Abstract

Diverse pluripotent stem cell lines have been derived from the mouse, including embryonic stem cells (ESCs), induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs), embryonal carcinoma cells (ECCs), and epiblast stem cells (EpiSCs). While all are pluripotent, these cell lines differ in terms of developmental origins, morphology, gene expression, and signaling, indicating that multiple pluripotent states exist. Whether and how the pluripotent state influences the cell line's developmental potential or the competence to respond to differentiation cues could help optimize directed differentiation protocols. To determine whether pluripotent stem cell lines differ in developmental potential, we compared the capacity of mouse ESCs, iPSCs, ECCs, and EpiSCs to form trophoblast. ESCs do not readily differentiate into trophoblast, but overexpression of the trophoblast-expressed transcription factor, CDX2, leads to efficient differentiation to trophoblast and to formation of trophoblast stem cells (TSCs) in the presence of fibroblast growth factor-4 (FGF4) and Heparin. Interestingly, we found that iPSCs and ECCs could both give rise to TSC-like cells following Cdx2 overexpression, suggesting that these cell lines are equivalent in developmental potential. By contrast, EpiSCs did not give rise to TSCs following Cdx2 overexpression, indicating that EpiSCs are no longer competent to respond to CDX2 by differentiating to trophoblast. In addition, we noted that culturing ESCs in conditions that promote naïve pluripotency improved the efficiency with which TSC-like cells could be derived. This work demonstrates that CDX2 efficiently induces trophoblast in more naïve than in primed pluripotent stem cells and that the pluripotent state can influence the developmental potential of stem cell lines.

Introduction

Pluripotent stem cell lines have been derived from diverse sources and include mouse and human germ cell tumor-derived embryonal carcinoma cells (ECCs) [1], mouse and human preimplantation epiblast-derived embryonic stem cells (ESCs) [2–4], mouse postimplantation epiblast-derived epiblast stem cells (EpiSCs) [5,6], and mouse and human mature cell-derived induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) [7]. All these pluripotent stem cell lines are capable of self-renewal and differentiating to embryonic germ layer derivatives. However, it has long been appreciated that there are differences in the morphology, gene expression, and pathways that regulate self-renewal and differentiation among these pluripotent stem cell lines [8]. In addition, both human and mouse ESCs and iPSCs can exist in either of two pluripotent states, termed ground state and naïve pluripotency [9–11]. Recent studies have begun to investigate whether differences in the pluripotent state influence each cell line's ability to reproducibly differentiate into specific lineages during directed in vitro differentiation [9,12,13]. Resolving the differences in in vitro differentiation among these cell types will critically inform the decision as to whether new stem cell models are equivalent to or can effectively replace ESCs as both a model for basic biology and as a tool for regenerative medicine.

The mouse provides a powerful system for resolving differences in developmental potential among pluripotent stem cell lines because the developmental potential of mouse pluripotent cell lines can be evaluated with reference to mouse development. During mouse development, the first two lineage decisions establish the pluripotent epiblast and two extraembryonic tissues: the trophectoderm (TE) and the primitive endoderm (PE). The epiblast will give rise to the fetus and contains progenitors of ESCs. The TE lineage will give rise to placenta, and trophoblast stem cells (TSCs) can be derived from the TE in the presence of fibroblast growth factor-4, Heparin (FGF4/Hep), and a feeder layer of mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) [14]. The PE will give rise to yolk sac, and extraembryonic endoderm (XEN) stem cells can be derived from the PE [15]. Knowledge of signaling pathways and transcription factors that reinforce these three lineages in the blastocyst has pointed to ways to alter the developmental potential of the stem cell lines derived from the blastocyst's lineages. For example, ESCs can be converted to TSCs by overexpressing the TE-specific transcription factor CDX2 in TSC medium [16] and by other means [17–21]. Importantly, overexpression of Cdx2 in ESCs leads to TSC-like cells with highly similar morphology, developmental potential, and gene expression as embryo-derived TSCs [16,22,23]. Similarly, TSCs can be converted to ESC-like iPSC by overexpressing Oct4 [24,25]. Likewise, ESCs can be converted to XEN cells using growth factors or PE transcription factors [12,26–29]. Interestingly, differences in the pluripotent state influence the ability of pluripotent stem cell lines to give rise to XEN cell lines [12]. Whether CDX2 efficiently induces formation of TSC-like cells in EpiSCs or ECCs has not been examined, but would provide new insight into the developmental potential of the various pluripotent stem cell states.

Materials and Methods

Cell culture

TSCs were maintained on MEFs in TSC medium [RPMI+20% FBS+1 μg/mL FGF4 and 1 U/mL Heparin (R&D Systems)] as described [14], unless otherwise indicated. ESC and iPSC lines were maintained on mitotically inactivated MEFs in standard ESC medium [Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) with 15% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Hyclone)] and leukemia inhibitory factor or in 2i medium [15% knockout serum replacement (KOSR; Gibco) replaced FBS, 1 μM PD0325901, and 3 μM CHIR99021 (Stemgent)]. EpiSCs were maintained on MEFs in EpiSC medium [1:1 DMEM/F12 (Gibco), 20% KOSR, 100 μM 2-mercaptoethanol, 2 mM l-glutamine (Gibco), 1 mM nonessential amino acids (Gibco), 50 μg/mL penicillin/streptomycin (Gibco), and 5 ng/mL FGF2 (R&D Systems)]. EpiSCs were split 1:4 every 2–3 days with type IV collagenase (Gibco). ECCs were maintained in DMEM with 15% FBS, l-glutamine, and penicillin/streptomycin. Linearized pCAG-Cdx2ERT2-ires-puror construct was introduced into cells, and stably transformed colonies were selected and screened as previously described [22]. The Cdx2 overexpression assay was carried out by harvesting confluent wells of pluripotent cells and seeding at a 1:100 split ratio. The next day, media were replaced with TSC medium with FGF4, Heparin, and 4-hydroxytamoxifen (Sigma) to induce transgene activity. After 6 days of CDX2ER activation, cells were passaged and maintained under standard TSC conditions for an additional two to three passages before gene expression analysis.

Reprogramming

Mouse iPS cells were generated by reprogramming as described [7]. Briefly, retroviral reprogramming vectors were produced by transfecting 293T cells with pCL-ECO and pMXs plasmid containing Oct4, Klf4, Sox2, or cMyc (OKSM) cDNAs (Addgene). OKSM tissue culture supernatant was harvested 48 h later and stored at −80°C until use. Subsequently, passage 2 E13.5 MEFs were seeded at a density of 5,000 cells/mL on gelatin in MEF culture medium (DMEM+10% FBS+200 mM glutamax+10,000 U each pen/strep) in 96-well plates. Twenty-four hours later, MEFs were cultured in OKSM supernatant for 24 h. Twenty-four hours later, OKSM supernatant was replaced with MEF medium, and then standard ESC medium on days 2 and 4, and finally ESC medium with 15% KOSR. On day 18, after retroviral treatment, iPSC colonies were picked, expanded, and characterized after passage 10. For immunofluorescent characterization, iPSCs were plated on gelatinized coverslips and grown overnight. Cells were then fixed with 4% formaldehyde, washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and incubated in 0.5% Triton X-100 in PBS for 30 min. Cells were then blocked in PBS with 10% FBS and 0.2% Triton X-100 for 1 h at room temperature, then incubated in mouse anti-SSEA-1 (MC-480; Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank) at 1:1,000 in blocking buffer overnight at 4°C. Cells were then washed with PBS and incubated with secondary antibody (Cy3-conjugated donkey anti-mouse IgM; Jackson Labs) at 1:1,000 and 1:1,000 DAPI (Sigma) in blocking buffer for 1 h. For chimera characterization, iPS cells were injected into CD1 blastocysts, which were then transferred to pseuodopregnant recipient females, whereupon they were allowed to come to term. All animal work conformed to the guidelines and regulatory standards of the University of California Santa Cruz Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Gene expression analysis

RNA was harvested from cells using Trizol (Invitrogen). cDNA was generated from 1 μg RNA using the QuantiTect Reverse Transcription Kit (Qiagen). Quantitative reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) was performed using SYBR Green and LightCycler 480 (Roche). All reactions were performed in triplicate with 100–200 ng cDNA and 300 nM primers per reaction. For each primer pair (Supplementary Table S1; Supplementary Data are available online at www.liebertpub.com/scd), a standard curve was generated to determine PCR efficiency using either R1 ESC or TSC cDNA. Relative levels of gene expression were subsequently calculated using the empirically determined efficiency.

Results

EpiSCs do not give rise to TSCs following overexpression of Cdx2 in TSC conditions

EpiSCs differ from ESCs in many ways, including developmental origin, morphology, gene expression, and developmental potential. For example, EpiSCs are thought to be capable of differentiating to trophoblast cells [5,6], while ESCs do not readily differentiate to trophoblast in the absence of transcription factor overexpression [16,30,31]. It is not yet known whether EpiSCs can give rise to TSC-like cells following overexpression of Cdx2. We therefore introduced a tamoxifen-inducible CDX2ER fusion protein [16] into R1 ESCs [32] and into EpiSCs [5] and selected multiple subclones of each cell line that were stably expressing Cdx2ER. Since Cdx2ER mRNA is constitutively expressed, but the CDX2ER protein remains inactive until 4-hydroxytamoxifen (Tx) is added [33], we were able to screen ESC and EpiSC subclones by qPCR and to select subclones expressing levels of Cdx2ER that were at least as high as the level of Cdx2 detected in TSC lines (Supplementary Fig. S1). Subsequently, we attempted to derive TSCs by treating multiple Cdx2ER-expressing ESC and EpiSC subclones with Tx in TSC medium on MEFs for 6 days (Fig. 1A, K), as previously described [16,22]. As a negative control, we treated ESC or EpiSC lines lacking the Cdx2ER plasmid with Tx in TSC medium in parallel (Fig. 1A, K). After the 6-day differentiation, cells were passaged two to three times in TSC medium without Tx, and cell morphology and gene expression were then examined to determine whether TSC-like cells had been successfully derived, using E6.5 extraembryonic ectoderm-derived TSCs [14] as a reference.

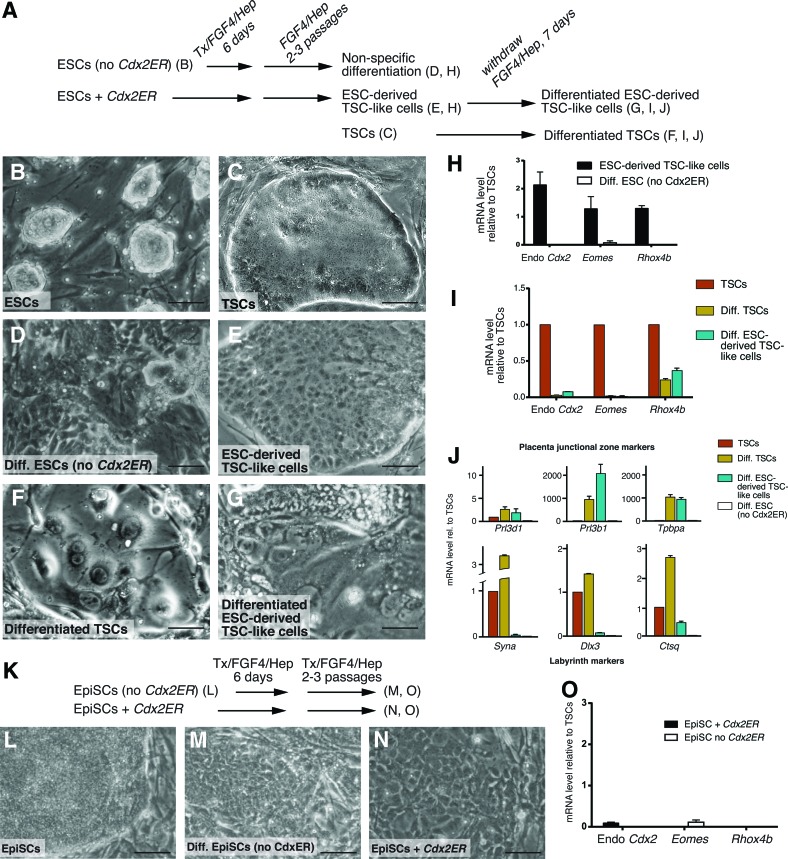

FIG. 1.

Epiblast stem cells (EpiSCs) do not give rise to trophoblast stem cells (TSCs) following Cdx2 overexpression. (A) Experimental outline of the Cdx2 overexpression assay. (B) Typical embryonic stem cell (ESC) morphology. (C) Typical morphology of TSCs in TSC medium [with fibroblast growth factor-4 (FGF4)/Heparin (Hep)]. (D) ESCs lacking Cdx2ER cultured in TSC medium do not exhibit TSC-like morphology, evidenced by ragged colony boundaries. (E) TSC-like cells derived from ESCs after Cdx2 overexpression. Note smooth colony boundary as in (C). (F) TSCs differentiated in the absence of FGF4/Hep for 7 days. (G) ESC-derived TSC-like cells differentiated in the absence of FGF4/Hep for 7 days resemble cells shown in (F). (H) Expression levels quantitative reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) of TSC markers, relative to Hprt1, in ESCs following Cdx2 overexpression and in ESCs lacking Cdx2ER, relative to TSC levels of these genes, shows that TSC-like cell lines express levels of TSC genes that are at least as high as those expressed by TSCs. (I) Expression levels of TSC markers in TSCs and ESC-derived TSC-like cells after 7-day differentiation show that both cell lines downregulate TSC markers to a similar degree. (J) Expression levels of markers of differentiated trophoblast cell types in TSCs and ESC-derived TSC-like cells after 7-day differentiation show that both cell types increase junctional zone markers to a similar degree, but only TSCs efficiently upregulate labyrinth cell markers during in vitro differentiation. (K) Experimental outline of Cdx2 overexpression in EpiSCs. (L) Typical morphology of EpiSC colonies. (M) EpiSCs lacking Cdx2 cultured in TSC medium do exhibit TSC-like morphology. (N) EpiSCs do not exhibit TSC-like morphology after Cdx2 overexpression. (O) Expression levels of TSC markers in EpiSC overexpressing Cdx2 show that EpiSCs do not acquire TSC-like properties after Cdx2 overexpression. Scale bars=150 μm, error bars=standard error among three technical replicates; Endo, endogenous. Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/scd

We first confirmed that ESCs had acquired TSC morphology after Cdx2 overexpression, as previously demonstrated [16,22]. Under conditions that support ESC self-renewal, ESCs grow as small domed colonies (Fig. 1B), while TSCs grow as flat epithelial colonies with smooth borders (Fig. 1C). Similarly, most Cdx2 overexpressing ESC subclones had acquired TSC morphology after the Cdx2 overexpression assay (5/6 subclones; Fig. 1E). By contrast, TSC morphology was not observed in ESCs cultured in TSC medium without Cdx2ER at the end of the assay (Fig. 1D), confirming that the acquisition of TSC morphology was Cdx2-dependent. Next, we evaluated expression levels of TSC markers in each of these cell lines. Endogenous Cdx2, Eomes, and Rhox4b (Ehox) are all highly expressed in TSCs and are rapidly downregulated during their differentiation [14,34]. In all of the ESC-derived TSC-like cells, TSC genes were detected at levels comparable with TSCs (5/5 subclones; Fig. 1H), indicating that the ESC-derived TSC-like cells expressed TSC markers, consistent with prior reports [16,22]. As expected, expression of TSC genes was barely detectable in differentiated ESCs lacking Cdx2ER (Fig. 1H).

Next, we confirmed that the TSC-like cells had acquired the self-renewal and differentiation properties of TSCs. Indeed, the TSC-like cells were capable of long-term self-renewal, evidenced by stable maintenance of TSC morphology for more than 50 days (10 passages) (data not shown). In addition, the TSC-like cells were able to differentiate on gelatin upon withdrawal of FGF4/Hep and MEFs, evidenced morphologically by the formation of giant and multinucleated trophoblast cell types (Fig. 1F, G), and molecularly by the downregulation of TSC genes and concomitant upregulation of genes associated with mature trophoblast, such as Prolactin family members Prl3d1 (also known as Placental Lactogen 1) and Prl3b1 (also known as Placental Lactogen 2), and Tpbpa (Trophoblast-specific protein alpha), which are expressed in placental junctional zone cell types [14,16,22,35] (Fig. 1I, J) (3/3 TSC-like lines) (Fig. 1J). We also examined expression of markers of other differentiated trophoblast cell types, such as those present in the labyrinth layer of the placenta. We noted that Syna, Dlx3, and Ctsq, which are expressed in labyrinth cell types [35–37], were expressed at higher levels in differentiated ESC-derived TSC-like cells relative to differentiated ESCs, but these genes were not upregulated to the same degree as in differentiating TSCs (Fig. 1J), suggesting that ESC-derived TSCs give rise to labyrinth cell types less efficiently in vitro than do TSCs. Importantly, differentiated trophoblast genes were not detectable in differentiated ESCs lacking Cdx2ER (Fig. 1J). These observations demonstrate that R1 ESCs reproducibly give rise to TSC-like cells, consistent with prior reports [16,22], and provide a reference for evaluating whether TSC-like cells can be derived from other pluripotent stem cell types following Cdx2 overexpression.

We next evaluated whether we could derive TSCs from EpiSCs using the assay described (Fig. 1K). Self-renewing EpiSCs grow as large, compact epithelial colonies that are morphologically similar to TSCs (Fig. 1L). However, after the Cdx2 overexpression assay, EpiSCs did not exhibit an epithelial morphology (5/5 subclones; Fig. 1N). Rather, cells lost their epithelial appearance and appeared similar to EpiSCs differentiated without Cdx2ER (Fig. 1M), pointing to nonspecific differentiation. In addition, TSC genes were not upregulated in EpiSCs after Cdx2 overexpression (Fig. 1O). Thus, TSCs cannot be derived from EpiSCs using the same conditions that are used for deriving TSCs from ESCs. We conclude that in spite of the fact that both ESCs and EpiSCs are pluripotent, the developmental potential of ESCs differs fundamentally from that of EpiSCs, evidenced by differential responsiveness to overexpressed Cdx2 in TSC culture conditions.

ECCs generate cells with TSC properties following Cdx2 overexpression

Our observations indicated that the Cdx2 overexpression assay can reveal differences in developmental potential among pluripotent stem cell lines. To determine whether other pluripotent stem cell lines differ in developmental potential, we next asked whether ECCs could give rise to TSCs. ECCs can contribute to fetal development in chimeras [38–41], suggesting that ECCs and ESCs are comparable in terms of developmental potential. To determine whether ECCs can also give rise to TSCs following Cdx2 overexpression, we introduced the Cdx2ER expression plasmid, selected subclones expressing appropriate levels of Cdx2ER (Supplementary Fig. S1), and then attempted to derive TSC-like cells as described (Fig. 2A).

FIG. 2.

Embryonal carcinoma cells (ECCs) give rise to TSC-like cells efficiently upon Cdx2 overexpression (A) Experimental outline of the Cdx2 overexpression assay. (B) Typical ECC morphology. (C) ECCs lacking Cdx2ER do not acquire TSC-like morphology. (D) TSC-like cells derived from ECCs after Cdx2 overexpression in TSC medium. (E) ECC-derived TSCs after 7 days of differentiation in the absence of FGF4/Hep. (F) Fourteen-day differentiated ECC-derived TSC-like cells (compare with Fig. 1F). (G) Expression levels of TSC markers in indicated cell line after Cdx2 overexpression show that ECC-derived TSC-like cell lines express levels of TSC genes that are at least as high as those expressed by TSCs. (H) Expression levels of TSC markers are downregulated in ECC-derived TSC-like cells during differentiation. (I) Expression levels of differentiated trophoblast genes relative to Hprt1 in indicated cell lines show that ECC-derived TSC-like cells take twice as long as TSCs to upregulate differentiation markers. Scale bars=150 μm, error bars=standard error among three technical replicates. Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/scd

We first evaluated cell morphology and gene expression in ECCs following the Cdx2 overexpression assay. Unmanipulated ECC colonies appear epithelial (Fig. 2B), and after the Cdx2 overexpression assay, ECC subclones remained epithelial (6/6 subclones; Fig. 2D), as did ECCs cultured in TSC conditions without Cdx2ER (Fig. 2C). However, TSC genes were upregulated in ECCs following the Cdx2 overexpression assay (6/6 subclones), but not in ECCs differentiated in the absence of overexpressed Cdx2 (Fig. 2G), consistent with successful derivation of TSC-like cells from ECCs. Consistent with these observations, ECC-derived TSC-like cells were capable of self-renewing for at least 10 passages.

To further characterize the TSC-like cells, we allowed them to differentiate by withdrawing FGF4/Hep and MEFs (Fig. 2A). We observed that ECC-derived TSC-like cells underwent differentiation following withdrawal of FGF4/Hep and MEFs, but the rate at which ECC-derived TSC-like cells differentiated was somewhat slower than the rate of TSC differentiation. While TSCs had completely lost their epithelial characteristics and adopted giant cell morphologies by 7 days of differentiation (Fig. 1F), giant cells were not yet visible at this time point in differentiating ECC-derived TSC-like cell cultures, and cells exhibited a loosened epithelial appearance (2/2 subclones; Fig. 2E). In addition, after 7 days of differentiation, TSC genes were downregulated, although not to the extent that they were downregulated in differentiating TSCs at this time point (Fig. 2H). Similarly, after 7 days of differentiation, markers of differentiated trophoblast were not yet fully upregulated (Fig. 2I), suggesting that ECC-derived TSC-like cells are delayed in their rate of differentiation or are resistant to differentiation. By 14 days of differentiation, ECC-derived TSC-like cells had acquired differentiated TSC morphology (2/2 subclones Fig. 2F) and upregulated markers of differentiated trophoblast, such as junctional zone and labyrinth markers (Fig. 2I). These observations indicate that ECC-derived TSC-like cells differentiate into trophoblast subtypes less efficiently than do TSCs in vitro. By contrast, trophoblast markers were not upregulated in ECCs differentiated in the absence of Cdx2ER (Fig. 2I). These observations indicate that ECCs, like ESCs, respond to Cdx2 overexpression and TSC culture conditions by generating TSC-like cells and suggest that ESCs and ECCs are equivalent in terms of developmental potential. Moreover, these observations indicate that the ability to generate TSC-like cells in response to ectopic Cdx2 is not unique to ESCs but is also a property of pluripotent cells of nonblastocyst origin.

The efficiency of deriving TSC-like cells varies among iPSC and ESC lines

Our observations indicated that the different types of pluripotent stem cells differ in their developmental potential. Given that EpiSCs and ESCs are derived from the embryo at different developmental stages, our results suggested that pluripotent stem cell origins could influence a cell line's competence to respond to TSC-inducing factors. iPSCs are thought to be very similar, if not identical to ESCs, based on gene expression and developmental potential, despite originating from more differentiated cell types [42]. We therefore hypothesized that, like ESCs, iPSCs should give rise to TSCs very robustly. To test this hypothesis, we attempted to derive TSCs from three different iPSC lines (Table 1). All three iPSC lines were first cultured beyond passage 11 in standard ESC conditions to allow these lines to stably acquire ESC gene expression profiles [43]. We then introduced the Cdx2ER expression plasmid into each iPS cell line, and then selected five to six subclones expressing levels of Cdx2ER that were at least as high as TSC levels of Cdx2 (Supplementary Fig. S1). We then attempted to derive TSC lines from each of these subclones following the Cdx2 overexpression assay (Fig. 3A).

Table 1.

Summary of Cell Lines Used in This Study

| Cell line | Cell type or reprogramming method | Origin | Reference | Genetic background |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TSC | TSC | E6.5 extraembryonic ectoderm | [14] | 129/mixed |

| ESC1 | R1 | Blastocyst | [32] | 129 |

| ESC2 | G4 | Blastocyst | [70] | 129/B6 |

| ESC3 | E14 | Blastocyst | [71] | 129/OlaHsd |

| ECC | F9 | Embryonal carcinoma | [1] | 129 |

| EpiSC | EpiSC | E5.5 epiblast | [5] | 129 |

| iPSC1 | O, K, S retrovirus | MEF | This study (Supplementary Fig. S2) | 129/B6 |

| iPSC2 | O, K, S, M piggyBac transposon | MEF | [72] | 129 |

| iPSC3 | O, K, S, M retrovirus | MEF | This study (Supplementary Fig. S2) | 129/B6 |

ECC, embryonal carcinoma cell; EpiSC, epiblast stem cell; ESC, embryonic stem cell; iPSC, induced pluripotent stem cell; K, Klf4; M, cMyc; MEF, mouse embryonic fibroblast; O, Oct4; S, Sox2; TSC, trophoblast stem cell.

FIG. 3.

Induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) and ESCs give rise to TSC-like cells with variable efficiency. (A) Experimental outline of the Cdx2 overexpression assay. (B–F) The morphology and gene expression of one representative iPSC or ESC subclone after the Cdx2 overexpression assay, showing that some iPSC/ESC lines give rise to TSC-like cells with higher efficiency than others. (G) Comparison of combined total expression values of TSC genes for all tested subclones for ESCs, EpiSCs, ECCs, and iPSCs compared with TSC values (TSC=3.0), with genetic background indicated for each cell line. Scale bar=150 μm, error bars in (B–F)=standard error among technical replicates, error bars in (G)=standard error among subclones. Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/scd

As expected, TSC-like cells could be derived from iPSC lines, although there were differences among the iPSC lines in the efficiency of derivation and the quality of the TSC-like cells. One iPSC line (iPSC2) consistently gave rise to cells with a high degree of TSC morphology and TSC-like levels of TSC gene expression (6/6 subclones; Fig. 3C). However, two iPSC lines (iPSC1 and iPSC3) gave rise to cells with relatively low degree of TSC morphology and gene expression (Fig. 3B, D) and did so with lower efficiency than other cell lines (3/5 subclones for iPSC1 and 4/5 subclones for iPSC3). We conclude that iPSCs can give rise to TSCs, although the efficiency and the quality of the resultant TSC-like cells vary among iPSC lines.

The basis for the differing capacity of the iPSC lines to give rise to TSC-like cells was unclear. While each iPSC line had been generated with different vectors or reprogramming factor cocktails (Table 1), these differences did not clearly correlate with the observed differences in propensity to form TSC-like cells. Rather, those iPSC lines that gave rise to TSC-like cells with relatively low efficiency were of mixed genetic background, while the iPSC line that gave rise to TSC-like cells efficiently was derived from mice of 129 genetic background. Since all the other pluripotent cell lines we had examined thus far were of 129 background, this prompted us to investigate whether ESCs derived from mixed backgrounds might also exhibit reduced efficiency of TSC differentiation in the Cdx2 overexpression assay, and whether the variable efficiency of producing TSC-like cells might be influenced by genetic background in ESCs and iPSCs alike.

We therefore introduced the Cdx2 overexpression plasmid into two additional ESC lines (ESC2 and ESC3), which were each of mixed genetic background (Table 1). We selected five Cdx2ER-expressing subclones from each of these two ESC lines, and then evaluated the ability of these 10 Cdx2-overexpressing subclones to give rise to TSC-like cells following the Cdx2 overexpression assay. We were able to derive cells with TSC-like morphology and gene expression from both ESC lines (5/5 subclones each), although the quality and consistency of TSC morphology and the degree of TSC gene expression (Fig. 3E, F) were lower from these ESC lines than with ESC1 (Fig. 3G). These findings are consistent with our hypothesis that the efficiency with which TSC-like cells can be derived depends upon genetic background, with 129 being the more permissive to derivation of TSC-like cells following Cdx2 overexpression.

Cdx2 overexpression induces expression of non-TSC genes in multiple pluripotent stem cell lines

Although the EpiSC line we examined was derived from a 129 background, the genetic background that we found to be permissive to derivation of TSC-like cells following Cdx2 overexpression, we were unable to derive TSCs from EpiSCs. Thus, unlike 129-derived ESC/iPSCs, 129-derived EpiSCs are not competent to respond to overexpressed Cdx2 by activating TSC gene expression, pointing to differences in developmental potential. Consistent with this proposal, EpiSCs are thought to be primed to differentiate into germ layer derivatives and express markers of the late epiblast, including Sox17, Gata6, Foxa2, and T [5,6,13,44,45]. We therefore hypothesized that the degree of lineage priming could differ between ESC/iPSCs that do not efficiently produce TSC-like cells and ESC/iPSCs that do efficiently produce TSC-like cells. To test this hypothesis, we compared expression levels of several germ layer markers in EpiSCs and in ESC/iPSC lines of differing ability to give rise to TSC-like cells (ESC1 and iPSC3), each cultured in self-renewal conditions. We observed that EpiSCs expressed higher levels of mesendoderm genes than did either the ESC or iPSC line (Fig. 4A), consistent with the lineage-primed state of EpiSCs. However, the levels of mesendoderm markers were not higher in iPSC3 than in ESC1 even though iPSC3 was refractory to forming TSC-like cells, while ESC1 was not. These observations support the hypothesis that lineage priming in EpiSCs could limit TSC potential, but lineage priming does not explain the variation in TSC potential observed among ESC/iPSC lines.

FIG. 4.

Cdx2 overexpression induces expression of non-TSC genes. (A) Mesendoderm gene expression levels in undifferentiated cell lines. (B) Germ layer marker expression levels, relative to Hprt1, in untreated EpiSCs and in five Cdx2-overexpressing subclones and control cell lines. (C) Germ layer marker expression levels, relative to Hprt1, in untreated ESC1 and iPSC3 cells and in five Cdx2-overexpressing subclones and control cells after Cdx2 overexpression for both ESC1 and iPSC3. Error bars=standard error among technical replicates. Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/scd

Given the mesendoderm-primed state of EpiSCs, we next hypothesized that Cdx2 overexpression in EpiSCs preferentially drives expression of mesendoderm genes rather than TSC genes since Cdx2 plays well-established roles in promoting mesendoderm fates in the fetus [46–49]. To test this hypothesis, we examined the expression levels of endoderm, mesoderm, and ectoderm markers, as well as Hoxb9 and Isx, which are regulated by CDX2 directly [50–52], in multiple EpiSC subclones following Cdx2 overexpression. Consistent with our predictions, we observed that ectopic Cdx2 induced the expression of the mesoderm markers, Meox1 and Hoxb9, in the majority of EpiSC subclones relative to treated and untreated parental cells (Fig. 4B). However, ectopic Cdx2 did not induce expression of Isx or other endoderm or ectoderm markers relative to treated and untreated controls. These observations are consistent with the conclusion that overexpressed Cdx2 exhibits some of its postimplantation activity in EpiSCs cultured in these conditions by activating expression of non-TSC genes.

Next, we evaluated whether ectopic Cdx2 preferentially induces expression of non-TSC genes in ESC/iPSC lines that do not efficiently give rise to TSCs. We evaluated expression of the same markers in multiple subclones of iPSC3, which did not efficiently give rise to TSCs, as well as ESC1, which did give rise efficiently to TSC-like cells. We expected to observe higher levels of non-TSC gene expression following Cdx2 overexpression in iPSC3 subclones than in ESC1 subclones. However, we were surprised to observe expression of Hoxb9 in both iPSC3 and ESC1 after 6 days of Cdx2 overexpression (Fig. 4C), suggesting that expression of non-TSC genes does not interfere with formation of TSC-like cells in ESC/iPSCs. Although we have not ruled out the possibility that TSC and non-TSC genes are expressed in distinct cells within these cultures, we note that ESC1 had given rise to TSC-like cells very efficiently. We therefore propose that genetic background limits TSC-forming efficiency in ESC/iPSCs.

Myc expression levels predict TSC-forming potential

Our evidence showed that pluripotent stem cell lines differ in their competence to respond to ectopic Cdx2, but the molecular basis for this observation was unclear. Since Oct4 expression directly limits TSC formation in ESCs [31], we hypothesized that levels of Oct4 or of other pluripotency genes might correlate inversely with TSC-forming potential. To test this hypothesis, we evaluated expression levels of Oct4 and 11 additional pluripotency genes by qPCR in seven of the pluripotent stem cell lines. We then evaluated the correlation between pluripotency gene expression value and TSC-forming ability, here defined as total TSC gene expression after Cdx2 overexpression. However, we observed no strong correlation between the Oct4 expression level and potential to give rise to TSC-like cells (Fig. 5). Similarly, we observed no strong correlation between the levels of most of the other pluripotency genes and potential to form TSC-like cells. Notably, Myc was an exception to this trend since Myc levels were inversely correlated with potential to form TSC-like cells. These observations suggest that Myc levels can predict the propensity of a given pluripotent cell line to give rise to TSC-like cells following Cdx2 overexpression with those pluripotent stem cell lines that express low levels of Myc giving rise to TSCs more efficiently. Since the level of Myc expression is lower in naïve ESCs than in the primed ESCs [9], our results suggest that naïve pluripotency is more permissive to formation of TSCs following Cdx2 overexpression than is primed pluripotency.

FIG. 5.

Correlation between TSC gene expression levels and markers of pluripotency. Average TSC gene expression values relative to Hprt1 and normalized to TSCs for all pluripotent stem cell lines used in this study (Table 1), except ESC3, which is deficient for Hprt1 [71], plotted against the average expression levels of the indicated pluripotency genes. The degree of correlation (r value) was calculated using Pearson's correlation. Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/scd

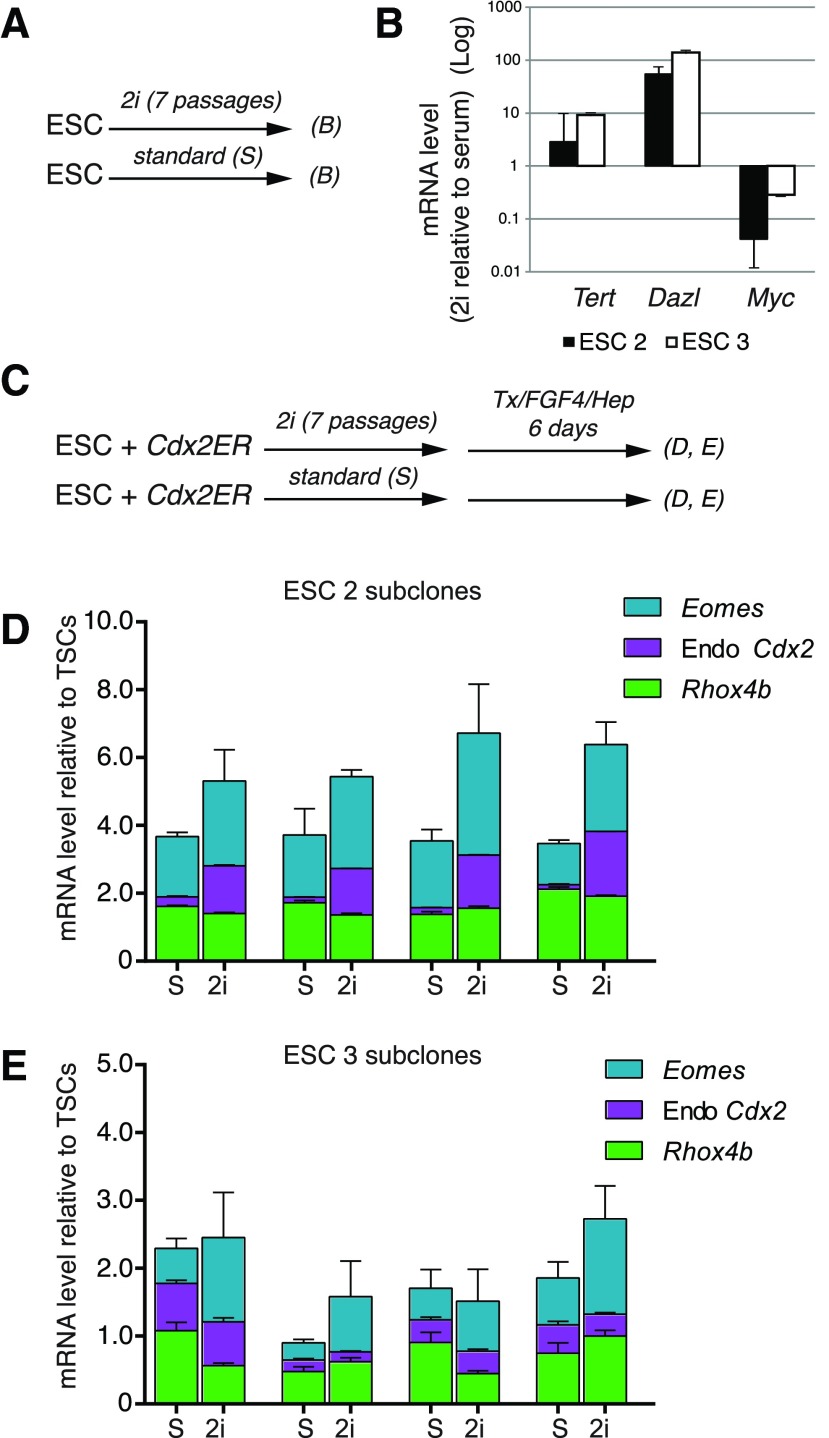

Inhibition of GSK3/MAPK signaling increase potential to form TSC-like cells

We observed that Myc expression levels in pluripotent stem cells are inversely correlated with their ability to form TSCs. Culturing ESC lines in inhibitors of GSK3 and MEK (2i) is sufficient to reduce Myc expression levels and push cells from primed to naïve pluripotent states [9,10]. We therefore hypothesized culturing ESC lines in 2i before the Cdx2 overexpression assay would increase the efficiency with which they formed TSCs. To test this hypothesis, we cultured ESC lines (ESC2 and ESC3) in 2i for seven passages (Fig. 6A), the number of passages needed to transition ESCs into the naïve pluripotent state [9]. We first confirmed that 2i treatment effectively lowered expression levels of Myc in these ESC lines (Fig. 6B). In addition, expression levels of Tert and Dazl were increased following 2i treatment, further demonstrating that the cells had entered a state of naïve pluripotency [9] (Fig. 6B). Next, we pretreated Cdx2ER-expressing ESC2 and ESC3 (four subclones each) with 2i for seven passages, and then we treated these lines with Tx and FGF4/Hep for 6 days (Fig. 6C). After this treatment, TSC-like cell morphology was again observed (not shown), and expression of markers associated with germ layer lineages was not increased (Supplementary Fig. S3), indicating that pretreatment of ESCs with 2i supports derivation of TSC-like cells. We then compared the degree to which TSC markers were upregulated in TSC-like cells derived from ESCs that had been cultured in 2i compared with TSC-like cells derived from ESCs that had been cultured in serum. We observed that TSC gene expression levels were increased in the majority of TSC-like cell lines that had been derived from ESC lines pretreated with 2i (Fig. 6D, E). These observations are consistent with the idea that naïve pluripotency is more permissive to derivation of TSC-like cells than is the primed pluripotent state.

FIG. 6.

Pretreatment of ESC lines in 2i leads to increased levels of TSC gene expression following Cdx2 overexpression. (A) Overview of the experiment shown in (B). (B) Expression levels of the ground state pluripotency markers, Tert, Dazl, and Myc, relative to Hprt1 following treatments described in (A). (C) Overview of the experiment shown in (D, E). (D, E) TSC gene expression values for ESC2 and ESC3 subclones after treatment described in (C), showing that pretreatment with 2i leads to increased expression of TSC genes following Cdx2 overexpression. Error bars=standard error among technical replicates. Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/scd

Discussion

We have shown that multiple pluripotent states can be resolved on the basis of cellular response to ectopic Cdx2, with some stem cell lines giving rise to TSC-like cells readily, and others less so. We observed that the efficiency with which pluripotent stem cell lines gave rise to TSC-like cells is influenced by their degree of naiveté. Our observations support the idea that a spectrum of pluripotent states exists, with cell lines exhibiting differing degrees of naiveté (Fig. 7). Accordingly, ectopic Cdx2 induces trophoblast with a range of efficiencies and does so more efficiently in more naïve pluripotent states. Our observations are consistent with the hypothesis that the 129 genetic background influences ESC naiveté, both in terms of expression of markers of naïve pluripotency and responsiveness to Cdx2. By contrast, ectopic Cdx2 did not induce formation of trophoblast in primed pluripotent stem cell lines, such as EpiSCs. Thus, the ability of ectopic Cdx2 to induce TSC-like cells is a newly defined property of naïve pluripotency.

FIG. 7.

Relative efficiency of TSC-like cell formation reveals a continuum of pluripotent states. In our model, there exists a continuum of pluripotent states, ranging from naïve to primed. In this study, the degree of naiveté for a given cell line is predicted by the efficiency with which it gives rise to TSC-like cells following Cdx2 overexpression. Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/scd

Our proposal that primed pluripotent cells resist forming TSC-like cells is consistent with prior observations that EpiSCs are resistant to forming XEN cells, while ESCs and iPSCs give rise to XEN cells readily [12]. Our model is also consistent with prior observations that EpiSCs are resistant to forming trophoblast following growth factor treatment [53]. Notably, multiple pluripotent states exist within EpiSCs [13,54], with some lines more primed for mesendodermal differentiation than others [13]. It would be interesting to determine whether genetic background influences the degree of naiveté and differentiation potential in EpiSCs as in ESCs, but this has not yet been examined. Rather, the degree of mesendodermal priming is thought to be influenced by the expression level of Brachyury [13]. However, we observed that ectopic Cdx2 and FGF4/Hep were sufficient to repress expression of Brachyury in EpiSCs, arguing that mesendodermal lineage priming is not a barrier to activation of trophoblast gene expression. In addition, EpiSCs were derived from the 129 background, which we found to be permissive to formation of TSC-like cells. We therefore hypothesize that EpiSCs differ in their competence to respond to ectopic Cdx2 because they represent a later developmental stage. Interestingly, EpiSCs have also been derived from mouse blastocysts [55] before the stage from which they are normally derived. Comparing the ability of ectopic Cdx2 to induce formation of TSCs between EpiSCs from pre and postimplantation embryos could provide insight into whether developmental origins or other properties limit the activity of CDX2.

Our model makes several predictions about the pluripotent state of other pluripotent stem cell lines. For example, since human ESCs bear numerous similarities to EpiSCs [5,6], our model predicts that ectopic Cdx2 would not induce expression of TSC-like cell genes in human ESCs in the conditions we tested here. Recently, totipotent or naïve pluripotent stem cell lines have been derived from both humans and mice [56–60]. In several cases, these cell lines have been shown to contribute to extraembryonic lineages in chimeras. We therefore hypothesize that totipotent human ESCs would more readily give rise to TSCs following Cdx2 overexpression, but this has not yet been tested. Interestingly, variable germ layer differentiation potential among human ESC and iPSC lines has been noted [61], but whether and how differentiation potential varies among naïve human pluripotent stem cell lines has not yet been explored. Our study thus provides a foundation for future studies to query the pluripotent state of new stem cell lines based on their response to ectopic Cdx2 and TSC medium.

Finally, our study leads to the exciting future opportunity to investigate the mechanisms that limit the trophoblast gene-inducing activity of CDX2 in primed pluripotent stem cell types. CDX2 has long been recognized to play multiple roles during embryogenesis, with a preimplantation role in promoting trophoblast fate and a postimplantation role in promoting posterior mesendoderm fates. It is tempting to speculate that a common molecular mechanism limits the trophoblast gene-inducing activity in postimplantation embryos and EpiSC lines. However, the mechanisms regulating CDX2 activity during embryogenesis are incompletely described. Exploring the mechanisms regulating CDX2 activity in naïve and primed pluripotent stem cells could lead to the discovery of how CDX2 activity is regulated in vivo. We hypothesize that transcriptional or epigenetic mechanisms could regulate CDX2 activity in naïve and primed pluripotent stem cell types. Interestingly, ESC-derived TSC-like cells fail to acquire genomic methylation features of TSCs [21], arguing that epigenetic differences between ESCs and EpiSCs could limit the developmental potential of EpiSCs to become TSCs. Differences in the transcriptomes, proteomes, and chromatin states of ESCs and EpiSCs have been compared [62–65]. Notably, NuRD-dependent methylation prevents ESCs from spontaneously acquiring trophoblast fate [66–69]. However, it is not known whether NuRD methylation maintains this lineage barrier in EpiSCs. Use of conditional alleles to study loss of gene function in EpiSCs will provide exciting insight into molecular mechanisms preventing EpiSCs from differentiating to TSCs and regulating CDX2 activity during postimplantation stages of development.

In summary, we have compared the relative efficiency with which TSC-like cells can be derived from a variety of pluripotent stem cell types. Our data show that TSC-like cells can be derived efficiently from naïve pluripotent stem cell lines, but not from primed pluripotent stem cell lines. We also report that ESC lines derived from mixed genetic background exhibit features of primed ESCs, but when these ESCs are pushed to naïve pluripotency using inhibitors of MEK/GSK3, these cell lines exhibit increased efficiency of TSC-like cell derivation. We propose that the Cdx2 overexpression assay could be used to assess the pluripotent state of newly derived mouse, and possibly human, stem cell lines.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. Jonathan S. Draper and members of the Ralston Laboratory for discussions and Dr. Paul Tesar and Dr. Knut Woltjen for the cell lines. S.B. was supported by NIH T32 GM008646 and A.P. was supported by CIRM TG2-01157. This study was supported by the UCSC Committee on Research, Ellison Medical Foundation, and NIH R01GM104009 grants to A.R.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Kahan BW. and Ephrussi B. (1970). Developmental potentialities of clonal in-vitro cultures of mouse testicular teratoma. J Natl Cancer Inst 44:1015–1036 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Evans MJ. and Kaufman MH. (1981). Establishment in culture of pluripotential cells from mouse embryos. Nature 292:154–156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thomson JA, Itskovitz-Eldor J, Shapiro SS, Waknitz MA, Swiergiel JJ, Marshall VS. and Jones JM. (1998). Embryonic stem cell lines derived from human blastocysts. Science 282:1145–1147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Martin GR. (1981). Isolation of a pluripotent cell-line from early mouse embryos cultured in medium conditioned by teratocarcinoma stem-cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 78:7634–7638 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tesar PJ, Chenoweth JG, Brook FA, Davies TJ, Evans EP, Mack DL, Gardner RL. and McKay RDG. (2007). New cell lines from mouse epiblast share defining features with human embryonic stem cells. Nature 448:196–199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brons IGM, Smithers LE, Trotter MWB, Rugg-Gunn P, Sun BW, Lopes S, Howlett SK, Clarkson A, Ahrlund-Richter L, Pedersen RA. and Vallier L. (2007). Derivation of pluripotent epiblast stem cells from mammalian embryos. Nature 448:191–195 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Takahashi K. and Yamanaka S. (2006). Induction of pluripotent stem cells from mouse embryonic and adult fibroblast cultures by defined factors. Cell 126:663–676 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ohtsuka S. and Dalton S. (2008). Molecular and biological properties of pluripotent embryonic stem cells. Gene Ther 15:74–81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Marks H, Kalkan T, Menafra R, Denissov S, Jones K, Hofemeister H, Nichols J, Kranz A, Stewart AF, Smith A. and Stunnenberg HG. (2012). The transcriptional and epigenomic foundations of ground state pluripotency. Cell 149: 590–604 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ying QL, Wray J, Nichols J, Batlle-Morera L, Doble B, Woodgett J, Cohen P. and Smith A. (2008). The ground state of embryonic stem cell self-renewal. Nature 453:519–523 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nichols J. and Smith A. (2009). Naive and primed pluripotent states. Cell Stem Cell 4:487–492 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cho LT, Wamaitha SE, Tsai IJ, Artus J, Sherwood RI, Pedersen RA, Hadjantonakis AK. and Niakan KK. (2012). Conversion from mouse embryonic to extra-embryonic endoderm stem cells reveals distinct differentiation capacities of pluripotent stem cell states. Development 139:2866–2877 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bernemann C, Greber B, Ko K, Sterneckert J, Han DW, Araúzo-Bravo MJ. and Schöler HR. (2011). Distinct developmental ground states of epiblast stem cell lines determine different pluripotency features. Stem Cells 29:1496–1503 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tanaka S, Kunath T, Hadjantonakis AK, Nagy A. and Rossant J. (1998). Promotion of trophoblast stem cell proliferation by FGF4. Science 282:2072–2075 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kunath T, Arnaud D, Uy G, Okamoto I, Chureau C, Yamanaka Y, Heard E, Gardner R, Avner P. and Rossant J. (2005). Imprinted X-inactivation in extra-embryonic endoderm cell lines from mouse blastocysts. Development 132:1649–1661 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Niwa H, Toyooka T, Shimosato D, Strumpf D, Takahashi K, Yagi R. and Rossant J. (2005). Interaction between Oct3/4 and Cdx2 determines trophectoderm differentiation. Cell 123:917–929 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schenke-Layland K, Angelis E, Rhodes KE, Heydarkhan-Hagvall S, Mikkola HK. and Maclellan WR. (2007). Collagen IV induces trophoectoderm differentiation of mouse embryonic stem cells. Stem Cells 25:1529–1538 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.He S, Pant D, Schiffmacher A, Meece A. and Keefer CL. (2008). Lymphoid enhancer factor 1-mediated Wnt signaling promotes the initiation of trophoblast lineage differentiation in mouse embryonic stem cells. Stem Cells 26:842–849 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nishioka N, Inoue K, Adachi K, Kiyonari H, Ota M, Ralston A, Yabuta N, Hirahara S, Stephenson RO, et al. (2009). The Hippo signaling pathway components Lats and Yap pattern Tead4 activity to distinguish mouse trophectoderm from inner cell mass. Dev Cell 16:398–410 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lu CW, Yabuuchi A, Chen L, Viswanathan S, Kim K. and Daley GQ. (2008). Ras-MAPK signaling promotes trophectoderm formation from embryonic stem cells and mouse embryos. Nat Genet 40:921–926 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cambuli F, Murray A, Dean W, Dudzinska D, Krueger F, Andrews S, Senner CE, Cook SJ. and Hemberger M. (2014). Epigenetic memory of the first cell fate decision prevents complete ES cell reprogramming into trophoblast. Nat Commun 5:5538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ralston A, Cox BJ, Nishioka N, Sasaki H, Chea E, Rugg-Gunn P, Guo GJ, Robson P, Draper JS. and Rossant J. (2010). Gata3 regulates trophoblast development downstream of Tead4 and in parallel to Cdx2. Development 137:395–403 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nishiyama A, Xin L, Sharov A, Thomas M, Mowrer G, Meyers E, Piao Y, Mehta S, Yee S, et al. (2009). Uncovering early response of gene regulatory networks in ESCs by systematic induction of transcription factors. Cell Stem Cell 5:420–433 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kuckenberg P, Peitz M, Kubaczka C, Becker A, Egert A, Wardelmann E, Zimmer A, Brüstle O. and Schorle H. (2011). Lineage conversion of murine extraembryonic trophoblast stem cells to pluripotent stem cells. Mol Cell Biol 31:1748–1756 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wu T, Wang H, He J, Kang L, Jiang Y, Liu J, Zhang Y, Kou Z, Liu L, Zhang X. and Gao S. (2011). Reprogramming of trophoblast stem cells into pluripotent stem cells by Oct4. Stem Cells 29:755–763 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Niakan KK, Ji H, Maehr R, Vokes SA, Rodolfa KT, Sherwood RI, Yamaki M, Dimos JT, Chen AE, et al. (2010). Sox17 promotes differentiation in mouse embryonic stem cells by directly regulating extraembryonic gene expression and indirectly antagonizing self-renewal. Genes Dev 24:312–326 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shimosato D, Shiki M. and Niwa H. (2007). Extra-embryonic endoderm cells derived from ES cells induced by GATA factors acquire the character of XEN cells. BMC Dev Biol 7:80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Niakan KK, Schrode N, Cho LT. and Hadjantonakis AK. (2013). Derivation of extraembryonic endoderm stem (XEN) cells from mouse embryos and embryonic stem cells. Nat Protoc 8:1028–1041 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schroeder IS, Sulzbacher S, Nolden T, Fuchs J, Czarnota J, Meisterfeld R, Himmelbauer H. and Wobus AM. (2012). Induction and selection of Sox17-expressing endoderm cells generated from murine embryonic stem cells. Cells Tissues Organs 195:507–523 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Beddington RS. and Robertson EJ. (1989). An assessment of the developmental potential of embryonic stem cells in the midgestation mouse embryo. Development 105:733–737 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Niwa H, Miyazaki J. and Smith A. (2000). Quantitative expression of Oct-3/4 defines differentiation, dedifferentiation or self-renewal of ES cells. Nat Genet 24:372–376 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nagy A, Rossant J, Nagy R, Abramow-Newerly W. and Roder JC. (1993). Derivation of completely cell culture-derived mice from early-passage embryonic stem cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 90:8424–8428 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Eilers M, Picard D, Yamamoto KR. and Bishop JM. (1989). Chimeras of myc oncoprotein and steroid-receptors cause hormone-dependent transformation of cells. Nature 340:66–68 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jackson M, Baird JW, Nichols J, Wilkie R, Ansell JD, Graham G. and Forrester LM. (2003). Expression of a novel homeobox gene Ehox in trophoblast stem cells and pharyngeal pouch endoderm. Dev Dyn 228:740–744 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Simmons DG, Fortier AL. and Cross JC. (2007). Diverse subtypes and developmental origins of trophoblast giant cells in the mouse placenta. Dev Biol 304:567–578 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Simmons DG, Natale DR, Begay V, Hughes M, Leutz A. and Cross JC. (2008). Early patterning of the chorion leads to the trilaminar trophoblast cell structure in the placental labyrinth. Development 135:2083–2091 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Morasso MI, Grinberg A, Robinson G, Sargent TD. and Mahon KA. (1999). Placental failure in mice lacking the homeobox gene Dlx3. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 96:162–167 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mintz B. and Illmensee K. (1975). Normal genetically mosaic mice produced from malignant teratocarcinoma cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 72:3585–3589 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Papaioannou VE, McBurney MW, Gardner RL. and Evans MJ. (1975). Fate of teratocarcinoma cells injected into early mouse embryos. Nature 258:70–73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Andrews PW. (2002). From teratocarcinomas to embryonic stem cells. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 357:405–417 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Blelloch RH, Hochedlinger K, Yamada Y, Brennan C, Kim MJ, Mintz B, Chin L. and Jaenisch R. (2004). Nuclear cloning of embryonal carcinoma cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 101:13985–13990 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yamanaka S. (2012). Induced pluripotent stem cells: past, present, and future. Cell Stem Cell 10:678–684 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Polo JM, Liu S, Figueroa ME, Kulalert W, Eminli S, Tan KY, Apostolou E, Stadtfeld M, Li YS, et al. (2010). Cell type of origin influences the molecular and functional properties of mouse induced pluripotent stem cells. Nat Biotechnol 28:848–855 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tsakiridis A, Huang Y, Blin G, Skylaki S, Wymeersch F, Osorno R, Economou C, Karagianni E, Zhao S, Lowell S. and Wilson V. (2014). Distinct Wnt-driven primitive streak-like populations reflect in vivo lineage precursors. Development 141:1209–1221 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kojima Y, Kaufman-Francis K, Studdert JB, Steiner KA, Power MD, Loebel DA, Jones V, Hor A, de Alencastro G, et al. (2014). The transcriptional and functional properties of mouse epiblast stem cells resemble the anterior primitive streak. Cell Stem Cell 14:107–120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chawengsaksophak K, de Graaff W, Rossant J, Deschamps J. and Beck F. (2004). Cdx2 is essential for axial elongation in mouse development. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 101:7641–7645 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chawengsaksophak K, James R, Hammond VE, Köntgen F. and Beck F. (1997). Homeosis and intestinal tumours in Cdx2 mutant mice. Nature 386:84–87 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Beck F, Chawengsaksophak K, Luckett J, Giblett S, Tucci J, Brown J, Poulsom R, Jeffery R. and Wright NA. (2003). A study of regional gut endoderm potency by analysis of Cdx2 null mutant chimaeric mice. Dev Biol 255:399–406 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Guo RJ, Suh ER. and Lynch JP. (2004). The role of Cdx proteins in intestinal development and cancer. Cancer Biol Ther 3:593–601 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.van den Akker E, Forlani S, Chawengsaksophak K, de Graaff W, Beck F, Meyer BI. and Deschamps J. (2002). Cdx1 and Cdx2 have overlapping functions in anteroposterior patterning and posterior axis elongation. Development 129:2181–2193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Choi MY, Romer AI, Hu M, Lepourcelet M, Mechoor A, Yesilaltay A, Krieger M, Gray PA. and Shivdasani RA. (2006). A dynamic expression survey identifies transcription factors relevant in mouse digestive tract development. Development 133:4119–4129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Boyd M, Hansen M, Jensen TGK, Perearnau A, Olsen AK, Bram LL, Bak M, Tommerup N, Olsen J. and Troelsen JT. (2010). Genome-wide analysis of CDX2 binding in intestinal epithelial cells (Caco-2). J Biol Chem 285:25115–25125 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bernardo AS, Faial T, Gardner L, Niakan KK, Ortmann D, Senner CE, Callery EM, Trotter MW, Hemberger M, et al. (2011). BRACHYURY and CDX2 mediate BMP-induced differentiation of human and mouse pluripotent stem cells into embryonic and extraembryonic lineages. Cell Stem Cell 9:144–155 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Han DW, Tapia N, Joo JY, Greber B, Araúzo-Bravo MJ, Bernemann C, Ko K, Wu G, Stehling M, Do JT. and Schöler HR. (2010). Epiblast stem cell subpopulations represent mouse embryos of distinct pregastrulation stages. Cell 143:617–627 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Najm FJ, Chenoweth JG, Anderson PD, Nadeau JH, Redline RW, McKay RD. and Tesar PJ. (2011). Isolation of epiblast stem cells from preimplantation mouse embryos. Cell Stem Cell 8:318–325 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Gafni O, Weinberger L, Mansour AA, Manor YS, Chomsky E, Ben-Yosef D, Kalma Y, Viukov S, Maza I, et al. (2013). Derivation of novel human ground state naive pluripotent stem cells. Nature 504:282–286 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Macfarlan TS, Gifford WD, Driscoll S, Lettieri K, Rowe HM, Bonanomi D, Firth A, Singer O, Trono D. and Pfaff SL. (2012). Embryonic stem cell potency fluctuates with endogenous retrovirus activity. Nature 487:57–63 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Morgani SM, Canham MA, Nichols J, Sharov AA, Migueles RP, Ko MS. and Brickman JM. (2013). Totipotent embryonic stem cells arise in ground-state culture conditions. Cell Rep 3:1945–1957 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ware CB, Nelson AM, Mecham B, Hesson J, Zhou W, Jonlin EC, Jimenez-Caliani AJ, Deng X, et al. (2014). Derivation of naive human embryonic stem cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 111:4484–4489 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hanna J, Cheng AW, Saha K, Kim J, Lengner CJ, Soldner F, Cassady JP, Muffat J, Carey BW. and Jaenisch R. (2010). Human embryonic stem cells with biological and epigenetic characteristics similar to those of mouse ESCs. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 107:9222–9227 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Bock C, Kiskinis E, Verstappen G, Gu H, Boulting G, Smith ZD, Ziller M, Croft GF, Amoroso MW, et al. (2011). Reference maps of human ES and iPS cell variation enable high-throughput characterization of pluripotent cell lines. Cell 144:439–452 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Senner CE, Krueger F, Oxley D, Andrews S. and Hemberger M. (2012). DNA methylation profiles define stem cell identity and reveal a tight embryonic-extraembryonic lineage boundary. Stem Cells 30:2732–2745 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Fröhlich T, Kösters M, Graf A, Wolf E, Kobolak J, Brochard V, Dinnyés A, Jouneau A. and Arnold GJ. (2013). iTRAQ proteome analysis reflects a progressed differentiation state of epiblast derived versus inner cell mass derived murine embryonic stem cells. J Proteomics 90:38–51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Song J, Saha S, Gokulrangan G, Tesar PJ. and Ewing RM. (2012). DNA and chromatin modification networks distinguish stem cell pluripotent ground states. Mol Cell Proteomics 11:1036–1047 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Hutchins AP, Choo SH, Mistri TK, Rahmani M, Woon CT, Ng CK, Jauch R. and Robson P. (2013). Co-motif discovery identifies an Esrrb-Sox2-DNA ternary complex as a mediator of transcriptional differences between mouse embryonic and epiblast stem cells. Stem Cells 31:269–281 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Latos PA, Helliwell C, Mosaku O, Dudzinska DA, Stubbs B, Berdasco M, Esteller M. and Hendrich B. (2012). NuRD-dependent DNA methylation prevents ES cells from accessing a trophectoderm fate. Biol Open 1:341–352 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Zhu D, Fang J, Li Y. and Zhang J. (2009). Mbd3, a component of NuRD/Mi-2 complex, helps maintain pluripotency of mouse embryonic stem cells by repressing trophectoderm differentiation. PLoS One 4:e7684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kaji K, Nichols J. and Hendrich B. (2007). Mbd3, a component of the NuRD co-repressor complex, is required for development of pluripotent cells. Development 134:1123–1132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kaji K, Caballero IM, MacLeod R, Nichols J, Wilson VA. and Hendrich B. (2006). The NuRD component Mbd3 is required for pluripotency of embryonic stem cells. Nat Cell Biol 8:285–292 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Papadaki C, Alexiou M, Cecena G, Verykokakis M, Bilitou A, Cross JC, Oshima RG. and Mavrothalassitis G. (2007). Transcriptional repressor Erf determines extraembryonic ectoderm differentiation. Mol Cell Biol 27:5201–5213 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Hooper M, Hardy K, Handyside A, Hunter S. and Monk M. (1987). HPRT-deficient (Lesch-Nyhan) mouse embryos derived from germline colonization by cultured-cells. Nature 326:292–295 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Woltjen K, Michael IP, Mohseni P, Desai R, Mileikovsky M, Hamalainen R, Cowling R, Wang W, Liu PT, et al. (2009). piggyBac transposition reprograms fibroblasts to induced pluripotent stem cells. Nature 458:766–770 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.