Abstract

Global ischemia in humans or induced experimentally in animals causes selective and delayed neuronal death in pyramidal neurons of the hippocampal CA1. The ovarian hormone estradiol administered before or immediately after insult affords histological protection in experimental models of focal and global ischemia and ameliorates the cognitive deficits associated with ischemic cell death. However, the impact of estradiol on the functional integrity of Schaffer collateral to CA1 (Sch-CA1) pyramidal cell synapses following global ischemia is not clear. Here we show that long term estradiol treatment initiated 14 days prior to global ischemia in ovariectomized female rats acts via the IGF-1 receptor to protect the functional integrity of CA1 neurons. Global ischemia impairs basal synaptic transmission, assessed by the input/output relation at Sch-CA1 synapses, and NMDA receptor (NMDAR)-dependent long term potentiation (LTP), assessed at 3 days after surgery. Presynaptic function, assessed by fiber volley and paired pulse facilitation, is unchanged. To our knowledge, our results are the first to demonstrate that estradiol at near physiological concentrations enhances basal excitatory synaptic transmission and ameliorates deficits in LTP at synapses onto CA1 neurons in a clinically-relevant model of global ischemia. Estradiol-induced rescue of LTP requires the IGF-1 receptor, but not the classical estrogen receptors (ER)-α or β. These findings support a model whereby estradiol acts via the IGF-1 receptor to maintain the functional integrity of hippocampal CA1 synapses in the face of global ischemia.

INTRODUCTION

Transient global ischemia arising in humans as a consequence of cardiac arrest or induced experimentally in animals causes selective and delayed neuronal death and in many cases delayed onset of cognitive deficits (Liou et al, 2003; Moskowitz et al, 2010; Ofengeim et al, 2011; Etgen et al, 2011; Inagaki and Etgen, 2013). Pyramidal neurons in the hippocampal CA1 are particularly vulnerable. Histological evidence of neuronal death is not observed until 2 days after insult. During the ischemic episode, cells exhibit a transient, early rise in intracellular Ca2+, depolarize and become inexcitable. After reperfusion, cells appear morphologically normal, exhibit normal intracellular Ca2+ and regain the ability to generate action potentials for 24–72 hours after the insult (Liou et al, 2003; Moskowitz et al, 2010; Ofengeim et al, 2011). Ultimately, there is a late rise in intracellular Ca2+ and Zn2+, and death of CA1 pyramidal neurons ensues, exhibiting hallmarks of apoptosis and necrosis. The substantial delay between insult and neuronal death is consistent with the possibility of therapeutic intervention.

Estradiol, the primary estrogen produced and secreted by the ovaries, has widespread actions in the brain. Estradiol and related ovarian steroids modify the structure and function of hippocampal neurons. Estradiol enhances spine density (Hao et al, 2006; Srivastava et al, 2008; Smith et al, 2009) and synapse number (Yankova et al, 2001; Ma et al, 2010) on pyramidal cells in the hippocampal CA1. Consistent with this, estradiol enhances synaptic NMDA receptor (NMDAR) currents and enhances the magnitude of NMDAR-dependent long-term potentiation (LTP) at Schaffer collateral to CA1 (Sch-CA1) pyramidal cell synapses in the hippocampus under physiological conditions (Cordoba Montoya and Carrer, 1997; Bi et al, 2001; Gupta et al, 2001; Smith and McMahon, 2005; Smith and McMahon, 2006; Smejkalova and Woolley, 2010; Snyder et al, 2011). It is likely that these actions of estrogen facilitate the enhanced learning and memory observed in rats, primates and humans in response to estrogen replacement.

The classical estrogen receptors ERα and ERβ are expressed throughout the brain. In hippocampus, ERα and ERβ are expressed primarily on inhibitory interneurons (for review, see (Woolley, 2007; Lebesgue et al, 2009; Etgen et al, 2011; Inagaki and Etgen, 2013; Baudry et al, 2013). Estrogens produce their actions on neurons, at least in part, via binding to ERα and ERβ. Ligand activation of ERα and ERβ promotes release of heat-shock protein, estrogen receptor dimerization and formation of an activated transcription factor which recognizes Estrogen Response Elements within the promoters of target genes. In addition to its genomic actions, estrogens promote rapid nongenomic signaling events in cells by engaging intracellular pathways such as ERK/MAPK, PI3K/Akt and JAK/STAT signaling (Lebesgue et al, 2009; Micevych and Kelly, 2012). These actions may be mediated, at least in part, by GPR30, a member of the seven transmembrane superfamily of G protein-coupled receptors with high affinity for estradiol and related estrogens (for review, see (Lebesgue et al, 2009; Etgen et al, 2011; Micevych and Kelly, 2012). Activation of GPR30 by estradiol stimulates production of cAMP, mobilization of intracellular Ca2+ and activation of growth factor signaling.

Estradiol and IGF-1 act synergistically in neurons to regulate synaptic remodeling, neuronal differentiation and neuronal survival (Lebesgue et al, 2009; Garcia-Segura et al, 2010). IGF-1 receptors are critical to estradiol protection of hilar neurons from seizure-induced injury (Azcoitia et al, 1999). In the brain, estradiol and IGF-1 activate ERK/MAPK (Lebesgue et al, 2009; Etgen et al, 2011; Inagaki and Etgen, 2013), a well-characterized intracellular signaling cascade implicated in neuronal plasticity and survival (Sweatt, 2004; Thomas et al, 2005; Lebesgue et al, 2009). Upon stimulation with estradiol, ER-α and the IGF-1 receptor form a macromolecular signaling complex, which recruits and activates downstream kinases including MAPK (Kahlert et al, 2000; Mendez et al, 2003; Song et al, 2004; Jover-Mengual et al, 2007). ERK/MAPK signaling culminates in phosphorylation and activation of nuclear transcription factors such as signal transducer and activator of transcription-3 (STAT3) (Sehara et al, 2013) and cAMP-response element binding protein (CREB) (Boulware et al, 2013), which regulate expression of target genes important to neuronal survival and protection.

Whereas a single, acute injection of estradiol administered immediately prior to or after ischemia at supraphysiological levels affords protection against ischemia-induced impairment of synaptic plasticity and hippocampal-based behavior in animal models of global ischemia (Sandstrom and Rowan, 2007; Inagaki et al, 2012; Dai et al, 2013), the impact of chronic estradiol administration at near physiological concentrations is, as yet unknown. Whereas long term administration of estradiol at physiological doses prior to insult ameliorates neuronal death (Plamondon et al, 1999; Jover et al, 2002; Miller et al, 2005; Jover-Mengual et al, 2007) and cognition (Gulinello et al, 2006; De Butte-Smith et al, 2009) in global ischemia, its impact on synaptic transmission and synaptic plasticity are not well-delineated.

The present study was undertaken to examine the impact of long term estradiol pretreatment at physiological doses on the functional integrity of hippocampal CA1 pyramidal neurons in a clinically-relevant model of global ischemia. We show for the first time that estradiol acts via IGF-1 receptors to ameliorate ischemia-induced deficits in NMDAR-dependent LTP at Sch-CA1 synapses in acute hippocampal slices from animals subjected to transient global ischemia. The IGF-1 antagonist JB-1 reverses the neuroprotective effects of estradiol on both synaptic transmission and synaptic plasticity. These findings suggest that estradiol and IGF-1 act in a coordinated manner to maintain the functional integrity of CA1 neurons in the face of global ischemia.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals

Six-week old female Sprague Dawley rats weighing 100–150 g (Charles River, Wilmington, DE) at the time of ischemic insult were housed and maintained in a temperature- and light-controlled environment with a 12/12-h light/dark cycle in a facility at the Institute for Animal Studies at the Albert Einstein College of Medicine. All animal experiments were carried out in accordance with the principles and guidelines of the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. Protocols used for this study were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the Albert Einstein College of Medicine.

Ovariectomy and estradiol pellet implantation

Rats were ovariohysterectomized under isoflurane (4% induction, 2% maintenance in 70% N2O: 30% O2) anesthesia. Seven days later, pellets containing estradiol-17β (0.05 mg/pellet, 21 d sustained release; Innovative Research of America, Inc., Sarasota, FL) or placebo were inserted subcutaneously beneath the dorsal surface of the neck. Estradiol pellets were present for 14 d before ischemia and remained in place until the animals were killed at 3 d after ischemia for electrophysiology.

Global ischemia

Two weeks following pellet implantation or sham surgery, most rats were subjected to global ischemia by four-vessel occlusion as described (Miyawaki et al, 2009). Briefly, rats were deeply anesthetized under isoflurane (4% induction, 2% maintenance in 70% N2O: 30% O2) by means of a Vapomatic anesthetic vaporizer (CWE Inc., Ardmore, PA), and the vertebral arteries were irreversibly occluded by electrocoagulation to prevent collateral blood flow to the forebrain during the subsequent occlusion of the common carotid arteries. A 4-0 silk thread was also looped around the carotid arteries to facilitate subsequent occlusion. Twenty-four hours later, the animals were anesthetized again, the wound was reopened and both carotid arteries were occluded with microarterial clamps for 10 min. Arteries were visually inspected to ensure adequate reflow. During clamping, the animals were awake and spontaneously ventilating. During both surgeries, rectal temperature was monitored and maintained at 36.5–37.5 °C with a rectal thermistor and heat lamp until recovery from anesthesia. For animals subjected to global ischemia, those that failed to show complete loss of righting reflex and dilation of the pupils from 1 min after occlusion was initiated until the end of occlusion were excluded from the study. Sham operated animals were subjected to the same anesthesia and surgical procedures as animals subjected to global ischemia, except the carotid arteries were not occluded.

JB-1 intracerebroventricular (icv) administration

Isoflurane-anesthetized animals were injected with the competitive IGF-1 receptor antagonist JB-1 (10 µg; Bachem Inc., Budendorf, Switzerland) or vehicle (5 µl of 50% dimethyl sulfoxide or saline) by unilateral injection into the right lateral ventricle at a flow rate of 1 µl/min immediately after global ischemia or sham surgery. Animals were positioned in a Kopf small animal stereotaxic frame with the incisor bar lowered 3.3 ± 0.4 mm below horizontal zero. A stainless steel cannula (28 gauge) was lowered stereotaxically into the right lateral ventricle to a position defined by the following coordinates: 0.92 mm posterior to bregma, 1.2 mm lateral to bregma, 3.6 mm below the skull surface according to the atlas of Paxinos and Watson.

Electrophysiology

Hippocampal slices were prepared on day 3 following ischemia or sham surgery. Rats were anesthetized with isoflurane and sacrificed by decapitation. Whole brains were rapidly removed and placed in an ice-cold cutting solution containing/consisting of (in mM): 234 sucrose, 2.5 KCl, 1.25 NaH2PO4, 10.0 MgSO4, 1 CaCl2, 26 NaHCO3, and 20 glucose, saturated with 95% O2 and 5% CO2. After 5 min incubation in the ice-cold sucrose solution, hippocampi were removed and glued on the stage of a DTK-1000 vibrating microslicer (Dosaka-EM, Kyoto, Japan) with an agar block, and immersed in ice-cold cutting solution (50%) and normal external (50%) solution. Coronal slices (400 µm thick) were cut with a microslicer and transferred to normal external solution containing (in mM): 124 NaCl, 2.5 KCl, 2.5 CaCl2, 1.3 MgSO4, 26 NaHCO3, 1 NaH2PO4, and 10 glucose. All solutions were saturated with 95% O2 and 5% CO2 (pH 7.4). Slices were incubated for at least 1 h in the external recording solution at 32±1.5°C prior to recording.

For field recordings, slices were transferred to a submersion-type recording chamber mounted on the stage of an upright microscope (BX50WI, Olympus), held fixed by a grid of parallel nylon threads and perfused with external solution at a rate of 2 ml/min. Slices were maintained at 32 ± 1.5 °C. To record field excitatory postsynaptic potentials (fEPSPs), a patch electrode (1–2 MΩ) filled with external solution was positioned in the stratum radiatum of area CA1. fEPSPs were evoked by square pulses (10–100 mA, 200 ms) in Schaffer collateral afferents by means of a bipolar tungsten stimulating electrode (MX21XEP, Frederick Haer). Stimulations were generated with a pulse generator (Master-8) coupled through an isolator (Iso-flex; A.M.P.I.). Baseline presynaptic stimulation was delivered once every 30 s using a stimulation intensity yielding 40–60% of the maximal response (for LTP experiments). The initial slope of the fEPSP was used to measure stability of synaptic responses and to quantify the magnitude of LTP. For input/output curves, single-pulse monophasic test stimulation was applied at 0.033 Hz, and electrode positions adjusted to maximize amplitude of the fEPSP. An input/output (I/O) relationship ranging from subthreshold to maximal response was established. Fiber volley amplitude was measured from peak negative voltage to baseline. fEPSP slope was measured between 20% and 80 % of initial slope of fEPSP. Slices in which the maximal fEPSP amplitude was <1 mV were rejected. Paired-pulse facilitation (PPF) was assessed at inter-stimulus intervals ranging from 0.05 to 1 s. The PPF ratio was defined as the ratio of the amplitude of the second to that of the first fEPSP amplitude elicited by pairs of stimuli. Synaptic responses were monitored with stimuli consisting of constant current pulses of 0.1 ms duration at 0.067 Hz. LTP was induced after stable baseline recording for at least 20 min by delivery of 2 trains of stimuli (2 trains of 100 pulses at 100 Hz separated by 20 s). Field potentials were acquired using a Multiclamp700A amplifier (Axon Instruments, Union City, CA, USA) and a PCI-MIO-16E-4 data acquisition device (National Instruments, Austin, TX, USA). Stimulation and acquisition were controlled by custom acquisition software run on Igor Pro 4.09A (Wavemetrics, Inc., Lake Oswego, OR, USA).

Data analysis

To calculate the magnitude of long-term changes in synaptic strength (LTP), statistical comparisons were made between mean fEPSP slopes before and 45–60 min after tetanus. The data were analyzed online using IgorPro. Results are reported as mean ± sem. Statistical analysis was performed using two-way ANOVA followed by both Student’s paired t-test and Tukey-Kramer HSD test at the P < 0.05 significance level; these tests yielded comparable P values.

RESULTS

Estradiol enhances CA1 synaptic transmission in sham-operated animals, but does not rescue ischemia-induced deficits

Whereas chronic estradiol is known to ameliorate global ischemia-induced hippocampal injury and cognitive deficits, its impact on the functional integrity of hippocampal neurons is, as yet, unclear. To address this issue, we examined the impact of chronic estradiol (14 d prior to and 3 d after ischemia) on excitatory synaptic transmission at Sch-CA1 synapses in acute hippocampal slices from ovariectomized adult female rats subjected to sham operation or global ischemia. We focused on CA1 pyramidal neurons because these are the most vulnerable cells in animals subjected to global ischemia and are important to many forms of learning and memory.

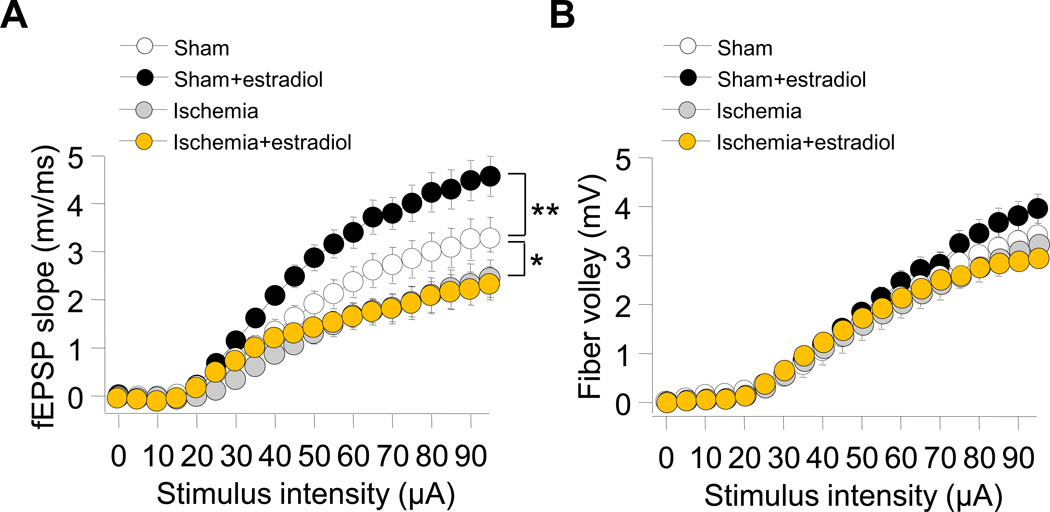

To assess the impact of ischemia on basal synaptic transmission, we stimulated Schaffer collaterals and monitored the slope input–output (I/O) relation of fEPSPs at synapses onto CA1 pyramidal neurons. Global ischemia markedly depressed the input-output relation (fEPSP slope vs. stimulus intensity) at Sch-CA1 synapses (Fig 1A). Long-term estradiol significantly enhanced the input-output relation at CA1 synapses of sham-operated rats, but did not rescue the ischemia-induced deficit in synaptic transmission (Fig 1A).

Fig. 1. Long term estradiol does not alter excitatory synaptic transmission in animals subjected to global ischemia.

Input–output (I/O) relations of excitatory synaptic transmission at Schaffer collateral to CA1 (Sch-CA1) synapses were recorded from stratum radiatum in area CA1 in acute hippocampal slices from rats subjected to sham operation at 3 days after surgery. Field excitatory postsynaptic potentials (fEPSP) slope (A) and fiber volley amplitude (B) were recorded as a function of stimulus intensity. (A) Global ischemia significantly depressed the input-output relation at Sch-CA1 synapses (Sham: 28 slices/28 rats; Ischemia: 13 slices/13 rats; Tukey-Kramer HSD, P < 0.05). Long term estradiol significantly increased the input-output relation in sham-operated rats (Sham: 28 slices/28 rats; Sham+estradiol: 30 slices/30 rats; Tukey-Kramer HSD, P < 0.05), but did not rescue the ischemia-induced decrease in fEPSP slope at Sch-CA1 synapses from ischemic rats (Ischemia: 13 slices/13 rats; Ischemia+estradiol: 16 slices/16rats; Tukey-Kramer HSD, P > 0.05). (B) Global ischemia did not detectably alter the fiber volley amplitude in placebo- treated animals. Estradiol did not detectably alter the fiber volley amplitude in animals subjected to sham surgery or global ischemia. (sham: 7 slices/7 rats; sham+estradiol: 6 slices/6 rats; Ischemia: 5 slices/5 rats; Ischemia+estradiol: 6 slices/6 rats; Tukey-Kramer HSD, P > 0.05). Here and in all figures, data represent the mean ± sem.

Chronic estradiol does not alter presynaptic function at Sch-CA1 synapses of sham or ischemic animals

To examine presynaptic function, we undertook two experimental approaches. First, we monitored the fiber volley amplitude at Sch-CA1 synapses. Fiber volley amplitude is a measure of viability of presynaptic fibers. Global ischemia did not detectably alter the fiber volley amplitude in placebo treated animals (Fig. 1B). Moreover, estradiol did not detectably alter the fiber volley amplitude in animals subjected to either sham surgery or global ischemia (Fig. 1B).

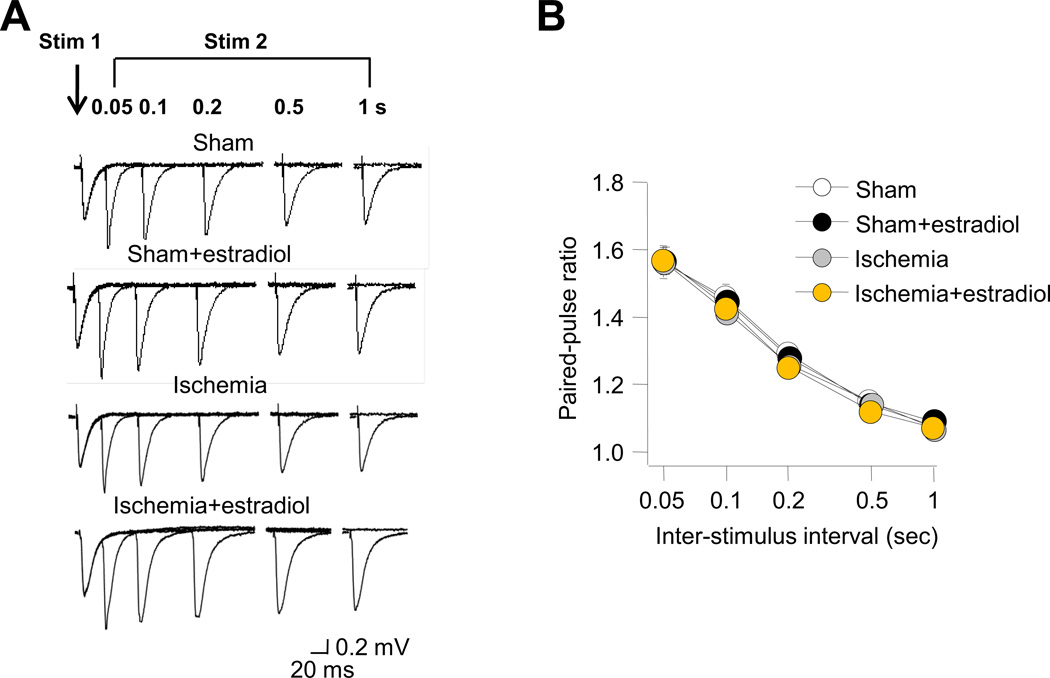

Second, we monitored the paired-pulse ratio (PPR) at Sch-CA1 synapses at five interstimulus intervals (0.05, 0.1, 0.2, 0.5 and 1 s). PPR is a form of short-term plasticity that is attributed to enhanced probability of transmitter release (Wu and Saggau, 1994; Zucker and Regehr, 2002). Estradiol did not detectably alter the PPR at Sch-CA1 synapses of animals subjected to sham operation or global ischemia (Fig. 2A,B). These results suggest that chronic estradiol, unlike acute estradiol (Smejkalova and Woolley, 2010), does not alter presynaptic release probability in sham or ischemic animals.

Fig. 2. Long term estradiol does not alter release probability in animals subjected to global ischemia.

Paired-pulse facilitation (PPF) of field excitatory postsynaptic potentials (fEPSPs) evoked by paired pulse stimulation of Schaffer collaterals at five interstimulus intervals (0.05, 0.1, 0.2, 0.5 and 1 s) were recorded from stratum radiatum in area CA1 of acute hippocampal slices from rats subjected to sham operation or global ischemia (A) at 3 days after surgery. (B) Summary data of paired pulse facilitation as a function of interstimulus interval. Estradiol did not detectably alter PPF at Sch-CA1 synapses of animals subjected to sham surgery or global ischemia (Sham: 7 slices/7 rats; Sham+estradiol: 6 slices/6 rats; Ischemia: 5 slices/5 rats; Ischemia+estradiol: 6 slices/6 rats; Tukey-Kramer HSD, P > 0.05).

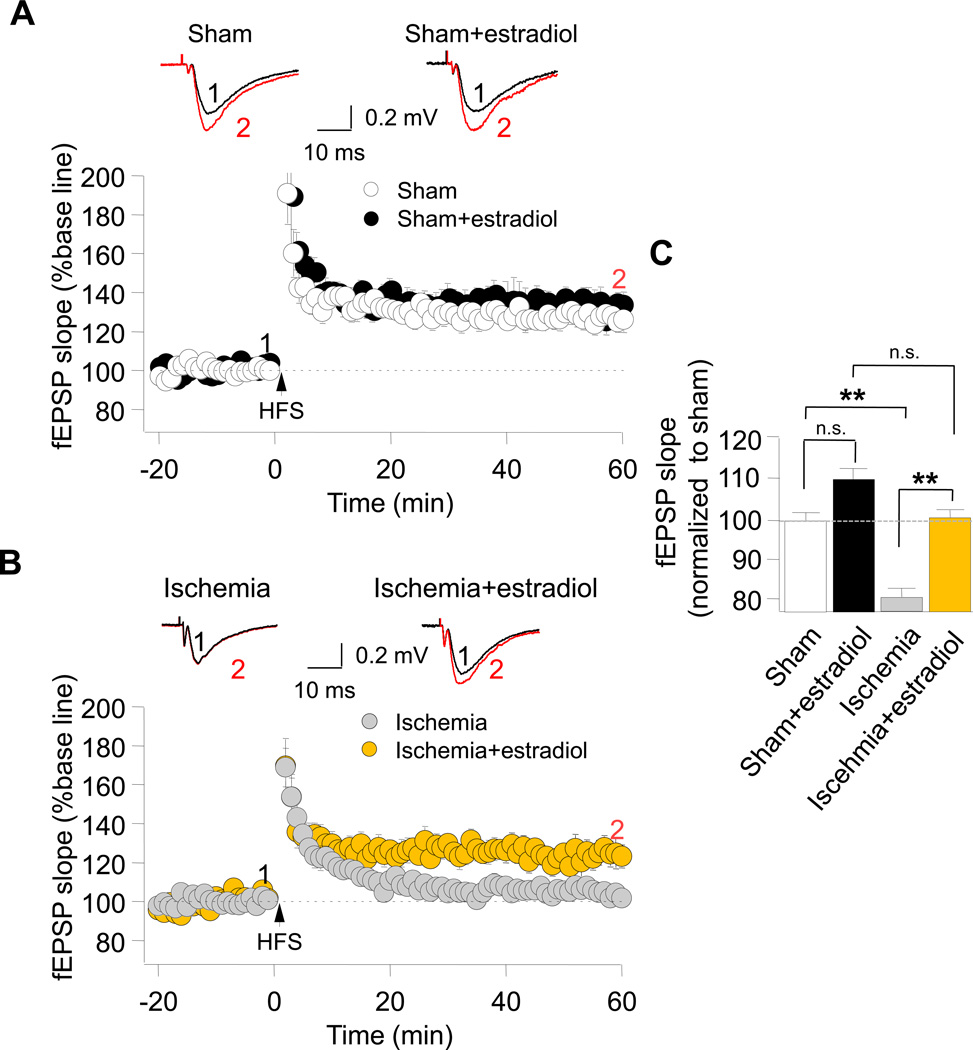

Chronic estradiol rescues synaptic plasticity at synapses onto insulted CA1 neurons

Whereas chronic estradiol is known to ameliorate ischemia-induced neuronal death and cognitive deficits, its impact on the functional integrity of hippocampal neurons, assessed by its ability to rescue synaptic plasticity is not well-delineated. To address this issue, we first examined the impact of ischemia on NMDAR-dependent, high frequency stimulation (HFS)-induced LTP at Sch-CA1 pyramidal cell synapses. Transient global ischemia impaired LTP at Sch-CA1 synapses, assessed at 3 d after reperfusion in ovariectomized female rats (Fig. 3B,C). We next examined ability of chronic estradiol to ameliorate ischemia-induced deficits in LTP at Sch-CA1 synapses. Estradiol did not significantly alter LTP in sham-operated animals (Fig. 3A,C), but rescued impaired LTP at Sch-CA1 synapses of postischemic animals (Fig. 3B,C).

Fig. 3. Long term estradiol rescues impaired LTP at Sch-CA1 synapses in rats subjected to global ischemia.

High frequency stimulation (HFS, 2 trains at 100 Hz for 1 s, separated by 20 s)-induced LTP was recorded at Sch–CA1 synapses in acute hippocampal slices from rats subjected to global ischemia or sham operation. (A) Estradiol treatment for 14 days prior to and 3 days after ischemia or sham operation did not detectably alter NMDA-dependent LTP at Sch-CA1 synapses in sham-operated rats (sham: 126.63 ± 5.78% of baseline; 11 slices/11 rats; Sham+estradiol: 131.44 ± 6.13%; 12 slices/12 rats). Here and in Fig. 4, LTP is reported as the % of baseline measured 50–60 min after HFS. (B) Global ischemia abolished LTP at Sch-CA1 synapses, assessed at 3 days after reperfusion, in ovariectomized female rats (ischemia: 104.06 ± 3.10% of baseline; 13 slices/13 rats). Long term estradiol rescued impaired LTP at Sch-CA1 synapses (Ischemia+estradiol: 123.78 ± 6.33%; 12 slices, 12 rats). (C) Summary of data in (A) and (B). Here and in Fig. 4, summary data are reported after normalization to the corresponding value for placebo-treated, sham-operated, rats.

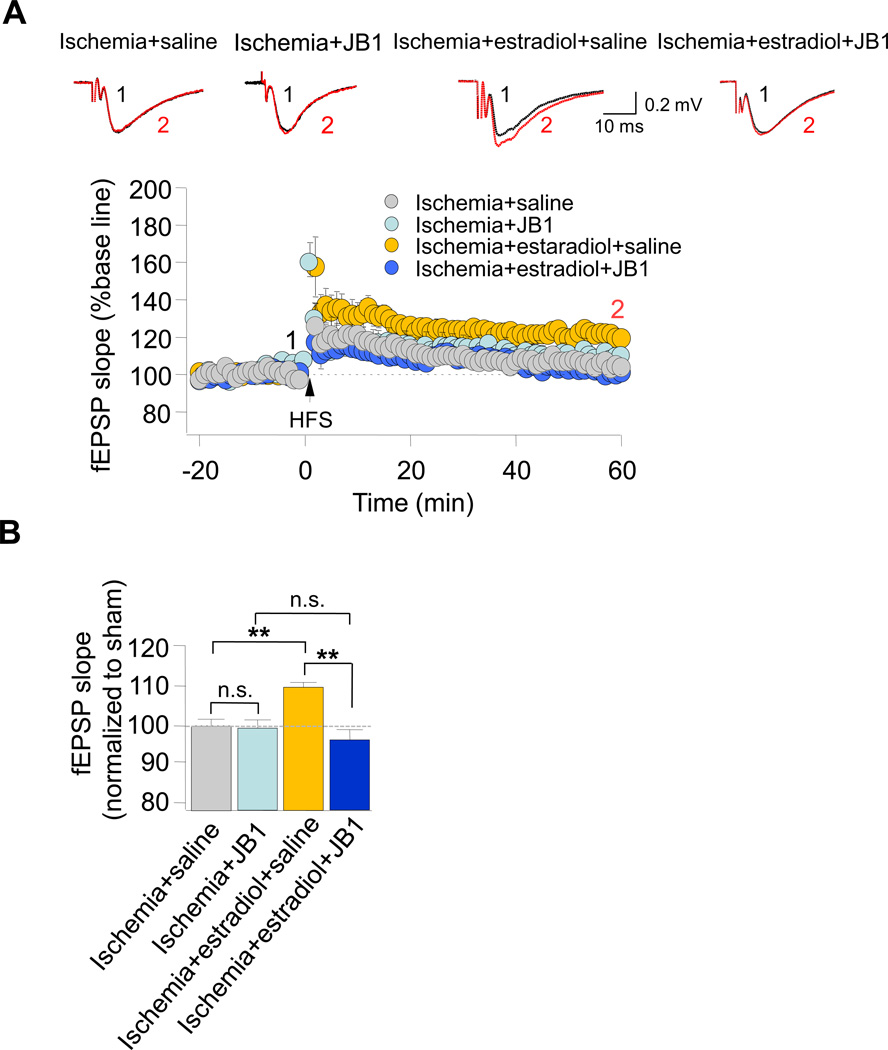

JB-1 reverses estradiol-induced rescue of LTP at synapses of insulted CA1 neurons

Estradiol is known to alter synaptic function via its actions at estrogen and/or IGF-1 receptors. JB-1 is a highly specific blocker of the IGF-1 receptor (Etgen et al, 2011). We next examined the impact of JB-1 on the estradiol-induced rescue of ischemia-induced deficits in NMDAR-dependent LTP at CA1 synapses. Long term estradiol rescued the impaired LTP observed at Sch-CA1 synapses of postischemic animals (Fig. 4A,B see also Fig. 3). A single, acute injection of the IGF-1 receptor antagonist JB-1 at 0 h after ischemia reversed the estradiol-induced rescue of LTP at Sch-CA1 synapses, assessed at 3 d after ischemia. (Fig. 4A,B). In contrast, ICI 182,780, a broad spectrum inhibitor of the classical estrogen receptors ERα and ERβ, had little or no effect on LTP in sham and ischemic animals (data not illustrated). These findings strongly suggest that chronic estradiol acts via the IGF-1 receptor to ameliorate impaired synaptic plasticity at CA1 synapses of postischemic rats and are consistent with a role for the IGF-1 receptor in estradiol neuroprotection.

Fig. 4. JB-1 reverses estradiol-induced rescue of LTP in postischemic animals.

The IGF-1 antagonist JB-1 was administered into the lateral ventricles immediately after transient global ischemia. (A) LTP was absent at Sch-CA1 synapses in acute hippocampal slices from rats implanted with placebo pellets and then subjected to global ischemia, followed by an acute injection of vehicle (gray circles); JB-1 did not detectably alter LTP recorded from placebo-implanted rats subjected to ischemia (Ischemia+JB1 (light blue circles): 105.45 ± 2.90% of baseline 12 slices/12 rats). Long term estradiol rescued impaired LTP at Sch-CA1 synapses (ischemia+estradiol (yellow circles): 123.78 ± 6.33% of baseline; 12 slices, 12 rats); JB-1 reverses estradiol-induced rescue of LTP at Sch-CA1 synapses of postischemic rats (Ischemia+estradiol+JB-1 (dark blue circles): 101.31 ± 4.03% of baseline; 12 slices/12 rats). (B) Summary data.

DISCUSSION

Global ischemia in humans or induced experimentally in animals causes selective, delayed neuronal death in pyramidal neurons of the hippocampal CA1. The ovarian hormone estradiol administered acutely or chronically affords histological protection in experimental models of ischemic stroke and ameliorates the cognitive deficits associated with ischemic cell death. However, the impact of chronic estradiol on the functional integrity of hippocampal CA1 synapses after ischemia is not clear. Here we show that long term estradiol treatment initiated 14 d prior to global ischemia and maintained on board as late as 3 days after ischemia acts via the IGF-1 receptor to protect the functional integrity of CA1 neurons in ovariectomized female rats. Global ischemia impaired basal synaptic transmission, assessed in acute slices of hippocampus by fEPSP input/output relations, and NMDAR-dependent LTP, assessed by field recording, at 3 days after surgery. Presynaptic function, assessed by PPF, was not altered. Estradiol ameliorated deficits in LTP at synapses of postischemic CA1 pyramidal neurons. Whereas the IGF-1 receptor is critical to the rescue of LTP by estradiol, ICI 182,780 did not detectably alter estradiol actions. These findings support a model whereby estradiol acts via the IGF-1 receptor, but independently of the classical estrogen receptors, to maintain the functional integrity of hippocampal CA1 synapses in the face of global ischemia and identify a novel role for the IGF-1receptor in neuroprotection of the functional integrity of CA1 pyramidal cells in a clinically-relevant model of ischemic stroke.

Findings in the present study that chronic estradiol treatment of ovariectomized female rats prior to transient global ischemia significantly improves synaptic plasticity at hippocampal synapses are consistent with previous findings from our laboratory (Gulinello et al, 2006) and others (Yang et al, 2010) that estradiol preserves cognition. Our finding that the IGF-1 receptor, but not classical estrogen receptors, is critical to estradiol-induced amelioration of LTP at synapses onto insulted CA1 neurons, differs from our earlier finding that ERα and ERβ are critical to estradiol neuroprotection, assessed histologically (Miller et al, 2005) and functionally by behavior (Gulinello et al, 2006). Findings in the present study that in sham-operated rats, estradiol enhances excitatory synaptic transmission, assessed by the input/output relation, but did not affect fiber volley amplitude or paired-pulse facilitation at CA3-CA1 synapses are consistent with findings from our lab (Inagaki et al, 2012) and others (Wu 2013) despite the differences in age and estradiol administration paradigm employed. Interestingly, whereas long term estradiol at near physiological concentrations acts primarily postsynaptic to enhance excitatory transmission and NMDAR-dependent LTP at Sch-CA1 synapses, acute estradiol applied directly to slices acts presynaptically to potentiate the probability of glutamate release (Smejkalova and Woolley, 2010). Whereas estradiol has a positive effect on excitatory synaptic transmission it is unable to rescue the ischemia depressed fEPSP.

The 4-vessel occlusion model in rats is a clinically relevant model in which a 10 min ischemic episode does not induce histologically detectable cell death until 2–3 days after ischemia yet induces virtual ablation of the CA1 pyramidal cell layer by 7 days. At 3 d, the hippocampal CA1 cell layer is mainly intact (Gorter et al, 1997). Findings in the present study that input/output relations are compromised in postischemic animals likely reflect the modest loss of CA1 pyramidal cells at 3 d after ischemia. As a consequence of the reduced number of cells, it is necessary to apply more electrical stimulation to the remaining afferent fibers to elicit the same synaptic response. Our finding that synaptic plasticity is compromised in postischemic animals is consistent with a model whereby the viability of the remaining CA1 pyramidal cells at 3 d after ischemia is compromised and thus they are less amenable to undergo an increase in synaptic efficacy. Our findings that fiber volley and PPR are unchanged at 3 d after ischemia are attributable to the conserved viability of the presynaptic fibers which emanate from pyramidal neurons in the CA3, a subfield known to survive transient global ischemia in vivo (Liou et al, 2003; Moskowitz et al, 2010; Ofengeim et al, 2011).

Our finding that chronic estradiol did not significantly alter LTP in sham-operated animals are consistent with findings of others that neither the magnitude of LTP nor excitability at Sch-CA1 synapses are affected by chronic estradiol under physiological conditions (Barraclough et al, 1999; Zhang et al, 2009). Interestingly, whereas chronic estradiol does not alter LTP in sham animals, acute estradiol administration in vivo under physiological conditions enhances synaptic NMDAR currents and the magnitude of LTP (Smith and McMahon, 2005; Smith et al, 2009). To our knowledge, the present study represents the first demonstration that chronic administration of estradiol in vivo rescues LTP at Sch-CA1 pyramidal cell synapses in a clinically-relevant model of global ischemia.

Curiously, whereas the classical estrogen receptors ERα and ERβ are critical mediators of the neuroprotective actions of estradiol in animal models of focal and global ischemia, the IGF-1 antagonist JB-1, but not ICI 182,780, a broad-spectrum blocker of the classical estrogen receptors, reversed amelioration of LTP at insulted Sch-CA1 synapses by chronic estradiol. Administration of estradiol at physiological concentrations intervenes in apoptotic death cascades and ameliorates hippocampal neuronal death in experimental models of focal and global ischemia (Etgen et al, 2011; Inagaki and Etgen, 2013). These effects occur via ERα and/or ERβ and are blocked by ICI 182,780 (Sawada et al, 2000), consistent with a role for ERα and/or ERβ. Accordingly, robust neuroprotection against ischemia-induced neuronal death is also afforded by chronic administration of the ERα-selective agonist propyl pyrazole triol (PPT) and by the ERβ-selective agonist WAY 200070-3 (Miller et al, 2005).

Estradiol and IGF-1 act synergistically in neurons to regulate synaptic remodeling, neuronal differentiation and neuronal survival (Garcia-Segura et al, 2006; Lebesgue et al, 2009). Whereas the neuroprotective effect of long-term estradiol in animal models of global and focal ischemia requires both the classical estrogen receptors and IGF-1 receptors, findings in the present study indicate that estradiol acts via the IGF-1 receptor, but independently of the classical estrogen receptors, to maintain the functional integrity of hippocampal CA1 synapses in the face of global ischemia. Emerging evidence indicates a positive correlation between the level of circulating IGF-1 and improved functional outcome in ischemic stroke, consistent with the relevance of IGF-1 receptor activity to the human situation (Bondanelli et al, 2006). Findings in the present study do not preclude a role for other estrogen receptors [in the neuroprotection afforded by estradiol] such as GPR30, a G-protein coupled receptor that binds estradiol with an affinity similar to ERα and ERβ (Thomas et al, 2005). Considerable evidence supports a role for the cellular and physiological actions of GPR30 in estradiol signaling mediated, at least in part, by a physical interaction between GPR30 and classical ERs (Prossnitz et al, 2008).

In summary, findings in this study are the first to demonstrate that chronic estradiol at near physiological conditions preserves the functional integrity of hippocampal neurons in the face of global ischemia. Global ischemia impairs basal excitatory synaptic transmission and synaptic plasticity in the form of HFS-LTP at Shaffer-collateral to CA1 synapses in young, ovariectomized female rats. Chronic estradiol rescues synaptic plasticity, but not basal synaptic transmission, assessed as late as 3 d after ischemia. We further show that estradiol acts via the IGF-1 receptor, but not the classical estrogen receptors, to preserve the synaptic integrity of Sch-CA1 synapses. This study reveals a novel and previously unappreciated role for the IGF-1 receptor in preserving the synaptic/functional integrity of CA1 neurons by chronic estradiol.

Acknowledgements

We thank Fabrizio Pontarelli for technical assistance. We thank Anne M. Etgen and the members of the Zukin laboratory for their helpful comments on the manuscript. This work was supported by NIH grants NS4569 and NS46742, a McKnight Foundation Brain Disorders Award, and a generous grant from the F.M. Kirby Foundation (to RSZ). Michael V.L. Bennett is the Sylvia and Robert S. Olnick Professor of Neuroscience and Distinguished Professor of the Albert Einstein College of Medicine. R. Suzanne Zukin is the F.M. Kirby Professor in Neural Repair and Protection.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Moskowitz MA, et al. The Science of Stroke: Mechanisms in Search of Treatments. Neuron. 2010;67:181–198. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Liou AK, et al. To die or not to die for neurons in ischemia, traumatic brain injury and epilepsy: a review on the stress-activated signaling pathways and apoptotic pathways. Prog. Neurobiol. 2003;69:103–142. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0082(03)00005-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ofengeim D, et al. Molecular and Cellular Mechanisms of Ischemia-induced Neuronal Death. In: Mohr JP, Wolf P, Grotta JC, Moskowitz MA, Mayberg M, von Kummer R, editors. Stroke: Pathophysiology, Diagnosis and Management. Philadelphia: Churchill Livingstone Elsevier; 2011. pp. 1–39. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Inagaki T, Etgen AM. Neuroprotective action of acute estrogens: animal models of brain ischemia and clinical implications. Steroids. 2013;78:597–606. doi: 10.1016/j.steroids.2012.12.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Etgen AM, et al. Neuroprotective actions of estradiol and novel estrogen analogs in ischemia: translational implications. Front Neuroendocrinol. 2011;32:336–352. doi: 10.1016/j.yfrne.2010.12.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Smith CC, et al. Estradiol and the relationship between dendritic spines, NR2B containing NMDA receptors, and the magnitude of long-term potentiation at hippocampal CA3-CA1 synapses. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2009;34(Suppl 1):S130–S142. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2009.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Srivastava DP, et al. Rapid enhancement of two-step wiring plasticity by estrogen and NMDA receptor activity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2008;105:14650–14655. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0801581105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hao J, et al. Estrogen alters spine number and morphology in prefrontal cortex of aged female rhesus monkeys. J. Neurosci. 2006;26:2571–2578. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3440-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yankova M, et al. Estrogen increases synaptic connectivity between single presynaptic inputs and multiple postsynaptic CA1 pyramidal cells: a serial electron-microscopic study. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2001;98:3525–3530. doi: 10.1073/pnas.051624598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ma XM, et al. Kalirin-7, an important component of excitatory synapses, is regulated by estradiol in hippocampal neurons. Hippocampus. 2010 doi: 10.1002/hipo.20780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cordoba Montoya DA, Carrer HF. Estrogen facilitates induction of long term potentiation in the hippocampus of awake rats. Brain Res. 1997;778:430–438. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(97)01206-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bi R, et al. Cyclic changes in estradiol regulate synaptic plasticity through the MAP kinase pathway. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2001;98:13391–13395. doi: 10.1073/pnas.241507698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gupta RR, et al. Estrogen modulates sexually dimorphic contextual fear conditioning and hippocampal long-term potentiation (LTP) in rats(1) Brain Res. 2001;888:356–365. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(00)03116-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Smith CC, McMahon LL. Estrogen-induced increase in the magnitude of long-term potentiation occurs only when the ratio of NMDA transmission to AMPA transmission is increased. J. Neurosci. 2005;25:7780–7791. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0762-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Smith CC, McMahon LL. Estradiol-induced increase in the magnitude of long-term potentiation is prevented by blocking NR2B-containing receptors. J. Neurosci. 2006;26:8517–8522. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5279-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Smejkalova T, Woolley CS. Estradiol acutely potentiates hippocampal excitatory synaptic transmission through a presynaptic mechanism. J. Neurosci. 2010;30:16137–16148. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4161-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Snyder MA, et al. Estradiol potentiation of NR2B-dependent EPSCs is not due to changes in NR2B protein expression or phosphorylation. Hippocampus. 2011;21:398–408. doi: 10.1002/hipo.20756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Baudry M, et al. Progesterone-estrogen interactions in synaptic plasticity and neuroprotection. Neuroscience. 2013;239:280–294. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2012.10.051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Woolley CS. Acute effects of estrogen on neuronal physiology. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2007;47:657–680. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.47.120505.105219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lebesgue D, et al. Estradiol rescues neurons from global ischemia-induced cell death: multiple cellular pathways of neuroprotection. Steroids. 2009;74:555–561. doi: 10.1016/j.steroids.2009.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Micevych PE, Kelly MJ. Membrane estrogen receptor regulation of hypothalamic function. Neuroendocrinology. 2012;96:103–110. doi: 10.1159/000338400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Garcia-Segura LM, et al. Interactions of estradiol and insulin-like growth factor-I signalling in the nervous system: new advances. Prog. Brain Res. 2010;181:251–272. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6123(08)81014-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Azcoitia I, et al. Gonadal hormones affect neuronal vulnerability to excitotoxin-induced degeneration. J. Neurocytol. 1999;28:699–710. doi: 10.1023/a:1007025219044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sweatt JD. Mitogen-activated protein kinases in synaptic plasticity and memory. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 2004;14:311–317. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2004.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Thomas P, et al. Identity of an estrogen membrane receptor coupled to a G protein in human breast cancer cells. Endocrinology. 2005;146:624–632. doi: 10.1210/en.2004-1064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kahlert S, et al. Estrogen receptor alpha rapidly activates the IGF-1 receptor pathway. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:18447–18453. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M910345199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mendez P, et al. Estrogen receptor alpha forms estrogen-dependent multimolecular complexes with insulin-like growth factor receptor and phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase in the adult rat brain. Brain Res Mol. Brain Res. 2003;112:170–176. doi: 10.1016/s0169-328x(03)00088-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Song RX, et al. The role of Shc and insulin-like growth factor 1 receptor in mediating the translocation of estrogen receptor alpha to the plasma membrane. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2004;101:2076–2081. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0308334100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jover-Mengual T, et al. MAPK signaling is critical to estradiol protection of CA1 neurons in global ischemia. Endocrinology. 2007;148:1131–1143. doi: 10.1210/en.2006-1137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sehara Y, et al. Survivin Is a transcriptional target of STAT3 critical to estradiol neuroprotection in global ischemia. J. Neurosci. 2013;33:12364–12374. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1852-13.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Boulware MI, et al. The memory-enhancing effects of hippocampal estrogen receptor activation involve metabotropic glutamate receptor signaling. J. Neurosci. 2013;33:15184–15194. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1716-13.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dai X, et al. Effects of estrogen on neuronal KCNQ2/3 channels expressed in PC-12 cells. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 2013;36:1583–1586. doi: 10.1248/bpb.b13-00357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sandstrom NJ, Rowan MH. Acute pretreatment with estradiol protects against CA1 cell loss and spatial learning impairments resulting from transient global ischemia. Horm. Behav. 2007;51:335–345. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2006.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Inagaki T, et al. Estradiol attenuates ischemia-induced death of hippocampal neurons and enhances synaptic transmission in aged, long-term hormone-deprived female rats. PLoS. One. 2012;7:e38018. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0038018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jover T, et al. Estrogen protects against global ischemia-induced neuronal death and prevents activation of apoptotic signaling cascades in the hippocampal CA1. J. Neurosci. 2002;22:2115–2124. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-06-02115.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Miller NR, et al. Estrogen can act via estrogen receptor alpha and beta to protect hippocampal neurons against global ischemia-induced cell death. Endocrinology. 2005;146:3070–3079. doi: 10.1210/en.2004-1515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Plamondon H, et al. Mutually protective actions of kainic acid epileptic preconditioning and sublethal global ischemia on hippocampal neuronal death: involvement of adenosine A1 receptors and K(ATP) channels. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 1999;19:1296–1308. doi: 10.1097/00004647-199912000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gulinello M, et al. Acute and chronic estradiol treatments reduce memory deficits induced by transient global ischemia in female rats. Horm. Behav. 2006;49:246–260. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2005.07.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.De Butte-Smith M, et al. Chronic estradiol treatment increases CA1 cell survival but does not improve visual or spatial recognition memory after global ischemia in middle-aged female rats. Horm. Behav. 2009;55:442–453. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2008.11.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Miyawaki T, et al. The endogenous inhibitor of Akt, CTMP, is critical to ischemia-induced neuronal death. Nat Neurosci. 2009;12:618–626. doi: 10.1038/nn.2299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wu LG, Saggau P. Presynaptic calcium is increased during normal synaptic transmission and paired-pulse facilitation, but not in long-term potentiation in area CA1 of hippocampus. J. Neurosci. 1994;14:645–654. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.14-02-00645.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zucker RS, Regehr WG. Short-term synaptic plasticity. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 2002;64:355–405. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.64.092501.114547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yang LC, et al. Extranuclear estrogen receptors mediate the neuroprotective effects of estrogen in the rat hippocampus. PLoS. One. 2010;5:e9851. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0009851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gorter JA, et al. Global ischemia induces downregulation of Glur2 mRNA and increases AMPA receptor-mediated Ca2+ influx in hippocampal CA1 neurons of gerbil. J. Neurosci. 1997;17:6179–6188. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-16-06179.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhang H, et al. Tamoxifen mediated estrogen receptor activation protects against early impairment of hippocampal neuron excitability in an oxygen/glucose deprivation brain slice ischemia model. Brain Res. 2009;1247:196–211. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2008.10.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Barraclough DJ, et al. Chronic treatment with oestradiol does not alter in vitro LTP in subfield CA1 of the female rat hippocampus. Neuropharmacology. 1999;38:65–71. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(98)00157-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sawada M, et al. Estrogen receptor antagonist ICI182,780 exacerbates ischemic injury in female mouse. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 2000;20:112–118. doi: 10.1097/00004647-200001000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Garcia-Segura LM, et al. Cross-talk between IGF-I and estradiol in the brain: focus on neuroprotection. Neuroendocrinology. 2006;84:275–279. doi: 10.1159/000097485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bondanelli M, et al. Predictive value of circulating insulin-like growth factor I levels in ischemic stroke outcome. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2006;91:3928–3934. doi: 10.1210/jc.2006-1040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Prossnitz ER, et al. Estrogen signaling through the transmembrane G protein-coupled receptor GPR30. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 2008;70:165–190. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.70.113006.100518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]