Summary

Honey bee (Apis mellifera) entrance guards discriminate nestmates from intruders. We tested the hypothesis that the recognition cues between nestmate bees and intruder bees overlap by comparing their acceptances with that of worker common wasps, Vespula vulgaris, by entrance guards. If recognition cues of nestmate and non-nestmate bees overlap, we would expect recognition errors. Conversely, we hypothesised that guards would not make errors in recognizing wasps because wasps and bees should have distinct, non-overlapping cues. We found both to be true. There was a negative correlation between errors in recognizing nestmates (error: reject nestmate) and nonnestmates (error: accept non-nestmate) bees such that when guards were likely to reject nestmates, they were less likely to accept a nonnestmate; conversely, when guards were likely to accept a non-nestmate, they were less likely to reject a nestmate. There was, however, no correlation between errors in the recognition of nestmate bees (error: reject nestmate) and wasps (error: accept wasp), demonstrating that guards were able to reject wasps categorically. Our results strongly support that overlapping cue distributions occur, resulting in errors and leading to adaptive shifts in guard acceptance thresholds

Keywords: Nestmate recognition, cue distributions, Apis mellifera

Introduction

Social insects are popular organisms for the study of group level recognition, in which members are distinguished from non-members, because colonies normally possess entrance guards to recognize and exclude intruders, whilst allowing nestmates to enter (ants: Hölldobler and Wilson, 1990; wasps: Gamboa et al., 1996; termites: Wilson, 1971; and honey bees: Butler and Free, 1952; Moore et al., 1987). Within the social insects, the honey bee (Apis mellifera) is a popular study system (Getz, 1991; Breed et al., 2004a) because guard worker bees can encounter a variety of harmful intruders, specifically conspecific robbers from other honey bee colonies and allospecific intruders such as hornets (Vespa spp.) and wasps (Vespula spp) (de Jong, 1990; Ono et al., 1995; Breed et al., 2004b). While conspecific robber bees steal the victim colony’s stored honey during periods of nectar dearth (Free, 1977; Seeley, 1985), wasps take adult bees, brood, and honey. Both frequently kill the victim colony (Ono et al., 1995). Guard bees, with their ability to discriminate “friend from foe” (Lubbock, 1882), are therefore key to colony survival.

Guard honey bees intercept and examine incomers at the nest entrance (Butler and Free, 1952) and are thought to differentiate between nestmates and intruders by comparing the cues present on each incomer with a template representing the colony (Breed, 1987). The maximum acceptable amount of dissimilarity between the template and the cue is the acceptance threshold (Reeve, 1989). Increasing dissimilarity to the template should increase the probability of the incomer being rejected. If there were discrete categorical differences in the cues of nestmates and intruders, then the recognition system could, in principle, make no errors; all incomers would be correctly identified as either nestmate or intruder. If, however, the cues of nestmates and intruders overlap, where both insects possess qualitatively or quantitatively similar cues, then errors are inevitable because some intruders will be more similar to the template than some nestmates. Overlap will therefore lead to two types of errors: rejection errors, the classifying of nestmates as intruders; and acceptance errors, the classifying of intruders as nestmates (Reeve, 1989). Natural selection should favour a recognition system that minimizes the total cost of these two errors (Reeve, 1989; Sherman et al., 1997).

Cost is minimized by having a shifting acceptance threshold (Reeve, 1989). A permissive acceptance threshold is a threshold that accepts large differences from the template and will result in more acceptance errors and fewer rejection errors. It will be favoured when intruders are rare relative to nestmates, when the cost of admitting an intruder is low, and when the cost of excluding a nestmate is high. A non-permissive threshold is a threshold that accepts only small differences from the template and applies in the reverse circumstances. These predictions are supported by data. Honey bee guards become more accepting of non-nestmate bees as nectar availability changes from dearth to abundance, with robbing declining from frequent to non existent (Downs and Ratnieks, 2000).

Our study makes a novel test of the adaptive acceptance threshold hypothesis by investigating its major assumption, that the odour cue distributions, that is the absence and presence of certain compounds and their relative concentrations, of nestmates and non-nestmates overlap. The most rigorous way to show this would be to determine exactly which and how much of the chemical cues used in a nestmate’s acceptance profile (Breed, 1998; Breed et al., 2004c) exactly match which and how much of the chemical cues that are present on a conspecific non-nestmate. It is still, however, unclear which of the candidate chemicals and in what concentrations exactly constitute a colony-specific odour phenotype. An alternative approach is therefore needed.

Here we behaviourally test the assumption that the cues of nestmates and non-nestmates overlap by simultaneously determining the acceptance of nestmate worker bees, non-nestmate worker bees, and worker common wasps (Vespula vulgaris) by honey bee entrance guards. Because wasps are a different species, they should possess cues that allow guards to recognize them categorically with no errors, thereby showing that the recognition system can, in fact, be error free.

Materials and methods

Study organisms

Honey bee (A. mellifera) colonies studied were of mixed European race, predominantly the native subspecies A. m. mellifera. Colonies were queenright with approximately 10,000–30,000 workers and brood. Each colony was housed in a standard Langstroth hive of two boxes, either two deep boxes or one deep and one medium box. Hives had a 3.5 cm diameter circular entrance hole in the lower deep box immediately below which there was a horizontal wooden platform (20 cm wide×10 cm long) to facilitate observations of guard behaviour and the acceptance or rejection of introduced bees and wasps.

We used six hives. Four hives were experimental discriminator hives into which we introduced the nestmate worker bees, nonnestmate worker bees, and worker common wasps to observe if they were accepted or rejected by guards. The other two hives were sources of non-nestmate bees. Hives were not inspected, managed, or treated with smoke on study days. On a few occasions during the study, the hives were smoked and opened to carry out routine inspections. No data were collected for at least one day afterwards.

Common wasps (V. vulgaris) are native to Britain. Colonies have an annual cycle and are founded in the spring by a lone queen. The number of workers increases during the summer and peaks in early autumn (Spradbery, 1973; Edwards, 1980). Common wasps may be extremely abundant and can be a major problem to beekeepers in the UK, especially in late summer and early autumn when colonies reach peak population and attacks on honey bee colonies are most intense and can kill victim honey bee colonies (Archer, 2002).

Study site

This study was conducted at the Fulwood apiary, located within a large suburban garden in Sheffield, UK. The foraging range of the hives included the city of Sheffield and part of the Peak District National Park (Beekman and Ratnieks, 2000). Because the bees’ ability to forage as far away as 12 km (von Frisch, 1967; Seeley, 1995), this site allowed them access to heather blooming in the Peak District (Beekman and Ratnieks, 2000). Although foraging conditions in Britain vary greatly even from day to day due to the changeable weather, the end of the heather bloom in early September heralds the start of a permanent nectar dearth until the following spring. Collecting data during days of both high and low nectar availability was necessary because we needed to quantify guard behaviour on days with varying amounts of robbing threats (Downs and Ratnieks, 2000).

Data Collection

Acceptance and rejection by guards

Data were collected on 19 study days from 22 July to 18 October 2004 when the temperature was at least 13°C and foragers were active. We used a standard behavioural assay of discrimination by natural entrance guards (Downs and Ratnieks, 2000). Returning foragers without pollen loads were captured at hive entrances and placed in 50 ml plastic conical centrifuge tubes, a different tube for each hive to prevent possible cross-contamination of odours between nestmates and non-nestmates. We used new tubes each study day. We collected wasps while they foraged from the syrup feeder and stored them in their own plastic tube. We cooled the insects in a portable ice chest until they were able to move but not fly.

Using forceps, we placed one bee or wasp on the entrance platform of a discriminator colony and noted the reaction of the guards for three minutes. We scored the introduction as a rejection if the guards stung, grappled, pulled, or bit the introduced bee or wasp. We scored the introduction as acceptance if the introduced insect was left alone or allowed to enter the hive after being inspected by one or more guards. Any insect that was not inspected during the three minutes on the platform or that entered the colony without inspection was classed as an acceptance. In most cases (> 95 %), introduced bees were immediately contacted by guards and either accepted or rejected; rejections of wasps were especially quick and robust. The entrance observer was blind to the source of the introduced bees as recommended for recognition studies (Gamboa et al., 1991).

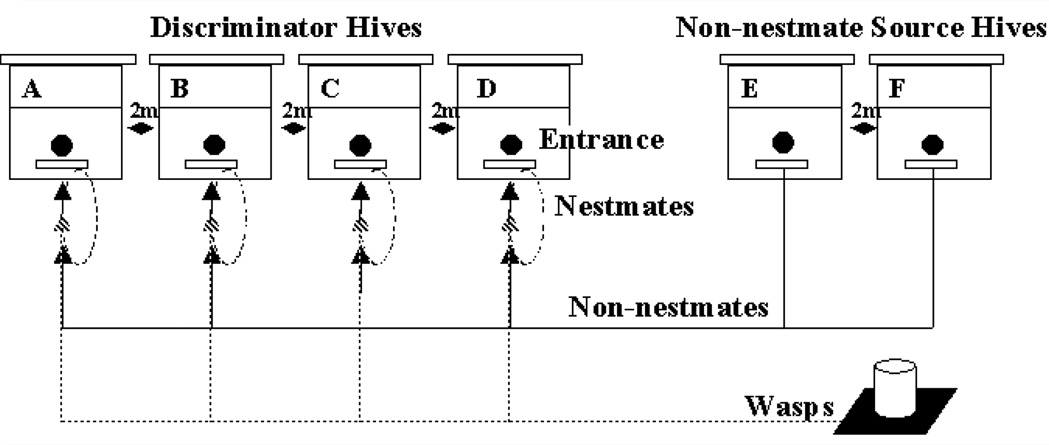

In one series of introductions, each of the four discriminator hives received four insects: one nestmate bee, one non-nestmate bee from each of two source hives, and one wasp. The three bees were introduced in random order and the wasp was introduced last because it caused some short-term increase in guarding activity. This procedure was repeated with the other three discriminator hives to give 16 introductions (Fig. 1). Depending on the duration of suitable weather conditions, four to eight series were completed per day. One series took approximately 50 minutes, allowing sufficient time between series for guard behaviour to return to baseline, which we also verified below by analyzing the non-significant effect of series on acceptance. Overall, we introduced 760 non-nestmate bees, 380 nestmate bees, and 380 wasps.

Fig. 1.

One series of introductions. Hives were at least 2m apart, including between discriminator and non-nestmate source hives. The entrance of each of the four discriminator hives received one nestmate worker bee (dashed line, solid arrow), one non-nestmate worker bee from source hive E and one from source hive F (solid line, solid arrow), and one worker common wasp collected from a syrup feeder (patterned line, patterned arrow). The behaviour of the guards to the introduced insect was observed and classified as either “accept” or “reject”.

Quantifying intrusion and guarding intensities

To quantify intrusions for both wasps and bees, we spent one hour each day (15 minutes per discriminator hive) observing the hive entrances and noting how many natural wasp intrusions and bee-bee fights were seen on the platform. Because non-nestmate and nestmate bees cannot be distinguished by eye, we could not quantify their intrusions directly. Counting the number of observed conspecific fights provided an indirect measure.

We quantified guarding levels by counting the number of guards present on the platform of the four discriminator hives at the start of each series of introductions. Guard bees were initially identified by their characteristic posture of standing with their forelegs off the ground and antennae facing forward (Butler and Free, 1952; Moore et al., 1987). Identification was verified by other guard behaviours including remaining on the entrance platform rather than flying off, walking in front of the entrance, and behaving aggressively towards intruders.

Demonstrating the use of olfactory cues

Guards can potentially detect intruders via any cues that vary from those of nestmates. Although odour cues are considered to be of primary importance, vision might possibly be used in the recognition of common wasp workers because they are a different body colour (yellow and black) to the bees (black). To clarify this issue, we carried out a small experiment to test the acceptance and rejection of common wasp workers and nestmate and non-nestmate honey bee workers by honey bee guards at the hive entrance in light and dark conditions. Data were collected in October 2005 from three more hives, each receiving seven insects in each treatment to give a total of 21 introductions in each of six treatments. For the light condition, introductions were performed as previously described. For dark, we covered the entrance platform with cardboard to block out light except for a small window of red light-filter plastic that eliminates wavelengths below ~ 600 nm (182 Light Red Filter; Lee Filters, UK).

Insects were introduced using the assay described above. Bees are blind to red light (Briscoe and Chittka, 2001), and this allowed us to observe and quantify the behaviour of guards whilst the guard bees were in the dark.

All data were not normally distributed. Non-parametric tests were carried out using Minitab statistical software (Version 14). 228 Couvillon, Roy, Ratnieks

Results

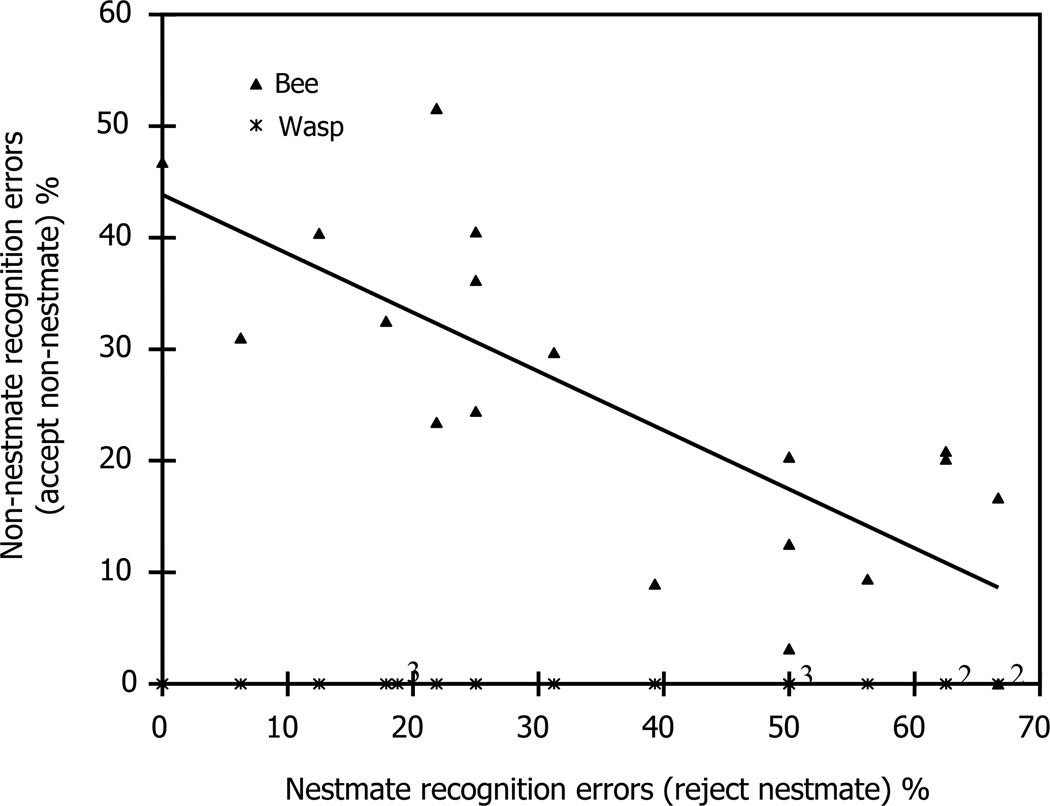

Fig. 2 presents the recognition errors from the four discriminator colonies. For each study day, we took the averages of the four hives for the two types of errors (nestmate rejection errors and nonnestmate acceptance errors). As guard turnover is quite rapid (Breed and Rogers, 1991) in a honey bee colony, each day we tested recognition errors using new guards. Analysis was therefore done on the 19 independent study days. Pooling the data each day allowed us to take into account variation between and within each hive.

Fig. 2.

Recognition errors by guard honey bees on the 19 study days. Errors are reject nestmate bees (x-axis) and accept non-nestmate bees or wasps (y-axis). Points are pooled data from the four study hives per day. Triangles represent errors in the recognition of nestmate bees versus non-nestmate bees, where each triangle represents 16–32 nestmate bee introductions per day and twice that number of non-nestmate bee introductions per day. Stars represent errors in the recognition of nestmate bees versus non-nestmate wasps, where each star represents 16–32 nestmate bee introductions per day and 16–32 wasp introductions per day. Numbers indicate data points when more than one point occurred in the same position. The line is the least squares regression (y = − 0.53x + 43.8) and R2 = 0.60.

There is a significant negative relationship between nestmate recognition error (reject nestmate bee) and conspecific non-nestmate recognition error (accept non-nestmate bee) (Spearman’s rank correlation for non-parametric data, rs= −0.595, p = 0.007). We also tested this correlation per hive and found that the negative trend was present in all four hives (Spearman’s rank correlation for nonparametric data, Hive A: rs = −0.528, p = 0.02; Hive B: rs = −0.514, p = 0.02; Hive C: rs = −0.624, p = 0.004). The decreased sample sizes reduced statistical power, however, and although the trend was present in the correct direction in the fourth hive, it was nonsignificant (Spearman’s rank correlation for non-parametric data, Hive D: rs = −0.203, p = 0.40).

In stark contrast to recognition errors of nestmates and conspecific non-nestmate worker bees, Fig. 2 also shows that every one of the 380 introduced wasps was rejected, demonstrating the complete absence of recognition errors by honey bee guards towards common wasps. Recognition errors between nestmate bees and wasps were therefore not correlated.

Additionally, there was no affect of series within a study day for either nestmate (Binary Logistic Regression, Odds Ratio = 0.93, p = 0.21) or non-nestmate (Binary Logistic Regression, Odds Ratio = 1.12, p = 0.1) worker bees, demonstrating that the guards did not become more prone to rejection by the end of a study day.

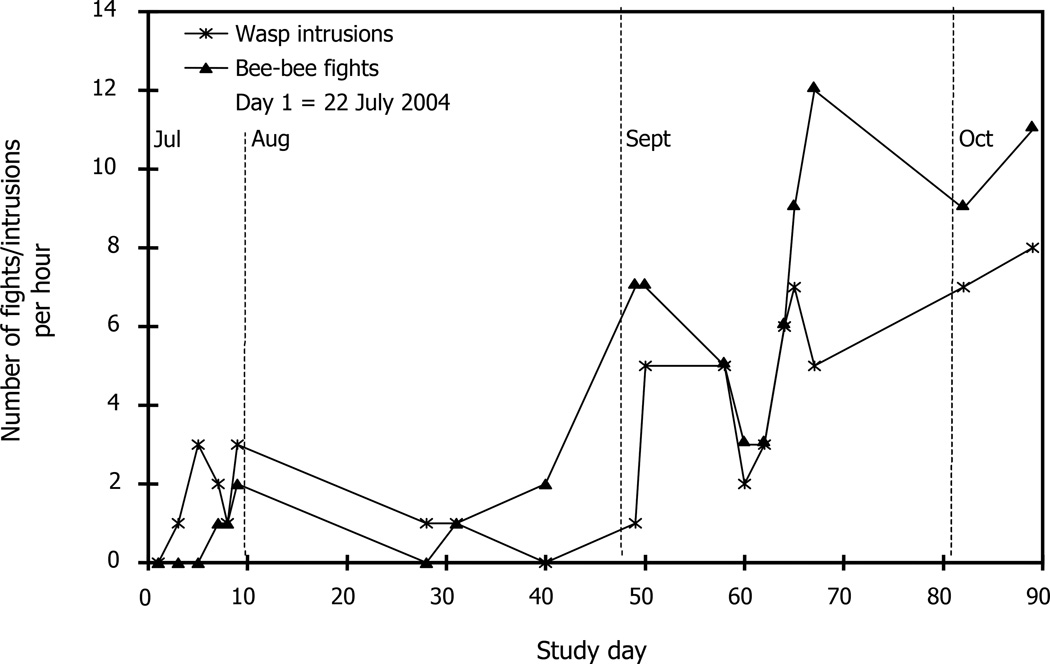

Fig. 3 shows the number of conspecific fights and wasp intrusions per hour on each study day. As expected, both increased from summer to autumn (Fig. 3). We expected more wasp intrusions later in the season because common wasp colonies reach their maximum size in early autumn. We expected more robbing by conspecifics in autumn, due to there being fewer flowers.

Fig. 3.

Number of observed wasp (star) intrusions and conspecific (triangle) fights per hour of hive entrance observation. Dashed lines indicate the calendar months. Data pooled across all four discriminator hives per study day.

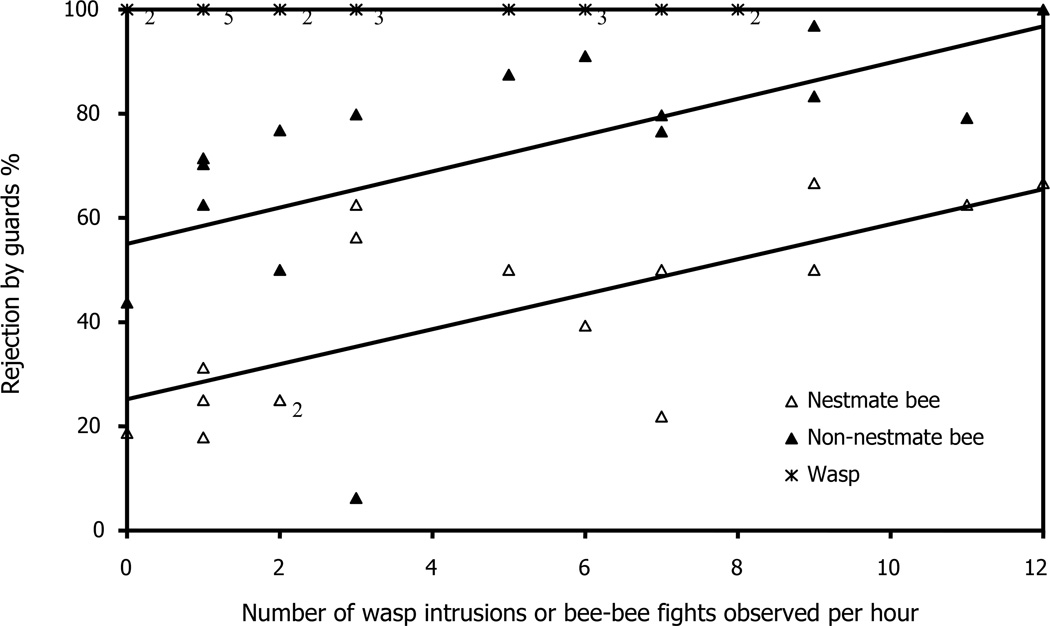

Fig. 4 shows that there is a strong positive correlation between the rejection of nestmate workers and the rate of conspecific fights (Spearman’s rank correlation for non-parametric data, rs = 0.732, p = 0.001) and the rejection of non-nestmates and the rate of conspecific fights (Spearman’s rank correlation, rs = 0.737, p=0.001). However, even though wasp intrusions, like conspecific fights, rose from summer to autumn (Fig. 3), there was no correlation between the number of intrusions by wasps per study day and the probability that a wasp would be accepted by the guards because wasps were always rejected.

Fig. 4.

Number of wasp intrusions or bee-bee fights observed per hour versus % rejection by guards. Wasp intrusions observed per hour versus wasp % rejection (stars), conspecific fights observed per hour versus non-nestmate bee % rejection (filled triangle) and nestmate bee (open triangle) % rejection. Subscript numbers indicted multiple data points. Data pooled with all 4 hives per study day. Line is least squares regression for non-nestmate (y = 3.48x + 55.0) and nestmate (y = 3.36x + 25.2) bees.

The light/dark experiment showed clearly that there was no difference in the probability of rejection by guards in the light versus in the dark for any of the three categories of insects introduced. The rejection of wasps was 100% in both light and dark (21/21, 20/20; Fisher’s Exact Test, p>0.99). The only difference was that in the light, all 21 were contacted by guards, whereas in the dark, one of the introduced wasps was not contacted within the three minutes. The rejection rates for nestmates in light and dark were 24% and 19% (5/21, 4/21, χ2 test, p = 0.71, df = 1). The rejection rate for nonnestmate bees in light and dark were 38% and 43% (8/21, 9/21, χ2 test, p = 0.75, df = 1).

Discussion

We found no correlation in the error rates made by guards when presented with nestmate bees (rejection error: reject nestmate bee) versus wasps (acceptance error: accept wasp), whereas there was a negative correlation in the errors relating to nestmate bees (rejection error: reject nestmate bee) versus non-nestmate bees (acceptance error: accept non-nestmate bee). These data strongly support the hypothesis that whilst the cue distributions of nestmates and allospecific non-nestmates (wasps) are distinct, the cue distributions of nestmates and conspecific non-nestmates overlap. Because of this overlap of cues, discrimination between nestmates and conspecific non-nestmates is challenging. The overlap leads to unavoidable errors in recognition, and ultimately to adaptively shifting acceptance thresholds. This we demonstrated with the negative correlation in the errors in the recognition of nestmate and non-nestmate bees compared to the absence of recognition errors for wasps (Fig. 2). If the cue distributions of nestmate and non-nestmate bees were also distinct, guards should have been able to reject all the non-nestmate bees, similar to the universal rejection of wasps that we observed. Although previous work has assumed an overlap in the cue distribution of nestmates and conspecific non-nestmates (Getz, 1981; Lacy and Sherman, 1983; Getz and Page, 1991), this study provides direct support for this assumption.

Wasps are always rejected, and the rejection rate of wasps was not correlated with the rejection rate of nestmate bees or the rate of wasp intrusions. Wasps were even rejected in July when intrusions were infrequent. Because the common wasp has an annual cycle with lone queens founding new colonies in spring, colonies are relatively small in July and did not reach maximum population until early autumn (Spradbery, 1973). Thus, we expected increased rates of V. vulgaris intrusions from July to October, and this is what we found. The average number of wasp fights rose from 1.33 per hour in late July to 6.67 per hour in late September and early October (Fig. 3). This increase in intrusions did not, however, affect wasp rejection rates by guard bees because wasps were always rejected (Fig. 4).

Given that the acceptance threshold is under selection to respond to nectar availability and, likewise, the probability of conspecific robbing, we predicted that during nectar dearth, there would be more 230 Couvillon, Roy, Ratnieks non-nestmate encounters and less permissive guarding. We therefore quantified attempted robbing by non-nestmate bees indirectly by counting the number of conspecific fights observed on the entrance platform. The frequency of intrusion by non-nestmate bees was higher during autumn than summer. The average number of conspecific entrance fights in three days of data collection at the end of July was 1.33 per hour. This increased during August and September, reaching 10.67 per hour during the last three days of data collection (26 September, 11 and 18 October) (Fig. 3). This increase in non-nestmate intrusions corresponds to an increase in non-nestmate rejections. Fig. 4 demonstrates the high correlation between rejection of nestmate and non-nestmate bees and the number of conspecific fights observed on the platform per one hour observation. Honey bee colonies respond to the increased frequency of intrusions by increasing the number of guards, as previously reported (Downs and Ratnieks, 2000). We observed that the mean number of guards per hive rose from four in July to nine in October (data not shown).

Although a recognition acceptance threshold is applicable to any sensory modality (olfactory, visual, tactile, or in combination), nestmate recognition in social insects is generally assumed to be olfactory (Getz, 1982; Lacy and Sherman, 1983; Howard, 1993; Breed et al.; 1998, Breed et al., 2004a; Wood and Ratnieks, 2004), with cuticular hydrocarbons playing a major role (Howard, 1993; Lorenzi et al., 1996). Our light/dark experiment supports the importance of olfaction in nestmate recognition. Guards accepted the same proportion of nestmate bees, non-nestmate bees, and wasps in both the light and the dark. The importance of olfaction and the transferability of odour cues were previously supported in an experiment whereby nestmate worker bees, kept in tubes that previously held wasps, were rejected by their own colony (Wood and Ratnieks, 2004). Although vision seems not to be crucial in deciding whether to accept or reject an incoming insect, however, it is almost certainly helpful for guards to see the incomers in the first place. It was our impression that guards in the red light treatment that were unable to see the introduced insect needed to literally stumble across it to be aware of its presence. Guard honey bees at a normal nest entrance during daytime appear to be visually aware of the insects around them; they turn towards and approach nearby insects.

Many different types of molecules are found on the insect cuticle, but cuticular hydrocarbons are considered important in nestmate recognition in social insects. Analyses show that their composition varies less within a colony than between different colonies (Breed et al., 1998; Singer, 1998). Of the different categories of hydrocarbons, alkenes might be of more biological relevance than alkanes (Dani, 2005), and workers have been shown to be able to discriminate alkenes better than alkanes (Chaline et al., 2005). Of interest to us, however, would be compounds that differ between the cuticles of honey bee and the common wasp workers (Butts et al., 1991; Steinmetz et al., 2003, Dani et al., 2004; Dani, 2005). Although there is some overlap of chemicals, many are found on one or the other. One or more of these could be used to categorically recognize wasp intruders.

Universal rejection could occur via one of two underlying mechanisms of cue dissimilarity. In one, guards could learn a nestmate template, allowing them to reject all other species of insects, such as the common wasp, that are sufficiently different from this template. In the other, a honey bee guard could instinctively recognize a particular odour that categorically signifies a threat to the colony. The latter mechanism would only evolve for intruder species that have exerted strong selective pressure for many generations. For example, a pheromone from the giant Japanese hornet (Vespa mandarinia japonica) is recognized by sympatric Japanese honey bees (A. cerana japonica) as the hornet is a major predator for this bee, but allopatric A. mellifera does not respond to this pheromone (Ono et al., 1995). Common wasps are sympatric with A. mellifera in Europe and are a serious threat for them. It is possible, therefore, that one or more chemicals in the cuticle of common wasps allow them to be recognized specifically by the honey bee guards. Further research is needed to determine whether honey bee guards reject other species of insects that do not represent a threat, as readily as they do common wasps.

Our study strongly indicates that the cues used by guard honey bee workers to discriminate between nestmate and non-nestmate bees overlap, but those used in recognizing common wasps are distinct. A challenge for future research is to determine the chemical nature of the cues used to make these recognition decisions and to understand how errors can be made.

Acknowledgements

MJC was funded by a Graduate Research Fellowship from the National Science Foundation, USA.

References

- Archer ME. The wasps, ants and bees (Hymenoptera: Aculeata) of Watsonian Yorkshire. Weymouth, UK: Yorkshire Naturalists' Union; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Beekman M, Ratnieks FLW. Long-range foraging by the honey bee. Apis mellifera L. Functional Ecology. 2000;14:490–496. [Google Scholar]

- Breed MD. Recognition pheromones of the honey bee. Bioscience. 1998;48:463–470. [Google Scholar]

- Breed MD, Bennett B. Kin recognition in highly eusocial insects. In: Fletcher DJC, Michener CD, editors. Kin Recognition in Animals. Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Breed MD, Rogers KB. The behavioural genetics of colony defence in honey bees - genetic variability for guarding behaviour. Behaviour Genetics. 1991;21:295–303. doi: 10.1007/BF01065821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breed MD, Leger EA, Pearce AN, Wang YJ. Comb wax effects on the ontogeny of honey bee nestmate recognition. Animal Behaviour. 1998;55:13–20. doi: 10.1006/anbe.1997.0581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breed M, Diaz P, Lucero K. Olfactory information processing in honey bee, Apis mellifera, nestmate recognition. Animal Behaviour. 2004a;68:921–928. [Google Scholar]

- Breed M, Guzman-Novoa E, Hunt G. Defensive behaviour of honey bees: organization, genetics, and comparisons with other bees. Annual Review of Entomology. 2004b;49:271–298. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ento.49.061802.123155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breed MD, Perry S, Bjostad LB. Testing the blank slate hypothesis: why honey bee colonies accept young bees. Insectes Sociaux. 2004c;51:12–16. [Google Scholar]

- Briscoe AD, Chittka L. The evolution of colour vision in insects. Annual Review of Entomology. 2001;46:471–510. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ento.46.1.471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butler CG, Free JB. The behaviour of worker honey bees at the hive entrance. Behaviour. 1952;4:262–292. [Google Scholar]

- Butts DP, Espelie KE, Hermann HR. Cuticular hydrocarbons of four species of social wasps in the Subfamily Vespinae - Vespa crabro L, Dolichovespula maculata (L), Vespula squamosa (Drury), and Vespula maculifrons (Buysson) Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology B-Biochemistry & Molecular Biology. 1991;99:87–91. [Google Scholar]

- Chaline N, Sandoz J-C, Martin SJ, Ratnieks FWL, Jones GR. Learning and discrimination of individual cuticular hydrocarbons by honey bees (Apis mellifera) Chemical Senses. 2005;30:327–335. doi: 10.1093/chemse/bji027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dani F, Corsi S, Pradella D, Jones G, Turillazzi S. GC-MS analysis of the epicuticle lipids of Apis mellifera reared in central Italy. Insect Social Life. 2004;5:103–109. [Google Scholar]

- Dani FR, Jones GR, Corsi S, Beard R, Pradella D, Turillazzi S. Nestmate recognition cues in the honey bee: differential importance of cuticular alkanes and alkenes. Chemical Senses. 2005;30:477–489. doi: 10.1093/chemse/bji040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De jong D. Insects: Hymenoptera (ants, wasps, and bees) In: Morse RA, Nowogrodzki R, editors. Honey bee pests, predators and diseases. Ithaca, New York, USA: Cornell University Press; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Downs SG, Ratnieks FLW. Adaptive shifts in honey bee (Apis mellifera L.) guarding behaviour support predictions of the acceptance threshold model. Behavioural Ecology. 2000;11:326–333. [Google Scholar]

- Edwards R. Social wasps: their biology and control. East Grinstead, UK: Rentokil Ltd.; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Free JB. The social organization of honey bees. London, UK: Edward Arnold; 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Gamboa G, Reeve H, Holmes W. Conceptual issues and methodology in kin-recognition research - a critical discussion. Ethology. 1991;88:109–127. [Google Scholar]

- Gamboa G, Grudzien T, Espelie K, Bura E. Kin recognition pheromones in social wasps: combining chemical and behavioural evidence. Animal Behaviour. 1996;51:625–629. [Google Scholar]

- Getz WM. Genetically based kin recognition systems. Journal of Theoretical Biology. 1981;92:209–226. [Google Scholar]

- Getz WM. An analysis of learned kin recognition in Hymenoptera. Journal of Theoretical Biology. 1982;99:585–597. [Google Scholar]

- Getz WM. The honey bee as a model kin recognition system. In: Hepper PG, editor. Kin Recognition. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Getz WM, Page RE. Chemosensory kin-communication systems and kin recognition in honey bees. Ethology. 1991;87:298–315. [Google Scholar]

- Hölldobler B, Wilson EO. The ants. Cambridge, Massachusetts, USA: Harvard University Press; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Howard RW. Cuticular hydrocarbons and chemical communication. In: Stanley-samuelson DW, Nelson DR, editors. Insect Lipids: Chemistry, Biochemistry and Biology. Lincoln, Nebraska, USA: University of Nebraska Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Lacy RC, Sherman PW. Kin recognition by phenotype matching. American Naturalist. 1983;121:489–512. [Google Scholar]

- Lorenzi M, Bagneres A, Clement J. The role of cutiuclar hydrocarbons in social insects: is it the same in paper-wasps? In: Turillazzi SWE, West-eberard MJ, editors. Natural history and evolution of paper wasps. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Lubbock SJ. Ants, bees and wasps: a record of observations on the habits of the social Hymenoptera. London, UK: Kegan Paul, Trench, Trubner & Co., Ltd.; 1882. [Google Scholar]

- Moore A, Breed M, Moor M. The guard honey bee - ontogeny and behavioural variability of workers performing a specialized task. Animal Behaviour. 1987;35:1159–1167. [Google Scholar]

- Ono M, Igarashi T, Ohno E, Sasaki M. Unusual thermal defence by a honey bee against mass attack by hornets. Nature. 1995;377:334–336. [Google Scholar]

- Reeve HK. The evolution of conspecific acceptance thresholds. American Naturalist. 1989;133:407–435. [Google Scholar]

- Seeley TD. Honey bee ecology. Princeton, New Jersey, USA: Princeton University Press; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Seeley TD. The wisdom of the hive. Cambridge, Massachusetts, USA: Harvard University Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Sherman PW, Reeve HK, Pfennig DW. Recognition systems. In: Krebs JR, Davies NB, editors. Behavioural Ecology. Oxford, UK: Blackwell Science; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Singer TL. Roles of hydrocarbons in the recognition systems of insects. American Zoologist. 1998;38:394–405. [Google Scholar]

- Spradbery JP. Wasps: an account of the biology and natural history of solitary and social wasps. London, UK: Sidgwick and Jackson; 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Steinmetz I, Schmolz E, Ruther J. Cuticular lipids as trail pheromone in a social wasp. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London Series B-Biological Sciences. 2003;270:385–391. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2002.2256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Von frisch K. The dance language and orientation of bees. Cambridge, Massachusetts, USA: Harvard University Press; 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson EO. The Insect Societies. Cambridge, Massachusetts, USA: Harvard University Press; 1971. [Google Scholar]

- Wood M, Ratnieks F. Olfactory cues and Vespula wasp recognition by honey bee guards. Apidologie. 2004;35:461–468. [Google Scholar]