Abstract

Comparative developmental studies of the mammalian brain can identify key changes that can generate the diverse structures and functions of brains. We have studied how the neocortex of early mammals became organized into functionally distinct areas, and how the current level of cortical cellular and laminar specialization arose from the simpler premammalian cortex. We demonstrate the neocortical organization in early mammals that is most informative for an understanding of how the large, complex human brain evolved from a long line of ancestors. The radial and tangential enlargement of the cortex was driven by changes in the patterns of cortical neurogenesis, including alterations in the proportions of distinct progenitor types. Some cortical cell populations travel to the cortex through tangential migration, others migrate radially. A number of recent studies have begun to characterize the chick, mouse, human and non-human primate cortical transcriptome to help us understand how gene expression relates to the development, and to the anatomical and functional organization of the adult neocortex. Although all mammalian forms share the basic layout of cortical areas, the areal proportions and distributions are driven by distinct evolutionary pressures acting on sensory and motor experiences during the individual ontogenies.

Keywords: cortical neurogenesis, intermediate progenitors, tangential neuronal migration, comparative transcriptomics, cortical arealisation, subterranean vision

General overview

Understanding how the mammalian isocortex (neocortex) evolved to its present complex state is a fascinating topic for neuroscience, genetics, bioinformatics and comparative biology. It is a fundamental question to identify the developmental processes that evolved to generate a six-layered neocortex rather than an earlier cortex more like the dorsal cortex of reptiles, with a single layer of pyramidal cells, a scattering of intrinsic inhibitory neurons, and only a few functional divisions. To gain insights into these developmental patterns we have studied the development and adult organization of various extant mammalian species to correlate cortical cell numbers and neuronal cell types with the cortical progenitor populations, with the elaboration of radial and tangential developmental migratory paths, and with their modes of proliferation in different species. We consider the issues under 5 headings.

(1) The organization in early mammals of the neocortex into functionally distinct areas and the level of cellular and laminar specialization in this neocortex will be reviewed. The cortical specializations that occurred as early mammals diverged, and modern mammals emerged will be considered. (2) Several sectors of the telencephalic germinal zones contribute to the cells of the cerebral cortex and many of these cells arrive via tangential migratory pathways. Conserved and changing patterns of early tangential migrations in the telencephalon will be reviewed with a focus on the cells migrating into the olfactory bulb and cerebral cortex. (3) Various progenitors contribute to the formation of cortical layers and cell types through specific lineages. These include ventricular or apical radial glia, subventricular (or basal) intermediate progenitors and subventricular (outer) radial glial cell types). The key questions here relate to the regulation of brain size and folding. (4) An increasing knowledge of neuronal numbers, cell types and their molecular taxonomy is currently redefining our view of cortical anatomy. The characterization of chick, mouse, human and non-human primate cortical transcriptomes shows how gene expression relates to the development and functional organization of the neocortex. (5) Comparative studies on species with limited visual input provide valuable models to study the contribution of sensory inputs to cortical specialization. Understanding the evolutionary effects of sensory deprivation on cortical development is fundamental for revealing genetic and environmental factors that allocate cortical territories for the various sensory and motor representations during normal development and in pathological conditions.

(1) Reconstructing the evolution of neocortex from the first mammals to humans

Mammals represent the only surviving branch of the synapsid clade radiation of stem amniotes that also gave rise to the sauropsid clade with surviving reptiles and birds. All surviving mammals are believed to have evolved from a single common ancestor that produced six major branches of mammalian evolution (Murphy et al., 2004), and an estimated 56 thousand different species. All mammals that have been studied are characterized by a dorsal cap of neocortex in the forebrain that differs from its homologue, the dorsal cortex, in reptiles by having six cortical layers and a number of structurally and functionally specialized subdivisions, the cortical areas. A major question is how this six-layered neocortex emerged from an earlier cortex that probably resembled the dorsal cortex of reptiles, with a single layer of pyramidal cells, a scattering of intrinsic inhibitory neurons, and few functional divisions (Molnár, 2011).

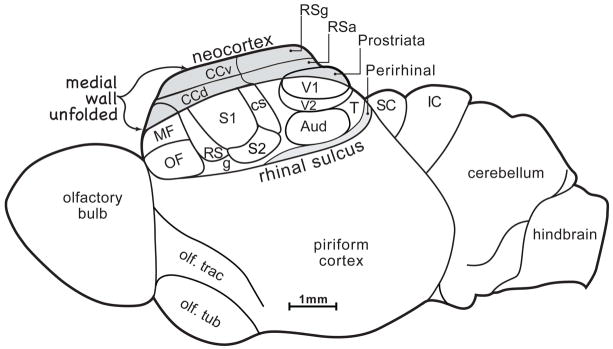

The fossil record is never as complete and informative as we would hope, but enough evidence has accumulated from well-preserved skulls to indicate that most early mammals were small and had small brains with little neocortex (Fig. 1). The olfactory piriform cortex and olfactory bulbs were relatively large, dominating the surface of the forebrain, and clearly indicating that the processing of olfactory information was paramount, and that neocortex had a limited role in guiding behavior. It is difficult to deduce how this small, thin cap of neocortex was organized, but powerful inferences can be made from the results of the many studies of cortical organization in the brains of currently living species. Studies of cortical organization and structure have been most informative when conducted on small-brained mammals with little neocortex, across the six major branches of the mammalian radiation, because this cortex has fewer subdivisions, and shared features are not as likely to be hidden in a maze of more recently derived cortical areas. Features such as cortical areas shared across members of all six major branches of the mammalian radiation are those most likely to be retained from a common ancestor (Figure 1).

Figure 1. The proposed organization of neocortex in early mammals.

The proportion of the forebrain devoted to the neocortex of early mammals was small compared to that in most subsequent mammals, and there were few cortical areas. Neocortex included orbital frontal (OF) and medial frontal (MF) areas, primary somatosensory cortex (S1) bordered by secondary, dorsal, and caudal somatosensory areas (S2, RS, CS), possibly a gustatory area (g), and primary, secondary, and temporal visual areas (V1, V2, T), auditory cortex of one or more divisions (Aud), ventral and dorsal cingulate areas (CCv, CCd), and retrosplenial granular and agranular areas (RSg, RSa) as well as an area prostriata, a visual area. The superior colliculus (SC) and inferior colliculus (IC) of the midbrain were not covered by neocortex or cerebellum, and the olfactory bulb and piriform cortex were proportionately large.

Early primates were characterized by an increase in the number of visual areas, and an expansion of occipital and temporal visual cortex, as well as an expansion of posterior parietal sensorimotor areas that further connected visual and somatosensory to motor and premotor cortex. Overall, neocortex was enlarged, and neuronal packing density in cortex was increased, especially in primary visual cortex (Herculano-Houzel et al., 2007, Collins et al., 2010), and structural differences between some of the cortical areas became more pronounced (e.g., Wong et al., 2010). The smallest of extant anthropoid primates, the marmosets, have brains in the 300–400 gram range that contain well under 1 billion neurons, while the massive human brain of 1500 grams has over 85 billion neurons (Herculano-Houzel et al., 2007; Azevedo et al., 2009). Much more needs to be known about how brains and functional parts of brains vary in neuron numbers.

The neocortex of some anthropoid primates became extremely large, especially in humans where the massive brain is 80% neocortex. The extensive sheet of neocortex is divided into an estimated 200 areas in each human hemisphere, and some regions and areas are specialized in different ways in each hemisphere, adding to the complexity to the cortex and behavioral capabilities (Kaas, 2013).

(2) Dynamics of the movements of cell populations during telencephalic development in mammals

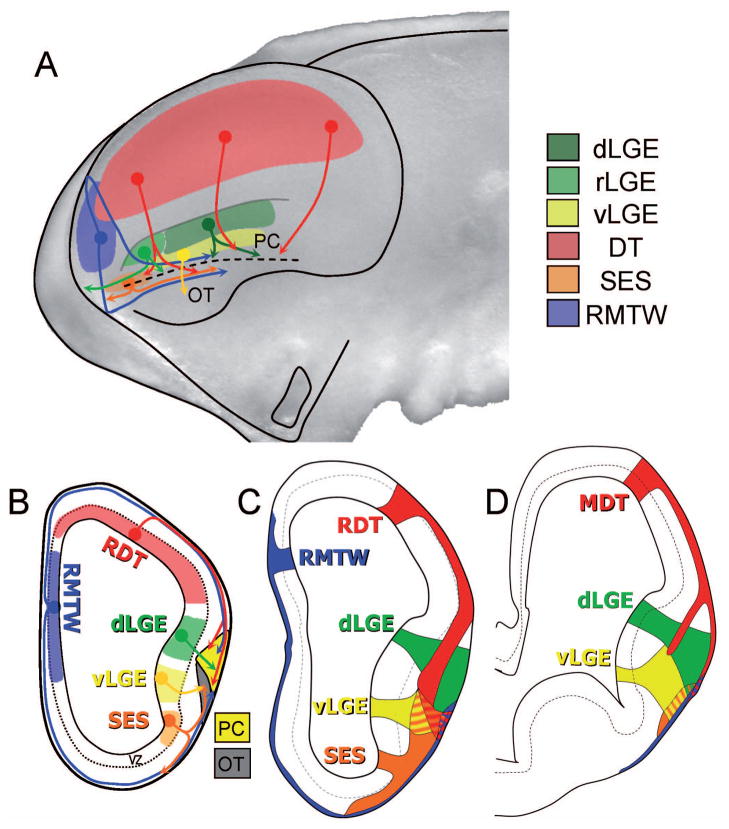

The cortical neuroepithelium is a pseudo-stratified columnar epithelium containing densely packed cells. The germinative area is at the ventricular surface of the telencephalon. Neurons are generated here in the ventricular zone in successive waves during the developmental period. Generated cells move away from their site of neurogenesis to reach a specific destination closer to the pial surface of the same or of a different cortical area. Two distinct mechanisms allow newborn neurons to reach their final destinations, radial or tangential migration. In the radial migrations, the nuclei of cortical newborn cells move from their place of origin in the ventricular zone toward the pial surface, following an inside-out sequence (Angevine and Sidman, 1961). They can stop at different levels of their trail to colonize different strata, in accord with their birthdates, initiating the layered structure of the cerebral cortex. It was Rakic who revealed that newborn cells attach to the radial glia and use them as a scaffold to migrate to the final cortical laminar destination (Rakic, 1972). The neurogenetic nature of radial glial cells was directly demonstrated (Noctor et al., 2001; Tamamaki et al., 2001). However, it has now been shown that not all daughter cells remain near to the overlying cerebral area where they are generated (Walsh and Cepko, 1993). In fact, there is a non-gliophilic tangential migratory mechanism that allows cells to move for long distances and colonize other brain regions, sometimes very far from their site of origin (Figure 2).

Figure 2. The sites of generation of cortical nerve cells, as well as their migratory routes are summarized here for tangentially migrating cell populations that contribute to the development of various telencephalic structures.

The olfactory cortex is the first structure developed in the telencephalon (from E11 in mouse). This occupies the ventro-lateral part of the hemisphere and consists of several structures: the piriform cortex (PC), olfactory tubercle (OT) and entorhinal cortex (EC). Each of these areas is formed by the migration of several cell populations generated in different telencephalic sites.

The vast majority of cells that project from the cortex (pyramidal neurons) are generated in the germinative area of the cortical neuroepithelium of the dorsal telencephalon (DT), and the cortical interneurons are generated in the basal telencephalon, specifically in the three subdivisions of the ganglionic eminences (lateral, medial and caudal)(dLGE – dorsal lateral ganglionic eminence; vLGE – ventral lateral ganglionic eminence; rLGE - rostral portion of lateral ganglionic eminence).

The olfactory cortex is the first structure developed in the telencephalon (from E11 in the mouse). It occupies the ventro-lateral part of the telencephalon and consists of several structures: the piriform cortex (PC), olfactory tubercle (OT) and entorhinal cortex (EC). SES indicates the region of the septo-eminential sulcus.

More or less at the same time, the development of the cerebral cortex starts in the following sequence:

Cajal-Retzius (C-R) cells are mainly generated between E10.5 and E11.5 in a caudo-medial extracortical structure called the cortical hem and they migrate tangentially, subpially and obliquely (from caudal/medial to rostral/lateral areas).

Subplate (SP) cells are co-generated at the same timeas C-R cells and, in the beginning, they occupy the same cortical stratum in the preplate. Recent work showed that a considerable proportion of the subplate neurons originates from the rostral and medial telencephalic wall (RMTW)(Pedraza et al., 2013).

The vast majority of cells projecting axons from the cortex (pyramidal neurons) are generated in the germinative area of the cortical neuroepithelium of the dorsal telencephalon and the cortical interneurons are generated in the basal telencephalon, specifically in the three subdivisions of the ganglionic eminences (lateral, medial and caudal).

Tangential migratory mechanisms contribute to olfactory and cerebral cortical development

De Carlos and colleagues have described that some cells generated in the subpallial ganglionic eminences migrate toward the cortical neuroepithelium, cross the cortico-striate boundary and move long distances coursing tangentially into the preplate/marginal zone of the neocortical primordium (De Carlos et al., 1996). Subsequently, this finding was confirmed and extended by new data showing that these tangentially migrating cells were GABAergic (Anderson et al., 1997; Tamamaki et al., 1997).

The olfactory cortex is the first region to differentiate in the telencephalon (from E11 mouse). It occupies the ventro-lateral part of the telencephalon and includes of several structures: the piriform cortex (PC), olfactory tubercle (OT) and entorhinal cortex (EC)(Figure 2A,B). The olfactory cortex is formed as a consequence of the convergence of numerous cell populations each of which is generated in a different area of the medial telencephalon (García-Moreno et al., 2007; Pedraza and De Carlos, 2012; Ceci et al., 2012).

The neocortex is the largest structure formed in the telencephalon by the same convergence of diverse cell populations each of which is generated in different proliferative areas throughout the telencephalon. These populations are: Cajal-Retzius cells, subplate cells, interneurons and projection neurons. Cajal-Retzius (C-R) cells are mainly generated between E10.5 and E11.5 in the mouse. They are generated in an extracortical structure that is situated in the medial and caudal part of the telencephalon, called the cortical hem. The cells then migrate tangentially, subpially and obliquely through the cortical preplate from caudal/medial to rostral/lateral areas to cover the entire cerebral cortex within 24 hours (García-Moreno et al., 2007; Ceci et al., 2010; Miquelajáuregui et al., 2010).

Subplate (SP) cells are generated concurrently with the C-R cells and in the beginning, occupy the same cortical strata, the preplate. It is considered that this cell type is generated in the cortical ventricular zone, but it has been recently described that an important part of this heterogeneous population are generated in an extracortical area in the rostal medial telencephalic wall (RMTW) and reach the cortex by tangential migration (Pedraza and De Carlos, 2012; Pedraza et al., 2013; Figure 2B,C). The first cells to send axons out of the cortical neuroepithelium are a subpopulation of the SP cells (Marín-Padilla, 1971; McConnell et al., 1989; De Carlos and O’Leary, 1992); however, the main and most important projecting cells of the cortex are the large, medium and small pyramidal cells. It is accepted that these cells are generated in the germinative area (VZ/SVZ) of the neocortical neuroepithelium and migrate along the radial glia to settle in their particular laminae, contributing to the layering the cortex. Cortical interneurons are generated in the subpallial ganglionic eminences, specifically in each of the three subdivisions of the ganglionic eminence (lateral, medial and caudal, see Figure 2 for summary) and enter the neuroepithelium by tangential migration (De Carlos et al., 1996; Anderson et al., 1997; Tamamaki et al., 1997).

Comparative developmental studies of avian and reptilian brains have shown that dorsal telencephalic structures are formed by several cell populations that are generated in distinct areas (Cobos et al., 2001; Tourto et al., 2003; Métin et al., 2007). The extent to which this process is contributing to human cortical development is currently subject of debate (Clowry et al., 2010; Hansen et al., 2011; Molnár and Butt, 2013).

Recent comparisons of the proportions of the several cortical progenitors in selected species during embryonic neurogenesis have revealed the elaboration and cytoarchitectonic compartmentalization of the germinal zone, with alterations in the proportions of various progenitor types (Cheung et al., 2010; Martinez-Cerdeño, 2006; Hevner and Haydar, 2012).

(3) Molecular and Cellular Characteristics of Cerebral Cortical Intermediate Progenitors

Progenitor cells that divide at a distance from the ventricular surface were recognized in many classic studies (reviewed by Hevner, 2006), but the significance of non-surface mitoses remained uncertain until 2004. A trio of time-lapse imaging studies (Haubensak et al., 2004; Miyata et al., 2004; Noctor et al., 2004) showed that the basal or abventricular (“non ventricular surface” or “non-apical”) divisions in embryonic rodent neocortex are neurogenic (not gliogenic), and produce glutamatergic (not GABAergic) neurons. Those studies also showed that IPs are derived from radial glia (RG) progenitors, proliferate for only one or two mitotic cycles before differentiating into postmitotic neuroblasts, and extend and retract processes suggesting possible stages of IP migration. Since then, our views of IP roles in cortical neurogenesis have evolved. Here we focus on: (1) molecular profiles of IPs, (2) apical and basal types of IPs, (3) Delta-Notch signaling by IPs, and (4) IP contributions to cortical layers.

Molecular profiles of IPs

While IPs were first distinguished by their cellular properties, molecular analyses have yielded many key insights. IPs express unique transcriptomic profiles, including expression of transcription factor Tbr2 (also known as Eomes) in all cortical IPs (Englund et al., 2005; Kawaguchi et al., 2008; Ayoub et al., 2011; Cameron et al., 2012). Dozens of IP-enriched genes have been identified: examples include Neurog2, Hes6, and Rasgef1b (Kawaguchi et al., 2008; Ayoub et al., 2011). Nevertheless, IPs are far from homogeneous. Molecular profiling distinguished two types of IPs (Kawaguchi et al., 2008), and revealed temporal and spatial diversity as different cortical layers and areas are generated (Elsen et al., 2013). Expression of genes such as Svet1 and Cux2 suggested that IPs contribute to upper cortical layers (Tarabykin et al., 2001; Zimmer et al., 2004), although not exclusively. Expression of Scrt2 suggested that IPs move from VZ to SVZ by a type of epithelial-mesenchymal transition (Itoh et al., 2013). Molecular analyses implicated IPs in Delta-Notch signaling (Kawaguchi et al., 2008; Nelson et al., 2013). Molecular comparisons are also telling us about the evolution of IPs (Lui et al., 2011; Molnár and Clowry, 2012).

Apical and basal types of intermediate progenitors (IPs)

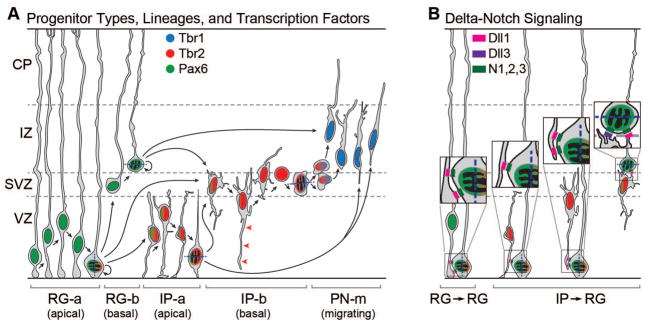

Unbiased microarray profiling of >100 single cells isolated from the VZ and SVZ of E14.5 mice distinguished four types of cells: RG, new postmitotic neurons, and two types of IPs. The latter, now known as apical and basal IPs (Hevner and Haydar, 2012), segregated into the VZ and SVZ, respectively (Kawaguchi et al., 2008). Apical IPs exhibit short radial bipolar morphology and sometimes contact the ventricular surface, while basal IPs usually exhibit multipolar morphology (Kowalczyk et al., 2009). Short radial progenitors were independently found by another approach, using reporter plasmids electroporated into VZ cells (Gal et al., 2006). Interestingly, the so-called “short neural precursors” (SNPs) showed electron microscopic evidence of apical (ventricular) surface contact. More recent work has confirmed that SNPs express Tbr2 (Tyler and Haydar, 2013). The classification of IPs into apical and basal types (Fig. 3A) is therefore supported by molecular and morphological correlations (Hevner and Haydar, 2012).

Figure 3. Molecular and cellular characteristics of intermediate progenitors (IPs).

(A) IPs are produced from apical (RG-a) and basal (RG-b) radial glia. IPs in the VZ exhibit short radial morphology and are attached to the ventricular/apical surface (IP-a), while IPs in the SVZ exhibit multipolar morphology with no apical attachment (IP-b). The IP-b cells extend highly dynamic processes, some of which approach the ventricular/apical surface (red arrowheads). IPs divide to produce migrating projection neurons (PN-m), which may also be derived directly from RG divisions. Differentiation from RG → IP → PN-m is associated with the sequential expression of transcription factors Pax6 → Tbr2 → Tbr1 (reviewed by Hevner et al., 2006). (B) Delta-Notch signaling may occur from RG → RG and from IP → RG. Dll1 is expressed by RG progenitors and IPs, while Dll3 is expressed only by IP-b cells. Dll1 on IPs is localized to processes as well as cell bodies, while Dll3 on IP-b cells is limited to the cell body. Dll1 expression on IP-b cell processes may mediate long-range Delta-Notch signaling (middle IP → RG interaction). Insets show enlarged views of contacts indicated by boxes.

Delta-Notch signaling by IPs

Canonical Notch receptor signaling is essential to maintain RG progenitor identity, and to thereby prevent the premature onset and cessation of cortical neurogenesis (Imayoshi et al., 2010). IPs play an essential role in this process (Yoon et al., 2008). Specifically, IPs highly express Notch receptor ligands Delta-like 1 (Dll1) on both apical and basal IPs, and Dll3 on basal IPs only (Kawaguchi et al., 2008; Nelson et al., 2013). Interestingly, Dll1 protein is highly expressed on IP processes, including long apical processes that extend from the SVZ to the VZ where they contact mitotic RG at the apical surface (Nelson et al., 2013). As demonstrated by time-lapse imaging, IP processes undergo rapid extension and retraction, suggesting involvement in cell migration (Tabata and Nakajima, 2003; Noctor et al., 2004) or, as the more recent evidence suggests (Nelson et al., 2013), Dll1-Notch signaling (Fig. 3B).

IP contributions to cortical layers

The hypothesis that IPs contribute predominantly to upper cortical layers (i.e., layers 2–4) was initially suggested by correlations between gene expression in the SVZ, where IPs are located, and in the upper (but not the lower) cortical layers. In particular, the expression patterns of Svet1 (subsequently identified as an Unc5d intron; Sasaki et al., 2008) and Cux2 supported this hypothesis (Tarabykin et al., 2001; Zimmer et al., 2004). This hypothesis seemed to accord with coordinate evolutionary expansion of the SVZ and upper cortical layers (Kriegstein et al., 2006). However, other observations suggested that IPs produce the majority of glutamatergic neurons in all cortical layers (Haubensak et al., 2004; Pontious et al., 2008; Kowalczyk et al., 2009). The contributions of IPs to cortical layers will ultimately have to be resolved by long-term lineage tracing of IPs to determine the laminar fates of daughter neurons. Preliminary studies using inducible conditional genetic lineage tracing in Eomes-CreER mice (Pimeisl et al., 2013) suggest that IPs indeed contribute to all cortical layers, including subplate and Cajal-Retzius neurons (R.F.H., data not shown). Similar observations have been made using the Tbr2:cre line (Vasistha et al., 2013). In future studies, it will be interesting to determine if early IPs diversify into lineages committed to upper and lower cortical layer identities, as described for early radial glia progenitors (Franco et al., 2012).

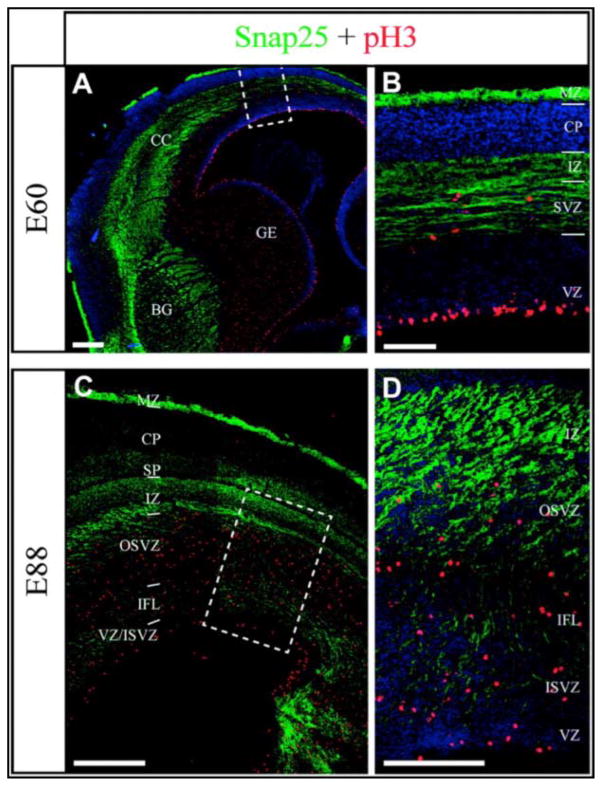

IP contributions to cortical expansion and folding during cortical evolution

Evolutionarily, IPs are thought to be instrumental in the expansion of neocortical thickness and surface area by amplifying the output from the cortical germinal zone (Cheung et al., 2010; Martinez-Cerdeno, 2006). In developing macaque and human cortices, Smart et al. (2002) identified cytoarchitectonically distinct subdivisions within the SVZ, designated the inner SVZ (ISVZ) and outer SVZ (OSVZ), separated from each other by an inner fiber layer. Garcia Moreno, Vasistha et al., (2012) examined a gyrencephalic rodent, the agouti (Dasyprocta agouti) and a lissencephalic primate, the marmoset monkey (Callithrix jacchus) and identified very similar cytoarchitectonic distinction between the OSVZ and ISVZ at midgestation in both species. Regardless of the brain folding, the proportions of radial glia, intermediate progenitors, and outer radial glial cell (oRG) populations were similar in the lissencephalic marmoset at midgestation as in gyrencephalic human or ferret (Garcia Moreno, Vasistha et al. 2012). Kelava and colleagues conducted similar study in the marmoset at midgestation (Kelava et al., 2012). These observations suggest that cytoarchitectonic subdivisions of SVZ are an evolutionary trend and not a primate specific feature, and that a greater population of oRG can be seen in larger brains regardless of phylogeny or cortical folding. Hevner and Haydar proposed that differential regulation of bRG and other progenitor types might enhance the adaptability and diversity of cortical morphogenesis (Hevner and Haydar, 2013). Recent studies in transgenic mice support this idea and confirm that IPs are critical in the genesis of cortical gyri and sulci (Nonaka-Kinoshita et al., 2013; Rash et al., 2013; Stahl et al., 2013).

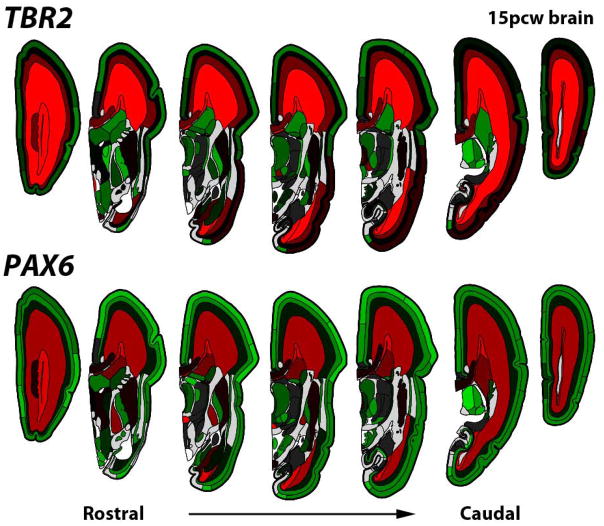

(4) Transcriptional Landscape of the Developing Human Cortex

Development of the cellular and functional architecture of the neocortex is to a large extent the product of tightly regulated gene transcriptions, and the unique features of human cortical function are presumably largely a function of differences in transcriptional regulation between species. A number of recent studies have begun to characterize the mouse, human and non-human primate cortical transcriptome to understand how gene expression relates to the development and functional organization of the neocortex (Abrahams et al., 2007; Johnson et al., 2009; Belgard et al., 2011; Colantuoni et al., 2011; Kang et al., 2011; Bernard et al., 2012; Hawrylycz et al., 2012). To understand these transcriptional programs and allow comparative analyses to identify similarities and differences between human and other species, the Allen Institute for Brain Science has over the last decade created a series of transcriptional atlases of the developing and adult human (Hawrylycz et al., 2012), non-human primate and mouse brains (Lein et al., 2007) as freely accessible data resources for the scientific community (available at www.brain-map.org). In the neocortex these atlases analyze the transcriptome at different levels of anatomical resolution and breadth spanning the laminar and areal extent of the cortex, and at different stages of cortical development. The Human Brain Atlas project uses DNA microarrays for transcriptional profiling of several hundred locations spanning the adult human neocortex (Hawrylycz et al., 2012), while the NIH Blueprint Non-Human Primate atlas profiles individual cortical layers in the rhesus monkey. Similarly, the BrainSpan project profiles the transcriptome across human brain development, using RNA-seq on discrete cortical regions across the entire lifespan, as well as with microarrays at higher resolution in the mid-gestational cortex on laser microdissected individual layers of different regions of the developing neocortex. These latter data allow analysis of the detailed anatomical distribution of transcripts in the prenatal human cortex, such as the expected enrichment of the neurogenic genes PAX6 and TBR2 in radial glia and intermediate progenitors of the ventricular and subventricular zones (Fig. 5). The availability of these data provides a rich resource for understanding neocortical development and identifying features that are distinct in human brain development.

Figure 5. Restricted expression of neurogenic genes PAX6 and TBR2 in the proliferative layers of the 15 post-conceptual week (pcw) mid-gestational human brain on coronal sections.

Normalized expression levels (red high, green low) from microarray analysis of individually isolated brain regions are plotted on anatomical parcellations of an age-matched digital reference atlas (www.brainspan.org).

Several broad themes about the transcriptional architecture of the neocortex emerge from analyses of these data. In the mature cortex, the greatest transcriptional variation is seen across cortical layers and major cell classes, representing differential expression across the different neuronal and non-neuronal cells making up the cortex (Belgard et al. 2011; Bernard et al., 2012). Relatively smaller variation is seen across cortical areas in the adult, reflecting the common stereotyped architecture of the neocortex as a whole, although there is a strong relationship between physical proximity and transcriptional similarity (Hawrylycz et al., 2012). These graded relationships across the cortex are reminiscent of early gradient expression of cortical transcription factors responsible for areal specification (O’Leary et al., 2007), suggesting that these early gradients leave a lasting imprint on the transcriptome as a whole.

Differences in cortical cytoarchitectural specializatons between primates and rodents have molecular correlates. For example, the highly specialized primary visual cortex (V1) in human and non-human primates shows distinctive gene expression patterns compared to other cortical regions (Bernard et al., 2012). This unique regional patterning in V1 is not recapitulated in rodent visual cortex. Looking more broadly in a comparative study of approximately 1000 genes in human and mouse cortex, nearly one third showed differences between species (Zeng et al., 2012).

(5) Role of environmental influences on the regionalisation of the mammalian cerebral cortex

The basic patterns of cortical areas are pre-programmed and develop from early cortical gradients; however, differences also begin to arise by local interactions with afferent neurons. Thalamic axons, which later will mediate most sensory information from the environment, reach the cortex at a very early stage, before the majority of cortical neurons have even been born (Molnár et al., 2012). Although the early cortical patterning is autonomous and established with or without the presence of external input, recent work points to the crucial role of the early-developing thalamocortical projections and their interactions with the developing cortical circuitry in establishing some aspects of the functional and structural organization of the cortex. Cortical areas and their thalamic input can be experimentally duplicated, increasing their number, by manipulating the expression of genes that control cortical patterning during development (e.g., Shimogori and Grove, 2005; Assimacopoulos et al., 2012).

Molnár et al. (2012) are interested in the signaling mechanisms that set the coordinates for the further establishment of cortical areas with their specific connections, including thalamic inputs. It is a fundamental question to understand what genetic and environmental interactions allocate cortical territories for the various sensory and motor representations during normal development and in pathological conditions (Grant et al., 2012). The effect of sensory deprivation on cortical development has been an important model to study the interaction between the unfolding genetic cortical developmental program and the environmental influence (Rakic, 1988; Dehay and Kennedy, 2007; Reillo et al., 2011). In this review the comparative studies on species with limited visual input shall be discussed in more detail. These species provide valuable models to study the contribution of sensory inputs to cortical specializations (Catania and Kaas, 1995; Catania and Remple, 2002; Němec et al., 2007).

Structure and Function of Subterranean Vision

Among mammals, approximately 300 species have adapted to the stable, low-oxygen and mainly lightless underground ecotope (Nevo, 1999). Eye sizes and degree of the visual system reduction vary substantially across subterranean mammals (Němec et al., 2007). Some strictly subterranean species such as the blind mole-rats of genus Spalax possess minute, subcutaneous eyes with degenerated optical apparatus and a vestigial visual system, the only function of which is to detect ambient light levels for photoperiodic perception (Nevo, 1999). Although the primary visual cortex (V1) is present in Spalax ehrenbergi, cortical visual processing is severely impaired by lack of retinotopic organization within the geniculo-striate pathway (Cooper et al. 1993). Moreover, no visually evoked potentials could be recorded in the occipital cortex (Haim et al., 1983; Necker et al., 1992). Instead, electrophysiological and 2-deoxiglucose mapping experiments revealed that occipital regions, which are occupied by visual cortex in sighted mammals, can be activated by somatosensory (Necker et al., 1992) and auditory stimuli (Heil et al., 1991; Bronchti et al., 2002).

Strictly subterranean, congenitally microphthalmic African mole-rats (Rodentia, Bathyergidae), by contrast, possess structurally normal eyes that have retained the capability of image-forming vision (Němec et al., 2008). They exhibit unique photoreceptor properties (Peichl et al., 2004). The rod dominated retina of the African mole-rats contain significant cone populations (~10%) expressing dominantly S-opsin, which seems to be sensitive to blue light in bathyergids (Kott et al., 2010). Many of these S cones co-express small amounts of L-opsin (sensitivity to green or yellow). Only few pure L cones express exclusively the L opsin. Although, behavioural experiments have confirmed that L-cones subserve green/green-yellow light sensing at photopic levels (Kott et al., 2010), an extremely sparse population of L cones likely contributes little to image-forming vision.

The total number of optic nerve fibres ranges between 6,000 in Bathyergus suillus and 2,100 in Heliophobius argenteocinereus (Němec et al., 2008). Visual acuity, estimated from counts of peak ganglion cell density and axial length of the eye, ranges between 0.3 and 0.5 cycles per degree (Němec et al., 2008). The central visual system of bathyergids has undergone regression (Němec et al., 2004; Crish et al., 2006). All the visual nuclei except the suprachiasmatic nucleus receive almost exclusively contralateral retinal projections. The only well developed visual domains are those involved in controlling the circadian and circannual biological rhythms – the suprachiasmatic nucleus and the retinohypothalamic projections. The lateral geniculate body is severely reduced in size, but still constitutes the major retinal target receiving about 60% of all retinal projections (Němec et al., 2008). The pretectum is also only moderately reduced. By contrast, the superficial visual layers of the superior colliculus and the accessory optic system are vestigial (Němec et al., 2001, 2004). This indicates that the bathyergid mole-rats are poorly equipped for the detection and orientation towards objects in the visual field, and for the tracking of moving objects.

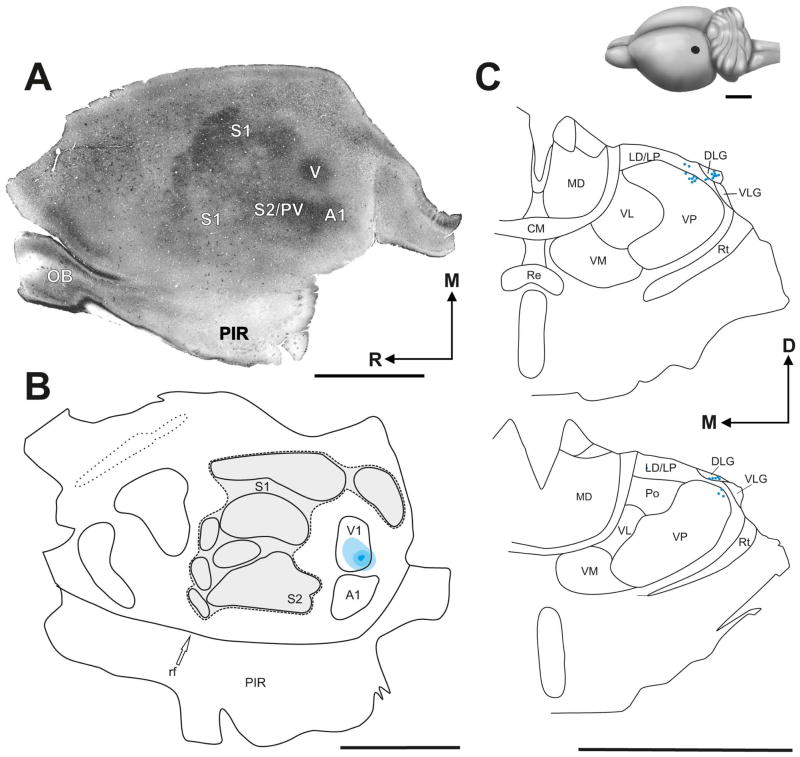

The primary visual cortex (V1) is small and, in comparison to other rodents, displaced laterally (Fig. 6). Such an unusual position appears to be a consequence of an expansion of the somatosensory cortex and might account for the failure of electrophysiological identification of V1 in Heterocephalus glaber (Catania and Remple, 2002; Henry et al., 2006). Multiple injections of different tracers in different regions of V1 resulted in retrograde labelling of a distinct region of the dorsal lateral geniculate nucleus (DLG), implying conservation of the retinotopic organization within the geniculo-striate pathway (Miklušová et al., unpublished data). However, many injections into putative V1 resulted also in a robust retrograde labeling of the multimodal thalamic nuclei, namely lateral posterior thalamic nucleus and posterior thalamic nucleus. Indeed, retrograde projections to these structures were often much stronger than those to the DLG. Thus, only part of the cytochrome oxidase-dense region in the in far caudolateral cortex seems to correspond to V1, the rest of the area likely belongs to associative cortex processing multimodal information. Another indication of the presence of a definable visual cortex comes from functional neuroanatomical mapping: Stimulation by light after a period of dark adaptation elicits c-Fos expression in the occipital cortex of Fukomys anselli (Oelschläger et al., 2000). Evolutionary reduction of the visual cortex in these strictly subterranean rodents seems to be coupled with expansion of the somatosensory cortex and with a robust multimodal thalamic input to the expected location of the primary visual cortex.

Figure 6. Primary visual cortex (V1) in Giant Mole Rat (Fukomys mechowii).

(A) Section of flattened cortex stained for cytochrome oxidase. Cytochrome oxidase (CO)-dense regions in the medial cortex and less obvious CO-dense modules in the lateral cortex likely correspond to the primary somatosensory cortex (S1), regions in far caudolateral cortex likely correspond to the secondary somatosensory cortex (S2), parietal ventral area (PV), and primary visual (V1) and auditory cortex (A1). (B, C) Anatomical identification of the V1. Injection of fluorescent tracer Fast Blue into a putative V1 resulted in retrograde labelling within the lateral geniculate nucleus (DGL), clear evidence for the presence of a primary visual cortex. The injection site is shown in (B), the resulting distribution of retrogradely labelled neurons is shown in (C). Note that retrogradely labelled neurons were also distributed over the adjacent laterodorsal and/or lateral posterior thalamic nucleus (LD/LP) and ventral posterior thalamic nucleus of the (VP). Upper right drawing of F. mechowii brain shows the relative size and location of the V1 (black oval). Its position is displaced laterally compared to other rodents. CM, central medial thalamic nucleus; D, dorsal; M, medial; MD, mediodorsal thalamic nucleus; R, rostral; OB, olfactory bulb; PIR, piriform cortex; Po, posterior thalamic nuclear group; Re, reuniens thalamic nucleus; rf, rhinal fissure; Rt, reticular thalamic nucleus; VL, ventrolateral thalamic nucleus; VM, ventromedial thalamic nucleus. Scale bars, 5 mm.

Summary

Comparative studies of the mammalian brain have revealed the level of cellular and laminar specialization that was present in early mammalian cortex.

Comparative developmental studies indicate that the elaboration and cytoarchitectonic compartmentalization of the germinal zone, with alterations in the proportions of various progenitor types correlates with the evolutionary enlargement of the mammalian cortex, but their relationship to brain folding is still not fully understood.

Tangential migration is employed in the delivery of various cell populations of the mammalian olfactory and cerebral cortex. This mechanism enabled the convergence of diverse glutamatergic and GABAergic neuronal populations to a specific cortical area where they organize themselves into complex neuronal circuits. Segregating neurogenesis in space and time produces cell diversity. Recent results suggests that some of the earliest generated cells of the cortex in marginal zone and subplate arrive through tangential migration to the cortex.

Transcriptome analysis of chick, mouse, human and non-human primate telencephalon help an understanding of how gene expression relates to the development and to the adult anatomical and functional organization of the neocortex. These expression data will have to be tested for causal relationships and integrated with more quantitative anatomical data on cortical neuronal cell numbers, proportions of cell types in particular area and layer to reveal the evolutionary changes in circuit assembly.

While various mammals share the basic layout of cortical areas and largely rely on early cortical gradients for the early differentiation, the particular areal proportions and distributions are driven by the sensory and motor experience during the individuals’ ontogenesis.

Figure 4.

Cytoarchitecture of the embryonic marmoset neocortical germinal zone is similar to that of developing primate brains that have convolutions (sulci and gyri). Snap25 immunoreactivity showed an extensive fiber layer at E60 (A–B) and E88 (C–D). A: At E60 Snap25 (green) immunoreactivity revealed a broad band of fiber fascicles crossing below the ganglionic eminence (GE) close to the anlage of the basal ganglia (BG) on coronal sections. B: The SVZ contained pH3+ nuclei (red). The VZ and CP showed relatively less fiber labelling at this stage. C: At E88 the Snap25+ fibers showed variations in their density and orientation in different layers. Subplate (SP), IZ, upper part of OSVZ, and internal fiber layer (IFL) contained fibers with parallel trajectories to the pial and ventricular surfaces. The fibers were perpendicular to the ventricular surface with the lower part of the OSVZ. The VZ contained relatively few labeled fibers. Scale bars: 200. Figure from García-Moreno, Vasistha et al., 2012.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful for Professor András Csillag and his team for organising 7thEuropean Conference on Comparative Neurology, Budapest Hungary. We thank Professor Ray Guillery and Professor Hans ten Donkelaar for editing our manuscript. ZM is supported by Medical Research Council, The Wellcome Trust and BBSRC UK; JHK is funded by National Institutes of Health (NIH) R01-NS16446. JADC’s work was supported by grant BFU2010-21377 from the Spanish Ministerio de Ciencia e Innovación; RFH is supported by NIH Grants R21 MH087070 and RO1 MH080766-S. PN’s work was supported by the Czech Science Foundation (206/09/1364, to PN).

References

- Abrahams BS, Tentler D Perederiy JV, Oldham MC, Coppola G, Geschwind DH. Genome-wide analyses of human perisylvian cerebral cortical patterning. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104(45):17849–17854. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0706128104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson SA, Eisenstat DD, Shi L, Rubenstein JLR. Interneuron migration from basal forebrain to neocortex: Dependence on Dlx genes. Science. 1997;278:474–476. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5337.474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angevine JB, Sidman RL. Autoradiographic study of cell migration during histogenesis of cerebral cortex in the mouse. Nature. 1961;192:766–768. doi: 10.1038/192766b0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Assimacopoulos S, Kao T, Issa NP, Grove EA. Fibroblast growth factor 8 1 the neocortical area map and regulates sensory map topography. J Neurosci. 2012;32:7191–7201. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0071-12.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayoub AE, Oh S, Xie Y, Leng J, Cotney J, Dominguez MH, Noonan JP, Rakic P. Transcriptional programs in transient embryonic zones of the cerebral cortex defined by high-resolution mRNA sequencing. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:14950–14955. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1112213108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azevedo FAC, Carvalho LRB, Grinberg LT, Farfel JM, Ferretti REL, Leite REP, Filho WJ, Lent R, Herculano-Houzel S. Equal numbers of neuronal and nonneuronal cells make the human brain an isometrically scaled-up primate brain. J Comp Neurol. 2009;513:532–541. doi: 10.1002/cne.21974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belgard TG, Marques AC, et al. A transcriptomic atlas of mouse neocortical layers. Neuron. 2011;71(4):605–616. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.06.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernard A, Lubbers L, et al. Transcriptional architecture of the primate neocortex. Neuron. 2012;73(6):1083–1099. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bronchti G, Heil P, Sadka R, Hess A, Scheich H, Wollberg Z. Auditory activation of ‘visual’ cortical areas in the blind mole rat (Spalax ehrenbergi) Eur J Neurosci. 2002;16:311–329. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2002.02063.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cameron DA, Middleton FA, Chenn A, Olson EC. Hierarchical clustering of gene expression patterns in the Eomes+ lineage of excitatory neurons during early neocortical development. BMC Neurosci. 2012;13:90. doi: 10.1186/1471-2202-13-90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catania KC, Kaas JH. Organization of the somatosensory cortex of the star-nosed mole. J Comp Neurol. 1995;351(4):549–567. doi: 10.1002/cne.903510406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catania KC, Remple MS. Somatosensory cortex dominated by the representation of teeth in the naked mole-rat brain. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99(8):5692–5697. doi: 10.1073/pnas.072097999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ceci ML, Pedraza M, De Carlos JA. Embryonic septum and ventral pallium, new sources of olfactory cortex. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(9):e44716. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0044716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheung AF, Kondo S, et al. The subventricular zone is the developmental milestone of a 6-layered neocortex: comparisons in metatherian and eutherian mammals. Cereb Cortex. 2010;20:1071–1081. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhp168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clowry G, Molnár Z, Rakic P. Renewed focus on the developing human neocortex. J Anat. 2010;217(4):276–288. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7580.2010.01281.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cobos I, Puelles L, Martínez S. The avian telencephalic subpallium originates inhibitory neurons that invade tangentially the pallium (dorsal ventricular ridge and cortical areas) Dev Biol. 2001;239(1):30–45. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2001.0422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colantuoni C, Lipska BK, et al. Temporal dynamics and genetic control of transcription in the human prefrontal cortex. Nature. 2011;478(7370):519–523. doi: 10.1038/nature10524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins CD, Airey DC, Young NA, Leitch DB, Kaas JH. Neuron densities vary across and within cortical areas in primates. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107(36):15927–15932. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1010356107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper HM, Herbin M, Nevo E. Visual system of a naturally microphthalmic mammal: The blind mole rat, Spalax ehrenbergi. J Comp Neurol. 1993;328:313–350. doi: 10.1002/cne.903280302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crish SD, Dengler-Crish CM, Catania KC. Central visual system of the naked mole-rat (Heterocephalus glaber) Anat Rec Part A. 2006;288A:205–212. doi: 10.1002/ar.a.20288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Carlos JA, O’Leary DDM. Growth and targeting of subplate axons and establishment of major cortical pathways. J Neurosci. 1992;12:1194–1211. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.12-04-01194.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Carlos JA, López-Mascaraque L, Valverde F. Dynamics of cell migration from the lateral ganglionic eminence in the rat. J Neurosci. 1996;16:6146–6156. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-19-06146.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dehay C, Kennedy H. Cell-cycle control and cortical development. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2007;8(6):438–450. doi: 10.1038/nrn2097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elsen GE, Hodge RD, Bedogni F, Daza RA, Nelson BR, Shiba N, Reiner SL, Hevner RF. The protomap is propagated to cortical plate neurons through an Eomes-dependent intermediate map. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110:4081–4086. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1209076110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Englund C, Fink A, Lau C, Pham D, Daza RA, Bulfone A, Kowalczyk T, Hevner RF. Pax6, Tbr2, and Tbr1 are expressed sequentially by radial glia, intermediate progenitor cells, and postmitotic neurons in developing neocortex. J Neurosci. 2005;25:247–251. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2899-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franco SJ, Gil-Sanz C, Martinez-Garay I, Espinosa A, Harkins-Perry SR, Ramos C, Müller U. Fate-restricted neural progenitors in the mammalian cerebral cortex. Science. 2012;337:746–749. doi: 10.1126/science.1223616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gal JS, Morozov YM, Ayoub AE, Chatterjee M, Rakic P, Haydar TF. Molecular and morphological heterogeneity of neural precursors in the mouse neocortical proliferative zones. J Neurosci. 2006;26:1045–1056. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4499-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- García-Moreno F, López-Mascaraque L, De Carlos JA. Origins and migratory routes of murine Cajal-Retzius cells. J Comp Neurol. 2007;500:419–432. doi: 10.1002/cne.21128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- García-Moreno F, López-Mascaraque L, De Carlos JA. Early telencephalic migration topographically converging into the olfactory cortex. Cereb Cortex. 2008;18:1239–1252. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhm154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- García-Moreno F, Vasistha NA, Trevia N, Bourne JA, Molnár Z. Compartmentalization of cerebral cortical germinal zones in a lissencephalic primate and gyrencephalic rodent. Cereb Cortex. 2012;22(2):482–492. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhr312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant E, Hoerder-Suabedissen A, Molnár Z. Development of the corticothalamic projections. Front Neurosci. 2012;6:53. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2012.00053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haim A, Heth G, Pratt H, Nevo E. Photoperiodic effects on thermoregulation in a “blind” subterranean mammal. J Exp Biol. 1983;107:59–64. doi: 10.1242/jeb.107.1.59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen DV, Rubenstein JL, Kriegstein AR. Deriving excitatory neurons of the neocortex from pluripotent stem cells. Neuron. 2011;70(4):645–660. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haubensak W, Attardo A, Denk W, Huttner WB. Neurons arise in the basal neuroepithelium of the early mammalian telencephalon: a major site of neurogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:3196–3201. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0308600100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawrylycz M, Lein E, et al. An anatomically comprehensive atlas of the adult human brain transcriptome. Nature. 2012;489(7416):391–399. doi: 10.1038/nature11405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heil P, Bronchti G, Wollenberg Z, Scheich H. Invasion of visual cortex by the auditory system in the naturally blind mole rat. Neuroreport. 1991;2:735–738. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199112000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henry EC, Remple MS, O’Riain MJ, Catania KC. Organization of somatosensory cortical areas in the naked mole-rat (Heterocephalus glaber) J Comp Neurol. 2006;495:434–452. doi: 10.1002/cne.20883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herculano-Houzel S, Collins C, Wong P, Kaas JH. Cellular scaling rules for primate brains. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:3562–3567. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0611396104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hevner RF. From radial glia to pyramidal-projection neuron: transcription factor cascades in cerebral cortex development. Mol Neurobiol. 2006;33:33–50. doi: 10.1385/MN:33:1:033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hevner RF, Haydar TF. The (not necessarily) convoluted role of basal radial glia in cortical neurogenesis. Cereb Cortex. 2012;22(2):465–468. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhr336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hevner RF, Hodge RD, Daza RA, Englund C. Transcription factors in glutamatergic neurogenesis: conserved programs in neocortex, cerebellum, and adult hippocampus. Neurosci Res. 2006;55:223–233. doi: 10.1016/j.neures.2006.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imayoshi I, Sakamoto M, Yamaguchi M, Mori K, Kageyama R. Essential roles of Notch signaling in maintenance of neural stem cells in developing and adult brains. J Neurosci. 2010;30:3489–3498. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4987-09.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Itoh Y, Moriyama Y, Hasegawa T, Endo TA, Toyoda T, Gotoh Y. Scratch regulates neuronal migration onset via an epithelial-mesenchymal transition-like mechanism. Nat Neurosci. 2013;16:416–425. doi: 10.1038/nn.3336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson MB, Kawasawa YI, et al. Functional and evolutionary insights into human brain development through global transcriptome analysis. Neuron. 2009;62(4):494–509. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2009.03.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaas JH. The evolution of brains from early mammals to humans. WIREs Cog Sci. 2013;4:33–45. doi: 10.1002/wcs.1206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang HJ, Kawasawa YI, et al. Spatio-temporal transcriptome of the human brain. Nature. 2011;478(7370):483–489. doi: 10.1038/nature10523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawaguchi A, Ikawa T, Kasukawa T, Ueda HR, Kurimoto K, Saitou M, Matsuzaki F. Single-cell gene profiling defines differential progenitor subclasses in mammalian neurogenesis. Development. 2008;135:3113–3124. doi: 10.1242/dev.022616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelava I, Reillo I, et al. Abundant occurrence of basal radial glia in the subventricular zone of embryonic neocortex of a lissencephalic primate, the common marmoset Callithrix jacchus. Cereb Cortex. 2012;22 (2):469–481. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhr301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kott O, Šumbera R, Němec P. Light perception in two strictly subterranean rodents: Life in the dark or blue? PLoS ONE. 2010;5:e11810. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0011810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kowalczyk T, Pontious A, et al. Intermediate neuronal progenitors (basal progenitors) produce pyramidal-projection neurons for all layers of cerebral cortex. Cereb Cortex. 2009;19:2439–2450. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhn260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kriegstein A, Noctor S, Martínez-Cerdeño V. Patterns of neural stem and progenitor cell division may underlie evolutionary cortical expansion. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2006;7:883–890. doi: 10.1038/nrn2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lein ES, Hawrylycz MJ, et al. Genome-wide atlas of gene expression in the adult mouse brain. Nature. 2007;445(7124):168–176. doi: 10.1038/nature05453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lui JH, Hansen DV, Kriegstein AR. Development and evolution of the human neocortex. Cell. 2011;146:18–36. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.06.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marín-Padilla M. Early prenatal ontogenesis of the cerebral cortex (neocortex) of the cat (Felis domestica). A Golgi study. I. The primordial neocortical organization. Z Anat Entwicklungsgesch. 1971;134(2):117–145. doi: 10.1007/BF00519296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez-Cerdeño V, Noctor SC, Kriegstein AR. The Role of Intermediate Progenitor Cells in the Evolutionary Expansion of the Cerebral Cortex. Cereb Cortex. 2006;16:i152–i161. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhk017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McConnell SK, Ghosh A, Shatz CJ. Subplate neurons pioneer the first axon pathway from the cerebral cortex. Science. 1989;245(4921):978–982. doi: 10.1126/science.2475909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Métin C, Alvarez C, Moudoux D, Vitalis T, Pieau C, Molnár Z. Conserved pattern of tangential neuronal migration during forebrain development. Development. 2007;134(15):2815–2827. doi: 10.1242/dev.02869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miquelajáuregui A, Valera-Echavarría A, et al. LIM-homeobox gene Lhx5 is required for normal development of Cajal-Retzius cells. J Neurosci. 2010;30(31):10551–10562. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5563-09.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyata T, Kawaguchi A, Saito K, Kawano M, Muto T, Ogawa M. Asymmetric production of surface-dividing and non-surface-dividing cortical progenitor cells. Development. 2004;131:3133–3145. doi: 10.1242/dev.01173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molnár Z. Evolution of cerebral cortical development. Brain Behav Evol. 2011;78(1):94–107. doi: 10.1159/000327325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molnár Z, Butt SJB. Best-laid schemes for interneuron origin of mice and men. Nature Neuroscience. 2013;16(11) doi: 10.1038/nn.3557. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molnár Z, Clowry G. Cerebral cortical development in rodents and primates. Prog Brain Res. 2012;195:45–70. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-444-53860-4.00003-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molnár Z, Garel S, López-Bendito G, Maness P, Price DJ. Mechanisms controlling the guidance of thalamocortical axons through the embryonic forebrain. Eur J Neurosci. 2012;35(10):1573–1585. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2012.08119.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy WJ, Pevzner PA, O’Brien JO. Mammalian phylogenomics comes of age. Trends Genet. 2004;20:631–639. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2004.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Necker R, Rehkämper G, Nevo E. Electrophysiological mapping of body representation in the cortex of the blind mole rat. Neuroreport. 1992;3:505–508. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199206000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson BR, Hodge RD, Bedogni F, Hevner RF. Dynamic interactions between intermediate neurogenic progenitors and radial glia in embryonic mouse neocortex: potential role in Dll1-Notch signaling. J Neurosci. 2013;33:9122–9139. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0791-13.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Němec P, Altmann J, Marhold S, Burda H, Oelschlager HHA. Neuroanatomy of magnetoreception: The superior colliculus involved in magnetic orientation in a mammal. Science. 2001;294:366–368. doi: 10.1126/science.1063351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Němec P, Burda H, Peichl L. Subcortical visual system of the african mole-rat Cryptomys anselli: To see or not to see? Eur J Neurosci. 2004;20:757–768. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2004.03510.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Němec P, Cvekova P, Benada O, Wielkopolska E, Olkowicz S, Turlejski K, Burda H, Bennett NC, Peichl L. The visual system in subterranean african mole-rats (Rodentia, Bathyergidae): Retina, subcortical visual nuclei and primary visual cortex. Brain Res Bull. 2008;75:356–364. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresbull.2007.10.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Němec P, Cvekova P, Burda H, Benada O, Peichl L. Visual systems and the role of vision in subterranean rodents: Diversity of retinal properties and visual system designs. In: Begall S, Burda H, Schleich CE, editors. Subterranean rodents: News from underground. Heidelberg: Springer; 2007. pp. 129–160. [Google Scholar]

- Nevo E. Mosaic evolution of subterranean mammals: Regression, progression and global convergence. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Noctor SC, Flint AC, Weissman TA, Dammerman RS, Kriegstein AR. Neuron derived from radial glial cells establishes radial units in neocortex. Nature. 2001;409:714–720. doi: 10.1038/35055553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noctor SC, Martínez-Cerdeño V, Ivic L, Kriegstein AR. Cortical neurons arise in symmetric and asymmetric division zones and migrate through specific phases. Nat Neurosci. 2004;7:136–44. doi: 10.1038/nn1172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nonaka-Kinoshita M, Reillo I, Artegiani B, Angeles Martínez-Martínez M, Nelson M, Borrell V, Calegari F. Regulation of cerebral cortex size and folding by expansion of basal progenitors. EMBO J. 2013;32:1817–1828. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2013.96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oelschläger HHA, Nakamura M, Herzog M, Burda H. Visual system labeled by c-Fos immunohistochemistry after light exposure in the ‘blind’ subterranean Zambian mole-rat (Cryptomys anselli) Brain Behav Evol. 2000;55:209–220. doi: 10.1159/000006653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Leary DDM, Chou S-J, Sahara S. Area patterning of the mammalian cortex. Neuron. 2007;56(2):252–269. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedraza M, De Carlos JA. A further analysis of olfactory cortex development. Fron Neuroanat. 2012;6:35. doi: 10.3389/fnana.2012.00035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peichl L, Němec P, Burda H. Unusual cone and rod properties in subterranean african mole-rats (Rodentia, Bathyergidae) Eur J Neurosci. 2004;19:1545–1558. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2004.03263.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pimeisl I-M, Tanriver Y, Daza RA, Vauti F, Hevner RF, Arnold H-H, Arnold SJ. Generation and characterization of a tamoxifen-inducible EomesCreER mouse line. Genesis. 2013;51:725–33. doi: 10.1002/dvg.22417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pontious A, Kowalczyk T, Englund C, Hevner RF. Role of intermediate progenitor cells in cerebral cortex development. Dev Neurosci. 2008;30:24–32. doi: 10.1159/000109848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rakic P. Mode of cell migration to the superficial layers of the fetal monkey neocortex. J Comp Neurol. 1972;145:61–84. doi: 10.1002/cne.901450105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rakic P. Specification of cerebral cortical areas. Science. 1988;241(4862):170–6. doi: 10.1126/science.3291116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rash BG, Tomasi S, Lim HD, Suh CY, Vaccarino FM. Cortical gyrification induced by fibroblast growth factor 2 in the mouse brain. J Neurosci. 2013;33:10802–10814. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3621-12.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reillo I, de Juan Romero C, García-Cabezas MÁ, Borrell V. A role for intermediate radial glia in the tangential expansion of the mammalian cerebral cortex. Cereb Cortex. 2011;21(7):1674–1694. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhq238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sasaki S, Tabata H, Tachikawa K, Nakajima K. The cortical subventricular zone-specific molecule Svet1 is part of the nuclear RNA coded by the putative netrin receptor gene Unc5d and is expressed in multipolar migrating cells. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2008;38:474–483. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2008.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimogori T, Grove EA. Fibroblast growth factor 8 regulates neocortical guidance of area-specific thalamic innervation. J Neurosci. 2005;25(28):6550–6560. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0453-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smart IH, Dehay C, Giroud P, Berland M, Kennedy H. Unique morphological features of the proliferative zones and postmitotic compartments of the neural epithelium giving rise to striate and extrastriate cortex in the monkey. Cereb Cortex. 2002;12(1):37–53. doi: 10.1093/cercor/12.1.37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stahl R, Walcher T, De Juan Romero C, et al. Trnp1 regulates expansion and folding of the mammalian cerebral cortex by control of radial glial fate. Cell. 2013;153:535–49. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.03.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tabata H, Nakajima K. Multipolar migration: the third mode of radial neuronal migration in the developing cerebral cortex. J Neurosci. 2003;23:9996–10001. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-31-09996.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamamaki N, Fujimori KE, Takauji R. Origin and routes of tangentially migrating neurons in the developing neocortical intermediate zone. J Neurosci. 1997;17:8313–8323. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-21-08313.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamamaki N, Nakamura K, Okamoto K, Kaneko T. Radial glia is a progenitor of neocortical neurons in the developing cerebral cortex. Neurosci Res. 2001;41:51–60. doi: 10.1016/s0168-0102(01)00259-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tarabykin V, Stoykova A, Usman N, Gruss P. Cortical upper layer neurons derive from the subventricular zone as indicated by Svet1 gene expression. Development. 2001;128:1983–1893. doi: 10.1242/dev.128.11.1983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tuorto F, Alifragis P, Failla V, Parnavelas JG, Gulisano M. Tangential migration of cells from the basal to the dorsal telencephalic regions in the chick. Eur J Neurosci. 2003;18(12):3388–3393. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2003.03059.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tyler WA, Haydar TF. Multiplex genetic fate mapping reveals a novel route of neocortical neurogenesis, which is altered in the Ts65Dn mouse model of Down syndrome. J Neurosci. 2013;33:5106–5119. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5380-12.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walsh C, Cepko CL. Clonal dispersion in proliferative layers of developing cerebral cortex. Nature. 1993;362(6421):632–635. doi: 10.1038/362632a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong P, Collins CE, Kaas JH. Overview of sensory systems of Tarsius. Int J Primatol. 2010;31:1002–1031. [Google Scholar]

- Yoon KJ, Koo BK, Im SK, Jeong HW, Ghim J, Kwon MC, Moon JS, Miyata T, Kong YY. Mind bomb 1-expressing intermediate progenitors generate notch signaling to maintain radial glial cells. Neuron. 2008;58:519–31. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng H, Shen EH, et al. Large-scale cellular-resolution gene profiling in human neocortex reveals species-specific molecular signatures. Cell. 2012;149(2):483–496. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.02.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmer C, Tiveron MC, Bodmer R, Cremer H. Dynamics of Cux2 expression suggests that an early pool of SVZ precursors is fated to become upper cortical layer neurons. Cereb Cortex. 2004;14:1408–1420. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhh102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]