Summary

The Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) was first described in September 2012 and to date 86 deaths from a total of 206 cases of MERS-CoV infection have been reported to the WHO. Camels have been implicated as the reservoir of MERS-CoV, but the exact source and mode of transmission for most patients remain unknown. During a 3 month period, June to August 2013, there were 12 positive MERS-CoV cases reported from the Hafr Al-Batin region district in the north east region of the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. In addition to the different regional camel festivals in neighboring countries, Hafr Al-Batin has the biggest camel market in the entire Kingdom and hosts an annual camel festival. Thus, we conducted a detailed epidemiological, clinical and genomic study to ascertain common exposure and transmission patterns of all cases of MERS-CoV reported from Hafr Al-Batin. Analysis of previously reported genetic data indicated that at least two of the infected contacts could not have been directly infected from the index patient and alternate source should be considered. While camels appear as the likely source, other sources have not been ruled out. More detailed case control studies with detailed case histories, epidemiological information and genomic analysis are being conducted to delineate the missing pieces in the transmission dynamics of MERS-CoV outbreak.

Keywords: Middle East, Community, Clusters, MERS-CoV, Genome, Phylogeny, Coronavirus, Virus transmission

1. Introduction

Since the Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) was first described in September 2012,1 there have been a total of 206 cases of MERS-CoV infection with 86 deaths (41.7% mortality rate) reported to the WHO.2 All cases have had links to the Middle East and the majority of cases (156 with 63 deaths (40% mortality) have been reported from KSA as of March 15, 2014. We previously reported family3 and healthcare associated4 case clusters of MERS-CoV infections where human-to-human transmission occurred between index cases and their contacts. Whilst camels have been implicated as the reservoir of MERS-CoV,5, 6, 7 the exact source(s) and mode of transmission for most patients remain unknown. Serology consistent with a common MERS-CoV like virus in camels has been demonstrated by several studies5, 6, 7 and recently evidence has emerged of a MERS-CoV infection in a camel and in humans in contact with these camels.8, 30

During a 3 month period, May 31, 2013 to August 31, 2013, there were 12 confirmed MERS-CoV cases reported from the Hafr Al-Batin district in the north east region of the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (KSA). Hafr Al-Batin has the biggest camel market in the entire Kingdom with 500,000 camels being reared there. Hafr Al-Batin annually hosts drovers of more than 100 camel herds, comprising around 10,000 camels, from various regions of KSA, Kuwait, Qatar and the United Arab Emirates. This annual festival is known locally as “Mazayin al-Ibl, meaning “The Best of the Herds,” and attracts more than 160,000 people9 from November- December to March each year. This festival was the first to be established in the region and subsequently other camel festivals were started in neighboring countries: Qatar, Kuwait and United Arab Emirates. Since evidence is accumulating that camels are a zoonotic reservoir for MERS-CoV, we conducted a detailed epidemiological, clinical and genomic study to ascertain common exposure and transmission patterns of all cases of MERS reported from Hafr Al-Batin and relate it to other available genomic sequences from KSA and globally.

2. Methods

2.1. Selection of MERS-CoV cases

MERS-CoV cases reported from the Hafr Al-Batin region were selected for study. Epidemiological, clinical and laboratory details were collected. Clinical information included demographic data, clinical symptoms and signs, co-morbidities, contact with animals and travel history

2.2. MERS-CoV testing and genomic analyses

All suspected cases meeting the basic MERS-CoV infection criteria were confirmed in Saudi Ministry of Health regional laboratories by reverse transcription, real-time-PCR as previously described.4 MERS-CoV genomic sequences were available from a subset of the Hafr Al-Batin MERS cases.10 These viral sequences were used to test possible transmission routes for the virus and establish the plausibility of epidemiologically suspected virus transmissions using a previously described statistical test of transmission.4 Briefly, the expected number of sequence changes between two sequences was calculated as the product of the time interval between sampling, the evolutionary rate of the virus, and the maximum length of sequence shared by the two virus genomes. If the number of differences between two sequences accumulating in a given time is assumed to follow a Poisson distribution, with λ equal to the expected number of mutations, the probability of finding this number of differences between the two sequences by chance can be calculated from the cumulative density function of the Poisson distribution. A transmission pair was rejected if the number of observed mutations exceeded the 95% upper cumulative probability value. To reduce the chance of type 1 statistical errors due to multiple testing, a Bonferroni correction was applied to the significance cutoff, resulting in an adjusted significance level of 3.85 × 10–3. The rate of evolution of MERS-CoV has been estimated at 1.12 × 10–3 substitutions per site per year (95% credible interval [95% CI], 8.76 × 10–4; 1.37 × 10–3).10 To account for uncertainty in the evolutionary rate of the virus, the transmission tests were repeated at the 95% upper and lower credible intervals and checked for consistency in the results.

In addition, a plausibility test was added. A reproductive time for MERS-CoV has been estimated at 7-12 days,11 which represents the time from symptom onset in a primary case to symptom onset in a secondary case. This estimate is largely derived from hospital-based infections which may be dominated by patients with renal failure and other co-morbidities,4, 12 as well as close contact with infected cases resulting in an underestimate of the generation time. For testing the global transmission of the virus, we included an asymptomatic period when a patient might still be infectious, estimating that a case remains infectious for 14 days, and assuming that identification would occur within 7 days of infection. Thus, any two cases might be plausibly directly linked if they meet the statistical sequence test and the two sample dates differ by 21 days or less. This calculation was used to assess the likelihood that virus transmission occurred directly between two test cases and was applied to all cases infected with the Hafr-Al-Batin_1 MERS-CoV variant.

2.3. Statistical analysis

A chi-squared test was used to assess the associations of comorbidities and clinical presentations, with p values <0.05 considered significant.

3. Results

3.1. MERS-CoV cases and clusters

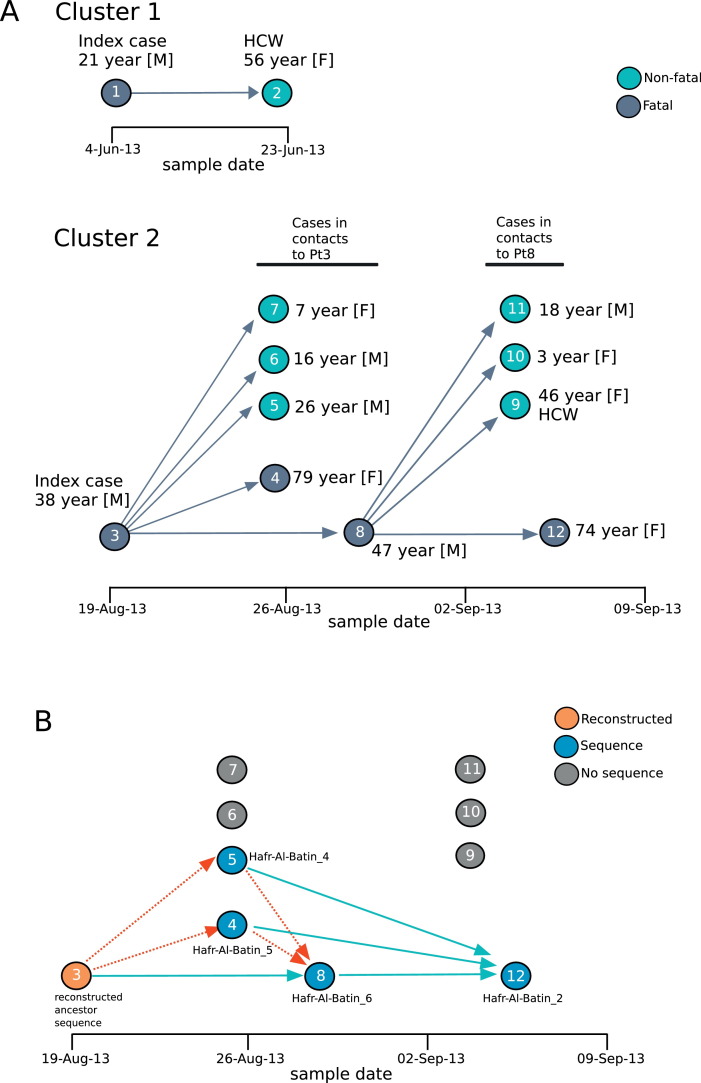

Between May 31, 2013 and August 31, 2013, there were 12 confirmed MERS-CoV cases in the Hafr Al-Batin area. Two index cases and two clusters were noted. In Cluster 1, the index case Patient 1 (as defined by first date of diagnosis) was a 21 year-old non-Saudi shepherd with onset of symptoms on May 31, 2013 and a secondary case, Patient 2, a healthcare worker contact had who had an asymptomatic infection (Figure 1 A). Cluster 2 involved a 38 year-old Saudi male, Patient 3, who owned and directly cared for camels, and had onset of symptoms on August 8, 2013. Patient 3 was closely associated with five additional MERS cases (Patients 4-8) and Patient 8, one of the secondary contacts of Patient 3, was associated with an additional four MERS cases (Patients 9-12, Figure 1A).

Figure 1.

(A) The epidemiologically defined transmission pathway of the two MERS-CoV clusters. Markers for each MERS case were placed by sample date (x-axis) and colored dark grey for fatal outcome or green for non-fatal outcome. Patient numbers are indicated within each marker. The age and gender of each case are indicated, and epidemiologically-possible contacts of Patients 1, 3 and 8 are marked by arrows. (B) Determination of genetically plausible transmission for the Hafr Al-Batin Cluster 2. Time of sample collection is indicated on the x-axis. Colored markers indicate the MERS case with the following code. Blue: MERS-CoV sequence was available for that case, grey: no sequence was available, orange: no sequence was available but the ancestral reconstructed sequence for the clade was used. Green arrows indicate statistically plausible transmission between the pair (with no direction implied), red arrows indicate that transmission between the pair is not supported statistically. Statistical tests of transmission were performed as previously described.4

3.2. Comorbidity and Clinical Presentations

Of the 12 cases, five (41.7%) had contacts with camels. The first index (June 2013) case (Patient 1) was a shepherd. In the two clusters, five patients died including the 2 index cases and 3 of their close contacts (four out of the five mortalities had comorbidities). Of those with comorbidities, all had diabetes mellitus, three had hypertension, and one was also obese and was a smoker. Comorbidities were present in four (80%) of the five symptomatic cases and in one (14%) of the seven asymptomatic cases (p = 0.07) (Table 1 ).

Table 1.

shows symptomatic and asymptomatic cases and comorbid conditions.

| Cases | Age | Gender | Comorbidity | Outcome | Animal Contact |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pt1* Index case Cluster 1 |

21 | M | none | died | yes |

| Pt2 | 56 | F | none | alive | no |

| Pt3* Index case Cluster 2 |

38 | M | DM | died | yes |

| Pt4* | 79 | F | DM, HTN | died | no |

| Pt5 | 26 | M | none | alive | yes |

| Pt6 | 16 | M | none | alive | yes |

| Pt7 | 7 | F | none | alive | no |

| Pt8* | 47 | M | Obesity, DM, HTN, smoking, HD | died | yes |

| Pt9 | 46 | F | DM, HTN | alive | no |

| Pt10 | 3 | F | none | alive | no |

| Pt11 | 18 | M | none | alive | no |

| Pt12* | 74 | F | DM, HTN | died | no |

Symptomatic case; DM=Diabetes Mellitus,HTN= hypertension, HD= Hemodialysis; M = male; F= female.

All symptomatic cases had fever, cough, shortness of breath and four (80%) complained of sore throat. Two (40%) had headache, one (20%) complained of hemoptysis and one (20%) had nausea (Table 2 ).

Table 2.

Clinical Presentations among symptomatic cases.

| Symptom | No. of cases | % |

|---|---|---|

| fever | 5 | 100 |

| sore throat | 4 | 80 |

| cough | 5 | 100 |

| shortness of breath | 5 | 100 |

| hemoptysis | 1 | 20 |

| nausea | 1 | 20 |

| headache | 2 | 40 |

3.3. Contact Investigation

The contact investigation was carried out for both family contacts and healthcare worker contacts. Among the family contacts, 7 out of 36 (19.4%) tested positive and 1 of 51 (2%) healthcare worker contacts tested positive for MERS-CoV (p = 0.0078).

3.4. Genetic tracing of MERS-CoV transmission and possible linkages

For the Hafr Al-Batin Cluster 1 we obtained a full MERS-CoV genome from the index Patient 1 (Hafr-Al-Batin_1_2013), however no useful sequence could be obtained from the only positive contact in that cluster (Patient 2, a health care worker). For Cluster 2, MERS-CoV genomic sequences were obtained from Patient 4 (Hafr-Al-Batin_5_2013), Patient 5, (Hafr-Al-Batin_4_2013), Patient 8 (Hafr-Al-Batin_6_2013) and Patient 12 (Hafr-Al-Batin_2_2013). We were unable to obtain sequence from Patient 3, however an ancestral sequence for the entire family clade was reconstructed and used as a surrogate for the Patient 3 sequence. Possible transmission routes are indicated in Figure 1B. Each patient is indicated by a filled circle placed by sample date, blue-filled circles indicate patients with sequence, grey-filled circles indicate cases with no available sequence and the orange-filled circle represents the reconstructed ancestral sequence.

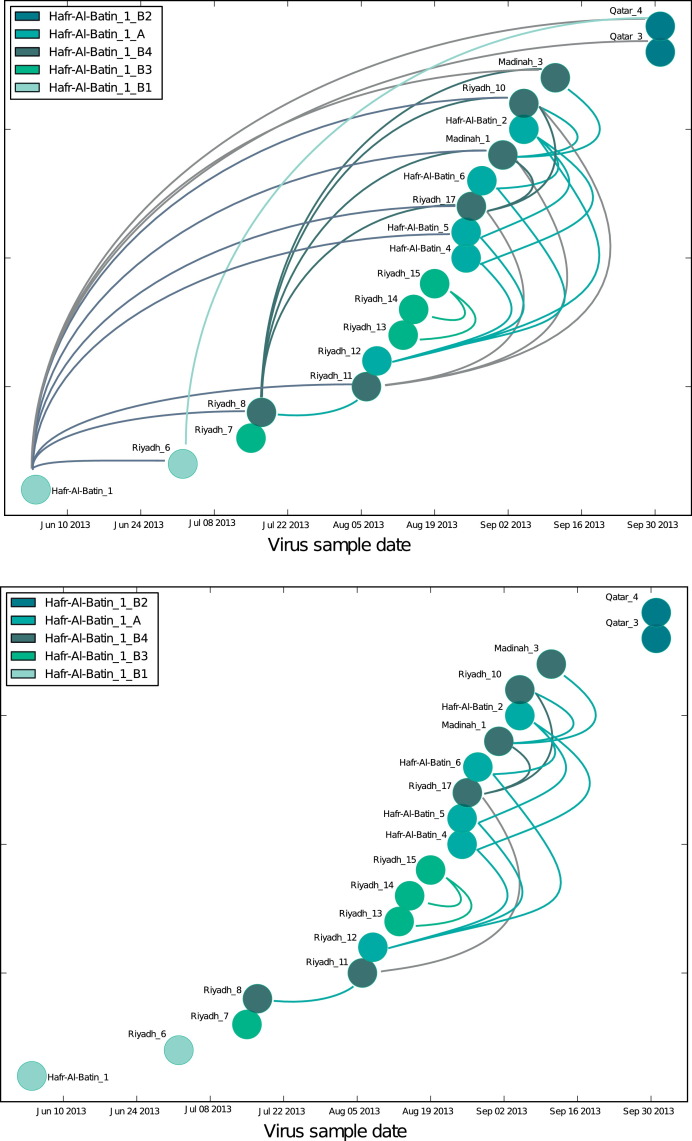

Individual cases in the second Hafr Al-Batin transmission cluster were plotted by date of the sequenced sample (Figure 2 ). Blue-filled circles indicate cases with sequence data, the orange-filled circle for Patient 3 indicates that an ancestor sequence for the clade was reconstructed and used as a surrogate, grey-filled circles indicate cases with no available sequence. Some transmissions are statistically allowed including Patient 3 to Patient 8 and Patient 4, 5 or 8 to patient 12 (green arrows). However, transmission from Patient 3 to Patient 4 or Patient 5 is not likely to have occurred (dashed red arrows); other sources of the infection should therefore be considered for Patient 4 and Patient 5.

Figure 2.

Statistically possible transmission pairs between MERS cases infected with the Hafr-Al-Batin_1 clade of MERS-CoV. All MERS cases known to be infected with the Hafr-Al-Batin_1 clade of MERS-CoV were plotted by sample date (x-axis) and color-coded by Hafr-Al-Batin_1 subclade as previously described 10. Upper panel: All statistically supported transmission pairs are marked by arcs. Lower panel: Only potential transmission pairs whose collection dates differ by 21 days or less are marked by arcs. See Methods section for additional details.

To examine MERS-CoV sources on a broader scale, the possible transmissions amongst all patients known to have been infected with the Haf Al-Batin variant were tested (Figure 2). The Hafr-Al-Batin_1 clade was first observed in Patient 1 (Hafr-Al-Batin_1) in May 201313 and since then has been identified in 19 MERS patients10 and 1 camel8 in Riyadh, Hafr Al-Batin, Madinah, and Qatar.

All MERS cases were depicted by sample date and color-coded by virus clade as previously described 10 (Figure 2, upper panel). All statistically supported transmissions are marked by arcs connecting the relevant patients. Several important patterns appear. The viruses Hafr-Al-Batin_1, Riyadh_8, Riyadh_12 are linked to a large number of possible pairs. Hafr-Al-Batin_1_2013 is an early virus in this clade and may be representative of the camel to human zoonosis that gave rise to this clade, showing linkage to 10 of the 19 cases infected with the Hafr-Al-Batin_1 clade virus. The 4 linkages from Riyadh_8, 3 linkages from Riyadh_11 and 4 linkages from Riyadh_12 viruses may provide important clues. These are viruses from patients in Riyadh with no direct links to the Hafr Al-Batin region and no contact with animals, including camels. Within a period of one month, closely-related viruses were observed in Riyadh, in the Hafr Al-Batin region as well as in Madinah, with statistical support for direct transmission events. Any MERS-CoV transmission model must account for this rapid virus movement and MERS-CoV infection with no apparent live animal contact. Furthermore, sequences from three viruses in the recently described camel/human transmission cluster in Qatar also fall within the Hafr Al-Batin cluster.8 The transmission testing supports the conclusion that the Qatar human and camel viruses are directly related to the Saudi Hafr Al-Batin cluster.

Adding the 21-day plausibility filter, (see Methods) the pattern is reduced in complexity; however important features remain (Figure 2, lower panel). The linkages between the Riyadh_12 patient and the patients in the Hafr Al-Batin family cluster (Hafr-Al-Batin_4, 5 and 6) remain. In searching for alternative sources of the infection of Patient 4 and 5, Riyadh_12 or the source of the infection of Riyadh_12 should be considered, including exposure to health care facilities, or health care workers, consumption or exposure to uncooked animal products, exposure to camels or other animals directly. A second network of transmissions passes the plausibility test with transmissions between the Riyadh_8, Riyadh_11 and Riyadh 17 cases and beyond to Madinah_1 and Madinah_3.

4. Discussion

In this report we describe the possible transmission dynamics of MERS-CoV in community case clusters from the Hafr Al-Batin region. A cluster was defined by WHO as the occurrence of > 2 patients with onset of symptoms within an incubation period of 14 days. The transmission occurs in the same setting such as a classroom, workplace, household, extended family, or hospital.14 Since the emergence of MERS-CoV, a number of clusters involving more than two people14 have been reported from France,15, 16 Italy, Jordan,17 KSA,3, 4, 18 Tunisia,19 UAE, UK20 and Qatar. The known 14 primary cases in these clusters were adult men.21 Of the involved individuals, 26% occurred in healthcare setting.21 The largest healthcare associated MERS-CoV cluster was reported from Al-Hasa, Saudi Arabia.4 In an earlier family cluster from Saudi Arabia, an adult male index case resided in an extended household of 10 other adults and 18 children. Secondary cases were identified in two sons, and a grandson.3 The findings from previous clusters showed that immunocompetent contacts exhibit mild symptoms.20, 22 In the UK cluster of MERS-CoV, two cases of MERS-CoV infection were confirmed and one of the two cases had severe illness. None of the 59 healthcare workers contacts had infection.20 In the Hafr Al-Batin cases reported here, 19.4% among the family contacts tested positive and 2% of the healthcare worker contacts were positive for MERS-CoV (p = 0.0078).

One of the differences between primary cases and secondary cases in MERS-CoV clusters is that primary cases frequently have no contact with a known MERS cases and are therefore thought to acquire infection through contact with non-human sources of the virus.23 The Hafr Al-Batin MERS Cluster 2 showed the spectrum of illness of MERS-CoV from asymptomatic to a fulminant disease as observed previously.3 In the current study, animal contact was reported in 41.7% of all cases. The presence of animal contact among asymptomatic family contacts further complicate the issue of having secondary cases as a result of direct contact or the result of exposure to the same source or host of MERS-CoV that lead to the index infection. In fact, for family cluster 2, our genetic data indicate that while Patient 8 is likely to have acquired the infection from the index Patient 3, at least two of the infected contacts (Patients 4 and 5) could not have been directly infected from Patient 3 and alternate source should be considered.

Although, there have been a number of transmissions observed within healthcare setting and interfamilial, the number of secondary transmissions seem be limited and is consistent with the R0 estimates for MERS being less than 1.11, 32 This finding is similar to previous observations from known clusters4, 24, 25 and that secondary attack rates among family members of patients in other clusters appear to be low.3, 4, 17, 25, 26 In a recent large screening study, family contacts had a higher positivity rate (3.6%) than HCW contacts (1.12%).27 Systematic implementation of infection prevention and control measures in reported clusters involving healthcare settinghas appeared to limit onward transmission to HCW and hospitalized patients.4, 15, 20, 25, 28, 29

A large annual camel fair takes place in Hafr Al-Batin each November-December to March with movement of a large number of camels both to and from Hafr Al-Batin.9 It seems that the timing of the Hafr Al-Batin sequence divergence is consistent with the annual fair and animal movement. It remains unclear if primary cases had acquired MERS-CoV from direct animal contact or as a result of contact or consumption of animal products, unpasteurized camel milk and products (ice cream). Evidence that camels are a source of human MERS-CoV infections is accumulating. Two sets of patients with camel contacts have now been analyzed and the sequence data support direct transmission between camel and human, although the sequences do not allow direction of transmission.8, 30 Serological evidence that the camel infections predate the human infection has been provided.30 Furthermore, a full MERS-CoV genome has been obtained from a camel in Egypt;31 this combined with the high prevalence of MERS-CoV seropositivity indicates that camels may be frequently infected with the virus. More detailed case control studies with detailed case histories, epidemiological information and genomic analysis are being conducted to delineate the missing pieces in the transmission dynamics of MERS-CoV outbreak.

References

- 1.Zaki A.M., van Boheemen S., Bestebroer T.M., Osterhaus A.D., Fouchier R.A. Isolation of a novel coronavirus from a man with pneumonia in Saudi Arabia. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:1814–1820. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1211721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.WHO. Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) – update.27 March 2014. http://www.whoint/csr/don/2014_03_27_mers/en/ 2014

- 3.Memish ZA, Zumla AI, Al-Hakeem RF, Al-Rabeeah AA, Stephens GM. Family cluster of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus infections. N Engl J Med. 2013 Jun 27;368(26):2487-94. http://dx.doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1303729. Epub 2013 May 29. Erratum in: N Engl J Med. 2013 Aug 8;369(6):587. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Assiri A, McGeer A, Perl TM, Price CS, Al Rabeeah AA, Cummings DA et al., KSA MERS-CoV Investigation Team. Hospital outbreak of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus. N Engl J Med. 2013 Aug 1;369(5):407-16. http://dx.doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1306742. Epub 2013 Jun 19. Erratum in: N Engl J Med. 2013 Aug 29;369(9):886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5.Reusken C.B., Haagmans B.L., Muller M.A., Gutierrez C., Godeke G.J. Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus neutralising serum antibodies in dromedary camels: a comparative serological study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2013;13:859–866. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(13)70164-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hemida MG, Perera RA, Wang P, Alhammadi MA, Siu LY, et al. Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS) coronavirus seroprevalence in domestic livestock in Saudi Arabia, 2010 to 2013. Euro Surveill 2013; 18: 20659. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Perera RA, Wang P, Gomaa MR, El-Shesheny R, Kandeil A, et al. Seroepidemiology for MERS coronavirus using microneutralisation and pseudoparticle virus neutralisation assays reveal a high prevalence of antibody in dromedary camels in Egypt, June 2013. Euro Surveill 2013;18: pii=20574. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Haagmans B.L., Al Dhahiry S.H., Reusken C.B., Raj V.S., Galiano M. Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus in dromedary camels: an outbreak investigation. Lancet Infect Dis. 2014;14:140–145. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(13)70690-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Harrigan P, Bjurström L. Heads High. Saudi Aramco World. May/June 2008, 59 (3):48-57. Available at: https://www.saudiaramcoworld.com/issue/200803/heads.high.htm.

- 10.Cotten M.W.S., Zumla A.I., Makhdoom H.Q., Palser A.L., Ong S.H., Al Rabeeah A.A. Spread, circulation, and evolution of the Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus. mBio. 2014;5 doi: 10.1128/mBio.01062-13. e01062–01013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cauchemez S, Fraser C, Van Kerkhove MD, Donnelly CA, Riley S, et al. (2013) Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus: quantification of the extent of the epidemic, surveillance biases, and transmissibility. The Lancet Infectious Diseases: doi:pii: S1473-3099(1413)70304-70309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12.Assiri A, Al-Tawfiq JA, Al-Rabeeah AA, Al-Rabiah FA, Al-Hajjar S, Al-Barrak A et al. Epidemiological, demographic, and clinical characteristics of 47 cases of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus disease from Saudi Arabia: a descriptive study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2013 Sep;13(9):752-61. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S1473-3099(13)70204-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 13.Cotten M., Watson S.J., Kellam P., Al-Rabeeah A.A., Makhdoom H.Q., Assiri A. Transmission and evolution of the Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus in Saudi Arabia: a descriptive genomic study. Lancet. 2013 Dec 14;382(9909):1993–2002. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61887-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.WHO. Interim surveillance recommendations for human infection with Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus. Available at:http://www.who.int/csr/disease/coronavirus_infections/InterimRevisedSurveillanceRecommendations_nCoVinfection_27Jun13.pdf Last accessed march 18, 2014.

- 15.Guery B., Poissy J., el Mansouf L., Sejourne C., Ettahar N. Clinical features and viral diagnosis of two cases of infection with Middle East Respiratory Syndrome coronavirus: a report of nosocomial transmission. Lancet. 2013;381:2265–2272. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60982-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mailles A., Blanckaert K., Chaud P., van der Werf S., Lina B. First cases of Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus (MERS-CoV) infections in France, investigations and implications for the prevention of human-to-human transmission, France, May 2013. Euro Surveill. 2013:18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hijawi B., Abdallat M., Sayaydeh A., Alqasrawi S., Haddadin A. Novel coronavirus infections in Jordan, April 2012: epidemiological findings from a retrospective investigation. East Mediterr Health J. 2013;19(Suppl 1):S12–S18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Omrani A.S., Matin M.A., Haddad Q., Al-Nakhli D., Memish Z.A. A family cluster of Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus infections related to a likely unrecognized asymptomatic or mild case. Int J Infect Dis. 2013;17:e668–e672. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2013.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.WHO (2013) MERS-CoV summary and literature update – as of 20 June 2013. http://wwwwhoint/csr/disease/coronavirus_infections/update_20130620/en/indexhtml. Last accessed March 18, 2014.

- 20.Health Protection Agency (HPA) UK Novel Coronavirus Investigation team. Evidence of person-to-person transmission within a family cluster of novel coronavirus infections, United Kingdom, February 2013. Euro Surveill. 2013 Mar 14;18(11):20427. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 21.Penttinen P.M., Kaasik-Aaslav K., Friaux A., Donachie A., Sudre B., Amato-GauciAJ Taking stock of the first 133 MERS coronavirus cases globally--Is the epidemic changing? Euro Surveill. 2013 Sep 26;18(39) doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.es2013.18.39.20596. pii: 20596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.ProMED-mail (2013) Novel coronavirus infection - update 22 May 2013. http://wwwpromedmailorg/directphp?id=201305221730663.

- 23.The WHOMers-Cov Research Group. State of Knowledge and Data Gaps of Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus (MERS-CoV) in Humans. PLoSCurr. 2013 Nov 12;5. pii: ecurrents.outbreaks.0bf719e352e7478f8ad85fa30127ddb8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 24.Albarrak A.M., Stephens G.M., Hewson R., Memish Z.A. Recovery from severe novel coronavirus infection. Saudi Med J. 2012;33:1265–1269. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Drosten C., Seilmaier M., CormanVM, Hartmann W., Scheible G. Clinical features and virological analysis of a case of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus infection. Lancet Infect Dis. 2013;13:745–751. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(13)70154-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pebody R.G., Chand M.A., Thomas H.L., Green H.K., Boddington N.L. The United Kingdom public health response to an imported laboratory confirmed case of a novel coronavirus in September 2012. Euro Surveill. 2012;17:20292. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Memish ZA, Al-Tawfiq JA, Makhdoom HQ, Al-Rabeeah AA, Assiri A, AlhakeemRF et al. Screening for Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus infection in hospital patients and their healthcare worker and family contacts: a prospective descriptive study. ClinMicrobiol Infect. 2014 Jan 24. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/1469-0691.12562 [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 28.Memish Z.A., Al-Tawfiq J.A., Assiri A. Hospital-associated Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus infections. N Engl J Med. 2013 Oct 31;369(18):1761–1762. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1311004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Al-Tawfiq J.A., Assiri A., Memish Z.A. Middle East respiratory syndrome novel corona MERS-CoV infection. Epidemiology and outcome update. Saudi Med J. 2013 Oct;34(10):991–994. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Memish Z.A., Cotten M., Meyer B. Human infection with MERS coronavirus after exposure to infected camels, Saudi Arabia, 2013. Emerg Infect Dis. 2014 doi: 10.3201/eid2006.140402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chu D.K.W., Poon L.L.M., Gomaa M.M. MERS Coronaviruses in Dromedary Camels, Egypt. Emerg Infect Dis. 2014;20 doi: 10.3201/eid2006.140299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Breban R., Riou J., Fontanet A. Interhuman transmissibility of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus: estimation of pandemic risk. Lancet. 2013;382:694–699. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61492-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]