Abstract

Aims

U.S. studies contribute heavily to the literature about the tax elasticity of demand for alcohol, and most U.S. studies have relied upon specific excise (volume-based) taxes for beer as a proxy for alcohol taxes. The purpose of this paper was to compare this conventional alcohol tax measure with more comprehensive tax measures (incorporating multiple tax and beverage types) in analyses of the relationship between alcohol taxes and adult binge drinking prevalence in U.S. states.

Design

Data on U.S. state excise, ad valorem and sales taxes from 2001 to 2010 were obtained from the Alcohol Policy Information System and other sources. For 510 state-year strata, we developed a series of weighted tax-per-drink measures that incorporated various combinations of tax and beverage types, and related these measures to state-level adult binge drinking prevalence data from the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System surveys.

Findings

In analyses pooled across all years, models using the combined tax measure explained approximately 20% of state binge drinking prevalence, and documented more negative tax elasticity (−0.09, P=0.02 versus −0.005, P=0.63) and price elasticity (−1.40, P<0.01 versus −0.76, P=0.15) compared with models using only the volume-based tax. In analyses stratified by year, the R-squares for models using the beer combined tax measure were stable across the study period (P=0.11), while the R-squares for models rely only on volume-based tax declined (P<0.01).

Conclusions

Compared with volume-based tax measures, combined tax measures (i.e. those incorporating volume-based tax and value-based taxes) yield substantial improvement in model fit and find more negative tax elasticity and price elasticity predicting adult binge drinking prevalence in U.S. states.

Keywords: Ad valorem tax, alcohol control, alcohol tax, binge drinking, elasticity, excise tax, harm reduction, prevention, tax structure

INTRODUCTION

Excessive alcohol consumption is a leading preventable cause of death and disability world-wide, and policies that influence the price of alcohol are among the most effective means of reducing excessive alcohol consumption and related harms [1–4]. Taxes are the most thoroughly researched alcohol pricing policy, and have strong evidence of effectiveness [1,5–7]. A tax on alcohol raises the price of alcoholic beverages, reducing economic availability and reducing consumption, which leads to reductions in adverse health and social outcomes related to alcohol consumption. Meta-analyses and systematic reviews find the price elasticity of demand for per capita alcohol consumption to be approximately −0.5 [5,7]. Although numerous studies have assessed the relationship between taxes and average (per capita) consumption, the effects of taxes on ‘heavy’ drinkers remains relatively controversial [8], and relatively few studies have assessed the relationship between alcohol taxes and binge drinking (i.e. drinking at or above levels associated with intoxication) [9]. Three studies from the 1990s used alcohol price data collected by the American Chamber of Commerce Research Associations (ACCRA) and reported price and binge drinking elasticity in the general population ranging from −0.29 to −1.29 [10–12].

U.S.-based studies contribute heavily to the world’s literature about the relationship between alcohol taxes and alcohol consumption, in part because the presence of 50 states with different alcohol taxes provided multiple opportunities for comparison. Studies of the effects of alcohol taxes vary in study design and include cross-sectional studies, quasi-experiments including ‘natural experiments’ that involve interrupted time–series design, longitudinal panel design and meta-analyses that synthesize tax effects on consumption. Despite the variation in study methodology, most alcohol tax studies in the United States have relied upon specific excise taxes (i.e. volume-based taxes, levied as a fixed $ amount per unit volume rather than a percentage of price) for beer as a convenient proxy measure for tax and/or the price of alcohol. This is due, in part, to the fact that volume-based taxes have historically been either the sole form of alcohol taxation or the predominant form of taxation based on their magnitude [5–7,13–16]. However, few states have increased volume-based taxes to keep pace with inflation. For example, since 1970 the average volume-based state beer tax has declined by approximately 70% in real terms [17].

Although all U.S. states apply volume-based taxes to all alcoholic beverages, 46 states and the District of Columbia also apply value-based taxes (i.e. taxes based on a percentage of price, rather than a fixed $ amount per unit volume). These value-based taxes include ad valorem excise taxes and sales taxes. Typically, ad valorem excise taxes are alcohol-specific and are applied at the wholesale or retail level prior to sale. Sales taxes, in general, are not specific to alcohol, and states vary regarding whether or not to apply them to alcohol purchases. Were value- and volume-based taxes highly correlated, relying upon volume-based taxes as the sole tax measure predicting drinking outcomes might not yield substantially different results compared with those accounting for all applied tax types. However, work by Klitzner showed that states applying ad valorem taxes have lower volume-based taxes [18].

Therefore, the failure to account for value-based taxes, particularly in light of the inflation-based erosion of volume-based taxes over time, suggests that measures relying solely upon volume-based taxes may be a poor proxy of alcohol taxes. This, in turn, could lead to inadequate characterization of the relationship between tax and alcohol-related consumption and related outcomes. Research on salience of tax types suggests that sales taxes which are applied to most goods, including alcohol beverages, have less of an effect on consumption than excise taxes [19]. However, because sales and ad valorem taxes paid by the consumers contribute to the final price, it is reasonable to expect that the inverse relationship between taxes and consumption over a long period (i.e. on an annual basis) is less susceptible to short-term behavioral responses to tax changes; therefore, the economic theory of demand may be more appropriate [20]. Because not all states applied sales tax and ad valorem tax to alcohol products, it is important to examine empirically whether the state variation of the combined tax measure can explain the difference of adult binge drinking, and to assess whether or not the magnitude of the association with adult binge drinking is stronger than that for the volume tax measure.

The convention of relying solely upon the beer tax reflects the fact that beer consumption accounts for more than half of ethanol consumed in the United States [21], and that there has been a high correlation between volume taxes for beer volume and those for wine and liquor [22]. The use of beer tax also reflects the ready availability of data for all states; comparable liquor and wine taxes are not applied in the 18 states that have monopoly control over wholesale and/or retail pricing and distribution system for those beverage types. However, after taking ad valorem excises and sale taxes into account, it is unknown whether there is a correlation among beverage-specific ad valorem taxes in states that apply them or whether beer, wine and liquor taxes are correlated. Therefore, it is important to compare a tax measure that relies upon beer taxes with a tax measure that incorporates taxes on beer, wine and liquor in predicting drinking outcomes.

The purpose of this research was to compare the conventional volume-based alcohol tax measure with combined tax measures (i.e. those incorporating additional tax and beverage types) in statistical models assessing the goodness-of-fit and strength of association between alcohol taxes and adult binge drinking prevalence in U.S. states. We hypothesized that the combined tax measure would predict binge drinking (i.e. improve model fit) more effectively compared with those based on the conventional beer volume-based tax measure.

METHODS

Tax data sources

State-level volume and ad valorem tax data for beer, wine and liquor in the United States from 2001 to 2010 were obtained from the Alcohol Policy Information System [22], developed and maintained by the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism(NIAAA). Sales tax data were obtained from the Tax Foundation [23]. Other data sources, such as the Federation of Tax Administrators and the National Alcoholic Beverage Control Association, were used to cross-check the accuracy of the data. Discrepancies were resolved by a public health lawyer using the legal research database WestlawNext. Tax policy data were collected and reviewed during the period from January 2011 to June 2013.

Because it is possible to calculate all applicable taxes on a per drink basis, the combined tax measure can be summed across applicable beverage types weighted by consumption patterns in the general population [21,24]. In the summation process, we assumed a tax pass-through rate of 1.0, largely reflecting the large heterogeneity of the estimates of pass-through in the literature and the lack of consensus [25,26].

The per-drink price basis for estimating the magnitude of ad valorem and sales taxes was based on average prices by beverage type (i.e. beer, wine and liquor) and drinking location (i.e. on-premises versus off-premises, where the price ratio is approximately 3 : 1) and data were obtained from the IMPACT Databank Review and Forecast [27,28]. Because some states imposed ad valorem taxes at the whole sale level, wholesale prices were assumed to be half of retail prices. These assumptions will be assessed for robustness in sensitivity analyses. The U.S. consumer price index was used to adjust alcohol prices for inflation.

Tax-per-drink measures

The weighted tax-per-drink by state and year was calculated by summing existing state-level volume taxes, sales taxes and ad valorem taxes, and weighting each component by the proportion of consumption based on beverage type and drinking location (i.e. on- versus off-premises). The ad valorem and sales taxes were first computed based on inflation-adjusted prices, and inflation-adjusted volume tax was added afterwards. Consumption proportions by beverage type (50% beer, 35% liquor, 15% wine) were based on data from the Alcohol Epidemiology Data System [21]. The ratio of off- to on-premises consumption was modeled at 3 : 1 [29]. Tax per drink based on multiple tax types for beer only was calculated in both license and control states. The average tax per drink based on combinations of tax and beverage types was calculated for license states. All taxes were converted into cents per U.S. standard drink (17.7 ml or 0.6 ounces of ethanol). From 2001 to 2010, 510 state-year strata were available for analysis in 50 U.S. states and the District of Columbia.

Drinking outcome

We extracted state-level binge drinking prevalence estimates for 2001 to 2010 from the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) surveys web interface of CDC. Binge drinking was defined as consuming ≥5 (men) or ≥4 (women) drinks during ≥1 occasions during the past 30 days. The BRFSS is a state-based random-digit-dial telephone survey of people aged ≥18 years which is conducted monthly in all states, the District of Columbia and three U.S. territories. Data were weighted to be representative of state populations. Extensive details about the BRFSS and its methods are available at www.cdc.gov/brfss.

State-level covariates

The non-tax policy score was constructed as part of an effort in developing an aggregate measure of the state alcohol policy environment [30]. The non-tax alcohol policy score was constructed based on summing the products between the rescaled efficacy rating (ER-1)/4 with implementation rating for each of the 28 non-tax alcohol policies [e.g. retail sales restriction, hours of sale, blood alcohol concentration (BAC) limit of 0.08, etc.] [31,32]. The state-level proportion of the population aged 21 years or above, gender, racial groups, level of urbanization and median household income were aggregated from the American Community Survey (http://www.census.gov/acs/www/). The religious adherence rate (Catholic) was obtained from the Association of Statisticians of American Religious Bodies (http://www.rcms2010.org/). The police officer rate was obtained based on data from the Bureau of Justice Statistics of the U.S. Department of Justices.

Analytical methods

Linear regression methods were used to examine the relationship between state-level alcohol tax measures and binge drinking prevalence. We used the R-square to evaluate the model goodness-of-fit and examined the proportion of outcome variance attributable to tax. In addition, we employed Generalized Estimating Equations (GEE) method to address the clustering among repeated measures of the same state over time and further adjust for the non-tax policy environment and other state-level demographics and socio-economic covariates, including age, gender, race/ethnicity, religious composition, median household income and police officers per capita [30]. We characterized the relationship between tax (price) and binge drinking prevalence in the forms of regression coefficient (beta), tax elasticity and price elasticity. The beta coefficient documented the change of state adult binge prevalence associated with 1 unit change (i.e. 1 cent) in the tax or price predictor, with robust standard errors accounting for clustering of repeated measures of the same states over time. Tax elasticity (percentage change in tax) was computed based on the coefficient multiplied by the ratio of average tax and average binge drinking prevalence. Similarly, we computed the tax-based price elasticity of binge drinking using a model employing price per drink as a predictor by incorporating a tax pass-through rate of 1.0.

Because the 18 states in the U.S. with a monopoly system on wine and/or liquor products do not have comparable taxes for those beverage types, we conducted separate analyses using all 50 states and Washington, DC to examine beer tax measures, and analyses using the 32 license states and Washington, DC to examine tax measures based on all beverage types.

RESULTS

Across 510 state-year strata, the average tax per drink based on beer volume tax only was 2.86 cents [standard deviation (SD)=2.57], and the tax per drink based on the beer combined tax was 10.84 cents (SD=4.67) (Table 1). The average binge drinking prevalence was 15.2% (SD=3.2%). Appendix 1 showed data of tax per drink measured by combinations of tax types and beverage types, and adult binge drinking prevalence for two medium-sized states. The correlation between the combined tax measure and the volume tax measure for beer among all states ranged from r=0.42 (P < 0.01) in 2001 to r=0.28 (P=0.05) in 2010, while the correlation between the combined tax measure and the volume tax measure for all beverages among the license states ranged from r=0.10 (P=0.57) in 2001 to r=−0.02 (P=0.90) in 2010. In 2001, the non-tax policy score was 3.87, SD=0.91 and ranged from 2.11 to 5.97, while in 2010 the score was 4.23, SD=0.86 and ranged from 2.43 to 6.74. The non-tax alcohol policy scores across all states increased slightly across all states during the study period (beta=0.04, P < 0.01); however, the non-tax policy score in 2001 was correlated highly with the non-tax policy score in 2010 (r=0.91, P < 0.01).

Table 1.

Average tax per drink, tax-based price per drink, adult binge drinking prevalence and state-level covariates, pooled from state-year strata from 2001 to 2010.

| Variable groups | Variable names | License states (n = 330) | All states (n = 510) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | ||

| Tax per drink (in cents) | Volume tax only, beer | 2.81 | 2.68 | 2.86 | 2.57 |

| Combined taxes, beer | 11.60 | 4.89 | 10.84 | 4.67 | |

| Volume tax only, all beverages | 3.73 | 2.41 | NA | NA | |

| Combined taxes, all beverages | 14.24 | 5.62 | NA | NA | |

| Price per drink (in cents) | Volume tax only, beer | 121.53 | 3.10 | 121.68 | 2.87 |

| Combined taxes, beer | 130.32 | 4.99 | 129.66 | 4.63 | |

| Volume tax only, all beverages | 143.91 | 2.95 | NA | NA | |

| Combined taxes, all beverages | 154.42 | 5.68 | NA | NA | |

| Drinking outcome | Adult binge drinking prevalence | 15.56% | 3.27% | 15.18% | 3.20% |

| State-level covariates | Non-tax policy score | 3.94 | 0.78 | 4.11 | 0.87 |

| Proportion of age 21 or above | 72.19% | 1.96% | 72.19% | 2.28% | |

| Male proportion | 48.42% | 0.98% | 48.47% | 0.92% | |

| Non-Hispanic white proportion | 74.83% | 15.99% | 78.57% | 14.86% | |

| Non-Hispanic black proportion | 9.85% | 10.44% | 8.84% | 10.13% | |

| Hispanic proportion | 6.77% | 7.90% | 5.50% | 6.72% | |

| Other race proportion | 8.45% | 10.94% | 7.01% | 9.14% | |

| Urban proportion | 97.96% | 2.43% | 97.9% | 2.24% | |

| Police officer rate per 1000 | 3.57 | 1.08 | 3.35 | 0.98 | |

| Religious adherence rate (Catholic) | 205.65 | 120.82 | 180.78 | 113.15 | |

| Median household income ($) | 47 454 | 7735 | 46 821 | 7770 | |

NA = not available; SD = standard deviation.

Table 2 shows the R-squares based on simple linear regression relating the various tax measures to adult binge drinking prevalence. Models using the combined tax measure (i.e. that incorporated all three tax types) had higher R-squares compared to models using the measure comprised solely of volume-based tax. Specifically, among all 50 states and DC in analysis across 10 years of pooled data, the percentage of variance explained (R-square) by the combined tax measure was 16 versus 6% for the volume-based tax measure. For beer taxes among license states, the percentage of variance explained by the combined tax measure was 24% versus 2% for the volume-based tax measure (see also Fig. 1). While incorporating additional tax types improved goodness-of-fit in statistical models, adding more beverage types did not improve goodness-of-fit (Fig. 1). For example, among license states, all taxes for beer explained 24% of binge drinking variance, while all taxes for all beverage types explained 22% (Table 2).

Table 2.

Percentage of variance of state binge prevalence explained by tax measures, by tax and beverage types included in the tax measures, United States, 2001–10.

| R-square, stratified by single selected yearsf |

Average R-square, multiple years |

P-value of trend test across 10 individual years |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| States | Predictors | 2001 | 2004 | 2007 | 2010 | 2001–05 | 2006–10 | 2001–10 |

| Licensea states | Volume tax only, beerb | 10% | 5% | 0% | 0% | 5% | 2% | 0.02 |

| Combined taxes, beerc | 24% | 25% | 25% | 34% | 24% | 25% | 0.99 | |

| Volume tax only, all beveragesd | 8% | 3% | 0% | 2% | 3% | 1% | 0.10 | |

| Combined taxes, all beveragese | 20% | 22% | 26% | 36% | 21% | 25% | 0.34 | |

| All statesa | Volume tax only, beer | 13% | 9% | 3% | 1% | 9% | 5% | <0.01 |

| Combined taxes, beer | 20% | 16% | 17% | 20% | 19% | 15% | 0.11 | |

License states include the 32 states and DC in which there is no state monopoly on wholesaling of either liquor or wine. Because the effective tax rates on monopolized beverages are unknown, analyses of all 50 states and DC pertain to beer, as only beer taxes data are available in all states.

Tax per drink (in cents) based on beer volume tax only.

Tax per drink (in cents) based on beer volume, sales and ad valorem taxes (i.e. beer combined taxes).

Tax per drink (in cents) based on volume tax only weighted by beer, wine, and liquor consumption (i.e. all beverages volume tax only).

Tax per drink (in cents) based on volume, sales and ad valorem taxes weighted by beer, wine and liquor consumption (i.e. all beverages combined taxes).

Analysis stratified by single select years is conducted, respectively, on n = 32 license states and DC, and on n = 51 all states.

Figure 1.

Percentage of variance (unadjusted R-square) of adult binge drinking prevalence explained by tax measures, by tax and beverage type, U.S. license states, 2010

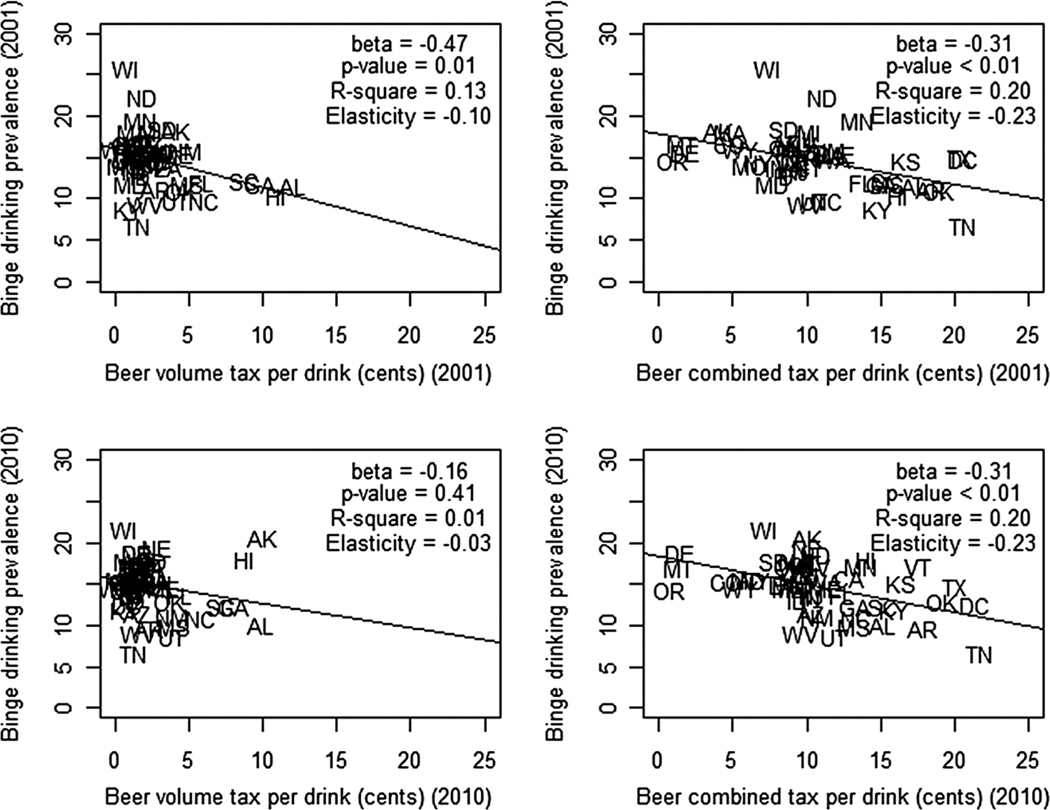

During the study period, models using volume-based tax measures experienced a progressive decline in goodness-of-fit (P < 0.01); by contrast, combined tax measures showed stable goodness-of-fit during the study period (P=0.11) (Table 2, Fig. 2). This was true when examining by individual years or 5-year time-periods. For example, for the beer volume tax measure among all states, the percentage of variance declined from 13% in 2001 to 1% in 2010, while the percentage of variance explained by the beer combined tax measure was 20% in both years. In addition, in 2010 the inverse relationship between tax and binge drinking was approximately twice as strong for the combined beer tax measure (beta=−0.31) compared with the volume-based tax measure (beta=−0.16). Similar findings were obtained with respect to tax elasticity estimates: for example, the elasticity for the combined tax measure for beer remained stable during the study period (e.g. −0.23 in 2001 versus −0.23 in 2010; see also Fig. 2), while the elasticity for the volume tax measure for beer decreased from −0.10 in 2001 to −0.03 in 2010.

Figure 2.

Scatterplots between beer volume tax and state binge prevalence versus between beer combined taxes and state binge prevalence, United States, 2001 versus 2010

There were significant inverse associations between the combined tax measure and state-level adult binge drinking in all models in Table 3; this was not the case for models using the volume-based tax measure. Furthermore, compared to models using volume-based tax measure, models using the combined tax measures resulted in more negative tax elasticity and more negative beta coefficients. For example, for the GEE-adjusted models of beer taxes in license states, the tax elasticity of demand was −0.14 for the combined tax measure compared with a non-significant tax elasticity using the volume-based tax measure. In terms of beta estimates from the adjusted GEE model among license states, a 1-cent increase in the beer tax measure that included all tax types was associated with a 0.19 percentage point decrease in binge drinking prevalence, compared with virtually no change for the measure based on volume taxes. The measure that included all tax types was significant in analyses stratified by study year and in models independent of the volume-based tax measure (data not shown).

Table 3.

Tax elasticity (percentage change) and regression coefficients (in cents) between alcohol tax and state binge drinking prevalence, by tax and beverage types included in the tax measures, United States, 2001–10.

| Bivariate GEE modelg | Adjusted GEE modelh | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| State-year strata | Predictor | Tax elasticitya | Beta | 95% CIs | P-value | Tax elasticity | Beta | 95% CIs | P-value |

| License statesb (n = 330) | Volume tax only, beerc | −0.02 | −0.12 | −0.39, 0.16 | 0.41 | 0.002 | 0.01 | −0.13, 0.14 | 0.92 |

| Combined taxes, beerd | −0.22 | −0.30 | −0.47, −0.13 | <0.01 | −0.14 | −0.19 | −0.31, −0.06 | <0.01 | |

| Volume tax only, all beveragese | −0.02 | −0.07 | −0.32, 0.18 | 0.57 | 0.005 | 0.02 | −0.11, 0.15 | 0.76 | |

| Combined taxes, all beveragesf | −0.24 | −0.25 | −0.39, −0.11 | <0.01 | −0.15 | −0.16 | −0.27, −0.05 | <0.01 | |

| All statesb (n = 510) | Beer volume tax only | −0.04 | −0.21 | −0.52, 0.09 | 0.17 | −0.005 | −0.03 | −0.14, 0.09 | 0.63 |

| Beer combined taxes | −0.16 | −0.23 | −0.37, −0.08 | <0.01 | −0.09 | −0.13 | −0.24, −0.02 | 0.02 | |

Elasticity (percentage change in tax) was computed based on beta*(mean tax per drink/mean binge prevalence). The average taxes per drink measured by beer volume tax only and by beer combined taxes were 2.9 cents and 10.8 cents among 50 states; the average taxes per drink measured by beverage volume tax only and by beverage combined taxes were 3.7 cents and 14.2 cents among 32 license states and DC. The average binge prevalence is 15%.

License states include the 32 states and DC in which there is no state monopoly on wholesaling of either liquor or wine. Because the effective tax rates on monopolized beverages are unknown, analyses of all 50 states and DC pertain to beer, as only beer taxes are available in all states.

Tax per drink (in cents) based on beer volume tax only.

Tax per drink (in cents) based on beer volume, sales and ad valorem taxes (i.e. beer combined taxes).

Tax per drink (in cents) based on volume tax only weighted by beer, wine, and liquor consumption (i.e. all beverages volume tax only).

Tax per drink (in cent) based on volume, sales and ad valorem taxes weighted by beer, wine and liquor consumption (i.e. all beverages combined taxes).

Each of the six Generalized Estimating Equations (GEE) regression models adjusted for clustering among repeated measures of states over the study period.

GEE regression models adjust for the non-tax policy environment and other state-level covariates including age, gender, race/ethnicity, religious composition, median household income, police officers per capita, year as categorical variable and clustering among repeated measures of states.

CI = confidence interval.

Because the tax elasticity of demand for binge drinking is readily interpretable only if one knows the relative magnitude of taxes versus base prices, and because price elasticity is a commonly used metric to assess effect of changes in prices and/or taxes, we also calculated the tax-based price elasticity for binge drinking assuming a tax pass-through rate of 1.0 (Table 4). Similar to findings for tax elasticity in Table 3, these combined tax measures yielded more negative price elasticity and more negative beta estimates for binge drinking prevalence compared with those for conventional volume-based tax measures. For example, in the adjusted model among license states, the price elasticity for binge drinking based on the beer combined tax measure was −1.86, versus −0.47 for the measure based solely on the beer volume tax. Furthermore, while analyses based on the combined tax measures were significant, those based on volume tax measures were non-significant.

Table 4.

Price elasticitya (percentage change) and regression coefficients (in cents) between alcohol price and state binge drinking prevalence, by tax and beverage types included in the tax measures, United States, 2001–10.

| Bivariate GEE modelg | Adjusted GEE modelh | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| State-year strata | Predictor | Price elasticity | Beta | 95% CIs | P-value | Price elasticity | Beta | 95% CIs | P-value |

| License statesb (n = 330) | Volume tax only, beerc | −1.11 | −0.14 | −0.44, 0.15 | 0.34 | −0.47 | −0.06 | −0.19, 0.07 | 0.36 |

| Combined taxes, beerd | −2.63 | −0.31 | −0.49, −0.14 | <0.01 | −1.86 | −0.22 | −0.34, −0.10 | <0.01 | |

| Volume tax only, all beveragese | −1.01 | −0.11 | −0.39, 0.18 | 0.45 | −0.46 | −0.05 | −0.20, 0.09 | 0.45 | |

| Combined taxes, all beveragesf | −2.65 | −0.27 | −0.41, −0.12 | <0.01 | −1.82 | −0.18 | −0.29, −0.07 | <0.01 | |

| All statesb (n = 510) | Volume tax only, beer | −1.95 | −0.24 | −0.57, 0.08 | 0.14 | −0.76 | −0.10 | −0.23, 0.03 | 0.15 |

| Combined taxes, beer | −2.20 | −0.26 | −0.41, −0.10 | <0.01 | −1.40 | −0.16 | −0.28, −0.05 | <0.01 | |

Elasticity (percentage change in price based on a tax increase) was computed based on beta*(mean tax per drink/mean binge prevalence). Assuming 100% tax pass-through on the IMPACT Databank beverage prices with 10% reduction, among all states, the average price paid per drink of beer which includes beer volume tax is 122 cents, and the average price paid per drink of beer which includes beer combined taxes is 130 cents among all states. Among the 32 license states and DC, the average price per drink which includes volume tax for all beverages was 144 cents and the price per drink which includes all beverage and tax types was 154 cents. The average binge prevalence is 15%.

License states include the 32 states and DC in which there is no state monopoly on wholesaling of either liquor or wine (no state has a monopoly on beer). Because the effective tax rates on monopolized beverages are unknown, analyses of all 50 states and DC pertain to beer, as only beer taxes are available in all states.

Price with beer volume tax pass-through rate of 1.0.

Price with tax pass-through rate of 1.0 for beer volume, sales and ad valorem taxes (i.e. all taxes combined).

Price with tax pass-through rate of 1.0 for volume tax only weighted by beer, wine and liquor consumption (i.e. all beverages volume tax only).

Price with tax pass-through rate of 1.0 for volume, sales and ad valorem taxes weighted by beer, wine and liquor consumption (i.e. all beverages combined taxes).

Each of the six Generalized Estimating Equations (GEE) regression models adjusted for clustering among repeated measures of states over the study period.

Each of the six GEE regression models adjusted for the non-tax policy environment and other state-level covariates including age, gender, race/ethnicity, religious composition, median household income, police officers per capita, year as categorical variable and clustering among repeated measures of the states.

CI = confidence interval.

Regression results weighted by the inverse of the variation of the binge drinking prevalence yield similar conclusions. For example, the beta coefficient for the combined tax measure for beer on binge drinking among the license states was −0.19 (P=0.02) with the use of weights, while the beta was −0.19 (P < 0.01) without weights. Furthermore, we conducted a series of sensitivity analyses to evaluate alternative approaches for calculating the tax-per-drink measures and for relating them to binge drinking prevalence (Appendix 2). Overall, all these sensitivity analyses yielded similar model goodness-of-fit, suggesting robustness of the findings of the base models. These sensitivity analyses included: using wholesale to retail price ratio of 0.3 : 1 for on-premises and 0.7 : 1 for off-premises (compared with a ratio of 0.5 : 1 for both) to reflect possible wholesale to retail price differences specific to drinking locations; using an off- to on-premises consumption ratio of 4 : 1 (compared with 3 : 1); [29] assuming a 10%reduction in the IMPACT Databank estimates of the base prices; and using time-varying state-varying proportions of consumption by beverage type (compared with non-time- and state-varying proportions) [21].

Sensitivity analyses based on tax pass-through rates of 0.5 and 2.0 were used to determine tax-based price elasticity for binge drinking prevalence. Similar to findings in Table 4 (where a pass-through rate of 1.0 was used), all three models using the combined tax measure found significant negative associations between tax and binge drinking prevalence, while the three models using the volume-based tax measure found relatively fewer negative associations, none of which were statistically significant. For example, modeling a pass-through of 2.0 for the license state analysis for all beverage types, the combined tax measure yielded an tax-based price elasticity of −0.87, beta=−0.14, P < 0.01, whereas the volume-based tax measure yielded an elasticity of −0.09, beta=−0.01, P=0.76.

We conducted additional state fixed-effects models predicting binge prevalence. We found that based on a state fixed-effects model, the regression coefficients for the outcome of binge prevalence were −0.19 (P=0.07) for the combined tax measure for beer and −0.18 (P=0.06) for the combined tax measure for all beverages.

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, this is the first paper to systematically evaluate the relationship between comprehensive alcohol tax measures (i.e. those accounting for all volume- and value-based taxes) and binge drinking in the United States. In addition to demonstrating a robust inverse relationship between alcohol taxes and binge drinking, we found that more comprehensive tax measures resulted in substantially improved statistical models (on the basis of goodness-of-fit) to predict binge drinking outcomes compared with the conventional volume-based only tax measure, particularly in recent years.

In addition to improved validity, as suggested by the R-squares, using the comprehensive tax measures resulted in far more negative associations and elasticity estimates compared with those derived from the conventional volume-based tax measures. Although we were assessing binge drinking rather than average consumption, the plausibility of our findings is supported by the fact that our adjusted price elasticity estimates for binge drinking using the conventional volume-based tax measure was similar to that for alcohol consumption in published meta-analyses and systematic reviews (approximately −0.5) [5,7]. Although our findings pertain primarily to U.S. studies, given the large number of U.S.-based alcohol tax studies in the literature it is possible that the tax-based price elasticity of demand for alcohol—and therefore the effectiveness of taxes—may have been systematically underestimated.

The findings have important public health implications, because alcohol consumption is a leading preventable cause of mortality and morbidity, and of all policies taxes have the strongest evidence of reducing alcohol-related harms. Furthermore, binge drinking (i.e. drinking at or above levels that typically result in intoxication) is a fundamental behavioral manifestation for potential alcohol-related health and social problems [33]. Although taxes have been shown to decrease average consumption and alcohol-related harms, the degree to which taxes influence risky or heavy drinking patterns is less well informed by the literature.

Examining multiple tax types invites study of tax structure, or the relative composition of various tax types and related policies (e.g. minimum pricing) designed to raise the price of alcohol. Given the importance of alcohol taxes to public health and government revenue, it is surprising how little work has been conducted in understanding the impact of tax structure. This study demonstrates one vulnerability of volume-based specific excise taxes: their erosion over time due to inflation in the absence of regular increases or being indexed to inflation [34]. However, price increases affect both the quantity and quality (i.e. brand) of alcohol that is consumed [35]. Compared with volume-based taxes, value-based taxes impose larger absolute tax amounts on expensive brands and smaller absolute tax amounts on inexpensive brands. This results in relatively lower prices for inexpensive brands, and larger price differences between expensive and inexpensive brands than under a system that relies solely upon volume taxes. This can lead to increased substitution to lower-priced alcohol brands—and relatively smaller reductions in quantity consumed— compared with a system where all brands are taxed by an equal amount based on unit volume.

For tobacco, there is evidence that countries that rely on mixed tax structures have more smoking compared with countries that rely on specific taxes (i.e. based on a fixed amount per pack, which are comparable to volume-based taxes for alcohol) [36,37]. While volume-based tax increases raise relative prices more on lower-priced products compared with more expensive ones, minimum pricing policies take this a step further by putting a floor on the price of ethanol, limiting the degree to which one can maintain drinking quantity by shifting to progressively cheaper brands. Minimum pricing has a strong public health impact by targeting products and drinkers that cause disproportionate harm [38,39]. By affecting prices on a limited number of products, minimum prices may have a relatively small impact on total alcohol sales and consumer spending. Overall, however, mixed tax structures may be preferable, as was highlighted in a recent debate regarding the alcohol taxation system in Thailand [40], which resulted in an effective tax rate that imposed higher taxes on beverages preferred by heavy drinkers and beverages favored by youth.

This study is subject to caveats and limitations. We used national-level price data from IMPACT Databank Review and Forecast to calculate the approximate magnitude of state-level sales and ad valorem taxes because publicly available data on state-specific alcohol prices do not exist. In addition, we relied upon a number of evidence-grounded assumptions in constructing our models and these assumptions were assessed in sensitivity analyses. Some studies suggest that taxes are passed-through to prices at less than or greater than 1.0, with considerable variability in the pass-through estimates depending on the timing and context [25]. However, modeling different tax pass-through rates would have little impact on the findings for tax and price elasticity with respect to the relative differences between the various tax measures that were being compared, as confirmed in our sensitivity analyses.

Furthermore, as this study design relied upon cross-sectional survey data and included a limited set of state-level covariates, the findings are primarily associative in nature. However, previous longitudinal tax studies have established the temporal relationship between changes in taxes and subsequent changes in drinking-related outcomes, which have the advantage of accounting for cultural attitudes that led to the adoption of tax changes in the first place. It should be noted that the primary purpose of this paper was to assess how associations between alcohol taxes and binge drinking differed on the basis of how taxes are measured, rather than to establish a causal relationship between taxes and binge drinking. During a relatively short study period in which there is considerably more between-state difference than within-state tax changes, the GEE approach, which focuses upon the population averaged effect of state-level factors, can be appropriate for assessing the association between state alcohol taxes and state binge drinking prevalence when these models account for time fixed-effects and important state-level covariates. Nevertheless, state fixed-effects models address whether within-state changes of taxes can explain change of adult binge drinking prevalence and have the potential of controlling for unobserved confounding factors. Even though our analyses included only 10 years of data, the direction of the detected association between the combined tax measure and binge drinking prevalence was as expected and was marginally significant. When longer panels of tax data become available, it will be important to repeat state fixed-effects models [41].

In the future, the use of comprehensive state alcohol tax measure is warranted to re-examine the relationships between alcohol taxes and important drinking-related outcomes, including youth drinking, alcohol-impaired driving, alcohol-related violence and alcohol use disorders, and to determine whether or to what degree consensus estimates of tax effect may have been underestimated due to tax measurement limitations in many U.S.-based studies. From an international perspective, this study emphasizes the importance of assessing multiple tax types—and possibly tax structure—for characterizing the relationship between tax and related outcomes, evaluating the effects of tax policy interventions and for planning tax policy interventions.

Acknowledgements

This research is supported by National Institutes of Health grant number R01AA018377 (Principal Investigator: T.S. N.). The content and views expressed in this paper are those of the co-authors and do not necessarily represent those of the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism or the National Institutes of Health in the United States.

Footnotes

Declaration of interests

None.

Supporting information

Additional supporting information may be found in the online version of this article at the publisher’s web-site.

Appendix 1 Tax per drink (in cents)measured by combinations of tax types and beverage types, and adult binge drinking prevalence for two median size states.

Appendix 2 Sensitivity analyses on the relationship between alcohol taxes and binge drinking prevalence, United States, 2001–10.

References

- 1.Babor TF, Caetano R, Casswell S, Edwards G, Giesbrecht N, Graham K, et al. Alcohol: No Ordinary Commodity—Research and Public Policy. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Room R, Babor TF, Rehm J. Alcohol and public health. Lancet. 2005;365:519–530. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)17870-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Anderson P, Chrisholm D, Fuhr DC. Effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of policies and programmes to reduce the harm caused by alcohol. Lancet. 2009;373:223–246. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60744-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rehm J, Mathers C, Popova S, Thavorncharoensap M, Teerawattananon Y, Patra J. Global burden of disease and injury and economic cost attributable to alcohol use and alcohol-use disorders. Lancet. 2009;373:2223–2233. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60746-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wagenaar AC, Salois MJ, Komro KA. Effects of beverage alcohol price and tax levels on drinking: a meta-analysis of 1003 estimates from 112 studies. Addiction. 2009;104:179–190. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02438.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chaloupka FJ, Grossman M, Saffer H. The effects of price on alcohol consumption and alcohol-related problems. Alcohol Res Health. 2002;26:22–34. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Elder RW, Lawrence B, Ferguson A, Naimi TS, Brewer RD, Chattopadhyay SK, et al. Task Force on Community Preventive Services. The effectiveness of tax policy interventions for reducing excessive alcohol consumption and related harms. Am J Prev Med. 2010;38:217–229. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2009.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nelson JP. Does heavy drinking by adults respond to higher alcohol prices and taxes? A survey and assessment. [accessed 1 September 2013];Economic Analysis and Policy. 2013 Available at: http://www.eap-journal.com/archive/forthcoming/forthcoming_Jon_P._Nelson.pdf. (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/6Uo9csD5A) [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chaloupka FJ, Wechsler H. Binge drinking in college: the impact of price, availability, and alcohol control policies. Contemp Econ Policy. 1996;14:112–124. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Manning WG, Blumberg L, Moulton LH. The demand for alcohol: the differential response to price. J Health Econ. 1995;14:123–148. doi: 10.1016/0167-6296(94)00042-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kenkel DS. Drinking, driving, and deterrence: the effectiveness and social costs of alternative policies. J Law Econ. 1993;36:877–911. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kenkel DS. New estimates of the optimal tax on alcohol. Econ Inq. 1996;34:296–319. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Saffer J, Grossman M. Beer taxes, the legal drinking age, youth motor vehicle fatalities. J Legal Stud. 1987;16:351–374. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Laixuthai A, Chaloupka FJ. Youth alcohol use and public policy. Contemp Policy Issues. 1993;11:70–81. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Grossman M, Chaloupka FJ, Sirtalan I. An empirical analysis of alcohol addiction: results from the Monitoring the Future panels. Econ Inq. 1998;36:39–48. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cook PJ, Moore MJ. Environment and persistence in youthful drinking patterns. In: Gruber J, editor. Risky Behavior Among Youth: An Economic Perspective. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 2001. pp. 375–437. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Xu X, Chaloupka FJ. The effects of prices on alcohol use and its consequences. Alcohol Res Health. 2011;34:236–245. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Klitzner M. Improving the measurement of state alcohol taxes. [accessed 31 January 2012];NIAAA. 2012 Available at: http://alcoholpolicy.niaaa.nih.gov/improving_the_measurement_of_state_alcohol_taxes.html. (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/6Uo9o3sN8)

- 19.Chetty R, Looney A, Kroft K. Salience and taxation: theory and evidence. Am Econ Rev. 2009;99:1145–1177. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Marshall A. Principles of Economics. 8th edn. London: Macmillan; 1920. [Google Scholar]

- 21.LaVallee RA, Yi H. Surveillance Report no. 95: Apparent Per Capita Alcohol Consumption: National, State, And Regional Trends, 1977–2010. Rockville, MD: National Institute of Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, Division of Epidemiology and Prevention Research, Alcohol Epidemiologic Data System; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 22.National Institute of Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. [accessed 31 January 2012];Alcohol Policy Information System (APIS) 2012 Available at: www.alcoholpolicy.niaaa.nih.gov/. (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/6Uo9vWdPH)

- 23.The Tax Foundation. [accessed 31 July 2011];State sales, gasoline, cigarette, and alcohol tax rates by state, 2000–2010. 2010 Available at: http://taxfoundation.org:81/sites/taxfoundation.org/files/docs/state_various_sales_rates_2000-2010.pdf. (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/6UoA2O8NW) [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shang C, Chaloupka FJ, Zahra N, Fong GT. The distribution of cigarette prices under different tax structures: findings from the International Tobacco Control Policy Evaluation (ITC) Project. Tob Control. 2014;23:i23–i29. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2013-050966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Young DJ, Bielinska-Kwapisz A. Alcohol taxes and beverage prices. Natl Tax J. 2002;55:57–73. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kenkel DS. Are alcohol tax hikes fully passed through to prices? Evidence from Alaska. Am Econ Rev. 2005;95:273–277. [Google Scholar]

- 27.IMPACT Databank Review and Forecast. The U.S. Spirits, Wine and Beer Markets. New York: M. Shanken Communications; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Treno AJ, Gruenewald PJ, Wood DS, Ponicki WR. The price of alcohol: a consideration of contextual factors. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2006;30:1734–1742. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2006.00207.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Naimi TS, Nelson DE, Brewer RD. Driving after binge drinking. Am J Prev Med. 2009;37:314–320. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2009.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Naimi TS, Blanchette J, Nelson TF, Nguyen T, Oussayef N, Heeren TC, et al. A new scale of the U.S. alcohol policy environment and its relationship to binge drinking. Am J Prev Med. 2014;46:10–16. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2013.07.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Xuan Z, Blanchette JG, Nelson TF, Heeren TC, Oussayef N, Naimi TS. The alcohol policy environment and policy subgroups as predictors of binge drinking measures among US adults. Am J Public Health. 2014:e1–e7. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2014.302112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nelson TF, Xuan Z, Blanchette JG, Heeren TC, Naimi TS. Patterns of change in implementation of state alcohol control policies in the United States, 1999–2011. Addiction. 2014 doi: 10.1111/add.12706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Naimi TS, Brewer RD, Mokdad AH, Denny C, Serdula M, Marks JS. Binge drinking among U.S. adults. JAMA. 2003;289:70–75. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.1.70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Giesbrecht N, Wettlaufer A, April N, Asbridge M, Cukier S, Mann R, et al. Strategies to Reduce Alcohol-Related Harms and Costs in Canada: A Comparison of Provincial Policies. Toronto: Centre for Addiction and Mental Health; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gruenewald PJ, Ponicki WR, Holder HD, Romelsjo A. Alcohol prices, beverage quality, and the demand for alcohol: quality substitutions and price elasticities. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2006;30:96–105. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2006.00011.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.World Health Organization. WHO Technical Manual on Tobacco Tax Administration. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Delipalla S, Keen M. The comparison between ad valorem and specific taxation under imperfect competition. J Public Health Econ. 1992;49:351–367. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhao J, Stockwell T, Martin G, Macdonald S, Vallance K, Treno A, et al. The relationship between minimum alcohol prices, outlet densities and alcohol-attributable deaths in British Columbia, 2002–09. Addiction. 2013;108:1059–1069. doi: 10.1111/add.12139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Purshouse RC, Meier PS, Brennan A, Taylor KB, Rafia R. Estimated effect of alcohol pricing policies on health and health economic outcomes in England: an epidemiological model. Lancet. 2010;375:1355–1364. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60058-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sornpaisarn B, Shield KD, Rehm J. Alcohol taxation policy in Thailand: implications for other low- to middle-income countries. Addiction. 2012;107:1372–1384. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2011.03681.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.An R, Sturm R. Does the response to alcohol taxes differ across racial/ethnic groups? Some evidence from 1984–2009 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System. J Ment Health Policy Econ. 2011;14:13–23. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]