Abstract

Introduction

Management of the immunosuppressed patient with diverticular disease remains controversial. We report the largest series of colon cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy and hospitalized for acute diverticulitis, to determine whether recent treatment with systemic chemotherapy is associated with increased risk for/increased severity of recurrent diverticulitis.

Methods

Retrospective cohort study of adult patients hospitalized for an initial episode of acute colonic diverticulitis at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, 1988–2004. Outcomes in patients receiving systemic chemotherapy within one month of admission for diverticulitis (“Chemo”) were compared to outcomes of patients not receiving chemotherapy within the past month (“No-chemo”).

Results

A total 131 patients met inclusion criteria. Chemo patients did not differ significantly from No-chemo group in terms of severity of acute diverticulitis at index admission (13.2% vs. 4.4%, respectively, p=0.12), resumption of chemotherapy (median 2 months), failure of non-operative management (13.2% vs 4.4%, respectively, p=0.12), frequency of recurrence (20.5% vs 18.55), hospital length of stay (p=0.08), and likelihood of interval resection (24.0% vs. 16.2%, respectively, p=0.39). Chemo patients recurred with more severe disease, were more likely to undergo emergent surgery (75.0% vs. 23.5%, respectively, p=0.03), and were more likely to be diverted (100.0% vs. 25.0%, respectively, p=0.03). Chemo patients were significantly more likely to incur a postoperative complication (100% vs 9.1% p <0.01) following interval resection. Overall mortality was significantly higher in the Chemo vs. No-chemo group. Median survival in Chemo patients was 3.4 years; in No-chemo patients, median survival was not reached at 10 years

Conclusion

Our data do not support routine elective surgery for acute diverticulitis in patients receiving chemotherapy. Nonoperative management in the acute or interval setting appears preferable whenever possible.

Keywords: Colon cancer, Interval resection, Immunosuppression, Recurrence, Morbidity

INTRODUCTION

Colonic diverticular disease affects approximately 25% of the general population, with an increased prevalence in Western and industrialized countries, and in older adults[1–6]. Approximately 15% of patients with diverticulosis will eventually develop diverticulitis [7, 8]. Most episodes of diverticulitis involve only mild colonic inflammation that resolves with oral antimicrobial therapy and dietary modification. However, complicated diverticulitis ensues in 10% to 15% of cases, leading to perforation and abscess formation or, in severe instances, secondary fecal peritonitis, abdominal sepsis, and death [9, 10]. Following an initial episode of diverticulitis managed non-operatively, recurrence rates range from 13% to 40% [11–16]. When considering an interval segmental resection, the risk of subsequent recurrence and related complications must be assessed. Recent data suggests that there is a relatively low risk of recurrence following a single episode of diverticulitis, and a low risk of emergent surgical intervention. Therefore, traditional indications for interval resection have been relaxed [12, 17, 18].

Traditionally, the immunosuppressed (IMS) patient has been considered at increased risk of complicated and recurrent diverticulitis. Several series report increased morbidity and mortality from acute diverticulitis in IMS patients, and a high likelihood that non-operative management (NOM) will fail. [17, 19, 20]. As a result, some authors have argued for interval resection following an initial episode of diverticulitis in IMS patients [4, 17, 21, 22] [23]. However, these studies are limited by small sample sizes, variable types of immunosuppression, and a lack of follow-up beyond the initial hospitalization for diverticulitis. In particular, there has been no comparison of risk or severity of recurrence in cancer patient who are on chemotherapy (Chemo) to those who are not (No-chemo). Patients with cancer have dysregulation of their immune system. When we discuss the issue of immunity in cancer patients, we should consider other contributing factors which could influence result such as type of cancer, use of chemotherapeutic agents, stem cell transplantation, use of corticosteroids and radiation therapy. As a result, it is very difficult to differentiate between immunosuppressed and immunocompetent patients in this diverse population. Interval resection decreases the risk of recurrent diverticulitis; however, major abdominal surgery exposes patients to morbidity and potential interruption of life-prolonging chemotherapy. We studied the immediate and long-term outcomes of patients hospitalized for acute diverticulitis who were actively receiving systemic chemotherapy, in the hope that these data may help in clinical decision-making for cancer patients experiencing an episode of acute diverticulitis. Our primary aim was to assess whether recent systemic chemotherapy is associated with an increased severity in presentation of, and morbidity and mortality from, acute diverticulitis. Our secondary aim was to assess whether systemic chemotherapy is associated with a greater likelihood of, and increased severity of, recurrence [17, 19, 20, 24]..

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This was a retrospective cohort study of adult (age >18 years) patients hospitalized with an initial episode of acute colonic diverticulitis at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (MSKCC) from 1988–2004. All patients with a primary episode of acute diverticulitis who were treated at MSKCC were included in the study. For the occasional patient who was taken to the operating room without prior imaging, all episodes were confirmed by imaging or operative findings. Patients were initially identified using the codes for diverticulitis (562.11 and 562.13) as specified in the International Classification for Disease, 9th and 10th revision. The diagnosis for each patient was subsequently confirmed based on computed tomography findings or operative pathology. Patients with prior episodes of diverticulitis, either at our hospital or elsewhere, were excluded from the study. The primary independent variable was recent exposure to systemic chemotherapy; patients who received systemic chemotherapy within one month of admission for diverticulitis (Chemo group) were compared to patients who had not (No-chemo group). Exposure to chemotherapy greater than one month prior to the episode of diverticulitis was considered insufficient to cause immunosuppression [25–27], and such patients were included in the No-chemo group. We selected one month as the cut-off, as that is typically the period during which we avoid elective cancer surgery; this is due to concerns about immunosuppression and interference with wound healing. Both the type and number of chemotherapeutic agents were abstracted, as was concurrent use of corticosteroids in both the Chemo and No-chemo groups.

Additional demographic variables included age (years), gender, and cancer diagnosis (none, lymphoma/leukemia, aerodigestive/gynecologic/genitourinary, other). Laboratory variables included admission white blood cell count (K/uL) (WBC), admission absolute neutrophil count (K/uL) (ANC), neutropenia (ANC < 1.5 K/uL), and admission serum albumin concentration (g/dL). Variables related to the index episode of acute diverticulitis included anatomic location (rectosigmoid vs. other), complicated (phlegmon, abscess, perforation, obstruction, or fistula) vs. uncomplicated, initial NOM, failure of NOM, surgical intervention at any time during the index admission, type of operation (primary anastomosis vs. diversion), hospital length of stay (LOS) (days), postoperative complications, and mortality.

Non-operative management was defined as any trial of medical management in lieu of an immediate operation for diverticulitis. Although details of NOM varied, the approach generally involved antimicrobial therapy, intravenous hydration, bowel rest, and advancement to low-residue diet following resolution of inflammatory markers (i.e., fever, leukocytosis, abdominal tenderness). Failure of NOM was defined as an operation for diverticulitis, at any time during the index admission, in a patient for whom NOM was initially attempted. Patients who failed NOM underwent open exploration. None of the patients in this series received laparoscopic wash-out. Diverticulitis was graded with the Hinchey classification for the initial as well as the recurrent episode. Postoperative complications were abstracted according to a standardized institutional complication-reporting system [28]. (Table 1)

Table 1.

Chemotherapeutic Agents

| Chemotherapeutic Agent | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Doxorubicin | 22 (56.4) |

| Vinca alkaloids | 15 (38.5) |

| Taxol | 12 (30.8) |

| Cyclophosphamide | 10 (25.6) |

| Platinum | 10 (25.6) |

| 5-Flourouricil | 4 (10.3) |

| Gemcitabine | 4 (10.3) |

| Cytoxan | 4 (10.3) |

| Biologics | 4 (10.3) |

| Other | 5 (12.8) |

| Etoposide | 3 (7.7) |

Percentages do not sum to 100, as 36/39 patients (92.3%) had been exposed to multiple chemotherapeutic agents at the time of index hospitalization for diverticulitis.

Standardized chemotherapy records were searched to obtain both the intended and actual date of the next chemotherapy, so that any interruption and resumption of treatment could be determined. Medical records were also searched until 2010 for evidence of recurrence, interval resection, or stoma reversal (where applicable). Recurrent diverticulitis was defined and characterized using criteria identical to those of the index episode. Multiple (>1) recurrences were also noted. Complications following both the interval resection and surgery for recurrent diverticulitis were abstracted, as was the date of last follow-up, presence of a stoma at last follow-up, and date of mortality.

Statistical analyses were computed using SAS Version 9.1 (SAS Inc., Carey, NC) and SPSS version 17.0 (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL). Continuous data are expressed as median (range); categorical data are expressed as No. (%). Medians of continuous data were compared using the Wilcoxon Signed-Rank test. Proportions of categorical variables were compared using the Chi-squared test—unless expected cell counts were <5, in which case Fisher’s Exact Test was used. Kaplan-Meier curves were utilized to estimate overall survival and time to recurrence of diverticulitis. Time to recurrence was measured from the date of the index episode of diverticulitis to the time of first recurrence. The Log-rank test was used to compare the cumulative probability of overall mortality and recurrence between groups. Statistical significance was set at alpha=0.05.

RESULTS

A total of 131 patients met the inclusion criteria; 39 (29.8%) had received systemic chemotherapy a median of 8 days prior to admission (range 0–31 days). The chemotherapeutic agents used are summarized in Table 2. Baseline demographics and admission laboratory values were compared between the Chemo and No-chemo groups (Table 3). Age was similar between groups (p=0.21), although the Chemo group contained a higher proportion of male patients (64.1% vs. 42.4%, respectively, p=0.02). Patients in the Chemo group presented with significantly lower WBC (p<0.01) and ANC (<0.01) than those in the No-chemo group, and were more likely to be neutropenic (p<0.01). Admission serum albumin concentration did not differ between groups (p=0.13). Concurrent use of corticosteroids was significantly more common in the Chemo compared to the No-chemo group (p=0.03); corticosteroids were used either as component of treatment, or in the management of chemotherapy-related toxicity.

Table 2.

Group Demographics

| Chemo (n=39) | No Chemo (n=92) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years)* | 65.9 (35–81.2) | 66.3 (25–92) | 0.21 |

| Male* | 25 (64.1%) | 39 (42.4%) | 0.02 |

| Cancer** | <0.01 | ||

| None | 0 (0%) | 28 (30.4%) | |

| Lymphoma/Leukemia | 17 (43.6%) | 16 (17.4%) | |

| Aerodigestive/GU/GYN | 16 (41.0%) | 27 (29.4%) | |

| Other | 6 (15.4%) | 21 (22.8%) | |

| WBC (K/uL)* | 7.4 (0.3–30.9) | 11.7 (0.9–24.7) | <0.01 |

| ANC (K/uL)* | 4.5 (0.0–29.9) | 9.4 (0.1–20.0) | <0.01 |

| Neutropenia** | 10 (25.6%) | 2 (2.2%) | <0.01 |

| Albumin (g/dL)* | 3.7 (2.7–4.6) | 3.7 (2.2–4.8) | 0.13 |

| Corticosteroids** | 15 (38.5%) | 19 (20.7%) | 0.03 |

GU, genitourinary; GYN, gynecologic; WBC, white blood cell; ANC, absolute neutrophil count Neutropenia = ANC < 1.5K/µL.

Wilcoxon Signed-Rank test.

Chi-squared test—unless expected cell counts were <5, in which case Fisher’s Exact Test was used.

Table 3.

Index Episode of Diverticulitis

| Chemo (n=39) | No Chemo (n=92) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sigmoid** | 34 (87.2%) | 88 (95.7%) | 0.08 |

| Complicated** | 24 (61.5%) | 44 (47.8%) | 0.15 |

| Initial NOM** | 30 (76.9%) | 71 (77.2%) | 0.98 |

| Failure NOM** | 5 (13.2%) | 4 (4.4%) | 0.12 |

| Surgery** | 14 (35.9%) | 24 (26.1%) | 0.26 |

| Diversion** | 10 (71.4%) | 19 (79.2%) | 0.70 |

| ≥ 1 Postoperative complication** | 7 (50.0%) | 12 (50.0%) | 0.90 |

| LOS (days)* | 10.0 (2–44) | 8.5 (0–144) | 0.08 |

| Mortality** | 2 (5.1%) | 4 (4.4%) | 0.99 |

NOM, non-operative management; LOS, length of stay

Wilcoxon Signed-Rank test.

Chi-squared test—unless expected cell counts were <5, in which case Fisher’s Exact Test was used.

Data pertaining to the index episode of acute diverticulitis are summarized in Table 4. In both groups, the site of diverticulitis was predominantly the rectosigmoid. Chemo patients were not more likely to present with complicated diverticulitis than No-chemo patients (61.5% vs. 47.8%, respectively, p=0.15). There was no difference between the Chemo and No-chemo groups in the proportion of patients selected for initial NOM (76.9% vs. 77.2%, respectively, p=0.98). Failure of NOM was uncommon, and did not differ between the Chemo and No-chemo groups (13.2% vs. 4.4%, respectively, p=0.12). Among patients undergoing surgery during the index admission, the proportion of those who were diverted did not differ between the Chemo and No-chemo groups (71.4% vs. 79.2%, respectively, p=0.70). The incidence of any postoperative complication did not differ between the Chemo and No-chemo groups (50.0% for each group, p=0.90). Neither hospital LOS (p=0.08) nor mortality (p=0.99) differed between groups.

Table 4.

Episode of Recurrent Diverticulitis

| Chemo (n=8) | No Chemo (n=17) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Complicated** | 7 (87.5%) | 5 (29.4%) | 0.01 |

| Initial NOM** | 4 (50.0%) | 15 (88.1%) | 0.06 |

| Failure NOM** | 2 (50.0%) | 2 (13.3%) | 0.18 |

| Surgery** | 6 (75.0%) | 4 (23.5%) | 0.03 |

| Diversion** | 6 (100.0%) | 1 (25.0%) | 0.03 |

| ≥ 1 Postoperative complication** | 4 (66.7%) | 2 (50.0%) | 0.99 |

| LOS (days)* | 17 (9–60) | 6 (0–40) | 0.01 |

| Mortality** | 1 (12.5%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0.32 |

NOM, non-operative management; LOS, length of stay

Wilcoxon Signed-Rank test.

Chi-squared test—unless expected cell counts were <5, in which case Fisher’s Exact Test was used.

Admission for diverticulitis resulted in interruption of chemotherapy in 32 of 39 patients (82.1%). Of these 32 patients, 28 (87.5%) eventually resumed chemotherapy a median of 2.1 months later (range 0.8–40.4). The remainder (n=4, 12.5%) did not resume chemotherapy due to death from cancer progression.

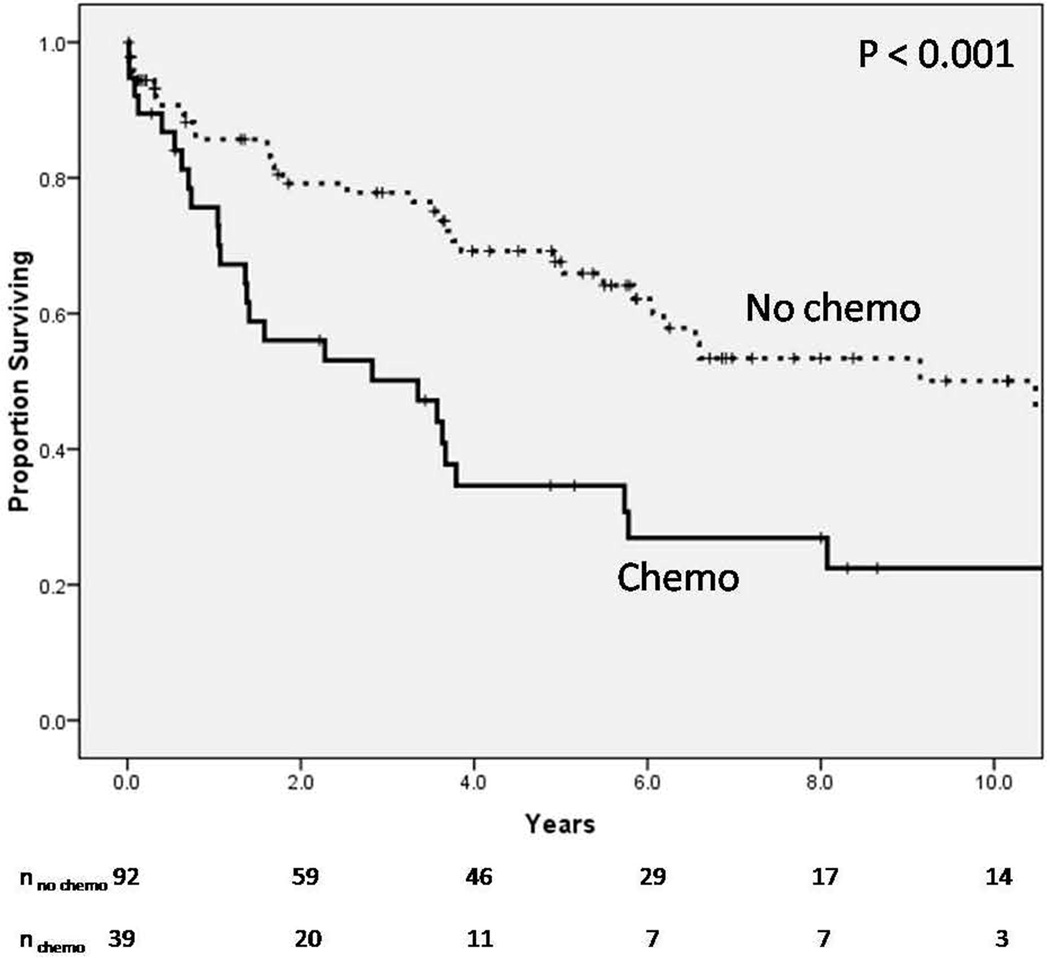

Median follow-up for the sample was 44 months (range 0–241 months). Overall mortality was significantly higher for the Chemo compared to the No-chemo group (Figure 1). Median survival for the Chemo group was 3.4 years; median survival for the No-chemo group had not been reached at 10 years. Patients in the No-chemo group did not have cancer, had low risk cancers, or had cancers that were previously resected without need for systemic chemotherapy; hence, not all patients in the No-chemo group had undergone chemotherapy. Among patients who did not undergo surgery during the index hospitalization (n=93), the likelihood of interval resection did not differ between the Chemo and No-chemo groups (24.0% vs. 16.2%, respectively, p=0.39). However, the morbidity of an interval resection was significantly higher in the Chemo compared to the No-chemo group. All patients in the Chemo group had at least one postoperative complication following interval resection (n=6/6, 100%); only 1 patient in the No-chemo group had a complication (n=1/11, 9.1%, p < 0.01).

Figure 1.

Overall mortality

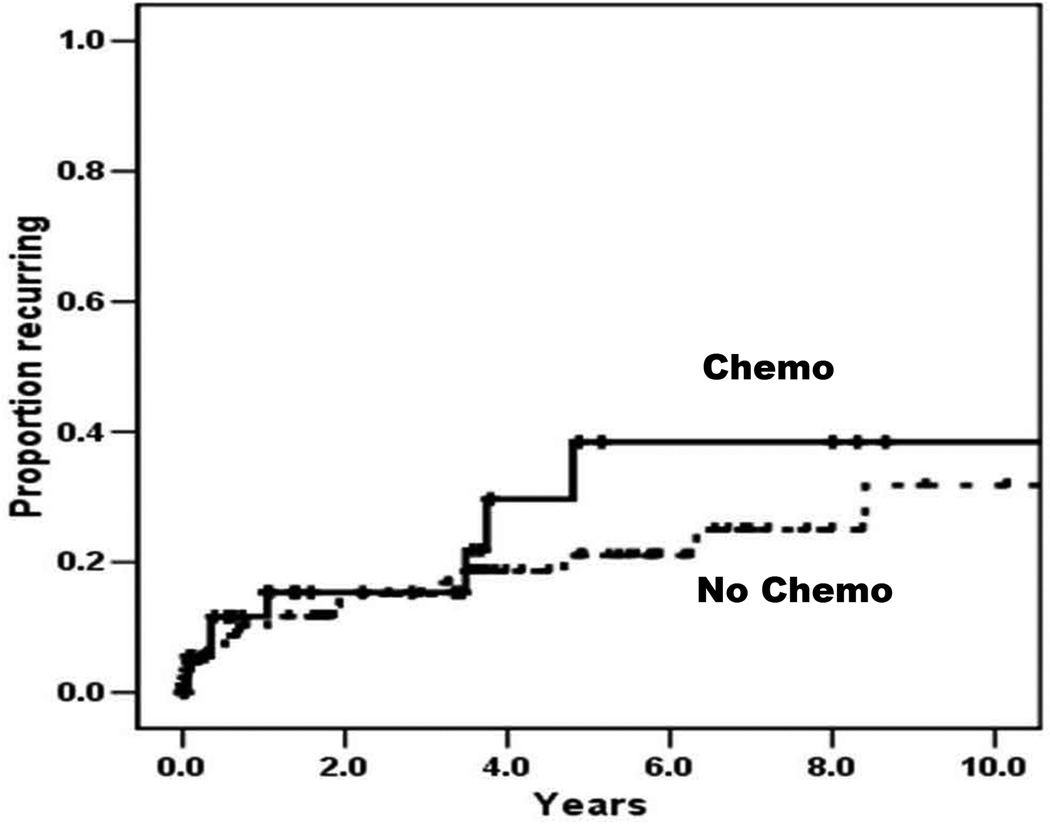

A total of 25 patients (19.0%) developed recurrent diverticulitis: 8 in the Chemo group (20.5%) and 17 in the No-chemo group (18.5%). The cumulative likelihood of recurrence did not differ between groups (Figure 2). Outcomes of the episode of recurrent diverticulitis are shown in Table 4. The likelihood of recurrence of complicated diverticulitis was significantly increased in the Chemo group compared to the No-chemo group (87.5% vs. 29.4%, respectively, p=0.01). A trend towards decreased likelihood of NOM for recurrent diverticulitis was observed for the Chemo group compared to the No-chemo group, although this did not reach statistical significance (50.0% vs. 88.1%, respectively, p=0.06). There was no significant difference in the likelihood of failure of NOM between groups, although this was a rare event (n=2 for each group). However, Chemo patients were significantly more likely than No-chemo patients to require emergent surgery during hospitalization for recurrent diverticulitis (75.0% vs. 23.5%, respectively, p=0.03), and were more likely to be diverted (100.0% vs. 25.0%, respectively, p=0.03). Differences in perioperative morbidity (p=0.99) and mortality (p=0.32) did not reach statistical significance.

Figure 2.

Recurrent diverticulitis

Specific postoperative complications following emergent surgery for the initial episode of diverticulitis, elective interval resection, and emergent surgery for recurrent diverticulitis, are summarized in Table 5. Multiple recurrences were rare (n=8/131, 6.1%), and were not more common in the Chemo compared to the No-chemo group (3.1% vs. 7.6%, p=0.43). Chemo patients were not more likely to have a stoma at last follow-up (28.2% vs. 15.2%, respectively, p=0.08).

Table 5.

Postoperative complications

| Initial Episode | Interval Resection | First Recurrence | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chemo | No Chemo | Chemo | No Chemo | Chemo | No Chemo | |

| Patients undergoing surgery | 14 | 24 | 6 | 11 | 6 | 4 |

| Patients with ≥ 1 complication | 7 | 12 | 6 | 1 | 4 | 2 |

| Surgical site infection | 2 | 3 | - | - | 2 | - |

| Intra-abdominal abscess | 2 | 4 | - | - | 1 | 1 |

| Pneumonia | 1 | 2 | 2 | - | 2 | - |

| Urinary tract infection | - | - | 1 | - | 1 | 2 |

| Sepsis | 2 | 2 | - | - | 1 | - |

| Wound dehiscence | 1 | - | - | - | - | - |

| Ileus | - | 1 | 1 | 1 | - | - |

| Venous thromboembolism | - | 1 | 1 | - | 1 | - |

| Colovesical fistula | - | 1 | - | - | - | - |

| Intra-abdominal hemorrhage | - | - | 1 | - | - | - |

| Gastrointestinal hemorrhage | - | 1 | 1 | - | - | - |

| Atrial fibrillation | - | 1 | 2 | - | 1 | - |

Total complications do not sum to the total number of patients with ≥ 1 complication, as some patients had more than one complication.

DISCUSSION

The guidelines put forth in 2014 by the American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons (ASCRS) recommend that surgeons maintain a low threshold when considering operative intervention as definitive treatment, during the first hospitalization for acute diverticulitis, in immunosuppressed patients with chronic renal failure or collagen vascular disease. That is because these patients are at greater risk of recurrent complicated diverticulitis, requiring emergency surgery. Furthermore, most authors recommend interval resection following a single episode of diverticulitis in IMS patients Despite these recommendations, there is no data comparing initial and long-term outcomes of acute diverticulitis in cancer patients who are on chemotherapy to patients who are not [4, 21, 22]. In this study, the Chemo group did not differ significantly from the No-chemo group in terms of severity of index episode of acute diverticulitis, time to resumption of chemotherapy, failure of NOM, and frequency of recurrence. Chemo patients recurred with more severe disease, were more likely to undergo emergent surgery, and were more likely to be diverted; however, perioperative morbidity and mortality were not increased relative to No-chemo patients. By contrast, Chemo patients were significantly more likely to incur a postoperative complication following interval resection. These data argue against routine surgical intervention in Chemo patients with diverticulitis, in both the acute and interval settings.

Prior data addressing outcomes in IMS patients with diverticulitis are sparse. Perkins et al. reviewed 86 patients admitted with diverticulitis from 1980–1983; 10 patients were immunocompromised, 3 of whom had recently received chemotherapy [19]. All of the IMS patients failed NOM, compared with only 24% of the immunocompetent patients. Both morbidity and mortality were increased in the IMS group, although statistical significance was not reported. Tyau et al. reported on 209 patients with diverticulitis treated at a single institution from 1984–1989 [20]. Forty patients (19%) were immunocompromised, 6 of who had recently undergone chemotherapy. Again, a higher likelihood of failure of NOM was observed in the IMS compared to the Non-IMS group (58% vs. 32%, respectively, p<0.05), as were higher rates of postoperative morbidity (65% vs. 23.6%, p<0.05) and mortality (39.1% vs. 1.8%). Chapman et al. described a similar association between IMS and morbidity and mortality from complicated diverticulitis [17].

The results of our study differ from these reports in several ways. In the current series, NOM was attempted in a majority of cases and rarely failed, regardless of exposure to chemotherapy. Furthermore, postoperative morbidity and mortality were lower in the Chemo group than has been reported in previous studies. These disparities may reflect either a general improvement in NOM of patients with diverticulitis over time, or a healthier cohort of Chemo patients. The overall incidence of recurrent diverticulitis in our series (19.5%) was also lower than in many previous studies [11, 13, 14].. Finally, the relatively low incidence of interval resection in the Chemo group (24.0%), suggests a disparity between existing recommendations and current practice.

Our findings indicate that the increased severity of recurrent disease does not justify mandatory interval resection following a single episode of diverticulitis. However, while these data may be used to inform decision-making, clinical judgment remains paramount in managing the individual patient with diverticular disease. Our study is limited by the possibility of a Type II error, secondary to small sample size. In particular, a larger sample may have revealed significant differences in the likelihood of either complicated diverticulitis or failure of NOM between the Chemo and No-chemo groups for the index admission. In both groups, however, failure of NOM was rare. An additional limitation common to retrospective studies involves confounding; the Chemo and No-chemo groups likely differed systematically in ways other than exposure to chemotherapy. For example, approximately one-third of patients in the No-chemo group had no history of malignancy. The significantly higher overall mortality observed in the Chemo group underscores the possibility of such confounding. However, this observation should be incorporated into the management of chemotherapy patients with diverticulitis, and should inform any decision to proceed with interval resection. Another difference involved the greater likelihood of corticosteroid use in the Chemo group versus the No-chemo group. Although corticosteroid use may have exerted an independent immunosuppressive effect, many of the patients in the Chemo group received only a single dose of steroids during chemotherapy, for anti-emetic purposes. Unfortunately, the small overall sample size precluded subgroup analysis of patients who did not receive steroids. However, the equivalent severity of disease observed in the Chemo and No-chemo groups during the index admission argues against a substantial degree of confounding by steroid use.

Caution should be exercised in extrapolating our results to other groups of IMS patients (e.g., transplant patients). Biondo et al concluded that IMS patients with diverticulitis who were treated successfully by medical management need not be advised to undergo elective sigmoidectomy more often than Non-IMS patients (16). We arrived at the same conclusion, based on our experience with a cancer patient population.

Use of recent exposure to chemotherapy as the primary predictive variable likely captured a relatively broad range of IMS patients. It is possible that additional refining of the sample (e.g., to patients who had either received chemotherapy within a shorter interval prior to presentation, or had documented neutropenia at presentation), may have increased the ability to detect a deleterious effect of chemotherapy. However, such a limitation would preclude a meaningful statistical analysis. Finally, our comparator group consisted predominantly of patients with malignancy--a comorbidity that may cause immunosuppression independent of chemotherapy. It is possible that chemotherapy patients with diverticulitis may fare worse compared to the general population. However, this particular control group was chosen in order to minimize additional confounding.

CONCLUSIONS

Our report comprises the largest series of chemotherapy patients hospitalized for acute diverticulitis. In comparison to patients not exposed to chemotherapy, chemotherapy patients did not present with more severe disease and were not more likely to fail NOM during the index hospitalization. Chemotherapy was resumed in a majority of patients following the episode of diverticulitis. Interval resection was associated with a significantly increased morbidity in chemotherapy patients. Finally, the likelihood of recurrence was not increased in the Chemo group, although recurrent disease was more severe in these patients. These data do not support application of the current recommendations—for routine elective surgical management of IMS patients with acute diverticulitis, including interval resection following a single episode—to those receiving chemotherapy. NOM, whether in the acute or interval setting, appears preferable in this population whenever possible. In practice, care must be individualized regardless of exposure to chemotherapy. Continued research is needed in order to refine an evidence-based approach to the management of IMS patients with diverticular disease.

HIGHLIGHTS.

Immunosuppressed patients have traditionally been regarded as having increased risk of both complicated and recurrent diverticulitis. A number of series have reported a high likelihood of failure in non-operative management of immunosuppressed patients, as well as increased morbidity and mortality from acute diverticulitis. As a result, several authors have argued for interval resection following an initial episode of diverticulitis in immunosuppressed patients.

This is one of the largest studies to focus on cancer patients with acute diverticulitis.

In this study, we found that the severity of diverticulitis and disease progression was not affected by administration of chemotherapy. Hence, chemotherapy can be safely resumed in patients with acute diverticulitis, once the acute inflammation subsides.

We also found that the incidence of recurrent diverticulitis was the same in cancer patients who were actively receiving chemotherapy, compared to those who were not.

Despite current recommendations, our study does not support routine elective interval resection after a single episode of diverticulitis in cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy.

Complications.

| Grade of complication | Management and Result |

|---|---|

| 1 | Reguiring oral medication |

| 2 | Requiring intravenous treatment |

| 3 | Requiring surgical or image-guided intervention |

| 4 | Resulting in permanent disability |

| 5 | Death |

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

Funding support: This study was funded in part by the Cancer Center Core Grant P30 CA008748. The Core Grant provides funding to institutional cores, such as Biostatistics and Pathology, which were used in this study.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Blachut K, Paradowski L, Garcarek J. Prevalence and distribution of the colonic diverticulosis. Review of 417 cases from Lower Silesia in Poland. Rom J Gastroenterol. 2004;13(4):281–285. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Loffeld RJ, Van Der Putten AB. Diverticular disease of the colon and concomitant abnormalities in patients undergoing endoscopic evaluation of the large bowel. Colorectal Dis. 2002;4(3):189–192. doi: 10.1046/j.1463-1318.2002.00328.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Paspatis GA, Papanikolaou N, Zois E, Michalodimitrakis E. Prevalence of polyps and diverticulosis of the large bowel in the Cretan population. An autopsy study. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2001;16(4):257–261. doi: 10.1007/s003840100304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rafferty J, Shellito P, Hyman NH, Buie WD Standards Committee of American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons. Practice parameters for sigmoid diverticulitis. Dis Colon Rectum. 2006;49(7):939–944. doi: 10.1007/s10350-006-0578-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gaertner WB, Kwaan M, Madoff RD, et al. The evolving role of laparoscopy in colonic diverticular disease: a systematic review. World J Surg. 2013;37(3):629–638. doi: 10.1007/s00268-012-1872-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tursi A. Advances in the management of colonic diverticulitis. CMAJ. 2012;184(13):1470–1476. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.120580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Janes S, Meagher A, Frizelle FA. Elective surgery after acute diverticulitis. Br J Surg. 2005;92(2):133–142. doi: 10.1002/bjs.4873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Parks TG. Natural history of diverticular disease of the colon. A review of 521 cases. Br Med J. 1969;4(5684):639–642. doi: 10.1136/bmj.4.5684.639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pieracci FM, Barie PS. Management of severe sepsis of abdominal origin. Scand J Surg. 2007;96(3):184–196. doi: 10.1177/145749690709600302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Morris CR, Harvey IM, Stebbings WS, Hart AR. Incidence of perforated diverticulitis and risk factors for death in a UK population. Br J Surg. 2008;95(7):876–881. doi: 10.1002/bjs.6226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Boles RS, Jr, Jordan SM. The clinical significance of diverticulosis. Gastroenterology. 1958;35(6):579–582. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Broderick-Villa G, Burchette RJ, Collins JC, Abbas MA, Haigh PI. Hospitalization for acute diverticulitis does not mandate routine elective colectomy. Arch Surg. 2005;140(6):576–581. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.140.6.576. discussion 581-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chappuis CW, Cohn I., Jr Acute colonic diverticulitis. Surg Clin North Am. 1988;68(2):301–313. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6109(16)44479-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Anaya D, Flum D. Assessing the risk of emergency colectomy and colostomy in patients with diverticular disease; Presented at the American College of Surgeons 90th Annual Clinical Congress; October 2004; New Orleans, LA. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tursi A, Elisei W, Giorgetti GM, Inchingolo CD, Nenna R, Picchio M, Brandimarte G. Detection of endoscopic and histologic inflammation after an attack of colonic diverticulitis is associated with higher diverticulitis recurrence. J Gastrointestin Liver Dis. 2013;22(1):13–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Biondo S, Borao JL, Kreisler E, et al. Recurrence and virulence of colonic diverticulitis in immunocompromised patients. Am J Surg. 2012;204(2):172–179. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2011.09.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chapman J, Davies M, Wolff B, et al. Complicated diverticulitis: is it time to rethink the rules? Ann Surg. 2005;242(4):576–581. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000184843.89836.35. discussion 581-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Salem L, Veenstra DL, Sullivan SD, Flum DR. The timing of elective colectomy in diverticulitis: a decision analysis. J Am Coll Surg. 2004;199(6):904–912. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2004.07.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Perkins JD, Shield CF, 3rd, Chang FC, Farha GJ. Acute diverticulitis. Comparison of treatment in immunocompromised and nonimmunocompromised patients. Am J Surg. 1984;148(6):745–748. doi: 10.1016/0002-9610(84)90429-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tyau ES, Prystowsky JB, Joehl RJ, Nahrwold DL. Acute diverticulitis. A complicated problem in the immunocompromised patient. Arch Surg. 1991;126(7):855–858. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1991.01410310065009. discussion 858-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Farthmann EH, Ruckauer KD, Haring RU. Evidence-based surgery: diverticulitis--a surgical disease? Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2000;385(2):143–151. doi: 10.1007/s004230050257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Feingold D, Steele SR, Lee S, et al. Practice parameters for the treatment of sigmoid diverticulitis--supporting documentation. The Standards Task Force. The American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons. Dis Colon Rectum. 2014;57:284–294. doi: 10.1097/DCR.0000000000000075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Martin ST, Stocchi L. New and emerging treatments for the prevention of recurrent diverticulitis. Clin Exp Gastroenterol. 2011;4:203–212. doi: 10.2147/CEG.S15373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sachar D National Diverticulitis Study Group. Diverticulitis in immunosuppressed patients. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2008;42(10):1154–1155. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0b013e3181862ac1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Steele TA. Chemotherapy-induced immunosuppression and reconstitution of immune function. Leuk Res. 2002;26(4):411–414. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2126(01)00138-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rasmussen L, Arvin A. Chemotherapy-induced immunosuppression. Environ Health Perspect. 1982;43:21–25. doi: 10.1289/ehp.824321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gutierrez MG, Kirkpatrick CH. Recognition of the immunocompromised patient. Chest Surg Clin N Am. 1999;9(1):1–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Grobmyer SR, Pieracci FM, Allen PJ, Brennan MF, Jaques DP. Defining morbidity after pancreaticoduodenectomy: use of a prospective complication grading system. J Am Coll Surg. 2007;204(3):356–364. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2006.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]