Abstract

Objective

Many adolescents engage in polydrug use; however, little is known about whether alcohol and other drug problems show similar posttreatment trajectories of change. We examined concurrent patterns of change for Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition, symptoms related to the use of alcohol, marijuana, and other drugs and identified predictors of the most common cross-drug patterns of change.

Method

Adolescents (N = 542) recruited from addictions treatment were assessed at baseline and at 1-and 3-year follow-up. Latent class mixture modeling identified trajectories for alcohol, marijuana, and other-drug symptoms. Latent class analysis identified cross-drug patterns of change and was used to examine conduct disorder and depression as predictors of cross-drug patterns of change.

Results

For alcohol users, three improving groups (72%), stable-low (19%) and stable-high (6%) groups, and groups with increasing trajectories (3%) were identified. For marijuana users, an asymptomatic class (23%), two improving classes (46%), stable-low (13%) and stable-high (13%) classes, and a class with an increasing trajectory (4%) were found. For users of other drugs, groups with asymptomatic (57%), improving (20%), increasing (12%), and stable-high (11%) trajectories were identified. Latent class analysis of cross-drug patterns of change identified three subtypes representing generally concordant cross-drug patterns of change and one subtype that involved stable-high marijuana problems, decreasing alcohol problems, and increasing other-drug problems. Conduct disorder was associated with greater persistence of substance problems.

Conclusions

The majority of treated adolescents had similar cross-drug patterns of change for alcohol, marijuana, and other drugs; however, exceptions exist. Furthermore, adolescents with co-occurring psychopathology may benefit from continuing intervention, because they tend to report more persistent posttreatment substance-related problems.

A DOLESCENTS SHOW DIVERSE PATTERNS of change following addictions treatment, typically represented by stable-low, stable-high, improving, or worsening trajectories of substance involvement. Most published studies of treated adolescents have reported short-term follow-up data (e.g., 1 year; see Chung and Maisto, 2006, and Williams et al., 2000, for reviews). Only recently have longer-term follow-up data on treated adolescents become available (e.g., Chung et al., 2003; Tapert et al., 2003). In addition, most research on clinical course in treated adolescents has reported on outcomes for only one substance (e.g., alcohol) or reported a combined; substance-use outcome (i.e., any alcohol or other-drug use). Because many treated adolescents are polydrug users, however (Hser et al., 2001; Martin et al., 1996), there is a crucial need to understand the extent to which treatment may differentially impact adolescents’ involvement with the most commonly used substances, alcohol and marijuana, to improve the effectiveness of substance-use interventions offered to youths.

Many adolescents entering addictions treatment have more than one substance-use disorder (SUD), most often owing to alcohol and marijuana use (Winters et al., 1999). The effect of polysubstance use on treatment outcomes is particularly evident during early recovery. Specifically, initial relapse episodes involving multiple substances (23% of initial relapses) have been associated with a more rapid return to problem use (Brown et al., 2000). The potentially negative impact of polysubstance use on outcomes highlights the importance of understanding how changes in the use of one substance may affect the use of another. For example, some youths may substitute the use of one drug for another, temporarily consuming alcohol instead of marijuana to avoid positive urine drug screens. Alternatively, a return to alcohol or marijuana use may influence an adolescent’s motivation to refrain from other-drug use. Little is known about drug-substitution effects or potential synergistic effects of polydrug use on the longer-term course of substance-related problems, although such information could guide efforts to improve treatment.

Studies that have identified prototypical trajectories of substance use in treated adolescents have focused typically on either a single substance such as alcohol (e.g., Brown et al., 2001; Chung et al., 2003) or marijuana (Waldron et al., 2005) or examined substance involvement across alcohol and other drugs more generally (e.g., Godley et al., 2004). Few studies have examined the extent to which treatedadolescents’ use of alcohol and other drugs shows similar or distinct posttreatment patterns of change. In one study of treated youths, a moderate degree of agreement between the trajectories for alcohol and other drugs over 1-year follow-up was found, suggesting that levels of abstinence from alcohol and other drugs tended to increase or decline together (Chung et al., 2004). Exceptions occurred, however, with some youths showing, for example, increases in abstinence from alcohol but decreasing or low abstinence from other drugs over short-term follow-up. Further research is needed on longer-term outcomes in treated adolescents and to examine the extent to which involvement with alcohol, marijuana, and other drugs shows similar or distinct post-treatment patterns of change.

In addition to characterizing posttreatment patterns of change in substance use in adolescents, research has examined demographic and psychiatric predictors of trajectory types. Among demographic features, a relatively consistent finding is that treated males are more likely to be in stable-high or persistent alcohol-use trajectories, compared with females (e.g., Chung et al., 2004; Tapert et al., 2003), whereas treated females are more likely to be in trajectories representing lower levels of substance use (e.g., Godley et al., 2004). Psychopathology, such as depression and conduct disorder, which may precede and predict chronicity of substance-related problems, has not consistently predicted trajectory types. In some studies, conduct disorder was associated with stable-high levels of substance use (e.g., Godley et al., 2004), whereas another study found no association when conduct-disorder symptoms did not include behaviors related to substance use (Tapert et al., 2003). Likewise, depression was associated with trajectories of continuing substance use in one study (Godley et al., 2004) but showed no association with alcohol-problem trajectories in another (Chung et al., 2004).

Increased understanding of concurrent patterns of change across specific substances, as well as predictors of distinct trajectory types, can help to clarify the extent to which the use of different substances reflects common or distinct underlying processes of change. This study used dual trajectory analysis (Nagin and Tremblay, 2001) to characterize the extent to which alcohol, marijuana, and other-drug-related problems show concordant patterns of change over 3-year follow-up. Based on short-term study results (Chung et al., 2004), we predicted that alcohol and marijuana would show concordant patterns of change over time (rather than drug-substitution effects, in which the use of one substance increases while the use of another decreases) and that continuing problems with other drugs would be more likely in the context of continuing alcohol or marijuana symptoms. We also hypothesized, based on previous research (e.g., Godley et al., 2004), that males would be more likely to be in stable-high trajectories, whereas females would be more likely to be in stable-low and improving trajectories. With regard to co-occurring psychopathology, which can negatively impact an adolescent’s efforts to reduce substance use, we predicted that conduct disorder and depression would be associated with trajectories representing continuing substance-related problems.

Method

Participants

This study included 542 adolescents (ages 12-19) recruited from addictions treatment to participate in a longitudinal study on substance-use behavior involving baseline (shortly after treatment admission) and 1- and 3-year follow-up assessments (Chung et al., 2003). The majority of participants were male (58.9%) and white (80.1%). The sample included some representation of black (19.2%) and other ethnic groups (0.7%). Approximately half (52.7%) of the participants were recruited from inpatient or residential settings; 47.3% were recruited from outpatient settings. There were no significant differences across sites in participants’ age, gender, or ethnicity. Participants were, on average (SD), 16.4 (1.4) years old at baseline and represented a wide range of socioeconomic status (range: 1-5 [1 = high socioeconomic status]; mean = 3.0 [1.1]; Hollingshead, 1975).

At baseline, a majority had a lifetime Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM-IV; American Psychiatric Association, 1994) alcohol diagnosis (73.2%; 13.5% abuse, 59.7% dependence), and a majority had a lifetime marijuana diagnosis (68.1%; 16.2% abuse, 51.9% dependence). More than half had both lifetime DSM-IV alcohol and marijuana diagnoses at baseline (59.2%), with smaller proportions meeting criteria only for an alcohol diagnosis (14%) or a marijuana diagnosis (8.7%). Almost one of every three adolescents (30.4%) met criteria for a lifetime SUD for one or more of the following five substances: hallucinogens, cocaine, opioids, sedatives, and amphetamines. Across these five substances, the average number of substances for which an adolescent met criteria for a lifetime SUD was 0.5 (0.9; range: 0-5). Among these five “other drugs,” adolescents most often met criteria for an SUD diagnosis because of the use of hallucinogens (17.5%) and cocaine (10.9%). A minority (15.7%) met SUD criteria at baseline for alcohol, marijuana, and at least one of the five other drugs. With regard to lifetime psychopathology at baseline, 68% met criteria for conduct disorder, and 52% met criteria for a depression diagnosis (i.e., major depression or dysthymia).

Recruitment procedure

From 1990 to 2000, adolescents were recruited from 14 addictions treatment sites in western Pennsylvania. All treatment sites adhered to an outcome goal of abstinence from alcohol and other nonprescribed drugs. Treatment protocols varied across sites but typically included group, family, and individual therapy components. During a visit to a treatment program, study personnel provided adolescents with information about the project. Teens interested in study participation completed a “consent to contact form.” Among those who provided consent to contact, 77% completed a telephone screen and the baseline assessment. The remaining teens (23%) were ineligible following screening or did not complete the phone screen or baseline assessment. Among adolescents who provided consent to contact, teens who completed the baseline assessment did not differ in demographic characteristics from those who did not.

Study procedure

Written informed consent or assent was obtained before each assessment from all participants and from a legal guardian for minors. All assessments were completed at research project offices. At baseline, the participants reported on their lifetime history of substance use, substance-related problems, and co-occurring psychopathology. At 1- and 3-year follow-ups, data on substance-related problems covering the interval since the last assessment were collected. Teens received gift certificates for study participation: $125 for the baseline assessment, $100 for the 1-year follow-up, and $125 for the 3-year follow-up. The university’s institutional review board approved the research protocol.

Measures

DSM-IV substance-use disorder diagnoses and symptoms

An adapted version of the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV SUDs (SCID; First et al., 1997; Martin et al., 1995) was used to determine the presence of SUD diagnoses and symptom counts. Adaptations to the SCID were made to accommodate developmental considerations in symptom assessment. The adaptations included providing examples of youth-relevant symptoms (e.g., school grades dropping because of substance use) and suggestions for follow-up probes to aid determination of the clinical significance of a symptom. For each symptom rated as clinically present, ages of onset and offset were obtained to the nearest month. Symptom onset and offset data were used to determine whether a symptom was present during a specific interval (e.g., the year before baseline). The adapted SCID demonstrated moderate-to-high interrater reliability for symptom ratings and ages of symptom onset and offset, as well as good concurrent validity in adolescents (Martin et al., 1995; 2000).

Co-occurring psychopathology

Participants completed the adolescent version of the Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia (K-SADS; Clark et al., 1997; Kaufman et al., 1997) to assess lifetime occurrence of other DSM-IV Axis I psychopathology (e.g., conduct disorder, major depression) at baseline. The K-SADS demonstrated good interrater reliability (Clark et al., 1997).

Statistical analyses

The SAS Proc Traj (Jones et al., 2001) was used to identify more homogeneous latent trajectory classes based on longitudinal data through 3-year follow-up. The program can accommodate both missing data and unequal temporal spacing of assessments (Nagin, 1999). Trajectory analyses were first conducted separately for alcohol, marijuana, and other drugs. Trajectories were identified based on past-year DSM-IV abuse and dependence symptom count (a total of 11 symptoms for each substance, except for cannabis and hallucinogens, which had a total of 10 symptoms for each) at baseline and 1, 2, and 3 years after baseline. The 3-year follow-up, which typically covered the 2-year interval since the 1-year follow-up, provided past-year symptom-count data for the 2-year and 3-year time points. Because ages of symptom onset and offset were collected to the nearest month, we were able to determine the presence of a symptom during a specified interval (e.g., the past year), using age at baseline as the reference point.

For the other-drug analyses, the sum of DSM-IV abuse and dependence symptoms across five “other drug” classes (i.e., hallucinogens, cocaine, opioids, stimulants, sedatives) was used. Because of the wide range in the other-drug symptom count (baseline: 0-33, 1 year: 0-16, 2 year: 0-22, 3 year: 0-28), a square root transformation was applied to normalize the distribution, and this result was then multiplied by 2 so that the range of values (i.e., 0-11.5) was similar to that for alcohol and marijuana (with maximum symptom counts of 11 and 10, respectively).

Trajectory analyses for alcohol, marijuana, and other drugs tested models specifying data with a censored normal distribution, two to eight groups, and a quadratic function as the highest-order polynomial to estimate trajectory shape for alcohol, marijuana, and other drugs. The best-fitting model was determined by considering the Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC; values closer to 0 indicate better fit); classification quality (i.e., average conditional probability of being assigned to the most likely class = .80), and the distribution of cases across classes.

After selecting the best-fitting model for a substance, dual trajectory analyses generated joint probabilities of class membership for pairs of drug types (i.e., alcohol and marijuana, alcohol and other drugs, marijuana and other drugs). Joint probability estimates characterize the linkage between changes in symptom status for each pair of substances, which can provide information on the extent to which the linked behaviors represent manifestations of a common or distinct underlying process of change (Nagin and Tremblay, 2001).

To examine associated features of trajectories across alcohol, marijuana, and other drugs simultaneously (rather than just pair-wise analyses), we identified the most common patterns of co-occurring trajectories (i.e., “subtypes” or latent classes of trajectories for alcohol, marijuana, and other drugs) using Latent Gold Version 3.0 (Vermunt and Magidson, 2003). Models tested two to eight classes. Model selection was based on consideration of the BIC, the classification quality, and the pattern of cross-drug trajectories represented by the classes. An advantage of this subtyping method includes simultaneous estimation of cross-drug sub-types and their association with covariates (e.g., demographic characteristics, conduct disorder, depression), while taking into account the probabilistic assignment of cases to specific subtypes.

Results

Mean symptom count over follow-up: Alcohol, marijuana, other drugs

Alcohol and marijuana showed a similar level of severity and similar patterns of change over 3-year follow-up. For both substances, severity decreased from baseline to 1 year, with reductions maintained through 3-year follow-up. For alcohol, the mean symptom count was 3.3 (3.1) at baseline; 1.7 (2.3) at 1 year; 2.0 (2.4) at 2 years; and 1.8 (2.4) at 3 years. For marijuana, the mean symptom count was 3.5 (3.2) at baseline; 2.1 (2.5) at 1 year; 2.4 (2.7) at 2 years; and 2.0 (2.5) at 3 years. For other drugs, the overall severity was lower, compared with that for alcohol and marijuana. Although there was a reduction in the mean symptom count from baseline (untransformed mean = 1.8 [4.0]) to 1 year (0.8 [2.3]), gains were not maintained, on average, through 2 years (untransformed mean = 1.2 [3.0]) and 3 years (untransformed mean = 1.5 [3.7]).

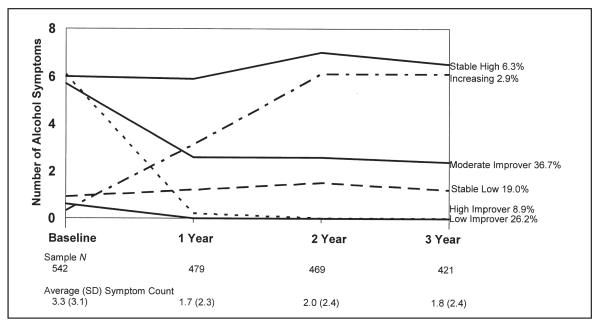

Alcohol trajectories

Among the two to eight class models tested, a six-class solution provided the best-fitting model with good distribution of cases across classes (BIC = -3,523.74; Figure 1). The next best-fitting model was the five-class solution (BIC = -3,526.86). In the six-class model, three improving groups were identified: high improver (8.9%, decrease from an average of 6.1 to 0 symptoms), moderate improver (36.7%, decrease from an average of 5.7 to 2.4 symptoms), and low improver (26.2%, decrease from an average of 0.6 to 0 symptoms). A minority showed a stable-high symptom trajectory (6.3%, average of roughly 6.0 symptoms) or a stable-low alcohol-symptom trajectory (19.0%, average of roughly 1.0 symptoms). A small proportion showed an increase in symptoms (2.9%) over follow-up. Improving classes constituted the majority of the sample (72%), although initial symptom severity and average magnitude of improvement differed across the improving classes.

Figure 1.

Alcohol symptom trajectories

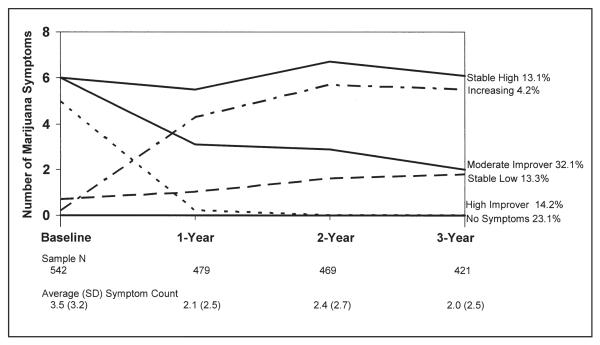

Marijuana trajectories

Similar to alcohol, a six-class solution was selected for marijuana as providing the best-fitting model with good distribution of cases across classes (BIC = -3,434.75; Figure 2). Although the seven-class solution had the best BIC (-3,429.79), this solution included a low-prevalence class that resulted in nonconvergence of the model in dual trajectory analyses. In contrast to alcohol, the six-class marijuana solution included a group with no symptoms (23.1%). A high-improver class (14.2%) decreased from an average of 5.0 to 0 symptoms. A moderate-improver class (32.1%) continued to show symptoms over follow-up (decrease from an average of 6.0 to 2.0 symptoms). Compared with alcohol, a larger proportion constituted the stable-high symptom-trajectory class (13.1%) for marijuana. A smaller proportion (13.3%) was in the stable-low marijuana-symptom trajectory. A relatively small proportion showed an increasing trajectory of marijuana symptoms (4.2%). The most common patterns of change in marijuana symptoms represented an overall reduction in symptoms (46%).

Figure 2.

Marijuana symptom trajectories

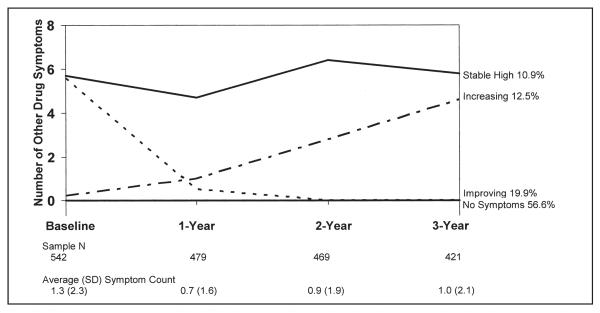

Other-drug trajectories

A four-class solution was selected as the best-fitting model among those tested (BIC = -1,845.77; Figure 3). The next best-fitting model was the five-class solution (BIC = -1,855.50). In the four-class solution for other drugs, a little more than half of the sample reported no symptoms for the drugs included in this analysis (56.6%). An improving class (19.9%, decrease from an average of 5.6 to 0 symptoms [untransformed]), an increasing class (12.5%, increase from an average of 0.2 to 4.6 symptoms [untransformed]), and a stable-high class (10.9%, average of 5.0 to 6.0 symptoms [untransformed]) also were identified.

Figure 3.

Other-drug symptom trajectories. Note: “Other-drug symptoms” is a transformed variable representing the number of symptoms reported across five drugs: hallucinogens, cocaine, opioids, sedatives, and amphetamines.

Joint probabilities of trajectory membership

Alcohol and marijuana

The highest estimated joint probability involved moderate improvers for both alcohol and marijuana (Table 1: probability = .23)—that is, individuals who showed a reduction in alcohol and marijuana symptoms over 1-year follow-up but continued to report symptoms related to both substances over 3 years. The next-highest joint probability involved youths with no marijuana symptoms and a trajectory of low, improved alcohol use (probability = .14). Joint probabilities representing concordant patterns of change ranged from .03 to .23. The lowest joint probabilities (.03-.04) for concordant patterns of change involved trajectories representing high problem severity for both alcohol and marijuana—which reflects the small proportion of the sample classified in high-severity trajectories for alcohol and marijuana. The joint probability for trajectories representing clearly discordant patterns of change (i.e., a decrease in symptoms for one substance and an increase for the other) was very low (combined probability for this pattern < .01). Yet, other types of discordant change patterns, such as stable-high marijuana and improving alcohol trajectories (probability = .10), were observed.

Table 1.

Joint probability of alcohol, marijuana, and other-drug symptom-trajectory groups

| Marijuana |

||||||

| No symptoms |

Stable low |

High improvers |

Moderate improvers |

Increasing | Stable high |

|

|

| ||||||

| Alcohol | ||||||

| Stable low | .037 | .082 | .007 | .000 | .020 | .000 |

| High Improved | .015 | .007 | .090 | .048 | .000 | .010 |

| Moderate improver | .015 | .019 | .046 | .232 | .000 | .081 |

| Low improved | .136 | .022 | .001 | .000 | .001 | .008 |

| Increasing | .000 | .019 | .000 | .000 | .027 | .000 |

| Stable high | .000 | .004 | .003 | .020 | .011 | .040 |

|

|

||||||

| Alcohol |

||||||

| Stable low |

High improvers |

Moderate improvers |

Low improvers |

Increasing | Stable high |

|

|

| ||||||

| Other drugs | ||||||

| Stable low | .154 | .054 | .100 | .188 | .016 | .010 |

| Improving | .000 | .063 | .137 | .003 | .000 | .000 |

| Increasing | .052 | .015 | .042 | .004 | .032 | .000 |

| Stable high | .000 | .015 | .066 | .000 | .000 | .050 |

|

|

||||||

| Marijuana |

||||||

| No symptoms |

Stable low |

High improvers |

Moderate improvers |

Increasing | Stable high |

|

|

| ||||||

| Other drugs | ||||||

| No/low symptoms | .192 | .116 | .065 | .077 | .036 | .039 |

| Improving | .000 | .012 | .075 | .114 | .000 | .009 |

| Increasing | .000 | .036 | .013 | .092 | .022 | .112 |

Note: Concordant cells are bolded (i.e., agreement in direction of change trajectories for two substances).

Alcohol and other drugs

The highest estimated joint probability involved a stable-low other-drug trajectory and a low, improved alcohol trajectory (Table 1: probability = .19). The next-highest joint probability involved those with stable-low trajectories for both alcohol and other drugs (probability = .15). Increasing other-drug use was least likely for those in the stable-high and low-improver alcohol trajectories (probability = .00).

Marijuana and other drugs

When estimated jointly with the six-class solution for marijuana, only three (rather than four) other-drug trajectories were identified: no or low symptoms (51%), improving (21%), and increasing (28%). The stable-high other-drug class that was identified when modeling other drugs separately or modeling other drugs with alcohol did not emerge. The highest joint probability involved no marijuana symptoms and no/low other drug symptoms (Table 1: probability = .19). Focusing on the increasing other-drug trajectory in relation to the marijuana trajectories, estimated joint probabilities were highest for the stable-high marijuana trajectory (probability = .11) and moderate-improver marijuana trajectory (probability = .09). Both of these change patterns suggest risk for increasing other-drug use in the context of continuing marijuana problems. In addition, the discordant pattern of change involving increasing other-drug problems and moderate improvers for marijuana suggests a possible substitution of marijuana for other-drug use, or a change in drug preference, for certain youths.

Cross-drug trajectory subtypes and their associated features

To determine features associated with co-occurring trajectories across alcohol, marijuana, and other drugs simultaneously, we first identified the most common patterns or subtypes of co-occurring cross-drug trajectories. Of 144 possible cross-drug trajectory combinations (6 × 6 × 4), 89 combinations were observed. Subtype analysis indicated that the three-class solution provided the best-fitting model according to BIC (4,488.80). This three-class solution, however, included a class (29%) that combined three of the other-drug trajectory groups (i.e., no symptoms, increasing, and stable-high). The four-class model provided the next best-fitting solution (BIC = 4,509.58) and was selected for further analysis because it provided greater discrimination among the other-drug trajectories while still providing good relative fit to the data.

The four subtypes represented low-improver alcohol trajectory and no marijuana or other-drug symptoms (27%, “low-improver alcohol”); moderate-improver alcohol and marijuana trajectories and no other-drug symptoms (22%, “moderate improvers for alcohol and marijuana”); moderate-improver trajectories for alcohol and marijuana and decreasing other-drug symptoms (32%, “improvers for all drugs”); and moderate improvers for alcohol, stable-high marijuana, and increasing other-drug symptoms (19%, “stable-high marijuana symptoms”). The “stable-high marijuana symptoms” subtype is the only one that included an opposite pattern of change involving moderate improvers for alcohol and increasing other-drug symptoms.

To examine associated features of the subtypes, a separate analysis specified a four-class model that included covariates (demographic characteristics, diagnoses of conduct disorder and depression). The addition of covariates resulted in improved model fit (BIC = 4,407.93), compared with the four-class model without covariates. Wald tests for the difference of the means and probabilities between classes indicated significant between-group differences for gender, ethnicity, age, conduct disorder, and depression (p’s < .01; Table 2). The low-improvers for alcohol subgroup had a high estimated proportion of females (76%), tended to be younger compared with the other subgroups (mean age = 15.9), and had a relatively high likelihood of depression at baseline (62%). Two subtypes had relatively high estimated proportions of males and youths with conduct disorder: (1) moderate improvers for alcohol and marijuana and (2) improvers for all drugs. The stable-high marijuana-symptoms subtype also had a relatively high estimated proportion of males, as well as a relatively high likelihood of conduct disorder (74%) and depression (63%).

Table 2.

Demography and co-occurring psychopathology for four common subtypes of alcohol, marijuana, and other-drug symptom trajectories

| Estimated proportion | Low improving for alcohol (27%) |

Moderate improvers for alcohol and marijuana (22%) |

Improvers for all drugs (32%) |

Stable-high marijuana and other drug symptoms (21%) |

Wald statistic |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demography | |||||

| Gender, % male | 24.3 | 74.8 | 66.1 | 78.2 | 34.6† |

| Ethnicity, % white | 72.8 | 49.9 | 96.9 | 96.9 | 30.3† |

| Age, meana | 15.9 | 16.5 | 17.1 | 16.1 | 30.9† |

| SES, meana | 3.2 | 3.4 | 2.7 | 2.8 | 7.4 |

| Lifetime DSM-IV psychopathology |

|||||

| Conduct disorder, % ever | 36.6 | 75.1 | 86.4 | 74.4 | 43.5† |

| Depression, % ever | 62.0 | 21.7 | 55.9 | 63.0 | 14.8† |

Notes: “Low improvers for alcohol” class represents those with a low improving alcohol trajectory and no marijuana or other-drug symptoms. “Moderate improvers for alcohol and marijuana” represents adolescents with moderate improvement in alcohol and marijuana and no other-drug symptoms. “Improvers for all drugs” includes moderateimprover trajectories for alcohol and marijuana and decreasing other-drug symptoms. “Stable-high marijuana and other-drug symptoms” class includes moderate improvers for alcohol, stable-high marijuana, and increasing otherdrug symptoms; this subtype is the only one that included an opposite pattern of change involving moderate improvers for alcohol and increasing other-drug symptoms. “Depression” includes major depression and dysthymia. SES = socioeconomic status; DSM-IV = Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition.

Standard deviations not available from model estimation.

p < .01.

Discussion

This study identified prototypical patterns of change in DSM-IV abuse and dependence symptoms related to alcohol, marijuana, and other drugs among treated adolescents through 3-year follow-up. It extends the existing literature on substance-use trajectories (e.g., Clark et al., 2006; Tucker et al., 2005) to treated adolescents over longer-term follow-up. Subtype analysis of cross-drug trajectories indicated that three of the four subtypes identified represented generally concordant patterns of cross-drug change involving low or reduced symptom severity across alcohol, marijuana, and other drugs. Only one of the four cross-drug trajectory sub-types included a discordant pattern of change across substances, representing stable-high marijuana problems in the context of a decrease in alcohol problems and an increase in other-drug symptoms (19% of the sample). Analysis of features associated with the cross-drug subtypes provided further support for male gender as a predictor of chronic course and support for both conduct disorder and depression as predictors of trajectory type.

The similarity in the number and shape of the alcohol and marijuana symptom trajectories identified in this study suggest similar overall patterns of change for these two substances. In addition, the cross-drug subtype analysis indicated that the majority of youths were classified into sub-types representing low or improving symptoms for both alcohol and marijuana—which suggests that treatment has general effects in reducing substance problems for a majority of adolescents. Important differences in the alcohol and marijuana trajectories exist, however. Specifically, an asymptomatic class was identified for marijuana but not for alcohol. Nevertheless, the proportion in the stable-high trajectory for marijuana was double that for alcohol (13% vs 6%)—which suggests the greater chronicity of marijuana-related problems for some youths in this sample.

Of some concern, an increasing trajectory class was identified for alcohol (3%), marijuana (4%), and other drugs (12%). Other studies (e.g., Brown et al., 2001; Godley et al., 2004) also have identified increasing trajectories of post-treatment substance involvement, although, on average, youths tend to improve (Williams et al., 2000). The increasing substance-problem trajectories need to be understood in the context of adolescent development, when experimentation with alcohol and other drugs peaks. The higher proportion in the increasing other-drug trajectory, compared with the increasing trajectories for alcohol or marijuana, may reflect the typical sequence of drug involvement, in which alcohol and marijuana use commonly precedes heavy, problematic use of other drugs (e.g., Ellickson et al., 1992).

Although an increasing-trajectory class was identified for alcohol, marijuana, and other drugs, the cross-drug sub-type analysis identified only one subtype (i.e., stable-high marijuana) that included an increasing trajectory. The stable-high marijuana subtype involved moderate improvement in alcohol and increasing other-drug symptoms. This discordant pattern suggests the possibility of drug substitution or a change in drug preference from alcohol to other drugs. The processes underlying this discordant pattern of change remain to be determined and would have important implications for tailoring treatment to prevent an increase in other-drug use for this subgroup.

In addition, treatment for the stable-high marijuana subgroup appears to have had little effect on marijuana symptoms. Although there appeared to be some effect of treatment on alcohol symptoms, this reduction occurred in the context of increasing other-drug symptoms, suggesting the need for more intensive treatment not only to reduce marijuana symptoms but also to prevent an increase in symptoms related to other-drug use in this adolescent subgroup.

Analysis of features associated with the four cross-drug subtypes of change indicated, as reported in other studies (e.g., Godley et al., 2004; Tapert et al., 2003), that males were more likely to report continuing substance-related problems and that females and younger adolescents were more likely to be represented in lower-severity trajectories across substances. With regard to psychopathology, depression was associated with low/improving trajectories across drugs, as well as with more severe trajectories (i.e., “stable-high marijuana symptoms”), likely interacting with both gender and conduct disorder in predicting clinical course. The interaction of depression with other characteristics, such as gender and conduct problems, may help to explain some of the inconsistent findings for depression across studies. Conduct disorder, by contrast, was more consistently associated with subtypes that included trajectories representing continuing problems, as found in other studies (e.g., Waldron et al., 2005).

Both conduct disorder and depression were associated with the stable-high marijuana subtype, which included trajectories of moderate improvement for alcohol and increasing other-drug symptoms. The greater severity of co-occurring psychopathology associated with this subtype does not necessarily help to explain the discordant patterns of change across drugs. It does, however, suggest a candidate process (i.e., severe co-occurring psychopathology) that may underlie the continuing high severity of substance-related problems in this subgroup. The overall severity and chronicity of substance-related problems and the greater degree of psychopathology in this subgroup point to the importance of intensive, continuing care for this high-risk group.

As in other types of analyses, sample characteristics influence the number and type of trajectories identified, as well as the predictors of the trajectory classes. For example, although similar trajectories were identified in this study and in earlier analyses of a limited subset of the sample used here (Chung et al., 2003), conduct disorder and depression did not distinguish the trajectories identified in the earlier analyses, likely owing, in part, to the more restricted nature of the earlier sample. Thus, although the overall pattern of results regarding trajectory types and predictors was generally consistent with prior research, the study results warrant replication.

Certain study limitations need to be considered. Generalizability of results to the population of adolescents may be limited, because the majority of participants were recruited from addictions treatment and were primarily white. Furthermore, retrospective, self-reported data on substance-related symptoms may be subject to bias. The cross-drug subtyping analysis captured the most frequently observed patterns of change but was limited in representing less common patterns of change across drugs (e.g., increasing alcohol and marijuana trajectories), which were examined in dual-trajectory analyses.

Alcohol and marijuana symptoms tended to show a similar, improving pattern of change over 3-year follow-up for a majority of treated youths, although discordant cross-drug patterns of change also were observed. In addition to understanding how change in one substance may affect the use of another, research is needed to examine how changes in co-occurring psychopathology over time, such as depression and conduct disorder, affect the course of substance-related symptoms. The study findings emphasize the need for continuing, and perhaps more intensive, intervention that is targeted to certain subgroups of youths, particularly those with conduct disorder, to maintain and enhance initial treatment gains over longer-term follow-up.

Footnotes

This research was supported by National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism grants K01 AA00324, K02 AA00249, K02AA 00291, R01 AA014357, and R01 AA133397. Portions of this study were presented at the 2004 meeting of the American Psychological Association, Honolulu, Hawaii.

References

- AMERICAN PSYCHIATRIC ASSOCIATION . Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV) Washington, DC: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- BROWN SA, D’AMICO EJ, MCCARTHY DM, TAPERT SF. Four-year outcomes from adolescent alcohol and drug treatment. J. Stud. Alcohol. 2001;62:381–388. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2001.62.381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BROWN SA, TAPERT SF, TATE SR, ABRANTES AM. The role of alcohol in adolescent relapse and outcome. J. Psychoact. Drugs. 2000;32:107–115. doi: 10.1080/02791072.2000.10400216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CHUNG T, MAISTO SA. Relapse to alcohol and other drug use in treated adolescents: Review and reconsideration of relapse as a change point in clinical course. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2006;26:149–161. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2005.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CHUNG T, MAISTO SA, CORNELIUS JR, MARTIN CS. Adolescents’ alcohol and drug use trajectories in the year following treatment. J. Stud. Alcohol. 2004;65:105–114. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2004.65.105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CHUNG T, MARTIN CS, GRELLA CE, WINTERS KC, ABRANTES AM, BROWN SA. Course of alcohol problems in treated adolescents. Alcsm Clin. Exp. Res. 2003;27:253–261. doi: 10.1097/01.ALC.0000053009.66472.5E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CLARK DB, JONES BL, WOOD DS, CORNELIUS JR. Substance use disorder trajectory classes: Diachronic integration of onset age, severity, and course. Addict. Behav. 2006;31:995–1009. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2006.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CLARK DB, POLLOCK NA, BUKSTEIN OG, MEZZICH AC, BROMBERGER JT, DONOVAN JE. Gender and comorbid psychopathology in adolescents with alcohol dependence. J. Amer. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiat. 1997;36:1195–1203. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199709000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ELLICKSON PL, HAYS RD, BELL RM. Stepping through the drug use sequence: Longitudinal scalogram analysis of initiation and regular use. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 1992;101:441–451. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.101.3.441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FIRST MB, SPITZER RL, GIBBON M, WILLIAMS JBW. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders, Research Version, Non-Patient Edition (SCID-I/NP) Biometrics Research, New York State Psychiatric Institute; New York: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- GODLEY SH, DENNIS ML, GODLEY MD, FUNK RR. Thirty-month relapse trajectory cluster groups among adolescents discharged from outpatient treatment. Addiction. 2004;99(Suppl. No. 2):129–139. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2004.00860.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HOLLINGSHEAD AB. Four-Factor Index of Social Status. Department of Sociology, Yale University; New Haven, CT: 1975. [Google Scholar]

- HSER Y-I, GRELLA CE, HUBBARD RL, HSIEH S-C, FLETCHER BW, BROWN BS, ANGLIN MD. An evaluation of drug treatments for adolescents in 4 U.S. cities. Arch. Gen. Psychiat. 2001;58:689–695. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.58.7.689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- JONES BL, NAGIN DS, ROEDER K. A SAS procedure based on mixture models for estimating developmental trajectories. Sociol. Meth. Res. 2001;29:374–393. [Google Scholar]

- KAUFMAN J, BIRMAHER B, BRENT D, RAO U, FLYNN C, MORECI P, WILLIAMSON D, RYAN N. Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Age Children-Present and Lifetime Version (K-SADS-PL): Initial Reliability and Validity Data. J. Amer. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiat. 1997;36:980–988. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199707000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MARTIN CS, KACZYNSKI NA, MAISTO SA, BUKSTEIN OM, MOSS HB. Patterns of DSM-IV alcohol abuse and dependence symptoms in adolescent drinkers. J. Stud. Alcohol. 1995;56:672–680. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1995.56.672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MARTIN CS, KACZYNSKI NA, MAISTO SA, TARTER RE. Polydrug use in adolescent drinkers with and without DSM-IV alcohol abuse and dependence. Alcsm Clin. Exp. Res. 1996;20:1099–1108. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1996.tb01953.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MARTIN CS, POLLOCK NK, BUKSTEIN OG, LYNCH KG. Inter-rater reliability of the SCID alcohol and substance use disorders section among adolescents. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2000;59:173–176. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(99)00119-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NAGIN DS. Analyzing developmental trajectories: A semiparametric, group-based approach. Psychol. Meth. 1999;4:139–157. [Google Scholar]

- NAGIN DS, TREMBLAY RE. Analyzing developmental trajectories of distinct but related behaviors: A group-based model. Psychol. Meth. 2001;6:18–34. doi: 10.1037/1082-989x.6.1.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TAPERT SF, MCCARTHY DM, AARONS GA, SCHWEINSBURG AD, BROWN SA. Influence of language abilities and alcohol expectancies on the persistence of heavy drinking in youth. J. Stud. Alcohol. 2003;64:313–321. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2003.64.313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TUCKER JS, ELLICKSON PL, ORLANDO M, MARTINO SC, KLEIN DJ. Substance use trajectories from early adolescence to emerging adulthood: A comparison of smoking, binge drinking, and marijuana use. J. Drug Issues. 2005;35:307–332. [Google Scholar]

- VERMUNT J, MAGIDSON J. Latent Gold. Version 3.0 Statistical Innovations; Belmont, MA: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- WALDRON HB, TURNER CW, OZECHOWSKI TJ. Profiles of drug use behavior change for adolescents in treatment. Addict. Behav. 2005;30:1775–1796. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2005.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WILLIAMS RJ, CHANG SY, ADDICTION CENTRE ADOLESCENT RESEARCH GROUP A comprehensive and comparative review of adolescent sub stance abuse treatment outcome. Clin. Psychol. Sci. Pract. 2000;7:138–166. [Google Scholar]

- WINTERS KC, LATIMER W, STINCHFIELD RD. The DSM-IV criteria for adolescent alcohol and cannabis use disorders. J. Stud. Alcohol. 1999;60:337–344. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1999.60.337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]