Abstract

Allergic asthma is a chronic inflammatory disease of the airways characterized by excessive eosinophilic and lymphocytic inflammation with associated changes in the extracellular matrix (ECM) resulting in airway wall remodeling. Hyaluronan (HA) is a nonsulfated glycosaminoglycan ECM component that functions as a structural cushion in its high molecular mass (HMM) but has been implicated in metastasis and other disease processes when it is degraded to smaller fragments. However, relatively little is known about the role HA in mediating inflammatory responses in allergy and asthma. In the present study, we used a murine Aspergillus fumigatus inhalational model to mimic human disease. After observing in vivo that a robust B cell recruitment followed a massive eosinophilic egress to the lumen of the allergic lung and corresponded with the detection of low molecular mass HA (LMM HA), we examined the effect of HA on B cell chemotaxis and cytokine production in the ex vivo studies. We found that LMM HA functioned through a CD44-mediated mechanism to elicit chemotaxis of B lymphocytes, while high molecular mass HA (HMM HA) had little effect. LMM HA, but not HMM HA, also elicited the production of IL-10 and TGF-β1 in these cells. Taken together, these findings demonstrate a critical role for ECM components in mediating leukocyte migration and function which are critical to the maintenance of allergic inflammatory responses.

Keywords: Hyaluronan, Aspergillus fumigatus, B lymphocytes

Introduction

Asthma is a debilitating disease of the airways that affects over 300 million people globally (Manion, 2013). Asthmatic airways sensitized to a specific allergen respond aggressively to subsequent exposures, resulting in episodic asthma attacks that can be fatal. In the context of allergic asthma, sensitization to fungi often presents a severe clinical scenario that is difficult to treat and accounts for a disproportionately large number of emergency center visits and hospitalizations (Knutsen et al., 2012; Hogan and Denning, 2011; Umetsu and DeKruyff, 2006; Hamid and Minshall, 2000).

The hallmarks of chronic airway inflammation in patients with severe or persistent fungal asthma include the accumulation of activated eosinophils (Rosenberg et al., 2013; Ghosh et al., 2013; Chaudhary and Marr, 2011; Acharya and Ackerman, 2014; Wardlaw et al., 2000), neutrophils (Murdock et al., 2011), lymphocytes (Murdock et al., 2011; Ghosh et al., 2012a; Shreiner et al., 2012), and extracellular matrix components (ECM) components (Jiang et al., 2011). As a consequence of repeated and persistent inflammation, lung morphology eventually becomes altered even in mild forms of the disease, causing chronic dysfunction (Dagenais and Keller, 2009). Many of the acute and chronic features of clinical fungal asthma are recapitulated in the experimental model that we have developed in our laboratory in which sensitization with fungal extracts is followed by allergy challenge via inhaled Aspergillus (Hoselton et al., 2010; Schuh and Hoselton, 2013; Samarasinghe et al., 2011). We observe IgE production, eosinophilia, leukocyte recruitment, and pronounced peribronchial ECM changes that are exaggerated upon subsequent exposure to inhaled conidia (Ghosh et al., 2012a, 2013, 2014a; Chaudhary and Marr, 2011; Hoselton et al., 2010; Pandey et al., 2013).

ECM components are involved in the attachment of cells (Jiang et al., 2011; Oharazawa et al., 1999; Thannickal et al., 2003), tissue growth and repair (Jiang et al., 2011), proliferation and differentiation (Jiang et al., 2011; Oharazawa et al., 1999), cell migration and activation (Jiang et al., 2011; Oharazawa et al., 1999; Noble, 2002; McKee et al., 1996; Peck and Isacke, 1998), cell survival/delay of apoptosis (Jiang et al., 2011; Ruffell and Johnson, 2008), and chemo-taxis (Jiang et al., 2011; Noble, 2002) indicating the important role that ECM components play in the development and persistence of inflammation. Hyaluronan (HA), a non-sulfated glycosaminoglycan polymer and a major component of the ECM (Meyer and Palmer, 1934), undergoes dynamic regulation during inflammation (Jiang et al., 2007, 2011; Katoh et al., 2007; Laurent and Fraser, 1992; Lennon and Singleton, 2011; Toole, 2000; Ghosh et al., 2014b) and is synthesized by a wide variety of cell types, including stromal cells (Yue et al., 1978), fibroblasts (Kitchen and Cysyk, 1995; Acharya et al., 2008; Vistejnova et al., 2014), epithelial cells (Toshida et al., 2012), and smooth muscle cells (Deudon et al., 1992). HA exists as a high molecular mass (HMM) linear polymer in excess of 107 Da in the native form found in the lung (Noble, 2002). Under conditions of inflammation, HMM HA is broken down into low molecular mass HA (LMM HA) (35–400 kDa), which exhibits pro-inflammatory effects on cells and tissues (Jiang et al., 2011; Yang et al., 2012; Noble and Jiang, 2006; Dentener et al., 2005; Papakonstantinou and Karakiulakis, 2009; Singleton and Lennon, 2011; Stern, 2003). As HMM HA is reconstituted, it blocks the pro-inflammatory effects of LMM HA and supports tissue integrity (Jiang et al., 2007, 2011; Yang et al., 2012; Petrey and de la Motte, 2014; Sokolowska et al., 2014; Toole, 2004).

HA binding proteins are expressed on structural and immune cells, they include: CD44 (Entwistle et al., 1996; Lesley et al., 1993), the receptor for hyaluronan-mediated motility (RHAMM) (Pilarski et al., 1994; Toole, 1990), tumor necrosis factor-α-stimulated glycoprotein-6 TSG-6 (Getting et al., 2002; Maier et al., 1996; Swaidani et al., 2013), the lymphatic vessel endothelial hyaluronan receptor-1 (LYVE-1) (Banerji et al., 1999), and the toll-like receptors (TLRs) (Jiang et al., 2007, 2011; Garantziotis et al., 2010). CD44 is the best characterized HA receptor. It is a structurally variable and multifunctional glycoprotein whose expression may be induced on most cell types (Jiang et al., 2007, 2011; Pure and Cuff, 2001; Rothenberg, 2003). There is a growing body of evidence that HA/CD44 binding regulates both lymphoid and myeloid cells (Jiang et al., 2011; Ruffell and Johnson, 2008; Katoh et al., 2007; Rafi et al., 1997; Do et al., 2004; Cheng et al., 2013). In B lymphocytes, CD44 facilitates adhesion to HA and proliferation in the spleen (Ghosh et al., 2014b; Rafi et al., 1997; Vasconcellos et al., 2010). However, the contribution of HA/CD44 to B lymphocyte migration and activation in the context of pulmonary responses to fungus has not been investigated.

In the present study, we observed a temporal association between LMM HA in the airway lumen after eosinophil egress and B lymphocyte recruitment to the allergen-challenged lung. We hypothesized that eosinophil migration through the HMM HA surrounding the airways generates pro-inflammatory LMM HA that impacts the movement and function of B cells in the context of the allergic lung. To test our hypothesis we used ex vivo cultures of B cells from allergic mice to determine the extent to which HA/CD44 binding facilitates B lymphocyte migration and the effect of HA on the production of pro-allergy cytokines by B lymphocytes. Our data show that after fungal challenge B lymphocytes are recruited to the lung after eosinophil egress to the lumen at a time point when LMM HA levels are readily detected in the lung. We show that LMM HA, acting mainly through the CD44 receptor, has a pronounced effect on ex vivo B lymphocyte migration and production of the cytokines transforming growth factor-1 (TGF-β1) and IL-10. The results presented in this study reveal previously unrecognized roles of B lymphocytes and LMM HA during the inflammatory process of fungus-induced allergic processes. These findings expand our understanding of the contribution of residential matrix components in asthma pathogenesis and have the potential to inform therapeutic advances for patients with asthma.

Materials and methods

Ethics statement

All experiments were performed in accordance with the Office of Laboratory Animal Welfare guidelines and were approved by the North Dakota State University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee, Fargo, ND, USA.

Experimental animals

C57BL/6 male and female mice (6–9 weeks of age) were obtained from the Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME, USA). Animals were housed on Alpha-dri™ paper bedding (Shepherd Speciality Papers, Watertown, TN, USA) in micro filter-topped cages (Ancare, Bell-more, NY, USA) in a specific pathogen-free facility with ad libitum access to food and water.

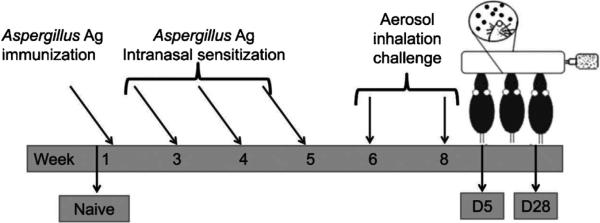

Allergen sensitization and challenge by a nose only inhalation model

Animals were sensitized as per published protocol (Hoselton et al., 2010). Briefly, mice were sensitized with 10 μg of Aspergillus fumigatus antigen (Greer Laboratories, Lenoir, NC, USA) in 0.1 ml sterile phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) mixed with 0.1 ml of Imject Alum (Pierce, Rockford, IL, USA), which was injected subcutaneously (0.1 ml) and intraperitoneally (0.1 ml). After two weeks, mice were given a series of three, weekly 20 μg doses of A. fumigatus antigen in 20 μl of PBS by an intranasal route. Animals were challenged as previously described with a 10 min, nose-only inhalation exposure to live A. fumigatus conidia (strain NIH 5233) (Hoselton et al., 2010). Each anesthetized mouse was placed supine with its nose in an inoculation port and allowed to inhale live conidia for 10 min. This challenge was repeated 2 weeks after the first. Mice were then separated into groups of five for analysis at days 5 and 28 after the second aerosol challenge. These time points were chosen based on previously published results showing that B lymphocyte recruitment peaks 5 days after the second conidia challenge (Ghosh et al., 2012a) and that changes to the lung architecture continue to accrue through at least day 28 after the second inhalation of fungal conidia (Ghosh et al., 2014c). Naïve controls were age-matched mice that were neither sensitized nor challenged. The experimental protocol is depicted in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Sensitization, challenge, and analysis schedule for the A. fumigatus murine model of allergic asthma. Mice were sensitized to A. fumigatus extract via a series of injections and intranasal inoculations, after which they were exposed to 2, nose-only inhalation doses of live conidia 2 wk apart. Groups of animals were assessed at prescribed time points after allergen challenge.

Serum and BAL sample collection

Approximately 500 μl of blood was collected from each mouse via ocular bleed and centrifuged at 13,000 × g for 10 min to yield serum. Bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) was performed on five mice per group with 1.0 ml PBS. The BAL contents from each animal were centrifuged at 2000 × g for 5 min to separate cells from fluid. Cells were resuspended in 200 μl of PBS, cytospun (Shandon Scientific, Runcorn, UK) onto glass microscope slides, and counted after staining with Quik-Dip differential stain (Mercedes Medical; Sarasota, FL, USA). The mean number of each cell type per high-powered field (hpf, 1000×) was determined by morphometric analysis. Serum and BAL fluid were stored at −20 °C until use.

Quantification of HA in serum and BAL

Total HA levels were quantified via specific competitive ELISA in undiluted serum and BAL fluid samples according to the manufacturer's guidelines (Echelon Biosciences, Salt Lake City, Utah, USA). The HA detection range of the kit was 12.5–3200 ng/ml. The kit detects a minimum HA size of 10 disaccharide units (4500 Da).

Tissue harvest and staining

Paraffin-embedded lungs were sectioned at 5 μm and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (Thermo Scientific, Rockford, IL, USA) and Gomori's trichrome (Richard-Allan Scientific, Kalamazoo, MI, USA) stains to determine inflammation and subepithelial collagen deposition, respectively. Immunostaining for HA was performed as previously described (Ghosh et al., 2014c; Simpson et al., 2002).

HA size determination

HA molecular mass was determined in lung samples as described previously (Cheng et al., 2013; Bhilocha et al., 2011; Eldridge et al., 2011; Liang et al., 2011). Briefly, right lungs from mice at each time point were homogenized in 1.0 ml PBS. The samples at each time point were pooled and concentrated with a centrifugal filter (10,000 Da cut-off; Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA). The lung samples were then digested with Pronase (100 U/ml, Pronase from Streptomyces griseus; Sigma–Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) at 55 °C for 2 h, followed by inactivation of protease activity by boiling the samples for 10 min. Following pronase digestion, the samples were digested with 6 μl of 2 U/μL DNase (Ambion, Austin, TX, USA) and 6 μl of 1.28 μg/μl RNase (Roche, Indianapolis, IN, USA) as described (Cheng et al., 2013). After nuclease digestion, we divided 80 μl of our sample from various time points in half by transferring 40 μl to another tube. Added 4 μl of Streptomyces hyaluronidase to ½ of your sample and incubated overnight at 37 °C. Heat inactivated enzymes on a boiling water bath for 5 min. Concentrated samples were then analyzed by electrophoresis on a 0.8% agarose gel. HA molecular weight standards (Select-HA™ LoLadder, and HiLadder; Hyalose, Oklahoma City, OK, USA) were run on the same gel for comparison. Electrophoresis was carried out at room temperature at a constant voltage of 80 V for 3 h. Immediately after the run, the gel was stained with 0.005% Stain-All (Sigma–Aldrich) in 50% ethanol. The gel was stained overnight under light-protective cover at room temperature. For destaining, the gel was transferred to 10% ethanol solution. Final destaining of any residual background was accomplished by placing the gel on a light box for a few minutes. Agarose gels were photographed on an Alpha Innotech Imaging System (ProteinSimple, Santa Clara, CA, USA).

Characterization and purification of B lymphocytes

Mice were anesthetized using sodium pentobarbital (Butler, Columbus OH; 100 mg/kg of mouse body weight), and lungs and spleens were removed from five animals to prepare the single cell suspensions. For lung preparations, minced lungs were subjected to collagenase IV (Sigma–Aldrich) digestion in DMEM at 37 °C for 1 h with gentle agitation. The cells were then dispersed through a 10 ml syringe and passed through a 40 μm cell strainer (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA). The cells were washed with sterile PBS twice before they were treated with ammonium chloride cell lysis buffer (ACLB) to remove the red blood cells. To prepare a single cell suspension of splenocytes, spleens were perfused with DMEM. Spleen cells were washed with sterile PBS and treated with ACLB to lyse red blood cells. Lung and spleen cell preparations were counted and re-suspended in PBS with 1% BSA (Sigma Aldrich) to a final concentration of 1 × 107 cells/ml. Fc receptors were blocked with 1 μg of anti-mouse CD16/CD32 per 106 cells (eBioscience, San Diego, CA, USA) for 10 min on ice.

The following Abs were used for phenotypic characterization of B lymphocytes using flow cytometry: FITC-anti-CD19, PE-anti-CD44, PE-anti-CD23, PE-anti-CD49d (eBioscience) and PE-Cy™ 7 anti-CD11a (BD Biosciences). The samples were stained with labeled Abs (1 μg/million cells) for 30 min in the dark at 4 °C and then washed with PBS 1% BSA twice before analyzing using a BD FACSCalibur (BD Biosciences) or an Accuri C6 flow cytometer (Accuri Cytometers, Ann Arbor, MI, USA). The data was analyzed using FlowJo software (Tree Star, Ashland, OR, USA).

For the purification of B lymphocytes, spleen and pooled lung cells were incubated with 0.0625 μg of FITC-anti-CD19 antibody per million cells for 30 min in the dark at 4 °C (eBioscience). The cells were then washed with sterile PBS and incubated with 10 μl of anti-FITC Microbeads per 107 cells (Miltenyi Biotec, Auburn, CA, USA), and CD19-positive B lymphocytes were positively selected using the quadro MACS system with LS columns (Miltenyi Biotec) according to the manufacturer's guidelines. After sorting, B lymphocytes were re-suspended in DMEM supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 2 mM L-glutamine, 100 U/ml penicillin, 100 μg/ml streptomycin, 0.25 μg/ml amphotericin B, and 50 μM 2-mercaptoethanol to a final concentration of 2 × 107 cells/ml. The purity of the samples was 90–95% via BD FACSCalibur (BD Biosciences) flow cytometry, and data was analyzed using FlowJo software. These cells were used for chemotaxis and cell culture experiments.

Chemotactic activity of low and high molecular mass HA and ex vivo culture of B lymphocytes

To assess the chemotactic activity of LMM HA (40–60 kDa) and HMM HA (351–600 kDa) (Lifecore Biomedical LLC, Chaska, MN, USA), isolated spleen B lymphocytes were subjected to an in vitro chemotaxis assay in a 96-well modified Boyden chamber (ECM512, Millipore Corporation, Billerica, MA, CA, USA). The LMM HA and HMM HA used for the chemotaxis assay were cell culture grade and certified endotoxin free. Purified B lymphocytes were re-suspended at 2 × 107 cells/ml in DMEM and each well was seeded with 5 × 105 B cells (Bhilocha et al., 2011). CD44 was blocked by pre-incubating B lymphocytes with 50 μg/ml of anti-CD44 neutralizing Ab (clone IM7; BD Biosciences) for 2 h (Vachon et al., 2006). B lymphocytes were also pre-incubated with 50 μg/ml isotype control Ab (Purified Rat IgG2b) for 2 h. Purified B lymphocytes (5 × 105 cells) were added to each well in the top filter plate portion of the assembly, and 150 μl of a 400 μg/ml solution of LMM HA and HMM HA (Zaman et al., 2005; Tamoto et al., 1994) was added to the respective bottom wells. The chamber was incubated at 37 °C with 5% CO2 and constant humidity for 16 h. Migrated cells were detached, lysed, and labeled with a CyQuant GR dye that exhibited strong fluorescence when bound to cellular nucleic acids. Sample fluorescence was measured with a Synergy HT fluorescence microplate reader (BioTek, Winooski, VT, USA) using a 480/520 nm excitation and emission filter set. For the chemotaxis assay we used CXCL13 (100 ng/ml) as a positive control (Rupprecht et al., 2009).

For B lymphocyte ex vivo culture experiments, purified B lymphocytes from the spleen and lung (1 million cells/50 μl) were seeded in a 96-well cell culture plate (Corning, New York, USA). Blocking of CD44 was done as above with 50 μg/ml anti-CD44. B lymphocytes were also pre-incubated with 50 μg/ml isotype control Ab (Purified Rat IgG2b). One hundred-fifty microliters of LMM HA and HMM HA (0.5 mg/ml) (Rafi et al., 1997) in complete medium was added to the wells containing B lymphocytes for a total volume of 200 μl. The plate was cultured in a humidified 37 °C incubator with 5% CO2 for 48 h.

Antibody and cytokine ELISA

IgE, IL-4, TGF-β1, and IL-10 levels were measured using ELISA kits purchased from eBioscience as per manufacturer's guidelines (eBioscience, San Diego, CA, USA).

Statistical analysis

Allergic C57BL/6 wild type animals were compared to their respective naïve controls at each time point. Results are expressed as the mean ± SEM. Data were evaluated with GraphPad Prism software (San Diego, CA) using an unpaired, Student's two tailed t-test with Welch's correction to determine statistical significance. A value of *p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

The protocol used for the development of allergic airway disease is shown in Fig. 1. In allergic mice, we first ascertained that the standard hallmarks of airway disease were present. Airway hyper-responsiveness, elevated IgE in BAL fluid and serum, and elevated serum IL-4 were observed days 5 after the second conidia inhalation in allergic animals, as compared to naïve animals (data not shown). By day 28, after the second conidia challenge, the AHR, IgE, and IL-4 returned to naïve levels. This is consistent with our previously published work with this model (Ghosh et al., 2012a,b, 2014c).

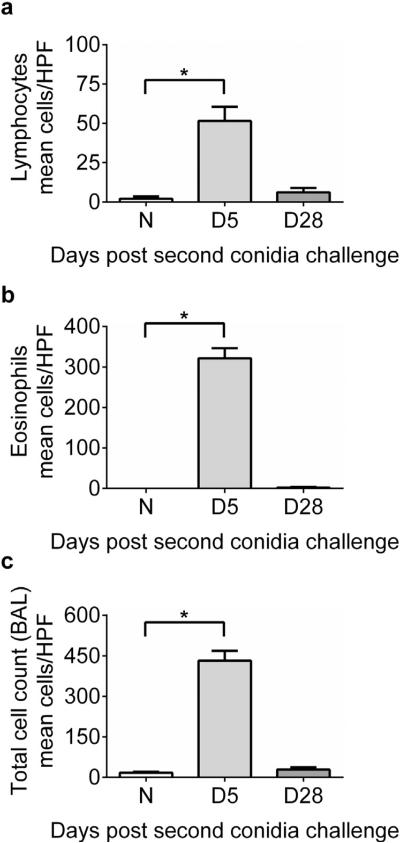

Inhalational fungal challenge with A. fumigatus increases recruitment of lymphocytes and eosinophils to the airway

Morphometric identification of monocytes/macrophages, eosinophils, neutrophils, and lymphocytes was performed to estimate the relative makeup of the cellular inflammation and to monitor leukocyte egress into the airway lumen (Fig. 2). Lymphocytes (Fig. 2a) made up ~16% and eosinophils (Fig. 2b) ~74% of the total inflammation at day 5 after conidia challenge, dominating the total leukocytic inflammation (Fig. 2c).

Fig. 2.

Effect of inhalation of A. fumigatus conidia on lymphocyte and eosinophil inflammation in allergic C57BL/6 mice. Airway inflammation marked by the presence of lymphocytes (A) and eosinophils (B) in naïve and allergic animals. (C) Represents total inflammatory cells in the BAL compartment of naïve and allergic C57BL/6 mice. Data were analyzed using an unpaired Student two-tailed t-test with Welch correction. All values are expressed as the means ± SEM (n = 4–5 mice/group). *p < 0.05. Data shown are representative of two independent experiments.

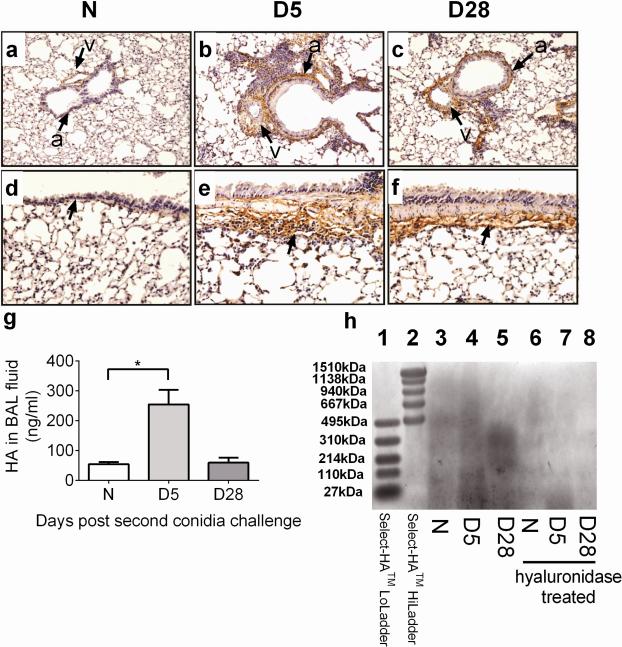

The deposition of HA is increased in perivascular and peribronchial spaces, and LMM HA levels are elevated in the BAL fluid of allergen challenged mice after allergen challenge

Given the recognized role of inflammatory cells and HA in disease processes including COPD and asthma pathogenesis, we investigated the influx of inflammatory cells with HA levels in a model of fungus-induced pulmonary inflammation. Immunohistochemistry revealed that HA deposition was increased around airways (a) and blood vessels (v) after challenge in areas where inflammatory cells were present as compared to naïve lungs (Fig. 3a, b, d, and e). Basement membrane, areas underlying the basal myocytes, and surrounding inflammatory cells showed intense HA staining at day 5 (Fig. 3e). By day 28, HA was still clearly evident around blood vessels adjacent to the airways (Fig. 3c) and the basement membrane (Fig. 3f).

Fig. 3.

Effect of inhalation of A. fumigatus conidia on HA deposition and LMM HA levels. (A–F) HA deposition around the small (A–C) and large airways (D–F) is shown for lungs from naïve (unchallenged) mouse and A. fumigatus sensitized and challenged mice [a = airway, v = blood vessel]. ELISAs were carried out to measure HA levels in C57BL/6 mice after fungal challenge. (G) HA levels in the BAL fluid of naïve and allergic animals. (H) HA size in the lung of naïve and allergic animals. Data were analyzed using an unpaired Student two-tailed t-test with Welch correction. All values are expressed as the means ± SEM (n = 4–5 mice/group). *p < 0.05. Data shown are representative of two independent experiments.

LMM HA was increased in the lung of allergic animals at day 5 after the second conidia challenge as compared to naïve mice (Fig. 3g), and this HA was predominantly of LMM HA (Fig. 3h), indicating HA breakdown or HA synthesis. By day 28 after challenge, HA levels were higher than naïve controls, and this HA was predominantly of HMM HA (Fig. 3g). We have also shown previously that there is a parallel increase and co-localization of HA and collagen deposition in the allergic lungs after exposure to the inhaled fungus, suggesting that the regulation of these ECM components is linked (Ghosh et al., 2014c). This may explain the increased levels of HA at day 28 than naïve controls as peribronchial fibrosis marked with excessive collagen deposition is elevated at this time point.

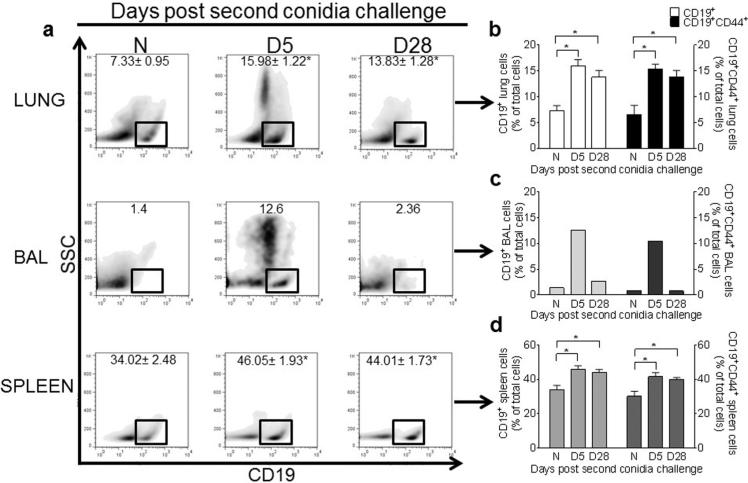

CD19+ and CD19+ CD44+ B lymphocyte numbers are increased in the allergic lung, BAL, and spleen of A. fumigatus-challenged mice

We next examined whether B lymphocytes were a significant component of the inflammation associated with allergic disease, when HA levels are elevated in the lung and BAL fluid of allergic animals. We had previously noted that B cell recruitment to the allergic lung peaks at day 5 after 2 inhalation challenges (Ghosh et al., 2012a,b). In this study, we observed significant increases in CD19+ B lymphocytes in the lung (as previously reported), as well as the BAL and spleen at day 5, as compared to naïve controls (Fig. 4a–d). By day 28, the number of B lymphocytes in the BAL had returned to levels comparable with naive controls (Fig. 4a and c), but remained elevated in the lung tissue and spleen (Fig. 4b and d).

Fig. 4.

Inhalation of A. fumigatus conidia increases CD19+ and CD19+CD44+ B cells in the lung, BAL, and spleen of allergic mice. Flow cytometry was used to analyze density plots (SSC vs CD19) of cells isolated from the lungs, BAL (pooled by group), and spleens of naïve and allergic C57BL/6 mice (A), and the percentage of CD19+ and CD19+CD44+ B cells (B–D) was calculated. Data were analyzed using an unpaired Student two-tailed t-test with Welch correction. All values are expressed as the means ± SEM (n = 4–5 mice/group). *p < 0.05. Data shown are representative of two independent experiments.

Our next step was to determine whether these B lymphocytes present in the allergic animals expressed the HA receptor CD44. After A. fumigatus conidia challenge, we analyzed the CD19+ B lymphocyte populations by flow cytometry for CD44 expression (Fig. 4). CD19+CD44+ lung B cells were increased at day 5 after two conidia challenges (Fig. 4b), as compared to controls. CD19+CD44+ B cells were also increased in the BAL and spleen of allergic animals (Fig. 4c and d). However, by day 28 after the second conidia challenge, the number of CD19+CD44+ B cells returned to naïve controls in the BAL (Fig. 4c). This time point coincides with the resolution of inflammation and low HA levels in BAL fluid (Fig. 3).

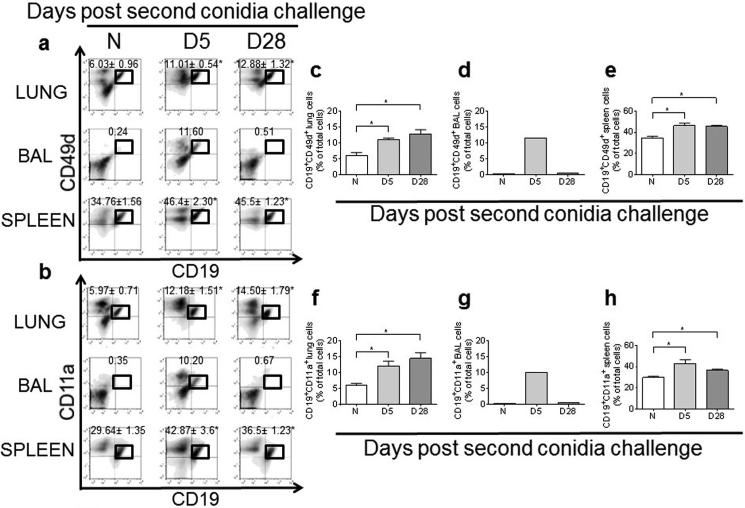

CD19+ CD49d+ and CD19+ CD11a+ B lymphocyte numbers are increased in the lung, BAL, and spleen of A. fumigatus-challenged mice

The integrin molecules CD49d and CD11a are required for interaction with ligands on the endothelial surface to arrest and extravasate to the site of infection/tissue injury. To determine whether B lymphocytes in the lung, BAL, and spleen up-regulate or express these molecules, we analyzed B lymphocyte populations of naïve and allergic animals with flow cytometry. We found that the percentage of CD19+CD49d+ and CD19+CD11a+ B lymphocytes was increased in the allergic lung, BAL, and spleen at day 5 after the second conidia challenge (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

A. fumigatus conidia inhalation increases the number of activated CD19+ B cells in the allergic lung, BAL, and spleen. Lung, BAL, and spleen CD19+ B cells were evaluated by flow cytometry for CD49d (A) and CD11a (B) expression, and the percentage of CD19+ CD49d+ (C–E) and CD19+ CD11+ B cells (F–H) was calculated in the lung, BAL (pooled samples), and the spleen of naïve and allergic C57BL/6 mice. Data were analyzed using an unpaired Student two-tailed t-test with Welch correction. All values are expressed as the means ± SEM (n = 4–5 mice/group). *p < 0.05. Data shown are representative of two independent experiments.

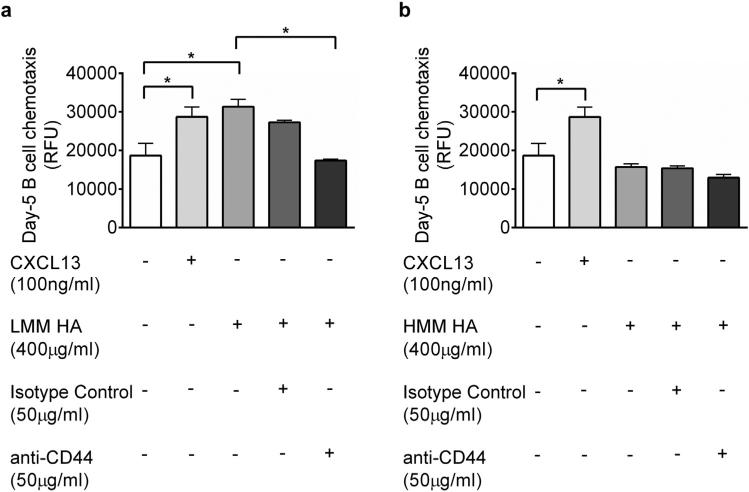

CD44 is necessary for LMM HA-mediated chemotaxis of B lymphocytes

In this fungal model, we see an influx of B lymphocytes in the allergic lung at day 5 after the second conidia challenge (Fig. 4). To investigate the recruitment of B lymphocytes after fungal challenge, we determined the role of HA and CD44 in HA-mediated motility of B lymphocytes. Spleen B lymphocytes were isolated and a modified Boyden chamber assay was performed using LMM HA or HMM HA as the chemoattractant. Spleen B lymphocytes were isolated for the chemotaxis assay since the spleen compartment is dominated by B2 lymphocytes (Ghosh et al., 2012b; Hsueh et al., 2002) and all CD19+ spleen B cells express the CD44 receptor (Fig. 4). When treated with LMM HA, B lymphocytes isolated from the spleens of allergic animals 5 days after the second conidia challenge exhibited increased chemotaxis (Fig. 6a). Blocking CD44 completely abrogated this effect (Fig. 6a). HMM HA had no effect on the chemotactic activity of B lymphocytes (Fig. 6b).

Fig. 6.

LMM-HA effects B cell movement through a CD44-dependent mechanism. Using a modified Boyden chamber, chemotactic activity towards LMM HA (A) and HMM HA (B) was measured for CD19+ spleen B cells isolated from mice 5 days after conidia inhalation with and without CD44 blocking antibodies. Data were analyzed using an unpaired Student two-tailed t-test with Welch correction. All values are expressed as the means ± SEM (n = 5 mice/group). *p < 0.05. This result is an outcome of two independent experiments.

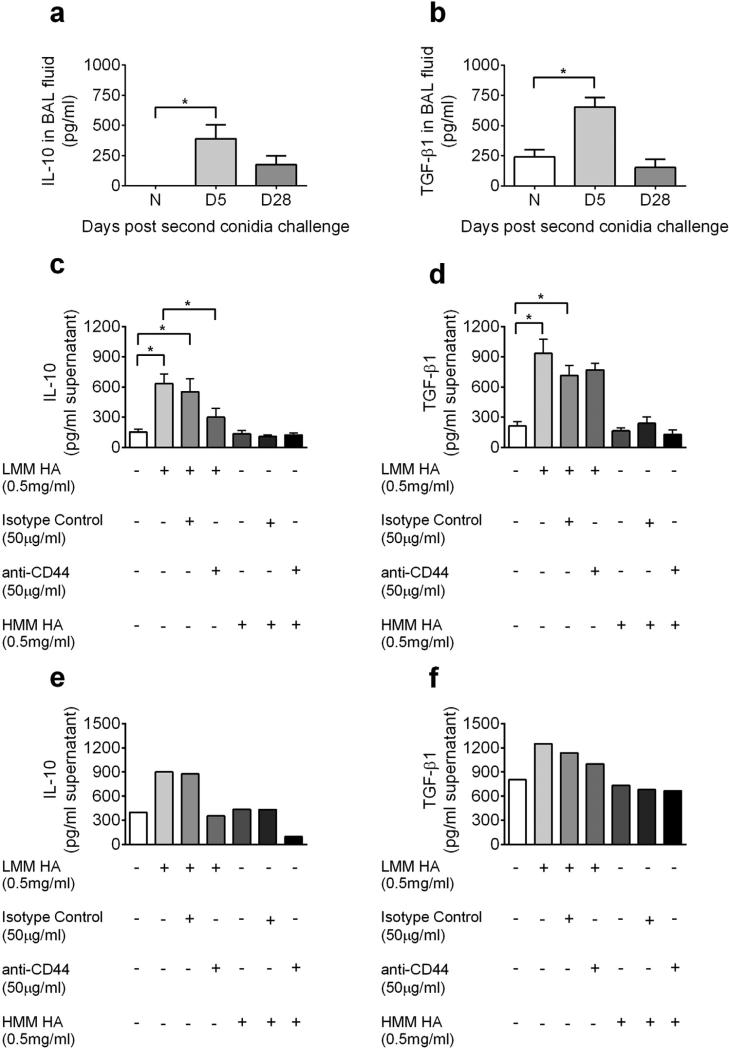

LMM HA mediates IL-10 and TGF-β1 production by B lymphocytes

HA and collagen deposition closely mirror each other in the context of the ECM (Cheng et al., 2013; Ghosh et al., 2014c), and pro-allergy and pro-fibrotic cytokines have been implicated in the process of fibrotic airway wall remodeling/tissue repair process. In in vivo experiments, we found that BAL IL-10 and TGF-β1 was elevated in the allergic lung as compared to naïve lungs (Fig. 7a and b). To determine if HA acting on B cells may be contributing to the production of IL-10 and other important cytokines, we isolated B cells from allergic lung and spleen 5 days after the second conidia inhalation and cultured them for 48 h with LMM HA or HMM HA. B cells produced both IL-10 and TGF-β1 after stimulation with LMM HA, while HMM HA had no effect (Fig. 7c–f). The production of IL-10 was abrogated by blocking CD44 (Fig. 7c and e); however, blocking CD44 did not have an effect on TGF-β1 production (Fig. 7d and f, Fig. 8).

Fig. 7.

The effect of A. fumigatus conidia challenge/HA fragments on IL-10 and TGF-β1 production. IL-10 (A) and TGF-β1 (B) levels were assessed by ELISA in the BAL fluid of naïve and allergic animals. Spleen (C and D) and lung (E and F) B cells were harvested from wild-type C57BL/6 mice at day 5 and treated with LMM HA or HMM HA with or without a neutralizing CD44 antibody. Supernatant was harvested 48 h later, and IL-10 (C and E) and TGF-β1 (D and F) production was assessed by ELISA. Data were analyzed using an unpaired Student two-tailed t-test with Welch correction. All values are expressed as the means ± SEM (n = 5 mice/group). *p < 0.05. No statistics are shown for cytokine production by lung B cells as the lung B cells from five mice from D5 time point were pooled and run as a single sample. Data shown are representative of two independent experiments.

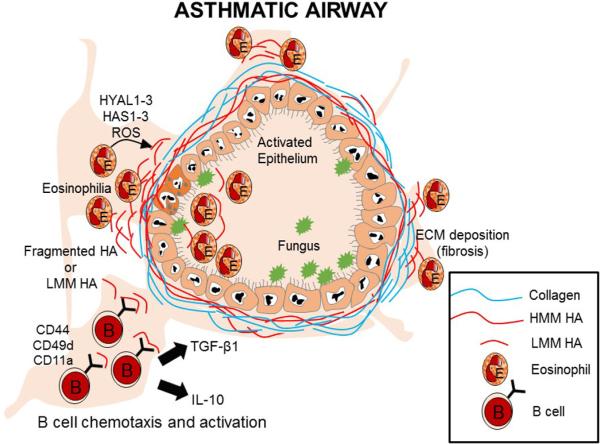

Fig. 8.

Hypothetical model for LMM HA regulation of B lymphocyte recruitment and function in the allergic lung. At sites of chronic inflammation in the lung combined actions of HASs, HYALs, and ROS generated by eosinophils during the asthmatic response may be breaking down LMM HA to HMM HA. This LMM HA would promote the preferential recruitment of B lymphocytes in a CD44 dependent manner. These B lymphocytes in addition to CD44 express the activation markers (CD49d and CD11a) which would promote the extravasation of B lymphocytes to the site of tissue injury. In the allergic lung these B cells will interact with LMM HA and will promote the production of pro-allergy cytokines IL-10 and TGF-β1.

Discussion

In the current work, we provide new evidence that LMM HA generated at sites of chronic inflammation may promote a cellular B cell program that supports an allergy phenotype. To our knowledge, this is the first time that LMM HA, but not HMM HA, has been shown to promote chemotaxis in B cells in allergic asthma. Further, when B cells were stimulated with LMM HA ex vivo, B lymphocytes produced the pro-allergy cytokines IL-10 and TGF-β1. Our findings extend the growing body of evidence that shows the ECM's effect – and in particular LMM HA's effect – at the local site of tissue injury (Jiang et al., 2011; Noble and Jiang, 2006).

Under disease conditions such as asthma and COPD, HA is broken down to LMM HA (Jiang et al., 2011; Noble and Jiang, 2006), which can be detected in the BAL fluid (Jiang et al., 2011; Sahu and Lynn, 1978; Sahu, 1980; Necas et al., 2008). Previously, we have shown that HYAL1 and HYAL2 gene expression is significantly increased in the allergic mouse lung at day 5 after the second conidia challenge as compared to naïve controls, suggesting that these hyaluronidases are responsible for the rapid hydrolysis of HMM HA to LMM HA in this model system (Ghosh et al., 2014c). We have also shown that there is a parallel increase and co-localization of HA and collagen deposition in the allergic lungs after exposure to the inhaled fungus, suggesting that the regulation of these ECM components is linked (Ghosh et al., 2014c).

CD44 is important for lymphopoiesis, lymphocyte homing, T cell activation, and metastasis (Ruffell and Johnson, 2008; Lesley et al., 1993; DeGrendele et al., 1997). Non-infectious lung injury in CD44-deficient mice results in sustained inflammation of the alveolar interstitium, LMM HA accumulation at 14 days after bleomycin injury, impaired clearance of neutrophils in association with decreased TGF-β1 activation and increased mortality (Jiang et al., 2007; Zaman et al., 2005), suggesting a role of CD44 in regulating inflammation, HA clearance, and cytokine production. CD44 is a prominent HA receptor and a prime target for mediating the differential responses to low and high molecular mass HA. However, CD44 expression and engagement on B lymphocytes is not yet well defined (Rafi et al., 1997; Murakami et al., 1990). Activated B lymphocytes, particularly those stimulated with IL-5, bind HA with higher affinity than naïve B cells (Lesley et al., 1993; Vasconcellos et al., 2010; Murakami et al., 1990). In addition, IFN-γ inhibits HA/CD44 interactions in naive B lymphocytes (Marko Kryworuchko, 1999). Our ex vivo results show a role for CD44 in enabling B lymphocyte migration to LMM HA. We hypothesize that in the allergic model, elevated IL-5 and IL-4 levels may function to promote B lymphocyte interaction with HA via CD44. Similarly, elevated IL-10 levels may function to limit IFN-γ production and stimulate B lymphocyte interaction with HA via CD44.

Increased expression of the integrin molecules CD49d and CD11a allows lymphocytes to interact with ligands on endothelial cells and infiltrate into areas of allergic inflammation to mediate immune responses (McDermott and Varga, 2011; Lang et al., 2013). In this model of fungus-induced airway disease, we observe an increase in the total percentage of CD19+CD49d+ and CD19+CD11a+ B lymphocytes in the allergic lung, reiterating the role of these integrin molecules, along with CD44, in B lymphocyte migration to the site of chronic inflammation/tissue injury. The mechanism through which these molecules mediate B cell migration in the allergic lung remains to be shown in vivo.

Our work and that of others have shown that B lymphocytes make up a significant component of inflammation associated with asthma, indicating a potential role in the deleterious effects associated with that inflammation (Ghosh et al., 2012a,b; Hamelmann et al., 1997; Jungsuwadee et al., 2004). Although the chemokines involved in neutrophil and eosinophil recruitment in asthma are well recognized, few studies have evaluated the recruitment of B lymphocytes into the allergic lung (Cheng et al., 2011, 2013). In the current study, we show ex vivo evidence that the ECM itself could promote B lymphocyte migration in times of HA hydrolysis.

An important outcome of this study is the increased release of IL-10 and TGF-β1 by ex vivo cultured B lymphocytes in response to LMM HA. IL-10 production by B lymphocytes was dependent on CD44 indicating that CD44 may be involved in the production of this Th2 cytokine. On the contrary, TGF-β1 production by B lymphocytes was independent of CD44, indicating that other receptors may be involved in regulating this process. It is possible that Toll-like receptors 2 and 4 (TLR-2 and TLR-4), present on B lymphocytes, provide the signals for TGF-β1 production, as TLR-2 and TLR-4 have been shown to interact with fragmented HA (Jiang et al., 2011). The mechanisms responsible for the differential functions of low versus high molecular mass HA are still unclear, but may be related to an increased binding affinity of the smaller molecule that allows more efficient CD44 receptor crosslinking (Yang et al., 2012; Ohkawara et al., 2000).

Increased IL-10 production is associated with increased levels of total and specific immunoglobulins (IgE, IgG1, and IgA) and airway remodeling, reflecting a role of IL-10 in promoting a Th2 response to A. fumigatus antigens (Dagenais and Keller, 2009; Latge, 1999). Alternatively, IL-10 can suppress the secretion of other cytokines and control cellular activation, consistent with modulating pathology (Donaldson et al., 2013). In addition, IL-10 permits the Foxp3-inducing capacity of TGF-β1 and hence could further elevate Treg differentiation (Fantini et al., 2004). Like IL-10, TGF-β1 is considered as an immune suppressive cytokine, and as a result local production may help modulate asthma (Makinde et al., 2007). However, its role in allergic asthma is clearly more complex. The combination of IL-4 and TGF-β1 has been shown to induce IL-9 secreting CD4+ T cells, a cytokine known to exacerbate asthmatic symptoms (Dardalhon et al., 2008). Further, TGF-β1 has a clear role in causing tissue remodeling changes that are associated with decreased airway responsiveness in chronic asthma.

Airway wall remodeling is a particularly unyielding symptom of chronic airway inflammation due to allergy. TGF-β1 has long been associated with the epithelial alterations, subepithelial fibrosis, and airway smooth muscle changes that characterize remodeling (Halwani et al., 2011; Shifren et al., 2012; Vignola et al., 2001). We hypothesize that during disruption of the ECM, whether from cells moving from the parenchyma to the lumen or microbial attack from the lumen, normally immunologically inert HMM HA is hydrolyzed and takes on a chemoattractant role, functioning to both attract and activate B cells in an area where they can most effectively enact a fibrotic repair mechanism. With subsequent rounds of allergen inhalation, this ‘repair’ is reinforced until intractable fibrosis results. This hypothesis will need to be tested in vivo and is the topic of ongoing research in our laboratory.

A variety of factors have been linked to increased HA synthesis, including prostaglandins and a multitude of cytokines many of which have roles in asthma (Lennon and Singleton, 2011; Petrey and de la Motte, 2014; Cheng et al., 2013). Likewise, there are several possible pathways that may be involved in the degradation of HA in the asthmatic lung (Agren et al., 1997; Atmuri et al., 2008). The stimulus for LMM HA accumulation in this model is difficult, as almost every cell has the capacity to produce HA and the balance of competing HASs and HYALs is critical to overall HA deposition (Jiang et al., 2011; Katoh et al., 2007; Cheng et al., 2011, 2013; Ghosh et al., 2014c).

In conclusion, these results support a novel localized immune modulation mediated by B lymphocytes when they interact with LMM HA generated at sites of allergic inflammation after the inhalation of fungal conidia. Our data suggest that LMM HA can function as an important signaling molecule for B lymphocyte movement and cytokine production, which are critical to the maintenance of allergic inflammatory responses. Further studies examining HA's role in mediating cellular responses may help to develop targets for treatment in patients with severe asthma due to fungal sensitization.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank Dr. Pawel Borowicz, co-Director of the Advanced Imaging and Microscopy Core Laboratory at NDSU, for his help with imaging using the Zeiss Z1 AxioObserver inverted microscope. We also thank Jessica Ebert for critical reading of the manuscript.

Funding source

These studies were funded by grants from the NIH (1R15HL117254-01 to J.M.S. and 1R15AI101968-01A1 to G.P.D.).

Footnotes

Author contributions

SG: Study conception and design, data acquisition, analysis and interpretation, and drafting and editing the manuscript; SAH and SG: FCS data acquisition and FlowJo analysis; JC and JBM: HA staining, analysis and interpretation; SBW, JBM, and GPD: HA size determination; JMS: fungal asthma model, study conception and design, and editing the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of North Dakota State University or the granting agencies.

Conflicts of interest

The authors report no conflicts of interest regarding the publication of this paper.

References

- Acharya KR, Ackerman SJ. Eosinophil granule proteins: form and function. J. Biol. Chem. 2014;289(25):17406–17415. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R113.546218. http://dx.doi.org/10.1074/jbc.R113.546218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Acharya PS, Majumdar S, Jacob M, Hayden J, Mrass P, Weninger W, et al. Fibroblast migration is mediated by CD44-dependent TGF beta activation. J. Cell Sci. 2008;121(Pt 9):1393–1402. doi: 10.1242/jcs.021683. http://dx.doi.org/10.1242/jcs.021683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agren UM, Tammi RH, Tammi MI. Reactive oxygen species contribute to epidermal hyaluronan catabolism in human skin organ culture. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 1997;23(7):996–1001. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(97)00098-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atmuri V, Martin DC, Hemming R, Gutsol A, Byers S, Sahebjam S, et al. Hyaluronidase 3 (HYAL3) knockout mice do not display evidence of hyaluronan accumulation. Matrix Biol. 2008;27(8):653–660. doi: 10.1016/j.matbio.2008.07.006. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.matbio.2008.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banerji S, Ni J, Wang SX, Clasper S, Su J, Tammi R, et al. LYVE-1, a new homologue of the CD44 glycoprotein, is a lymph-specific receptor for hyaluronan. J. Cell Biol. 1999;144(4):789–801. doi: 10.1083/jcb.144.4.789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhilocha S, Amin R, Pandya M, Yuan H, Tank M, LoBello J, et al. Agarose and polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis methods for molecular mass analysis of 5- to 500-kDa hyaluronan. Anal. Biochem. 2011;417(1):41–49. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2011.05.026. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ab.2011.05.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaudhary N, Marr KA. Impact of Aspergillus fumigatus in allergic airway diseases. Clin. Transl. Allergy. 2011;1(1):4. doi: 10.1186/2045-7022-1-4. http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/2045-7022-1-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng G, Swaidani S, Sharma M, Lauer ME, Hascall VC, Aronica MA. Hyaluronan deposition and correlation with inflammation in a murine ovalbumin model of asthma. Matrix Biol. 2011;30(2):126–134. doi: 10.1016/j.matbio.2010.12.003. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.matbio.2010.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng G, Swaidani S, Sharma M, Lauer ME, Hascall VC, Aronica MA. Correlation of hyaluronan deposition with infiltration of eosinophils and lymphocytes in a cockroach-induced murine model of asthma. Glycobiology. 2013;23(1):43–58. doi: 10.1093/glycob/cws122. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/glycob/cws122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dagenais TR, Keller NP. Pathogenesis of Aspergillus fumigatus in invasive Aspergillosis. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2009;22(3):447–465. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00055-08. http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/cmr.00055-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dardalhon V, Awasthi A, Kwon H, Galileos G, Gao W, Sobel RA, et al. IL-4 inhibits TGF-beta-induced Foxp3+ T cells and, together with TGF-beta, generates IL-9+ IL-10+ Foxp3(−) effector T cells. Nat. Immunol. 2008;9(12):1347–1355. doi: 10.1038/ni.1677. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/ni.1677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeGrendele HC, Estess P, Siegelman MH. Requirement for CD44 in activated T cell extravasation into an inflammatory site. Science. 1997;278(5338):672–675. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5338.672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dentener MA, Vernooy JH, Hendriks S, Wouters EF. Enhanced levels of hyaluronan in lungs of patients with COPD: relationship with lung function and local inflammation. Thorax. 2005;60(2):114–119. doi: 10.1136/thx.2003.020842. doi:60/2/114 [pii] 10.1136/thx.2003.020842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deudon E, Berrou E, Breton M, Picard J. Growth-related production of proteoglycans and hyaluronic acid in synchronous arterial smooth muscle cells. Int. J. Biochem. 1992;24(3):465–470. doi: 10.1016/0020-711x(92)90040-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Do Y, Nagarkatti PS, Nagarkatti M. Role of CD44 and hyaluronic acid (HA) in activation of alloreactive and antigen-specific T cells by bone marrow-derived dendritic cells. J. Immunother. (Hagerstown, MD: 1997) 2004;27(1):1–12. doi: 10.1097/00002371-200401000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donaldson DS, Apostolaki M, Bone HK, Richards CM, Williams NA. The Escherichia coli heat-labile enterotoxin B subunit protects from allergic airway disease development by inducing CD4+ regulatory T cells. Mucosal Immunol. 2013;6(3):535–546. doi: 10.1038/mi.2012.93. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/mi.2012.93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eldridge L, Moldobaeva A, Wagner EM. Increased hyaluronan fragmentation during pulmonary ischemia. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol. 2011;301(5):L782–L788. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00079.2011. http://dx.doi.org/10.1152/ajplung.00079.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Entwistle J, Hall CL, Turley EA. HA receptors: regulators of signalling to the cytoskeleton. J. Cell. Biochem. 1996;61(4):569–577. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4644(19960616)61:4<569::aid-jcb10>3.0.co;2-b. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1097-4644(19960616)61:4<569::AID-JCB10>3.0.CO;2-B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fantini MC, Becker C, Monteleone G, Pallone F, Galle PR, Neurath MF. Cutting edge: TGF-beta induces a regulatory phenotype in CD4+CD25– T cells through Foxp3 induction and down-regulation of Smad7. J. Immunol. (Baltimore, MD: 1950) 2004;172(9):5149–5153. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.9.5149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garantziotis S, Li Z, Potts EN, Lindsey JY, Stober VP, Polosukhin VV, et al. TLR4 is necessary for hyaluronan-mediated airway hyperresponsiveness after ozone inhalation. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2010;181(7):666–675. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200903-0381OC. http://dx.doi.org/10.1164/rccm.200903-0381OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Research Misconduct Found]

- Getting SJ, Mahoney DJ, Cao T, Rugg MS, Fries E, Milner CM, et al. The link module from human TSG-6 inhibits neutrophil migration in a hyaluronan- and inter-alpha-inhibitor-independent manner. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277(52):51068–51076. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M205121200. http://dx.doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M205121200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh S, Hoselton SA, Schuh JM. Characterization of CD19(+)CD23(+)B2 lymphocytes in the allergic airways of BALB/c mice in response to the inhalation of Aspergillus fumigatus conidia. Open Immunol. J. 2012a;5:46–54. doi: 10.2174/1874226201205010046. http://dx.doi.org/10.2174/1874226201205010046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh S, Hoselton SA, Schuh JM. mu-chain-deficient mice possess B-1 cells and produce IgG and IgE, but not IgA, following systemic sensitization and inhalational challenge in a fungal asthma model. J. Immunol. (Baltimore, MD: 1950) 2012b;189(3):1322–1329. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1200138. http://dx.doi.org/10.4049/jimmunol.1200138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh S, Hoselton SA, Dorsam GP, Schuh JM. Eosinophils in fungus-associated allergic pulmonary disease. Front. Pharmacol. 2013;4 doi: 10.3389/fphar.2013.00008. http://dx.doi.org/10.3389/fphar.2013.00008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh S, Hoselton SA, Asbach SV, Steffan BN, Wanjara SB, Dorsam GP, et al. B lymphocytes regulate airway granulocytic inflammation and cytokine production in a murine model of fungal allergic asthma. Cell. Mol. Immunol. 2014a doi: 10.1038/cmi.2014.103. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/cmi.2014.103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Ghosh S, Hoselton SA, Dorsam GP, Schuh JM. Hyaluronan fragments as mediators of inflammation in allergic pulmonary disease. Immunobiology. 2014b doi: 10.1016/j.imbio.2014.12.005. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.imbio.2014.12.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Ghosh S, Samarasinghe AE, Hoselton SA, Dorsam GP, Schuh JM. Hyaluronan deposition and co-localization with inflammatory cells and collagen in a murine model of fungal allergic asthma. Inflamm. Res. 2014c doi: 10.1007/s00011-014-0719-3. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00011-014-0719-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Halwani R, Al-Muhsen S, Al-Jahdali H, Hamid Q. Role of transforming growth factor-beta in airway remodeling in asthma. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 2011;44(2):127–133. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2010-0027TR. http://dx.doi.org/10.1165/rcmb.2010-0027TR. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamelmann E, Vella AT, Oshiba A, Kappler JW, Marrack P, Gelfand EW. Allergic airway sensitization induces T cell activation but not airway hyper-responsiveness in B cell-deficient mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1997;94(4):1350–1355. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.4.1350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamid QA, Minshall EM. Molecular pathology of allergic disease: I: lower airway disease. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2000;105(1 Pt 1):20–36. doi: 10.1016/s0091-6749(00)90172-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hogan C, Denning DW. Allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis and related allergic syndromes. Semin. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2011;32(6):682–692. doi: 10.1055/s-0031-1295716. http://dx.doi.org/10.1055/s-0031-1295716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoselton SA, Samarasinghe AE, Seydel JM, Schuh JM. An inhalation model of airway allergic response to inhalation of environmental Aspergillus fumigatus conidia in sensitized BALB/c mice. Med. Mycol. 2010;48(8):1056–1065. doi: 10.3109/13693786.2010.485582. http://dx.doi.org/10.3109/13693786.2010.485582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsueh RC, Roach TIA, Lin KM, O'Connell TD, Han H, Yan Z. Purification and characterization of mouse splenic B lmphocytes. AfCS Res. Rep. 2002;1(1):1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang D, Liang J, Noble PW. Hyaluronan in tissue injury and repair. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 2007;23:435–461. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.23.090506.123337. http://dx.doi.org/10.1146/annurev.cellbio.23.090506.123337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang D, Liang J, Noble PW. Hyaluronan as an immune regulator in human diseases. Physiol. Rev. 2011;91(1):221–264. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00052.2009. http://dx.doi.org/10.1152/physrev.00052.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jungsuwadee P, Benkovszky M, Dekan G, Stingl G, Epstein MM. Repeated aerosol allergen exposure suppresses inflammation in B-cell-deficient mice with established allergic asthma. Int. Arch. Allergy Immunol. 2004;133(1):40–48. doi: 10.1159/000075252. http://dx.doi.org/10.1159/000075252 [75252] [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katoh S, Ishii N, Nobumoto A, Takeshita K, Dai SY, Shinonaga R, et al. Galectin-9 inhibits CD44-hyaluronan interaction and suppresses a murine model of allergic asthma. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2007;176(1):27–35. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200608-1243OC. http://dx.doi.org/10.1164/rccm.200608-1243OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitchen JR, Cysyk RL. Synthesis and release of hyaluronic acid by Swiss 3T3 fibroblasts. Biochem. J. 1995;309(Pt 2):649–656. doi: 10.1042/bj3090649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knutsen AP, Bush RK, Demain JG, Denning DW, Dixit A, Fairs A, et al. Fungi and allergic lower respiratory tract diseases. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2012;129(2):280–291. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2011.12.970. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jaci.2011.12.970, quiz 92–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lang J, Kelly M, Freed BM, McCarter MD, Kedl RM, Torres RM, et al. Studies of lymphocyte reconstitution in a humanized mouse model reveal a requirement of T cells for human B cell maturation. J. Immunol. (Baltimore, MD: 1950) 2013;190(5):2090–2101. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1202810. http://dx.doi.org/10.4049/jimmunol.1202810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Latge JP. Aspergillus fumigatus and aspergillosis. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 1999;12(2):310–350. doi: 10.1128/cmr.12.2.310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laurent TC, Fraser JR. Hyaluronan. FASEB J. 1992;6(7):2397–2404. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lennon FE, Singleton PA. Role of hyaluronan and hyaluronan-binding proteins in lung pathobiology. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol. 2011;301(2):L137–L147. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00071.2010. http://dx.doi.org/10.1152/ajplung.00071.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lesley J, Hyman R, Kincade PW. CD44 and its interaction with extracellular matrix. Adv. Immunol. 1993;54:271–335. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2776(08)60537-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang J, Jiang D, Jung Y, Xie T, Ingram J, Church T, et al. Role of hyaluronan and hyaluronan-binding proteins in human asthma. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2011;128(2):403–11. e3. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2011.04.006. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jaci.2011.04.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maier R, Wisniewski HG, Vilcek J, Lotz M. TSG-6 expression in human articular chondrocytes. Possible implications in joint inflammation and cartilage degradation. Arthritis Rheum. 1996;39(4):552–559. doi: 10.1002/art.1780390403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makinde T, Murphy RF, Agrawal DK. The regulatory role of TGF-beta in airway remodeling in asthma. Immunol. Cell Biol. 2007;85(5):348–356. doi: 10.1038/sj.icb.7100044. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/sj.icb.7100044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manion AB. Asthma and obesity: the dose effect. Nurs. Clin. North Am. 2013;48(1):151–158. doi: 10.1016/j.cnur.2012.12.002. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cnur.2012.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kryworuchko M. Interferon-gamma inhibits CD44–hyaluronan interactions in normal human B lymphocytes. Exp. Cell Res. 1999;250:241–252. doi: 10.1006/excr.1999.4524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDermott DS, Varga SM. Quantifying antigen-specific CD4T cells during a viral infection: CD4T cell responses are larger than we think. J. Immunol. (Baltimore, MD: 1950) 2011;187(11):5568–5576. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1102104. http://dx.doi.org/10.4049/jimmunol.1102104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKee CM, Penno MB, Cowman M, Burdick MD, Strieter RM, Bao C, et al. Hyaluronan (HA) fragments induce chemokine gene expression in alveolar macrophages. The role of HA size and CD44. J. Clin. Invest. 1996;98(10):2403–2413. doi: 10.1172/JCI119054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer K, Palmer JW. The polysaccharide of the vitreous humor. J. Biol. Chem. 1934;(107):629–634. [Google Scholar]

- Murakami S, Miyake K, June CH, Kincade PW, Hodes RJ. IL-5 induces a Pgp-1 (CD44) bright B cell subpopulation that is highly enriched in proliferative and Ig secretory activity and binds to hyaluronate. J. Immunol. (Baltimore, MD: 1950) 1990;145(11):3618–3627. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murdock BJ, Shreiner AB, McDonald RA, Osterholzer JJ, White ES, Toews GB, et al. Coevolution of TH1, TH2, and TH17 responses during repeated pulmonary exposure to Aspergillus fumigatus conidia. Infect. Immun. 2011;79(1):125–135. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00508-10. http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/iai.00508-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Necas J, Bartosikova L, Brauner P, Kolar J. Hyaluronic acid (hyaluronan): a review. Vet. Med. 2008;8(53):397–411. [Google Scholar]

- Noble PW. Hyaluronan and its catabolic products in tissue injury and repair. Matrix Biol. 2002;21(1):25–29. doi: 10.1016/s0945-053x(01)00184-6. S0945053X01001846 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noble PW, Jiang D. Matrix regulation of lung injury, inflammation, and repair: the role of innate immunity. Proc. Am. Thorac. Soc. 2006;60(5):401–404. doi: 10.1513/pats.200604-097AW. http://dx.doi.org/10.1513/pats.200604-097AW. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oharazawa H, Ibaraki N, Lin LR, Reddy VN. The effects of extracellular matrix on cell attachment, proliferation and migration in a human lens epithelial cell line. Exp. Eye Res. 1999;69(6):603–610. doi: 10.1006/exer.1999.0723. http://dx.doi.org/10.1006/exer.1999.0723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohkawara Y, Tamura G, Iwasaki T, Tanaka A, Kikuchi T, Shirato K. Activation and transforming growth factor-beta production in eosinophils by hyaluronan. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 2000;23(4):444–451. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.23.4.3875. http://dx.doi.org/10.1165/ajrcmb.23.4.3875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pandey S, Hoselton SA, Schuh JM. The impact of Aspergillus fumigatus viability and sensitization to its allergens on the murine allergic asthma phenotype. BioMed Res. Int. 2013;2013:619614. doi: 10.1155/2013/619614. http://dx.doi.org/10.1155/2013/619614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papakonstantinou E, Karakiulakis G. The ‘sweet’ and ‘bitter’ involvement of glycosaminoglycans in lung diseases: pharmacotherapeutic relevance. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2009;157(7):1111–1127. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2009.00279.x. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1476-5381.2009.00279.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peck D, Isacke CM. Hyaluronan-dependent cell migration can be blocked by a CD44 cytoplasmic domain peptide containing a phosphoserine at position 325. J. Cell Sci. 1998;111(Pt 11):1595–1601. doi: 10.1242/jcs.111.11.1595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petrey AC, de la Motte CA. Hyaluronan, a crucial regulator of inflammation. Front. Immunol. 2014;5 doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2014.00101. http://dx.doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2014.00101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pilarski LM, Masellis-Smith A, Belch AR, Yang B, Savani RC, Turley EA. RHAMM, a receptor for hyaluronan-mediated motility, on normal human lymphocytes, thymocytes and malignant B cells: a mediator in B cell malignancy? Leuk. Lymphoma. 1994;14(5–6):363–374. doi: 10.3109/10428199409049691. http://dx.doi.org/10.3109/10428199409049691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pure E, Cuff CA. A crucial role for CD44 in inflammation. Trends Mol. Med. 2001;7(5):213–221. doi: 10.1016/s1471-4914(01)01963-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rafi A, Nagarkatti M, Nagarkatti PS. Hyaluronate–CD44 interactions can induce murine B-cell activation. Blood. 1997;89(8):2901–2908. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg HF, Dyer KD, Foster PS. Eosinophils: changing perspectives in health and disease. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2013;13(1):9–22. doi: 10.1038/nri3341. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nri3341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothenberg ME. CD44 – a sticky target for asthma. J. Clin. Invest. 2003;111(10):1460–1462. doi: 10.1172/JCI18392. http://dx.doi.org/10.1172/jci18392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruffell B, Johnson P. Hyaluronan induces cell death in activated T cells through CD44. J. Immunol. (Baltimore, MD: 1950) 2008;181(10):7044–7054. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.10.7044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rupprecht TA, Plate A, Adam M, Wick M, Kastenbauer S, Schmidt C, et al. The chemokine CXCL13 is a key regulator of B cell recruitment to the cerebrospinal fluid in acute Lyme neuroborreliosis. J. Neuroinflamm. 2009;6:42. doi: 10.1186/1742-2094-6-42. http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1742-2094-6-42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sahu SC. Hyaluronic acid. An indicator of pathological conditions of human lungs? Inflammation. 1980;4(1):107–112. doi: 10.1007/BF00914107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sahu S, Lynn WS. Hyaluronic acid in the pulmonary secretions of patients with asthma. Biochem. J. 1978;173(2):565–568. doi: 10.1042/bj1730565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samarasinghe AE, Hoselton SA, Schuh JM. A comparison between intratracheal and inhalation delivery of Aspergillus fumigatus conidia in the development of fungal allergic asthma in C57BL/6 mice. Fungal Biol. 2011;115(1):21–29. doi: 10.1016/j.funbio.2010.09.013. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.funbio.2010.09.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuh JM, Hoselton SA. An inhalation model of allergic fungal asthma: Aspergillus fumigatus-induced inflammation and remodeling in allergic airway disease. Methods Mol. Biol. (Clifton, NJ) 2013;1032:173–184. doi: 10.1007/978-1-62703-496-8_14. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/978-1-62703-496-8_14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shifren A, Witt C, Christie C, Castro M. Mechanisms of remodeling in asthmatic airways. J. Allergy. 2012;2012:316049. doi: 10.1155/2012/316049. http://dx.doi.org/10.1155/2012/316049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shreiner AB, Murdock BJ, Sadighi Akha AA, Falkowski NR, Christensen PJ, White ES, et al. Repeated exposure to Aspergillus fumigatus conidia results in CD4+ T cell-dependent and -independent pulmonary arterial remodeling in a mixed Th1/Th2/Th17 microenvironment that requires interleukin-4 (IL-4) and IL-10. Infect. Immun. 2012;80(1):388–397. doi: 10.1128/IAI.05530-11. http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/iai.05530-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson MA, Wilson CM, McCarthy JB. Inhibition of prostate tumor cell hyaluronan synthesis impairs subcutaneous growth and vascularization in immunocompromised mice. Am. J. Pathol. 2002;161(3):849–857. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64245-9. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64245-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singleton PA, Lennon FE. Acute lung injury regulation by hyaluronan. J. Allergy Ther. 2011;(Suppl. 4) doi: 10.4172/2155-6121.S4-003. http://dx.doi.org/10.4172/2155-6121.s4-003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Sokolowska M, Chen LY, Eberlein M, Martinez-Anton A, Liu Y, Alsaaty S, et al. Low molecular weight hyaluronan activates cytosolic phospholipase A2alpha and eicosanoid production in monocytes and macrophages. J. Biol. Chem. 2014;289(7):4470–4488. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.515106. http://dx.doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M113.515106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stern R. Devising a pathway for hyaluronan catabolism: are we there yet? Glycobiology. 2003;13(12):105R–115R. doi: 10.1093/glycob/cwg112. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/glycob/cwg112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swaidani S, Cheng G, Lauer ME, Sharma M, Mikecz K, Hascall VC, et al. TSG-6 protein is crucial for the development of pulmonary hyaluronan deposition, eosinophilia, and airway hyperresponsiveness in a murine model of asthma. J. Biol. Chem. 2013;288(1):412–422. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.389874. http://dx.doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M112.389874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamoto K, Nochi H, Tada M, Shimada S, Mori Y, Kataoka S, et al. High-molecular-weight hyaluronic acids inhibit chemotaxis and phagocytosis but not lysosomal enzyme release induced by receptor-mediated stimulations in guinea pig phagocytes. Microbiol. Immunol. 1994;38(1):73–80. doi: 10.1111/j.1348-0421.1994.tb01746.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thannickal VJ, Lee DY, White ES, Cui Z, Larios JM, Chacon R, et al. Myofibroblast differentiation by transforming growth factor-beta1 is dependent on cell adhesion and integrin signaling via focal adhesion kinase. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278(14):12384–12389. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M208544200. http://dx.doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M208544200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toole BP. Hyaluronan and its binding proteins, the hyaladherins. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 1990;2(5):839–844. doi: 10.1016/0955-0674(90)90081-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toole BP. Hyaluronan is not just a goo! J. Clin. Invest. 2000;106(3):335–336. doi: 10.1172/JCI10706. http://dx.doi.org/10.1172/jci10706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toole BP. Hyaluronan: from extracellular glue to pericellular cue. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2004;4(7):528–539. doi: 10.1038/nrc1391. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nrc1391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toshida H, Tabuchi N, Koike D, Koide M, Sugiyama K, Nakayasu K, et al. The effects of vitamin A compounds on hyaluronic acid released from cultured rabbit corneal epithelial cells and keratocytes. J. Nutr. Sci. Vitaminol. 2012;58(4):223–229. doi: 10.3177/jnsv.58.223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umetsu DT, DeKruyff RH. The regulation of allergy and asthma. Immunol. Rev. 2006;212:238–255. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2006.00413.x. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.0105-2896.2006.00413.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vachon E, Martin R, Plumb J, Kwok V, Vandivier RW, Glogauer M, et al. CD44 is a phagocytic receptor. Blood. 2006;107(10):4149–4158. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-09-3808. http://dx.doi.org/10.1182/blood-2005-09-3808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vasconcellos FC, Swiston AJ, Beppu MM, Cohen RE, Rubner MF. Bioactive polyelectrolyte multilayers: hyaluronic acid mediated B lymphocyte adhesion. Biomacromolecules. 2010;11(9):2407–2414. doi: 10.1021/bm100570r. http://dx.doi.org/10.1021/bm100570r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vignola AM, Gagliardo R, Siena A, Chiappara G, Bonsignore MR, Bousquet J, et al. Airway remodeling in the pathogenesis of asthma. Curr. Allergy Asthma Rep. 2001;1(2):108–115. doi: 10.1007/s11882-001-0077-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vistejnova L, Safrankova B, Nesporova K, Slavkovsky R, Hermannova M, Hosek P, et al. Low molecular weight hyaluronan mediated CD44 dependent induction of IL-6 and chemokines in human dermal fibroblasts potentiates innate immune response. Cytokine. 2014 doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2014.07.006. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cyto.2014.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Wardlaw AJ, Brightling C, Green R, Woltmann G, Pavord I. Eosinophils in asthma and other allergic diseases. Br. Med. Bull. 2000;56(4):985–1003. doi: 10.1258/0007142001903490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang C, Cao M, Liu H, He Y, Xu J, Du Y, et al. The high and low molecular weight forms of hyaluronan have distinct effects on CD44 clustering. J. Biol. Chem. 2012;87(51):43094–43107. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.349209. http://dx.doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M112.349209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yue BY, Baum JL, Silbert JE. Synthesis of glycosaminoglycans by cultures of normal human corneal endothelial and stromal cells. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 1978;17(6):523–527. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaman A, Cui Z, Foley JP, Zhao H, Grimm PC, Delisser HM, et al. Expression and role of the hyaluronan receptor RHAMM in inflammation after bleomycin injury. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 2005;33(5):447–454. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2004-0333OC. http://dx.doi.org/10.1165/rcmb.2004-0333OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]