Abstract

Every community is unique and has special strengths and health-related needs, such that a community-based participatory research partnership cannot be formed and implemented in a predetermined, step-by-step manner. In this article, we describe how the Community Partnership Model (CPM), designed to allow flexible movement back and forth through all action phases, can be adapted to a variety of communities. Originally developed for nursing practice, the CPM has evolved into approaches for the collaborative initiation and maintenance of community partnerships. The model is informed by the recognition that cultural, social, economic, and knowledge backgrounds may vary greatly between nurse researchers and their community partners. The Familias En Acción violence prevention project exemplifies the use of the CPM in a transcultural partnership formation and implementation process. The collaborative approaches of the model guide community and research partners to interconnect and move flexibly through all partnership phases, thereby facilitating sustainability and community self-advocacy.

Keywords: community nursing research partnerships, violence prevention program, community-based violence prevention

Community-based participatory research (CBPR) encourages the formation of effective working relationships between communities and researchers focused on common goals, democratic decision making, team effort, shared outcomes, and mutual benefits (Israel et al., 2005, pp. 6–9). CBPR brings communities into the research process in ways that enable them to contribute to the development, conduct, and evaluation of projects designed to improve health and reduce health disparities in their neighborhoods. Desired outcomes include building community capacity, competence, confidence, and capital (Flaskerud & Anderson, 1999).

Although CBPR has achieved recognition in the fight to reduce health disparities, minimal attention has been directed to the process of partnership development within the complex dynamics of specific communities and across widely differing communities and cultural groups. Step-by-step approaches to CBPR assume linear movement from one completed step to another. The fluid reality of community partnerships requires a cyclical process of discovery that allows for and even encourages movement in unanticipated directions and also pays great attention to the cultural beliefs and practices of all partnership participants. The purpose of this article is to describe the Community Partnership Model (CPM). Based on CBPR concepts, the CPM offers a fluid and flexible approach for initiating and maintaining community research partnerships. The collaborative approaches of the model guide community and research partners to interconnect and move flexibly through all partnership phases, thereby facilitating sustainability and community self-advocacy. The Familias En Acción violence prevention project illustrates the application of the CPM in a transcultural partnership formation and implementation process.

CBPR Philosophical Grounding

CBPR philosophical underpinnings provide guidance for partnerships within the social and cultural environment of the community (Fals Borda, 2006; Freire, 1970; Lewin, 1997; Trickett, 2011). These underpinnings have become traditions expressed in CBPR concepts of shared decision making. Anchored in applied social science and social activism, CBPR concepts are similar to critical theory in examination of sociopolitical contexts (Fontana, 2004; Madison, 2005). They help us acknowledge multiple ways of knowing through critical reflection and concepts of equality, shared power, cooperation, and mutual inquiry. They engage community members in the process of solving the problems they identify, with the goal of securing social justice (Horn, McCracken, Dino, & Brayboy, 2008; Kemmis & McTaggart, 2003; Minkler & Wallerstein, 2008).

The constantly shifting and dynamic nature of complex, interconnected communities and research entities and their ongoing interactions present enormous challenges for the process of forming and sustaining partnerships. No two communities are alike; some already have organized projects and work to improve the health and environmental status in their neighborhoods. Some communities have identified what they think needs to be done to improve the quality of community life and seek outside assistance. In some communities, factions within the community disagree about what is needed. Other communities resent researchers.

We present the CPM for collaborative transcultural community nursing research partnerships designed to allow flexible movement back and forth through action phases that can be adapted to a variety of communities. The CPM takes into account the continuously evolving variations in communities and research entities.

The Community Partnership Model

The CPM has evolved over time from a practice model (Anderson, 1978) intended to involve patients in their own care into a collaborative approach for the initiation and maintenance of community partnerships (Anderson, 2005; Anderson, Calvillo, & Fongwa, 2007). Based on CBPR philosophical grounding, the CPM model is influenced by the recognition that cultural and social ways of learning and acquiring knowledge may vary between health care researchers and research participants (Kleinman, 1978, 1980). When community partnerships are being negotiated, these variations in viewpoints, core values, and beliefs may interfere with effective working relationships. Recognition of this potential for varied perspectives can motivate strategies that avoid or mitigate miscommunications.

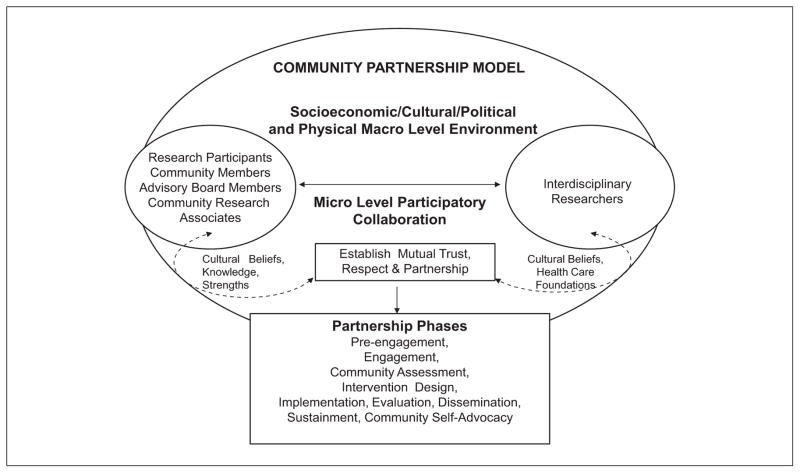

Closely connected to community members’ and researchers’ varied viewpoints are ecological and contextual considerations. Bronfenbrenner (1995) described the interconnections between a person’s culturally defined age, life course, role expectations, opportunities, and the context and timing of that life. As seen in Figure 1, dynamic interactions between partners take place within interconnected macrolevel sociocultural–political–economic environmental contexts (Anderson, 2005; Anderson et al., 2007). Working within these contexts, each partner brings personal experience, knowledge, beliefs, values, strengths, and assets to the partnership. The dynamic collaboration at the microlevel evolves over time as joint decisions and plans are made, implemented, evaluated, and disseminated. The partners work together, learn each other’s beliefs, share their particular expertise, meet challenges, resolve problems, and reap mutual rewards as they establish mutually trusting and respectful relationships. Their collaborative work is accomplished through flexible and evolving partnership process phases that allow for back-and-forth movement when partners address unexpected issues, altered intervention needs, and shifting situations within the community setting. Philosophically grounded in CBPR, the CPM uses partnership process phases that we illustrate with a case example.

Figure 1.

Community partnership model.

Partnership Process Phases

The partnership process phases include preengagement, engagement, community assessment, intervention design, implementation, evaluation, dissemination, sustainment, and community self-advocacy.. Throughout these phases, partners engage in discussions about capacities, resources, liabilities, and social justice issues as they arise during the process of collaboration. Together they create a nurturing and flexible environment for open communication, listen to each other’s viewpoints, and celebrate differences while seeking approaches to agreement by establishing a climate of openness to new ideas and ways of viewing the world. Consideration for each other among the partners provides the basis for ensuring mutual trust and respect and, as the team works back and forth through the phases, serves to identify, modify, and implement a plan of action. The intent of this process is sustained translation of project outcomes and increased community self-advocacy.

Case Example

Familias en Acción: A Youth Violence Prevention Program was guided by community partnership principles that linked academic researchers and community members in a paradigm of collaboration and shared power. In this article, the Familias en Acción program provides an example of the partnership process phases from preengagement through planning for sustainability and community advocacy. Residents of a Latino community in south Texas partnered with academic researchers to develop and conduct community-wide surveys on violence attitudes and behaviors and a series of community-wide violence awareness events. In addition, they selected a violence prevention program based on Latino cultural values (El Joven Noble) to implement and evaluate among elementary school children.

Interpersonal violence disproportionately affects youth living in Latino communities throughout the United States. In 2010, homicide was the second leading cause of mortality among youths 10 to 24 years of age; for Latino male youth, homicide occurred at more than four times the rate of that for non-Latino White male youth (CDC, 2010). Young Latino males are also twice as likely to suffer a firearm-related injury and be the victims of a violent crime in their own neighborhood than are non-Latino White males (Lauritsen, 2003; Reich, Culross, & Behrman, 2002, p. 8). Various risk factors for interpersonal violence have been documented, including community residence, poverty, victimization, availability of firearms, substance use, and limited access to physical and mental health services (Resnick, Ireland, & Borowsky, 2004).

Preengagement Phase

Preengagement as described by Campbell-Voytal (2010) initiates the engagement phase and begins the process of mutual discovery. During this phase, community members and researchers engage in shared work activities that meet a community need while building mutual trust and respect. This phase is an opportunity for community members and researchers to learn about each other: for community members to reveal their resources and expertise and researchers to demonstrate their commitment to the community and relevant health-related expertise. Shared work efforts help the partners determine the level of community interest and capacity for a partnership (Campbell-Voytal, 2010). Working together enables community and researchers to find common ground for engaging in a partnership.

Case Example

In the summer of 2005, in preparation for implementing Familias en Acción, the academic partners conducted a literature review of the current state of multi-disciplinary and community–academic research partnerships in the United States and Canada (Lesser & Oscos-Sanchez, 2007). Four different models of research partnerships were identified: an academic researcher–controlled form, a partnership-controlled form in which academic researchers partnered with a community-based organization, a partnership-controlled form in which researchers partnered directly with members of the community, and a community-controlled form. Although infrequently seen in the literature, the fourth form is a partnership that is controlled almost entirely by the community. The Familias en Accion academic partners determined to work toward achieving a community-controlled model. Thus, before ever entering the field, the academic partners made a commitment to respect the local culture and people. They invited an experienced community organizer, a long-time resident of the partnering community, to serve as their consultant. In October 2005, the first meeting of the Familias en Acción Community Collaborative Council (CCC) was held. At that meeting the academic partners and the community consultant met several members of Southside United Against a Violent Environment (SUAVE). In 1996, after suffering the loss of children in a wave of violence, residents and school district personnel joined together and formed SUAVE to collectively address the issue of increasing youth violence that was sweeping throughout the United States and their community. The academic partners quickly recognized that this community already had the collective experience and shared wisdom that would make the project successful.

An assistant school superintendent describes the preengagement process as follows:

The program, Familias en Acción, started with a couple of ladies coming to visit me, both PhD nurses. They had this great idea for an antiviolence program for children. Of course, the first thing I thought about was, “OK, how much is this going to cost us and how much time is it going to take?” … What I later realized was that it was more than just an antiviolence character education program for the kids. It turned out to be a community mobilization project. … I really thank the UT Health Science School of Nursing. I think they have done a great job in working with us. And I feel very honestly that not only have we learned from them, but we’ve done a good job teaching them some things.

Engagement Phase

This phase may merge with the preengagement and the community assessment phases and involves the process of mutual identification of interested partners within the community and the academy. An important consideration in this process is ensuring a balance between community members, key informants, community leaders and advocates, agency directors, and interdisciplinary researchers. Determining the community-relevant strategies to ensure this balance requires community direction. The choice of strategies that engage the community also depends on community preferences to decide which type of engagement format (community forums, meetings, and/or small group discussions) will encourage community members as well as leaders to participate in discussion and decision making. The engagement process can be enhanced by establishing a coleading, cote-aching, colearning format for meetings and events and transparency in decision making (Israel, Schulz, Parker, & Becker, 1998; Israel et al., 2005, pp. 6–12; Minkler & Wallerstein, 2008). Agendas, minutes, memoranda of understanding, and appropriate community accessible media connectedness as well as mutually determined ground rules make it easier to ensure equity of power and participation.

Case Example

During the first meeting with both community and school representatives, the community members quickly identified key stakeholders who should be included in the project. An environment of trust was created by establishing a community-controlled model of a community–academic research partnership. The goal was to advance self-governance by the community partners at each phase of the project. To make decisions, the Familias en Acción Community Collaborative Council (CCC) was formed. It included community members, representatives from local community-based organizations, and school district teachers, administrators, and social workers. The issue of how decisions were to be made was raised for discussion. The members chose to make decisions by consensus vote. The academic partners agreed to have a voice but no vote. They believed that this contributed to creating a positive environment of respectful trust for the shared wisdom of the community.

A community research team member describes his role in the project, from community member volunteer to research team member:

I am part of this project called Familias en Acción that we started a few years ago. I started as a volunteer. I was brought to the project by a friend, a social worker from the Alternative Center. He felt this was something that I would really believe in and actually something I could enjoy since he knew the heart I have for children in the community. It started well … we went to the meetings; I started helping out and volunteering. But afterwards, I was blessed with a great opportunity and was hired at the UT Health Science Center School of Nursing to be an actual staff member of this project … which was a tremendous blessing with all the things that came about during that time. It has been a tremendous journey, walking with many different families of this community and what it has meant to be a part of this. And the uniqueness of this was that it was all community-driven.

Community Assessment Phase

Community members participate in the assessment process (Israel et al., 2005). Community members know their neighborhood boundaries and contribute to collection of local knowledge and resources. Researchers contribute census, epidemiology, and technology resources. Assessments seek community strengths and assets as well as needs and liabilities. Specific assessment methods vary according to the particular community. Survey, photovoice, and mapping strategies enable community members to work side by side with researchers and clinicians during the assessment of assets, needs and contexts (Aronson, Wallis, O’Campo, & Schafer, 2007; Belansky, Cutforth, Chavez, Waters, & Bartlett-Horch, 2011). Individual and group interviews among residents of neighborhoods within the larger community add another dimension to assessment.

Case Example

In an effort to better understand some of the community’s contextual factors and attitudes toward violence, a cross-sectional community-based survey was conducted with 473 participants randomly selected by block. The survey included measures of social capital (collective efficacy and neighborhood block conditions). Although the academic partners developed the initial drafts of the survey, members of the CCC recruited other community members to help them review and pilot test the instruments as well as collect all the data. All community members collecting data were trained in data collection methods and in the protection of the rights of human research subjects and were formally certified, and the full project received institutional review board approval.

The survey participants’ attitudinal scores indicated little tolerance for violence. In addition, two measures of social capital (collective efficacy and neighborhood block conditions) were positively associated with and predictive of negative attitudes toward violence. The results suggested that to be successful, violence prevention programs in this community needed to strengthen the sense of collective efficacy as well as improve neighborhood conditions (Kelly, Rasu, et al., 2010).

Intervention Design Phase

The CPM provides guidance for engaging communities in the design, implementation, and evaluation of their own prevention programs. It is well suited for the inclusion of community values, cultural and religious heritage, and historical perspectives for both the research process and product. The community determines what will work based on the socio-cultural, political, and physical environment. Researchers provide several topically relevant alternative approaches and instruments for the community to evaluate. The CPM model can be conducted using qualitative, quantitative, and clinical trial methods with method selection based on what best fits the community assets and needs.

Case Example

Commitment with the funding agency included conducting a primary violence prevention research project with elementary school children, but the curriculum was to be chosen by the community. The CCC developed the process for selecting the curriculum. After reviewing various options, the CCC decided to be presented with three curricula. The CCC perceived these curricula as being particularly culturally relevant to the Latino community. The committee then requested to see the three programs in action. Through this process the CCC chose El Joven Noble (Tello, 2003). Members felt it was both the most novel program and most likely to be effective with “tougher” students. Community members were concerned with the growing influence of violent gangs in their neighborhoods.

Based on a risk and resiliency framework, Tello’s program (2003) addresses the spirit-breaking cycle of internalized oppression that is reflected in self-injurious behaviors such as indiscriminate and unprotected sexual activity, relationship violence, and substance use. The curriculum includes the examination of culture, identity development, male and female relationships, racism, oppression, substance abuse, violence, community involvement, and planning for the future as a basis for character development. Activities are informed by traditional teachings based on culturally rooted concepts and on the values believed necessary to build and maintain harmonious and balanced relationships. These are reported in the indigenous teachings and writings of the ancestors of many Latino people, including the relationship values of respeto, dignidad, confianza, y cariño (respect, dignity, trust, and love).

Although the initial plan was to have elementary school teachers implement the intervention program, the members of the CCC decided to be trained and to implement El Joven Noble themselves. In the summer of 2006, twenty community members and school district employees were trained in El Joven Noble by Jerry Tello (2003).

A parent/program facilitator speaks of his experience:

We’ve started a great program here on the Southside. It has been amazing. … I was invited to the second meeting of the project and I kind of freaked out the first time I went. Here we go again, all these white people thinking that they are going to fix us, that they know what is best for us. Then after getting to hear what they had to say, it kind of brought out things that I had always wanted to do with the kids. … We started getting together, we started meeting a lot. … Then eventually we had to decide on a program. We decided on a great program, Joven Noble, basically implemented just for kids. And we got to teach it. We went to a lot of classes … they taught us a lot about how to work with the kids, how to help them open up. … This program has been fantastic.

Implementation and Evaluation Phases

By this time the collaborative team has usually developed into a cooperative working unit with well-established work roles, lines of communication, problem-solving mechanisms, appreciation of each other’s expertise, and supportive strategies. It is also possible that a project will lose or gain new members or experience other changes requiring a return to earlier phases. In these interrelated phases, project-specific methods that have been agreed upon are implemented. Evaluation plans are incorporated into the intervention with programmed time for reflection as well as measurement (Sanchez, Carrillo, & Wallerstein, 2011).

Case Example

A prospective, randomized controlled design was used to examine the effects of participation in El Joven Noble (2003) on violence-related attitudes among third, fourth, and fifth grade students at the 14 elementary schools of the participating school district. Randomization occurred at the school level. Students from the 7 intervention schools participated in El Joven Noble in Year 1, and students from the 7 delayed-entry control group schools received the intervention in Year 2. The 10-session El Joven Noble curriculum was implemented weekly during an existing district-wide after-school program. Three hundred and twelve students participated in the program evaluation: 180 in the intervention group and 132 in the delayed-intervention control group.

At-risk students who participated in the El Joven Noble intervention had significantly greater nonviolent self-efficacy and demonstrated significantly greater endorsement of program values compared with at-risk students who were in the control group. Consistent with the fact that the El Joven Noble curriculum was originally developed for use among youth already involved in risky behavior, the program showed secondary violence prevention program effects. For more detailed information on methods, analyses, and results, see Kelly, Lesser, et al. (2010).

Dissemination, Sustainment, and Community Self-Advocacy Phases

As with all preceding phases, dissemination and plans for sustaining the partnership and positive project outcomes require collaborative equity for work, support, and rewards. Incorporated into these phases are joint authorship for all scientific and local publications, dissemination within the community by community members, discovery of continuing and new funding sources, and creative strategies for the community to continue and improve the intervention. Self-advocacy may require and/or benefit from skill development in order to lobby local and regional government for policy change (Israel et al., 2010).

Case Example

Community members actively engaged in disseminating the project activities. CCC members presented at regional, national, and international research conferences as well as at local community events, including Parent Teacher Association and other school-associated parent meetings. Publications were jointly authored by researchers and community members (Kelly, Lesser, et al., 2010; Kelly, Rasu et al., 2010).

Planning for sustainability began early in the process, so that the turnaround time from proposal submission, review, resubmission (if necessary), and actual funding did not result in a complete falling off of partnership activities. The partnership for this project has been sustained through the receipt of National Institutes of Health (NIH) funding so that the Familias en Acción CCC is in the process of completing a scientific evaluation of El Joven with a population of high-risk middle and high school students attending a disciplinary alternative school setting. A school district social worker describes her experience with the program and thoughts about sustainability:

I started with the program from the beginning. I’m an employee of the school district, a social worker. A group of us went to that initial meeting. … It was a leap of faith. We didn’t exactly know where the program was going, but we went with it. We liked the idea of empowering the community, we liked the idea of sustainability, we liked the idea that the community itself was going to be running the program. … I’ve seen people grow and develop their leadership skills. … The impact of the program was not something we all saw in the beginning … but looking back on it, it started as a leap of faith and hopefully it continues and we all continue to invest in it and continue to work as we have.

Self-advocacy is taking place through volunteerism in the community in a number of ways. For example, Las Mujeres de Harlandale, a volunteer group formed in 2007 under the umbrella of Familias En Acción, continues the monthly meetings and community advocacy work. Las Mujeres advocates for community change, a result of feeling powerless growing up in a community filled with social injustices. The group builds working relationships to empower women to find solutions to affect the community in a positive way. The group focuses on the future: to educate, train, and empower young women in the group to bring about lasting community change. Las Mujeres has become a venue through which adult women pass along their wisdom to the next generation, so that younger women can better overcome the societal hurdles that affect health and welfare (Fowler et al., in press). One Mujer explains:

I’m a grandmother of 11 grandchildren scattered through the school district. We started the Mujeres Nobles de Harlandale. We want all these women to bring all their knowledge, all their gifts to the table. … Everything is about trying to make a difference. … I am so grateful for this opportunity to make, not a big difference, but make a difference for me and hopefully for a couple of other people’s tomorrows.

Conclusion

It turned out to be a community mobilization project. Before I knew it all sorts of folks from the community: parents, community people, professional people … all coming together. And I think, aside from the piece with character education and violence prevention, we’ve gotten these same community people empowered; parents, grandparents, aunts, uncles, they all have come together and some have even become instructors themselves. To become a teacher, I think, is a tremendous power.

—Assistant Superintendent

The CPM recognizes the cultural and health beliefs of each member of the partnership and considers the context of the social, political, and built environment of the community, as the partners work together, share leadership, learn from each other, set goals, make decisions, plan, revise, and implement interventions, evaluations, dissemination, and future efforts to reduce health disparities. The case example shows how a transcultural collaboration between nurse researchers and community members worked to meet community-identified goals and to find solutions to community-identified problems. If emancipation from oppression underpins the process of collaboration, as is implicit in the perspective of critical social theory, then collaboration should help the community that is experiencing the health disparities, as well the researchers themselves, become more knowledgeable and empowered. A major aim of this type of research is to integrate knowledge with action in the form of community interventions and social change. In Familias en Acción, community participation and community membership have led to relevant and sustainable interventions.

This transcultural partnership example shows how the CPM assists community and research partners to flexibly move back and forth through the partnership phases starting with preengagement and resulting in sustainability and community self-advocacy. Community partnerships are a relationship-oriented and capacity-building process, as well as a process that allows for and encourages movement in unanticipated directions. Community partnership research, unlike traditional research, requires researchers to spend more time in the community partners’ setting, rely on the wisdom of their community partners, and learn to appropriately relinquish control in ways that enable communities to share decision-making power and mobilize their own resources.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the Familias en Acción Community Collaborative Council and Patricia J. Kelly PhD, RN, MPH. The first author acknowledges the Center for Vulnerable Populations Research, School of Nursing, UCLA National Institutes of Health /Nursing Institute for Nursing Research, NIH/NINR Project Number: P30-NR005041-08. This article was accepted under the editorship of Marty Douglas, PhD, RN, FAAN

Funding

The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: Research in case example funded in part by NIH/NINR R01-NR008565 and NIH/NICHD R01-HD057842

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- Anderson NLR. An interactive systems approach to problem solving. Nurse Practitioner. 1978;3(5):25–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson NLR. Developing theoretical approaches to inspire effective patient/provider relationships. Paper presented at the Society for Applied Anthropology; Santa Fe, NM. 2005. Apr, [Google Scholar]

- Anderson NLR. Cultural explanatory models in health and illness. Journal of Transcultural Nursing. 2010;21(Suppl 1):153S–164S. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson NLR, Calvillo ER, Fongwa MN. Community-based approaches to strengthen cultural competency in nursing education and practice. Journal of Transcultural Nursing. 2007;18(1-S):49s–59s. doi: 10.1177/1043659606295567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aronson RE, Wallis AB, O’Campo PJ, Schafer P. Neighborhood mapping and evaluation: A methodology for participatory community health initiatives. Maternal Child Health Journal. 2007;11(4):373–383. doi: 10.1007/s10995-007-0184-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belansky ES, Cutforth N, Chavez RA, Waters E, Bartlett-Horch K. An adapted version of intervention mapping (AIM) is a tool for conducting community-based participatory research. Health Promotion Practice. 2011;12(3):440–455. doi: 10.1177/1524839909334620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner U. Developmental ecology through space and time: A future perspective. In: Moen P, Elder GH, Luscher K, editors. Examining lives in context: Perspectives of the ecology of human development. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 1995. pp. 619–648. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell-Voytal K. Phases of “pre-engagement” capacity building: Discovery, exploration, and trial alliance. Progress in Community Health Partnerships. 2010;4(2):155–162. doi: 10.1353/cpr.0.0118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control. Webbased Injury Statistics Query and Reporting System (WISQARS) 2010 Retrieved from www.cdc.gov/injury.

- Fals Borda O. Participatory (action) research in social theory: Origins and challenges. In: Reason P, Bradbury H, editors. Handbook of action research. London: Sage; 2006. pp. 27–37. [Google Scholar]

- Flaskerud JH, Anderson NLR. Disseminating the results of participant focused research. Journal of Transcultural Nursing. 1999;10(4):342–351s. doi: 10.1177/104365969901000412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fontana JS. A methodology for critical science in nursing. Advances in Nursing Science. 2004;27(2):91–101. doi: 10.1097/00012272-200404000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fowler S, Venuto M, Ramirez V, Martinez E, Pollard J, Hixon J, Lesser J. The role of connection and support in community engagement: Las Mujeres y Mujercitas Nobles de Harlandale. Issues in Mental Health Nursing. doi: 10.3109/01612840.2012.719584. (in press) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freire P. Pedagogy of the oppressed. New York, NY: Seabury Press; 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Horn K, McCracken L, Dino G, Brayboy M. Applying community-based participatory research principles to the development of a smoking-cessation program for American Indian teens: “Telling Our Story. Health Education and Behavior. 2008;35(1):44–69. doi: 10.1177/1090198105285372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Israel BA, Coombe CM, Cheezum RR, Schultz AJ, McGranaghan RJ, Lichtenstein R, Burris A. Community-based participatory research: A capacity building approach for policy advocacy aimed at eliminating health disparities. American Journal of Public Health. 2010;100(11):2094–2102. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.170506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Israel BA, Eng E, Schulz AJ, Parker EA, editors. Methods in community-based participatory research for health. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Israel BA, Schulz AJ, Parker EA, Becker AB. Review of community-based research: Assessing partnership approaches to improve public health. Annual Review of Public Health. 1998;19:173–202. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.19.1.173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz DL, Murimi M, Gonzalez A, Njike V, Green LW. From controlled trial to community adoption: The multisite translational community trial. American Journal of Public Health. 2011;101(8):e17–27. doi: 10.2105/AJPH. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly PJ, Lesser J, Cheng A, Oscos-Sanchez M, Martinez E, Pineda D, Mancha J. A prospective randomized controlled trial of an interpersonal prevention program with a Mexican American community. Family & Community Health. 2010;33(3):207–215. doi: 10.1097/FCH.0b013e3181e4bc34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly PJ, Rasu R, Lesser J, Oscos-Sanchez M, Mancha J, Orriega A. Mexican-American neighborhood’s social capital and attitudes about violence. Issues in Mental Health Nursing. 2010;31:15–20. doi: 10.3109/01612840903159744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kemmis S, McTaggart R. Participatory action research. In: Denzin NK, Lincoln YS, editors. Strategies of qualitative inquiry. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2003. pp. 336–396. [Google Scholar]

- Kleinman A. Concepts and a model for the comparison of medical systems as cultural systems. Social Science and Medicine. 1978;12:85–91. doi: 10.1016/0160-7987(78)90014-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleinman A. Patients and healers in the context of culture. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Lauritsen J. How families and communities influence youth victimization. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention; 2003. NCJ201629. [Google Scholar]

- Lesser J, Oscos-Sanchez M. Community-academic research partnerships with vulnerable populations. In: Fitzpatrick J, Nayamathi A, Koniak-Griffin D, editors. Annual Review of Nursing Research. Vol. 25. New York, NY: Springer; 2007. pp. 317–337. Chapter 11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewin K. Resolving social conflicts and field theory in social science. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 1997. (Originally published 1948) [Google Scholar]

- Madison DS. Critical ethnography: Method, ethics, and performance. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Minkler M, Wallerstein N. Introduction to community-based participatory research. In: Minkler M, Wallerstein N, editors. Community-based participatory research for health: From process to outcomes. San Francisco, CA: Jossey Bass; 2008. pp. 5–12. [Google Scholar]

- Reich K, Culross P, Behrman R. Children, youth and gun violence: Analysis and recommendations. The Future of Children. 2002;12(2):5–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Resnick M, Ireland M, Borowsky I. Youth violence perpetration: What protects? What predicts? Findings from the national longitudinal study of adolescent health. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2004;35(5):424.e1–424.e10. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2004.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez V, Carrillo C, Wallerstein N. From the ground up: Building a participatory evaluation model. Progress in Community Health Partnerships. 2011;5(1):45–52. doi: 10.1353/cpr.2011.0007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tello J. Unpublished curriculum. Hacienda Heights, CA: 2003. El Joven Noble. available only to facilitators. Retrieved from http://www.JerryTello.com. [Google Scholar]

- Trickett DJ. Community-based participatory research as worldview or instrumental strategy: Is it lost in translation(al) research? American Journal of Public Health. 2011;101(8):1353–1355. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]