Abstract

Nonclassical patrolling monocytes are characterized by their unique ability to actively patrol the vascular endothelium under homeostatic and inflammatory conditions. Patrolling monocyte subsets (CX3CR1highLy6C− in mouse, and CX3CR1highCD14dimCD16+ in humans) are distinct from the classical monocyte subsets (CCR2highLy6C+ in mouse, and CCR2highCD14+CD16− in humans) and exhibit unique functions in the vasculature and inflammatory disease. Patrolling monocytes function in a number of disease settings to remove damaged cells and debris from the vasculature, and have been associated with wound healing and the resolution of inflammation in damaged tissues. This review highlights the unique functions of these patrolling monocytes in the vasculature and during inflammation.

Introduction

Monocytes are the primary inflammatory cell type that infiltrates early atherosclerotic plaques 1, and considerable evidence implicates monocytes as critical to the development of atherosclerosis 2–7. Atherosclerotic lesion size correlate strongly with the number of circulating monocytes, and combined inhibition of the monocyte recruitment factors CCL2, CX3CR1 and CCR5 nearly abolishes atherosclerotic development in hypercholesterolemic mice 5. In mouse models of cardiac injury the depletion of monocytes leads to higher mortality and reduced ventricular function, suggesting that monocytes are necessary for proper wound healing and rebuilding of heart tissue 8. Thus, understanding the role of monocyte activities in the vasculature, cardiac injury and inflammatory disease is important to understanding the etiology of cardiovascular disease and potential therapeutic targeting of monocyte activities.

Currently three types of monocytes have been defined in humans and in mice 9–14. Monocytes are characterized in humans by their positive expression of HLA-DR, CD11b, and differential expression of CD14 and CD16, and in mice by their positive expression of CD115 and CD11b, and differential expression of Ly6C and CD43. “Classical” monocytes (CD14+CD16− in humans, and Ly6C+CD43− in mouse) express high levels of the chemokine receptor CCR2 and can migrate to sites of injury and infection where they differentiate into inflammatory macrophages 9, 15. In contrast, “nonclassical” monocytes (CD14dimCD16+ in humans, and Ly6C−CD43+ in mouse) have high levels of the adhesion related receptor CX3CR1 and exhibit a unique ability to patrol the resting vasculature and remove debris 16, 17. In addition, a 3rd subset of “intermediate” monocytes (CD14+CD16+ in humans, and Ly6C+CD43+ in mouse) have been identified which have high expression of CX3CR1, but generally possess inflammatory characteristics. Some earlier studies in humans grouped CD16+ intermediate monocytes with CD14dimCD16+ nonclassical patrolling monocytes, though current evidence suggests that intermediate monocytes are distinct and do not actively patrol the vasculature 10.

Nonclassical monocytes actively and continuously patrol the luminal side of the vascular endothelium both at steady state and during inflammation. Monocyte patrolling has been observed in the small blood veins and arteries of the dermis, mesentery, lung, and brain 10, 17, 18. However, these cells are not restricted to the vasculature as nonclassical monocytes also undergo diadepesis and are found within atherosclerotic plaques, as well as within the parenchyma of multiple other tissues 15, 19–21. This review focuses on the differentiation, recruitment, regulation, and physiological functions of “nonclassical” patrolling monocytes in the vasculature and in inflammatory diseases.

Patrolling monocyte development

Monocytes are short-lived mononuclear phagocytes that are continuously replaced throughout life from a common committed progenitor. In mice, monocytes mostly live only two days in circulation in the absence of inflammation, but a small fraction can live seven days or more 22. Nonclassical Ly6C− monocytes are generally longer lived than classical Ly6C+ monocytes 23. In the absence of classical Ly6C+ monocytes, the half-life of nonclassical Ly6C− monocytes is increased from around 2.5 days to 11 days suggesting an increased surveillance function of nonclassical patrolling monocytes in the vasculature when the classical monocyte population has been disrupted or recruited to inflammatory sites 23.

Monocytes develop predominantly in the bone marrow from a CD117+CD115+CX3CR1+ monocyte dendritic cell precursor (MDP) that also gives rise to splenic dendritic cells 24. Recently a common monocyte progenitor (cMoP) subset of the MDP was described that has potential to produce both monocyte subsets but not dendritic cells, and are defined as CD117+CD115+Ly6C+Flt3− 25. A number of studies support the notion that Ly6C+ monocytes give rise to Ly6C− monocytes. BrdU pulse chase studies have shown rapid incorporation of the thymidine analogue into the DNA of Ly6C+ monocytes followed by a gradual displacement of the Ly6C+ population by Ly6C− monocytes in the BrdU labeled fraction 23. Adoptive transfer studies have shown that congenically labeled Ly6C+ monocytes give rise to Ly6C− monocytes 1–3 days post transfer 21, 23, 25, 26. Corresponding studies of human monocyte subset differentiation and lifespan have yet to be conducted.

Ly6C+ monocytes can give rise to Ly6C− monocytes in vivo, however this does not exclude the existence of an alternative route for Ly6C− monocytes development independent of the Ly6C+ population. Indeed, genetic evidence for this proposal exists. Two myeloid determining transcription factors, IRF8 or KLF4, both specifically regulate Ly6C+ monocyte production without effecting Ly6C− monocyte numbers. Studies of either global IRF8−/− mice, or fetal liver transplant of KLF4−/− cells into irradiated wild type recipients, both report dramatically reduced numbers of Ly6C+ monocytes in the BM while retaining relatively normal Ly6C− monocyte numbers27, 28. These findings imply a pathway for Ly6C− monocyte development that is independent of Ly6C+ monocytes, perhaps originating directly from the cMoP precursor. However, other explanations for this phenotype include the enhanced survival of Ly6C− monocytes in these models. Therefore it remains possible that Ly6C− monocytes derive from either blood or bone marrow Ly6C+ monocytes, from an independent bone marrow monocyte progenitor, or from a combination of all three of these scenarios. In order to resolve these issues a detailed understanding of the factors and pathways regulating the development and survival of both Ly6C+ and Ly6C− monocyte populations will be required.

A major advance in our understanding of patrolling nonclassical monocyte differentiation was made with the discovery that the transcription factor Nur77, encoded for by the gene NR4A1, is absolutely required for Ly6C− monocyte development16, 29. Nur77 is highly expressed in patrolling monocytes, and patrolling monocytes are specifically missing in the blood, spleen, and bone marrow of Nur77 knockout mice 29. The few patrolling monocytes remaining in the bone marrow of Nur77 knockout mice are arrested in S phase of the cell cycle and undergo apoptosis, implying that Nur77 functions as a master regulator of the differentiation and survival of nonclassical patrolling monocytes from myeloid progenitors in the bone marrow. Unlike the chemokine receptor-deficient models used to study monocyte function (discussed below), Nur77-deficient mice lack Ly6C− monocytes both in the bone marrow and periphery. In the homologous human CD14dimCD16+ population of patrolling monocytes there is also high Nur77 expression, and likely common function 10, 30.

Mechanisms of monocyte recruitment, adherence, patrolling and survival in the vasculature

Mature classical and nonclassical monocytes must exit the bone marrow into the peripheral circulation in order to perform their duties. The migratory properties of monocytes are facilitated by the actions of chemokines, and both classical and nonclassical monocytes express a different repertoire of chemokine receptors enabling their differential mobilization from the BM and into tissues. Classical monocytes express high levels of CCR2 and migrate from the BM into the vascular circulation in response to its ligands CCL2, CCL7 and CCL12 31–33. Consequently CCR2−/− mice have reduced Ly6C+ monocytes in the periphery, but an increased frequency of Ly6C+ monocytes in bone marrow, whereas the distribution of Ly6C− monocytes in these mice is relatively normal.

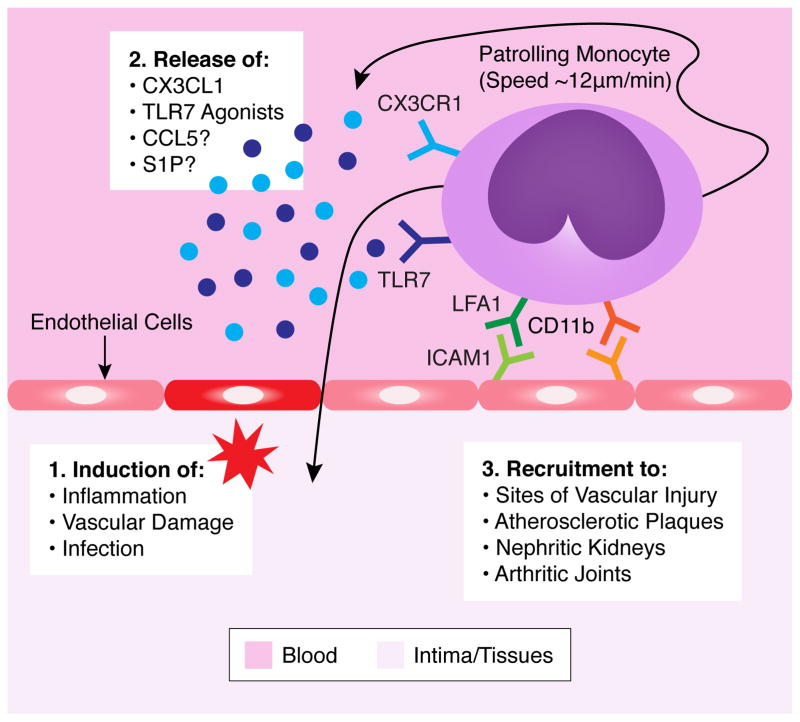

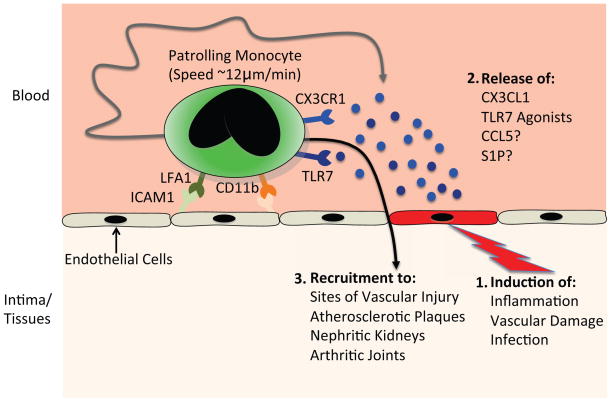

Less is known about the molecular pathways governing the emigration of nonclassical monocytes from the bone marrow and their recruitment to sites of vascular damage or inflammation (See figure 1). Ly6C− monocytes are recruited to sites of atherosclerosis, which was reduced ~40% with CCR5 blockade, suggesting that CCR5 expression is at least partially responsible for nonclassical monocyte recruitment 19. However, CCR5 expression is found at low levels on patrolling monocytes putting into question if this recruitment is directly acting on patrolling monocytes. Recent insight on patrolling monocyte recruitment has been gained from functional studies of sphingosine-1-phosphate (S1P) receptors, which are major regulators of leukocyte activation and trafficking. Administration of the S1P agonist FTY720 facilitates the internalization and degradation of S1P receptors and leads to a reduction in monocyte egress from the BM and spleen into the vasculature 34, 35. Localized FTY720 application can selectively enhance recruitment of patrolling monocytes to ischemic vessels in a S1PR3 dependent manner, suggesting S1P can regulate recruitment of patrolling monocytes 36. Furthermore, S1PR5 is highly expressed on patrolling monocytes and is important for their homeostasis. S1PR5−/− mice have greatly reduced blood-circulating and splenic Ly6C− monocytes, but have normal numbers in the bone marrow 37. This effect was attributed to defective cell intrinsic emigration of S1PR5-deficient monocytes from bone marrow, as the survival of intravenously transferred S1PR5-deficient Ly6C− monocytes were comparable to wild type controls.

Figure 1. Patrolling and Recruitment of Nonclassical Monocytes.

Resting nonclassical monocytes actively patrol the vasculature at a speed of ~12μm/min in a manner independent of blood flow. Nonclassical monocyte patrolling requires LFA1 binding with ICAM1 on vascular endothelial cells. Nonclassical monocyte patrolling and activation is also partially CD11b-dependent. In response to inflammation, vascular damage or infection, there is a release of chemoattractant factors from either endothelial cells, damaged tissues or other recruited immune cells that attract patrolling monocytes. These chemoattractant factors include CX3CL1, TLR7 agonists, CCL5 and S1P, which monocytes can respond to via intrinsic expression of cognate receptors CX3CR1, TLR7 and possibly CCR5 or S1PR. Patrolling monocytes are then either recruited locally to sites of vascular injury or can enter areas of inflammation such as atherosclerotic plaques, nephritic kidneys or arthritic joints.

Patrolling monocytes interact with the vascular endothelium via the β2 integrin, lymphocyte function-associated antigen-1 (LFA-1), and the chemokine receptor CX3CR1 17. A pioneering study by Auffrey et al described the characteristic “patrolling” behavior that nonclassical monocytes display on the luminal side of the vascular endothelium 17. Human CD14dim monocytes have also demonstrated patrolling behavior when infused into mice 10. This patrolling is a much slower process (~12μm/min) than the rolling process of classical monocytes and is independent of the direction of blood flow. Since in vivo analysis of patrolling function of monocytes is difficult to assess in humans, the majority of studies examining nonclassical monocyte patrolling function and activities have used mouse models. Patrolling is in part dependent on the expression of LFA-1, which is highly expressed by nonclassical monocytes. Antibody blockade of either subunit of the LFA-1 complex, CD11a or CD18, leads to the rapid and prolonged disassociation of non-classical monocytes from the endothelium in vivo and abolishes patrolling behavior. The LFA-1 ligands ICAM1 and ICAM2 act in a redundant manner to facilitate LFA-1-dependent adhesion. ICAM1/2−/− mice have a greatly reduced frequency of nonclassical monocyte adhesion to the vasculature, which is a phenocopy of the CD11a−/− (ITGAL) mice16. The capacity for other integrin complexes to mediate patrolling has not been shown, however studies to date cannot rule this out. Interestingly neutrophil arrest in the mouse is entirely dependent on LFA-1, whereas human neutrophils utilize both LFA-1 and MAC-1 (ITGAM/CD11b) 38, 39. Whether or not this is also the case in monocyte patrolling is not known. Further, neutrophil arrest requires integrin conformational changes that allow for high affinity binding. This process involves cytoskeletal adaptor proteins Talin-1 and Kindlin-3 40. The requirement for integrin high affinity binding conformational changes in monocyte patrolling as well as the requirement for integrin activating adaptor proteins is not known and will be important to understanding how the process of patrolling takes place.

Both classical and non-classical monocyte subsets express the chemokine receptor CX3CR1, although patrolling monocytes express it at much higher levels 9. CX3CR1high patrolling monocytes respond to CX3CL1 (also known as fractalkine), a chemokine that is expressed in tissues and can be used as an apoptotic cell recognition receptor. CX3CR1 deletion reduces the patrolling of Ly6C− monocytes 17, and recruitment to the spleen during bacterial infection41. CX3CR1 also provides a survival signal to Ly6C− monocytes. CX3CR1−/− mice have fewer circulating Ly6C− monocytes, which has been attributed to reduced monocyte survival resulting from CX3CR1-dependent expression of the anti-apoptotic protein BCL2 42. In this context it is interesting to note that global IL17RA-deficiency leads to a similar reduction in Ly6C− monocyte survival 43, and that BCL2 is an IL17 target gene in fibroblast-like synoviocytes 44. However a causal link between IL17RA-dependent signaling and BCL2 expression in patrolling monocytes has not been established. Although CX3CR1 is dispensable for the initiation of monocyte patrolling, CX3CR1-CX3CL1 interactions stabilize patrolling in a CD11b-dependent manner 16. Specifically, TLR7 agonists mediate an increase in epithelial CX3CL1 expression that led to a direct increase in the retention time of patrolling monocytes at the epithelial surface.

Infection and tissue damage are not the only environmental cues that result in monocyte mobilization. Other physical factors such as exercise and stress have been demonstrated to recruit monocytes into circulation. Exercise leads to a more than a four-fold increase of nonclassical monocytes in the blood 45, 46. This exercise induced increase can be inhibited by β-adrenergic receptors blockade suggesting a catecholamine-dependent mechanism of recruitment 46. Studies have shown that monocytes express β-adrenergic receptors, and rapidly appear in circulation from vascular marginal pools, a process called demargination, in response to catecholamine release 47. Chronic stress also induces a β3-adrenergic receptor dependent increase in monocyte progenitors in bone marrow, and classical monocytes in circulation, promoting atherosclerotic development 48. In addition to their progenitors, monocytes themselves also express β-adrenergic receptors, thus future studies to learn how stress and exercise induced β-adrenergic receptor signaling directly affects monocyte function in the vasculature and atherosclerotic development should be of interest.

Activation activities of patrolling monocytes

Classical monocytes circulate in the bloodstream and respond to inflammatory cues such as microbial products, cytokines and chemokines produced by infected and/or damaged tissue. In the presence of inflammatory stimuli, circulating inflammatory monocytes can quickly extravasate into affected nonlymphoid tissues in a CCR2–CCL2-dependent manner, where they differentiate into macrophage and dendritic cell subsets32. Upon stimulation these monocytes produce inflammatory cytokines such as IL12, NO, TNF-α and IL-1 and can differentiate into TNF-α producing inflammatory macrophages and DCs (Tip-DCs) 49. These responses result in increased immune activation and bacterial clearance, but also significant tissue damage.

Patrolling monocytes, on the other hand, produce only low levels of proinflammatory cytokines in response to bacteria-derived stimuli such as LPS and PAM3CK4 but high levels of anti-inflammatory, and pro-wound healing factors such as IL1 receptor antagonist, IL10R, apolipoproteins ApoA and ApoE, and CXCL16 in studies using CD14dimCD16+ human monocytes 10. Patrolling monocytes express lower levels of CD14 (a TLR4 co-receptor), suggesting a weaker LPS response 50. However, little is known about the ability of patrolling monocytes to extravasate and differentiate into effector macrophage populations in non-homeostatic conditions. Interestingly, murine patrolling monocytes are the first immune cell detected to extravasate into the peritoneum following listeria monocytogenes infection, and produce high levels of TNF α showing that these cells are not always anti-inflammatory counterparts to the proinflammatory classical monocytes 17. In addition, CD16+ human monocyte stimulated with tumor cells showed enhanced production of TNFα, IL12 and NO compared to classical monocytes, suggesting that nonclassical monocytes may be an important subpopulation of monocytes involved in antitumor response 51. Further, both human and murine patrolling monocytes strongly respond to viruses and nucleic acids via a TLR7/8-MEK pathway by producing proinflammatory cytokines like TNFα and IL1β as well as chemokines CCL3, CCL5, and CXCL10 10, 16. Nonclassical monocytes can recruit neutrophils that function to kill damaged or infected cells in response to nucleic acid-derived TLR7-mediated “danger signals” within the vasculature16. TLR7 activation results in intravascular retention of Ly6C− monocytes, and subsequent removal of cellular debris by the retained monocyte. It is not known if other cell types are directly recruited by patrolling monocytes in response to CCL3, CCL5, and CCL10 production, though this is of high interest to the field. In the absence of inflammatory cues, patrolling monocytes scan the vasculature and uptake microparticles along the endothelium. Thus these cells function as “intravascular housekeepers” that scavenge microparticles, remove cellular debris from the vasculature, and can vigorously respond to cell damage and infection. Therefore, it is possible that nonclassical monocytes function as terminally differentiated cells.

In addition to uptake of cellular debris, patrolling monocytes engulf apoptotic cells and can then cross present antigen from the engulfed cell to T cells in the spleen. Interestingly, these antigen presenting Ly6C− monocytes express high levels of PDL1 following apoptotic cell engulfment and suppress endogenous antigen-specific T cell responses 52. Thus Ly6C− monocytes may contribute to self-antigen tolerance. Studies in human monocytes show that CD16+ nonclassical monocytes express ILT4, a receptor that binds HLA-G. The ILT4/HLA-G interaction is associated with fetal tolerance during pregnancy 53. Taken together these studies in mouse and man suggest that patrolling monocytes function in some capacity in antigen presentation to T cells, and may aid in eliciting a tolerogenic response.

Comparisons of human and mouse patrolling monocytes

Much of our knowledge about the functions of human non-classical monocytes is derived from comparative transcriptomic analyses. A number of studies have compared gene and protein expression between monocyte subsets in humans and mouse 10, 50, 54, 55. These expression studies identify a number of unique genes and activities in the patrolling monocyte population (See table 1). Two independent studies have provided transcriptional array data of all three human monocyte subsets and show that the ‘intermediate’ (CD14+CD16+) monocytes share a transcriptional repertoire that is in between that of both the nonclassical (CD14dimCD16+) and classical (CD14+CD16−) subsets 10, 56. While there is disagreement as to which subset the intermediate monocyte is more closely related, this might simply reflect differences in placement of the gating used to sort this population by flow cytometry. Nevertheless, the intermediate monocyte population only represents a minor frequency (5–10%) of the total nonclassical subset 50, thus the inclusion of this population should have little confounding influence on the interpretation of data comparing the mouse and human classical and non-classical subsets.

Table 1.

Genes up-regulated in nonclassical monocytes in both humans and mice grouped by function

| Cellular function | Gene Name | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Lineage-Determining Receptor | CSFR1 | 50 |

| Survival/Differentiation | Nur77 (NR4A1), BCL2A1A, DUSP5, HES1, OCT2 (POU2F2), TCF7L2 | 29, 50, 58 |

| Adhesion and Patrolling | CX3CR1, CD43 (SPN), CD11a (ITGAL/LFA-1), CD11c (ITGAX), CD31 (PECAM1), RRAS | 16, 50 |

| Immune Regulation | CD16 (Fcgr3), TNF, IL10R, IL1B*, IL6*, IL1RA*, TGFBR3, LAIR1, LTB, KLRD1, GZMA | 50, 10, 16, 58 |

| Viral Immunity | TLR7, IFITM1, IFITM2, IFITM3 | 10, 54, 58 |

In response to TLR7 stimulation

Ingersoll et al published a detailed comparative analysis between the human classical CD14+CD16− and nonclassical CD14−CD16+ subsets, and the mouse Ly6C+ and Ly6C− populations 50. This analysis demonstrated statistically significant similarities in the global gene expression profiles of the mouse and human classical and non-classical subsets alike 50. Cros et al independently confirmed these findings and went on to show that human CD14dimCD16+ monocytes patrol the vasculature of lymphoid deficient RAG1−/−IL2RG−/−CX3CR1GFP mice 10. Genomic studies also verify that nonclassical human monocytes have increased metabolic activities and efficient cytoskeletal dynamics that are indicative of actively patrolling cells 54, 55. These data provide compelling evidence that the human CD14dimCD16+ population represent a functionally orthologous cell subset to the mouse Ly6C− patrolling monocyte.

Conserved up-regulated genes encode many of the proteins that impart the key mechanistic features of the nonclassical subset, these include the patrolling-associated integrins LFA-1 and MAC-1 (ITGAM/CD11b), the chemokine receptor CX3CR1 as well as the inflammatory cytokine TNF. In total 63 genes were more abundant in both human and mouse nonclassical monocytes relative to their classical counterparts 50. The roles of most of these genes in monocyte biology are yet to be determined, but future studies will likely provide significant new insight into the functions of these cells. Other functional similarities between the mouse and human non-classical monocytes include an attenuated response to stimulation with the TLR4 agonist LPS (due to relatively low LPS/TLR4 co-receptor CD14 expression), and a heightened response to the viral DNA sensor TLR7 (due to relatively high TLR7 expression)10, 16.

Although global similarities have been drawn between the human CD14dimCD16+ monocytes and Ly6C− monocytes there are notable differences. For example the transcription factor PPARγ and known target genes including CD36 and FABP4 are higher in murine Ly6C− monocytes, but not observed in human CD16+ monocytes. Importantly, mouse nonclassical monocytes also expressed higher levels of genes involved in apoptotic cell uptake including Tgm2, Treml4, CD36, and CD51 whereas these genes were more highly expressed by human CD14+ classical monocytes, suggesting potential differences in apoptotic cell recognition 50. MHCII expression is also low/absent on mouse Ly6C− patrolling monocytes, but high on human patrolling monocytes, which may suggest better presentation of certain antigens by the human subset 16, 50. In total Ingersoll et al. found 33 genes to be reciprocally regulated between the human and mouse subsets 50. Thus, some caution must be made in making direct comparisons in patrolling monocyte function between species.

A recent ChIP-Seq analysis of primary human classical and non-classical monocytes has provided mechanistic insight into transcriptional differences between these cell types 54. Transcription factor binding motifs for the CEBP and ETS factors are enriched in the enhancers of all monocytes. This results is expected as these motifs are bound by the myeloid pioneer transcription factors CEBP and PU.1 which collaborate to drive the myeloid gene expression program 57. Transcription factor binding sites for KLF, IRF and NR4A transcription factors were more abundant in the non-classical subset. Currently no obligatory roles for KLF or IRF transcription factors have been implicated in non-classical monocyte function or development although KLF2 is more abundant in CD16+ monocytes 58, however the nuclear receptor transcription factor NR4A1 is crucial for Ly6C− monocyte development 29. Studies of mouse monocyte enhancer activity will inform whether or not the same enrichment for IRF and KLF factors is conserved between species.

Roles in disease

The unique ability of nonclassical monocytes to actively patrol the vasculature and potential capacity to resolve inflammation make them attractive targets for disease therapy. Generally, nonclassical monocytes are thought to be involved in the resolution of inflammation and differentiate into resident macrophage populations that work to heal wounding and resolve inflammation17. Studies have suggested that patrolling monocytes can preferentially differentiate into CD11c+ resident lung macrophages, implying a specialized role for these effector cells in the lung 20, 42. There is also some evidence that patrolling monocytes can differentiate into resident or anti-inflammatory “M2-like” macrophages, but the evidence for this is far from definitive and may be specific for the tissue and/or stimulus. Others have found that recruitment of patrolling monocytes and subsequent monocyte-mediated inflammatory responses (including TNF and ROS production) in certain tissues may potentially aggravate autoimmune diseases such as lupus nephritis and arthritis induced joint inflammation. These findings are summarized below and in Table 2.

Table 2.

Observed activities of nonclassical monocytes in disease.

| Disease | Observed Activity | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Atherosclerosis | CCR5 mediated recruitment to atherosclerotic plaques and reduced accumulation with statin treatment | 19, 59 |

| Number of circulating cells positively correlated with atherosclerotic lesion size | 5 | |

| Regulated survival and recruitment to atherosclerotic plaques by CX3CR1 | 17, 42 | |

| Nur77 hematopoietic knockout mice with absence of patrolling monocytes develop increased atherosclerosis and inflammatory macrophage content | 30 | |

| Remove lipids including oxLDL from circulation, and increased numbers in circulation in response to oxLDL treatment | 60 | |

| Preferential uptake of oxLDL by CD16+ monocytes in hypercholesterolemic patients | 61 | |

| Inversely correlated with high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol levels and associated with increased APOE4 expression in hypercholesterolemic patients | 72 | |

| Percentage of cells in circualtion correlated with small HDL levels | 73 | |

| Circulating CD16+ monocyte levels positively correlated with vulnerable plaques in coronary heart disease patients | 68, 69, 70 | |

| Myocardial infarction (MI) and Vascular Wounding | Recruitment during the reparative phase of MI | 74, 77 |

| Higher numbers in circulation of MI patients that did not develop ventricular thrombus formations | 78 | |

| Nur77 hematopoetic knockout mice have adverse cardiac remodeling post MI | 79 | |

| Recuitment associated with the recovery of vascular flow and a regenerative phenotype in a hind-limb ischemia model | 75 | |

| S1PR3 mediated recruitment and correlation with arteriogenesis in ischemic microvessels | 36 | |

| Redundant role in progression and recovery of ischemic stroke | 81 | |

| Neurological Disease and Damage | Attracted to and actively remove amyloid beta peptides from brain vasculature | 82 |

| Differentiate into perivascular macrophages and important role in maintaining blood brain barrier | 18 | |

| Prevent excito-toxicity and neuronal cell death | 83 | |

| Beneficial recruitment to the injured spinal cord | 84 | |

| Lupus and Kidney Disease | Accumulation of nonclassical monocytes to glomerular vessels | 10, 87 |

| Accumulation Associated with elevated levels of CX3CL1, proliferative glomerular lupus nephritis lesions, and disease activity | 87 | |

| Accumulate, recruit neutrophils, and remove damaged endothelial cell in the kidney vasculature in response to a TLR7-induced “danger signal” | 16 | |

| Arthritis | Critical for the initiation and progression of sterile joint inflammation, but derived macrophages may also be important for arthritic resolution | 92 |

| Increased circulating levels in rheumatoid arthritis patients associated with elevated levels of C-reactive protein, rheumatoid factor and more active disease | 93, 94 |

Atherosclerosis

Currently, little is known about the importance of nonclassical monocytes and their role in atherosclerotic development. Tracking studies have demonstrated that both classical and nonclassical subsets can enter atherosclerotic plaques in mice 19. Atherosclerotic lesion size has been shown to positively correlate with the number of both Ly6C− and Ly6C+ circulating monocyte subsets 5. Quantitative intravital imaging has also demonstrated a substantial accumulation of nonclassical mouse monocytes in lesions that can be reduced with statin treatment 59. In blood draws from APOE deficient mice on high fat diet there is an increase in the percentage of classical monocytes and decrease in the nonclassical population19. However, low numbers of patrolling monocytes analyzed in blood draws could be due to increased adherence and patrolling of nonclassical monocytes in the vasculature, and not due to a true reduction in cell number, though this has yet to be properly examined.

Experiments suggest that the Ly6C+ and Ly6C− monocyte subsets use different chemokines for recruitment to atherosclerotic lesions 19. Ly6C− monocyte recruitment to sites of atherosclerosis was reduced ~40% with CCR5 blockade, whereas Ly6C+ monocyte recruitment was reduced ~50% with either CCR5, CCR2, or CX3CR1 blockade 19. These findings suggest that CCR5 expression is at least partially responsible for nonclassical monocyte recruitment, but there are likely other recruitment factors yet to be identified.

Nonclassical monocytes actively patrol the vasculature and have been shown to phagocytize microparticles and mediate the removal of damaged endothelial cells in the vasculature 10, 16. Nonclassical Ly6C− monocytes can preferentially scavenge and accumulate lipids including oxLDL from the vasculature, and increase in numbers in response to oxLDL treatment 60. Likewise in patients with familial hypercholesteremia, CD16+ monocytes preferentially uptake oxLDL 61. Therefore it is easy to speculate that nonclassical monocytes may work to repair the vasculature or remove lipids from circulation under damaging inflammatory atherosclerotic conditions.

It has also been suggested that nonclassical monocytes may differentiate into resident anti-inflammatory “M2-like” macrophage populations that could suppress inflammatory conditions in atherosclerotic plaques 49, 62. However, a recent study suggests that while monocyte recruitment is important for early plaque development, it is local macrophage proliferation and not continual monocyte recruitment that dominate atherosclerotic plaque growth 63. This provocative possibility, in its early stage of investigation, merits closer study.

Work in our laboratory has identified that in the absence of Nur77 and patrolling monocytes, the remaining macrophage populations are polarized to a more inflammatory phenotype leading to increased atherosclerotic development 30. Macrophages from Nur77−/− mice express relatively high levels of tumor necrosis factor-α (TNFα) and nitric oxide, and low expression of Arginase-I upon inflammatory stimuli. Three independent studies have confirmed a direct role of Nur77 in resolving myeloid cell-mediated inflammation and suppressing atherosclerotic development 30, 64, 65. A conflicting study found no role of Nur77 in atherosclerotic development and may represent an outlier in the literature 66. In the majority of studies linking Nur77 deficiency to atherosclerotic development, Nur77 deficient macrophages are polarized toward a pro-inflammatory phenotype, exhibiting increased IL-12 and nitric oxide synthesis in response to activation by toll-like receptor (TLR) agonists. This increase in macrophage activation is driven by enhanced NF-κB activity and TLR expression in the absence of Nur77 30, 67. These results suggest that Nur77-dependent monocytes may be atheroprotective, and that the nonclassical monocytes themselves, or their derived effector cells, may suppress inflammatory macrophage activity. We are currently investigating if these differences in macrophage activity are related to the absence of a patrolling monocyte derived anti-inflammatory macrophage subset or if these effects are related to intrinsic Nur77 activity in macrophages.

In humans, increased numbers of circulating CD16+ monocytes are associated with increased coronary heart disease 68. CD16+ monocyte levels are also positively correlated with vulnerable plaques in coronary heart disease patients, and levels of CD16+ monocytes are significantly decreased in patients receiving statin treatment 69, 70. Unfortunately, these human studies did not distinguish between CD16+CD14dim nonclassical and CD16+CD14+ generally more inflammatory intermediate monocyte populations. A recent study of over 900 patients has suggested that it is mainly the CD16+CD14+ intermediate monocytes that are positive predictors for cardiovascular events, while the CD16+CD14dim nonclassical monocyte subset showed no correlation71.

In hypercholesterolemic patients, the number of nonclassical monocytes is inversely correlated with high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol levels and is associated with increased APOE4 expression, a factor related to higher plasma cholesterol 72. Percentage of nonclassical monocytes is also positively associated with small HDL levels 73. Nevertheless, the association between nonclassical monocytes and atherosclerosis does not necessarily imply causality. Research into the functional relationships between patrolling monocytes, production of inflammatory or anti-inflammatory factors, and ability to remove lipids or repair the vasculature in cardiovascular disease is needed to establish positive effector cell associations.

Myocardial infarction and wounding

With respect to myocardial infarction (MI) and wound healing, patrolling monocytes have been associated with reparative and proangiogenic effects 74–76. In mouse models of MI the depletion of monocytes leads to higher mortality and reduced ventricular function suggesting that monocytes facilitate wound healing and cardiac remodeling 8. Classical monocytes migrate into infarcted heart tissue during the early inflammatory phase of injury, and nonclassical monocytes are sequentially recruited at day 5 during the reparative phase 74. Similar findings were observed in patients where nonclassical monocytes peaked at 5 days post MI in the reparative phase, suggesting a possible reparative role of nonclassical monocytes 77. MI patients that did not develop ventricular thrombus formations had higher circulating nonclassical monocytes further suggesting a protective function of the subset 78. Mice in which bone marrow derived cells lack Nur77 expression serve as a model for the absence of patrolling monocytes. These mice display adverse cardiac remodeling post MI, again highlighting a role for patrolling monocyte in post MI wound healing 79. However, other anti-inflammatory effects of Nur77 on classical monocyte derived macrophages may also affect the MI outcome in this model. Further research is needed to examine the mechanisms by which patrolling monocytes may respond and repair damaged cardiac tissue. For example, it will be interesting to learn whether patrolling monocytes contribute to the local cardiac macrophage pool or if they function as terminally differentiated cells within the myocardium.

In a hind-limb ischemia model, proangiogenic nonclassical monocytes were associated with recovery of vascular flow and a more regenerative phenotype 75. Similarly, S1PR3 recruited nonclassical monocytes were correlated with arteriogenesis in ischemic microvessels 36. With laser-induced focal tissue damage of the ear dermis in mice, CX3CR1high nonclassical monocytes quickly align along collagen fibers at the outer edges of the wounding, in a prime location for repairing tissue 80. However, another study concluded that in a cerebral hypoxia-ischemia model patrolling monocytes were redundant in the progression and recovery of ischemic stroke 81. Additional research is needed to determine if these conflicting findings can be attributed to patrolling monocyte function in specific tissues or general differences in ischemic models. Combined these data generally demonstrate a beneficial effect of nonclassical monocytes in vascular repair and restoring organ function.

Neurological diseases and damage

Nonclassical Ly6C− monocytes patrol the brain and nervous system vasculature and have been associated with a variety of generally protective activities 18, 82. Nonclassical patrolling monocytes are attracted to amyloid beta peptides and have been observed actively removing amyloid beta from the brain vasculature 82. This suggests that patrolling monocytes may be potential therapeutic targets for reducing amyloid beta deposits associated with Alzheimer’s disease. Live imaging of the brain has also revealed Ly6C− CX3CR1high monocyte differentiation into perivascular macrophages, a cell that is important for maintaining the blood-brain barrier and preventing damaging inflammatory cell influx into nervous tissue 18. Nonclassical monocytes were attracted during endotoxemia by TNFα, IL1β and angiopoietin-2.

Other possible roles of patrolling monocytes in the nervous system include preventing excito-toxicity and beneficial recruitment to the injured spinal cord. Absence of patrolling monocytes using hematopoietic deletions of Nur77 or CX3CR1 exacerbated excito-toxicicity and neuronal cell death 83. Another study demonstrated that Ly6C− CX3CR1high monocytes are actively recruited via the choroid plexus to help recovery of spinal cord injuries. 84. Taken together, these finding reveal multiple protective roles of patrolling monocytes in the vasculature of the brain and nervous system.

Lupus and kidney disease

Glomerulonephritis is the leading cause of kidney failure and death in Lupus patients. Kidney glomerulus inflammation results from an increased duration and retention of migratory leukocytes and patrolling monocytes in a CD11b dependent manner 16, 85, 86. Accumulation of nonclassical monocytes to glomerular vessels in the kidneys of Lupus patients has been documented 10, 87. Recruitment to the kidney vasculature is at least partially mediated by CX3CL1 (fractalkine) expression in the damaged kidney. Elevated levels of CX3CL1 in the glomerular vessels of lupus patients is associated with recruitment of CD16+ monocytes, proliferative glomerular lupus nephritis lesions, and disease activity 87. Interestingly, glucocorticoid therapy had a tendency to decrease both glomerular fractalkine expression and CD16+ monocyte numbers. Nonclassical human monocytes can preferentially make TNF and CCL3 in response to serum from Lupus patients, suggesting an inflammatory and active state of these cells under Lupus-like conditions 10. The pattern recognition receptor TLR7 plays important roles in autoimmune responses directed against DNA- and RNA-containing nuclear antigens and the pathogenesis of Lupus in susceptible hosts 88–91. TLR7 agonists can specifically induce nonclassical monocytes to produce proinflammatory cytokine including TNF, CCL3, IL6, IL1beta, and CXCL1 16. In response to TLR7-induced “danger signals” patrolling monocytes accumulate in the kidney microvasculature which recruit neutrophils and work to remove damaged endothelial cells 16. These findings suggest that though patrolling monocytes may initially be recruited to protect the kidney vascular endothelium, they could also contribute to tissue damage in susceptible individuals.

Arthritis

Nonclassical monocytes have also been associated with both the initiation and resolution of autoimmune joint inflammation 92. An elegant study by Misharin et al. demonstrated that Ly6C− monocytes are actively recruited to injured joints from the vasculature, can differentiate to inflammatory macrophages in the joint, and are critical for the initiation and progression of sterile joint inflammation in mouse models 92. However, with the development of arthritis Ly6C− monocyte-derived macrophages shift to an alternatively activated phenotype, which promote the resolution of joint inflammation.

In humans nonclassical monocyte recruitment is likewise associated with rheumatoid arthritis. Nonclassical monocytes in blood were significantly increased in patients with rheumatoid arthritis compared to healthy controls 93, 94. Patients with elevated nonclassical monocyte were associated with more active disease, and elevated levels of erythrocyte sedimentation rates, C-reactive protein and rheumatoid factor 94. Patients responding to therapy developed lower nonclassical monocyte frequencies, but nonresponders increased their frequency. Additionally, the expression of the chemokine receptors CCR5, CCR1 and ICAM-1 were higher on nonclassical monocytes from patient with active arthritis 94. These finding show that nonclassical monocytes infiltrate inflamed joints and may contribute to both the induction and resolution of joint inflammation.

Potential targeting and future research

Though many interesting functions have been associated with patrolling monocytes, the kinetics of their recruitment and capacity to differentiate into effector macrophage populations in inflammatory disease are still uncertain. Furthermore, the extent to which patrolling monocytes directly participate in the resolution of inflammation and the specific populations of macrophages/myeloid effector cells (if any) that derive from patrolling monocytes is currently unknown. Better in situ techniques and models to distinguish monocyte and derived macrophage populations in tissues are needed to verify the extent of which nonclassical patrolling monocytes contribution to the myeloid compartment in inflammatory disease. Other functional characteristics of both monocyte subsets including differences in their respective capacities to proliferate, particularly in response to insult, are still unknown, and critical to our understanding of these cells.

Specifically targeting nonclassical monocyte production and activities via Nur77 mediated regulation or liposomes may be of therapeutic benefit. Directed recruitment of nonclassical monocytes by S1P, TLR7 agonists, CX3CL1 or CCL5 may also be of interest to enhancing repair of damaged vascular or tissues. Interestingly, for possible targeting of aberrant nonclassical monocyte activities, it has been shown that glucocorticoid treatment can deplete non-classical monocyte populations within a few days of treatment, and may contribute to the mechanism of glucocorticoid mediated immune suppression 95, 96. Additional research is needed to delineate the inherent function of patrolling monocyte subsets in inflammatory diseases.

Significance.

Recent studies have identified at least two distinct monocyte sub-populations within the circulation—classical and nonoclassical patrolling monocytes. While many studies have examined the role of classical monocytes within the vasculature and in response to inflammatory diseases, comparatively few have assessed the unique activities of patrolling monocytes. Patrolling monocytes function to remove damaged cells and debris from the vasculature, and have been associated with wound healing and the resolution of inflammation in damaged tissues. This review summarizes the current knowledge and unique functions of nonclassical patrolling monocyte in the vasculature and during inflammatory disease.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Julie Larson for assistance with the artistic rendering of Figure 1.

Sources of funding: This work is supported by NIH R01 HL118765 (to C.C.H.), American Heart Association Postdoctoral Fellowship 13POST16990029 (to R.T.), American Heart Association Scientist Development Grant 125SDG12070005 (to R.N.H.), and LJI Board of Director’s Fellowship (to R.N.H.).

Footnotes

Disclosure: None.

References

- 1.Swirski FK. Monocyte recruitment and macrophage proliferation in atherosclerosis. Kardiol Pol. 2014;72:311–314. doi: 10.5603/KP.a2014.0021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Swirski FK, Nahrendorf M. Leukocyte behavior in atherosclerosis, myocardial infarction, and heart failure. Science. 2013;339:161–166. doi: 10.1126/science.1230719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Swirski FK, Libby P, Aikawa E, Alcaide P, Luscinskas FW, Weissleder R, Pittet MJ. Ly-6chi monocytes dominate hypercholesterolemia-associated monocytosis and give rise to macrophages in atheromata. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:195–205. doi: 10.1172/JCI29950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Smith JD, Trogan E, Ginsberg M, Grigaux C, Tian J, Miyata M. Decreased atherosclerosis in mice deficient in both macrophage colony-stimulating factor (op) and apolipoprotein e. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92:8264–8268. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.18.8264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Combadière C, Potteaux S, Rodero M, Simon T, Pezard A, Esposito B, Merval R, Proudfoot A, Tedgui A, Mallat Z. Combined inhibition of ccl2, cx3cr1, and ccr5 abrogates ly6c(hi) and ly6c(lo) monocytosis and almost abolishes atherosclerosis in hypercholesterolemic mice. Circulation. 2008;117:1649–1657. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.745091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lessner SM, Prado HL, Waller EK, Galis ZS. Atherosclerotic lesions grow through recruitment and proliferation of circulating monocytes in a murine model. Am J Pathol. 2002;160:2145–2155. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)61163-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boring L, Gosling J, Cleary M, Charo IF. Decreased lesion formation in ccr2−/− mice reveals a role for chemokines in the initiation of atherosclerosis. Nature. 1998;394:894–897. doi: 10.1038/29788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.van Amerongen MJ, Harmsen MC, van Rooijen N, Petersen AH, van Luyn MJ. Macrophage depletion impairs wound healing and increases left ventricular remodeling after myocardial injury in mice. Am J Pathol. 2007;170:818–829. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2007.060547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Geissmann F, Jung S, Littman D. Blood monocytes consist of two principal subsets with distinct migratory properties. Immunity. 2003;19:71–82. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(03)00174-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cros J, Cagnard N, Woollard K, Patey N, Zhang SY, Senechal B, Puel A, Biswas SK, Moshous D, Picard C, Jais JP, D’Cruz D, Casanova JL, Trouillet C, Geissmann F. Human cd14dim monocytes patrol and sense nucleic acids and viruses via tlr7 and tlr8 receptors. Immunity. 2010;33:375–386. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.08.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Randolph GJ. Emigration of monocyte-derived cells to lymph nodes during resolution of inflammation and its failure in atherosclerosis. Curr Opin Lipidol. 2008;19:462–468. doi: 10.1097/MOL.0b013e32830d5f09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tacke F, Ginhoux F, Jakubzick C, van Rooijen N, Merad M, Randolph G. Immature monocytes acquire antigens from other cells in the bone marrow and present them to t cells after maturing in the periphery. J Exp Med. 2006;203:583–597. doi: 10.1084/jem.20052119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ziegler-Heitbrock L, Ancuta P, Crowe S, Dalod M, Grau V, Hart DN, Leenen PJ, Liu YJ, MacPherson G, Randolph GJ, Scherberich J, Schmitz J, Shortman K, Sozzani S, Strobl H, Zembala M, Austyn JM, Lutz MB. Nomenclature of monocytes and dendritic cells in blood. Blood. 2010;116:e74–80. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-02-258558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Passlick B, Flieger D, Ziegler-Heitbrock HW. Identification and characterization of a novel monocyte subpopulation in human peripheral blood. Blood. 1989;74:2527–2534. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tacke F, Randolph GJ. Migratory fate and differentiation of blood monocyte subsets. Immunobiology. 2006;211:609–618. doi: 10.1016/j.imbio.2006.05.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Carlin LM, Stamatiades EG, Auffray C, Hanna RN, Glover L, Vizcay-Barrena G, Hedrick CC, Cook HT, Diebold S, Geissmann F. Nr4a1-dependent ly6c(low) monocytes monitor endothelial cells and orchestrate their disposal. Cell. 2013;153:362–375. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.03.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Auffray C, Fogg D, Garfa M, Elain G, Join-Lambert O, Kayal S, Sarnacki S, Cumano A, Lauvau G, Geissmann F. Monitoring of blood vessels and tissues by a population of monocytes with patrolling behavior. Science. 2007;317:666–670. doi: 10.1126/science.1142883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Audoy-Rémus J, Richard JF, Soulet D, Zhou H, Kubes P, Vallières L. Rod-shaped monocytes patrol the brain vasculature and give rise to perivascular macrophages under the influence of proinflammatory cytokines and angiopoietin-2. J Neurosci. 2008;28:10187–10199. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3510-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tacke F, Alvarez D, Kaplan T, Jakubzick C, Spanbroek R, Llodra J, Garin A, Liu J, Mack M, van Rooijen N, Lira S, Habenicht A, Randolph G. Monocyte subsets differentially employ ccr2, ccr5, and cx3cr1 to accumulate within atherosclerotic plaques. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:185–194. doi: 10.1172/JCI28549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Landsman L, Varol C, Jung S. Distinct differentiation potential of blood monocyte subsets in the lung. J Immunol. 2007;178:2000–2007. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.4.2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Varol C, Landsman L, Fogg DK, Greenshtein L, Gildor B, Margalit R, Kalchenko V, Geissmann F, Jung S. Monocytes give rise to mucosal, but not splenic, conventional dendritic cells. J Exp Med. 2007;204:171–180. doi: 10.1084/jem.20061011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.van Furth R, Cohn ZA. The origin and kinetics of mononuclear phagocytes. J Exp Med. 1968;128:415–435. doi: 10.1084/jem.128.3.415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yona S, Kim KW, Wolf Y, Mildner A, Varol D, Breker M, Strauss-Ayali D, Viukov S, Guilliams M, Misharin A, Hume DA, Perlman H, Malissen B, Zelzer E, Jung S. Fate mapping reveals origins and dynamics of monocytes and tissue macrophages under homeostasis. Immunity. 2013;38:79–91. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fogg D, Sibon C, Miled C, Jung S, Aucouturier P, Littman D, Cumano A, Geissmann F. A clonogenic bone marrow progenitor specific for macrophages and dendritic cells. Science. 2006;311:83–87. doi: 10.1126/science.1117729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hettinger J, Richards DM, Hansson J, Barra MM, Joschko AC, Krijgsveld J, Feuerer M. Origin of monocytes and macrophages in a committed progenitor. Nat Immunol. 2013;14:821–830. doi: 10.1038/ni.2638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Varol C, Yona S, Jung S. Origins and tissue-context-dependent fates of blood monocytes. Immunol Cell Biol. 2009;87:30–38. doi: 10.1038/icb.2008.90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Alder JK, Georgantas RW, Hildreth RL, Kaplan IM, Morisot S, Yu X, McDevitt M, Civin CI. Kruppel-like factor 4 is essential for inflammatory monocyte differentiation in vivo. J Immunol. 2008;180:5645–5652. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.8.5645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kurotaki D, Osato N, Nishiyama A, Yamamoto M, Ban T, Sato H, Nakabayashi J, Umehara M, Miyake N, Matsumoto N, Nakazawa M, Ozato K, Tamura T. Essential role of the irf8-klf4 transcription factor cascade in murine monocyte differentiation. Blood. 2013;121:1839–1849. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-06-437863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hanna RN, Carlin LM, Hubbeling HG, Nackiewicz D, Green AM, Punt JA, Geissmann F, Hedrick CC. The transcription factor nr4a1 (nur77) controls bone marrow differentiation and the survival of ly6c-monocytes. Nat Immunol. 2011;12:778–785. doi: 10.1038/ni.2063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hanna RN, Shaked I, Hubbeling HG, Punt JA, Wu R, Herrley E, Zaugg C, Pei H, Geissmann F, Ley K, Hedrick CC. Nr4a1 (nur77) deletion polarizes macrophages toward an inflammatory phenotype and increases atherosclerosis. Circ Res. 2012;110:416–427. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.111.253377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Serbina NV, Jia T, Hohl TM, Pamer EG. Monocyte-mediated defense against microbial pathogens. Annu Rev Immunol. 2008;26:421–452. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.26.021607.090326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tsou CL, Peters W, Si Y, Slaymaker S, Aslanian AM, Weisberg SP, Mack M, Charo IF. Critical roles for ccr2 and mcp-3 in monocyte mobilization from bone marrow and recruitment to inflammatory sites. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:902–909. doi: 10.1172/JCI29919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Weber C, Belge KU, von Hundelshausen P, Draude G, Steppich B, Mack M, Frankenberger M, Weber KS, Ziegler-Heitbrock HW. Differential chemokine receptor expression and function in human monocyte subpopulations. J Leukoc Biol. 2000;67:699–704. doi: 10.1002/jlb.67.5.699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lewis ND, Haxhinasto SA, Anderson SM, Stefanopoulos DE, Fogal SE, Adusumalli P, Desai SN, Patnaude LA, Lukas SM, Ryan KR, Slavin AJ, Brown ML, Modis LK. Circulating monocytes are reduced by sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor modulators independently of s1p3. J Immunol. 2013;190:3533–3540. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1201810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cyster JG. Chemokines, sphingosine-1-phosphate, and cell migration in secondary lymphoid organs. Annu Rev Immunol. 2005;23:127–159. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.23.021704.115628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Awojoodu AO, Ogle ME, Sefcik LS, Bowers DT, Martin K, Brayman KL, Lynch KR, Peirce-Cottler SM, Botchwey E. Sphingosine 1-phosphate receptor 3 regulates recruitment of anti-inflammatory monocytes to microvessels during implant arteriogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:13785–13790. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1221309110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Debien E, Mayol K, Biajoux V, Daussy C, De Aguero MG, Taillardet M, Dagany N, Brinza L, Henry T, Dubois B, Kaiserlian D, Marvel J, Balabanian K, Walzer T. S1pr5 is pivotal for the homeostasis of patrolling monocytes. Eur J Immunol. 2013;43:1667–1675. doi: 10.1002/eji.201343312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kuwano Y, Spelten O, Zhang H, Ley K, Zarbock A. Rolling one- or p-selectin induces the extended but not high-affinity conformation of lfa-1 in neutrophils. Blood. 2010;116:617–624. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-01-266122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hentzen ER, Neelamegham S, Kansas GS, Benanti JA, McIntire LV, Smith CW, Simon SI. Sequential binding of cd11a/cd18 and cd11b/cd18 defines neutrophil capture and stable adhesion to intercellular adhesion molecule-1. Blood. 2000;95:911–920. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Moser M, Legate KR, Zent R, Fässler R. The tail of integrins, talin, and kindlins. Science. 2009;324:895–899. doi: 10.1126/science.1163865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Auffray C, Fogg D, Narni-Mancinelli E, et al. Cx3cr1+ cd115+ cd135+ common macrophage/dc precursors and the role of cx3cr1 in their response to inflammation. J Exp Med. 2009;206:595–606. doi: 10.1084/jem.20081385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jakubzick C, Tacke F, Ginhoux F, Wagers AJ, van Rooijen N, Mack M, Merad M, Randolph GJ. Blood monocyte subsets differentially give rise to cd103+ and cd103− pulmonary dendritic cell populations. J Immunol. 2008;180:3019–3027. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.5.3019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ge S, Hertel B, Susnik N, Rong S, Dittrich AM, Schmitt R, Haller H, von Vietinghoff S. Interleukin 17 receptor a modulates monocyte subsets and macrophage generation in vivo. PLoS One. 2014;9:e85461. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0085461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bhattacharya S, Ray RM, Johnson LR. Stat3-mediated transcription of bcl-2, mcl-1 and c-iap2 prevents apoptosis in polyamine-depleted cells. Biochem J. 2005;392:335–344. doi: 10.1042/BJ20050465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Heimbeck I, Hofer TP, Eder C, Wright AK, Frankenberger M, Marei A, Boghdadi G, Scherberich J, Ziegler-Heitbrock L. Standardized single-platform assay for human monocyte subpopulations: Lower cd14+cd16++ monocytes in females. Cytometry A. 2010;77:823–830. doi: 10.1002/cyto.a.20942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Steppich B, Dayyani F, Gruber R, Lorenz R, Mack M, Ziegler-Heitbrock HW. Selective mobilization of cd14(+)cd16(+) monocytes by exercise. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2000;279:C578–586. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.2000.279.3.C578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Dimitrov S, Lange T, Born J. Selective mobilization of cytotoxic leukocytes by epinephrine. J Immunol. 2010;184:503–511. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0902189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Heidt T, Sager HB, Courties G, Dutta P, Iwamoto Y, Zaltsman A, von Zur Muhlen C, Bode C, Fricchione GL, Denninger J, Lin CP, Vinegoni C, Libby P, Swirski FK, Weissleder R, Nahrendorf M. Chronic variable stress activates hematopoietic stem cells. Nat Med. 2014;20:754–758. doi: 10.1038/nm.3589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Woollard KJ, Geissmann F. Monocytes in atherosclerosis: Subsets and functions. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2010;7:77–86. doi: 10.1038/nrcardio.2009.228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ingersoll MA, Spanbroek R, Lottaz C, Gautier EL, Frankenberger M, Hoffmann R, Lang R, Haniffa M, Collin M, Tacke F, Habenicht AJ, Ziegler-Heitbrock L, Randolph GJ. Comparison of gene expression profiles between human and mouse monocyte subsets. Blood. 2010;115:e10–19. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-07-235028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Szaflarska A, Baj-Krzyworzeka M, Siedlar M, Weglarczyk K, Ruggiero I, Hajto B, Zembala M. Antitumor response of cd14+/cd16+ monocyte subpopulation. Exp Hematol. 2004;32:748–755. doi: 10.1016/j.exphem.2004.05.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Peng Y, Latchman Y, Elkon KB. Ly6c(low) monocytes differentiate into dendritic cells and cross-tolerize t cells through pdl-1. J Immunol. 2009;182:2777–2785. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0803172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Allan DS, Colonna M, Lanier LL, Churakova TD, Abrams JS, Ellis SA, McMichael AJ, Braud VM. Tetrameric complexes of human histocompatibility leukocyte antigen (hla)-g bind to peripheral blood myelomonocytic cells. J Exp Med. 1999;189:1149–1156. doi: 10.1084/jem.189.7.1149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Schmidl C, Renner K, Peter K, et al. Transcription and enhancer profiling in human monocyte subsets. Blood. 2014;123:e90–99. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-02-484188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Anbazhagan K, Duroux-Richard I, Jorgensen C, Apparailly F. Transcriptomic network support distinct roles of classical and non-classical monocytes in human. Int Rev Immunol. 2014;33:470–489. doi: 10.3109/08830185.2014.902453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wong KL, Tai JJ, Wong WC, Han H, Sem X, Yeap WH, Kourilsky P, Wong SC. Gene expression profiling reveals the defining features of the classical, intermediate, and nonclassical human monocyte subsets. Blood. 2011;118:e16–31. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-12-326355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Heinz S, Benner C, Spann N, Bertolino E, Lin YC, Laslo P, Cheng JX, Murre C, Singh H, Glass CK. Simple combinations of lineage-determining transcription factors prime cis-regulatory elements required for macrophage and b cell identities. Mol Cell. 2010;38:576–589. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ancuta P, Liu KY, Misra V, Wacleche VS, Gosselin A, Zhou X, Gabuzda D. Transcriptional profiling reveals developmental relationship and distinct biological functions of cd16+ and cd16− monocyte subsets. BMC Genomics. 2009;10:403. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-10-403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Haka AS, Potteaux S, Fraser H, Randolph GJ, Maxfield FR. Quantitative analysis of monocyte subpopulations in murine atherosclerotic plaques by multiphoton microscopy. PLoS One. 2012;7:e44823. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0044823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wu H, Gower RM, Wang H, Perrard XY, Ma R, Bullard DC, Burns AR, Paul A, Smith CW, Simon SI, Ballantyne CM. Functional role of cd11c+ monocytes in atherogenesis associated with hypercholesterolemia. Circulation. 2009;119:2708–2717. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.823740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Mosig S, Rennert K, Krause S, Kzhyshkowska J, Neunübel K, Heller R, Funke H. Different functions of monocyte subsets in familial hypercholesterolemia: Potential function of cd14+ cd16+ monocytes in detoxification of oxidized ldl. FASEB J. 2009;23:866–874. doi: 10.1096/fj.08-118240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ley K, Miller YI, Hedrick CC. Monocyte and macrophage dynamics during atherogenesis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2011;31:1506–1516. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.110.221127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Robbins CS, Hilgendorf I, Weber GF, et al. Local proliferation dominates lesional macrophage accumulation in atherosclerosis. Nat Med. 2013;19:1166–1172. doi: 10.1038/nm.3258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Hamers AA, Vos M, Rassam F, Marinković G, Marincovic G, Kurakula K, van Gorp PJ, de Winther MP, Gijbels MJ, de Waard V, de Vries CJ. Bone marrow-specific deficiency of nuclear receptor nur77 enhances atherosclerosis. Circ Res. 2012;110:428–438. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.111.260760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Hu YW, Zhang P, Yang JY, Huang JL, Ma X, Li SF, Zhao JY, Hu YR, Wang YC, Gao JJ, Sha YH, Zheng L, Wang Q. Nur77 decreases atherosclerosis progression in apoe(−/−) mice fed a high-fat/high-cholesterol diet. PLoS One. 2014;9:e87313. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0087313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Chao LC, Soto E, Hong C, Ito A, Pei L, Chawla A, Conneely OM, Tangirala RK, Evans RM, Tontonoz P. Bone marrow nr4a expression is not a dominant factor in the development of atherosclerosis or macrophage polarization in mice. J Lipid Res. 2013;54:806–815. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M034157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Saijo K, Winner B, Carson CT, Collier JG, Boyer L, Rosenfeld MG, Gage FH, Glass CK. A nurr1/corest pathway in microglia and astrocytes protects dopaminergic neurons from inflammation-induced death. Cell. 2009;137:47–59. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.01.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Huang Y, Yin H, Wang J, Ma X, Zhang Y, Chen K. The significant increase of fcγriiia (cd16), a sensitive marker, in patients with coronary heart disease. Gene. 2012;504:284–287. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2012.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kashiwagi M, Imanishi T, Tsujioka H, Ikejima H, Kuroi A, Ozaki Y, Ishibashi K, Komukai K, Tanimoto T, Ino Y, Kitabata H, Hirata K, Akasaka T. Association of monocyte subsets with vulnerability characteristics of coronary plaques as assessed by 64-slice multidetector computed tomography in patients with stable angina pectoris. Atherosclerosis. 2010;212:171–176. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2010.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Imanishi T, Ikejima H, Tsujioka H, Kuroi A, Ishibashi K, Komukai K, Tanimoto T, Ino Y, Takeshita T, Akasaka T. Association of monocyte subset counts with coronary fibrous cap thickness in patients with unstable angina pectoris. Atherosclerosis. 2010;212:628–635. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2010.06.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Rogacev KS, Cremers B, Zawada AM, Seiler S, Binder N, Ege P, Große-Dunker G, Heisel I, Hornof F, Jeken J, Rebling NM, Ulrich C, Scheller B, Böhm M, Fliser D, Heine GH. Cd14++cd16+ monocytes independently predict cardiovascular events: A cohort study of 951 patients referred for elective coronary angiography. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;60:1512–1520. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2012.07.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Rothe G, Gabriel H, Kovacs E, Klucken J, Stöhr J, Kindermann W, Schmitz G. Peripheral blood mononuclear phagocyte subpopulations as cellular markers in hypercholesterolemia. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1996;16:1437–1447. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.16.12.1437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Krychtiuk KA, Kastl SP, Pfaffenberger S, Pongratz T, Hofbauer SL, Wonnerth A, Katsaros KM, Goliasch G, Gaspar L, Huber K, Maurer G, Dostal E, Oravec S, Wojta J, Speidl WS. Small high-density lipoprotein is associated with monocyte subsets in stable coronary artery disease. Atherosclerosis. 2014;237:589–596. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2014.10.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Nahrendorf M, Swirski FK, Aikawa E, Stangenberg L, Wurdinger T, Figueiredo JL, Libby P, Weissleder R, Pittet MJ. The healing myocardium sequentially mobilizes two monocyte subsets with divergent and complementary functions. J Exp Med. 2007;204:3037–3047. doi: 10.1084/jem.20070885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Ryu JC, Davidson BP, Xie A, Qi Y, Zha D, Belcik JT, Caplan ES, Woda JM, Hedrick CC, Hanna RN, Lehman N, Zhao Y, Ting A, Lindner JR. Molecular imaging of the paracrine proangiogenic effects of progenitor cell therapy in limb ischemia. Circulation. 2013;127:710–719. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.116103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Milch HS, Schubert SY, Hammond S, Spiegel JH. Enhancement of ischemic wound healing by inducement of local angiogenesis. Laryngoscope. 2010;120:1744–1748. doi: 10.1002/lary.21068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Tsujioka H, Imanishi T, Ikejima H, et al. Impact of heterogeneity of human peripheral blood monocyte subsets on myocardial salvage in patients with primary acute myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;54:130–138. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.04.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Frantz S, Hofmann U, Fraccarollo D, et al. Monocytes/macrophages prevent healing defects and left ventricular thrombus formation after myocardial infarction. FASEB J. 2013;27:871–881. doi: 10.1096/fj.12-214049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Hilgendorf I, Gerhardt L, Tan TC, Winter C, Holderried TA, Chousterman BG, Iwamoto Y, Liao R, Zirlik A, Scherrer-Crosbie M, Hedrick CC, Libby P, Nahrendorf M, Weissleder R, Swirski FK. Ly-6Chigh monocytes depend on nr4a1 to balance both inflammatory and reparative phases in the infarcted myocardium. Circ Res. 2014;183:6733–43. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.114.303204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Lämmermann T, Afonso PV, Angermann BR, Wang JM, Kastenmüller W, Parent CA, Germain RN. Neutrophil swarms require ltb4 and integrins at sites of cell death in vivo. Nature. 2013;498:371–375. doi: 10.1038/nature12175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Michaud JP, Pimentel-Coelho PM, Tremblay Y, Rivest S. The impact of ly6clow monocytes after cerebral hypoxia-ischemia in adult mice. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2014;34:e1–9. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2014.80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Michaud JP, Bellavance MA, Préfontaine P, Rivest S. Real-time in vivo imaging reveals the ability of monocytes to clear vascular amyloid beta. Cell Rep. 2013;5:646–653. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2013.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Bellavance MA, Gosselin D, Yong VW, Stys PK, Rivest S. Patrolling monocytes play a critical role in cx3cr1-mediated neuroprotection during excitotoxicity. Brain Struct Funct. 2014 doi: 10.1007/s00429-014-0759-z. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Shechter R, Miller O, Yovel G, Rosenzweig N, London A, Ruckh J, Kim KW, Klein E, Kalchenko V, Bendel P, Lira SA, Jung S, Schwartz M. Recruitment of beneficial m2 macrophages to injured spinal cord is orchestrated by remote brain choroid plexus. Immunity. 2013;38:555–569. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.02.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Devi S, Li A, Westhorpe CL, Lo CY, Abeynaike LD, Snelgrove SL, Hall P, Ooi JD, Sobey CG, Kitching AR, Hickey MJ. Multiphoton imaging reveals a new leukocyte recruitment paradigm in the glomerulus. Nat Med. 2013;19:107–112. doi: 10.1038/nm.3024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Lin SL, Castaño AP, Nowlin BT, Lupher ML, Duffield JS. Bone marrow ly6chigh monocytes are selectively recruited to injured kidney and differentiate into functionally distinct populations. J Immunol. 2009;183:6733–6743. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0901473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Yoshimoto S, Nakatani K, Iwano M, Asai O, Samejima K, Sakan H, Terada M, Harada K, Akai Y, Shiiki H, Nose M, Saito Y. Elevated levels of fractalkine expression and accumulation of cd16+ monocytes in glomeruli of active lupus nephritis. Am J Kidney Dis. 2007;50:47–58. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2007.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Barrat FJ, Meeker T, Chan JH, Guiducci C, Coffman RL. Treatment of lupus-prone mice with a dual inhibitor of tlr7 and tlr9 leads to reduction of autoantibody production and amelioration of disease symptoms. Eur J Immunol. 2007;37:3582–3586. doi: 10.1002/eji.200737815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Deane JA, Pisitkun P, Barrett RS, Feigenbaum L, Town T, Ward JM, Flavell RA, Bolland S. Control of toll-like receptor 7 expression is essential to restrict autoimmunity and dendritic cell proliferation. Immunity. 2007;27:801–810. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.09.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Vollmer J, Tluk S, Schmitz C, Hamm S, Jurk M, Forsbach A, Akira S, Kelly KM, Reeves WH, Bauer S, Krieg AM. Immune stimulation mediated by autoantigen binding sites within small nuclear rnas involves toll-like receptors 7 and 8. J Exp Med. 2005;202:1575–1585. doi: 10.1084/jem.20051696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Santiago-Raber ML, Dunand-Sauthier I, Wu T, Li QZ, Uematsu S, Akira S, Reith W, Mohan C, Kotzin BL, Izui S. Critical role of tlr7 in the acceleration of systemic lupus erythematosus in tlr9-deficient mice. J Autoimmun. 2010;34:339–348. doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2009.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Misharin AV, Cuda CM, Saber R, Turner JD, Gierut AK, Haines GK, Berdnikovs S, Filer A, Clark AR, Buckley CD, Mutlu GM, Budinger GR, Perlman H. Nonclassical ly6c(−) monocytes drive the development of inflammatory arthritis in mice. Cell Rep. 2014;9:591–604. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2014.09.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Cairns AP, Crockard AD, Bell AL. The cd14+ cd16+ monocyte subset in rheumatoid arthritis and systemic lupus erythematosus. Rheumatol Int. 2002;21:189–192. doi: 10.1007/s00296-001-0165-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Kawanaka N, Yamamura M, Aita T, Morita Y, Okamoto A, Kawashima M, Iwahashi M, Ueno A, Ohmoto Y, Makino H. Cd14+, cd16+ blood monocytes and joint inflammation in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2002;46:2578–2586. doi: 10.1002/art.10545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Fingerle-Rowson G, Angstwurm M, Andreesen R, Ziegler-Heitbrock HW. Selective depletion of cd14+ cd16+ monocytes by glucocorticoid therapy. Clin Exp Immunol. 1998;112:501–506. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.1998.00617.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Dayyani F, Belge KU, Frankenberger M, Mack M, Berki T, Ziegler-Heitbrock L. Mechanism of glucocorticoid-induced depletion of human cd14+cd16+ monocytes. J Leukoc Biol. 2003;74:33–39. doi: 10.1189/jlb.1202612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]