Abstract

Target of rapamycin (TOR) is an evolutionarily conserved serine/threonine protein kinase that functions as a central regulator of cellular growth and metabolism by forming two distinct complexes: TOR complex 1 (TORC1) and TORC2. As well as TORC1, TORC2 plays a key role in regulation of cell growth. But little is known about how TORC2 regulates cell growth. The transcription factor Myc also plays a critical role in cell proliferation and growth. Here we report that TORC2 and Myc regulate cell growth via a common pathway. Expression of Myc fully rescued growth defects associated with lst8 and rictor mutations, both of which encode essential components of TORC2. Furthermore, loss of TORC2 disrupted the nuclear localization of Myc, and inhibited Myc-dependent transcription. Together, our results reveal a Myc-dependent pathway by which TORC2 regulates cell growth.

The Target of rapamycin (TOR) signaling pathway consists of a set of biochemical processes, which in response to environmental cues and growth factors regulates organismal and cellular growth. TOR is an evolutionarily conserved serine/threonine protein kinase and functions as a core catalytic component of two distinct multiprotein complexes, TOR complex 1 (TORC1) and TORC21,2,3. TORC1 controls cell autonomous growth in response to nutrient availability and growth factors, whereas mTORC2 mediates cell proliferation and cell survival by activating several kinases within the AGC family, including AKT, serum and glucocorticoid-regulated kinase (SGK), and protein kinase C (PKC)4,5.

Although the signaling networks regulated by TORC2 are not completely understood, studies in mice, Drosophila, and Caenorhabditis elegans have demonstrated a role for TORC2 in cell growth6,7,8,9. Thus, TORC2 is emerging as a pivotal player in many cancers10,11. As a downstream target of TORC2, AKT plays essential roles in several important cellular processes, including growth, proliferation, survival, and metabolism12. Studies in multiple systems have demonstrated that TORC2 inactivates FOXO (forkhead transcription factors of the O-class) through AKT signaling, but it is clear that AKT and FOXO do not mediate TORC2-regulated cell growth6,7,9,13. It is therefore critical to identify signaling pathways that act downstream of TORC2 to regulate cell growth.

The myc family of proto-oncogenes encode the transcription factors C-myc, N-myc, and L-myc14. Myc proteins play pivotal roles in cell growth and proliferation through the transcriptional regulation of a large number of target genes. As such, dysregulation of Myc contributes to the genesis of many human cancers14,15. Drosophila has a single myc gene (dmyc), which plays a key role in controlling cell size and growth rates by regulating the transcription of mRNAs, ribosomal RNA, and small noncoding RNAs16,17. Hypomorphic dmyc mutations reduce the rate of growth and final size of animals18,19,20,21, and dMyc overexpression results in cells and animals that are larger than normal22,23,24.

Myc has been shown to interact with the TOR pathway. In Drosophila, dMyc is an important mediator of TOR-dependent growth and metabolism25, and inhibition of TOR leads to the post-transcriptional down-regulation of dMyc16,17. In mammalian cells, a large-scale quantitative phosphoproteomics study has shown that TOR phosphorylates C-Myc at Ser7726. Moreover, similar hypogrowth phenotypes are seen in dmyc, lst8, and rictor mutant animals (the latter two encode essential components of TORC2), suggesting that Myc is an essential link between TORC2 and cell growth7,9,23.

Using the Drosophila model system, we found that both cellular and organismal growth defects of dmyc mutant animals were not exacerbated by the loss of LST8. Ectopic expression of dMyc completely rescued the growth defects of both lst8 and rictor mutant animals, including reduced body weight and shrunken eyes and wings. Moreover, the nuclear localization of dMyc was disrupted in lst8 or rictor mutant cells. Furthermore, gene expression profiling revealed that a large set of growth related genes was dysregulated in dmyc, lst8, and rictor mutant animals. Our findings suggested that Myc functions downstream of TORC2 to regulate cell growth.

Materials and Methods

Drosophila stocks

The w1118 (wild-type control), w hs-flp;Act>CD2>Gal4,UAS-GFP/SM5-TM6B, FM7/l;CyO/Sp, FM7;TM2/TM3, ub-RFP hs-flp FRT19A, lst81 FRT19A, dmP0FRT19A/CDX, dmP0 lst81 FRT19A/CDX, lst81 hs-flp ub-RFP FRT19A, dmP0 hs-flp ub-RFP FRT19A, rictorΔ1, lst81;en-gal4/CyO, lst81;GMR-gal4/CyO, lst81 FRT19A/FM7;Tub-dmyc/TM6B, rictorΔ1 FRT19A/FM7; Tub-dmyc/TM6B and pink1B9 were kept or generated in Dr. T. Wang’s lab. The yw; Tub-HA-dmyc flies were obtained from Dr. P. Gallant. The dmP0 and UAS-dmyc flies were gifts from Dr. R. Eisenman. All fly stocks were maintained at 22–25 °C on standard medium unless otherwise specified. Heat shock-induced experiments were carried out by shifting flies to 37 °C for 30 mins to 1 hour at the 1st instar lava stage (for discs) or at the 6–8 hour embryo stage for fat body.

Immunostaining

Fat body tissue from third-instar larvae was dissected, fixed with 8% paraformaldehyde (PFA) dissolved in phosphate-buffered saline, and labeled with antibodies against dMyc (1:50; gift Dr. R. Eisenman), followed by Alexa Fluor 488 goat anti-mouse IgG secondary antibodies (1:1000; Invitrogen), or FITC phalloidin (green) and Hoechst 33342 (1:1000). Images were acquired using a Nikon Eclipse microscope equipped with Nikon DS-Qi1Mc camera.

Flow cytometric analysis

First instar larvae of lst81 hs-flp ub-RFP FRT19A/dmP0 lst81 FRT19A, dmP0 hs-flp ub-RFP FRT19A/dmP0 lst81 FRT19A flies were heat shocked at 37 °C for 1 hour. Approximately 30–40 third-instar larval wing discs were dissected, trypsinized, and stained with Hoechst 33342 (Invitrogen). Analysis was performed with a FACS Vantage (BD Biosciences) and data analyzed with Cell Quest (BD Biosciences) software.

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM)

SEM was performed as described9. Briefly, heads were dissected from newly enclosed male flies reared at 25 °C, dehydrated with a series of ethanol dilutions, and immersed in hexamethyldisilazane. Samples were coated with gold/palladium and mounted after the solvent was evaporated off. The samples were examined with a JEOL JSM- 5800 microscope. The area of 20 ommatidia in high-magnification SEM pictures was measured with ImageJ, and the mean ommatidium size was calculated.

Phosphate affinity SDS-PAGE and western blot

Mobility shift of phosphorylated dMyc protein was detected by phosphate affinity SDS-PAGE using acrylamide-pendant phos-tag (Phos-tag AAL-107). Briefly, 50–100 μM phos-tag acrylamide and 100–200 μM MnCl2 were added to normal 6% polyacrylamide gel. After electrophoresis, the gel was washed with transfer buffer containing 1 mM EDTA for 10 min with gentle agitation, and then with transfer buffer without EDTA for 10 min. Proteins were transferred to Immobilon-FL transfer membranes (Millipore). For western blotting, pupae were homogenized in SDS sample buffer with a pellet pestle (Kimble-Kontes), and the proteins were fractionated using SDS-PAGE. The proteins were transferred to Immobilon-FL transfer membranes in Tris-glycine buffer. The blots were probed with mouse anti-HA 1:500 (Cell Signaling), mouse anti-dMyc (1:50), and rabbit anti-α tubulin 1:15000 (Sigma), and subsequently with IRDye 800-labeled anti-mouse IgG and IRDye 680-labeled anti-rabbit IgG (Licor). Signals were detected using an Odyssey infrared imaging system.

RNA-seq analysis

Reads were mapped to the Drosophila genome (BDGP5.25) using TopHat (v2.0.10) by allowing up to two mismatches27. Expression of genes in the RNA-seq data was measured by calculating reads per kilobase per million mapped reads (RPKM). P-values to detect differential expression were calculated by cufflinks (v2.0.2)28. The criteria for differential expressed genes in a mutant were defined as more than two-fold change in RPKM and less than 0.01 in P-values. Gene ontology analysis was performed with DAVID online ( http://david.abcc.ncifcrf.gov/)29.

Results

Myc and TORC2 function in a linear pathway

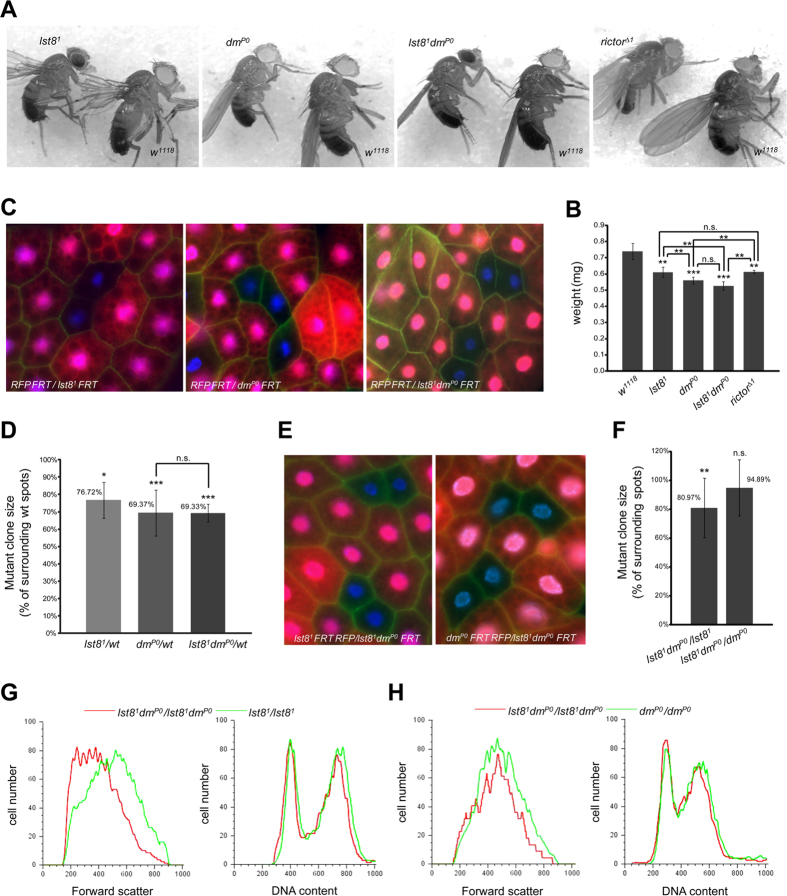

Genetic disruption of TORC2 or Myc cell-autonomously reduces growth rates and cell size, resulting in reduced tissue growth and decreased body weight9,23. We reasoned that TORC2 and Myc might function in the same pathway to regulate cell growth. To test this hypothesis, we analyzed the body size of 4 mutant fly strains: lst81, dmP0, lst81 dmP0, and rictorΔ1, which disrupt the lst8, dmyc, lst8 dmyc, and rictor genes, respectively. Although reduced body size and body weight were observed in lst81, dmP0, and rictorΔ1 flies compared to wild type (w1118), loss of dMyc reduced body weight to a larger extent than loss of lst8 or rictor which both disrupting TORC2 (Fig. 1A,B). Importantly, lst81 dmP0 double mutant animals exhibited body weights similar to dmP0 flies, indicating that loss of TORC2 has less impact on growth in TORC2 may be epistatic to Myc in dmP0 mutant.

Figure 1. Common pathway for TORC2 and Myc regulated cell growth.

(A) Size comparisons between wild type (w1118) and lst81, dmP0, lst81 dmP0, or rictorΔ1 flies. One-day-old male flies were used for the analysis. (B) Quantification of animal weights. Genotypes of one-day-old male flies are shown. Asterisks indicate statistically significant differences (Student’s unpaired t-test, **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001; n.s., not significant). (C–F) Comparisons between lst81 dmP0, lst81, and dmP0 fat body cells. (C) The FLP/FRT system was used to generate mosaic lst81, dmP0, or lst81 dmP0 mutant clones marked by the absence of RFP (hs-flp ub-RFP FRT/lst81 FRT, hs-flp ub-RFP FRT/dmP0 FRT, and hs-flp ub-RFP FRT/lst81 dmP0 FRT animals, respectively) (red, RFP; green, phalloidin; blue, DAPI). (D) Relative size of lst81, dmP0, or lst81 dmP0 cells compared with controls. Asterisks indicate statistically significant differences from wild-type cells (Student’s unpaired t-test, ***p < 0.001; n.s., not significant). (E) The FLP/FRT system was used to generate mosaic lst81 dmP0 double mutant clones in larval fat bodies of lst81 hs-flp ub-RFP FRT/lst81 dmP0 FRT and dmP0 hs-flp ub-RFP FRT/lst81 dmP0 FRT animals, respectively. The lst81 dmP0 mutant cells are marked by the absence of RFP (red, RFP; green, Phalloidin; blue, DAPI). (F) Relative sizes of lst81 dmP0 double mutant cells compared with lst81 or dmP0 cells. Asterisks indicate statistically significant differences from single mutant cells (Student’s unpaired t-test, **p < 0.01; n.s., not significant). (G and H) Flow cytometry was performed on dissociated wing discs from lst81 hs-flp ub-RFP FRT/lst81 dmP0 FRT and dmP0 hs-flp ub-RFP FRT/lst81 dmP0 FRT animals. Cells lacking lst8 (lst81/lst81; green trace in G), dm (dmP0/dmP0; green trace in H), or lst8 and dm (lst81 dmP0/lst81 dmP0; red trace) were compared. Hoechst 33342 staining was used to assess DNA content (right), and FSC was used to quantify cell size (left).

Using the hs-FLP/FRT system, we next generated clones of mutant cells in heterozygous fat body tissues. Mutant clones were marked by the absence of red fluorescent protein (RFP) and we assessed larval fat body cell size by staining the tissue with phalloidin to visualize cell boundaries (Fig. 1C). Similar to body weight, loss of LST8, which completely disrupts TORC2 activities, reduced cell size to 76.72% of surrounding control cells, whereas loss of dMyc alone or LST8 and dMyc reduce cell size to 69.37% and 69.33% of control values, respectively (Fig. 1D). To compare growth rates between lst81, dmP0, and lst81 dmP0 cells in greater detail we used another mosaic system, in which lst81 dmP0double mutant clones were generated in a lst81 or dmP0single-mutant genetic background (Fig. 1E). Cell size analysis revealed that lst81 dmP0 fat body cells were smaller (80.97%) than neighboring lst81 cells. However, this size reduction was not seen when lst81 dmP0 double mutant cells were generated in a dmP0 genetic background (Fig. 1E,F), indicating that loss of dMyc exacerbated growth defects associated with lst81, but loss of LST8 did not affect dmP0 cells.

We next generated double mutant lst81 dmP0 clones of cells in lst81 or dmP0 developing wing discs. Cell size was examined using fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) and forward scatter (FSC) analysis was used to measure cell volumes. This analysis confirmed that loss of dMyc further reduced the size of lst81 mutant cells, but the loss of LST8 did not affect dmP0 mutant cells (Fig. 1G,H, left panels). DNA profiles demonstrated that loss of TORC2 and dMyc did not alter cell cycle phasing (Fig. 1G,H, right panels), consistent with previous findings that reductions in cell size associated with the loss of LST8 and dMyc do not result from changes in cell proliferation. These data suggest that dMyc is a potential downstream effector of the TORC2 signaling pathway to mediated cell growth. However, given the essential role of dMyc in organismal growth and development, disrupting TORC2 signaling through the loss of LST8 will likely not abrogate dMyc function completely. This may explain why reductions in cell size were more remarkable in dmP0, and lst81 dmP0mutant cells than in lst81 cells.

Myc functions downstream of TORC2 to regulate cell growth

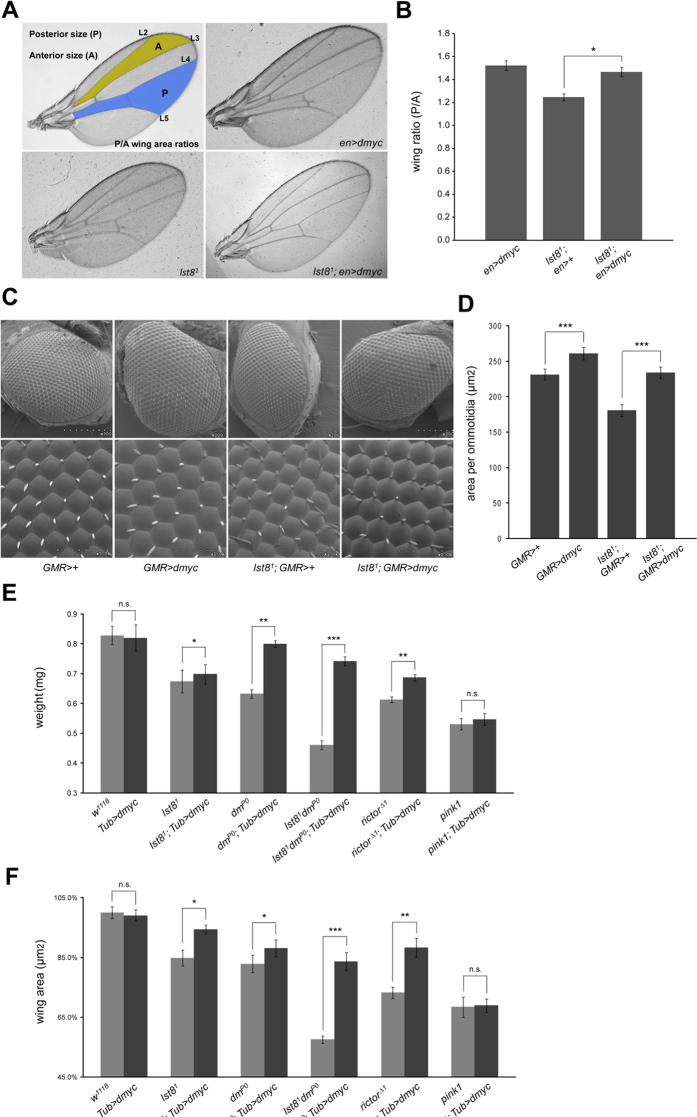

To determine whether dMyc functions downstream of TORC2 signaling, rescuing experiments were performed in which engrailed-Gal4 (en-Gal4) was used to drive expression of UAS-dmyc in the posterior compartment of developing wings in lst81 animals. Expression of dMyc in lst81 animals rescued cell growth within the posterior compartment without affecting the anterior compartment (Fig. 2A,B).

Figure 2. Rescue of TORC2-associated growth defects by dMyc expression.

(A–B) Overexpression of dMyc increased the size of the posterior wing compartment in lst8 mutants. The en-GAL4 was used to drive UAS-dmyc expression in the posterior compartment of the wing (en>dmyc: en-gal4/UAS-dmyc). Posterior size (P) and anterior size (A) were assessed by measuring the area between vein L4 and L5 (blue, P) and the area between vein L2 and L3 (yellow, A) (B) The P/A compartment ratio for en>dmyc, lst81; en>+, and lst81; en>dmyc wings (15 wings per genotype) are shown. Statistical analysis indicates that dMyc overexpression rescued the lst8 mutant phenotype. Asterisks indicate statistically significant differences (Student’s unpaired t-test, ***P < 0.001). (C–D) Overexpression of dMyc increases the size of ommatidia in lst8 mutants. (C) Lateral view of compound eyes from GMR>dmyc (GMR-gal4/UAS-dmyc), lst81; GMR>+, and lst81; GMR>dmyc animals. SEM magnification is 200× or 1000× for upper and lower panels, respectively. (D) Ommatidial size for GMR>dmyc, lst81; GMR>+, and lst81; GMR>dmyc eyes. Five eyes of each genotype were analyzed (Student’s unpaired t-test, ***P < 0.001). (E–F) The tub-dmyc transgene rescued growth defects associated with lst81 or rictorΔ1 flies. Body weight (E) and wing area (F) were analyzed. One hundred one-day-old male flies of each genotype were used to assess body weight, and at least 10 wings per genotype were used to calculate wing area. Asterisks indicate statistically significant differences between flies with the tub-dmyc transgene or not (Student’s t-test, **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001; n.s., not significant).

Considering that different tissues exhibit differences in growth regulation, we next examined the adult compound eye to determine the general relationship between TORC2 and dMyc. Similar results were obtained in the eye. Overexpression of dMyc using GMR-Gal4 significantly increased ommatidial size in lst81 mutant eyes. Similar size effects were seen when dMyc was overexpressed in the wild-type background (Fig. 2C,D). These data support the hypothesis that dMyc participates in TORC2-driven cell growth. However, as overexpression of dMyc by the Gal4/UAS system causes overgrowth of cells30 (Fig. 2C,D), dMyc and TORC2 might also drive cell growth via parallel pathways.

To more precisely assess the interaction between loss of TORC2 and dMyc overexpression, we moderately overexpressed dMyc using the tubulin promoter (Tub-dmyc). This construct did not drive cell overgrowth31, as wing size and body weight were unaffected by the ubiquitous expression of dMyc. In contrast, growth phenotypes of dmP0 animals were strongly rescued by Tub-dmyc (Fig. 2E,F). In lst81, rictorΔ1, and lst81 dmP0 mutant animals, the reduced body weight and shrunken wings were completely rescued by the Tub-dmyc transgene. As a negative control, growth reduction caused by pink1 depletion was unaffected by dMyc overexpression, suggesting that dMyc only rescues growth defects caused by disruptions in TORC2 signaling. These findings strongly supported of our hypothesis that Myc functions as a downstream effector of TORC2 to affect TORC2-mediated cell growth.

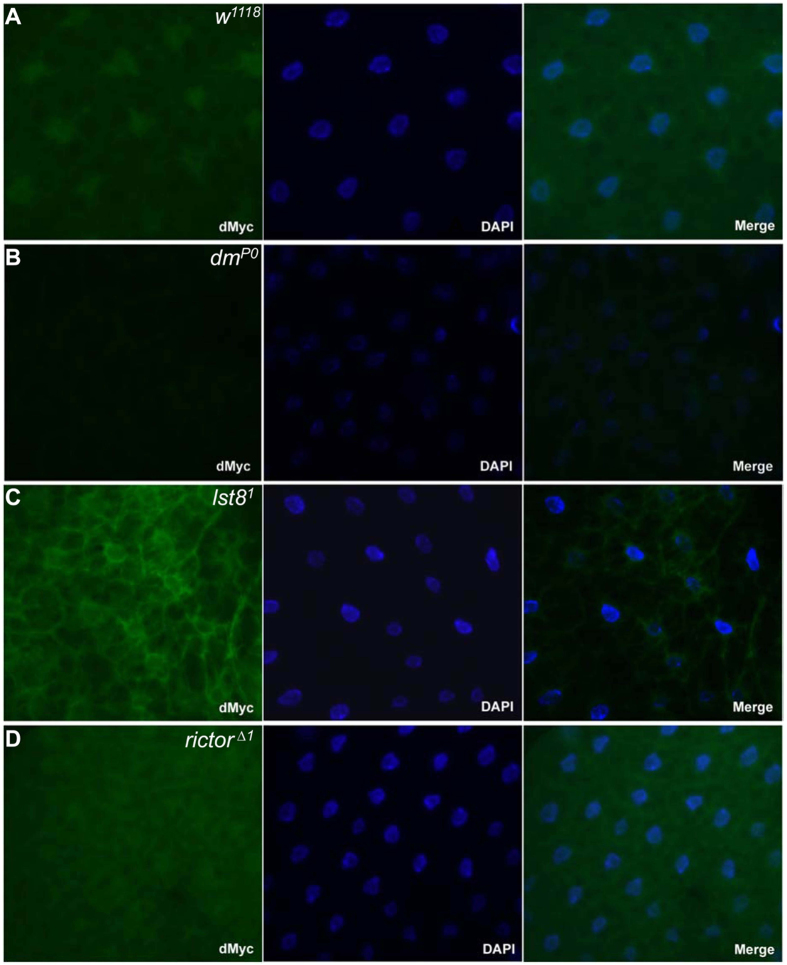

Loss of Myc function upon disruption of TORC2

As a transcription factor, Myc predominantly localizes to the nucleus. As TORC2 might affect cell growth by modulating dMyc pathway, we hypothesized that TORC2 may affect the subcellular localization of dMyc. Immunolabeling experiments were performed using larval fat body tissue to monitor changes in dMyc localization. Antibodies against dMyc revealed that endogenous dMyc localized exclusively to the nucleus in wild-type larval fat body cell, while dMyc staining was dramatically reduced in dmP0 cells (Fig. 3A,B). In fat body tissue lacking LST8 or Rictor, a large portion of dMyc was detected outside of the nucleus, failing to overlap with Dapi (Fig. 3C,D).

Figure 3. Loss of TORC2 disrupts the nuclear localization of dMyc.

Immunohistochemistry was used to detect endogenous dMyc protein (green) in larval fat body cells of (A) wild-type, (B) dmP0, (C) lst81, and (D) rictorΔ1 mutant lava. Hoechst 33342 staining was used to indicate the nucleus (blue).

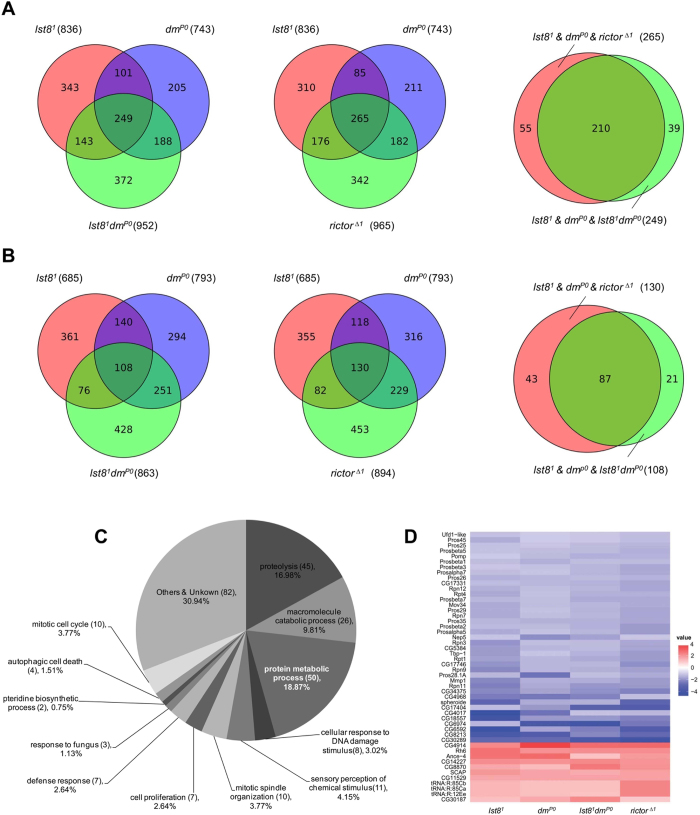

As loss of TORC2 disrupted dMyc nuclear localization, we reasoned that TORC2 might also affect the transcriptional activity of dMyc. To test this hypothesis, we used RNA-sequencing (RNA-seq) to compare mRNA levels of wild-type, lst81, dmP0, lst81 dmP0, and rictorΔ1 animals. Large sets of genes were down-regulated in lst81 (836), dmP0 (743), lst81 dmP0 (952), and rictorΔ1 (965) tissue (Fig. 4A), indicating transcriptional changes. The number of overlapping genes among the different mutant lines was remarkable. There were 249 overlapping genes among lst81, dmP0, and lst81 dmP0 tissues, and 265 overlapping genes among lst81, dmP0, and rictorΔ1 tissues. Two-hundred and ten genes were downregulated at all 4 mutant conditions (Fig. 4A). Genes were also up-regulated in lst81 (685), dmP0 (793), lst81 dmP0 (862), and rictorΔ1 (894) tissues (Fig. 4B). There were 108 overlapping genes among lst81, dmP0, and lst81 dmP0 tissues, and 130 overlapping gene among lst81, dmP0, and rictorΔ1 tissues. Eighty-seven were up-regulated at all 4 mutant conditions (Fig. 4B).

Figure 4. Transcription of dMyc-regulated genes is affected by loss of lst8and rictor.

(A and B) Venn diagrams showing the overlap of downregulated (A) and upregulated (B) genes between the four analyzed genotypes: lst8, dmyc, lst8 dmyc, and rictor. The number of genes down-regulated and/or up-regulated in all 4 studies is shown in the center of the loden area of the right panels. The overlaps were tested by exact hypergeometric probability (p < 0.001). (C) Gene ontology classification of the 265 genes affected by the lst8, rictor, and dm mutations. Counts and percentage in major categories are indicated. (D) Heatmap presentation of gene expression for genes in the “protein metabolic process” category. Relative gene expression is encoded in graduated colors from red (upregulated compared with wild type) to blue (downregulated compared with wild type) according to fold change.

Gene ontology classification of the 265 overlapping genes among lst81, dmP0, and rictorΔ1 are shown in Fig. 4C. Major gene ontology categories included protein metabolic process (18.87%), proteolysis (16.98%), and macromolecule catabolic process (9.81%), which are highly related to cell growth. Together these account for 45.66% of the overlapping genes. We further analyzed genes in the category: “protein metabolic process”. A heat map plot comparing the four genotypes clearly demonstrates the highly similar patterns of expression for genes in this category (Fig. 4D). Transcription levels of these genes were further confirmed with qPCR (Supplementary Fig. S1). We next analyzed genes that overlapping in lst81, lst81 dmP0, and rictorΔ1 but not in dmP0 mutant tissues. Among these 218 genes, there are a large portion of cell death related genes, indicating that TORC2 has additional functions independent of dMyc in some cellular events such as cell death (Supplementary Fig. S2). Moreover, among 836 genes that are down-regulated in the lst81 mutant flies, 101 genes are still down-regulated in the lst81 dmP0 mutant flies when comparing with the dmP0 flies (Supplementary Fig. S3). Similarly, among 685 up-regulated genes in the lst81 mutant tissues, 71 genes are still up-regulated in the lst81 dmP0 double mutant tissues when comparing with the dmP0 tissues (Supplementary Fig. S3). Nevertheless, the highly consistent expression patterns among the 4 mutant stains suggests that TORC2 regulates dMyc transcriptional activity by modulating its nuclear localization.

Discussion

Here we describe a crosstalk between TORC2 and Myc, two regulators of cell growth. The genetic and cell biology studies in Drosophila place TORC2 upstream of MYC in a pathway that regulates cell growth. These results suggest that TORC2 inhibitors may represent effective therapies for treating Myc-driven cancers.

TOR kinase is a highly conserved protein kinase and a central regulator of cell growth. TORC1 has been extensively characterized, but the recent identification of a second TOR complex (TORC2) has complicated the TOR-regulated cell growth pathways. TORC2 regulates growth and metabolism in both mammals and invertebrates6,8,9,32. Recent findings indicate that ribosomes physically interact with TORC2 and that this interaction is required for mTORC2 activation. This suggests a critical role for TORC2 in cell growth regulation33. However, little is known about the regulation of mTORC2 signaling, or the downstream effectors that implement TORC2-mediated cell growth4. Given evidence that TORC2 regulates AKT/FOXO, AKT/FOXO signaling has been considered the major factor acting downstream of TORC2 to control growth. Our findings that AKT- or FOXO does not affect TORC2-mediated cell growth strongly argue against the AKT/FOXO pathway acting downstream of TORC2 in this context9.

In the present study, we found that MYC is required for TORC2-regulated cell growth. Mutations in lst8, rictor, or dmyc had similar growth defects, and lst8 dmyc double mutants did not have more severe growth phenotypes than dmyc mutants. Mosaic analysis in multiple cell types showed that lst8 dmyc double mutant cells had similar growth rates and cell sizes as dmyc mutant cells within the same animals. Moreover, we established that Myc functions downstream of TORC2 in cell growth. Growth phenotypes associated with loss of TORC2 in the retina, wing, fat body, and the entire body were rescued by the overexpression of dMyc.

Myc protein controls metabolism, cell growth, and proliferation by regulating genes transcribed by RNA Polymerase II, and by stimulating transcription by RNA Polymerases I and III15. As Myc is a transcription factor, pathways that regulate the subcellular localization of Myc likely affect its ability to regulate growth and metabolism34. Here we found that the lack of TORC2 activity is associated the cytoplasmic accumulation of dMyc. Consequently, many Myc target genes were dysregulated in lst8 and rictor mutant tissues. TORC2-mediated nuclear localization of Myc may represent a novel mechanism by which Myc activity is regulated.

As master regulators of cell growth and metabolism, TORC1 and Myc exhibit coordinated patterns of activity35. TORC1 activity is required for cancer cell survival, and TORC1 inhibition has remarkable therapeutic efficacy in Myc-driven hematological cancers36. In flies, inhibition of TORC1 by molecular inhibitors, genetic manipulations, or starvation leads to the post-transcriptional downregulation of dMyc followed by the repression of dMyc target genes16,25. In mammals, it has been reported that TORC1 activity is required for efficient c-MYC translation in TSC2-null Elt3 rat leiomyoma cells37, but opposite results have been reported for colorectal cancer cells, in which TORC1 inhibition by rapamycin treatment or knockdown of Raptor results in phosphorylation and accumulation of Myc38. Moreover, in Drosophila intestinal stem cells, excessive TORC1-driven growth in TSC mutants blocked dMyc-induced cell division39. These results challenge the notion that TORC1 inhibitors can be used as therapeutic drugs in Myc-driven cancers.

In some cases, such as hyperactivation of AKT signaling, TORC2 is required for proliferation of tumor cells and subsequent tumor growth33,40. The selective requirement for mTORC2 in tumor development suggests that mTORC2 inhibitors may be of substantial clinical utility40. The PI3K/AKT signaling cascade is known to regulate metabolic processes via discrete effectors, such as the TSC (tuberous sclerosis) complex and FOXOs. TORC2 inactivates the FOXO branch without affecting the TSC/TORC1 branch41,42. It has been demonstrated that FOXO inhibits MYC function to decrease mitochondrial function and to reduce ROS production43,44. Moreover, a central role for TORC2 in cancer metabolic reprogramming has been proposed, wherein mTORC2 signaling increases cellular c-Myc levels by acetylating FOXO independent of AKT45. Here we found that TORC2 controlled cell growth by regulating dMyc via nuclear localization. This regulation of dMyc by TORC2 is likely not through TORC2-mediated inactivation of FOXO, because mutations in lst8 or rictor do not affect dMyc transcription or translation. Moreover, previous reports that TORC2 does not regulate cell growth via AKT/FOXO support the model that TORC2 regulates cell growth via Myc independent of FOXO9. This finding suggests that TORC2 inhibitors may represent an effective way of treating Myc-driven cancers.

Author Contributions

Y.K., H.H. and T.W. designed and performed research; Y.K., H.H., T.C. and T.W. analyzed data; Y.K. and T.W. wrote the paper. All authors approved the final manuscript.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Kuo, Y. et al. Target of Rapamycin Complex 2 regulates cell growth via Myc in Drosophila. Sci. Rep. 5, 10339; doi: 10.1038/srep10339 (2015).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a 973 grant from the Chinese Ministry of Science and Technology to T.W. (2011CB812702 and 2014CB849701). We thank the Bloomington Stock Center, Drs. Drs. R. Eisenman, P. Gallant and B. Edgar for fly stocks. We thank R. Ma, Y. Chen and S. Ren for technical help and valuable comments, and Dr. D. O’keefe for comments on the manuscript. All RNAseq data can be accessed from the NCBI Sequence Read Archive by Gene Expression Omnibus accession number [GSE65691].

References

- Wullschleger S., Loewith R. & Hall M. N. TOR signaling in growth and metabolism. Cell 124, 471–484 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gough N. R. Focus issue: TOR signaling, a tale of two complexes. Sci. Signal 5, eg4 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Betz C. & Hall M. N. Where is mTOR and what is it doing there? J. Cell Biol. 203, 563–574 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zoncu R., Efeyan A. & Sabatini D. M. mTOR: from growth signal integration to cancer, diabetes and ageing. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 12, 21–35 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aimbetov R. et al. Integrity of mTORC2 is dependent on the rictor Gly-934 site. Oncogene. 31, 2115–2120 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guertin D. A. et al. Ablation in mice of the mTORC components raptor, rictor, or mLST8 reveals that mTORC2 is required for signaling to Akt-FOXO and PKCalpha, but not S6K1. Dev. Cell 11, 859–871 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hietakangas V., Cohen S. M. & Re-evaluating A. K. T. regulation: role of TOR complex 2 in tissue growth. Genes. Dev. 21, 632–637 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones K. T., Greer E. R., Pearce D. & Ashrafi K. Rictor/TORC2 regulates Caenorhabditis elegans fat storage, body size, and development through sgk-1. PLoS biology 7, e60 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang T., Blumhagen R., Lao U., Kuo Y. & Edgar B. A. LST8 regulates cell growth via target-of-rapamycin complex 2 (TORC2). Mol. Cell Biol. 32, 2203–2213 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornu M., Albert V. & Hall M. N. mTOR in aging, metabolism, and cancer. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 23, 53–62 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laplante M., Sabatini D. M. mTOR signaling in growth control and disease. Cell 149, 274–293 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearce L. R., Komander D. & Alessi D. R. The nuts and bolts of AGC protein kinases. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 11, 9–22 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacinto E. et al. SIN1/MIP1 maintains rictor-mTOR complex integrity and regulates Akt phosphorylation and substrate specificity. Cell 127, 125–137 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dang C. V. MYC on the path to cancer. Cell 149, 22–35 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eilers M. & Eisenman R. N. Myc’s broad reach. Genes. Dev. 22, 2755–2766 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parisi F. et al. Drosophila insulin and target of rapamycin (TOR) pathways regulate GSK3 beta activity to control Myc stability and determine Myc expression in vivo. BMC Biol. 9, 65 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallant P. Myc function in Drosophila. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 3, a014324 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orian A. et al. Genomic binding by the Drosophila Myc, Max, Mad/Mnt transcription factor network. Genes. Dev. 17, 1101–1114 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hulf T. et al. Whole-genome analysis reveals a strong positional bias of conserved dMyc-dependent E-boxes. Mol. Cell Biol. 25, 3401–3410 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grewal S. S., Li L., Orian A., Eisenman R. N. & Edgar B. A. Myc-dependent regulation of ribosomal RNA synthesis during Drosophila development. Nat. Cell Biol. 7, 295–302 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall L., Rideout E. J. & Grewal S. S. Nutrient/TOR-dependent regulation of RNA polymerase III controls tissue and organismal growth in Drosophila. EMBO J. 31, 1916–1930 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iritani B. M. & Eisenman R. N. c-Myc enhances protein synthesis and cell size during B lymphocyte development. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96, 13180–13185 (1999). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston L. A., Prober D. A., Edgar B. A., Eisenman R. N. & Gallant P. Drosophila myc regulates cellular growth during development. Cell 98, 779–790 (1999). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conacci-Sorrell M., McFerrin L. & Eisenman R. N. An overview of MYC and its interactome. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 4, a014357 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teleman A. A., Hietakangas V., Sayadian A. C. & Cohen S. M. Nutritional control of protein biosynthetic capacity by insulin via Myc in Drosophila. Cell Metab. 7, 21–32 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu P. P. et al. The mTOR-regulated phosphoproteome reveals a mechanism of mTORC1-mediated inhibition of growth factor signaling. Science 332, 1317–1322 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trapnell C., Pachter L. & Salzberg S. L. TopHat: discovering splice junctions with RNA-Seq. Bioinformatics 25, 1105–1111 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trapnell C. et al. Transcript assembly and quantification by RNA-Seq reveals unannotated transcripts and isoform switching during cell differentiation. Nat. Biotechnol. 28, 511–515 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang da W., Sherman B.T. & Lempicki R.A. Systematic and integrative analysis of large gene lists using DAVID bioinformatics resources. Nat. Protoc. 4, 44–57 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Secombe J., Li L., Carlos L. & Eisenman R. N. The Trithorax group protein Lid is a trimethyl histone H3K4 demethylase required for dMyc-induced cell growth. Genes. Dev. 21, 537–551 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de la Cova C., Abril M., Bellosta P., Gallant P. & Johnston L. A. Drosophila myc regulates organ size by inducing cell competition. Cell 117, 107–116 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soukas A. A., Kane E. A., Carr C. E., Melo J. A. & Ruvkun G. Rictor/TORC2 regulates fat metabolism, feeding, growth, and life span in Caenorhabditis elegans. Genes. Dev. 23, 496–511 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zinzalla V., Stracka D., Oppliger W. & Hall M. N. Activation of mTORC2 by association with the ribosome. Cell 144, 757–768 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Z. & Hann S. R. Nucleophosmin is essential for c-Myc nucleolar localization and c-Myc-mediated rDNA transcription. Oncogene. 32, 1988–1994 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan J. C. et al. AKT promotes rRNA synthesis and cooperates with c-MYC to stimulate ribosome biogenesis in cancer. Sci. Signal 4, ra56 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pourdehnad M. et al. Myc and mTOR converge on a common node in protein synthesis control that confers synthetic lethality in Myc-driven cancers. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 110, 11988–11993 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babcock J. T. et al. Mammalian target of rapamycin complex 1 (mTORC1) enhances bortezomib-induced death in tuberous sclerosis complex (TSC)-null cells by a c-MYC-dependent induction of the unfolded protein response. J. Biol. Chem. 288, 15687–15698 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan J. et al. B55beta-associated PP2A complex controls PDK1-directed myc signaling and modulates rapamycin sensitivity in colorectal cancer. Cancer Cell 18, 459–471 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amcheslavsky A., Ito N., Jiang J. & Ip Y. T. Tuberous sclerosis complex and Myc coordinate the growth and division of Drosophila intestinal stem cells. J. Cell Biol. 193, 695–710 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guertin D. A. et al. mTOR complex 2 is required for the development of prostate cancer induced by Pten loss in mice. Cancer Cell 15, 148–159 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu Z. & Tindall D. J. FOXOs, cancer and regulation of apoptosis. Oncogene. 27, 2312–2319 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oh W. J. & Jacinto E. mTOR complex 2 signaling and functions. Cell Cycle 10, 2305–2316 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen K. S. et al. FoxO3A promotes metabolic adaptation to hypoxia by antagonizing Myc function. EMBO J. 30, 4554–4570 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferber E. C. et al. FOXO3a regulates reactive oxygen metabolism by inhibiting mitochondrial gene expression. Cell Death Differ 19, 968–979 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masui K. et al. mTOR complex 2 controls glycolytic metabolism in glioblastoma through FoxO acetylation and upregulation of c-Myc. Cell Metab. 18, 726–739 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.