, Koek W, France CP. Antagonist-precipitated and discontinuation-induced withdrawal in morphine-dependent rhesus monkeys. Psychopharmacology. 2008;201:373–382. doi: 10.1007/s00213-008-1293-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Wit H. Impulsivity as a determinant and consequence of drug use: a review of underlying processes. Addiction Biology. 2009;14:22–31. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-1600.2008.00129.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eppolito AK, France CP, Gerak LR. Effects of acute and chronic flunitrazepam on delay discounting in pigeons. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior. 2011;95:163–174. doi: 10.1901/jeab.2011.95-163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evenden JL, Ryan CN. The pharmacology of impulsive behaviour in rats: the effects of drugs on response choice with varying delays of reinforcement. Psychopharmacology. 1996;128:161–170. doi: 10.1007/s002130050121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evenden JL, Ryan CN. The pharmacology of impulsive behaviour in rats VI: the effects of ethanol and selective serotonergic drugs on response choice with varying delays of reinforcement. Psychopharmacology. 1999;146:413–421. doi: 10.1007/pl00005486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- France CP, Woods JH. Effects of morphine, naltrexone and dextrorphan in untreated and morphine-treated pigeons. Psychopharmacology. 1985;85:377–382. doi: 10.1007/BF00428205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- France CP, Woods JH. Discriminative stimulus effects of opioid agonists in morphine-dependent pigeons. The Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 1990;254:626–632. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gauthier CA, Gerak LR, Bagley JR, Brockunier LL, France CP. The rate-decreasing effects of fentanyl derivatives in pigeons before, during and after chronic morphine treatment. Psychopharmacology. 1998;137:67–73. doi: 10.1007/s002130050594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gellert VF, Sparber SB. A comparison of the effects of naloxone upon body weight loss and suppression of fixed-ratio operant behavior in morphine-dependent rats. The Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 1977;201:44–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerak LR, Galici R, France CP. Self administration of heroin and cocaine in morphine-dependent and morphine-withdrawn rhesus monkeys. Psychopharmacology. 2009;204:403–411. doi: 10.1007/s00213-009-1471-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holtzman SG, Villarreal JE. Operant behavior in the morphine-dependent rhesus monkey. The Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 1973;184:528–541. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kieres AK, Hausknecht KA, Farrar AM, Acheson A, de Wit H, Richards JB. Effects of morphine and naltrexone on impulsive decision making in rats. Psychopharmacology. 2004;173:167–174. doi: 10.1007/s00213-003-1697-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirby KN, Petry NM. Heroin and cocaine abusers have higher discount rates for delayed rewards than alcoholics or non-drug-using controls. Addiction. 2004;99:461–471. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2003.00669.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirby KN, Petry NM, Bickel WK. Heroin addicts have higher discount rates for delayed rewards than non-drug-using controls. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General. 1999;128:78–87. doi: 10.1037//0096-3445.128.1.78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madden GJ, Bickel WK, Jacobs EA. Discounting of delayed rewards in opioid-dependent outpatients: exponential or hyperbolic discounting functions? Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 1999;7:284–293. doi: 10.1037//1064-1297.7.3.284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madden GJ, Petry NM, Badger GJ, Bickel WK. Impulsive and self-control choices in opioid-dependent patients and non-drug-using control participants: drug and monetary rewards. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 1997;5:256–262. doi: 10.1037//1064-1297.5.3.256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pattij T, Schetters D, Janssen MC, Wiskerke J, Schoffelmeer AN. Acute effects of morphine on distinct forms of impulsive behavior in rats. Psychopharmacology. 2009;205:489–502. doi: 10.1007/s00213-009-1558-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pitts RC, McKinney AP. Effects of methylphenidate and morphine on delay-discounting functions obtained within sessions. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior. 2005;83:297–314. doi: 10.1901/jeab.2005.47-04. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker EA, Hawkins ER, Tiano MJ, Picker MJ, Dykstra LA. Discriminative stimulus effects of nalbuphine in nontreated and morphine-treated pigeons. Pharmacology, Biochemisty and Behavior. 1999;64:445–448. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(99)00086-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]