Abstract

Background:

This in vitro study was conducted to compare the compression resistance of various interocclusal recording materials when subjected to a compressive load.

Materials and Methods:

Each interocclusal recording material was manipulated according to the manufacturer instruction and placed into a metallic cylinder. A total of 20 specimens for each interocclusal recording material were made. A total 100 specimens were fabricated. Each specimen was placed in the Universal Testing Machine exerting pressure on it, and a force of 100 g/cm2 was exerted on each sample. 30 s later the reading of the Universal Testing Machine was recorded using a vertical traveling micrometer microscope with an accuracy of ± 0.001 mm. This value was marked as reading “A.” 60 s after the application of the first force (100 g/cm2), a second force of 1000 g/cm2 was applied gradually during an interval of 10 s. 30 s later the reading of the Universal Testing Machine exerting pressure on the specimen was recorded again. This value was marked as reading “B.” The difference between readings “A” and “B” recorded the compression to resistance of each material. Comparisons within the groups and between the groups were done by using one-way ANOVA and Tukey’s HSD test.

Result:

There was significant variation between all interocclusal bite registration materials. According to the mean valve of each interocclusal bite registration material, Polyvinylsiloxane Bite Registration Material have better resistance to compression followed by Polyether interocclusal bite registration material, Aluwax Bite, and Impression Wax, Modeling Wax and at last Zinc Oxide Eugenol Impression Paste.

Conclusion:

Polyvinylsiloxane interocclusal registration material had the greatest resistance to compression. The least resistance to compression was noticed with zinc oxide-eugenol paste.

Keywords: Inter occlusion recording medium, Modeling Wax, polyvinylsiloxane, polyether, zinc oxide-eugenol paste

Introduction

Diagnosis and treatment of a patient for prosthetic rehabilitation requires the clinician to fabricate diagnostic casts as well as master casts and articulate them on an articulator. For this reason, it is necessary to record maxilla-mandibular relationship and accurately transfers it to the articulator.1 An interocclusal record is a precise recording of a maxillomandibular position.2

The material and technique used for making interocclusal records minimizes any intra-oral adjustment of the prosthesis. However, errors are often induced by the biologic characteristics of the stomatognathic system and by the dentist. To prevent clinical error, the procedure used to record, and fix interocclusal relations should be performed with the utmost care and understanding.3

Materials routinely used for registration of occlusal relationships are plaster, impression compound, wax, zinc oxide-eugenol paste, eugenol free zinc oxide paste, acrylic resin.4-6 Polyether and polyvinylsiloxane elastomeric materials are recently been introduced.7 Any dimensional changes in the records before articulation affects the vertical or horizontal interocclusal relationship requires more adjustment of the prosthesis in the mouth. The forces exerted on these records during removal from mouth or articulation depends on the thickness, properties of the material, the storage, the time interval between making the records, and articulation time affects these changes. Hence, the selection of interocclusal recording material is critical, depending on the situation.

This study has been undertaken to evaluate and compare the compressive resistance of five interocclusal recording materials. Such as Polyvinylsiloxane Bite Registration Crème, Polyether Bite Registration Material, Aluwax Bite and Impression Wax, Modeling Wax, and zinc oxide eugenol, impression paste.

Materials and Methods

A metallic cylinder with internal diameter 20 mm and 20 mm height were fabricated to standardize the specimens (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Metallic cylinders (internal diameter 20 mm and height 20 mm).

Grouping the specimen

Five commercially available interocclusal recording materials were used and the specimens were categorized into five groups of 20 specimen each:

Group I: Polyvinylsiloxane Bite Registration Crème (Exabite™ II NDS, GC America Inc.) was used.

Group II: Polyether Bite Registration Material (Rametac™, 3M ESPE Dental Products, U.S.A) was used.

Group III: Aluwax Bite and Impression Wax (Patented Aluwax Dental Products Company, U.S.A) was used.

Group IV: Modeling wax (Pyrex Polykem, Roorkee, India.) was used.

Group V: Zinc Oxide Eugenol Impression Paste (Dental Product of India [DPI]. A Division Of The Bombay Burmah Trading Corporation, Ltd., Mumbai, India) was used.

Manipulation of materials

All the materials were manipulated according to manufacturer’s instructions:

Waxes were softened in a hot water bath for 5 min and placed into the mold with the help of the glass syringe.

Polyether (Ramitec) and zinc oxide eugenol (DPI) were mixed on the glass slab and injected into the stainless steel mold.

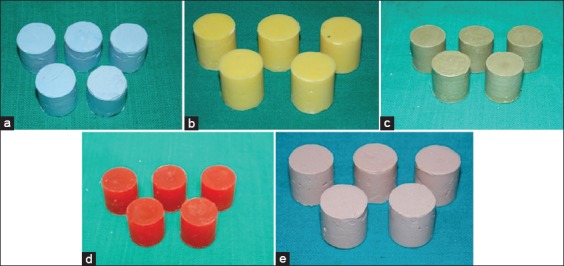

Polyvinylsiloxane (GC) was injected into the mold by dispensing gun (Figure 2a-e).

Figure 2.

Interocclusal recording material specimens with internal diameter 20 mm and height 20 mm. (a) Samples of Polyvinyl Siloxane Bite Registration Crème. (b) Samples of Polyether Bite Registration Material. (c) Samples of Aluwax Bite and Impression Wax. (d) Samples of Modeling Wax. (e) Samples of Zinc Oxide Eugenol Impression Paste.

Specimen fabrication

All materials were stored according to manufacturer instructions. Testing of the resistance to compression after setting was performed following a modification of the method described in A.D.A. specification No. 19 for the elastomeric impression materials. One cylindrical stainless steel mold with an internal diameter of 20 mm and a height of 20 mm was constructed.

The method described for the testing of the elastomeric materials was also applied for the testing of the waxes and the zinc oxide–eugenol impression paste. This was done in order to compare the results of all the materials included in this study.

The walls of the metallic cylinders (stainless steel mold) walls were lubricated with petroleum jelly before the placement of the elastomeric bite registration like polyvinylsiloxane, polyether, rigid material like Zinc Oxide Eugenol Impression Paste, Aluwax, and Modeling Wax to facilitate easy removal of the specimen from the cylinder.

Interocclusal registration materials were mixed according to the manufacturers’ instructions and were then injected into the mold, which was resting on a glass plate. A second glass plate was placed on top of it, and hand pressure was applied for 5 s to initially express material; this was followed by application of a 0.5 kg weight to further eliminate excess material.

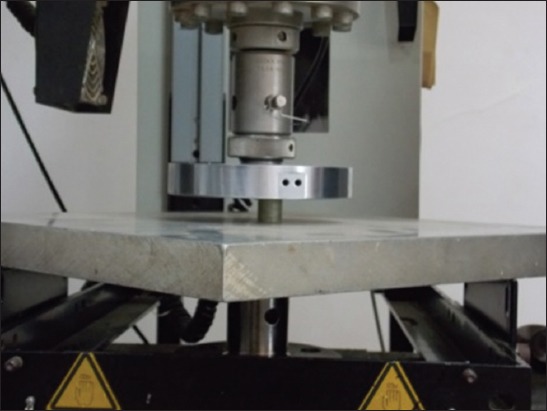

For the waxes, the method was modified by softening it and submerged in a water bath at 45°C. Afterward, a 10 ml syringe was filled with the wax and was placed in the water bath for 5 min. After this period, the wax was injected into the mold, which was standing on the glass plate. To simulate oral conditions the molds were submerged in a 36 ± 1°C water bath according to the manufacturer’s recommendations until the material sets.4 6 min after its removal from the water bath and from the mold, each specimen was placed in a Universal Testing Machine for exerting pressure on it, a force of 100 g/cm2 was exerted on each sample (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Specimen under testing in Universal Testing Machine.

30 s later, the reading of the pressing instrument was recorded using a vertical traveling micrometer microscope with an accuracy of ± 0.0019 mm (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Vertical traveling micrometer microscope.

This value was marked as reading “A.” 60 s after the application of the first force (100 g/cm2), a second force of 1000 g/cm2 was applied gradually during an interval of 10 s. 30 s later the reading of the Universal Testing Machine on the specimen was recorded again. This value was marked as reading “B.” The difference between readings “A” and “B” recorded the compression to resistance of each material.

Testing of the specimens

The Universal Testing Machine was used to apply the compressive force of 20 N for all the specimen.

The deformation of each specimen was measured after 30 s of loading and compared by means of appropriate statistical analyses.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive data included mean, standard deviation, coefficient of variation, and range values were calculated for each of the groups. Comparisons between the groups and within the groups were done by applying one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s HSD test. P < 0.05 was considered for statistical significance.

Results

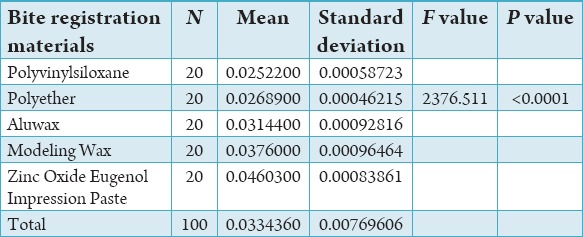

There is significant variation between all bite registration materials in 100 g/cm2 and 1000 g/cm2 (P < 0.005).

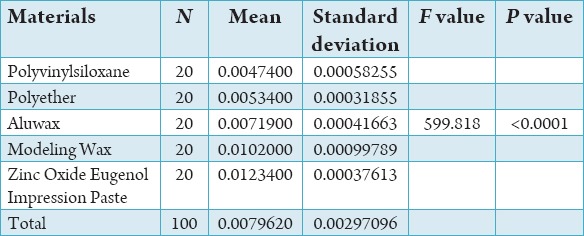

Table 1 shows mean and standard deviation of the distribution of force in various bite registration materials.

Table 1.

Mean and standard deviation of distribution of force in various bite registration materials.

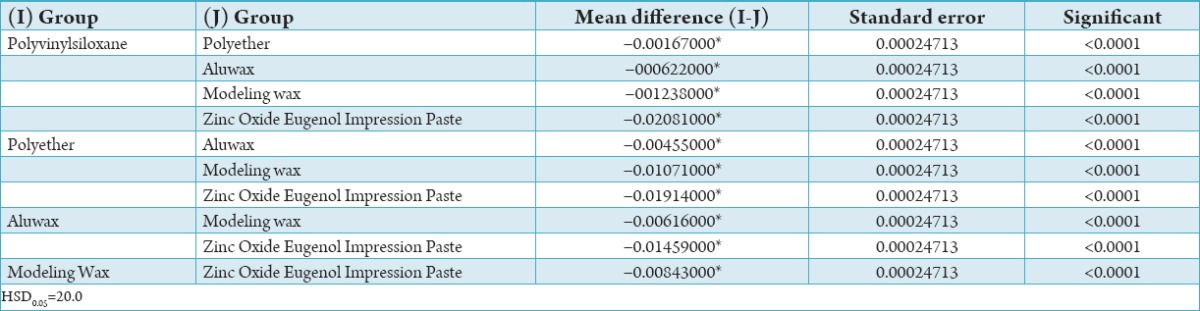

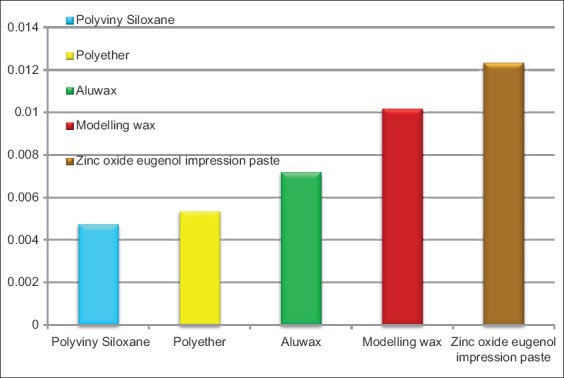

In pair-wise comparison there was significant variation between all interocclusal bite registration materials and as per mean of each interocclusal bite registration material, Polyvinylsiloxane Bite Registration Material have better resistance to compression followed by Polyether interocclusal bite registration material, Aluwax Bite and Impression Wax, Modeling Wax and, at last Zinc Oxide Eugenol Impression Paste (Table 2).

Table 2.

Tukey HSD to compare the resistance of compression of 5 material.

One-way ANOVA revealed the significant differences among the materials tested (F = 599.81, P < 0.0001) (Table 3).

Table 3.

One-way ANOVA for the evaluation of resistance to compression with 5 materials.

This test revealed that compared to the rest of the interocclusal recording media tested, polyvinylsiloxane interocclusal registration material had the greatest resistance to compression. Zinc oxide-eugenol paste was the material with the least resistance to compression (Graph 1).

Graph 1.

Distribution of resistance to compression in various bite registration materials.

Discussion

Recording maxillomandibular relationships is an important step in oral rehabilitation. This relationship is transferred to the articulator, so that the laboratory procedures done on the casts will correspond with the patient’s mouth. Various methods of recording maxillomandibular relationships like graphic, functional, cephalometric, and direct interocclusal can be used.8

Direct interocclusal records are commonly used to record maxillomandibular relationships. The recording material, which is soft initially fills the spaces between teeth, hardens, and records the specific relationship of the arches. The set material is then transferred onto casts to be mounted on an articulator.9

According to Millstein and Hsu, the interocclusal record should be an accurate and dimensionally stable representation of an interocclusal space that is subsequently transferred to an articulator.10

The first interocclusal registration was made in 1756 by Philip Pfaff.1 Plaster, wax, modeling compound, zinc oxide-eugenol paste, auto polymerizing acrylic resin, condensation type silicones, polyether, and polyvinylsiloxane are the commonly used materials for recording maxillomandibular relationship.9

The ideal properties of the interocclusal registration medium are:

Limited initial resistance to closure (in order to avoid the displacement of mobile teeth or of the mandible during record making).

Dimensional stability after setting.

Resistance to compression after polymerization.

Ease of manipulation.

Should not have any adverse effects on the tissues.

Accurately record the incisal or occlusal surfaces of the teeth.

Ease of verification.1

The importance of accurate, reliable recordings of jaw relations cannot be over emphasized. The function of indirectly made crowns and fixed partial dentures is directly related to this critical step.11 Proper interocclusal records minimizes pre-insertion adjustments to the restorations and saves chair side time or repetition of some clinical and technical stages.1

The most desirable characteristics of the interocclusal registration materials is resistance to compression after polymerization. The material should be rigid enough to resist the distortion that might be caused from the weight of the dental casts, the components of the articulator, or other means used to stabilize the casts during the mounting procedure.12 The resistance to compressive forces is very important because restorative errors occurs due to the discrepancy between the intra-oral relationships of the teeth and the position of the teeth on the mounted working cast.13

This in vitro study was conducted with the objective to compare the compressive resistance of five different interocclusal recording materials when subjected to a compressive load.

In the present study, 20 specimens of each material were fabricated. Each specimen was submerged in a 36 ± 1°C water bath, to simulate mouth conditions. Each specimen was left in the bath for the manufacturer’s suggested setting time plus an additional 3 min. 6 min after its removal from the water bath and from the mold, each specimen was placed in an Universal Testing Machine exerting pressure on it, and a force of 100 g/cm2 was exerted on each sample. 30 s later the reading of the pressing instrument was recorded using a vertical traveling micrometer microscope with an accuracy of ± 0.001 mm.12

This value was marked as reading “A.” 60 s after the application of the first force (100 g/cm2), a second force of 1000 g/cm2 was applied gradually during an interval of 10 s. 30 s later the reading of the instrument exerting pressure on the specimen was recorded again this value was marked as reading B.12

Among the specimens, Polyvinylsiloxane Bite Registration Material showed the least compression distance value (0.019 mm minimum - 0.026 mm maximum, mean at 100 g/cm2 = 0.020 and mean at 1000 g/cm2 = 0.025) than Ramitec Polyether Bite Registration Material (0.021 mm minimum - 0.027 mm maximum, mean at 100 g/cm2 = 0.021 and mean at 1000 g/cm2 = 0.026), Aluwax (0.023 mm minimum - 0.032 mm maximum, mean at 100 g/cm2 = 0.024 and mean at 1000 g/cm2 = 0.031), Modeling Wax (0.026 mm minimum - 0.038 mm maximum, mean at 100 g/cm2 = 0.027 and mean at 1000 g/cm2 = 0.037), and Zinc Oxide Eugenol Impression Paste (0.032 mm minimum - 0.047 mm maximum, mean at 100 g/cm2 = 0.033 and mean at 1000 g/cm2 = 0.046), respectively.

In this study, polyvinylsiloxane bite registration material showed greater resistance to compression than the other interocclusal recording materials. This observation was in correlation with the studies of Breeding and Dixon; Michalakis et al., who showed that polyvinylsiloxane displayed the greatest resistance to compression as compared to other elastomeric interocclusal recording materials, waxes, and a zinc oxide-eugenol paste.8,13

Craig and Sun observed that several bite registration elastomers had a desirable combination of high stiffness and low permanent deformation at the time of removal.14

Polyvinylsiloxane and Polyether Bite Registration Materials are characterized by short working time, setting time, high stiffness, low-percent strain in compression, and low flow.15 In this study, Polyvinylsiloxane bite registration material showed greater resistance to compression than Polyether Bite Registration Material. The reason for the greater compression resistance of polyvinylsiloxane bite registration material may be because of its low-dimensional change compared to Polyether Bite Registration Material.16

Studies done by Craig RG and Sun Z, Chai J, Tan E and Pang I C, Campos AA and Nathanson D have also shown that polyvinylsiloxane bite registration material was more accurate and dimensionally stable than Polyether Bite Registration Material.14,17

Zinc oxide-eugenol paste showed a decrease in compressive resistance when compared to other interocclusal recording materials. The reasons for the decreased compression resistance may be their lengthy setting time, significant brittleness, and loss of vital portions of the record through breakage.18

Wax showed a decrease in compressive resistance in specimens when compared to other interocclusal recording materials. There is general agreement that waxes, in any of the numerous forms available baseplate, Beauty hard wax, metallized or metallized with an aluminum laminate are the least accurate materials.19 Wax registrations can be distorted upon removal, may a change dimension by release of internal stresses depending on the storage condition, have high flow properties, undergo large dimensional changes on cooling from mouth to room temperature.16 Studies were done by Millstein et al.; Mullick et al.; Fattore et al., and Sindledecker have also shown that wax was the most variable and least reliable of all interocclusal recording materials.20-23

Therefore, if these interocclusal recordings are used for mounting working casts in the fabrication of the prostheses, the casts should be secured in a record in such a manner that ensures complete seating but exerts a minimal compressive force.

Limitation of the study

There was no simulation of intra-oral mouth temperature during the setting of the materials in this study. Further study is also needed to evaluate how much time after the maxillomandibular registration procedure the articulation of the cast should take place, also taking into account the dimensional stability of the materials.

Conclusion

Based on the observations of this study, the following conclusions were drawn:

Polyvinylsiloxane bite registration material displayed the greatest resistance to compression, when compared to polyether, Zinc Oxide Eugenol Impression Paste, Aluwax, and Modeling Wax.

Polyether interocclusal bite registration materials, with the exception of Polyvinylsiloxane, displayed greater resistance to compression than zinc oxide–eugenol impression paste, Aluwax, and Modeling Wax.

The material with the least resistance to compression after setting was zinc oxide-eugenol paste preceded by Aluwax and Modeling wax.

The order of resistance to compression of interocclusal bite registration materials in this study is as follows:

Polyvinylsiloxane > Polyether > Aluwax > Modeling Wax > Zinc Oxide Eugenol Impression Paste.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: None

Source of Support: Nil

References

- 1.Michalakis KX, Pissiotis A, Anastasiadou V, Kapari D. An experimental study on particular physical properties of several interocclusal recording media. Part I: Consistency prior to setting. J Prosthodont. 2004;13(1):42–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-849X.2004.04005.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Millstein PL, Clark RE, Myerson RL. Differential accuracy of silicone-body interocclusal records and associated weight loss due to volatiles. J Prosthet Dent. 1975;33(6):649–54. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3913(75)80128-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Millstein PL. Accuracy of laminated wax interocclusal wafers. J Prosthet Dent. 1985;54(4):574–7. doi: 10.1016/0022-3913(85)90438-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Payne SH. Selective occlusion. J Prosthet Dent. 1955;5(3):301–4. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hickey JC. Centric relation. A must for complete dentures. Dent Clin North Am. 1964;8:587–600. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Trappozano VR. Occlusal record. J Prosthet Dent. 1955;5:325–32. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gupta S, Arora A, Sharma A, Singh KA. Comparative evaluation of linear dimensional change and compressive resistance of different interocclusal recording materials – An in vitro study. Indian J Dent Sci. 2013;5(4):32–7. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tripodakis AP, Vergos VK, Tsoutsos AG. Evaluation of the accuracy of interocclusal records in relation to two recording techniques. J Prosthet Dent. 1997;77(2):141–6. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3913(97)70227-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vergos VK, Tripodakis AP. Evaluation of vertical accuracy of interocclusal records. Int J Prosthodont. 2003;16(4):365–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Millstein PL, Hsu CC. Differential accuracy of elastomeric recording materials and associated weight change. J Prosthet Dent. 1994;71(4):400–3. doi: 10.1016/0022-3913(94)90103-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Müller J, Götz G, Hörz W, Kraft E. An experimental study on the influence of the derived casts on the accuracy of different recording materials. Part I: Plaster, impression compound, and wax. J Prosthet Dent. 1990;63(3):263–9. doi: 10.1016/0022-3913(90)90192-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Michalakis KX, Pissiotis A, Anastasiadou V, Kapari D. An experimental study on particular physical properties of several interocclusal recording media. Part III: Resistance to compression after setting. J Prosthodont. 2004;13(4):233–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-849X.2004.04038.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Breeding LC, Dixon DL. Compression resistance of four interocclusal recording materials. J Prosthet Dent. 1992;68(6):876–8. doi: 10.1016/0022-3913(92)90542-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dua MP, Gupta SH, Ramachandran S, Sandhu HS. Evaluation of four elastomeric interocclusal recording materials. Med J Armed Forces Indian. 2007;63(3):237–8. doi: 10.1016/S0377-1237(07)80143-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ockert-Eriksson G, Eriksson A, Lockowandt P, Eriksson O. Materials for interocclusal records and their ability to reproduce a 3-dimensional jaw relationship. Int J Prosthodont. 2000;13(2):152–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pae A, Lee H, Kim HS. Effect of temperature on the rheological properties of dental interocclusal recording materials. Korean-Austr Rheol J. 2008;20(4):221–6. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hatzi P, Tzakis M, Eliades G. Setting characteristics of vinyl-polysiloxane interocclusal recording materials. Dent Mater. 2012;28(7):783–91. doi: 10.1016/j.dental.2012.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Campos AA, Nathanson D. Compressibility of two polyvinyl siloxane interocclusal record materials and its effect on mounted cast relationships. J Prosthet Dent. 1999;82(4):456–61. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3913(99)70034-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Walls AW, Wassell RW, Steele JG. A comparison of two methods for locating the intercuspal position (ICP) whilst mounting casts on an articulator. J Oral Rehabil. 1991;18(1):43–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2842.1991.tb00028.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Millstein PL, Clark RE, Kronman JH. Determination of the accuracy of wax interocclusal registrations. II. J Prosthet Dent. 1973;29(1):40–5. doi: 10.1016/0022-3913(73)90137-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mullick SC, Stackhouse JA, Jr, Vincent GR. A study of interocclusal record materials. J Prosthet Dent. 1981;46(3):304–7. doi: 10.1016/0022-3913(81)90219-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fattore L, Malone WF, Sandrik JL, Mazur B, Hart T. Clinical evaluation of the accuracy of interocclusal recording materials. J Prosthet Dent. 1984;51(2):152–7. doi: 10.1016/0022-3913(84)90251-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sindledecker L. Effect of different centric relation registrations on the pantographic representation of centric relation. J Prosthet Dent. 1981;46(3):271–9. doi: 10.1016/0022-3913(81)90212-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]