Abstract

Objectives

To characterize the prevalence of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) among residential care facility (RCF) residents in the United States. To compare patterns of hospital visits and comorbidities to residents without COPD.

Methods

Resident data from the 2010 National Survey of Residential Care Facilities were analyzed. Medical history and information on past-year hospital visits for 8,089 adult residents were obtained from interviews with RCF staff.

Results

COPD prevalence was 12.4%. Compared to residents without COPD, emergency department visits or overnight hospital stays in previous year were more prevalent (p<0.05) among residents with COPD. <3% of residents with COPD had no comorbidities. Arthritis, depression, congestive heart failure, diabetes, coronary heart disease, and asthma were more common (p<0.05) among residents with COPD than those without COPD, but Alzheimer’s disease was less common.

Discussion

COPD is associated with more emergency department visits, hospital stays, and comorbidities among RCF residents.

Keywords: Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, Hospitalization, Comorbidity, Residential facilities

INTRODUCTION

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is a progressive condition characterized by breathing difficulties caused by airflow obstruction. It includes emphysema and chronic bronchitis and, in the United States, is usually attributable to smoking tobacco (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2008). COPD is an important cause of mortality and morbidity in the U.S. (Ford et al., 2013). Individuals with COPD also are likely to suffer from a variety of other chronic conditions, such as cardiovascular disease and cancer (Barr et al., 2009; Cazzola, Bettoncelli, Sessa, Cricelli, & Biscione, 2010; Divo et al., 2012; Feary, Rodrigues, Smith, Hubbard, & Gibson, 2010; Garcia-Olmos et al., 2013; John, Lange, Hoernig, Witt, & Anker, 2006; Lindberg, Larsson, Ronmark, & Lundback, 2011; Nazir & Erbland, 2009; Schnell et al., 2012; Sin & Man, 2005; Soriano, Visick, Muellerova, Payvandi, & Hansell, 2005). As COPD becomes increasingly more severe, impaired lung function and symptoms such as shortness of breath may impact an individual’s ability to perform basic activities.

Approximately 12% of US adults aged 65 years and older report being diagnosed with COPD, but this estimate is based on data from noninstitutionalized adults (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2012). Residents of long-term care facilities such as residential care facilities (RCFs) are not included in these surveys. RCFs provide housing and support services for individuals who cannot live alone, but who do not require the level of care provided by nursing homes (Moss et al., 2011). It is important to look at this population because an estimated 733,000 individuals nationwide lived in RCFs in 2010 (Caffrey et al., 2012). The objectives of this study were to characterize the prevalence of COPD among residents of RCFs in the U.S., as well as to compare patterns of residents’ hospital visits by COPD and comorbidity status.

METHODS

Design and study population

Data analyzed in this report were collected as part of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s National Survey of Residential Care Facilities (NSRCF). The National Center for Health Statistics conducted the NSRCF in 2010. The survey used a stratified two-stage probability sampling design. The first stage was the selection of residential care facilities (RCFs). Lists of licensed RCFs were acquired from licensing agencies in the 50 states and District of Columbia and concatenated to form a sampling frame of nearly 40,000 RCFs. The RCFs surveyed were state-regulated, had 4 or more beds, and provided room and board with at least two meals per day, around-the-clock supervision, and help with personal care or health-related services. Facilities licensed to serve developmentally disabled or severely mentally ill populations exclusively were excluded, as were nursing homes, unless they had a unit or wing meeting the RCF definition and residents who could be evaluated separately from other nursing home residents. The second stage was the selection of residents at the RCFs. Data for 8094 residents aged ≥18 years were obtained from in-person interviews with RCF staff (proxy respondents) of 2302 facilities. The overall weighted survey response rate was 79.4% (the product of the facility weighted response rate and the resident weighted response rate (Moss et al., 2011)). Additional details regarding the design and operation of the survey are available at http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nsrcf.htm. NSRCF was approved by the Research Ethics Review Board of the National Center for Health Statistics.

COPD and comorbidities

For each resident selected, the survey respondent (RCF staff) was asked, “As far as you know, has a doctor or other health professional ever diagnosed [the resident] with any of the following conditions?” The respondent was shown a card with a list of 30 conditions and asked to select all that applied. The list included emphysema, chronic bronchitis, and COPD (each listed separately). These responses were not mutually exclusive and a resident could have more than one of these conditions (for example, emphysema and chronic bronchitis). In this study, COPD was defined as having any of these three conditions. Responses to this question were also used to categorize residents according to comorbidity status for the individual conditions included on the list, as well as categories of comorbidities: circulatory system disorders (congestive heart failure; coronary heart disease; heart attack or myocardial infarction; high blood pressure or hypertension; stroke; other heart condition or heart disease); mental and behavioral disorders (Alzheimer’s disease or other dementia; depression; intellectual or developmental disabilities; serious mental problems [e.g. schizophrenia or psychosis]; other mental, emotional, or nervous conditions); musculoskeletal or connective tissue disorders (arthritis or rheumatoid arthritis; gout, lupus, or fibromyalgia; osteoporosis); eye diseases (glaucoma, macular degeneration); and nervous system disorders (nervous system disorders including multiple sclerosis, Parkinson’s disease, and epilepsy; partial or total paralysis; spinal cord injury; traumatic brain injury; cerebral palsy; muscular dystrophy).

Hospital visits

Survey respondents also were asked the following questions about the resident’s hospital visits in the past 12 months (or in the months since the resident moved into the RCF): “During this time, has [the resident] been treated in a hospital emergency room?”; “During this time, has [the resident] been a patient in a hospital overnight or longer (excluding trips to the emergency room that did not result in a hospital stay)?”; and “How many times has [the resident] been treated in a hospital emergency room over this period?”

Sociodemographic variables

Data was also collected on residents’ sex, age (18–64 years, 65–74 years, 75–84 years, ≥85 years), race/ethnicity (non-Hispanic white, non-Hispanic black, other), education (high school or less, some college or more, unknown), and marital status (married, divorced/separated, widowed, never married).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were conducted using SAS 9.2 (SAS Institute, Inc.) with SUDAAN 10.0.1 (RTI International) to account for the complex sampling design. The nesting variables were RSTRATUM (first stage stratum) and FACID (first stage primary sampling unit). The resident weighting variable was RESFNWT. The design option WOR (sampling without replacement) was used with the variables RPOPFAC (variable for total facilities needed to calculate the finite population correction at the first stage) and POPRES in the TOTCNT statement. (A description of the variables that should be used by other statistical packages is included in the Survey Methodology and Documentation available at http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nsrcf/nsrcf_questionnaires.htm.) Weighted prevalence estimates of COPD with 95% confidence intervals (CI) were obtained by sociodemographic characteristics. Prevalences of hospital visits, overnight stays, and chronic health conditions by COPD status were also calculated. Finally, prevalence of emergency department visits by COPD and comorbidity status was also calculated. T-tests were used to compare residents with COPD to those without COPD. Statistically significant differences were defined as p-value < 0.05.

RESULTS

Out of the 8094 residents for whom data was collected, 5 were missing chronic disease data and were omitted from analyses. Characteristics of the sample population are presented in Table 1. The 8089 residents surveyed represented 732,987 residents nationally. The resident population was predominantly women (69.6%), aged 85 years or older (53.8%), non-Hispanic white (91.1%), had no more than a high school education (50.4%), and widowed (63.2%). At least one of the COPD conditions (chronic bronchitis, emphysema, or COPD) was reported for 12.4% of the study population, corresponding to over 91,000 residents nationally.

Table 1.

Characteristics of study population - National Survey of Residential Care Facilities, 2010.

| Characteristic | Sample size | Weighted no. | %a(95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 8,089 | 732,987 | 100.0 |

| Sex | |||

| Men | 2,582 | 222,710 | 30.4 (29.1–31.7) |

| Women | 5,507 | 510,277 | 69.6 (68.3–70.9) |

| Age (years) | |||

| 18–64 | 1,238 | 77,218 | 10.5 (9.5–11.6) |

| 65–74 | 792 | 62,424 | 8.5 (7.8–9.4) |

| 75–84 | 2,037 | 198,727 | 27.1 (25.9–28.4) |

| 85+ | 4,022 | 394,618 | 53.8 (52.3–55.4) |

| Race/Ethnicity | |||

| White non-Hispanic | 7,197 | 667,486 | 91.1 (90.1–91.9) |

| Black non-Hispanic | 458 | 31,680 | 4.3 (3.8–5.0) |

| Other | 434 | 33,821 | 4.6 (4.0–5.3) |

| Education | |||

| High school or less | 4,514 | 369,024 | 50.4 (48.7–52.2) |

| Some college or more | 2,470 | 252,719 | 34.5 (32.9–36.2) |

| Unknown | 1,105 | 111,244 | 15.2 (13.6–16.9) |

| Marital Statusb | |||

| Married | 957 | 94,583 | 13.1 (12.2–14.1) |

| Divorced/Separated | 932 | 73,094 | 10.1 (9.3–11.0) |

| Widowed | 4,694 | 456,927 | 63.2 (61.6–64.7) |

| Never married | 1,406 | 98,889 | 13.7 (12.6–14.8) |

| History of | |||

| Chronic bronchitis | 199 | 14,483 | 2.0 (1.6–2.4) |

| Emphysema | 103 | 8,635 | 1.2 (0.9–1.5) |

| COPD | 878 | 78,994 | 10.8 (9.9–11.7) |

| Any COPDc | 1,034 | 91,119 | 12.4 (11.5–13.4) |

Weighted percentage and 95% confidence interval.

Marital status was not identified for 100 residents.

Any COPD includes history of chronic bronchitis, emphysema, or COPD.

The prevalence of COPD was higher (p<0.05) among men than women (14.8% vs. 11.4%) and was lower among residents aged 85 years and older (10.3%) compared to the other age groups (Table 2). COPD prevalence did not differ significantly between groups defined by race/ethnicity or level of education, but was significantly lower among married residents (9.8%) compared to residents who were divorced or separated (15.1%), as well as never married residents (13.6%).

Table 2.

COPDa prevalence by sociodemographic characteristics - NSRCF, 2010.

| Characteristic | %b(95% CI) |

|---|---|

| Total | 12.4(11.5–13.4) |

| Sex | |

| Men | 14.8(13.1–16.6) |

| Women | 11.4(10.4–12.5) |

| Age (years) | |

| 18–64 | 14.1(11.5–17.1) |

| 65–74 | 17.0(13.8–20.8) |

| 75–84 | 14.6(12.8–16.6) |

| ≥85 | 10.3(9.2–11.5) |

| Race/Ethnicity | |

| White non-Hispanic | 12.4(11.4–13.4) |

| Black non-Hispanic | 12.7(8.7–18.0) |

| Other | 13.7(10.2–18.2) |

| Education | |

| High school or less | 13.2(11.9–14.6) |

| Some college or more | 11.8(10.3–13.5) |

| Unknown | 11.3(9.1–13.9) |

| Marital Status | |

| Married | 9.8(7.8–12.2) |

| Divorced/Separated | 15.1(12.4–18.3) |

| Widowed | 12.2(11.1–13.5) |

| Never married | 13.6(11.1–16.5) |

Includes history of chronic bronchitis, emphysema, or COPD.

Weighted percentage and 95% confidence interval.

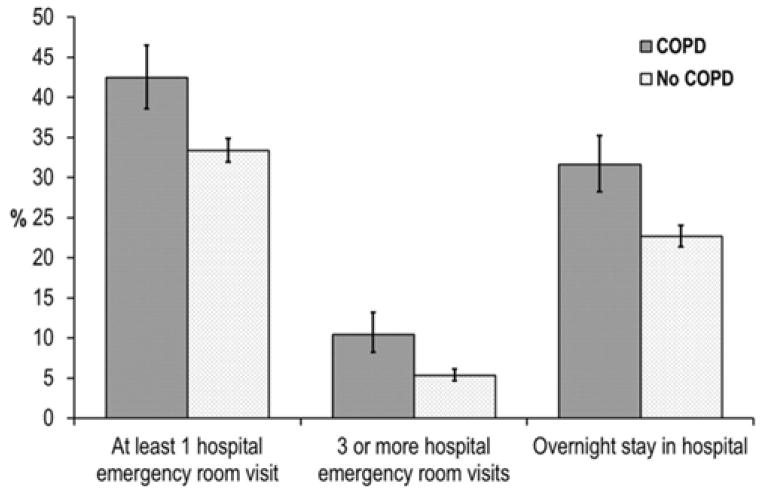

Compared to residents without COPD, those with COPD were significantly more likely to have visited a hospital emergency room in the previous 12 months (42.5% [95% CI: 38.6%, 46.5%] compared to 33.4% [95% CI: 31.9%, 34.8%], p<0.0001), to have made at least 3 visits to a hospital emergency room in that time (10.5% [95% CI: 8.3%, 13.2%] compared to 5.3% [95% CI: 4.7%, 6.1%], p=0.0001), and to have stayed in a hospital overnight (31.6% [95% CI: 28.3%, 35.2%] compared to 22.7% [95% CI: 21.4%, 24.0%], p<0.0001) after adjustment for age differences (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Prevalence of hospital visits and overnight stays in the previous 12 months by COPD status—NSRCF, 2010. Note. COPD = chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; NSRCF = National Survey of Residential Care Facilities.

Compared to residents without COPD, the age-adjusted prevalence of the following chronic conditions was significantly higher among residents with COPD: depression, arthritis, diabetes, coronary heart disease, congestive heart failure, anemia, serious mental problems such as schizophrenia or psychosis, kidney disease, heart attack, and asthma (Table 3). The following conditions were significantly less prevalent among residents with COPD: Alzheimer’s disease or other dementia and nervous system disorders including multiple sclerosis, Parkinson’s disease, and epilepsy. We also grouped categories of chronic conditions. Residents with COPD were more likely to have circulatory system disorders and musculoskeletal or connective tissue disorders than residents without COPD. Overall, the age-adjusted mean number of chronic health conditions (excluding COPD) was higher among residents with COPD (mean: 3.97 vs. 3.25).

Table 3.

Prevalence of individual chronic health conditions by COPD status-NSRCF 2010

| Chronic health condition | Total | COPD | No COPD | Difference in prevalence (COPD-No COPD) | p-value for t-test | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| %a | (95% CI) | % | (95% CI) | % | (95% CI) | |||

| High blood pressure/hypertension | 56.7 | (55.1–58.3) | 59.4 | (55.4–63.3) | 56.4 | (54.6–58.1) | 3.01 | NS |

| Alzheimer’s disease or other dementia | 41.8 | (40.2–43.5) | 33.7 | (30.1–37.5) | 43.0 | (41.3–44.7) | −9.32 | <0.001 |

| Depression | 27.4 | (26.1–28.8) | 31.5 | (28.1–35.1) | 26.8 | (25.4–28.3) | 4.67 | 0.012 |

| Arthritis or rheumatoid arthritis | 27.1 | (25.6–28.6) | 33.7 | (30.1–37.5) | 26.2 | (24.7–27.7) | 7.55 | <0.001 |

| Osteoporosis | 20.4 | (19.1–21.7) | 22.4 | (19.3–25.8) | 20.1 | (18.8–21.5) | 2.28 | NS |

| Diabetes | 17.2 | (16.1–18.3) | 25.3 | (22.1–28.7) | 16.0 | (14.9–17.2) | 9.26 | <0.001 |

| Other heart condition (not listed elsewhere) | 14.4 | (13.3–15.6) | 15.4 | (12.7–18.5) | 14.3 | (13.1–15.5) | 1.12 | NS |

| Coronary heart disease | 13.2 | (12.2–14.4) | 18.0 | (15.2–21.2) | 12.6 | (11.4–13.8) | 5.42 | <0.001 |

| Congestive heart failure | 13.2 | (12.2–14.3) | 26.4 | (23.2–29.9) | 11.3 | (10.4–12.4) | 15.05 | <0.001 |

| Other mental, emotional, or nervous condition | 11.7 | (10.8–12.7) | 14.8 | (12.5–17.6) | 11.2 | (10.3–12.3) | 3.61 | 0.007 |

| Stroke | 10.9 | (10.1–11.8) | 12.4 | (10.1–15.1) | 10.7 | (9.8–11.7) | 1.73 | NS |

| Cancer or malignant neoplasm of any kind | 10.7 | (9.9–11.6) | 10.9 | (8.8–13.4) | 10.7 | (9.8–11.7) | 0.23 | NS |

| Anemia | 9.6 | (8.8–10.6) | 13.5 | (10.9–16.5) | 9.1 | (8.2–10.0) | 4.38 | 0.003 |

| Nervous system disorders including multiple sclerosis, Parkinson’s disease, and epilepsy | 7.7 | (7.0–8.5) | 5.8 | (4.3–7.7) | 8.0 | (7.2–8.8) | −2.15 | 0.020 |

| Serious mental problems such as schizophrenia or psychosis | 7.6 | (6.8–8.5) | 10.9 | (8.6–13.8) | 7.1 | (6.3–8.0) | 3.84 | 0.004 |

| Gastrointestinal problems | 7.5 | (6.7–8.4) | 8.6 | (6.6–11.2) | 7.3 | (6.5–8.3) | 1.3 | NS |

| Glaucoma | 6.3 | (5.6–7.0) | 5.7 | (4.2–7.7) | 6.3 | (5.6–7.1) | −0.61 | NS |

| Macular degeneration | 5.9 | (5.3–6.6) | 6.8 | (5.2–8.8) | 5.8 | (5.1–6.6) | 0.95 | NS |

| Kidney disease | 5.7 | (5.1–6.4) | 9.6 | (7.6–12.1) | 5.1 | (4.5–5.9) | 4.47 | <0.001 |

| Heart attack/myocardial infarction | 4.2 | (3.7–4.8) | 6.4 | (4.6–8.7) | 3.9 | (3.4–4.5) | 2.47 | 0.021 |

| Asthma | 4.2 | (3.7–4.8) | 14.5 | (12.0–17.3) | 2.7 | (2.3–3.3) | 11.71 | <0.001 |

| Intellectual or developmental disability such as mental retardation, severe autism, or Down syndrome | 3.3 | (2.9–3.9) | 2.9 | (2.0–4.3) | 3.4 | (2.9–4.0) | −0.47 | NS |

| Gout, lupus, or fibromyalgia | 2.6 | (2.2–3.0) | 3.7 | (2.6–5.2) | 2.4 | (2.0–2.9) | 1.31 | NS |

| Categoryb | ||||||||

| Circulatory system disorders | 70.7 | (69.2–72.1) | 77.0 | (73.5–80.1) | 69.8 | (68.2–71.3) | 7.19 | <0.001 |

| Mental and behavioral disorders | 64.9 | (63.2–66.5) | 65.4 | (61.5–69.1) | 64.8 | (63.1–66.5) | 0.58 | NS |

| Musculoskeletal or connective tissue disorders | 40.2 | (38.6–41.7) | 47.5 | (43.7–51.3) | 39.1 | (37.5–40.8) | 8.36 | <0.001 |

| Eye diseases | 11.3 | (10.4–12.3) | 11.2 | (9.1–13.8) | 11.3 | (10.4–12.3) | −0.07 | NS |

| Nervous system disorders | 11.3 | (10.5–12.2) | 9.5 | (7.6–11.8) | 11.6 | (10.7–12.5) | −2.1 | NS |

| Number of chronic health conditions | ||||||||

| 0 | 2.8 | (2.2–3.4) | 2.1 | (1.2–3.5) | 2.9 | (2.3–3.6) | −0.81 | NS |

| 1–3 | 56.3 | (54.7–57.9) | 43.5 | (39.7–47.4) | 58.1 | (56.4–59.8) | −14.64 | <0.001 |

| 4–6 | 34.4 | (33.0–35.9) | 41.8 | (38.2–45.5) | 33.4 | (31.8–35.0) | 8.43 | <0.001 |

| 7+ | 6.5 | (5.8–7.3) | 12.6 | (10.4–15.2) | 5.6 | (4.9–6.4) | 7.02 | <0.001 |

| Mean (SE) | 3.34 | (0.04) | 3.97 | (0.09) | 3.25 | (0.04) | 0.72 | <0.001 |

Weighted percentage and 95% confidence interval. Prevalence estimates for paralysis, spinal cord injury, traumatic brain injury, muscular dystrophy, and cerebral palsy are not reported due to lack of reliability (cell size < 30).

Circulatory system disorders: congestive heart failure; coronary heart disease; heart attack or myocardial infarction; high blood pressure or hypertension; stroke; other heart condition or heart disease.

Mental and behavioral disorders: Alzheimer’s disease or other dementia; depression; intellectual or developmental disabilities; serious mental problems (e.g. schizophrenia or psychosis); other mental, emotional, or nervous conditions.

Musculoskeletal or connective tissue disorders: arthritis or rheumatoid arthritis; gout, lupus, or fibromyalgia; osteoporosis.

Eye diseases: glaucoma, macular degeneration.

Nervous system disorders: nervous system disorders including multiple sclerosis, Parkinson’s disease, and epilepsy; partial or total paralysis; spinal cord injury; traumatic brain injury; cerebral palsy; muscular dystrophy.

Among residents without a given chronic condition, COPD was associated with a higher age-adjusted prevalence of having visited a hospital emergency room in the previous 12 months (Table 4) and of having an overnight hospital stay in the previous 12 months (Table 5). Among residents with a given chronic condition, COPD was associated with a higher age-adjusted prevalence of having visited a hospital emergency room (Table 4) if they had hypertension (45.0% vs. 36.2%), depression (49.5% vs. 38.1%), osteoporosis (47.7% vs. 35.2%), diabetes (46.3% vs. 37.2%), congestive heart failure (54.2% vs. 42.8%), or asthma (53.7% vs. 38.5%), and of having stayed in a hospital overnight (Table 5) for hypertension (31.0% vs. 24.7%), depression (38.4% vs. 26.4%), arthritis (31.5% vs. 24.2%), osteoporosis (35.6% vs. 24.4%), other mental, emotional, or nervous condition (38.3% vs. 27.8%), cancer (42.2% vs. 26.6%), or nervous system disorders (44.5% vs. 26.4%).

Table 4.

Prevalence of at least one hospital emergency room visit in previous 12 months by COPD and chronic condition status-NSRCF 2010

| Comorbidity/chronic health condition | Chronic condition absent | p-value | Chronic condition present | p-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No COPD %a (95% CI) |

COPD % (95% CI) |

COPD vs No COPD | No COPD % (95% CI) |

COPD % (95% CI) |

COPD vs No COPD | |

| High blood pressure/hypertension | 29.7 (27.6–31.8) | 38.9 (32.8–45.4) | 0.0060 | 36.2 (34.3–38.1) | 45.0 (40.1–49.9) | 0.0012 |

| Alzheimer’s disease or other dementia | 32.3 (30.4–34.3) | 44.7 (39.8–49.8) | <0.0001 | 34.7 (32.5–36.9) | 38.2 (32.2–44.5) | NS |

| Depression | 31.6 (30.0–33.3) | 39.3 (34.7–44.1) | 0.0027 | 38.1 (35.4–40.9) | 49.5 (43.0–56.0) | 0.0016 |

| Arthritis or rheumatoid arthritis | 32.3 (30.7–34.0) | 43.0 (38.2–47.9) | <0.0001 | 36.2 (33.5–39.1) | 41.6 (35.4–48.0) | NS |

| Osteoporosis | 32.9 (31.3–34.6) | 41.0 (36.6–45.5) | 0.0008 | 35.2 (32.0–38.5) | 47.7 (39.7–55.9) | 0.0052 |

| Diabetes | 32.6 (31.1–34.2) | 41.2 (36.9–45.8) | 0.0003 | 37.2 (33.7–40.9) | 46.3 (38.7–54.0) | 0.036 |

| Other heart condition (not listed elsewhere) | 32.1 (30.5–33.7) | 41.8 (37.6–46.2) | <0.0001 | 41.1 (37.5–44.8) | 46.3 (36.6–56.3) | NS |

| Coronary heart disease | 32.1 (30.6–33.7) | 43.0 (38.7–47.4) | <0.0001 | 42.0 (37.8–46.3) | 40.4 (32.4–48.9) | NS |

| Congestive heart failure | 32.2 (30.6–33.8) | 38.3 (34.0–42.9) | 0.0096 | 42.8 (38.6–47.1) | 54.2 (46.4–61.7) | 0.0137 |

| Other mental, emotional, or nervous condition | 32.5 (31.0–34.1) | 41.4 (37.1–45.9) | 0.0002 | 39.9 (35.9–44.1) | 48.7 (39.9–57.6) | NS |

| Stroke | 32.6 (31.1–34.2) | 41.9 (37.7–46.1) | 0.0001 | 39.6 (35.4–44.0) | 46.9 (36.6–57.5) | NS |

| Cancer or malignant neoplasm of any kind | 33.3 (31.7–34.8) | 42.5 (38.5–46.7) | <0.0001 | 34.2 (29.9–38.9) | 42.3 (31.6–53.8) | NS |

| Anemia | 32.5 (31.0–34.1) | 41.6 (37.5–45.9) | 0.0001 | 41.6 (37.0–46.4) | 48.2 (37.9–58.6) | NS |

| Nervous system disorders including multiple sclerosis, Parkinson’s disease, and epilepsy | 32.6 (31.1–34.1) | 41.7 (37.7–45.8) | <0.0001 | 42.7 (37.8–47.8) | 55.7 (41.2–69.3) | NS |

| Serious mental problems such as schizophrenia or psychosis | 33.5 (31.9–35.0) | 42.7 (38.5–46.9) | 0.0001 | 32.2 (27.7–37.0) | 41.1 (30.8–52.4) | NS |

| Gastrointestinal problems | 32.7 (31.2–34.2) | 42.2 (38.2–46.4) | <0.0001 | 41.8 (36.6–47.2) | 45.6 (33.7–58.0) | NS |

| Glaucoma | 33.1 (31.6–34.7) | 42.8 (38.8–46.9) | <0.0001 | 37.1 (31.7–42.8) | 37.4 (23.6–53.6) | NS |

| Macular degeneration | 33.5 (32.0–35.1) | 42.7 (38.7–46.8) | <0.0001 | 30.7 (25.5–36.4) | 39.9 (27.3–54.1) | NS |

| Kidney disease | 32.6 (31.1–34.1) | 42.3 (38.2–46.6) | <0.0001 | 47.2 (41.1–53.4) | 44.2 (32.7–56.4) | NS |

| Heart attack/myocardial infarction | 33.1 (31.6–34.6) | 42.1 (38.1–46.2) | <0.0001 | 40.7 (33.9–47.8) | 48.7 (34.5–63.2) | NS |

| Asthma | 33.2 (31.7–34.7) | 40.6 (36.5–44.8) | 0.0009 | 38.5 (30.8–46.9) | 53.7 (43.9–63.3) | 0.0171 |

| Intellectual or developmental disability such as mental retardation, severe autism, or Down syndromeb | 33.5 (32.0–35.0) | 42.4 (38.4–46.5) | 0.0001 | 30.2 (23.9–37.5) | 46.1 (29.8–63.3) | NS |

| Gout, lupus, or fibromyalgiab | 33.0 (31.5–34.5) | 41.7 (37.7–45.8) | 0.0001 | 49.4 (40.1–58.8) | 64.1 (46.1–78.8) | NS |

| Categoryc | ||||||

| Circulatory system disorders | 26.0 (23.7–28.5) | 33.4 (26.0–41.6) | NS | 36.5 (34.8–38.3) | 45.2 (40.9–49.7) | 0.0004 |

| Mental and behavioral disorders | 30.8 (28.3–33.4) | 39.7 (33.1–46.8) | 0.0155 | 34.8 (33.0–36.6) | 44.0 (39.5–48.6) | 0.0002 |

| Musculoskeletal or connective tissue disorders | 32.1 (30.3–34.0) | 39.9 (34.6–45.4) | 0.0068 | 35.3 (33.0–37.7) | 45.4 (39.9–51.1) | 0.0014 |

| Eye diseases | 33.4 (31.9–35.0) | 43.1 (39.0–47.3) | <0.0001 | 32.7 (28.8–36.8) | 37.9 (27.9–49.0) | NS |

| Nervous system disorders | 32.5 (30.9–34.0) | 41.8 (37.7–46.1) | <0.0001 | 40.2 (36.2–44.4) | 49.0 (38.0–60.1) | NS |

Weighted percentage and 95% confidence interval. Prevalence estimates for paralysis, spinal cord injury, traumatic brain injury, muscular dystrophy, and cerebral palsy are not reported due to lack of reliability (cell size < 30).

Prevalence estimates for gout, lupus, or fibromyalgia and intellectual or developmental disability may not be reliable (cell size 30–59).

Circulatory system disorders: congestive heart failure; coronary heart disease; heart attack or myocardial infarction; high blood pressure or hypertension; stroke; other heart condition or heart disease.

Mental and behavioral disorders: Alzheimer’s disease or other dementia; depression; intellectual or developmental disabilities; serious mental problems (e.g. schizophrenia or psychosis); other mental, emotional, or nervous conditions.

Musculoskeletal or connective tissue disorders: arthritis or rheumatoid arthritis; gout, lupus, or fibromyalgia; osteoporosis.

Eye diseases: glaucoma, macular degeneration.

Nervous system disorders: nervous system disorders including multiple sclerosis, Parkinson’s disease, and epilepsy; partial or total paralysis; spinal cord injury; traumatic brain injury; cerebral palsy; muscular dystrophy.

Table 5.

Prevalence of at least one overnight hospital stay in previous 12 months by COPD and chronic condition status-NSRCF 2010

| Comorbidity/chronic health condition | Chronic condition absent | p-value | Chronic condition present | p-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No COPD %a (95% CI) |

COPD % (95% CI) |

COPD vs No COPD | No COPD % (95% CI) |

COPD % (95% CI) |

COPD vs No COPD | |

| High blood pressure/hypertension | 20.1 (18.2–22.1) | 32.5 (26.9–38.8) | 0.0001 | 24.7 (23.1–26.5) | 31.0 (26.9–35.5) | 0.0073 |

| Alzheimer’s disease or other dementia | 22.8 (21.1–24.6) | 34.1 (29.9–38.7) | <0.0001 | 22.5 (20.6–24.5) | 26.7 (21.5–32.6) | NS |

| Depression | 21.4 (19.9–22.9) | 28.5 (24.6–32.8) | 0.0011 | 26.4 (24.0–28.8) | 38.4 (32.6–44.7) | 0.0003 |

| Arthritis or rheumatoid arthritis | 22.2 (20.7–23.7) | 31.7 (27.5–36.2) | <0.0001 | 24.2 (21.8–26.8) | 31.5 (26.1–37.4) | 0.0184 |

| Osteoporosis | 22.3 (20.8–23.8) | 30.5 (26.7–34.5) | 0.0001 | 24.4 (21.6–27.3) | 35.6 (28.2–43.9) | 0.0076 |

| Diabetes | 21.9 (20.5–23.4) | 31.4 (27.5–35.5) | <0.0001 | 26.7 (23.6–29.9) | 32.5 (25.7–40.1) | NS |

| Other heart condition (not listed elsewhere) | 21.6 (20.2–23.0) | 30.8 (27.2–34.6) | <0.0001 | 29.4 (26.0–33.0) | 36.3 (27.3–46.4) | NS |

| Coronary heart disease | 21.5 (20.1–22.9) | 31.7 (27.9–35.7) | <0.0001 | 31.3 (27.4–35.4) | 31.4 (24.1–39.7) | NS |

| Congestive heart failure | 21.1 (19.8–22.5) | 27.7 (24.1–31.7) | 0.0011 | 35.1 (31.1–39.2) | 42.5 (35.1–50.2) | NS |

| Other mental, emotional, or nervous condition | 22.0 (20.7–23.5) | 30.5 (26.8–34.4) | <0.0001 | 27.8 (24.3–31.7) | 38.3 (30.0–47.5) | 0.0326 |

| Stroke | 21.8 (20.5–23.2) | 31.6 (28.0–35.5) | <0.0001 | 29.9 (25.9–34.1) | 31.8 (22.7–42.6) | NS |

| Cancer or malignant neoplasm of any kind | 22.2 (20.9–23.6) | 30.3 (26.9–34.1) | <0.0001 | 26.6 (22.7–30.8) | 42.2 (31.4–53.7) | 0.0115 |

| Anemia | 22.1 (20.8–23.5) | 31.0 (27.4–34.8) | <0.0001 | 28.2 (24.1–32.8) | 35.9 (26.7–46.2) | NS |

| Nervous system disorders including multiple sclerosis, Parkinson’s disease, and epilepsy | 22.4 (21.1–23.8) | 30.8 (27.4–34.5) | <0.0001 | 26.4 (22.2–31.0) | 44.5 (31.1–58.8) | 0.0162 |

| Serious mental problems such as schizophrenia or psychosis | 22.6 (21.3–24.0) | 32.1 (28.5–36.0) | <0.0001 | 23.5 (19.5–28.0) | 27.6 (20.1–36.6) | NS |

| Gastrointestinal problems | 22.4 (21.0–23.7) | 31.3 (27.8–35.1) | <0.0001 | 27.0 (22.2–32.4) | 35.0 (24.1–47.8) | NS |

| Glaucoma | 22.4 (21.1–23.8) | 31.5 (28.0–35.2) | <0.0001 | 26.9 (22.0–32.4) | 34.1 (20.7–50.6) | NS |

| Macular degeneration | 22.7 (21.4–24.1) | 31.5 (28.0–35.3) | <0.0001 | 22.1 (17.6–27.3) | 33.5 (21.9–47.4) | NS |

| Kidney disease | 21.9 (20.6–23.3) | 31.3 (27.7–35.1) | <0.0001 | 37.3 (31.4–43.7) | 34.8 (24.3–47.1) | NS |

| Heart attack/myocardial infarction | 22.2 (20.9–23.5) | 31.5 (28.1–35.2) | <0.0001 | 35.9 (29.3–43.1) | 33.2 (21.3–47.8) | NS |

| Asthma | 22.6 (21.3–23.9) | 30.4 (26.8–34.2) | 0.0001 | 27.8 (20.7–36.2) | 39.1 (30.0–49.1) | NS |

| Intellectual or developmental disability such as mental retardation, severe autism, or Down syndromeb | 22.9 (21.6–24.3) | 31.7 (28.2–35.3) | <0.0001 | 16.4 (11.8–22.4) | 30.8 (17.4–48.5) | NS |

| Gout, lupus, or fibromyalgiab | 22.5 (21.2–23.9) | 30.9 (27.5–34.5) | <0.0001 | 30.5 (22.3–40.0) | 50.3 (33.2–67.4) | NS |

| Categoryc | ||||||

| Circulatory system disorders | 16.5 (14.5–18.7) | 24.9 (18.6–32.4) | 0.0227 | 25.4 (23.8–27.0) | 33.7 (29.7–37.8) | 0.0001 |

| Mental and behavioral disorders | 21.8 (19.6–24.1) | 31.4 (25.7–37.7) | 0.0027 | 23.2 (21.7–24.8) | 31.8 (27.9–35.9) | 0.0001 |

| Musculoskeletal or connective tissue disorders | 21.8 (20.2–23.6) | 28.9 (24.4–34.0) | 0.0054 | 24.0 (22.0–26.2) | 34.6 (29.6–40.0) | 0.0002 |

| Eye diseases | 22.5 (21.2–24.0) | 31.5 (27.9–35.3) | <0.0001 | 23.9 (20.5–27.7) | 32.9 (23.5–43.9) | NS |

| Nervous system disorders | 22.2 (20.9–23.6) | 30.6 (27.0–34.4) | <0.0001 | 26.5 (22.9–30.4) | 41.9 (31.6–52.9) | 0.0081 |

Weighted percentage and 95% confidence interval. Prevalence estimates for paralysis, spinal cord injury, traumatic brain injury, muscular dystrophy, and cerebral palsy are not reported due to lack of reliability (cell size < 30).

Prevalence estimates for gout, lupus, or fibromyalgia and intellectual or developmental disability may not be reliable (cell size 30–59).

Circulatory system disorders: congestive heart failure; coronary heart disease; heart attack or myocardial infarction; high blood pressure or hypertension; stroke; other heart condition or heart disease.

Mental and behavioral disorders: Alzheimer’s disease or other dementia; depression; intellectual or developmental disabilities; serious mental problems (e.g. schizophrenia or psychosis); other mental, emotional, or nervous conditions.

Musculoskeletal or connective tissue disorders: arthritis or rheumatoid arthritis; gout, lupus, or fibromyalgia; osteoporosis.

Eye diseases: glaucoma, macular degeneration.

Nervous system disorders: nervous system disorders including multiple sclerosis, Parkinson’s disease, and epilepsy; partial or total paralysis; spinal cord injury; traumatic brain injury; cerebral palsy; muscular dystrophy.

DISCUSSION

The prevalence of COPD for the RCF population was 12.4%, similar to the prevalence of self-reported physician diagnosed COPD among the noninstitutionalized US population aged 65 years and older (Ford et al., 2013). However, the COPD prevalence was higher among men compared to women, in contrast to estimates in the general population (Ford et al., 2013). Since the RCF population is older than the general population, this difference may reflect more men having a history of cigarette smoking compared to women in this older cohort (Burns et al., 1997). Women with are at a higher risk of hospitalization and death from COPD than are men (Ohar, Fromer, & Donohue, 2011). Fewer women with COPD may be living long enough to be represented in the RCFs. They may also require more care than is normally provided by RCFs. The prevalence was lowest among residents aged 85 years or older (10.3%). No differences in COPD prevalence were found by race/ethnicity or level of education, but it was less common among married individuals compared to those who were separated or divorced or had never married or were widowed. This observation supports the frequently-found association between being married and better health (Schoenborn, 2004) and is similar to the pattern found in the general population (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2012; Ford et al., 2013). In addition to different study populations, it should be noted that these surveys of the general population (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2012; Ford et al., 2013) relied on self-reports of physician-diagnosed COPD in contrast to the NSRCF’s use of medical records. This methodological difference could also contribute to discrepancies in prevalence estimates.

Comorbidities are common among patients with COPD (Garcia-Olmos et al., 2013; Mapel et al., 2000). Residents with COPD had a significantly higher mean of 4 chronic conditions (in addition to COPD), compared to only 3.25 chronic conditions for residents without COPD. In addition, various studies have observed higher rates of individual chronic conditions among persons with COPD than among those without COPD including cardiovascular disease (Feary et al., 2010; Lindberg et al., 2011; Sin & Man, 2005) (coronary heart disease (Garcia-Olmos et al., 2013; Mapel et al., 2000; Schnell et al., 2012), congestive heart failure (CHF) (Garcia-Olmos et al., 2013; Mapel et al., 2000; Schnell et al., 2012), myocardial infarction (Garcia-Olmos et al., 2013; Mapel et al., 2000; Soriano et al., 2005)), hypertension (Lindberg et al., 2011), stroke (Feary et al., 2010; Lindberg et al., 2011; Schnell et al., 2012), diabetes (Feary et al., 2010), chronic kidney disease (Schnell et al., 2012), arthritis (Schnell et al., 2012), depression (Schnell et al., 2012), osteoporosis (Garcia-Olmos et al., 2013; Schnell et al., 2012; Soriano et al., 2005), cancer (Mapel et al., 2000; Schnell et al., 2012), ulcers/gastritis (Mapel et al., 2000), asthma (Garcia-Olmos et al., 2013), anemia (John et al., 2006), and visual impairment (Schnell et al., 2012; Soriano et al., 2005).

In this RCF population, compared to residents without COPD, residents with COPD were more likely to have the following conditions: coronary heart disease; a history of myocardial infarction; diabetes; kidney disease; arthritis; anemia; depression; serious mental problems such as schizophrenia or psychosis; and other mental, emotional, or nervous conditions. The difference in prevalence was especially pronounced for CHF (26.4% among those with COPD versus 11.3% among those without) and asthma (14.5% versus 2.7%). Other studies have observed a higher prevalence of CHF among individuals with COPD compared to those without (Garcia-Olmos et al., 2013; Mapel et al., 2000; Schnell et al., 2012). In a case-control study of a health maintenance population by Mapel and colleagues, 13.5% of patients with COPD had CHF, much higher than the prevalence among controls (2.5%) (Mapel et al., 2000). Among family practice patients in Madrid, the age and sex-adjusted prevalence ratio for CHF was 2.41 (8.03% versus 3.34%), the highest prevalence ratio for any of the chronic diseases included in the study (Garcia-Olmos et al., 2013). The difference was also dramatic in a cross-sectional study of the noninstitutionalized U.S. population (the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 1999–2008) with CHF prevalence of 12.1% for participants reporting COPD versus 3.9% for those without (Schnell et al., 2012). Asthma and COPD are often reported together (Garcia-Olmos et al., 2013). Due to common symptoms and risk factors, it may be difficult for primary care physicians to differentiate between the two conditions. However, the existence of an overlap syndrome, in which both asthma and COPD are present, has been confirmed among older individuals (Marsh et al., 2008).

At the other end of the spectrum, Alzheimer’s disease or other dementia and nervous system disorders such as Parkinsons’s disease were less common among residents with COPD. Although little is known about the association of COPD with Alzheimer’s disease, many investigations into the association between smoking (the primary cause of COPD in the U.S.) and Alzheimer’s disease have been undertaken (Cataldo, Prochaska, & Glantz, 2010; Ferri et al., 2011; Garcia, Ramon-Bou, & Porta, 2010). Many cross-sectional studies have demonstrated an inverse relationship, which could be attributed to early mortality from smoking-related causes (Debanne, Bielefeld, Cheruvu, Fritsch, & Rowland, 2007), the potential effects of nicotine on dementia symptoms (Echeverria & Zeitlin, 2012), or the positive association of smoking with protective factors, such as coffee consumption (Lopez-Garcia et al., 2006; Nettleton, Follis, & Schabath, 2009). However, some investigators support the hypothesis that these results are largely indicative of bias (Cataldo et al., 2010; Debanne et al., 2007). Similarly, Parkinson’s disease and smoking have repeatedly been shown to be inversely related (Chen et al., 2010; Liu et al., 2012; Quik, Perez, & Bordia, 2012; Wirdefeldt, Adami, Cole, Trichopoulos, & Mandel, 2011).

COPD is an important cause of emergency department visits and hospitalization among adults in the U.S. (Buckelew, DeGood, Roberts, Butkovic, & MacKewn, 2009). In 2010, there were an estimated 1.5 million (72.0 per 10,000) emergency department visits and more than 699,000 (32.2 per 10,000) hospital visits among U.S. adults aged ≥25 years with COPD as the discharge diagnosis (Ford et al., 2013). In the same year, only 4% of all emergency department visits that resulted in hospital admissions for patients aged 65 years or older had COPD listed as the principal diagnosis, but nearly a quarter (23%) had COPD listed as any diagnosis (Buckelew et al., 2009). The corresponding estimates for all hospital stays were 3.3% with COPD listed as the principal diagnosis and 21% with COPD listed as any diagnosis (Buckelew et al., 2009). Several chronic health conditions associated with an increased rate of ER visits by RCF residents had an additional increase associated with COPD. These conditions (hypertension, depression, CHF, and diabetes) were common in the RCF population, with each condition having a prevalence of at least 10%; but, with the exception of hypertension, they were even more prevalent among residents with COPD. The same can be said of the following chronic health conditions associated with a higher prevalence of overnight hospital stays and also an additional COPD-associated increase: hypertension, depression, other mental, emotional, or nervous conditions, and cancer.

There are several actions RCF staff can take to improve care of their residents with COPD. A significant portion of COPD exacerbations that require hospitalization are due to pulmonary infections (Tsai, Clark, Cydulka, Rowe, & Camargo, 2007), stressing the importance of vaccination of individuals with COPD. The American Thoracic Society has recommended that COPD patients receive an annual influenza vaccine, as well as a pneumococcal vaccination at least once (American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society Task Force, 2004). In addition, RCF staff may be able to help prevent COPD exacerbations by improving residents’ medication adherence (Bourbeau, 2010). RCF staff may also be able to reduce hospitalizations by improving residents’ adherence to treatment for their comorbidities, such as hypertension, depression, diabetes, and congestive heart failure. Providing assistance with smoking cessation and promotion of physical activity would also be especially beneficial for COPD patients (American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society Task Force, 2004).

This study was subject to some limitations. The NSRCF relied on RCF staff for data on residents’ chronic disease history. Although the staff had access to residents’ records, it is possible that some information was overlooked or missing from these records. However, these data may also have been more reliable than residents’ self-reports would have been, especially for older residents suffering from dementia or other conditions that would impair memory or understanding of questions asked. Regarding data on hospital visits, the reason for these visits was not available. Therefore, although residents with COPD were more likely to visit hospital emergency rooms and have overnight hospital stays than those without COPD, these visits may not have been due to COPD, but to other conditions. Future research in this population would benefit from details about reasons for hospital visits, as well as information about vaccinations, and smoking policies at the facilities.

CONCLUSIONS

Chronic medical conditions are common among residents of RCFs with COPD. Residents with COPD are more likely to have specific conditions such as congestive heart failure and asthma than other residents and are also more likely to have had a visit to a hospital emergency room or overnight hospital stay in the previous year.

Footnotes

Disclosure Statement: The authors have no financial conflicts of interest to report.

Disclaimer: The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

References

- American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society Task Force. Standards for the diagnosis and management of patients with COPD. 2004 Retrieved from/z-wcorg/database Retrieved from http://www.thoracic.org/clinical/copd-guidelines/index.php.

- Barr RG, Celli BR, Mannino DM, Petty T, Rennard SI, Sciurba FC, Turino GM. Comorbidities, patient knowledge, and disease management in a national sample of patients with COPD. Am J Med. 2009;122(4):348–355. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2008.09.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourbeau J. Preventing hospitalization for COPD exacerbations. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2010;31(3):313–320. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1254071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckelew SP, DeGood DE, Roberts KD, Butkovic JD, MacKewn AS. Awake EEG disregulation in good compared to poor sleepers. Appl Psychophysiol Biofeedback. 2009;34(2):99–103. doi: 10.1007/s10484-009-9080-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burns DM, Lee L, Shen LZ, Gilpin E, Tolley HD, Vaughn J, Shanks TG. Cigarette smoking behavior in the United States. In: Shopland DR, Burns DM, Garfinkle L, Samet JM, editors. Changes in Cigarette-Related Disease Risks and Their Implication for Prevention and Control. Bethesda, MD: National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute; 1997. pp. 13–112. [Google Scholar]

- Caffrey C, Sengupta M, Park-Lee E, Moss A, Rosenoff E, Harris-Kojetin L. Residents living in residential care facilities: United States, 2010. NCHS Data Brief. 2012;(91):1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cataldo JK, Prochaska JJ, Glantz SA. Cigarette smoking is a risk factor for Alzheimer’s Disease: an analysis controlling for tobacco industry affiliation. J Alzheimers Dis. 2010;19(2):465–480. doi: 10.3233/jad-2010-1240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cazzola M, Bettoncelli G, Sessa E, Cricelli C, Biscione G. Prevalence of comorbidities in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Respiration. 2010;80(2):112–119. doi: 10.1159/000281880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Smoking-attributable mortality, years of potential life lost, and productivity losses--United States, 2000–2004. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2008;57(45):1226–1228. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease among adults--United States, 2011. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2012;61(46):938–943. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen H, Huang X, Guo X, Mailman RB, Park Y, Kamel F, Blair A. Smoking duration, intensity, and risk of Parkinson disease. Neurology. 2010;74(11):878–884. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181d55f38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Debanne SM, Bielefeld RA, Cheruvu VK, Fritsch T, Rowland DY. Alzheimer’s disease and smoking: bias in cohort studies. J Alzheimers Dis. 2007;11(3):313–321. doi: 10.3233/jad-2007-11308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Divo M, Cote C, de Torres JP, Casanova C, Marin JM, Pinto-Plata V, Celli B. Comorbidities and risk of mortality in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2012;186(2):155–161. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201201-0034OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Echeverria V, Zeitlin R. Cotinine: a potential new therapeutic agent against Alzheimer’s disease. CNS Neurosci Ther. 2012;18(7):517–523. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-5949.2012.00317.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feary JR, Rodrigues LC, Smith CJ, Hubbard RB, Gibson JE. Prevalence of major comorbidities in subjects with COPD and incidence of myocardial infarction and stroke: a comprehensive analysis using data from primary care. Thorax. 2010;65(11):956–962. doi: 10.1136/thx.2009.128082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferri CP, West R, Moriyama TS, Acosta D, Guerra M, Huang Y, Prince MJ. Tobacco use and dementia: evidence from the 1066 dementia population-based surveys in Latin America, China and India. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2011;26(11):1177–1185. doi: 10.1002/gps.2661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ford ES, Croft JB, Mannino DM, Wheaton AG, Zhang X, Giles WH. COPD surveillance-United States, 1999–2011. Chest. 2013;144(1):284–305. doi: 10.1378/chest.13-0809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Olmos L, Alberquilla A, Ayala V, Garcia-Sagredo P, Morales L, Carmona M, Monteagudo JL. Comorbidity in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in family practice: a cross sectional study. BMC Fam Pract. 2013;14:11. doi: 10.1186/1471-2296-14-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia AM, Ramon-Bou N, Porta M. Isolated and joint effects of tobacco and alcohol consumption on risk of Alzheimer’s disease. J Alzheimers Dis. 2010;20(2):577–586. doi: 10.3233/jad-2010-1399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- John M, Lange A, Hoernig S, Witt C, Anker SD. Prevalence of anemia in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: comparison to other chronic diseases. Int J Cardiol. 2006;111(3):365–370. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2005.07.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindberg A, Larsson LG, Ronmark E, Lundback B. Co-morbidity in mild-to-moderate COPD: comparison to normal and restrictive lung function. COPD. 2011;8(6):421–428. doi: 10.3109/15412555.2011.629858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu R, Guo X, Park Y, Huang X, Sinha R, Freedman ND, Chen H. Caffeine intake, smoking, and risk of Parkinson disease in men and women. Am J Epidemiol. 2012;175(11):1200–1207. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwr451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez-Garcia E, van Dam RM, Willett WC, Rimm EB, Manson JE, Stampfer MJ, Hu FB. Coffee consumption and coronary heart disease in men and women: a prospective cohort study. Circulation. 2006;113(17):2045–2053. doi: 10.1161/circulationaha.105.598664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mapel DW, Hurley JS, Frost FJ, Petersen HV, Picchi MA, Coultas DB. Health care utilization in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. A case-control study in a health maintenance organization. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160(17):2653–2658. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.17.2653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsh SE, Travers J, Weatherall M, Williams MV, Aldington S, Shirtcliffe PM, Beasley RW. Proportional classifications of COPD phenotypes. Thorax. 2008;63(9):761–767. doi: 10.1136/thx.2007.089193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moss AJ, Harris-Kojetin LD, Sengupta M, Park-Lee E, Caffrey C, Rosenoff E, Greene AM. Design and operation of the 2010 National Survey of Residential Care Facilities. Vital Health Stat. 2011;1(54) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nazir SA, Erbland ML. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: an update on diagnosis and management issues in older adults. Drugs Aging. 2009;26(10):813–831. doi: 10.2165/11316760-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nettleton JA, Follis JL, Schabath MB. Coffee intake, smoking, and pulmonary function in the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Study. Am J Epidemiol. 2009;169(12):1445–1453. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwp068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohar J, Fromer L, Donohue JF. Reconsidering sex-based stereotypes of COPD. Prim Care Respir J. 2011;20(4):370–378. doi: 10.4104/pcrj.2011.00070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quik M, Perez XA, Bordia T. Nicotine as a potential neuroprotective agent for Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord. 2012;27(8):947–957. doi: 10.1002/mds.25028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schnell K, Weiss CO, Lee T, Krishnan JA, Leff B, Wolff JL, Boyd C. The prevalence of clinically-relevant comorbid conditions in patients with physician-diagnosed COPD: a cross-sectional study using data from NHANES 1999–2008. BMC Pulm Med. 2012;12:26. doi: 10.1186/1471-2466-12-26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoenborn CA. Marital status and health: United States, 1999–2002. Adv Data. 2004;(351):1–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sin DD, Man SF. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a novel risk factor for cardiovascular disease. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 2005;83(1):8–13. doi: 10.1139/y04-116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soriano JB, Visick GT, Muellerova H, Payvandi N, Hansell AL. Patterns of comorbidities in newly diagnosed COPD and asthma in primary care. Chest. 2005;128(4):2099–2107. doi: 10.1378/chest.128.4.2099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai CL, Clark S, Cydulka RK, Rowe BH, Camargo CA., Jr Factors associated with hospital admission among emergency department patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease exacerbation. Acad Emerg Med. 2007;14(1):6–14. doi: 10.1197/j.aem.2006.07.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wirdefeldt K, Adami HO, Cole P, Trichopoulos D, Mandel J. Epidemiology and etiology of Parkinson’s disease: a review of the evidence. Eur J Epidemiol. 2011;26(Suppl 1):S1–58. doi: 10.1007/s10654-011-9581-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]