Abstract

Background:

Identifying occlusal status in a particular population will be valuable in planning the appropriate preventive and treatment programs. The purpose of this study was to assess the status of occlusion among school children in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Materials and Methods:

This study was conducted at Riyadh, Saudi Arabia from September 2012 to June 2013. A total of 1825 Saudis (1007 males and 818 females) of 12-16 years old were randomly selected from 20 schools in different areas of Riyadh city to determine the status of their occlusion. The examiners assessed molar and canine relationships, spacing and crowding, overjet, overbite, anterior and posterior cross bite. These occlusal parameters were examined by two experienced examiners using a mouth mirror, small light source and calibrated fiber ruler.

Results:

About 60.11% of Saudis presented with Class I molar relationship while 7.12% and 10.13% of the subjects had Class II and III molar relationship, respectively. The most prevalent canine relationship was Class I (54.13%), followed by Class II (12.4%) and Class III (11.2). Normal overjet and overbite were observed in 76% and 67% of the sample, respectively. The prevalence of malocclusion traits were crowding (45.4%), Spacing (26.9%), excessive over jet (16.4%), posterior cross bite (8.9%), anterior open bite (8.4%) and excessive overbite (6.68%). No statistically significant differences were found between the genders about the prevalence of any occlusion traits (P > 0.05).

Conclusion:

Class I molar relationship, normal overbite, and normal overjet were dominant features among Saudis. Crowding was the most prevalent malocclusion trait, followed by spacing. These findings will help in understanding the occlusion status in order to plan for prevention and treatment of malocclusion in Riyadh city.

Keywords: Children, malocclusion, molar relationship and canine relationship, occlusion

Introduction

Malocclusion is considered one of the most common dental problems together with dental caries, gingival disease, and dental fluorosis.1 Malocclusion may cause unpleasant appearance, impaired oral function, speech problems, tempromandibular disorders, increased susceptibility to trauma and periodontal disease.2 Identifying occlusal status in particular population provides important information on treatment needs and enables the government to draw the appropriate preventive and treatment programs.

Several studies investigated the prevalence of malocclusion in different population groups. The results of these studies revealed wide variations between those populations.3-13 These variations could be due to the differences in sample size, ethnicity, subjects’ age and registration methods. A number of studies have investigated the prevalence of malocclusion and treatment needs in Saudi Arabia. Al-Emran et al.6 reported that 62.4% of 500 male children had one or more malocclusion features related to dentition, occlusion, or space. About 40% were found to need treatment with fixed appliances. In addition, Nashashibi et al.14 found that 57.7% of the Saudi children required orthodontic treatment. In Abha city, Satheesh et al.15 reported that 42.8% of the evaluated subjects had a definitive degree of malocclusion. The characteristics of primary dentition occlusion in a group of Saudi children was investigated by Farsi and Salama16 who found that the Saudi children have less tendency for malocclusion during primary dentition than Caucasian populations.

In view of few prevalence studies on the occlusal status of a permanent dentition in Riyadh city, further investigation is indicated based on large population sample. Therefore, the aim of this study is to provide a description of the occlusal status of the permanent dentition among school children of 12-16 years old in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Materials and Methods

The current study was conducted at Riyadh, Saudi Arabia from September 2012 to June 2013. Twenty schools were randomly selected from the strata composite of different areas of Riyadh City (4 schools from north, 4 schools from south, 4 schools from east, 4schools from west and 4 schools from middle center of Riyadh). A total of 1,825 Saudis (1007 males and 818 females) aged 12-16 years were randomly selected and examined. The data were extracted from the original approved research (NF 2320) for which an ethical approval for human research was given by College of Dentistry Research Centre (CDRC), Deanship of Scientific Research. All the students were informed about their rights to participate in the study and consent forms were signed.

Students with a history of orthodontic treatment, systematic disease, craniofacial deformities or syndrome were not included in the sample. Clinical examination was carried out in the schools within the students’ classrooms by two experienced examiners using a mouth mirror, small light source and calibrated fiber ruler. The following parameters were recorded:

Molar relationship was scored for both right and left sides based on the angle classification system. Molar relation was recorded as Class I when the mesiobuccal cusp of the maxillary first permanent molar occluded with the mesiobuccal groove of the mandibular first permanent molar on both sides. A Class II or Class III molar relation was recorded when the mesiobuccal cusp of the maxillary first permanent molar occluded at least one-half cusp width anterior or posterior to the mesiobuccal groove of the mandibular first permanent molar on both sides, respectively. Asymmetric molar relationship was recorded when the right and left sides show different molar relationship.

Canine relationship was scored for both right and left side. Class I Canine relation was recorded when the tip of the maxillary canine occluded in the embrasure between the mandibular canine and first premolar tooth on both sides. A Class II or Class III canine relation was recorded when the tip of the maxillary canine occluded anterior or posterior to the embrasure between the mandibular canine and first premolar on both sides, respectively. Asymmetric canine relationship was recorded when the right and left sides show different canine relationship.

Spacing: It was recorded when the total spacing was at least 2 mm in a segment.

Crowding: It was recorded when the total sum of slipped contacts measured in the segment was at least 2 mm.

Overbite: The vertical overlap of incisors measured to the nearest half millimeter vertically from the incisal edge of the maxillary right central incisor to the incisal edge of the corresponding mandibular right incisor.

Overjet: It was measured with millimeter ruler as the distance from the most labial point of the incisal edge of the maxillary incisors to the most labial surface of the corresponding mandibular incisor.

Anterior open bite: It was recorded when there was no vertical overlap of the incisors, measured to the nearest half millimeter.

Anterior cross bite: It was recorded when one or more the maxillary incisors occluded lingual to the mandibular incisors.

Posterior cross bite: It was recorded when the buccal cusp of one or more of the maxillary posterior teeth occluded lingual to the buccal cusps of the opposing mandibular teeth.

Scissors bite: It was recorded when the lingual cusp of one or more of the maxillary posterior teeth occluded buccal to the buccal surfaces of the opposing mandibular teeth.

To ensure intra-examiner and inter-examiner reliability, the same examiner examined 20 children on two occasions with 1-week interval, and another 20 subjects were examined twice about 2 weeks apart by the two examiners. The intra-examiner correlation coefficient between the first and second scores ranging from 0.93 to 0.97 and weighted Kappa coefficient was found 0.81 and 0.87 respectively. The inter-examination reliability disclosed 93% agreement, and weight Kappa value was 0.83. These figures indicate a high level of agreement. Statistical analysis was performed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (Version 16.0; SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Simple descriptive statistics of occlusal parameters were reported. A Student’s t-test and one-way analysis of variance were used to examine differences in occlusal parameters relative to gender with a P < 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

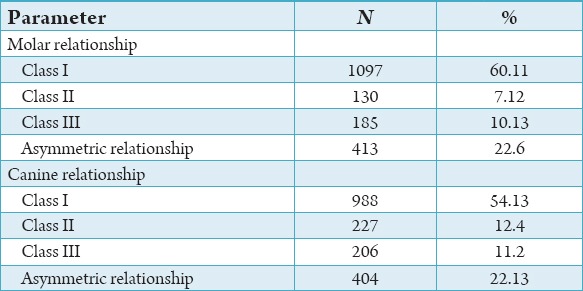

The study revealed no statistically significant differences found between the genders with regard to the prevalence of any occlusal traits (P > 0.05). Therefore, the data were analyzed without gender discrimination. Majority of subjects had symmetric molar relationship (77.4%) and symmetric canine relationship (78%), while about one-third of the sample presented with asymmetric molar and canine relationships. A symmetric Class I molar relationship was found in 60.11% of the subjects; Class II in 7.12% and Class III in 10.13%. The most prevalent canine relationship was symmetric Class I (54.13%), followed by symmetric Class II and Class III, which were observed in 12.4% and 11.2% of the sample, respectively (Table 1).

Table 1.

Prevalence of molar and canine relationships.

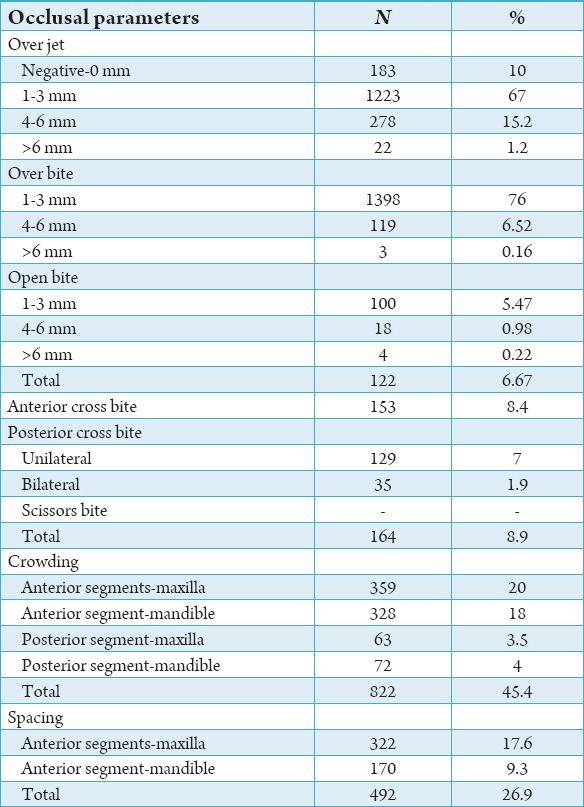

Table 2 explains the distribution of overjet, overbite, open bite, cross bite, spacing, and crowding in the study sample. 20% and 18% of the subjects had crowding in the anterior segments of the maxilla and the mandible, respectively. The results showed less crowding in the posterior segments with 3.5% of the sample in the maxilla and 4% in the mandible. On the other hand, 17.6% of the subjects had spacing in the anterior segment of the maxilla and 9% in the anterior segment of the mandible. The study showed that 10% of the subjects exhibited negative overjet or edge to edge relationship, 67% had overjet between 1-3 mm, 15% had overjet between 4-6 mm, and only 1.2% had overjet of more than 6 mm. Regarding overbite, The majority of the subjects (76%) had overbite with 1-3 mm overlap, while 6.52% showed 4-6 mm overlap and only 0.16% with more than 6 mm overbite. The result also indicated that 5.47% of the sample had open bite between 1 and 3 mm and only 18 subjects (0.98%) had open bite between 4 and 6 mm. 153 subjects (8.4%) presented with anterior cross bite while the unilateral and bilateral posterior cross bite were found in 129 subjects (7%) and 35 subjects (1.9%), respectively. Scissors bite was not observed in any subject participated in this study.

Table 2.

Distribution of over jet, over bite, open bite, cross bite, spacing, and crowding in the study sample.

Discussion

In the present descriptive study, a sample of 1825 subjects aged 12-16 year was examined to provide a description of the occlusion status of the permanent dentition in Riyadh population. 20 schools were randomly selected from the strata composite of different areas of Riyadh city (4 schools from north, 4 schools from south, 4 schools from east, 4schools from west and 4 schools from the center of city), to obtain a representative sample of Riyadh population. All subjects included in the study were in a permanent dentition stage. In addition, subjects with a history of orthodontic treatment, systematic disease, craniofacial deformities or syndrome were excluded from the sample. Mtaya et al.2 recommended that malocclusion prevalence studies should obtain a sample from a well-defined population and be large enough and cover subjects with no history of orthodontic treatment.

Numerous studies investigated the prevalence of malocclusion in various populations. The results of these studies revealed wide variations between those populations.3-13 Differences in the recording methods considered the most important factors explaining these variations.17 In the current study, Angle’s classification and canine relationship were used to evaluate sagittal occlusion. Angle’s classification is internationally recognized classification and widely used in the epidemiological study of malocclusion.18 In addition, spacing, crowding, overbite, overjet, anterior open bite, cross bite were recorded in this study to obtain detailed data on the status of occlusion vertically, horizontally, and within the dental arches.

The present study found 60.11% and 54.13% of Saudis in Riyadh city with Class I molar and canine relationships, respectively. There was a low prevalence of Class II and Class III molar and canine relationships. Among other population, several studies also reported predominance of Class I molar relationship either with the same low2,3,9,19 or higher8,20-22 prevalence of Class II and Class III molar relationship when compared with Saudis. The highest prevalence of Class I molar relationship among these studies was found in Tanzanians (93.6%),2 Nigerians (80.7), and Jordanians (79.8%).3

In the current study, the highest prevalence of crowding and spacing was found in maxillary anterior segment (20% and 17.6%, respectively). By comparing the prevalence of crowding to other malocclusal parameters, crowding was the most prevalent malocclusion trait and recorded in 45.4% of Saudis, followed by spacing (26.9%). This is in consistence with findings of other studies,6,8,17,23 which reported that crowding is the most common anomaly. The prevalence of crowding in Saudis was higher than the findings of Nigerians (12%)24 and Tanzanians (14.1%)2 but lower than the findings of Kuwaitis (69.5%)8 Jordanian (50%),3 and Pakistanis (57.2%),22 Brazilians (45.5%),19 Nepalese (65.7%),21 and Colombians (52.1%).17 67% and 76% of the subjects had normal overjet and overbite, respectively. Only 16.2% had excessive overjet, and 6.68% had a deep bite. High prevalence of normal overjet and overbite were also reported among Tanzanians (73.3% and 65.9%),2 Iranians (67.7% and 60.4%),9 Nigerians (68.3% and 81.8%),24 Pakistanis (58.4% and 61.4%).22 The results of the study show 6.67% of the subjects had anterior open bite, which is comparable to the findings for Nigerians,24 Iranians,20 Brazilians,19 Nepalese,21 and Colombians.17 The prevalence of anterior cross bite and posterior cross bite in the present study was 8.4% and 8.9%, respectively. This is in accordance with results reported by Nadim et al.22 among Pakistanis, Abu Alhaija et al.3 among Jordanians, Behbehani et al.8 among Kuwaitis, and Ajayi24 among Nigerians. On contrary, a higher prevalence of posterior cross bite was found among Iranians (36%),20 Nepalese (23.3%),21 and Brazilians (19.2%).19 These differences could be due to influences of variations in ethnicity, sample size or recording methods.

Conclusions

This study revealed predominance of Class I molar and canine relationships among Saudi School children in Riyadh city. Normal overjet and overbite were frequent findings. The most prevalent malocclusion trait was crowding followed by spacing. This study provides descriptive information for occlusion status that will be valuable in planning the appropriate preventive and treatment programs in the city.

Acknowledgments

Author would like to thank the CDRC and Deanship of Scientific Research at King Saud University, Saudi Arabia for funding this research project (research project # 2320).

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: None

Source of Support: Nil

References

- 1.Dhar V, Jain A, Van Dyke TE, Kohli A. Prevalence of gingival diseases, malocclusion and fluorosis in school-going children of rural areas in Udaipur district. J Indian Soc Pedod Prev Dent. 2007;25(2):103–5. doi: 10.4103/0970-4388.33458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mtaya M, Brudvik P, Astrøm AN. Prevalence of malocclusion and its relationship with socio-demographic factors, dental caries, and oral hygiene in 12- to 14-year-old Tanzanian schoolchildren. Eur J Orthod. 2009;31(5):467–76. doi: 10.1093/ejo/cjn125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Abu Alhaija ES, Al-Khateeb SN, Al-Nimri KS. Prevalence of malocclusion in 13-15 year-old North Jordanian school children. Community Dent Health. 2005;22(4):266–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Abu Alhaija ES, Qudeimat MA. Occlusion and tooth/arch dimensions in the primary dentition of preschool Jordanian children. Int J Paediatr Dent. 2003;13(4):230–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-263x.2003.00466.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aikins EA, Onyeaso CO. Prevalence of malocclusion and occlusal traits among adolescents and young adults in Rivers State, Nigeria. Odontostomatol Trop. 2014;37(145):5–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.al-Emran S, Wisth PJ, Böe OE. Prevalence of malocclusion and need for orthodontic treatment in Saudi Arabia. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 1990;18(5):253–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.1990.tb00070.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Anitha XL, Asokan S. Occlusion characteristics of preschoolers in Chennai: a cross-sectional study. J Dent Child (Chic) 2013;80(2):62–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Behbehani F, Artun J, Al-Jame B, Kerosuo H. Prevalence and severity of malocclusion in adolescent Kuwaitis. Med Princ Pract. 2005;14(6):390–5. doi: 10.1159/000088111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Borzabadi-Farahani A, Borzabadi-Farahani A, Eslamipour F. Malocclusion and occlusal traits in an urban Iranian population. An epidemiological study of 11- to 14-year-old children. Eur J Orthod. 2009;31(5):477–84. doi: 10.1093/ejo/cjp031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bourzgui F, Sebbar M, Hamza M, Lazrak L, Abidine Z, El Quars F. Prevalence of malocclusions and orthodontic treatment need in 8- to 12-year-old schoolchildren in Casablanca, Morocco. Prog Orthod. 2012;13(2):164–72. doi: 10.1016/j.pio.2011.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lux CJ, Dücker B, Pritsch M, Komposch G, Niekusch U. Occlusal status and prevalence of occlusal malocclusion traits among 9-year-old schoolchildren. Eur J Orthod. 2009;31(3):294–9. doi: 10.1093/ejo/cjn116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Onyeaso CO. Prevalence of malocclusion among adolescents in Ibadan, Nigeria. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2004;126(5):604–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2003.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Perinetti G, Cordella C, Pellegrini F, Esposito P. The prevalence of malocclusal traits and their correlations in mixed dentition children: results from the Italian OHSAR Survey. Oral Health Prev Dent. 2008;6(2):119–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nashashibi I, Darwish SK, Khalifa El R. Prevalence of malocclusion and treatment needs in Riyadh (Saudi Arabia) Odontostomatol Trop. 1983;6(4):209–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Haralur SB, Addas MK, Othman HI, Shah FK, El-Malki AI, Al-Qahtani MA. Prevalence of malocclusion, its association with occlusal interferences and temporomandibular disorders among the Saudi Sub-population. OHDM. 2014;13:164–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Farsi NM, Salama FS. Characteristics of primary dentition occlusion in a group of Saudi children. Int J Paediatr Dent. 1996;6(4):253–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-263x.1996.tb00254.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Thilander B, Pena L, Infante C, Parada SS, de Mayorga C. Prevalence of malocclusion and orthodontic treatment need in children and adolescents in Bogota, Colombia. An epidemiological study related to different stages of dental development. Eur J Orthod. 2001;23(2):153–67. doi: 10.1093/ejo/23.2.153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Houston WJ, Stephens CD, Tulley WJ. Great Britain: Wright; 1992. A Textbook of Orthodontics; pp. 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brito DI, Dias PF, Gleiser R. Prevalence of malocclusion in children aged 9 to 12 years old in the city of Nova Friburgo, Rio de Janeiro State, Brazil. R Dent Press Ortodon Ortop Facial. 2009;14:118–24. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Oshagh M, Ghaderi F, Pakshir HR, Baghmollai AM. Prevalence of malocclusions in school-age children attending the orthodontics department of Shiraz University of Medical Sciences. East Mediterr Health J. 2010;16:1245–50. doi: 10.26719/2010.16.12.1245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shrestha S, Shrestha RM. An analysis of malocclusion and occlusal characteristics in Nepalese orthodontic patients. Orthod J Nepal. 2013;3:19–25. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nadim R, Aslam K, Rizwan S. Frequency of malocclusion among 12-15 years old school children in three sectors of Karachi. Pak Oral Dent J. 2014;34:510–4. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Helm S. Malocclusion in Danish children with adolescent dentition: an epidemiologic study. Am J Orthod. 1968;54(5):352–66. doi: 10.1016/0002-9416(68)90304-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ajayi EO. Prevalence of malocclusion among school children in Benin City, Nigeria. JMBR. 2007;7:5–11. [Google Scholar]