Abstract

Objective

To evaluate previously reported associations of copy number variants (CNVs) with schizophrenia and to identify additional associations, the authors analyzed CNVs in the Molecular Genetics of Schizophrenia study (MGS) and additional available data.

Method

After quality control, MGS data for 3,945 subjects with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder and 3,611 screened comparison subjects were available for analysis of rare CNVs (<1% frequency). CNV detection thresholds were chosen that maximized concordance in 151 duplicate assays. Pointwise and gene-wise analyses were carried out, as well as analyses of previously reported regions. Selected regions were visually inspected and confirmed with quantitative polymerase chain reaction.

Results

In analyses of MGS data combined with other available data sets, odds ratios of 7.5 or greater were observed for previously reported deletions in chromosomes 1q21.1, 15q13.3, and 22q11.21, duplications in 16p11.2, and exon-disrupting deletions in NRXN1. The most consistently supported candidate associations across data sets included a 1.6-Mb deletion in chromosome 3q29 (21 genes, TFRC to BDH1) that was previously described in a mild-moderate mental retardation syndrome, exonic duplications in the gene for vasoactive intestinal peptide receptor 2 (VIPR2), and exonic duplications in C16orf72. The case subjects had a modestly higher genome-wide number of gene-containing deletions (>100 kb and >1 Mb) but not duplications.

Conclusions

The data strongly confirm the association of schizophrenia with 1q21.1, 15q13.3, and 22q11.21 deletions, 16p11.2 duplications, and exonic NRXN1 deletions. These CNVs, as well as 3q29 deletions, are also associated with mental retardation, autism spectrum disorders, and epilepsy. Additional candidate genes and regions, including VIPR2, were identified. Study of the mechanisms underlying these associations should shed light on the pathophysiology of schizophrenia.

Copy number variants (CNVs) are deletions or duplications of DNA segments. Those as small as 10,000–100,000 base pairs (bp) can be detected by analyzing variations of fluorescent intensity from microarrays used in genome-wide association studies (GWAS). There are replicated associations of schizophrenia with rare CNVs on chromosomes 1q21.1 (1, 2), 15q13.3 (1, 2), and 16p11.2 (3), with suggestive support for exon-disrupting deletions in the gene for neurexin-1 (NRXN1) (see Table S1 in the data supplement accompanying the online version of this article) (4, 5). Cytogenetic methods were previously used in detecting the chromosome 22q11.21 deletions seen in patients with DiGeorge or velocardiofacial syndrome, of whom 20%–30% develop schizophrenia (6). These CNVs substantially increase the risk of schizophrenia. Remarkably, each of them is also associated with autism spectrum disorders, mental retardation, and epilepsy (6). An overall increase in the number of CNVs has been reported in individuals with schizophrenia versus comparison subjects (2, 7, 8), suggesting that additional pathogenic CNVs remain to be identified.

Here we report on a genome-wide study of rare autosomal CNVs in 3,945 subjects with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder and 3,611 screened comparison subjects from the Molecular Genetics of Schizophrenia study (MGS). The results support the four multigenic CNV associations already noted and establish NRXN1 as a specific gene associated with schizophrenia. Using data from MGS and other available data sets, we also report suggestive evidence for association with additional CNVs, including a 1.6-Mb deletion on chromosome 3q29 previously observed in individuals with mental retardation, autistic features, and/or microcephaly (9); exonic duplications in VIPR2, the gene for vasoactive intestinal peptide receptor 2, a receptor for peptides with hypothesized roles in autism (10) and schizophrenia (11); and exonic duplications in C16orf72, whose function is unknown.

Method

Subjects and DNA Specimens

Clinical methods were described elsewhere (12). Briefly, subjects affected by schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder (case subjects) who either were of European ancestry or were African American were recruited by 10 university-based sites in the United States and Australia under a common protocol. They received consensus diagnoses of DSM-IV schizophrenia (90%) or schizoaffective disorder (with schizophrenia criterion A for at least 6 months) based on available information from interviews, informants, and medical records. The comparison subjects were recruited through a nationally representative survey research panel (Knowledge Networks, Inc., Menlo Park, Calif.) (100% of subjects with European ancestry, 41% of African Americans) and Internet banner ads (Survey Sampling International, Shelton, Conn.) (59% of African Americans). They denied a history or treatment of psychosis or bipolar disorder in an online questionnaire. Table 1 describes the two groups.

TABLE 1.

Sources of Data for Analyses of Copy Number Variants (CNVs) in Schizophrenia

| Subjects in Molecular Genetics of Schizophrenia Study (MGS) |

Comparison Subjects (Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia)b |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group | Total | DNA From Lymphoblastic Cell Lines |

DNA From Blood |

Subjects in International Schizophrenia Consortium (ISC) Data Set With CNVs >100 kba |

Assayed With Illumina 550K Array (13) |

Assayed With Illumina 610K Arrayc |

All Subjects |

| Subjects with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder |

|||||||

| European ancestry | 2,671 | 1,998 | 673 | 3,391 | 6,062 | ||

| African American | 1,274 | 1,004 | 270 | 0 | 1,274 | ||

| Total | 3,945 | 3,002 | 943 | 3,391 | 7,336 | ||

| Comparison subjects | |||||||

| European ancestry | 2,648 | 2,623 | 25 | 3,181 | 886 | 3,532 | 10,243 |

| African American | 963 | 962 | 1 | 0 | 582 | 3,029 | 4,574 |

| Total | 3,611 | 3,585 | 26 | 3,181 | 1,464 | 6,561 | 14,817 |

| All subjects | 7,556 | 6,587 | 5319 | 6,572 | 1,464 | 6,561 | 22,153 |

Data are from the web site (http://pngu.mgh.harvard.edu/isc/isc-r1.cnv.bed) for the ISC study (2).

Data used only for analyses of the strongest MGS findings.

Data were provided by study authors (H.H. and K.W.).

Most DNA specimens were extracted from Epstein-Barr virus-transformed lymphoblastic cell lines. Some were extracted from blood (primarily for the case subjects, for whom the National Institute of Mental Health repository expected fewer access requests) (Table 1). Because Epstein-Barr virus transformation can create CNVs (14), we excluded samples and chromosomal regions with possible artifacts and tested the case subjects for CNV differences between DNA from lymphoblastic cell lines and blood. The lymphoblastic cell lines from the case and comparison groups had similar estimated doubling times (25–30) prior to cryopreservation.

GWAS Assay and Detection of CNVs

The specimens were assayed at the Broad Institute, Cambridge, Mass., by using Affymetrix 6.0 genotyping arrays (Affymetrix, Santa Clara, Calif.); the assays included approximately 900,000 single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) plus approximately 900,000 copy number probes. CNVs were detected, or “called,” with the Birdseye module of the Birdsuite software package (15), version 2 (internal version 1.3), which uses a hidden Markov model algorithm. The data were normalized within plates of up to 92 DNA samples. HG18 human genome build locations are reported.

CNV Quality Control Analyses

We relied on four quality control steps to reduce the calling errors expected to result from background variations in probe fluorescent intensities.

CNV call quality control

Separately for each copy number, we identified criteria that maximized concordance between duplicate assays for 151 specimens (although some errors are concordant). We merged nearby pairs (or sequential pairs) of deleted or duplicated segments flanking a “normal” segment containing less than 20% of the probes in the merged CNV (primarily in segmental duplication regions); alternative merger procedures did not achieve better concordance. Table S2 in the online data supplement lists narrow and broad call criteria, which produced concordance rates of 93% and 83%–84%, respectively, for deletions and 78% and 72% for duplications; calls for larger duplications (50 or more probes) were more concordant (82%). We also excluded CNV calls (Table S3 in online data supplement) that overlapped (50%) with telomeres (100,000 bp) and centromeres, where CNV calls may be unreliable, or immunoglobulin gene regions where Epstein-Barr virus transformation causes structural changes (14). We also excluded CNVs seen predominantly on one or two plates, suggesting artifact. See Table S4 in the online data supplement for further details.

Quality control of DNA samples

We excluded 1) samples with total numbers of narrowly defined deletions or duplications exceeding the group mean by 3 standard deviations, 2) those with more than two chromosomes with outlier call numbers, 3) data for outlier chromosomes for subjects with one or two such chromosomes, and 4) samples (mostly lymphoblastic cell lines) with probe intensity variances exceeding the group mean by 4 standard deviations (predicting fewer CNV calls).

Visual confirmation

For 633 CNV calls in 36 regions of interest (to be described in the following), visual inspection of plots of (log of the mean intensity of probes for each location divided by the plate mean) supported 97.9% of the calls (including all of the calls reported here for new and confirmed CNV findings), and a second calling algorithm (16) confirmed 92.6% on the basis of point-by-point copy number estimates. Although agreement of two or more algorithms has been required for CNV calls by some studies (8, 17), we were unable to improve duplicate concordance with a second algorithm (14) and relied instead on the algorithm developed specifically for this platform (15).

Quantitative polymerase chain reaction

Selected CNVs were confirmed with quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) (Table S5, online data supplement).

Analysis of CNV Association

Narrowly and broadly defined deletion and duplication data sets were created for each ethnic group and for all subjects. Using PLINK software (18), we scanned the genome with pointwise analyses for each file, for all rare CNVs (with <1% frequency) and those of more than 100,000 bp, and for DNA samples of case subjects derived from lymphoblastic cell lines versus blood. PLINK defines points as the start and end of all CNVs plus 1 bp beyond each endpoint, counts the number of CNVs at each point, and excludes CNVs with a specified length overlap (here, 50%) with points having CNVs in a specified proportion of subjects (here, 1%). One-sided pointwise nominal and genome-wide empirical p values were computed from 50,000 permutations of case-control status. Regions containing points with empirical genome-wide p values less than 1 (suggestive association) were examined to discern effects of the call criteria or DNA source and to identify the segments contributing to the signal. Then, counts of CNVs disrupting at least one exon were determined for each RefSeq gene (according to HG18 locations). Suggestive associations were observed only for genes with total frequencies less than 0.5%. On the basis of pointwise and exonic results, regions and genes were identified for visual and experimental validation and for analysis using additional data sets.

After excluding the five regions already shown to be associated with schizophrenia and CNVs greater than 4,000,000 bp (which showed a large excess of lymphoblastic cell line specimens but no case-control difference), we performed case-control analyses of the number of CNVs per subject genome-wide (using PLINK) for deletions or duplications in five size ranges and for gene-disrupting, exon-disrupting, and “singleton” (unique in the data set) CNVs; we also analyzed the numbers of CNVs in DNA samples from lymphoblastic cells versus blood (in case subjects).

Additional CNV Data

For 1q21.1 and 15q13.3, we incorporated published data from the International Schizophrenia Consortium (ISC) (2) and the SGENE collaboration (1), which included deCODE Genetics (Reykjavik, Iceland); the Scottish data were omitted from the SGENE report because they were also used by ISC. For 16p11.2 duplications, we included ISC and a published meta-analysis (without the data set from the Genetic Association Information Network, which is from MGS) (3). We added MGS and ISC data to a meta-analysis of exonic NRXN1 deletions (deleting the Bulgarian data, which overlap with those in ISC) (4). These large CNVs should be well assayed by the diverse platforms.

For candidate regions, we used publicly available ISC data for rare CNVs larger than 100 kb (http://pngu.mgh.harvard.edu/isc/isc-r1.cnv.bed) (Affymetrix 500K assay, 5.0 or 6.0 arrays) and two childhood comparison data sets from Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia primary care clinics: 1,464 unrelated children ages 0–18 with no recorded serious medical or neurodevelopmental diagnoses (assessed with Illumina 550K arrays [Illumina, San Diego] and the DNAcopy 1.7 module of the R statistical package) (13) and 6,561 unscreened children (mean age=12.75 years, SD=4.2) (assessed with Illumina 610K arrays and PennCNV software [14]; data provided by H.H. and K.W.). Illumina calls containing three or more probes were counted. Because the numbers of probes differed in each region, the analyses with the Philadelphia comparison subjects were exploratory, but virtually identical CNVs were detected by each platform in these regions, with similar frequencies in the Philadelphia and MGS comparison subjects. The use of childhood comparison subjects is justified because unscreened comparison subjects do not reduce the power for rare diseases (i.e., those with less than 1% frequency). Any excess of undetected neuropsychiatric disorders (expected to be small in these primary care patients) would make these analyses conservative.

Statistical Analyses and Thresholds of Significance

For candidate CNVs (defined by narrow call criteria), two types of association tests were performed: Fisher’s exact case-control tests on the pooled groups and the (one-sided) stratified Cochran- Mantel-Haenszel exact test (19) (http://sekhon.berkeley.edu/stats/html/mantelhaen.test.html). These tests differ when one or more strata have imbalances in the case-control ratio, which is the case for some of the additional data sets included in our analyses. For Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel tests, we separated the MGS European-ancestry and African American groups and other data sets.

In the online data supplement (Supplementary Methods, p. S18) we discuss the problem of selecting exact test thresholds for genome-wide significant association (corrected p<0.05) and suggestive association (expected less than once per genomewide study). As guidelines for interpreting results, we suggest thresholds of p<10−5 for significant and p<0.0005 for suggestive association.

Clinical Data

We examined clinical data for case subjects with selected CNVs versus all other case subjects.

Results

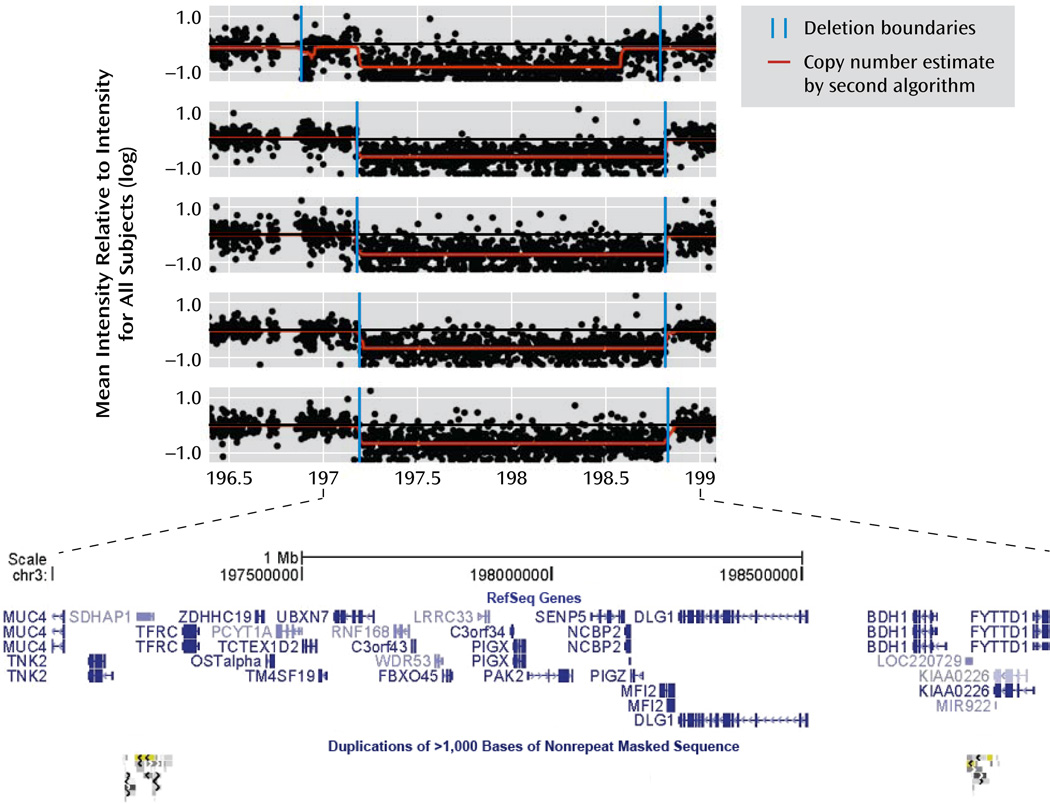

Table 2 shows results for the candidate CNVs that showed the strongest evidence for association in all of the available data. Suggestive association (p<0.0005) was observed, after addition of the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia comparison subjects, for C16orf72 exonic duplications and 1.6-Mb 3q29 deletions. VIPR2 duplications showed consistency across all available data sets. Figure 1 shows plots of large 3q29 deletions in five MGS case subjects.

TABLE 2.

| Most Significant New Association Results for Copy Number Variants (CNVs) in Schizophrenia | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group or Analysis | VIPR2: Chromosome 7, 158.51–158.63 Mb, Exonic Duplications |

AGTPBP1: Chromosome 9, 87.35–87.55 Mb, Exonic Duplications |

GLB1L3/2: Chromosome 11, 133.65–133.69 Mb, Exonic Deletions |

|||

| With | Without | With | Without | With | Without | |

| Molecular Genetics of Schizophrenia study (MGS) (current study) |

||||||

| European-ancestry case subjects | 7 | 2,664 | 4 | 2,667 | 6 | 2,665 |

| European-ancestry comparison subjects | 1 | 2,647 | 0 | 2,648 | 2 | 2,646 |

| African American case subjects | 3 | 1,271 | 1 | 1,273 | 9 | 1,265 |

| African American comparison subjects | 1 | 962 | 0 | 963 | 1 | 962 |

| Total case subjects | 10 | 3,935 | 5 | 3,940 | 15 | 3,930 |

| Total comparison subjects | 2 | 3,609 | 0 | 3,611 | 3 | 3,608 |

| p | Odds Ratio (CI) | p | Odds Ratio (CI) | p | Odds Ratio (CI) | |

| Meta-analysis, Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel exact testa | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.009 | |||

| One-sided odds ratio (CI, lower bound)b | 4.6 (1.2) | (1.1) | 4.3 (1.4) | |||

| Two-sided odds ratio (CI) | 4.6 (1.0–42.9) | (0.9) | 4.3 (1.2–23.2) | |||

| Pooled analysis, Fisher’s exact testa | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.007 | |||

| One-sided odds ratio (CI, lower bound)b | 4.6 (1.2) | (1.1) | 4.6 (1.5) | |||

| Two-sided odds ratio (CI) | 4.6 (1.0) | (0.8) | 4.6 (1.3–24.8) | |||

| With | Without | With | Without | With | Without | |

| International Schizophrenia Consortium study (ISC)c | ||||||

| Case subjects | 4 | 3,387 | — | — | — | — |

| Comparison subjects | 0 | 3,181 | — | — | — | — |

| p | Odds Ratio (CI) | |||||

| Meta-analysis of MGS and ISC studies, Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel exact testd |

0.004 | |||||

| One-sided odds ratio (CI, lower bound)b | 6.4 (1.8) | |||||

| Two-sided odds ratio (CI) | 6.4 (1.5–58.3) | |||||

| With | Without | With | Without | With | Without | |

| Comparison subjects (Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia)e |

||||||

| European ancestry | 3 | 4,415 | 5 | 4,413 | 6 | 4,412 |

| African Americans | 2 | 3,609 | 1 | 3,610 | 6 | 3,605 |

| Total subjects from all studies | ||||||

| Case subjects | 14 | 7,322 | 5 | 3,940 | 15 | 3,930 |

| Comparison subjects | 7 | 14,814 | 6 | 11,634 | 15 | 11,625 |

| Proportion of case subjects | 0.0019 | — | 0.0013 | — | 0.0038 | — |

| Proportion of comparison subjects | 0.0005 | — | 0.0005 | — | 0.0013 | — |

| p | Odds Ratio (CI) | p | Odds Ratio (CI) | p | Odds Ratio (CI) | |

| Pooled analysis (Fisher’s exact test) | 0.002 | 0.12 | 0.003 | |||

| One-sided odds ratio (CI, lower bound)b | 4.0 (1.8) | 2.5 (0.7) | 3.0 (1.5) | |||

| Two-sided odds ratio (CI) | 4.0 (1.5–11.9) | 2.5 (0.6–9.7) | 3.0 (1.3–6.5) | |||

| Range | Range | Range | ||||

| Size (kb) | 76–648 | 88–117 | 20–91 | |||

| Number | Number | Number | ||||

| MGS subjects with CNV >100 kb | 11/12 | 2/5 | 0/18 | |||

| Probes in region, Affymetrix 6.0/ Illumina 610K/Illumina 550Kf |

92/32/19 | 94/28/20 | 26/15/15 | |||

| C16orf72: Chromosome 16, 9.09–9.12 Mb, Exonic Duplications |

NEDD4L: Chromosome 18, 53.86–54.22 Mb, Exonic Duplication5 |

3q29 Multigenic CNV: Chromosome 3, 197.2– 198.83 Mb, Deletions |

3q26.1 Intergenic CNV: Chromosome 3, 165.61– 165.66 Mb, Deletions |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| With | Without | With | Without | With | Without | With | Without |

| 8 | 2,663 | 0 | 2,671 | 4 | 2,667 | 2 | 2,669 |

| 0 | 2,648 | 0 | 2,648 | 0 | 2,648 | 0 | 2,648 |

| 2 | 1,272 | 6 | 1,268 | 1 | 1,273 | 3 | 1,271 |

| 0 | 963 | 1 | 962 | 0 | 963 | 0 | 963 |

| 10 | 3,935 | 6 | 3,939 | 5 | 3,940 | 5 | 3,940 |

| 0 | 3,611 | 1 | 3,610 | 0 | 3,611 | 0 | 3,611 |

| p | Odds Ratio (CI) | p | Odds Ratio (CI) | p | Odds Ratio (CI) | p | Odds Ratio (CI) |

| 0.002 | 0.12 | 0.04 | 0.05 | ||||

| (2.7) | 4.5 (0.7) | (1.1) | (1.0) | ||||

| (2.1) | 4.5 (0.6–209.5) | (0.9) | (0.8) | ||||

| 0.002 | 0.08 | 0.04 | 0.04 | ||||

| (2.6) | 5.5 (0.8) | (1.1) | (1.1) | ||||

| (2.1) | 5.5 (0.7–252.7) | (0.9) | (0.9) | ||||

| With | Without | With | Without | With | Without | With | Without |

| — | — | — | — | 2 | 3,389 | — | — |

| — | — | — | — | 0 | 3,181 | — | — |

| p | Odds Ratio (CI) | ||||||

| 0.01 | |||||||

| (1.8) | |||||||

| (1.4) | |||||||

| With | Without | With | Without | With | Without | With | Without |

| 1 | 3,531 | 0 | 4,418 | 0 | 4,418 | 1 | 4,417 |

| 1 | 3,028 | 4 | 3,607 | 0 | 3,611 | 3 | 3,608 |

| 10 | 3,935 | 6 | 3,939 | 7 | 7,329 | 5 | 3,940 |

| 2 | 10,170 | 5 | 11,635 | 0 | 14,821 | 4 | 11,636 |

| 0.0025 | — | 0.0015 | — | 0.0010 | — | 0.0013 | — |

| 0.0002 | — | 0.0004 | — | — | 0.0003 | — | |

| p | Odds Ratio (CI) | p | Odds Ratio (CI) | p | Odds Ratio (CI) | p | Odds Ratio (CI) |

| 0.0001 | 0.04 | 0.0004 | 0.05 | ||||

| 12.9 (3.3) | 3.5 (1.1) | (3.8) | 3.7 (1.0) | ||||

| 12.9 (2.8–121.4) | 3.5 (0.9–14.7) | (2.9) | 3.7 (0.8–18.6) | ||||

| Range | Range | Range | Range | ||||

| 22–900 | 82–93 | 1.6 | 6–66 | ||||

| Number | Number | Number | Number | ||||

| 5/10 | 0/7 | 5/5 | 0/5 | ||||

| 55/14/—e | 292/131/124 | 855/296/261 | 28/5/6 | ||||

Results were similar for meta-analyses of the MGS European-ancestry and African American groups conducted with the Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel exact test and with a Fisher’s exact test of the entire MGS group (pooled).

One-sided odds ratios (which have only lower bounds) are shown because of the preexisting hypotheses.

Data are from the web site (http://pngu.mgh.harvard.edu/isc/isc-r1.cnv.bed) for the ISC study (2).

Results are shown for the MGS European-ancestry, MGS African American, and ISC data sets for two regions where all or almost all of the MGS CNVs were larger than 100 kb (for which ISC data were available). Pooled results were almost identical.

Data obtained with Illumina 550K arrays are from reference 13, and those obtained with Illumina 610K arrays were provided by study authors (H.H. and K.W.).

MGS and ISC studies used Affymetrix genotyping arrays, and the comparison subjects (Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia) were assessed with Illumina arrays. There were fewer probes in each region on the Illumina arrays, but the CNVs in the Philadelphia subjects (requiring three or more probes for a call) were similar in location, size, and frequency to the MGS CNVs, except that the Philadelphia 550K group was omitted for C16orf72 because there were only three probes in the region.

FIGURE 1.

Intensity Plots of Large 3q29 Microdeletions in Five Subjects With Schizophrenia or Schizoaffective Disordera

a Deletions of approximately 1.6 Mb were observed in five case subjects from the Molecular Genetics of Schizophrenia study (MGS), two in the International Schizophrenia Consortium study (ISC), and none of the comparison subjects in MGS, ISC, or the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia group (plotted with genomic coordinates from the Human Genome 18 reference sequence). Each subject’s mean intensity for probes at each location was divided by the mean intensity for all subjects on the DNA plate; each point in the plot is the log of this result. Values of −1, 0, and 1 represent copy numbers of 0, 2, and 4, respectively; the deletions shown here have a copy number of 1. Copy number variants (CNVs) were called with the Birdseye module of the Birdsuite software package (15), version 2 (internal version 1.3). Copy numbers were also estimated for each point by a second algorithm (16). The browser plot at the bottom of the figure (from the University of California, Santa Cruz, Genome Browser, http://genome.ucsc.edu) shows the genes in the region and the segmental duplications that surround (and probably generate) the typical 21-gene deletion, including TFRC to BDH1 (see Table S7 in the online data supplement). The first plot illustrates the ambiguities of microarray intensity data, with the two algorithms interpreting the variability of intensity somewhat differently at each boundary. Several small CNVs in the region, including some in comparison subjects, are not shown.

Table 3 shows results for five previously reported CNV regions. Combined analyses produced high odds ratios and p values that were genome-wide significant (p<10−5) by either test for long deletions of chromosomes 1q21.1, 15q13.3, and 22q11.21, duplications in 16p11.2, and deletions of NRXN1 exons. Weaker association evidence was observed for duplications in 1q21.1. No association (p>0.05) was observed in the combined MGS and ISC group for 15q13.3 duplications (seven case subjects, two comparison subjects) or NRXN1 exonic duplications (two case subjects and no comparison subjects).

TABLE 3.

| Results in New Study Groups for Previously Reported Copy Number Variants (CNVs) in Schizophreniaa | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Groupb,c or Analysis | 1q21.1 Deletions, 144.6–46.3 Mb |

1q21.1 Duplications, 144.6–46.3 Mb |

15q13.3 Deletions, 28.7–30.3 Mb |

|||

| With | Without | With | Without | With | Without | |

| MGS total case subjects (current study) | 4 | 3,941 | 7 | 3,938 | 7 | 3,938 |

| MGS total comparison subjects (current study) | 1 | 3,610 | 0 | 3,611 | 1 | 3,610 |

| MGS European-ancestry case subjects | 2 | 2,669 | 5 | 2,666 | 7 | 2,664 |

| MGS European-ancestry comparison subjects | 1 | 2,647 | 0 | 2,648 | 1 | 2,647 |

| MGS African American case subjects | 2 | 1,272 | 2 | 1,272 | 0 | 1,274 |

| MGS African American comparison subjects | 0 | 963 | 0 | 963 | 0 | 963 |

| ISC case subjects | 9 | 3,382 | 3 | 3,388 | 8 | 3,383 |

| ISC comparison subjects | 1 | 3,180 | 1 | 3,180 | 0 | 3,181 |

| deCODE (1) Iceland case subjects | 1 | 645 | 1 | 647 | 1 | 645 |

| deCODE (1) Iceland comparison subjects | 8 | 32,434 | 12 | 32,430 | 7 | 32,435 |

| deCODE (1) Denmark case subjects | 3 | 439 | — | — | — | — |

| deCODE (1) Denmark comparison subjects | 0 | 1,437 | — | — | — | — |

| deCODE (1) the Netherlands case subjects | 0 | 806 | — | — | 3 | 803 |

| deCODE (1) the Netherlands comparison subjects (1) | 0 | 4,039 | — | — | 1 | 4,038 |

| deCODE (1) other case subjects | 3 | 2,159 | 0 | 579 | 2 | 2,097 |

| deCODE (1) other comparison subjects | 0 | 2,611 | 1 | 574 | 0 | 2,649 |

| Weiss et al. (20) case subjects | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Weiss et al. (20) comparison subjects | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| McCarthy et al. (3)d case subjects | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| McCarthy et al. (3)d comparison subjects | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Walsh et al. (8) case subjects | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Walsh et al. (8) comparison subjects | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Need et al. (21) case subjects | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Need et al. (21) comparison subjects | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Kirov et al. (4) case subjects | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Kirov et al. (4) comparison subjects | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Ikeda et al. (22) case subjects | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Ikeda et al. (22) comparison subjects | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Rujescu et al. (5) case subjects | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Rujescu et al. (5) comparison subjects | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Total case subjects | 20 | 11,372 | 11 | 8,552 | 21 | 10,866 |

| Total comparison subjects | 10 | 47,311 | 14 | 39,795 | 9 | 45,913 |

| Proportion of case subjects | 0.0018 | — | 0.0013 | — | 0.0019 | — |

| Proportion of comparison subjects | 0.0002 | — | 0.0004 | — | 0.0002 | — |

| p | Odds Ratio (CI) | p | Odds Ratio (CI) | p | Odds Ratio (CI) | |

| Meta-analysis, Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel exact test | 8.5×10–6 | 0.02 | 6.9×10–7 | |||

| One-sided odds ratio (CI, lower bound)e | 9.5 (3.5) | 4.5 (1.4) | 12.1 (4.4) | |||

| Two-sided odds ratio (CI) | 9.5 (3.0–33.4) | 4.5 (1.2–17.5) | 12.1 (3.8–42.0) | |||

| Pooled analysis, Fisher’s exact test | 2.2×10–8 | 0.002 | 2.0×10–9 | |||

| One-sided odds ratio (CI, lower bound)e | 8.3 (4.2) | 3.7 (1.7) | 9.9 (4.9) | |||

| Two-sided odds ratio (CI) | 8.3 (3.7–19.9) | 3.7 (1.5–8.7) | 9.9 (4.3–24.4) | |||

| 22q11.21 Deletions, 17.1–20.2 Mb |

16p11.2 Duplications, 29.5–30.1 Mb |

16p11.2 Deletions, 29.5–30.1 Mb |

NRXN1 Exonic Deletions, Chromosome 2, 50. 0–51.1 Mb |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| With | Without | With | Without | With | Without | With | Without | ||

| 21 | 3,924 | 13 | 3,932 | 1 | 3,944 | 10 | 3,935 | ||

| 0 | 3,611 | 1 | 3,610 | 3 | 3,608 | 1 | 3,610 | ||

| 18 | 2,653 | 10 | 2,661 | 1 | 2,670 | 9 | 2,662 | ||

| 0 | 2,648 | 0 | 2,648 | 3 | 2,645 | 1 | 2,647 | ||

| 3 | 1,271 | 3 | 1,271 | 0 | 1,274 | 1 | 1,273 | ||

| 0 | 963 | 1 | 962 | 0 | 963 | 0 | 963 | ||

| 11 | 3,380 | 6 | 3,385 | 1 | 3,390 | 3 | 3,388 | ||

| 0 | 3,181 | 1 | 3,180 | 3 | 3,178 | 1 | 3,180 | ||

| 1 | 645 | — | — | — | — | — | — | ||

| 0 | 32,442 | — | — | — | — | — | — | ||

| — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | ||

| — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | ||

| 1 | 805 | — | — | — | — | — | — | ||

| 0 | 4,039 | — | — | — | — | — | — | ||

| 1 | 1,723 | — | — | — | — | — | — | ||

| 0 | 2,148 | — | — | — | — | — | — | ||

| — | — | 0 | 648 | 1 | 647 | — | — | ||

| — | — | 5 | 18,829 | 2 | 18,832 | — | — | ||

| — | — | 12 | 1,894 | 1 | 1,905 | — | — | ||

| — | — | 1 | 3,970 | 3 | 3,968 | — | — | ||

| — | — | — | — | — | — | 1 | 232 | ||

| — | — | — | — | — | — | 0 | 268 | ||

| — | — | — | — | — | — | 3 | 1,070 | ||

| — | — | — | — | — | — | 0 | 1,148 | ||

| — | — | — | — | — | — | 1 | 470 | ||

| — | — | — | — | — | — | 3 | 2,789 | ||

| — | — | — | — | — | — | 0 | 560 | ||

| — | — | — | — | — | — | 0 | 547 | ||

| — | — | — | — | — | — | 5 | 2,972 | ||

| — | — | — | — | — | — | 5 | 33,741 | ||

| 35 | 11,365 | 31 | 9,859 | 4 | 9,886 | 23 | 12,627 | ||

| 0 | 45,361 | 8 | 29,589 | 11 | 29,586 | 10 | 45,284 | ||

| 0.0031 | — | 0.0031 | — | 0.0004 | — | 0.0018 | — | ||

| 0.0000 | — | 0.0003 | — | 0.0004 | — | 0.0002 | — | ||

| p | Odds Ratio (CI) | p | Odds Ratio (CI) | p | Odds Ratio (CI) | p | Odds Ratio (CI) | ||

| 7.3×10–13 | 2.6×10–8 | 0.88 | 1.3×10–6 | ||||||

| (20.3) | 9.5 (4.1) | 0.6 (0.2) | 7.5 (3.4) | ||||||

| (15.6–∞) | 9.5 (3.6–28.4) | 0.6 (0.1–2.2) | 7.5 (3.0–19.8) | ||||||

| <1.0×10–16 | 1.5×10–12 | 0.54 | 5.5×10–9 | ||||||

| (44.7) | 11.6 (5.8) | 1.09 (0.32) | 8.2 (4.2) | ||||||

| (35.9–∞) | 11.6 (5.6–29.3) | 1.09 (0.3–3.7) | 8.2 (3.8–19.4) | ||||||

Previously reported as associated with schizophrenia with high odds ratios. Intensity plots for the subjects in the Molecular Genetics of Schizophrenia study (MGS) are shown in Figure S1 in the online data supplement.

MGS, Molecular Genetics of Schizophrenia (current study). ISC, International Schizophrenia Consortium; data are from the web site (http://pngu.mgh.harvard.edu/isc/isc-r1.cnv.bed) for the ISC study (2).

Meta-analyses with Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel exact tests give different results when there is a substantial imbalance in the numbers of subjects in the case and control groups. Thus, separate groupings were formed for groups with such imbalances, i.e., the deCODE Icelandic, Danish, and Netherlands groups (with all other subgroups combined) and the subgroups reported for NRXN1.

Excluding the data from the Genetic Association Information Network (GAIN), which were a subset of those in MGS.

One-sided odds ratios (which have only lower bounds) are shown because of the preexisting hypotheses.

Results with pointwise empirical suggestive significance are shown in Table S6 in the online data supplement. Table S7 provides information about genes within the multigenic CNVs of interest (Tables 2 and 3). Table S8 shows additional suggestive MGS results for exonic CNVs.

In MGS analyses of genome-wide CNV number (Table S9), the case subjects showed no excess of duplications, but for large CNVs (>100 kb) they had more exonic deletions per subject than the comparison subjects (0.304 versus 0.282, empirical p<0.05) and increases in several other variables related to CNVs spanning genes (e.g., 0.628 versus 0.531 genes per CNV, p<0.05). They also had more genic and exonic deletions larger than 1 Mb and more large singleton exonic deletions per subject (0.075 versus 0.063, p<0.05). Effects were in the same direction in European-ancestry and African American subjects (Table S9c). The case subjects with DNA samples from lymphoblastic cell lines and those with samples from blood did not differ in large deletions (Table S4b), but specimens from lymphoblastic cell lines had a small excess (4.5%) of deletions smaller than 100 kb.

Confirmation was provided by qPCR for all CNVs reported in Table 3, an atypical 22q11.21 distal deletion referred to in the Discussion section, and CNVs in 3q29, VIPR2, and selected additional regions (Table S5).

Table 4 summarizes clinical data for case subjects with seven large CNVs. Uncorrected p values are shown to illustrate differences, but none was significant after Bonferroni correction. Most differences were for learning problems and seizures (see Discussion). The analyses were based on self-reported medical information because it was available for all subjects and was generally consistent with the additional data available for some patients.

Table 4.

| Clinical Features of Subjects With Schizophrenia or Schizoaffective Disorder Who Were Tested for Copy Number Variants (CNVs)a | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Strongest New Findings From Current Study |

||||||

| Clinical Feature | No CNV | 3q29 | VIPR2 | |||

| N | Proportion | N | Proportion | N | Proportion | |

| Group size | 3,766 | 5 | 10 | |||

| Male | — | 0.68 | — | 0.40 | — | 0.90 |

| African American | — | 0.32 | — | 0.20 | — | 0.30 |

| Schizoaffective disorderb | — | 0.10 | — | 0.00 | — | 0.20 |

| DSM-IV criteria metb | ||||||

| Delusions | — | 0.99 | — | 1.00 | — | 1.00 |

| Bizarre (impossible) delusions | — | 0.63 | — | 0.60 | — | 0.80 |

| Hallucinations | — | 0.95 | — | 1.00 | — | 0.90 |

| Commentary or conversing hallucinations | — | 0.50 | — | 0.40 | — | 0.50 |

| Formal thought disorder | — | 0.67 | — | 0.60 | — | 0.70 |

| Disorganized behavior | — | 0.67 | — | 1.00 | — | 0.70 |

| Negative symptoms | — | 0.83 | — | 0.80 | — | 1.00 |

| Self-reported comorbid medical conditionsc | ||||||

| Thyroid disorder | 355 | 0.10 | 2 | 0.40** | 1 | 0.11 |

| Learning problem | 760 | 0.22 | 2 | 0.50 | 3 | 0.38 |

| Seizures | 469 | 0.13 | 2 | 0.40 | 0 | 0.00 |

| Number with clinical factor scores | 3,406 | 5 | 8 | |||

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | |

| Clinical factor scoresd | ||||||

| Positive symptoms | 0.00 | 0.67 | 0.21 | — | 0.50 | — |

| Negative and disorganized symptoms | 0.01 | 0.47 | 0.06 | — | 0.22 | — |

| Mood (depressive and manic) symptoms | 0.14 | 0.74 | 0.15 | — | 0.10 | — |

| Age at onset (years) | 21.26 | 6.93 | 19.60** | 0.89 | 19.50 | 4.45 |

| Mood comorbiditye | ||||||

| Total months of illness (lifetime) | 260 | 137 | 353 | — | 293 | — |

| Months with mood syndrome (lifetime) | 18 | 48 | 2† | — | 17 | — |

| Proportion of illness with mood syndrome | 0.08 | 0.18 | 0.01† | — | 0.12 | — |

| Confirmed Association With Schizophrenia | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1q21.1 | NRXN1 | 15q13.3 | 16p11.2 | 22q11.21 | |||||

| N | Proportion | N | Proportion | N | Proportion | N | Proportion | N | Proportion |

| 4 | 10 | 7 | 13 | 21 | |||||

| — | 0.75 | — | 0.70 | — | 0.71 | — | 0.54 | — | 0.52 |

| — | 0.50 | — | 0.10 | — | 0.00 | — | 0.23 | — | 0.14 |

| — | 0.25 | — | 0.20 | — | 0.14 | — | 0.23 | — | 0.05 |

| — | 1.00 | — | 1.00 | — | 1.00 | — | 1.00 | — | 1.00 |

| — | 0.75 | — | 0.60 | — | 0.67 | — | 0.46 | — | 0.52 |

| — | 0.75 | — | 1.00 | — | 1.00 | — | 1.00 | — | 1.00 |

| — | 0.00* | — | 0.40 | — | 0.86 | — | 0.46 | — | 0.52 |

| — | 0.75 | — | 0.80 | — | 0.43 | — | 0.85 | — | 0.52 |

| — | 0.25 | — | 0.70 | — | 0.57 | — | 0.46 | — | 0.62 |

| — | 1.00 | — | 0.60* | — | 0.86 | — | 0.77 | — | 0.81 |

| 1 | 0.25 | 1 | 0.10 | 0 | 0.00 | 1 | 0.08 | 5 | 0.25** |

| 1 | 0.25 | 5 | 0.50** | 3 | 0.43 | 6 | 0.46** | 11 | 0.52*** |

| 1 | 0.25 | 4 | 0.40** | 3 | 0.43** | 5 | 0.38** | 6 | 0.29** |

| 3 | 10 | 7 | 13 | 20 | |||||

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD |

| −0.30 | — | 0.04 | — | −0.09 | — | 0.57† | — | −0.08 | — |

| 0.02 | — | 0.00 | — | −0.22 | — | 0.11 | — | −0.03 | — |

| −0.30 | — | 0.79** | — | 0.06 | — | 0.10 | — | 0.11 | — |

| 19.75 | 10.66 | 20.40 | 5.39 | 22.00 | 8.83 | 20.62 | 7.33 | 22.10 | 4.40 |

| 192 | — | 285 | — | 309 | — | 287 | 262 | — | |

| 4** | — | 10* | — | 31 | — | 37 | 24 | — | |

| 0.13 | — | 0.09 | — | 0.10 | — | 0.12 | 0.08 | — | |

Statistical tests compared subjects having the specified CNV with those having no CNVs in any of these regions (i.e., excluding from analysis those with other CNVs in each region that were not part of the main effect tested in this study, e.g., those with 1q21.1 duplications rather than deletions or those with nonexonic NRXN1 deletions rather than exonic deletions). The p values are uncorrected. Fisher’s exact tests were used for counts (one-sided for self-reported comorbid medical conditions, two-sided otherwise) and t tests for continuous variables (two-sided). The number of subjects is the number with complete data for the specified variable; some lacked valid data for some variables.

DSM-IV criteria and mood comorbidity items were rated by consensus of two diagnosticians.

Designations were made by interviewers on the basis of self-report.

Factor scores were adjusted for age, sex, ancestry, and study site and were computed with Mplus from Lifetime Dimensions of Psychosis Scale ratings (23) by a diagnostician using all available information.

Estimated by a diagnostician considering all available information.

p<0.10.

p<0.05.

p<0.01.

p<0.001.

Previously reported 500-kb deletions on chromosome 15q11.2 (1) were observed in 19 MGS case subjects and 17 comparison subjects. Exonic APBA2 duplications (21, 24) were observed in four case subjects (one duplication was 1.5 Mb) and one comparison subject. In the combined group of MGS subjects, ISC subjects, and Philadelphia subjects assessed with Illumina 550K arrays, we observed an odds ratio of 2.81 (n.s.) for exonic deletions in CNTNAP2 (seven case subjects and three comparison subjects).

Discussion

These results convincingly support the findings of substantial increases in schizophrenia risk in individuals carrying large deletions on chromosomes 1q21.1, 15q13.3, and 22q11.21, exonic NRXN1 deletions, and 16p11.2 duplications. In this section we will discuss these regions, as well as new candidate CNVs, including 1.6-Mb deletions in chromosome 3q29 and exonic duplications of VIPR2, the hypothesis of a global increase in rare CNVs, and implications for future research.

Chromosome 1q21.1

While combined analysis showed a strong association of schizophrenia with deletions in this region, the frequency of duplications in case subjects was also higher than in comparison subjects in MGS (p=0.02 in all data by meta-analysis). The patients with deletions here did not report a higher number of seizures or learning problems. The typical 1.67-Mb deletion contained 11 genes (FAM108A3 to NBPF11, Table S7) listed (annotated) in the RefSeq database. It is not known which gene or genes underlie the pathogenic effects. One proposed candidate is HYDIN (144.9 Mb), an evolutionary duplication of HYDIN on 16q22.2. It is not annotated on 1q because segmental duplications prevent it from being sequenced confidently. (Note that 1q21.1 CNVs produce false positives on 16q22.2.) The 1q21.1 isoform is expressed in the brain. Microcephaly is observed in mice with homozygous HYDIN deletions and in neurodevelopmentally impaired children and their parents with long 1q21.1 deletions (and macrocephaly with duplications) (25).

Chromosome 15q13.3

Our data support associations of schizophrenia with 1.5-Mb deletions containing ARHGAP11B, MTMR15, MTMR10, TRPM1, KLF13, OTUD7A, and CHRNA7. Duplications were observed in seven schizophrenia patients in MGS and ISC and two comparison subjects (p=0.11). Shorter CNVs in the region are not associated with schizophrenia. Case subjects with these deletions reported more seizures, but clinical details are not available. For both long and short exonic deletions, the ratio of their occurrence in the case and comparison subjects was 35:20 for CHRNA7 and 30:17 for ARHGAP11B, higher (7:1 to 10:2) for the other five genes, and highest in OTUD7A (8:1), which codes for a deubiquitinating enzyme.

Chromosome 16p11.2

This is the one region where different copy numbers are more strongly associated with schizophrenia (duplications) than with autism (deletions) (3). In children, deletions produce macrocephaly and behavioral problems, including autism; duplications produce microcephaly and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder; and neurodevelopmental delays, learning disorders, congenital anomalies, and seizures occur in both groups (26). Our case subjects reported more learning problems and seizures. The region contains 26 annotated genes (SPN to CORO1A) plus three genes duplicated in each flanking segmental duplication region (see Table S7).

Exonic Deletions in NRXN1

Neurexin-1 is a presynaptic neuronal cell surface molecule that participates with postsynaptic neuroligins in cell adhesion and synaptic signaling. Neurexin and neuroligin mutations have been implicated in autism, and mice with NRXN1 deletions have deficient prepulse inhibition, a schizophrenia endophenotype (27). Diverse CNVs are seen in this 1.1-Mb-long gene. Association of rare exonic NRXN1 deletions, reported by Rujescu et al. (5) and supported by a meta-analysis (4), is strongly confirmed here. Exonic duplications were observed in only two MGS and ISC case subjects and in no comparison subjects. Deletions of specific exons and/or regulatory regions may be critical, given the approximately 1,000 alternative splicings producing proteins. The patients with NRXN1 deletions reported more learning problems and seizures, consistent with observations of deletions in mental retardation and of homozygous deletions in the Pitt-Hopkins syndrome of mental retardation and epilepsy (28). Pitt-Hopkins syndrome is also caused by mutations in TCF4, in which common SNPs are associated with schizophrenia (29). Owing to the strong association of exonic NRXN1 deletions with schizophrenia and to the large effect size, this appears to be the first single gene that has been shown to be involved in the etiology of schizophrenia.

Chromosome 22q11.21

Our findings here are consistent with previous reports. We observed 19 longer deletions, typically 3.5 Mb (from 17,256,428 to 19,795,835 bp), and two shorter (1.4–2.0 Mb) proximal deletions (spanning 43 and 29 genes, respectively) (Table S7). An additional case subject (not counted in this analysis) had a 760-kb distal deletion of unknown significance (19,035,775 to 19,795,835 bp), not previously reported in schizophrenia nor overlapping the proximal deletions. There are no robust SNP association findings within these genes (12). Our case subjects with 22q11.21 deletions reported more learning problems, seizures, and thyroid problems (seen in DiGeorge syndrome) than did those with no CNVs. We observed deletions in 0.53% of the case subjects, 18 (0.67%) of European ancestry and three (0.23%) African American. Velocardiofacial syndrome is associated with early mortality (30). The African American patients with deletions in this region were all under age 45, but deletions were seen in 0.35% and 0.65% of the case subjects of European ancestry under and over age 40; the age at interview did not differ between the two ethnic groups. It is unclear why there were no older African American patients, but the prevalence in the patients with European ancestry (0.67%) does not seem to have been underestimated because of early mortality.

Chromosome 3q29

These 1.6-Mb deletions were observed in five MGS and two ISC case subjects and no comparison subjects. They are identical to the 3q29 microdeletions reported to cause mild-moderate mental retardation, microcephaly in half of patients, autism in a minority, and inconsistent physical anomalies (31). Reciprocal duplications (not observed here) are also associated with mental retardation and microcephaly. Two of the five MGS case subjects (one reporting seizures in infancy) received consensus diagnoses of definite or possible mild mental retardation, and a third attributed seizures to a drug reaction. Walsh et al. (8) reported one similar deletion in a schizophrenia subject in a group of 150. After this article was submitted, Mulle et al. (17) reported an association between schizophrenia and 3q29 deletions on the basis of one 836-kb deletion in an Ashkenazi group and five longer deletions: the one reported by Walsh et al., the two ISC case subjects included in Table 2, and two MGS case subjects from the Genetic Association Information Network data set available from the Database of Genotypes and Phenotypes (dbGaP) (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/gap). We have not added the Ashkenazi data to our analysis because all of the other reported deletions in case subjects cover the full 1.6-Mb region, and it is unknown whether 800-kb deletions are associated with schizophrenia; seven short exonic DLG1 deletions were observed in the MGS and Philadelphia comparison subjects.

The 1.6-Mb deletion spans 21 genes (TFRC to BDH1, Table S7). PAK2 and DLG1 are homologues of X-linked mental retardation genes PAK3 and DLG3 (listed as OMIM 300142 and OMIM 300189, respectively, in the Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man [OMIM] catalog; http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/omim). Expression of DLG1 (also known as SAP97) was lower than normal in postmortem prefrontal cortex from individuals with schizophrenia (32). (Exonic deletions in the homologue DLG2 were seen in four MGS case subjects and no comparison subjects, in two ISC case subjects and one comparison subject, and in one Philadelphia comparison subject assessed with the Illumina 550K microarray.) Other plausible candidates include MFI2, which shows high expression in amyloid plaques (33); PCYT1A (choline-phosphate cytidylyltransferase A), which controls synthesis of the phosphoplipid phosphatidylcholine, itself hypothesized to play a role in schizophrenia (34); Tnk2, a tyrosine kinase involved in adult synaptic function and plasticity and in brain development; TM4SF19, involved in cell fusion and signaling and related to TM4SF2/A15, which is associated with mental retardation (35); FBXO45, a ubiquitin ligase involved in regulation of synaptic activity, neuronal migration, and patterning of neuronal connectivity; and PIGX/PIGZ, involved in biosynthesis of glycosylphosphatidylinositol, which anchors cell adhesion molecules and other proteins to the plasma membrane.

VIPR2

Exonic VIPR2 duplications were associated with schizophrenia with an odds ratio of 4.0, with consistency observed across MGS (10:2 case:control ratio), ISC (4:0), and the Philadelphia comparison group (five of 8,029). The MGS case subjects had high ratings for positive symptoms. VIPR2 encodes a receptor for vasoactive intestinal peptide and pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating polypeptide, peptides with diverse roles in embryonic neural development, neuroprotection and response to neural injury, and inflammatory processes. Both have been hypothesized to have roles in autism (10) and schizophrenia (11).

Other Findings

The strongest evidence for association (p=0.002 in MGS; p=0.0001 overall, including Philadelphia comparison subjects assessed with the Illumina 610K array; odds ratio=12.9) was observed for exonic duplications in C16orf72, a brain-expressed gene of unknown function. More data are needed to evaluate this region because of the diverse size range and the small number of probes on the Illumina arrays (we excluded data for the 550K array, which had only three probes). Other genes and regions shown in Table 2 are also plausible candidates: AGTPBP1, encoding the zinc carboxypeptidase NNA1 (nervous system nuclear protein induced by axotomy); NEDD4L (neural precursor cell expressed, developmentally down-regulated 4-like), a ubiquitin-protein ligase involved in inhibition of beta tumor growth factor (TGF-β) signaling and ubiquitination of several plasma membrane channels; and GLB1L3 and GLB1L2, two forms of beta-galactosidase; neurodegeneration is a major feature of the recessive GM1 gangliosidosis caused by homozygous GLB1 mutations. We noted four large duplications in CSMD3 in case subjects and none in comparison subjects (but the ratio was 3:2 in ISC); two patients with translocation breakpoints near CSMD3 had autistic behavior and developmental delay (36). The GWAS of the MGS subjects of European ancestry produced moderate evidence for an association of schizophrenia with the paralogue CSMD1 (4.45 × 10−5) (12).

Genome-Wide CNV Count

The case subjects had more large deletions (but not duplications) in the affected genes or exons, suggesting that additional associations will be discovered in larger data sets. Some CNVs may be too rare for association to be proven. The observed increase is modest and might explain a few more percent of schizophrenia cases.

Conclusions and Implications for Future Research

Microarrays have detected rare CNVs that substantially increase the risk of neuropsychiatric disorders. Although these CNVs explain only a small portion of schizophrenia risk in the population, fundamental discoveries could result from efforts to explain the biological mechanisms underlying the association of these CNVs with schizophrenia, autism, mental retardation, and epilepsy and perhaps from SNP associations with similar phenotypic overlap or biological mechanisms. It is not yet clear whether these mechanisms are relevant to most cases of schizophrenia, given that many susceptibility genes might be located in regions not prone to CNVs and thus not detectable by CNV scans; however, carriers of associated CNVs had typical clinical features similar to those in the rest of a large study group. We note that several schizophrenia-associated CNVs produce microcephaly, including 1q21.1 deletions (with duplications associated with macrocephaly), possibly related to HYDIN; 3q29 deletions, possibly related to PAK2 and/or DLG1; and 16p11.2 duplications.

The strong evidence for the association of NRXN1 with schizophrenia provides clear impetus for research into related neurodevelopmental and neural signaling processes. CNVs in VIPR2 or other genes could provide additional clues. The 1q, 3q29, 15q, 16p, and 22q CNVs involve many genes. While it has been hoped that shorter CNVs would provide clues as to which genes were critical to the association, we note several regions where shorter CNVs in obvious candidate genes (such as CHRNA7 in 15q13.3 or DLG1 in 3q29) have much lower odds ratios than the long CNVs. It is possible that pathogenic effects are due to the CNV’s effects on combinations of genes within or (through expression changes) outside its boundaries, perhaps interacting with genotypes on the patient’s intact or duplicated chromosome.

Some have argued that the association of rare CNVs with schizophrenia demonstrates that much of the risk for this disease will be explained by high-penetrance rare variants (37). However, it is not yet clear how many rare SNPs or small insertions/deletions will be as pathogenic as are these long, multigenic CNVs. Whole-genome sequencing is likely to produce additional surprises about the genomic basis of disease risk.

We would also urge caution about the use of high-penetrance CNVs as presymptomatic tests for schizophrenia (e.g., prenatally or in infants or children). If approximately 1% of 300,000,000 Americans will develop broadly defined schizophrenia, our data suggest that 1.25% (37,500) will carry one of the CNVs listed in Table 3, as will 0.09% (270,000) of individuals who never develop schizophrenia (possibly an underestimate if, as we suspect, individuals with mild learning or other neuropsychiatric problems are underrepresented in comparison groups) (38). Thus, we do not know the true proportions of carriers with severe, mild, or no neuropsychiatric disorder, and the overall positive predictive value for schizophrenia may be 12% or less.

We are reaching the point, however, where CNV testing could be indicated for individuals with schizophrenia. Several strongly associated CNVs have implications for clinical management and pre-conception reproductive counseling of patients. For example, a higher rate of premature death was observed in patients with 22q11.2 deletion, even those without congenital heart disease or schizophrenia (39). Among 558 adults (mean age, 34.7 years) with tetralogy of Fallot or pulmonary atresia, 24 (54%) of 44 with 22q11.2 deletions discovered by screening had not previously been diagnosed (40), and aortic root dilation has been detected in 22q11.2 patients without other cardiac anomalies (41). There are other medical features, as well as a specific mathematical learning disability that is relevant to rehabilitation and vocational planning (42). The development of cost-effective clinical assays for known CNVs would be valuable for these patients.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Dr. Black has received research support from AstraZeneca and Forest Laboratories; he is also a shareholder with Johnson and Johnson.

Molecular Genetics of Schizophrenia data collection was supported by NIMH R01 grants MH-67257 to Ms. Buccola, MH-59588 to Dr. Mowry, MH-59571 and MH-81800 to Dr. Gejman, MH-59565 to Dr. Freedman, MH-59587 to Dr. Amin, MH-60870 to Dr. Byerley, MH-59566 to Dr. Black, MH-59586 to Dr. Silverman, MH-61675 to Dr. Levinson, and MH-60879 to Dr. Cloninger and by NIMH U01 grants MH-46276 to Dr. Cloninger, MH-46289 to C. Kaufmann, and MH-46318 to M.T. Tsuang. The GWAS study was supported by NIMH U01 grants MH-79469 to Dr. Gejman and MH-79470 to Dr. Levinson. Support was also received from National Alliance for Research on Schizophrenia and Depression Young Investigator Awards to Dr. Duan and Dr. Sanders, the Genetic Association Information Network (GAIN), the Paul Michael Donovan Charitable Foundation, and the Walter E. Nichols, M.D., and Eleanor Nichols endowments (Stanford University). Genotyping was carried out by the Center for Genotyping and Analysis at the Broad Institute of Harvard and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (S. Gabriel and D.B. Mirel) with support from grant U54 RR-020278 from the National Center for Research Resources. Genotyping of half of the European American study group and almost all the African American group was carried out with support from GAIN.

The authors thank the study participants, the research staff at the study sites, the GAIN quality control team (G.R. Abecasis and J. Paschall), S. Purcell for assistance with PLINK, Knowledge Networks, Inc., for recruiting the comparison group, and Dr. Steve McCarroll, Josh Korn, and Alec Wysoker for assistance with Birdsuite.

Clinical information, genotypes, fluorescent intensity values, and biological materials are available to qualified investigators through the NIMH repository program (http://nimhgenetics.org). The authors will provide Database of Genotypes and Phenotypes (dbGAP) IDs corresponding to individual CNVs reported here to investigators with dbGAP access approval.

Footnotes

Presented at the 18th World Congress of Psychiatric Genetics, Athens, Greece, Oct. 3–7, 2010, and the 60th annual meeting of the American Society of Human Genetics, Washington, D.C., Nov. 2–6, 2010.

The other authors report no financial relationships with commercial interests.

References

- 1.Stefansson H, Rujescu D, Cichon S, Pietilainen OP, Ingason A, Steinberg S, Fossdal R, Sigurdsson E, Sigmundsson T, Buizer-Voskamp JE, Hansen T, Jakobsen KD, Muglia P, Francks C, Matthews PM, Gylfason A, Halldorsson BV, Gudbjartsson D, Thorgeirsson TE, Sigurdsson A, Jonasdottir A, Jonasdottir A, Bjornsson A, Mattiasdottir S, Blondal T, Haraldsson M, Magnusdottir BB, Giegling I, Moller HJ, Hartmann A, Shianna KV, Ge D, Need AC, Crombie C, Fraser G, Walker N, Lonnqvist J, Suvisaari J, Tuulio-Henriksson A, Paunio T, Toulopoulou T, Bramon E, Di Forti M, Murray R, Ruggeri M, Vassos E, Tosato S, Walshe M, Li T, Vasilescu C, Muhleisen TW, Wang AG, Ullum H, Djurovic S, Melle I, Olesen J, Kiemeney LA, Franke B, Sabatti C, Freimer NB, Gulcher JR, Thorsteinsdottir U, Kong A, Andreassen OA, Ophoff RA, Georgi A, Rietschel M, Werge T, Petursson H, Goldstein DB, Nothen MM, Peltonen L, Collier DA, St Clair D, Stefansson K. Large recurrent microdeletions associated with schizophrenia. Nature. 2008;455:232–236. doi: 10.1038/nature07229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.International Schizophrenia Consortium: Rare chromosomal deletions and duplications increase risk of schizophrenia. Nature. 2008;455:237–241. doi: 10.1038/nature07239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McCarthy SE, Makarov V, Kirov G, Addington AM, McClellan J, Yoon S, Perkins DO, Dickel DE, Kusenda M, Krastoshevsky O, Krause V, Kumar RA, Grozeva D, Malhotra D, Walsh T, Zackai EH, Kaplan P, Ganesh J, Krantz ID, Spinner NB, Roccanova P, Bhandari A, Pavon K, Lakshmi B, Leotta A, Kendall J, Lee YH, Vacic V, Gary S, Iakoucheva LM, Crow TJ, Christian SL, Lieberman JA, Stroup TS, Lehtimaki T, Puura K, Haldeman-Englert C, Pearl J, Goodell M, Willour VL, Derosse P, Steele J, Kassem L, Wolff J, Chitkara N, McMahon FJ, Malhotra AK, Potash JB, Schulze TG, Nothen MM, Cichon S, Rietschel M, Leibenluft E, Kustanovich V, Lajonchere CM, Sutcliffe JS, Skuse D, Gill M, Gallagher L, Mendell NR, Craddock N, Owen MJ, O’Donovan MC, Shaikh TH, Susser E, Delisi LE, Sullivan PF, Deutsch CK, Rapoport J, Levy DL, King MC, Sebat J. Microduplications of 16p11.2 are associated with schizophrenia. Nat Genet. 2009;41:1223–1227. doi: 10.1038/ng.474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kirov G, Rujescu D, Ingason A, Collier DA, O’Donovan MC, Owen MJ. Neurexin 1 (NRXN1) deletions in schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 2009;35:851–854. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbp079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rujescu D, Ingason A, Cichon S, Pietilainen OP, Barnes MR, Toulopoulou T, Picchioni M, Vassos E, Ettinger U, Bramon E, Murray R, Ruggeri M, Tosato S, Bonetto C, Steinberg S, Sigurdsson E, Sigmundsson T, Petursson H, Gylfason A, Olason PI, Hardarsson G, Jonsdottir GA, Gustafsson O, Fossdal R, Giegling I, Moller HJ, Hartmann AM, Hoffmann P, Crombie C, Fraser G, Walker N, Lonnqvist J, Suvisaari J, Tuulio-Henriksson A, Djurovic S, Melle I, Andreassen OA, Hansen T, Werge T, Kiemeney LA, Franke B, Veltman J, Buizer-Voskamp JE, Sabatti C, Ophoff RA, Rietschel M, Nothen MM, Stefansson K, Peltonen L, St Clair D, Stefansson H, Collier DA. Disruption of the neurexin 1 gene is associated with schizophrenia. Hum Mol Genet. 2009;18:988–996. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddn351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bassett AS, Scherer SW, Brzustowicz LM. Copy number variations in schizophrenia: critical review and new perspectives on concepts of genetics and disease. Am J Psychiatry. 2010;167:899–914. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2009.09071016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kirov G, Grozeva D, Norton N, Ivanov D, Mantripragada KK, Holmans P, Craddock N, Owen MJ, O’Donovan MC. Support for the involvement of large copy number variants in the pathogenesis of schizophrenia. Hum Mol Genet. 2009;18:1497–1503. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddp043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Walsh T, McClellan JM, McCarthy SE, Addington AM, Pierce SB, Cooper GM, Nord AS, Kusenda M, Malhotra D, Bhandari A, Stray SM, Rippey CF, Roccanova P, Makarov V, Lakshmi B, Findling RL, Sikich L, Stromberg T, Merriman B, Gogtay N, Butler P, Eckstrand K, Noory L, Gochman P, Long R, Chen Z, Davis S, Baker C, Eichler EE, Meltzer PS, Nelson SF, Singleton AB, Lee MK, Rapoport JL, King MC, Sebat J. Rare structural variants disrupt multiple genes in neurodevelopmental pathways in schizophrenia. Science. 2008;320:539–543. doi: 10.1126/science.1155174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Willatt L, Cox J, Barber J, Cabanas ED, Collins A, Donnai D, Fitz-Patrick DR, Maher E, Martin H, Parnau J, Pindar L, Ramsay J, Shaw-Smith C, Sistermans EA, Tettenborn M, Trump D, de Vries BB, Walker K, Raymond FL. 3q29 microdeletion syndrome: clinical and molecular characterization of a new syndrome. Am J Hum Genet. 2005;77:154–160. doi: 10.1086/431653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hill JM. Vasoactive intestinal peptide in neurodevelopmental disorders: therapeutic potential. Curr Pharm Des. 2007;13:1079–1089. doi: 10.2174/138161207780618975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hashimoto R, Hashimoto H, Shintani N, Chiba S, Hattori S, Okada T, Nakajima M, Tanaka K, Kawagishi N, Nemoto K, Mori T, Ohnishi T, Noguchi H, Hori H, Suzuki T, Iwata N, Ozaki N, Nakabayashi T, Saitoh O, Kosuga A, Tatsumi M, Kamijima K, Weinberger DR, Kunugi H, Baba A. Pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating polypeptide is associated with schizophrenia. Mol Psychiatry. 2007;12:1026–1032. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shi J, Levinson DF, Duan J, Sanders AR, Zheng Y, Pe’er I, Dudbridge F, Holmans PA, Whittemore AS, Mowry BJ, Olincy A, Amin F, Cloninger CR, Silverman JM, Buccola NG, Byerley WF, Black DW, Crowe RR, Oksenberg JR, Mirel DB, Kendler KS, Freedman R, Gejman PV. Common variants on chromosome 6p22.1 are associated with schizophrenia. Nature. 2009;460:753–757. doi: 10.1038/nature08192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shaikh TH, Gai X, Perin JC, Glessner JT, Xie H, Murphy K, O’Hara R, Casalunovo T, Conlin LK, D’Arcy M, Frackelton EC, Geiger EA, Haldeman-Englert C, Imielinski M, Kim CE, Medne L, Annaiah K, Bradfield JP, Dabaghyan E, Eckert A, Onyiah CC, Ostapenko S, Otieno FG, Santa E, Shaner JL, Skraban R, Smith RM, Elia J, Goldmuntz E, Spinner NB, Zackai EH, Chiavacci RM, Grundmeier R, Rappaport EF, Grant SF, White PS, Hakonarson H. High-resolution mapping and analysis of copy number variations in the human genome: a data resource for clinical and research applications. Genome Res. 2009;19:1682–1690. doi: 10.1101/gr.083501.108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang K, Li M, Hadley D, Liu R, Glessner J, Grant SF, Hakonarson H, Bucan M. PennCNV: an integrated hidden Markov model designed for high-resolution copy number variation detection in whole-genome SNP genotyping data. Genome Res. 2007;17:1665–1674. doi: 10.1101/gr.6861907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Korn JM, Kuruvilla FG, McCarroll SA, Wysoker A, Nemesh J, Cawley S, Hubbell E, Veitch J, Collins PJ, Darvishi K, Lee C, Nizzari MM, Gabriel SB, Purcell S, Daly MJ, Altshuler D. Integrated genotype calling and association analysis of SNPs, common copy number polymorphisms and rare CNVs. Nat Genet. 2008;40:1253–1260. doi: 10.1038/ng.237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lai TL, Xing H, Zhang N. Stochastic segmentation models for array-based comparative genomic hybridization data analysis. Biostatistics. 2008;9:290–307. doi: 10.1093/biostatistics/kxm031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mulle JG, Dodd AF, McGrath JA, Wolyniec PS, Mitchell AA, Shetty AC, Sobreira NL, Valle D, Rudd MK, Satten G, Cutler DJ, Pulver AE, Warren ST. Microdeletions of 3q29 confer high risk for schizophrenia. Am J Hum Genet. 2010;87:229–236. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2010.07.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Purcell S, Neale B, Todd-Brown K, Thomas L, Ferreira MA, Bender D, Maller J, Sklar P, de Bakker PI, Daly MJ, Sham PC. PLINK: a tool set for whole-genome association and population-based linkage analyses. Am J Hum Genet. 2007;81:559–575. doi: 10.1086/519795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Agresti A. Categorical Data Analysis, 2nd ed. New York: John Wiley & Sons; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Weiss LA, Shen Y, Korn JM, Arking DE, Miller DT, Fossdal R, Saemundsen E, Stefansson H, Ferreira MAR, Green T, Platt OS, Ruderfer DM, Walsh CA, Altshuler D, Chakravarti A, Tanzi RE, Stefansson K, Santangelo SL, Gusella JF, Sklar P, Wu B-L, Daly MJ Autism Consortium. Association between microdeletion and microduplication at 16p11.2 and autism. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:667–675. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa075974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Need AC, Ge D, Weale ME, Maia J, Feng S, Heinzen EL, Shianna KV, Yoon W, Kasperaviciute D, Gennarelli M, Strittmatter WJ, Bonvicini C, Rossi G, Jayathilake K, Cola PA, McEvoy JP, Keefe RS, Fisher EM, St Jean PL, Giegling I, Hartmann AM, Moller HJ, Ruppert A, Fraser G, Crombie C, Middleton LT, St Clair D, Roses AD, Muglia P, Francks C, Rujescu D, Meltzer HY, Goldstein DB. A genome-wide investigation of SNPs and CNVs in schizophrenia. PLoS Genet. 2009;5(2):e1000373. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ikeda M, Aleksic B, Kirov G, Kinoshita Y, Yamanouchi Y, Kitajima T, Kawashima K, Okochi T, Kishi T, Zaharieva I, Owen MJ, O’Donovan MC, Ozaki N, Iwata N. Copy number variation in schizophrenia in the Japanese population. Biol Psychiatry. 2010;67:283–286. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.08.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Levinson DF, Mowry BJ, Escamilla MA, Faraone SV. The Lifetime Dimensions of Psychosis Scale (LDPS): description and interrater reliability. Schizophr Bull. 2002;28:683–695. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a006972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kirov G, Gumus D, Chen W, Norton N, Georgieva L, Sari M, O’Donovan MC, Erdogan F, Owen MJ, Ropers HH, Ullmann R. Comparative genome hybridization suggests a role for NRXN1 and APBA2 in schizophrenia. Hum Mol Genet. 2008;17:458–465. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddm323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Brunetti-Pierri N, Berg JS, Scaglia F, Belmont J, Bacino CA, Sahoo T, Lalani SR, Graham B, Lee B, Shinawi M, Shen J, Kang SH, Pursley A, Lotze T, Kennedy G, Lansky-Shafer S, Weaver C, Roeder ER, Grebe TA, Arnold GL, Hutchison T, Reimschisel T, Amato S, Geragthy MT, Innis JW, Obersztyn E, Nowakowska B, Rosengren SS, Bader PI, Grange DK, Naqvi S, Garnica AD, Bernes SM, Fong CT, Summers A, Walters WD, Lupski JR, Stankiewicz P, Cheung SW, Patel A. Recurrent reciprocal 1q21.1 deletions and duplications associated with microcephaly or macrocephaly and developmental and behavioral abnormalities. Nat Genet. 2008;40:1466–1471. doi: 10.1038/ng.279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shinawi M, Liu P, Kang SH, Shen J, Belmont JW, Scott DA, Probst FJ, Craigen WJ, Graham B, Pursley A, Clark G, Lee J, Proud M, Stocco A, Rodriguez D, Kozel B, Sparagana S, Roeder E, McGrew S, Kurczynski T, Allison L, Amato S, Savage S, Patel A, Stankiewicz P, Beaudet A, Cheung SW, Lupski JR. Recurrent reciprocal 16p11.2 rearrangements associated with global developmental delay, behavioral problems, dysmorphism, epilepsy, and abnormal head size. J Med Genet. 2009;47:332–341. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2009.073015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Etherton MR, Blaiss CA, Powell CM, Sudhof TC. Mouse neurexin-1alpha deletion causes correlated electrophysiological and behavioral changes consistent with cognitive impairments. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:17998–18003. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0910297106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zweier C, de Jong EK, Zweier M, Orrico A, Ousager LB, Collins AL, Bijlsma EK, Oortveld MA, Ekici AB, Reis A, Schenck A, Rauch A. CNTNAP2 and NRXN1 are mutated in autosomal-recessive Pitt-Hopkins-like mental retardation and determine the level of a common synaptic protein in Drosophila. Am J Hum Genet. 2009;85:655–666. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2009.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stefansson H, Ophoff RA, Steinberg S, Andreassen OA, Cichon S, Rujescu D, Werge T, Pietilainen OP, Mors O, Mortensen PB, Sigurdsson E, Gustafsson O, Nyegaard M, Tuulio-Henriksson A, Ingason A, Hansen T, Suvisaari J, Lonnqvist J, Paunio T, Borglum AD, Hartmann A, Fink-Jensen A, Nordentoft M, Hougaard D, Norgaard-Pedersen B, Bottcher Y, Olesen J, Breuer R, Moller HJ, Giegling I, Rasmussen HB, Timm S, Mattheisen M, Bitter I, Rethelyi JM, Magnusdottir BB, Sigmundsson T, Olason P, Masson G, Gulcher JR, Haraldsson M, Fossdal R, Thorgeirsson TE, Thorsteinsdottir U, Ruggeri M, Tosato S, Franke B, Strengman E, Kiemeney LA, Genetic Risk and Outcome in Psychosis (GROUP) Melle I, Djurovic S, Abramova L, Kaleda V, Sanjuan J, de Frutos R, Bramon E, Vassos E, Fraser G, Ettinger U, Picchioni M, Walker N, Toulopoulou T, Need AC, Ge D, Lim Yoon J, Shianna KV, Freimer NB, Cantor RM, Murray R, Kong A, Golimbet V, Carracedo A, Arango C, Costas J, Jonsson EG, Terenius L, Agartz I, Petursson H, Nothen MM, Rietschel M, Matthews PM, Muglia P, Peltonen L, St Clair D, Goldstein DB, Stefansson K, Collier DA, Kahn RS, Linszen DH, van Os J, Wiersma D, Bruggeman R, Cahn W, de Haan L, Krabbendam L, Myin-Germeys I. Common variants conferring risk of schizophrenia. Nature. 2009;460:744–747. doi: 10.1038/nature08186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bassett AS, Chow EW. Schizophrenia and 22q11.2 deletion syndrome. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2008;10:148–157. doi: 10.1007/s11920-008-0026-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ballif BC, Theisen A, Coppinger J, Gowans GC, Hersh JH, Madan-Khetarpal S, Schmidt KR, Tervo R, Escobar LF, Friedrich CA, Mc-Donald M, Campbell L, Ming JE, Zackai EH, Bejjani BA, Shaffer LG. Expanding the clinical phenotype of the 3q29 microdeletion syndrome and characterization of the reciprocal microduplication. Mol Cytogenet. 2008;1:8. doi: 10.1186/1755-8166-1-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Toyooka K, Iritani S, Makifuchi T, Shirakawa O, Kitamura N, Maeda K, Nakamura R, Niizato K, Watanabe M, Kakita A, Takahashi H, Someya T, Nawa H. Selective reduction of a PDZ protein, SAP-97, in the prefrontal cortex of patients with chronic schizophrenia. J Neurochem. 2002;83:797–806. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2002.01181.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jefferies WA, Food MR, Gabathuler R, Rothenberger S, Yamada T, Yasuhara O, McGeer PL. Reactive microglia specifically associated with amyloid plaques in Alzheimer’s disease brain tissue express melanotransferrin. Brain Res. 1996;712:122–126. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(95)01407-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schwarz E, Prabakaran S, Whitfield P, Major H, Leweke FM, Koethe D, McKenna P, Bahn S. High throughput lipidomic profiling of schizophrenia and bipolar disorder brain tissue reveals alterations of free fatty acids, phosphatidylcholines, and ceramides. J Proteome Res. 2008;7:4266–4277. doi: 10.1021/pr800188y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zemni R, Bienvenu T, Vinet MC, Sefiani A, Carrie A, Billuart P, McDonell N, Couvert P, Francis F, Chafey P, Fauchereau F, Friocourt G, des Portes V, Cardona A, Frints S, Meindl A, Brandau O, Ronce N, Moraine C, van Bokhoven H, Ropers HH, Sudbrak R, Kahn A, Fryns JP, Beldjord C, Chelly J. A new gene involved in X-linked mental retardation identified by analysis of an X;2 balanced translocation. Nat Genet. 2000;24:167–170. doi: 10.1038/72829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Floris C, Rassu S, Boccone L, Gasperini D, Cao A, Crisponi L. Two patients with balanced translocations and autistic disorder: CSMD3 as a candidate gene for autism found in their common 8q23 breakpoint area. Eur J Hum Genet. 2008;16:696–704. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2008.7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Need AC, Goldstein DB. Whole genome association studies in complex diseases: where do we stand? Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2010;12:37–46. doi: 10.31887/DCNS.2010.12.1/aneed. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sanders AR, Levinson DF, Duan J, Dennis JM, Li R, Kendler KS, Rice JP, Shi J, Mowry BJ, Amin F, Silverman JM, Buccola NG, Byerley WF, Black DW, Freedman R, Cloninger CR, Gejman PV. The Internet-based MGS2 control sample: self report of mental illness. Am J Psychiatry. 2010;167:854–865. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2010.09071050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bassett AS, Chow EW, Husted J, Hodgkinson KA, Oechslin E, Harris L, Silversides C. Premature death in adults with 22q11.2 deletion syndrome. J Med Genet. 2009;46:324–330. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2008.063800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.van Engelen K, Topf A, Keavney BD, Goodship JA, van der Velde ET, Baars MJ, Snijder S, Moorman AF, Postma AV, Mulder BJ. 22q11.2 deletion syndrome is under-recognised in adult patients with tetralogy of Fallot and pulmonary atresia. Heart. 2010;96:621–624. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2009.182642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.John AS, McDonald-McGinn DM, Zackai EH, Goldmuntz E. Aortic root dilation in patients with 22q11.2 deletion syndrome. Am J Med Genet A. 2009;149A:939–942. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.32770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.De Smedt B, Swillen A, Verschaffel L, Ghesquiere P. Mathematical learning disabilities in children with 22q11.2 deletion syndrome: a review. Dev Disabil Res Rev. 2009;15:4–10. doi: 10.1002/ddrr.44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.